There is an increasing body of research evidence on what factors contribute to the aetiology of mental illness. Reference Picchioni and Murray1 In the aetiology of schizophrenia, a range of social and psychological factors have been suggested, including childhood abuse, Reference Bebbington, Bhugra, Brugha, Singleton, Farrell and Jenkins2 parenting style/expressed emotion, urban stress, Reference Sundquist, Frank and Sundquist3 inequality Reference Boydell, Van Os, McKenzie and Murray4 and abnormal thinking styles. Reference Bentall, Fernyhough, Morrison, Lewis and Corcoran5 A meta-analysis suggested a greater importance of cognitive than biological variables. Reference Heinrichs6 Similarly, depression appears to have a multifactorial aetiology with research supporting the role of genetic, Reference Kendler and Prsecott7 biochemical and endocrine, Reference Goodwin, Gelder, Lopez-Ibor and Andreasson8 psychological, Reference Freud and Strachney9,Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery10 and social factors. Reference Brown and Harris11

Some work has explored patients’ explanatory models of illness. Reference Angermeyer and Klusmann12-Reference Jorm, Christensen and Griffiths14 Yet little is known about the views of psychiatrists, how consistent they are and to what degree they reflect current evidence. If it is the case that treatment satisfaction and therapeutic relationships are influenced by (mis)match in doctor–patient explanatory models of illness, Reference Callan and Littlewood15,Reference McCabe and Priebe16 psychiatrists’ views are as relevant as patients’ views. The aim of this study was to identify the views of practising British psychiatrists on the aetiology of depression and schizophrenia, the variation of aetiological factors from patient to patient, and the importance of asking patients about their understanding of illness.

Method

Sample

A postal survey was sent to a random sample of consultant psychiatrists in July 2006. The names of all 1677 British consultants registered with the Royal College of Psychiatrists as specialising in general and adult psychiatry were organised alphabetically and a sample of 335 (20%) was selected by identifying every fifth name. Non-responders were sent a second questionnaire 3 months later.

