11.1 Introduction

In this chapter, we compare the policy orientation of the new economic governance (NEG) prescriptions that the European Commission and Council of finance ministers (EU executives) issued to Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Romania (2009–2019) across our two cross-sectoral policy areas (employment relations and public services) and three public services sectors (transport, water, and healthcare). To what extent have they been informed by an overarching policy script that sought to commodify labour and public services? This question is crucial from this book’s labour politics perspective, as the presence of a commodifying script is a necessary (albeit not sufficient) condition for transnational countermovements that could alter the setup and policy direction of the EU’s NEG regime.

Certainly, commodifying EU interventions as such do not necessarily trigger countervailing protest movements, especially not transnational ones (Dribbusch, Reference Dribbusch2015). Successful social movements depend also on activists’ ability to construct a shared sense of injustice among people and to identify fitting targets for their grievances (Kelly, Reference Kelly2012 [1998]). Agency-oriented factors, such as activists’ framing of the problem and their interactions with workers, allies, and the public in general, are important for successful labour and social movements, including in the case of transnational collective action (Diani and Bison, Reference Diani and Bison2004; Erne, Reference Erne2008; Nunes, Reference Nunes2021; Szabó, Golden, and Erne, Reference Szabó, Golden and Erne2022). This does not, however, mean that labour activists can build transnational movements as they please.

The policy direction of the NEG prescriptions and the nature of the NEG regime shape the prospect of countervailing protests too (Erne, Reference Erne2015). Many commodifying EU laws have passed unchallenged (Kohler-Koch and Quittkat, Reference Kohler-Koch and Quittkat2013), but most transnational protests in the socioeconomic field have been triggered by commodifying EU laws (Erne and Nowak, Reference Erne and Nowak2023), for example by the Commission’s draft Services Directive or its draft Port Services Directives (Chapters 6–10). When draft EU laws favoured labour, unions usually endorsed them, for example in the case of the EU Working Time Directive in 1993 (Chapter 6). This shows that unions are primarily concerned not about the national or the EU level of policymaking but rather about its substantive outcomes and policy direction.

The key role of interest groups in policyformation processes has been acknowledged by both neo-functionalist and intergovernmentalist EU integration scholars (Haas, Reference Haas1958 [2004]; Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1993, Reference Moravcsik1998; Niemann, Lefkofridi, and Schmitter, Reference Niemann, Lefkofridi, Schmitter, Wiener, Börzel and Risse2019). Even so, EU integration scholars from both traditions have focused their attention on institutional actors (Stan and Erne, Reference Stan and Erne2023). However, whereas intergovernmentalists look at the relations between national governments, as they aggregate different societal interests into a single national interest (Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1993: 483), neo-functionalists focus on the European Commission, as it is trying to strengthen its role in the EU polity in collaboration with transnational interest groups (Niemann, Lefkofridi, and Schmitter, Reference Niemann, Lefkofridi, Schmitter, Wiener, Börzel and Risse2019). This explains the dominant focus in the EU integration literature on national or supranational institutions (Bauer and Becker, Reference Bauer and Becker2014; Bickerton, Hodson, and Puetter, Reference Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015); but, if one approaches EU integration from a labour politics perspective, the policy orientation of EU laws and NEG prescriptions is as important as the EU’s and the NEG regime’s institutional setup.

Accordingly, we have gone beyond the EU governance literature’s dominant institutional focus and analysed the – commodifying or decommodifying – policy orientation of EU governance in two cross-sectoral policy areas (employment relations and public services) and three public service sectors (transport, water, and healthcare). Concretely, in Chapters 6–10, we first outlined EU governance in these fields prior to the shift to NEG. Then, we analysed the policy orientation of EU executives’ NEG prescriptions for Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Romania (2009–2019) in their particular semantic, communicative, and policy contexts. Finally, we drew on our novel transnational European socioeconomic protest database (Erne and Nowak, Reference Erne and Nowak2023) to relate unions’ and social movements’ transnational protest actions to commodifying EU interventions since 1997 in all five empirical chapters.

This chapter summarises the findings of the preceding empirical chapters and compares the policy orientation of NEG prescriptions across time, countries, policy areas, and sectors, following the comparative research design outlined in Chapters 4 and 5. We distinguish between qualitative and quantitative prescriptions, as this distinction captures two key dimensions of commodification: the quantitative dimension of curtailment (of workers’ wages and public services’ resources) and the qualitative dimension of marketisation (of employment relations and public services). We discuss quantitative and qualitative prescriptions separately, as this allows us to compare those on employment relations with those on public services more easily.

Concretely, section 11.2 compares the commodifying and decommodifying patterns of quantitative and qualitative NEG prescriptions in our two cross-sectoral policy areas of employment relations and public services (Chapters 6–7). Section 11.3 replicates this approach and applies it to our findings for the transport, water, and healthcare sectors (Chapters 8–10). These comparisons reveal the pre-eminence of commodification in terms of the number of NEG prescriptions and their coercive power, policy rationale, and logic of deployment. Apart from a few exceptions, all qualitative NEG prescriptions across all countries and sectors pointed in a commodifying direction, tasking governments to marketise employment relations and public services. Most quantitative prescriptions of EU executives equally tasked most national governments to curtail wages and public expenditures. Over time, however, quantitative NEG prescriptions not only became less coercive but also progressively pointed in a decommodifying direction, for example, by tasking governments to invest more in public services. It is nevertheless misleading to speak of a gradual socialisation of the NEG regime (Zeitlin and Vanhercke, Reference Zeitlin and Vanhercke2018); not just because of the much weaker coercive power of decommodifying prescriptions (Jordan, Erne, and Maccarrone, Reference Jordan, Maccarrone and Erne2021; Stan and Erne, Reference Stan and Erne2023) but also given their explicit semantic links to policy rationales that are compatible with commodification (rebalance the EU economy, boost competitiveness and growth, enhance private sector involvement, expand labour market participation) and their scant links to policy rationales that may counterbalance NEG’s dominant commodifying script (enhance social inclusion, shift to green economy) (see Tables 11.2 and 11.4).

In section 11.4, we summarise the consequences for labour politics of the shift to NEG. Did the latter trigger transnational countermovements by unions and social movements, as one might expect, given the commodifying policy script that had obviously been shaping EU executives’ NEG prescriptions since 2009? Or did NEG’s country-specific methodology effectively prevent the prescriptions’ politicisation across borders – at least until March 2020 when the spread of the coronavirus across borders compelled the Commission and Council to suspend the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP)? In section 11.4, we thus assess how transnational collective actions of trade unions and social movements challenging NEG fared comparatively in the two cross-sectoral policy areas and the three public services sectors.

11.2 NEG Prescriptions on Employment Relations and Public Services

Tables 11.1 and 11.2 group the commodifying and decommodifying prescriptions received by the four countries from 2009 to 2019 under the categories operationalised in Chapter 5. In these tables, we present the quantitative and qualitative NEG prescriptions separately to facilitate the comparison of those on employment relations with those on public services.

Commodifying NEG prescriptions on employment relations and public services (cross-sectoral)

Quantitative prescriptions Quantitative prescriptions

| Employment relations | Public services | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | |||

| 2009 | ▲3 | ▲8 | 2009 | |||||||

| 2010 | ▲3 | ▲3 | ▲6 | ▲8 | 2010 | |||||

| 2011 | ▲2 | ▲2 | ▲6 | △ | ▲5 | 2011 | ||||

| 2012 | ▲ | ▲ | ▲4 | ▲ | 2012 | |||||

| 2013 | ▲ | ▲3 | ▲3 | △ | ▲5 | 2013 | ||||

| 2014 | △ | △ | 2014 | |||||||

| 2015 | △ | 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | △ | △ | 2016 | |||||||

| 2017 | △ | 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | △ | 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | △ | 2019 | ||||||||

Categories: △ = wage levels; □ = bargaining mechanisms;

⚪ = hiring & firing mechanisms.

Coercive power: ▲■⦁ = very significant; ![]()

![]() = significant; △□⚪= weak.

= significant; △□⚪= weak.

Country code: DE = Germany; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; RO = Romania.

