Background

Indigenous populations who live in colonised nations with a non-Indigenous majority are at significant disadvantage. Although these populations vary in cultural practices, language and lore, they share disadvantage that has resulted from the direct and indirect impact of colonisation, including separation from culture, identity, land, language, stigmatisation and discrimination.Reference Stewart1–6 On average, Indigenous people have lower socioeconomic status,7–14 poorer health8,15–Reference Reading and Wien19 and a shorter life expectancy than their non-Indigenous counterparts.15,20–22 Violent victimisation and trauma is underreported, but is also higher in Indigenous communities,23–26 and is compounded by vicarious experience of trauma by other community members and by stories about ancestors' experiences.Reference Holland, Dudgeon and Milroy27,Reference Maurtiz, Goossens, Draijer and van Achterberg28

It should not therefore be surprising that Indigenous people in colonised nations have poorer mental health,26,Reference King, Smith and Gracey29–31 increased risk of substance misuse26,Reference King, Smith and Gracey29,Reference Durie32,33 and higher rates of suicide.8,26,34,35 More broadly, these communities tend to have poorer social and emotional well-being – a more holistic concept encompassing physical and mental health, family, community, connection to land, culture and spirituality, which are seen as closely interlinked.Reference Zubrick, Shepherd, Dudgeon, Gee, Paradies, Scrine, Dudgeon, Milroy and Walker36

One important aspect of relative disadvantage and discrimination is an overrepresentation of Indigenous people in prison,37–Reference Reitano40 which is consistently seen in colonised Western nations (USA – Native American and Alaskan Native 1% general to 2% prison population;41 New Zealand – Māori 15% general to 51% prison;42 Canada – First Nation People, Métis and Inuit 3% general to 27% prison;43 Australia – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 3% general to 28% prison37,44 ). This group is at particular risk of trauma and poor mental health.Reference Fazel and Seewald45,Reference Heffernan, Andersen, Dev and Kinner46

Researching and addressing the needs of Indigenous people in custody

There is therefore both an acute need and a moral imperative to develop effective interventions to address the needs of Indigenous people in custody. Specifically, there is a need for interventions specific to the different Indigenous groups of these jurisdictions, which incorporate that cultural group's understanding of well-being and mental health, and are delivered in a mode that is culturally relevant and acceptable. Such interventions tend to have higher participant engagementReference Castro, Barrera and Martinez47–Reference McGough, Wynaden and Wright50 and effectiveness.51–Reference Rix, Barclay, Wilson, Stirling and Tong54

Existing reviews of mental health interventions for prisoners or community offenders typically focus on the general population rather than on Indigenous or First Nations people,Reference Abbott, Lloyd, Joshi, Malera-Bandjalan, Baldry and McEntyre55–Reference Sherman, Strang, Mayo-Wilson, Woods and Ariel62 and other reviews of interventions for vulnerable populations may include some Indigenous people or prisoners, but do not focus on Indigenous prisoners.Reference Bryant, Bonevski, Paul, McElduff and Attia63–Reference Wilson, Guillaumier, George, Denham and Bonevski66 Only one Indigenous-specific review on prisoners was identified, but that focused on prisoners' needs when transitioning back to the community, rather than on interventions for Indigenous prisoners more generally.Reference Abbott, Lloyd, Joshi, Malera-Bandjalan, Baldry and McEntyre55

Aims

The aim of the current systematic review was therefore to examine published evaluations of interventions that were delivered specifically for Indigenous people in prisons operating under dominant non-Indigenous models of health and justice.

Method

Search strategy and data extraction

A search was conducted to identify articles published in peer-reviewed English language journals to August 2019 that reported qualitative or quantitative evaluations of interventions to address well-being or mental health issues in Indigenous adults in custody. Papers were excluded if they only described programmes or their uptake, focused only on predictions of outcome, or if the intervention was solely medical. To ensure as comprehensive a review as possible, randomisation or a control group was not required. The review encompassed Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the USA – four nations where substantial Indigenous populations live under a colonised, Western model of justice and health.

Searches were conducted using Scopus, Web of Science (Web of Science Core Collection, Current Contents Connect, Data Citation Index, Derwent Innovations Index, MEDLINE, SciELO Citation Index), PubMed, PsycNET (PsycINFO, PsycArticles, PsycBooks), EBSCO (CINAHL Plus, Criminal Justice Abstracts), Proquest Criminal Justice Database and Informit (Adaft, Humanities and Social Sciences Collection, Health Collection, Indigenous Collection, Family and Society Collection, New Zealand Collection). Articles between 1948 and August 2019 were included. The search terms were: (Indigenous or indigenous or native* or Native* or Māori or Maori or Aborigin* or aborigin* or “Torres Strait Island*” or “torres strait island*” or “first nation*” or “first people*” or Inuit or Metis or Métis) AND (jail* or gaol* or custod* or prison* or imprison* or incarcerat* or corrections or correctional or offend* or inmate*) AND (intervention* or program* or treatment* or treat* or therap* or service* or prevent* or diversion* or initiative*) AND (wellbeing or “well being” or mental or depress* or anx* or suicide* or trauma* or alcohol* or drinking or cannabis or cocaine or methamphet* or amphet* or substance* or addict* or heal* or empower* or grief or loss* or stress* or psychosis or psychoses or psychotic or resilien* or recovery).