Questionnaire

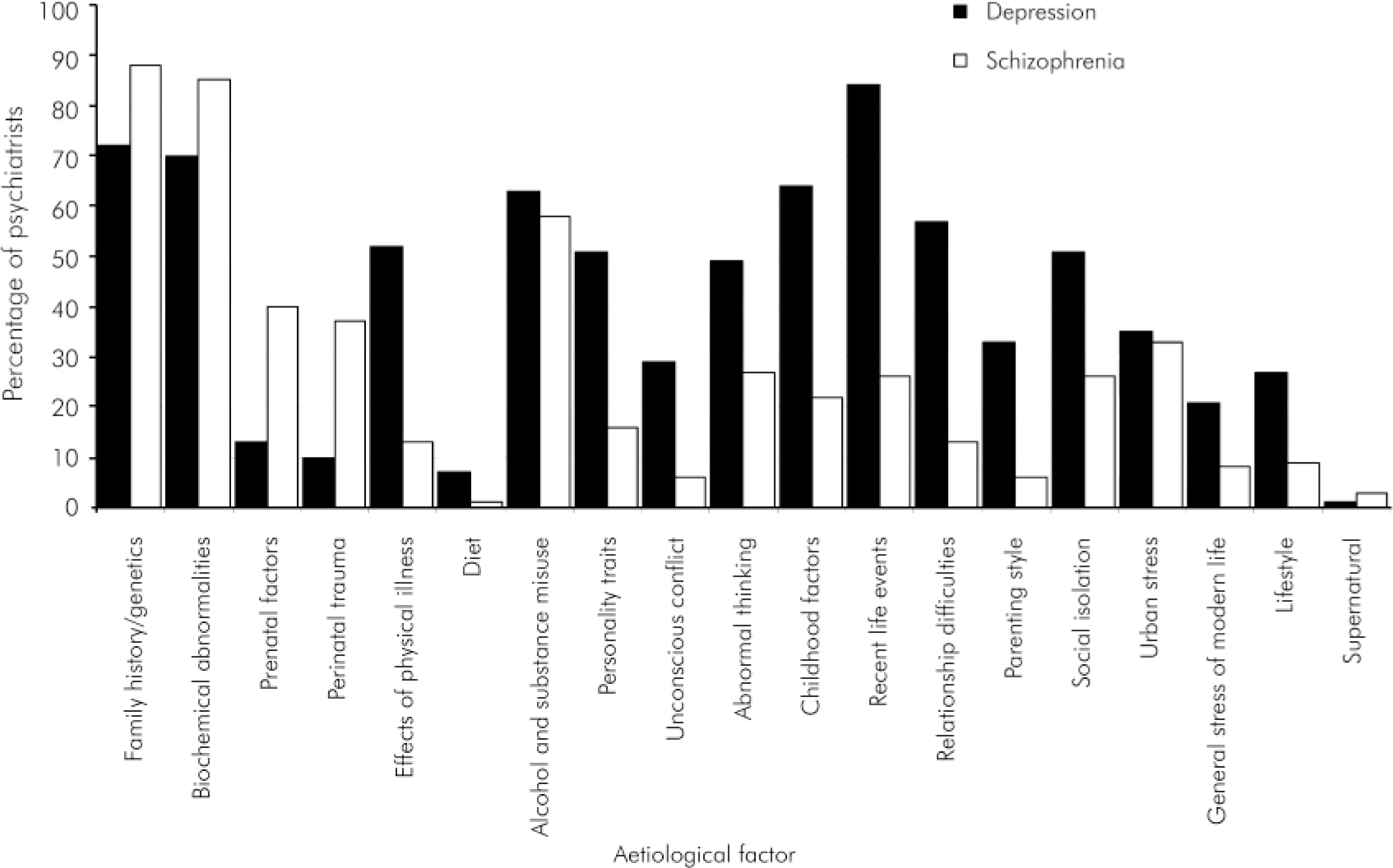

A questionnaire on the aetiology of depression and schizophrenia was adapted from Angermeyer & Klusmann Reference Angermeyer and Klusmann12 and piloted locally. It presented a list of 19 putative aetiological factors (Fig. 1) and asked the participants to rate: (a) for each factor, their importance on a five-point Likert scale (from 1, ‘definitely not a cause’ to 5, ‘definitely a cause’) for the aetiology of depression or schizophrenia in a patient with a typical form of each disorder; (b) how much these vary from patient to patient; and (c) how important it is to ask patients about their understanding of their illness (an open question).

The study was approved by the local research ethics committee.

Statistics

Results are presented as percentages of respondents who felt that a given factor is relevant (as shown by choosing point 4 or 5 on the five-point Likert scale) or are described as means. Significant differences between proportions were tested using Pearson's chi-squared test and differences between means using independent samples t-tests (SPSS, version 13 for Windows). Answers to open questions were analysed for content.

Results

Seven questionnaires were returned as the named clinician no longer worked at the address and 154 of the remaining 328 psychiatrists (47%) responded to the questionnaire. Respondents were on average 47.0 years old (s.d. = 8.5) and 17.5 years (s.d. = 7.9) since postgraduate qualification; 69.6% were male. Two-thirds (76.6%) described themselves as White, 15.5% as Asian, 1.9% as Black, 3.9% as coming from other ethnic background and 1.9% did not respond to this question.

The results are summarised in Fig. 1. Genetics, biochemical abnormalities and alcohol/substance misuse were considered important in both depression and schizophrenia. Beyond that, there was considerable heterogeneity in psychiatrists’ views. For example, for the aetiology of depression, as many considered parenting style important as non-important; for the aetiology of schizophrenia, as many considered urban stress important as non-important. Depression was viewed as a more multifactorial condition with psychological/social factors considerably more important, whereas biological factors were more important in schizophrenia.

Aetiological factors of depression

Nine factors were more important in depression than schizophrenia. All save one (the effects of physical illness (including pregnancy) χ2 = 99.7, P < 0.001) were psychological or social: recent life events/loss (χ2 = 104.875; P < 0.001); relationship difficulties (χ2 = 62.053; P < 0.001); parenting style (χ2 = 33.547; P < 0.001); childhood factors (including neglect and abuse) (χ2 = 53.111; P < 0.001); social isolation (χ2 = 19.689; P < 0.001); unconscious conflict (χ2 = 26.022; P < 0.001); abnormal thinking/thinking errors (χ2 = 16.847; P < 0.001); general stress of modern life (χ2 = 6.803; P = 0.009); and lifestyle (χ2 = 41.263; P < 0.001).

Fig. 1. Percentage of responding psychiatrists rating each factor as relevant to the aetiology of depression or schizophrenia.

Aetiological factors of schizophrenia

Only four factors, all biological, were more important in schizophrenia than in depression: genetics (χ2 = 12.085; P < 0.001); biochemical abnormalities and neurotransmitter dysfunction (χ2 = 10.0152; P = 0.001); prenatal factors (χ2 = 29.15; P < 0.001); and perinatal trauma (χ2 = 30.699; P < 0.001).

Variability of aetiological factors

Aetiological factors were thought to vary more among patients with depression compared with those with schizophrenia (4.51 v. 4.01, P < 0.001).

Discussing patients’ views

It was also deemed to be significantly more important to ask patients with a diagnosis of depression about their understanding of their illness than those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (4.79 v. 4.61, P = 0.008).

The reasons given by psychiatrists on why it is important to ask about patient's understanding of their illness included:

-

• to develop an individual treatment plan in collaboration with the patient (49.6% for depression v. 36.4% for schizophrenia, P = 0.03) – ‘treatment needs to be tailored to the patient's needs, keeping in mind their personal views’;

-

• to achieve treatment adherence (20.9% v. 28.7%, P not significant (n/s)) – ‘to come to a shared model that will ensure adherence to treatment’;

-

• to influence prognosis (8.2% v. 8.5%, n/s) – ‘patient's perception regarding their understanding of their illness has a bearing on outcome’;

-

• to influence the therapeutic relationship as an active therapeutic ingredient in its own right rather than simply mediating better adherence Reference Day, Bentall, Roberts, Randall, Rogers and Cattell17 (11.2% v. 25.6%, P = 0.002) – ‘patients experiencing psychosis attach meaning to that experience: understanding this allows us to collaborate better in the long term’;

-

• for purposes of assessment, including assessment of insight and psychological mindedness (10.4% v. 15.5%, n/s) – ‘to establish if there is any insight into causative factors and the development of the illness’;

-

• to gain a shared formulation (21.6% v. 14%, n/s) – ‘so that the patient and I have a better understanding of precipitating factors and events’;

-

• for the purposes of education (13.4% v. 12.4%, n/s) – ‘for psychoeducation’.