Qualitative prescriptions Qualitative prescriptions

| Employment relations | Public services | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | |||

| 2009 | ⦁ ■2 | 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ■ | ■ | ⦁3 ■ | 2010 | ||||||

| 2011 | ■ | □ ⚪ | ■ ⦁ | ■ | ⚪ | ⦁4 ■3 ♦ | 2011 | |||

| 2012 | ■ | ■ ⦁ | ■ | ⦁2 | 2012 | |||||

| 2013 | ■ | □ ⚪ | ■ ⦁ | ⚪2 | ■ | ⚪4 □ | ⦁4 ■5 | 2013 | ||

| 2014 | ⚪ | ⚪3 □2 | 2014 | |||||||

| 2015 | □ | 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | □2 | 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ⚪ | ⚪ □ | 2017 | |||||||

| 2018 | ⚪ | 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ⚪ □ | 2019 | ||||||||

Categories: △ = resource levels; ⚪ = sector-level governance mechanisms;

□ = provider-level governance; ◊ = cost-coverage mechanisms.

Coercive power: ▲⦁■♦ = very significant; ![]()

![]()

![]() = significant; △□⚪ = weak

= significant; △□⚪ = weak

Superscript number equals number of relevant prescriptions.

Decommodifying NEG prescriptions on employment relations and public services (cross-sectoral)

Quantitative prescriptions Quantitative prescriptions

| Employment relations | Public services | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | |||

| 2009 | 2009 | |||||||||

| 2010 | 2010 | |||||||||

| 2011 | ▲i | 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | △a | △cj | 2012 | |||||||

| 2013 | △a b | △a cj | 2013 | |||||||

| 2014 | △2 bc | 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | △2 bc | 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | △2 bcj | △a ☆a | 2016 | |||||||

| 2017 | △b | △d bc | △a cg | ☆a | 2017 | |||||

| 2018 | △be | △ bc | △ad c | 2018 | ||||||

| 2019 | △be | △d bcj | ☆a | 2019 | ||||||

Categories: △ = wage levels; □ = bargaining mechanisms;

⚪ = hiring & firing mechanisms.

Coercive power: ▲ = very significant; △□⚪ = weak.

Figures in superscript = number of prescriptions.

Semantic link to policy rationale: a = Enhance social inclusion;

b = Rebalance EU economy; e = Enhance social concertation; f = Reduce labour market segmentation; i = Reduce payroll taxes.

Bold letters = semantic link to commodification script.

Qualitative prescriptions Qualitative prescriptions

| Employment relations | Public services | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | |||

| 2009 | 2009 | |||||||||

| 2010 | 2010 | |||||||||

| 2011 | 2011 | |||||||||

| 2012 | 2012 | |||||||||

| 2013 | ⚪f | 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ⚪f | 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | 2015 | |||||||||

| 2016 | ⚪f | 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ⚪f | 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | □e | 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | 2019 | |||||||||

Categories: △ = resource levels; ☆ = coverage levels.

Coercive power: ![]() = significant; △☆ = weak.

= significant; △☆ = weak.

Figures in superscript = number of prescriptions.

Semantic link to policy rationale: a = Enhance social inclusion; b = Rebalance EU economy; c = Boost competitiveness and growth; d = Shift to green economy; g = Expand labour market participation; j = Enhance private sector involvement.

Country code: DE = Germany; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; RO = Romania.

In employment relations, we distinguished a quantitative category of NEG prescriptions (wage levels) and two qualitative ones (bargaining mechanisms and hiring and firing mechanisms). In public services, we distinguished two quantitative categories: resource levels for public services provision and coverage levels, which defines the scope of public services that users can access or the population covered by public schemes. The three qualitative categories include two on the mechanisms that govern their provision (sector-level and provider-level governance mechanisms) and one on users’ access to them (cost-coverage mechanisms).

The different shades of category symbols in Tables 11.1 and 11.2 depict NEG prescriptions’ coercive power as very significant (black), significant (grey), or weak (white), as operationalised in Chapter 5. In Table 11.2, the superscript figures indicate the number of prescriptions in that category in a given year; the superscript letters signify the semantic links between the decommodifying NEG prescriptions and the policy rationales informing them. The bold superscript letters indicate semantic links to policy rationales that are compatible with NEG’s overarching commodification script; the regular letters refer to policy rationales that may run contrary to NEG’s commodification script and thus indicate potential institutional change (Crouch and Farrell, Reference Crouch and Farrell2004).

A bird’s-eye comparison based on Tables 11.1 and 11.2 reveals the dominance of commodifying NEG prescriptions in terms of their number and, most importantly, their coercive power. The tables also show that the NEG prescriptions on public services pointed more consistently than those on employment relations in commodifying policy directions across our selected countries.

The latter finding mirrors pre-NEG developments in the two areas. In employment relations, pre-NEG EU interventions by laws often pointed in a decommodifying direction (Chapter 6). By contrast, EU leaders had already promoted the commodification of public services through vertical EU interventions by law before the EU’s shift to NEG (Chapter 7). That said, the horizontal market pressures unleashed by the making and enlargement of the internal market and monetary union also commodified employment relations, albeit much more indirectly. Increased competitive horizontal market integration put pressure on unit labour costs (ULC). The Europeanisation of product markets also put pressure on national multi-employer collective bargaining systems, which had been designed to take workers’ terms and conditions out of competition (Chapter 6). As the increasing horizontal market pressures affected different locations differently, market integration led not to social and territorial convergence but to severe imbalances between core and more peripheral locations in the EU’s political economy. This explains the radical policy shift of national political and business leaders, who previously rejected EU governance interventions in collective bargaining and wages policy (Léonard et al., Reference Léonard, Erne, Marginson and Smismans2007), towards vertical NEG interventions in this field after 2008 (Chapters 2 and 3).

By contrast, decommodified public services are not subject to horizontal market pressures, except when financed through payroll taxes given their impact on ULC, as in the case of German sickness funds (Chapter 10). Decommodified public services had typically been sheltered from horizontal market pressures, but EU policymakers made public expenditure subject to the fiscal constraints set by the Maastricht Treaty’s debt and deficit criteria, as operationalised by the EU’s SGP. In addition, EU executives advanced the exposure of public services to market pressures through commodifying EU laws and court rulings. The Commission’s commodification attempts remained nevertheless incomplete because of transnational protests and the ensuing legislative amendments by the European Parliament and Council. In the 2000s, the European Parliament increasingly used its new powers as a co-legislator to curb the Commission’s enthusiasm for public service commodification (Chapter 7). The creation of the NEG regime after 2008 thus provided EU executives with a new governance mechanism to advance public service commodification, namely, one that circumvents the potential roadblocks caused by countervailing legislative amendments by the European Parliament (Chapter 3).

Tables 11.1 and 11.2 show that the patterns of commodification and decommodification in our two cross-sectoral policy areas differed across countries and over time. Moreover, commodification advanced through different channels, with implications for the countervailing actions of unions and social movements. We thus assess the prescriptions in these areas in more detail, starting with those that target the quantitative aspects of employment relations and public services. After that, we compare the prescriptions that intervene qualitatively in these areas.

Curtailing Wages and Public Expenditure

Cutback measures first targeted Ireland and Romania, two countries that were subject to bailout conditionality. Their governments signed Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) with EU institutions and the IMF, which set out in detail the conditions that these governments needed to fulfil to receive financial assistance to prevent them from defaulting on their sovereign debt.

As Table 11.1 shows, the Irish and Romanian governments received very coercive commodifying prescriptions on both wages and public service resource levels every year between 2009 and 2013 (Romania) and from 2010 to 2013 (Ireland). The superscript numbers in the table indicate that the Irish and Romanian governments received more than one such prescription per year. The dark black shade of the symbols for Ireland and Romania demonstrates that the coercive power of these prescriptions was very significant in that period. If they had not stuck to their commitments to cut wages and public spending, the countries would have risked not getting the next tranche of their bailout package, directly threatening them with default. Prescriptions in both cross-sectoral areas followed the same underlying logic of using curtailment as a tool not only to restore budget balance but also to promote international competitiveness. Linking wage and public service resource cuts, calls for wage reductions for workers in the public sector featured prominently in both countries. Prescriptions set detailed targets on how much governments should save on public sector workers’ wages and specified measures on how to achieve these savings.

Table 11.1 also shows that NEG prescriptions to cut wages and public service resources extended beyond the period of immediate crisis management and beyond the countries under direct bailout conditionality. Whereas EU bailout programmes targeted wages and public service resources in an ad hoc manner, after 2011 the European Semester process provided a systematic framework for the EU governance of wages and public service resources (Chapter 2).

First, the Six-Pack of EU laws strengthened the coercive power of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP) of the EU’s SGP. Second, the Six-Pack’s new Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP) subjected national wage policy for the first time to a coercive EU surveillance and sanctioning regime by including a ceiling for ULC increases on the MIP scoreboard (Chapter 2). After 2012, EU executives could thus issue ULC-related NEG prescriptions to curtail wage growth. As the MIP’s ULC indicator did not include a floor, EU executives could not issue ULC-related prescriptions in favour of higher wages (Chapter 2), although the excessively low wage increases in surplus countries like Germany during the 2000s caused excessive macroeconomic imbalances within the EU (Erne, Reference Erne2008). Given the biased setup of the MIP’s ULC indicator, it is hardly surprising that deficit countries like Ireland depressed wages more than required under the MIP scoreboard’s nominal ULC-increase ceiling (Jordan, Erne, and Maccarrone, Reference Jordan, Maccarrone and Erne2021: 202). In designing the NEG regime, EU policymakers thus not only strengthened the pressures to curtail public spending through the revised EDP but also opened the possibility to curtail wages through the new MIP, which set a ceiling but no floor for nominal ULC increases (see Chapter 6).

Table 11.1 reveals the continuation of commodifying prescriptions in wages and public service resources for Ireland until 2016 (three years after Ireland exited its bailout programme) and for Romania until 2019. From 2011 to 2014, Italian governments also received a string of prescriptions to cut public service resources, although Italy was running primary budget surpluses in these years. Conversely, Germany received one prescription on the curtailment of public service resources and none on the curtailment of wages. After 2016, only Romania continued to receive commodifying prescriptions on wages levels, whereas the other countries received prescriptions to increase wages (Germany) and public service resource levels (Germany, Ireland, and Italy).

Boosting Wages and Public Investment

To repeat, the revised EDP and the inclusion of a nominal ULC indicator in the MIP scoreboard gave EU executives powerful tools to pursue commodification through cutting back wages and public service resources. Conversely, the MIP included a current account imbalances indicator, thereby opening the way for decommodifying prescriptions in both areas. In the case of current accounts, EU executives singled out not only deficits but also surpluses as a potential source of EU-wide macroeconomic imbalances. The coercive power of their expansionary NEG prescriptions for surplus countries was weak, as the European Commission never attempted to open an MIP against a surplus country that pursued overly restrictive wage and fiscal policies.

From 2012 onwards, EU executives nevertheless started looking at wages and public spending through the lens of current account surpluses also. Table 11.2 shows that Germany was the first to get decommodifying prescriptions to increase wages and fiscal resources for public services. The Commission interpreted the tightness of the German labour market and wage moderation not only as a success of earlier commodifying reforms but also as a source of EU-wide macroeconomic imbalances (Commission, Country Reports Germany SEC (2011) 714: 2, SWD (2012) 305: 19). Consequently, from 2013 onwards, Germany received a string of expansionary NEG prescriptions to increase wages that were semantically linked to the policy rationale to ‘rebalance the EU economy’, as outlined in Table 11.2. After the Commission identified Germany as a state causing macroeconomic imbalances, albeit not excessive ones, its government also started receiving a string of weak NEG prescriptions that asked it to use its available fiscal space to increase public investment.

Subsequently, EU executives issued resource-related decommodifying prescriptions to Ireland, Italy, and Romania too. Whereas Romania received its first expansionary prescriptions on public services in 2016, the prescriptions on public service resources issued to Ireland changed their policy direction in 2017. In 2019, Italy also received a decommodifying prescription on public service resources. As opposed to Germany, none of these three countries received any prescriptions calling for higher wages to ‘rebalance the EU economy’. The expansionary prescriptions for Ireland, Italy, and Romania were semantically linked to other policy rationales that were typically subordinated to, rather than challenging NEG’s commodifying logic (Table 11.2). Whereas the prescriptions for Romania on greater public investments were meant to ‘enhance of social inclusion’, which is a decommodifying rationale, those for Italy and Ireland were meant to ‘boost competitiveness and growth’ and to ‘enhance private sector involvement’ in the provision of public services; these are rationales that support rather than challenge NEG’s commodification script. The latter two rationales also featured in the German case, and the Italian and Irish prescriptions with explicit semantic links to the ‘boost competitiveness and growth’ rationale were implicitly also related to the ‘rebalance the EU economy’ rationale. After all, greater German demand (boosted by more expansionary German wage and fiscal policies) must be complemented by a concomitant upgrading of the productive apparatus in the EU’s periphery to achieve the stated goal of a more balanced EU economy (Chapter 2; Aglietta, Reference Aglietta2019).

To summarise, the curtailment of wages and public service resources was the dominant theme of NEG prescriptions in our two cross-sectoral policy areas until 2016. In decreasing numbers and with weakening coercive power, they kept appearing until 2019. Over time however, we see a shift towards more expansionary NEG prescriptions on both wage and public service resource levels. This seems to lend support to those who identified a shift to a more social Semester process after the inauguration of Jean-Claude Juncker as president of the Commission in 2014 (Chapter 4). If, however, we take into account the unequal coercive power of these decommodifying prescriptions and their semantic links to their underlying policy rationales, we can see how such prescriptions can still be compatible with NEG’s overarching commodification logic.

In all cases, the coercive power of decommodifying prescriptions was weak, by contrast to commodifying ones. Most expansionary prescriptions on wages or resources for public services were linked to rationales that were subordinated to NEG’s overarching commodifying script. Their decommodifying orientation represents a side-effect rather than an indicator of a countervailing policy script. Neither the wage increases nor the public investment recommendations for Germany were about social concerns but about rebalancing the EU economy, that is, boosting internal demand in Germany to create greater export opportunities for firms from other EU countries. Likewise, NEG prescriptions on greater public investment were frequently linked to calls for greater private-sector involvement in the provision of public services. When governments were tasked to spend more money on public services, this expenditure was typically not meant for (in-house) public services providers and public services workers. Rather, the EU executives’ NEG prescriptions incentivised the funnelling of public funds towards private actors through marketising arrangements. This picture becomes very clear when we analyse the policy orientation of the qualitative NEG prescriptions in our two cross-sectoral areas, which we do next.

Marketising Employment Relations and Public Services

Tables 11.1 and 11.2 reveal a much more consistent commodification pattern among the qualitative NEG prescriptions in our two cross-sectoral policy areas compared with the quantitative ones discussed in the previous section. All qualitative NEG prescriptions on public services across all four countries point in a commodifying direction. National differences matter only in terms of the prescriptions’ coercive power, given the different locations of our four countries in the EU’s NEG enforcement regime. In the area of employment relations, all countries except Germany received very constraining (Ireland, Romania) and constraining (Italy) NEG prescriptions that tasked governments to commodify their collective bargaining systems and workers’ hiring and firing mechanisms through reforms of their labour laws (Ireland, Italy, Romania). Germany by contrast did not receive any qualitative prescription that pointed in a commodifying direction, as EU executives were satisfied with the labour market reforms that the Schröder government (1998–2005) had already introduced to increase national competitiveness before the EU’s shift to the NEG regime. Accordingly, EU executives stopped issuing additional commodifying NEG prescriptions on collective bargaining and hiring and firing mechanisms once the receiving governments had implemented them, as happened in case of Italy with the Jobs Act adopted by the Renzi government in 2015.

By contrast, public services were targeted in a much more sustained manner by qualitative commodifying prescriptions. The commodifying NEG prescriptions on how to govern public service providers and users’ access to these services were not only far-reaching across all countries but also spanned the entire NEG period from 2009 to 2019, as Table 11.1 demonstrates. These prescriptions concerned the operational modes of public services and ownership structures. EU executives prescribed, inter alia, corporate governance reform of state-owned enterprises, performance-related pay in public administration, and the corporatisation of (local) public service providers. NEG prescriptions for Romania and Italy explicitly tasked their governments to privatise public services too. These prescriptions show that the NEG’s drive to commodify public services went further than any previous attempts at commodification through the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure. EU executives put indirect pressures on governments to balance budgets by selling off public assets in the run-up to economic and monetary union (EMU), but privatisation officially constituted a taboo during the pre-NEG history of EU integration, as its ‘Treaties shall in no way prejudice the rules in Member States governing the system of property ownership’ (Art. 345 TFEU). Even so, EU executives issued NEG prescriptions with very significant and significant coercive power to both Romania and Italy, forcing them to implement privatisation plans.