Discussion

The most striking finding of this study is the heterogeneity of psychiatrists’ views on factors playing a role in the aetiology of depression and schizophrenia. Genetics and biological abnormalities were considered important by more than two-thirds of the sample in both conditions. However, beyond that there was little consistency in views with nothing ruled completely out or in. To illustrate this inconsistency, genetic factors were not rated by all of the sample, whereas supernatural factors were rated by some psychiatrists, albeit only a handful.

A clear result is that depression is viewed as a more multifactorial condition than schizophrenia and that psychological and social factors are deemed to be more important. Moreover, psychiatrists feel it is more important to discuss aetiological factors with patients with depression and that those factors are more likely to vary from patient to patient than in schizophrenia.

Limitations

Considering the limitations of this study, although our 50% response rate is usual for a postal survey, we cannot assume that these results would generalise to all general adult psychiatrists. In addition, we used a standardised questionnaire that relied on lists of potentially crude categories (e.g. personality traits) which may mean different things to different respondents. This may have introduced some random error, thus reducing the direct comparability of results across respondents. The questionnaire also asked respondents to consider a typical patient and patients vary widely in clinical practice.

Do these views reflect the evidence or interpretation of the evidence? It is not so much that biological factors differ between depression and schizophrenia but that psychological/social factors are acknowledged by many more psychiatrists in depression but not in schizophrenia. Interestingly, urban stress is the one exception, a psychological/social factor of equal importance in depression and schizophrenia, which might reflect findings of higher morbidity in urban areas. Reference Sundquist, Frank and Sundquist3

Clinical implications

Although this is not a study of the evidence per se, it is a valid picture of psychiatrists’ perception of what matters aetiologically and may reflect what will be conveyed to patients in clinical practice. It may be a reason to consider more flexibility in matching patients to doctors with similar explanatory models. How do psychiatrists’ views compare with those of patients? In relation to schizophrenia, 66% of patients cite psychosocial stress as causative, whereas 27% thought heredity and 29% other biological causes relevant. Reference Holzhinger, Kilian, Lindenbach, Petscheleit and Angermayer18 When encountering psychiatrists, patients with schizophrenia are likely to meet a different mindset than if they had a diagnosis of depression. This may not complement their own views on causative factors in their illness, which has implications for ongoing treatment planning and management.

That psychiatrists consider biological factors as more important in the aetiology of schizophrenia may have several underlying reasons. It has been suggested that aggressive and misleading psychiatric drug promotion reinforces perceptions of biological causes to mental illness, Reference Moncrieff19 although it is not obvious why this should affect the views on schizophrenia more than those on depression. Considering schizophrenia as more biologically determined than depression is arguably a traditional view in psychiatry, which may both influence and result from the stronger research focus on biological factors in schizophrenia, Reference Toone, Murray, Clare, Creed and Smith20,Reference Clement, Singh and Burns21 and the limited provision of psychological treatments for patients with schizophrenia. Our findings are more congruent with an ad hoc survey at the annual American Psychiatric Association meeting in 1987 where 63% of participants predicted that within 25 years the diagnosis of schizophrenia would be replaced by a specific biologically defined disease category. Reference Angermeyer and Klusmann12

In mental illness, perceived biological aetiology is associated by lay persons with increased perceived unpredictability, dangerousness and social distance, Reference Dietrich, Beck, Bujantugs, Kenzie, Matschinger and Angermeyer22 compounding stigma and undermining the rationale of recent anti-stigma campaigns. If schizophrenia is considered to have a predominantly biological aetiology, this has considerable implications on how patients diagnosed with this condition are perceived and treated. That these assumptions are also held by psychiatrists is an issue that may need to be addressed in training and practice.

Conclusions

What psychiatrists actually think about the aetiology of mental disorders and the importance of asking patients about their views will have an impact on practice more than the research evidence. This study shows that psychiatrists vary widely in their views and hold disorder-specific views, which means that patients are likely to encounter different views depending on their illness and their psychiatrist. This has clinical relevance that could be addressed in training and practice. With increasing specialisation, patients often experience multiple moves between different teams and treating psychiatrists. Awareness that it is not just patients but also psychiatrists who hold quite varied views regarding the aetiology of mental illness may make it more possible to sit with the considerable uncertainty regarding the cause of chronic mental disorder, and allow open and frank discussions with patients, which may enhance therapeutic relationships and recovery.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.