It is also important to compare the trajectories of quantitative and qualitative commodifying NEG prescriptions. Whereas the prescriptions on curtailing and marketising measures went hand in hand in the first years of the NEG regime, the focus of NEG prescriptions gradually moved away from curtailment towards marketisation, mirroring the Commission’s increased flexibility concerning the EU’s deficit and debt targets in exchange for more ambitious structural reforms. The corresponding shift in the centre of gravity of NEG prescriptions from curtailment towards marketisation, however, hardly represented a softening – or socialisation – of NEG, as acknowledged by Mario Monti, the former Italian prime minister and EU Commissioner:

The task of government is harder when reforms directly affect the interests of well-organised groups, businesses, professionals or public service employees …. That is why I welcome the recent reorientation of EU policy – not away from fiscal policy but towards emphasis on country-specific recommendations on structural reforms.

Accordingly, all NEG prescriptions across all four countries and all years tasked governments to marketise public services, despite the presence of decommodifying NEG prescriptions on resources for public services after 2013. In turn, NEG prescriptions tasked all governments except Germany’s to implement marketising reforms in employment relations, as the Schröder government had already implemented far-reaching reforms before 2008 (Chapter 6).

By contrast, and as Table 11.2 shows, decommodifying qualitative prescriptions were almost entirely absent, except in a very few employment relations cases. Although EU executives welcomed the Hartz labour market reforms in Germany in the 2000s, they acknowledged that they went too far in one aspect, as the flourishing of tax-exempt mini-jobs would draw young and old workers away from seeking full-time employment. To reduce the segmentation of the German labour market, they asked the German government from 2013 onwards to facilitate the transition from mini-jobs to standard employment. In 2018, EU executives implicitly accepted that the dismantling of multi-employer collective bargaining in Romania also went too far and issued a (weak) prescription that asked its government to enhance social dialogue.

An Overarching Commodification Script across the Two Cross-sectoral Policy Areas?

Our analysis shows that NEG prescriptions across the two cross-sectoral policy areas were largely informed by an overarching commodification script, especially in the case of the prescriptions belonging to our qualitative analytical categories.

Much of the debate on the EU’s NEG regime has so far typically focused on austerity – in other words, on the curtailment of wages and public resources (Blyth, Reference Blyth2013). As outlined in Chapter 4, the relevant discussion has revolved around the question of whether or not successive rounds of NEG prescriptions turned away from austerity. Our study has revealed that austerity is neither the only channel of commodification of employment relations and public services nor the most prominent one. Our analysis has revealed that the NEG prescriptions across the two cross-sectoral policy areas are informed by an overarching commodification script. However, the connective glue that holds NEG prescriptions together over time and across countries is not the push to curtail spending through austerity measures but rather the pressure to commodify public services and employment relations through marketising structural reforms. In this sense, it would be wrong to construct a dichotomy between fiscal retrenchment before 2014 and the expansion of public investment after that.

By comparing the NEG prescriptions in the two cross-sectoral policy areas, our study also revealed that NEG’s commodifying prescriptions targeted the governance of public services across all four countries, whereas the same did not happen in employment relations. In this area, Germany received one commodifying NEG prescription and several decommodifying ones. We must look beyond NEG to find the reasons for this. To explain these differences, we put the NEG regime in each cross-sectoral area and the three sectors into the historical perspective of EU integration in these fields (Chapters 6–10).

In employment relations, increased horizontal pressures triggered by the creation of the European internal market and monetary union were the main drivers of commodification before NEG. By contrast, horizontal market pressures played a much more limited role in public services. Correspondingly, the majority of EU law-making through the ordinary legislative procedure in employment relations served the purpose of correcting the commodifying effects of horizontal market integration by establishing minimum standards for workers across the EU. Each milestone of EU market and monetary integration was accompanied by decommodifying laws that established a plinth of EU labour standards across all member states in the areas of labour mobility, social policy coordination, occupational health and safety, and working conditions. These measures, however, were unable to counterbalance the market pressures unleashed by EU economic and monetary integration. Consequently, the EMU legitimised wage moderation and commodifying reforms of employment relations in many EU economies in the 2000s, most notably in Germany, which reported the highest ULC of all our four countries. German production sites faced particularly strong competitive pressures in the much more integrated European and global economy as a result of the growth of new transnational supply chains in the former Eastern bloc. In turn, the Schröder government, employers, and industrial relations scholars used the increased horizontal market pressures to legitimise wage moderation and the commodifying Hartz welfare and labour market reforms in the early 2000s, which subsequently also informed EU executives’ NEG prescriptions elsewhere (Chapter 6).

In public services, commodification through horizontal market integration advanced slowly. The main channel of commodification in this policy area had been vertical interventions by commodifying EU laws on public services and the debt and deficit benchmarks set by the Maastricht Treaty and the SGP. Following on from a series of sectoral liberalisation directives and court rulings, in 2004 Commissioner Bolkestein presented a draft Services Directive that aimed to deregulate services across all sectors in one go, including the laws governing the transnational posting of service workers. However, unprecedented transnational social-movement and union protests and the legislative amendments by the EU’s legislators curbed Bolkestein’s ambitions. Conversely however, the anti-Bolkestein protest movement was unable to turn the energy of its mobilisations into a sufficiently strong movement for a decommodifying EU Directive on Services of General Interest. This enabled EU executives to pursue their commodifying public service agenda further, through new sectoral service liberalisation directives as well as corresponding NEG prescriptions (Chapters 7–10).

In sum, EU executives’ NEG prescriptions on public services and employment relations generally pointed in a commodifying policy direction but not to the same degree across all categories, countries, and years. These variegated patterns of NEG prescriptions do not reflect their drafters’ conflicting – commodifying or decommodifying – policy objectives but rather the unequal progress of commodification across countries and policy areas. At times, EU executives also issued decommodifying prescriptions, but their coercive power was much weaker. In addition, decommodifying prescriptions were usually linked to policy rationales that were compatible with the overarching logic of commodification. We revealed a strong overarching commodifying logic in NEG prescriptions in qualitative public services categories (sector-level governance mechanisms, provider-level governance mechanisms, cost-coverage mechanisms). In these categories, all prescriptions across all four countries and all eleven years clearly pointed in a commodifying direction, even though their coercive power differed depending on the countries’ location in the NEG policy enforcement regime at a given time (Tables 11.1 and 11.2). Can we say the same about the NEG prescriptions for the three specific public services sectors: transport, water, and healthcare services?

11.3 Comparing NEG Prescriptions on Transport, Water, and Healthcare Services

By comparing NEG prescriptions for Germany, Ireland, Italy, and Romania (2009–2019) across the public transport, water, and healthcare services sectors, we pursue two objectives. First, we map the patterns of their commodifying or decommodifying policy orientation (Chapters 4, 8–10). Second, we assess the extent to which prescriptions across the sectors mirror an overarching commodification script. We do that because the manifestation of a pan-European commodification script informing NEG’s country-specific policy prescriptions is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for the emergence of countervailing transnational movements.

Tables 11.3 and 11.4 reveal the dominance of commodifying NEG prescriptions across all three sectors and four countries, especially in our qualitative categories. NEG’s focus on qualitative policy reforms is crucial, as reforms are more difficult to reverse than the quantitative curtailment of resources for the provision of public services.

Commodifying NEG prescriptions on public services (sectoral)

| Quantitative prescriptions | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport | Water | Healthcare | |||||||||||

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | ||

| 2009 | 2009 | ||||||||||||

| 2010 | ▲ | 2010 | |||||||||||

| 2011 | ▲ | ▲ | 2011 | ||||||||||

| 2012 | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | 2012 | |||||||||

| 2013 | △ | ▲ | ▲3 ★ | 2013 | |||||||||

| 2014 | 2014 | ||||||||||||

| 2015 | 2015 | ||||||||||||

| 2016 | △ | 2016 | |||||||||||

| 2017 | △ | 2017 | |||||||||||

| 2018 | △ | 2018 | |||||||||||

| 2019 | △ | 2019 | |||||||||||

| Qualitative prescriptions | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport | Water | Healthcare | |||||||||||

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | ||

| 2009 | ⦁4 | 2009 | |||||||||||

| 2010 | ⦁2 ■ | ♦ | ⦁ | ♦ | 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ⚪2 | ⦁18 ■4 | ■ ♦ | ⚪ | ⦁ | ⦁ ■ ♦ | 2011 | ||||||

| 2012 | ⚪ | ⦁12 ■2 | ■ ♦ | ⚪ | ⦁ ■ ♦ | 2012 | |||||||

| 2013 | ⚪ | ⚪3 | ⦁6 ■5 | ⚪ | ■ ♦ | ⚪ | ⚪ | ⦁ ■2 | ⦁2 ■3 ♦ | 2013 | |||

| 2014 | ⚪ | ⚪ □ | ⚪ | ⚪ | ⚪2 | 2014 | |||||||

| 2015 | ⚪ | □ | 2015 | ||||||||||

| 2016 | ⚪ □ | ⚪ | 2016 | ||||||||||

| 2017 | ⚪ | 2017 | |||||||||||

| 2018 | ⚪ | 2018 | |||||||||||

| 2019 | □ | | ⚪ | ⚪ | 2019 | ||||||||

Categories: △ = resource levels; ☆ = coverage levels; ⚪ = sector-level governance mechanisms; □ = provider-level governance mechanisms; ◊ = cost-coverage mechanisms.

Coercive power: ▲★■⦁♦ = very significant; ![]()

![]() = significant; △□⚪◊ = weak.

= significant; △□⚪◊ = weak.

Superscript number equals number of relevant prescriptions. Country code: DE = Germany; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; RO = Romania.

Decommodifying NEG prescriptions on public services (sectoral)

| Quantitative prescriptions | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport | Water | Healthcare | |||||||||||

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | ||

| 2009 | 2009 | ||||||||||||

| 2010 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

| 2011 | 2011 | ||||||||||||

| 2012 | 2012 | ||||||||||||

| 2013 | △a j | △g | ▲h ☆a h | 2013 | |||||||||

| 2014 | ☆a | 2014 | |||||||||||

| 2015 | △bc | △a h ☆a | 2015 | ||||||||||

| 2016 | △bj | △c | △a | △bcj | △c | △a ☆a | 2016 | ||||||

| 2017 | △c | △b | △c | 2017 | |||||||||

| 2018 | △ad cj | △ch | △b | △ad cj | △c | ☆a | 2018 | ||||||

| 2019 | △d j | △ad cj | △ad | △bcj | △ad cj | ☆a | 2019 | ||||||

| Qualitative prescriptions | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport | Water | Healthcare | |||||||||||

| DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | DE | IE | IT | RO | ||

| 2009 | 2009 | ||||||||||||

| 2010 | 2010 | ||||||||||||

| 2011 | 2011 | ||||||||||||

| 2012 | 2012 | ||||||||||||

| 2013 | ♦a i | 2013 | |||||||||||

| 2014 | ◊2a h | 2014 | |||||||||||

| 2015 | 2015 | ||||||||||||

| 2016 | ◊a | 2016 | |||||||||||

| 2017 | ◊a | 2017 | |||||||||||

| 2018 | 2018 | ||||||||||||

| 2019 | 2019 | ||||||||||||

Categories: △ = resource levels; ☆ = coverage levels; ◊ = cost-coverage mechanisms.

Coercive power: ▲♦ = very significant; ![]()

![]() = significant; △☆ = weak.

= significant; △☆ = weak.

Semantic link to policy rationale: a = Enhance social inclusion; b = Rebalance EU economy; c = Boost competitiveness and growth; d = Shift to green economy; g = Expand labour market participation; h = Improve efficiency; i = Reduce payroll taxes; j = Enhance private sector involvement.

Bold letters = policy rationale linked to commodification script.

Country code: DE = Germany; IE = Ireland; IT = Italy; RO = Romania.

As the profitable segments of the Romanian water sector had already been privatised in the 2000s, EU executives focused their sector-specific prescriptions instead on the Romanian transport and health sectors. By contrast, EU executives focused their sector-specific prescriptions for Ireland on the water and healthcare sectors, as Irish governments had already turned Ireland’s public transport companies into formally independent, semi-state corporations. After 2008, Irish governments simply cut their subsidies to them, as part of their attempts to curtail public expenditure in general (Chapters 7 and 8).

Tables 11.3 and 11.4 show that EU executives issued only a few decommodifying prescriptions. Most of them appeared after 2016, tasking governments to invest more in transport and water but not in healthcare services. Despite their decommodifying orientation, most of these prescriptions did not question NEG’s commodifying logic. As in the case of the cross-sectoral prescriptions for public services (Table 11.2), the expansionary prescriptions for water and transport services had weak coercive power. They were also usually linked to policy rationales that were subordinated to an overarching logic of public service commodification. Finally, most expansionary prescriptions linked their calls for more resources for public services to the term ‘resource prioritisation’. This meant that any increase in public resources for some public services had to be matched with cuts elsewhere. In the following paragraphs, we compare NEG prescriptions for transport, water, and healthcare in more detail.

Curtailing Public Spending for Transport, Water, and Healthcare Services

The turn to austerity in general also curtailed public spending for the three public services sectors under consideration. EU executives thus issued sector-specific prescriptions that tasked governments to curtail the resource levels for specific public services as well as the coverage levels of specific public services that users could access.

In the water services sector, EU executives issued no commodifying prescription in the two quantitative categories, as Table 11.3 illustrates. In the transport services sector, EU executives issued such prescriptions only for Romania in 2011 and 2012. Even so, the Irish government, for example, cut its capital spending on transport services between 2008 and 2012 by 72 per cent and its current spending until 2015 by 31 per cent, as outlined in Chapter 8. Most sector-specific quantitative prescriptions that pointed in a commodifying policy direction affected healthcare services. Only Italy did not receive such prescriptions. Italian governments nonetheless cut €37 billion from Italy’s national health service between 2010 and 2019 (Chapter 10) and implemented significant commodifying healthcare reforms (Galanti, Reference Galanti2023) – once more highlighting the impact of the cross-sectoral prescriptions on resource and coverage levels in specific sectors.

EU executives issued specific commodifying prescriptions on public healthcare services, as ‘public expenditure on health absorbs a significant and growing share of EU countries’ resources’ European Commission, 2016b: 12, emphasis added). Romania received such prescriptions almost every year from 2010 until the advent of the Covid pandemic. When Romania was subject to very coercive MoU-related NEG prescriptions (2010–2013), EU executives tasked the Romanian government to contain hospital expenditure by reducing the overall number of hospitals and by reducing their bed capacity. Subsequently, EU executives tasked the Romanian government to make savings by shifting healthcare services from hospital to outpatient care (2016–2019). In 2013, Germany received a similar prescription, although EU executives never asked its government to curtail its public spending in general (see Table 11.1). In 2012 and 2013, EU executives tasked the Irish government to contain its health expenditure while the country was subject to a very constraining MoU.

In 2013, EU executives issued a prescription that tasked the Romanian government to ‘revise the basic benefits package’, curtailing the coverage levels of the public healthcare system for its users. As outlined in Chapter 10, these commodifying qualitative prescriptions led to deteriorating service levels, hospital closures, and a reduction in staffing levels, which in turn worsened the working conditions of healthcare workers as well as the welfare of patients in the public system. Incidentally, EU executives must have anticipated the negative effects of these measures on the public healthcare system too when they tasked the Romanian government in 2013 to ‘establish the framework for a private supplementary insurance market’ (Chapter 10). We return later in the chapter to this qualitative prescription.

In sum, given the dearth of commodifying quantitative prescriptions in the water and transport sectors (Chapter 7), the corresponding healthcare-specific NEG prescriptions do not simply mirror the application of austerity measures across all public services sectors. This becomes clear on assessing EU executives’ prescriptions for Germany (2013) and Romania (2016–2019) that tasked these governments to make savings by shifting healthcare from hospital to outpatient care at a time when the two governments were not tasked to curtail the resource levels for their public services in general (Tables 11.1 and 11.3). In the Romanian case, EU executives even issued prescriptions that simultaneously tasked the government to increase spending elsewhere, including in the water and transport sectors. This suggests that the NEG prescription drafters from the Commission’s DG ECFIN, quoted above, were not concerned primarily about public deficit figures (European Commission, 2016b: 12). More plausibly, the simultaneous calls for expansionary measures in other public sectors suggest that EU executives just assumed that public investments elsewhere would be more productive. The tension between allegedly (unproductive) social and (productive) economic services informing their NEG prescriptions is even clearer in the case of the decommodifying prescriptions in favour of greater public investment, which we discuss next.

Investing in (Productive) Public Services

Table 11.4 (as in Table 11.2, the superscript figures indicate the number of prescriptions in a given year; the superscript letters specify the semantic links between decommodifying NEG prescriptions and the policy rationales informing them) reveals that decommodifying NEG prescriptions in our two quantitative categories (resource levels and coverage levels) became more prevalent over time. Strikingly however, their unequal distribution patterns across sectors remained remarkably stable. As seen above, the commodifying prescriptions in these two categories targeted healthcare rather than water and transport services. Equally, the expansionary prescriptions that appeared after the alleged social investment turn in 2016 (Chapter 4) outnumbered the commodifying ones in the transport and the water but not the healthcare services sector. These sectoral differences are even more striking if we look also at the different policy rationales behind these decommodifying NEG prescriptions. Whereas NEG documents justified greater public spending on the network industries and their infrastructure as a productive, economic investment, this was not the case in healthcare. Regardless, the coercive power of all expansionary prescriptions was weak in almost all cases (Table 11.3).

The superscript letters accompanying the prescriptions in Table 11.4 specify the links between the prescriptions and the policy rationales informing them. The bold superscript letters on the right denote the semantic links to policy rationales that are compatible with the NEG’s overarching commodification script, whereas the nonbold superscript letters on the left indicate policy rationales that may deviate from this script.

Table 11.4 shows that the decommodifying prescriptions were linked to different policy rationales. This is not all that surprising, as decommodifying public policies can serve different objectives, such as ‘enhance social inclusion’ or a ‘shift to a green economy’. Policymakers created decommodifying public services also for economic reasons, for example to boost economic growth or to address market failures. Good examples of the latter can be found in public network industries that not only serve social goals but also provide key facilities for economic operators (Chapters 8–9). Europe’s public healthcare systems perform economic functions not only by contributing to the reproduction of labour in general but also by facilitating the greater participation of women and mobile workers in the EU labour market in particular (Chapter 10). Marianna Mazzucato (Reference Mazzucato2013) thus argued that the scope and scale of public services should increase in tandem with the creation of the EU’s internal market and monetary union.

As Table 11.4 reveals, however, only a few decommodifying prescriptions were linked to social and ecological policy rationales. The ‘shift to a green economy’ rationale came to the fore but only after the 2018 cycle and only in decommodifying prescriptions for the water and transport sectors. The ‘enhance social inclusion’ rationale had appeared earlier across all sectors in prescriptions for Romania on transport, water, and healthcare services. This is hardly surprising considering the exceptionally low share of Romanian households with access to running water and sanitation (Chapter 9) and the exceptionally low share of Romanian public healthcare spending as a share of GDP of 3.9 per cent in 2015 (as compared with 5.3 per cent in Ireland, 6.6 per cent in Italy, and 9.5 per cent in Germany) (OECD, 2023a). The coercive power of these social prescriptions was weak, however, unlike the MoU prescriptions that tasked the Romanian government to increase the co-payments of healthcare users (2010–2013) and to shrink the scope of health services covered by its public healthcare fund (2013). In the other three countries, EU executives linked their decommodifying NEG prescriptions only rarely to social policy rationales. Instead, they related them to rationales compatible with NEG’s commodifying script, as Table 11.4 shows.

Most expansionary NEG prescriptions targeted the infrastructure in the two network industries rather than in healthcare. After 2016, all four countries received such prescriptions, which stressed the contribution of greater investment to growth and increased competitiveness. In the German case, the expansionary prescriptions (2015–2019) were linked to the ‘rebalance the EU economy’ rationale, given the expected spill-over effects of a more expansionary public investment policy in surplus countries like Germany for the economies in the rest of the EU (see also section 11.2). After 2016, all four countries received expansionary prescriptions, albeit with a twist, mandating governments to prioritise infrastructure investment. This meant diverting public spending away from other areas towards infrastructure projects, inter alia, in the water and transport sectors.

In healthcare, Italy received a series of decommodifying prescriptions on resource levels to improve the provision of long-term care to incentivise greater labour market participation by women. Although the policy orientation of this prescription was decommodifying, it was linked to a policy rationale that does not question NEG’s commodification script. This becomes even more apparent when we consider the predominantly private provision of long-term care services in Italy and elsewhere (Chapter 10). In NEG prescriptions on transport and water services, the link between greater public investments and the need to enhance the involvement of the private sector in public services was even more explicit, as shown in Table 11.4. As in the case of their expansionary cross-sectoral prescriptions for the public sector, EU executives incentivised the channelling of public funds towards private firms in their sectoral prescriptions too. This commodifying logic is even clearer in their qualitative prescriptions for the three sectors, which we discuss next.

Marketising Transport, Water, and Healthcare Services

Tables 11.3 and 11.4 reveal an extremely consistent commodification pattern across all qualitative categories of NEG prescriptions. All prescriptions on the mechanisms governing the provision of services across all sectors and countries pointed in a commodifying policy direction. Apart from four prescriptions for Romania, the same was also true concerning the prescriptions on cost-coverage mechanisms, which specify the conditions for users’ access to public services.

As Chapters 8–10 discuss in detail, the degree of commodification of public services before 2008 varied from sector to sector and country to country. This explains the different deployment of marketising qualitative prescriptions across sectors and countries. In the transport sector, EU executives’ prescriptions on sector-level governance mechanisms targeted mainly the regulatory framework for railways in the member states. The existing EU railway laws still enabled member states to shield their state-owned railway companies to some extent from unbridled competition thanks to union protests and the ensuing amendments by the European Parliament and the Council of transport ministers, which curbed the commodifying bent of the Commission’s draft railway directives (Chapter 8). To overcome these limitations, the Commission and the Council of finance ministers issued railway-related prescriptions on a constant basis between 2009 and 2019 across all three countries, with the exception of Ireland – because Irish Rail arguably plays only a marginal role in EU transport networks. Hence, as Table 11.3 shows, EU executives sought to stimulate competition in the railway sector across the other three countries, regardless of their location in NEG’s enforcement regime. As much as the coercive power of the prescriptions differed across countries, their impact differed too. Whereas the Romanian government was constrained to implement almost all MoU-related prescriptions it received, the same did not happen in the German case, given the weak coercive power of the prescriptions for Germany (Chapter 8). Table 11.3 documents similar patterns pertaining to prescriptions on transport services in the provider-level governance mechanism category. Both Romania and Italy received prescriptions to implement railway privatisation plans, albeit with different degrees of vagueness, reflecting their unequal location in the NEG regime (Chapter 8). By contrast, EU executives did not issue any prescriptions that instructed the German government to privatise DB Cargo or its parent company Deutsche Bahn.

In the water sector, commodifying NEG prescriptions targeted the sector- and provider-level mechanisms too, as also the cost-coverage mechanisms governing Irish users’ access to water services. Only Romania did not receive any commodifying prescription for this sector, as its government had already privatised the lucrative water networks in the 2000s (Chapter 9). Whereas the MoU-related prescriptions tasked the Irish government to create a water corporation and to introduce charges for individual water users also, the less constraining prescriptions for Italy and the weak ones for Germany targeted the sectors’ governance mechanisms to marketise water services (Chapter 9). This happened although water was not, according to the EU Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC), ‘a commercial product like any other but, rather, a heritage which must be protected, defended and treated as such’ (Recital 1).

By contrast to NEG prescriptions in the area of employment relations and the healthcare sector, NEG prescriptions on water services were accompanied by simultaneous policy debates about a looming commodifying EU law, the EU Concessions Directive. This meant that water users and workers in all countries faced not only the same commodifying NEG script but also a looming EU law that would be, unlike NEG prescriptions, equally constraining across all countries. The same was not the case for public passenger transport services, which the Commission totally excluded from its Draft Concessions Directive, nor in health services, which the Commission at least excluded from its full application (Art. 5(g) and Recital 21 Draft Concessions Directive COM (2011) 897).

Compared with our other two public services sectors, healthcare services came within the reach of commodifying EU laws much later, as Chapter 10 outlines. This, however, did not stop EU executives from issuing commodifying NEG prescriptions on the mechanisms governing healthcare services. Romania’s and Ireland’s healthcare sectors in particular received several commodifying NEG prescriptions on sector- and provider-level governance mechanisms. This happened although European ‘Union action shall respect the responsibilities of the Member States for the definition of their health policy and for the organisation and delivery of health services and medical care’ (Art. 168(1) TFEU) – highlighting once more the fallacy of a too narrow, literal reading of such Treaty articles on the EU’s legislative competences in the sector and the importance of the EU executives’ political will. After all, Article 121 TFEU on multilateral surveillance and the ensuing Six-Pack of EU laws of 2011 allow corrective EU interventions whenever member states pursue policies that ‘risk jeopardising the proper functioning of the economic and monetary union’ (emphasis added) (Art. 121(4) TFEU), as discussed in Chapters 2 and 3. When subject to MoU conditionality, the Irish and Romanian governments received specific and very constraining prescriptions, which centralised control over hospitals’ budgets. Moreover, MoU-related NEG prescriptions forced the Irish government to shift the funding mechanisms for its hospitals from a system based on patients’ needs to a delivery-oriented case-based system. The latter prescriptions were particularly important from a commodifying healthcare policy perspective, as diagnosis-related group (DRG) funding methods are a precondition for the making of healthcare markets. Whereas Germany, Italy, and Romania had already introduced the DRG financing method before the EU’s shift to NEG, the Irish healthcare system lagged behind in this respect (Chapter 10). The governments of Ireland and Romania also had to introduce e-health systems, which are tellingly also needed for the operation of DRG healthcare financing methods. Conversely, the EU executives acknowledged the measures that the German government had taken earlier to improve the cost-efficiency of its hospitals and long-term care. They nevertheless asked the German government to go further, as the implemented reforms would be insufficient to contain the expected future healthcare cost increases. Promoting competition between healthcare providers was another regular theme in the prescriptions issued to Italy and Ireland. Finally, several MoU-related prescriptions on cost-coverage mechanisms committed the Romanian government to introduce co-payments for healthcare services (2010–2012) and to establish a private supplementary insurance market (2013), as mentioned earlier.

In contrast, and as Table 11.4 shows, decommodifying qualitative prescriptions were almost entirely absent, apart from four prescriptions for the Romanian healthcare sector that mandated the Romanian government to adjust health insurance contributions for low- and middle-income earners and to eradicate the practice of informal user payments to healthcare practitioners. Although the latter prescriptions pointed in a decommodifying direction, Romanian governments used them not to eradicate patients’ co-payments to access healthcare services tout court but rather to justify the replacement of informal by formal co-payments (Chapter 10). The prescription to adjust health insurance contributions for low- and middle-income earners was likewise linked to a policy rationale that does not collide with NEG’s overarching commodification script. The prescription benefitted the targeted workers as reduced payroll taxes increased their net pay, but, at the same time, it reduced companies’ nominal ULC. Altogether however, this measure once more reduced the funds available for public healthcare.

An Overarching Commodification Script across All Four Countries and Three Sectors

In sum, in all three public services sectors, all NEG prescriptions on both sector- and provider-level governance mechanisms pointed in a commodifying direction. Substantive deviations from this pattern occurred only when such prescriptions were not issued because of the implementation of earlier reforms (e.g., the prior introduction of the DRG healthcare funding method in Germany, Italy, and Romania or the prior privatisation of water services in Romania) or their irrelevance (e.g., railway services in Ireland). Given the countries’ different locations in the NEG enforcement regime, the overarching commodification script behind these qualitative prescriptions did not threaten the service users and workers in all four countries equally, except when prescriptions were accompanied by simultaneous draft EU laws, as happened in the case of the 2011 draft EU Concessions Directive. The same conclusion applies when we compare qualitative NEG prescriptions across the two cross-sectoral policy areas (employment relations, public services) and across the three public services sectors. All prescriptions across all four countries that tasked governments to implement structural reforms pointed in a commodifying policy direction across all years.

The more the public finances recovered from the financial crisis, the less constraining NEG prescriptions became. The slow recovery of European economies in the late 2010s led to an increase in prescriptions that pointed in a decommodifying policy direction, namely, quantitative prescriptions calling for greater public investments. Given their underlying rationales however, most decommodifying prescriptions were subordinated to NEG’s overarching commodification script. Certainly, labour movements and public service users very much welcomed the more expansionary NEG prescriptions. At the same time, our analysis reveals that EU executives’ NEG prescriptions mandated governments to channel more public resources into the allegedly more productive services (transport and water) rather than into essential social services like healthcare. Moreover, most decommodifying prescriptions on public service resources or wage levels were linked to commodifying rather than decommodifying policy rationales. Most importantly however, almost all qualitative NEG prescriptions pointed in a commodifying policy direction across the two policy areas, three sectors, and four countries, albeit with different coercive powers (depending on the countries’ location in the NEG’s policy enforcement regime) and in an asynchronous manner (depending on the prior progress of commodification in each site).

Our analysis has thus shown that the EU executives’ country-specific NEG prescriptions had less to do with the configuration of employment relations or public services in a country than with the location of its employment relations or public services on a commodification trajectory before NEG. The NEG regime could thus be described as a case of differentiated integration but not in the usual pre-NEG sense of EU laws that aim ‘to accommodate economic, social and cultural heterogeneity’ (Bellamy and Kröger, Reference Bellamy and Kröger2017: 625). Instead, EU executives’ country-specific NEG prescriptions followed a logic of reversed differentiated integration (Stan and Erne, Reference Stan and Erne2023; Chapter 3), as they targeted different countries differently to pursue an overarching commodification agenda.

This leads us to the question of whether NEG’s commodification script triggered an increase in transnational union and social-movement protests, or whether NEG’s country-specific nature (Chapter 2) effectively precluded an upsurge in transnational action. Given EU executives’ totalising aspiration to do everything necessary to ensure the ‘proper’ functioning of the EU economy and to put that in a few short policy documents, we assess whether the EU’s shift to NEG in turn prompted unions and social movements to respond to EU executives’ broad aspirations by broadening the scope of their own demands and by scaling up their countervailing collective actions.

11.4 NEG’s Commodification Script and Transnational Collective Action

In this section, we problematise the impact of the EU’s shift to NEG on European labour politics. We do that by assessing the patterns of transnational protests by trade unions and social movements in Europe on socioeconomic issues across two distinct historical periods. The first period spans the time from 1997, when the EU leaders agreed the original SGP in the run-up to EMU, until the advent of the financial crisis in 2008. The second period begins in 2009 and ends in 2019, that is, before EU executives opened a new era of NEG in March 2020 when they suspended the SGP’s fiscal constraints after the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic (Chapter 12).

We proceed with our analysis in two steps. First, we present and discuss our general findings, comparing the salience of transnational, socioeconomic protest events at company, sectoral, political, and systemic level across the two time periods. This comparison reveals that transnational protests targeting EU legislators (EU law) or EU executives (NEG prescriptions) clearly outnumbered the protests targeting private employers, national governments, European public employers, global trade agreements, or the transnational capitalist system in general. This highlights the salience of EU interventions as an important trigger of countervailing protests by trade unions and social movements and confirms that it is easier for them to politicise vertical EU interventions rather than horizontal market integration pressures.

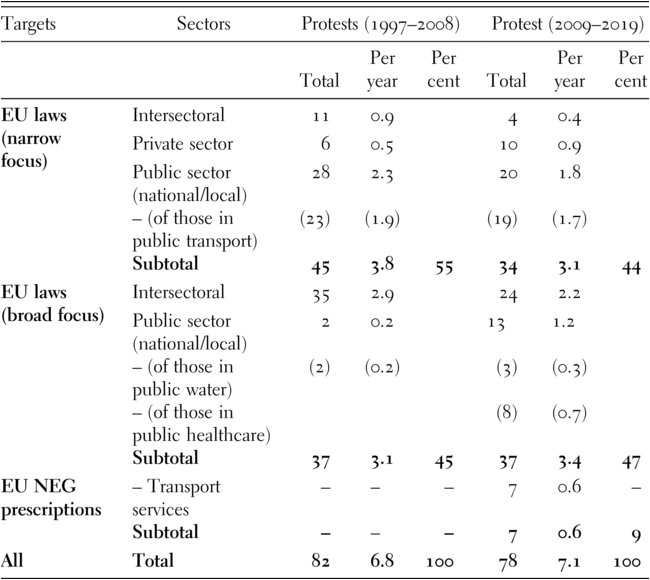

Second, we further differentiate the protests targeting EU legislators (EU law) or EU executives (NEG prescriptions) to assess in more detail the effects of the shift to NEG on labour politics. First, we split the protest category targeting EU law in two, distinguishing protests with a narrow focus on a particular law (e.g., EU Services Directive) from those with a broad focus on an entire thread of EU laws and policies (e.g., NEG regime). Second, we classify the protest events in the resulting categories by public service sector also. This allows us to relate the protests to the unequal patterns of commodification across public services sectors by specific EU laws, clusters of EU laws, and NEG prescriptions across the two distinct periods.

Transnational Protests on Socioeconomic Issues across Europe (1997–2019)

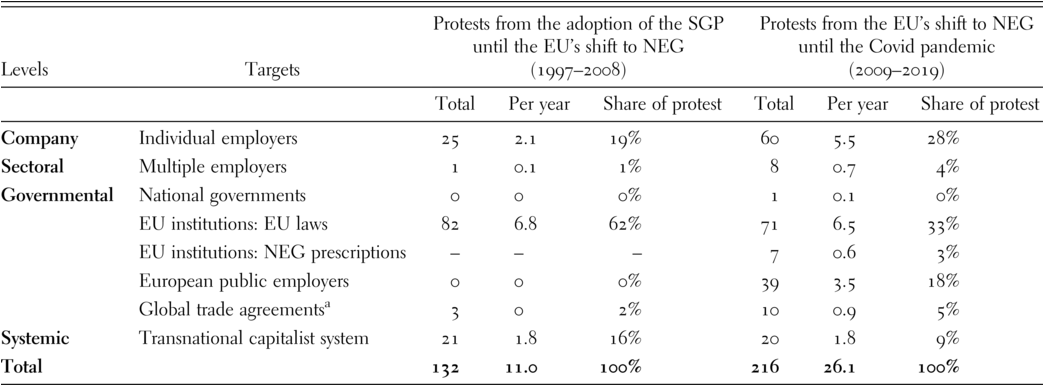

Table 11.5 confirms the key role of vertical EU interventions as a driver of transnational protests on socio-economic issues in Europe. In the pre-NEG period (1997–2008), we counted on average 6.8 such protests per year targeting EU institutions; this means that 62 per cent of all transnational protests belong to this political protest category (see Erne and Nowak, Reference Erne and Nowak2023). In the subsequent period (2009–2019), we counted roughly the same number of such protests per year, namely, on average 6.4 events per year targeting EU interventions by law and 0.6 events per year targeting NEG prescriptions.

Table 11.5 Transnational socioeconomic protests in Europe (1997–2019)

| Levels | Targets | Protests from the adoption of the SGP until the EU’s shift to NEG (1997–2008) | Protests from the EU’s shift to NEG until the Covid pandemic (2009–2019) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Per year | Share of protest | Total | Per year | Share of protest | ||

| Company | Individual employers | 25 | 2.1 | 19% | 60 | 5.5 | 28% |

| Sectoral | Multiple employers | 1 | 0.1 | 1% | 8 | 0.7 | 4% |

| Governmental | National governments | 0 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0.1 | 0% |

EU institutions: EU laws | 82 | 6.8 | 62% | 71 | 6.5 | 33% | |

EU institutions: NEG prescriptions | – | – | – | 7 | 0.6 | 3% | |

| European public employers | 0 | 0 | 0% | 39 | 3.5 | 18% | |

| Global trade agreementsFootnote a | 3 | 0 | 2% | 10 | 0.9 | 5% | |

| Systemic | Transnational capitalist system | 21 | 1.8 | 16% | 20 | 1.8 | 9% |

| Total | 132 | 11.0 | 100% | 216 | 26.1 | 100% | |

a This category includes protests that targeted the European Commission, which negotiates and signs global trade agreements.

If we add all political protests together, including those against the European Commission’s attempts to sign global trade agreements and those of European civil servants against their supranational public employers, the number of political transnational protests as a share of all transnational protests remained roughly at similar levels during the two time periods (1997–2008: 64 per cent; 2009–2019: 59 per cent). This is noteworthy, also considering the significant increase in transnational protests overall after the 2008 crisis, from on average 11.0 (1997–2008) to on average 25.9 (2009–2019) transnational protests per year. Before assessing the patterns of transnational protests targeting EU legislators and executives and their relationship to the EU’s shift to NEG in detail, we must explain the dearth of transnational protests targeting employers in the private sector. The latter is all the more puzzling as there are more transnational corporations (TNCs) than supranational governmental institutions in Europe, meaning that the number of protests targeting the former should, all other things being equal, be greater.

Explaining the scarcity of ‘private’ transnational protests on socio-economic issues: In 1999, labour-friendly scholars were already advising European trade unions to ‘enlarge their strategic domain to keep workers from being played off against each other’ (Martin and Ross, Reference Martin and Ross1999: 312). Nonetheless, most scholars of labour politics predicted that collective bargaining, social policymaking, and, thus, also union action would remain confined to the nation state (Thelen, Reference Thelen, Hall and Soskice2001). Although greater economic and monetary integration would put unions and social policies under increased horizontal market pressures, these competitive adjustment pressures would not end the autonomy of national labour policymakers, at least not formally. Accordingly, social pacts and other national corporatist arrangements reappeared in the 1990s – albeit for novel reasons, for example, to enhance a country’s competitiveness or to help it meet its EMU convergence criterion of low inflation (Chapter 6). Certainly, European unions tried to coordinate their bargaining policies across borders to curb the pursuit of beggar-thy-neighbour strategies, but these attempts largely failed (Erne, Reference Erne2008). Thus, labour politics remained more a national than a European affair (Dølvik, Reference Dølvik, Martin and Ross2004). Mirroring the varieties-of-capitalism paradigm in political economy and labour studies (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001), most European trade unions stressed the advantages of national coordinated employment relations systems, including in export-oriented industries. Although the corresponding competitive corporatist arrangements involved concession bargaining, it gave union leaders a seat at policymaking tables. However, the more transnational horizontal market dynamics put national bargaining systems (designed to take wages out of competition) under pressure, and the more the senior management of TNCs used whipsawing tactics that put workers from different sites in competition with one another (Greer and Hauptmeier, Reference Greer and Hauptmeier2016), the more hitherto combative national industrial unions adopted collaborative stances to increase the competitiveness of ‘their’ production sites and companies. Transnational union protests against private employers occurred only very rarely, namely, when management adopted very uncompromising stances and union activists found levers in the EU institutional framework that they could use as a catalyst for transnational action (Erne, Reference Erne2008; Golden and Erne, Reference Golden and Erne2022). The making and enlargement of European goods and capital markets as such did not trigger transnational protests, as shown by the low number of protests targeting employers at company or sectoral level (see Table 11.5). However, whereas the increased transnational horizontal market pressures and the whipsawing games of TNCs allowed corporate executives to contain labour movements, EU executives were not as effective in preventing transnational protests by unions and social movements.

Explaining the salience of political transnational protests on socio-economic issues: In the 2000s, EU executives started to propose ever more EU laws that attempted to commodify both labour and public services. This is important, as EU labour law had hitherto pointed in a decommodifying direction (Chapter 6) and public services had been shielded from horizonal (market) integration pressures triggered by the making of the European single market (Chapters 7–10).