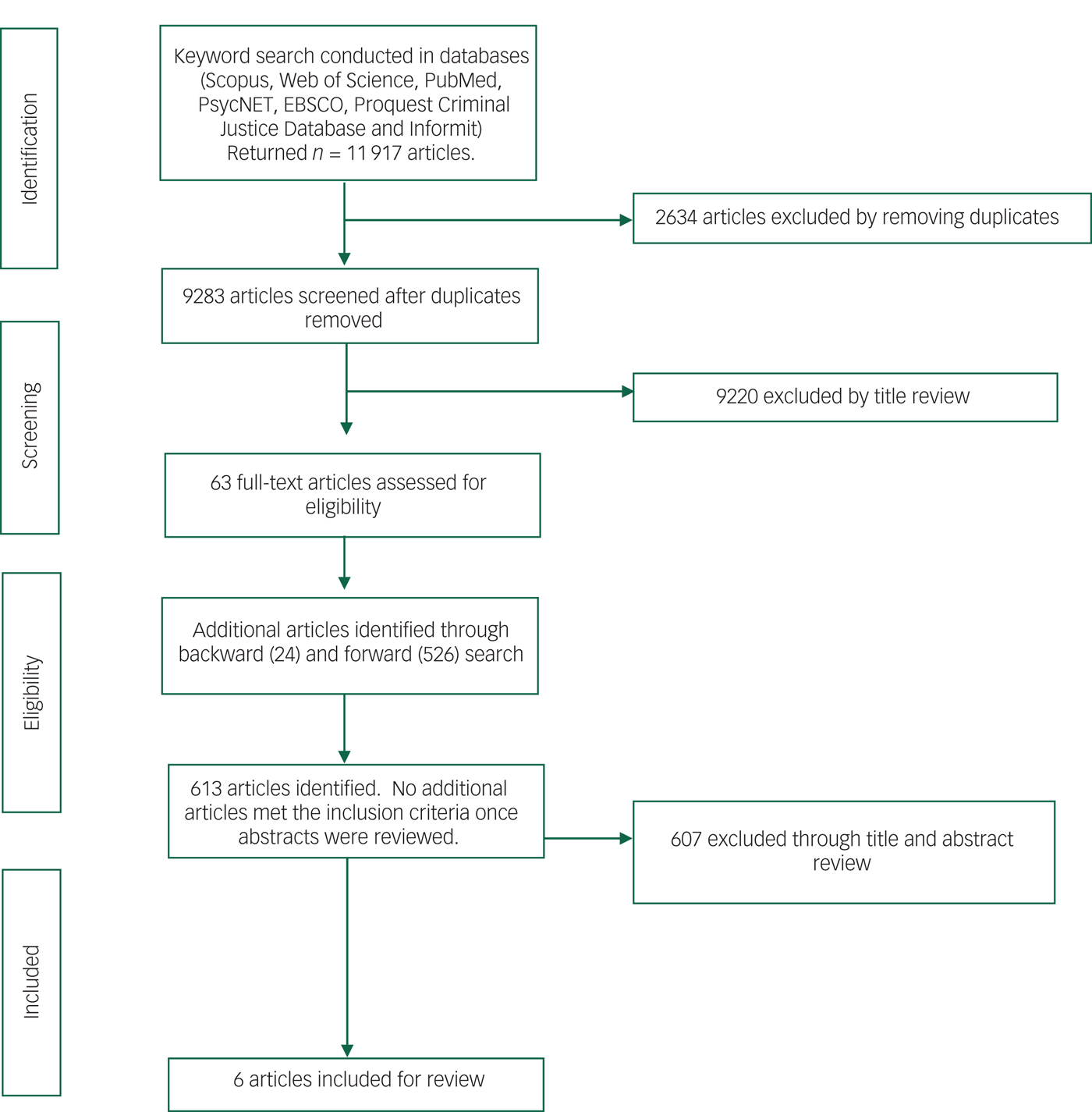

Results of the initial search were imported into Endnote X9.2 and duplicates were removed. Titles, then abstracts and finally full-text articles were reviewed to identify and exclude studies that did not meet inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Forward and backward searches were then undertaken to see if additional studies could be identified. Data extraction and initial screening of titles was conducted by the first author (E.P.). E.P. and D.K. independently screened the remaining abstracts and full papers against inclusion criteria to determine what would remain for full-text review. There were no disagreements on inclusion.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of the literature search strategy.

Study quality

The Effective Public Health Practice Project's Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (EPHPP;67 https://merst.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/quality-assessment-tool_2010.pdf) was used to assess the methodological quality of quantitative evaluations in this review. Each article was rated against the six EPHPP components (selection bias, study design, control of confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals/dropouts), providing a global rating of either strong, moderate or weak in methodological quality. The EPHHP was developed for use in public health research. It demonstrates fair interrater agreement over individual components and excellent agreement over the final global rating.Reference Armijo-olivo, Stiles, Hagen, Biondo and Cummings68

Quality appraisal of qualitative evaluations was undertaken using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Research Checklist (CASP),69 a tool recommended by the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group.Reference Hannes, Noyes, Booth, Hannes, Harden, Harris and Lwein70 The CASP's criteria (aims, methodology, design, recruitment strategy, data collection, researcher/sample relationship, ethical issues, data analysis, statement of findings, value of research) allow the derivation of an overall assessment of a study's quality as strong, moderate or weak.Reference Hodgins, Gnich, Ross, Sherriff and Worlledge-Andrew71 Evaluations were graded as weak if they did not meet both of the first two criteria, and as moderate or strong based on the remaining eight criteria. For both EPHPP and CASP, after independent ratings, reviewers discussed ratings with discrepancies and reached consensus.

Results

Identified studies

The search identified 9283 titles after removal of duplicates, and screening of titles and abstracts refined relevant papers to 63. Forward and backward searches were conducted using these papers, but no additional papers met the inclusion criteria after review of their abstracts. A review of the full text of the 63 articles identified only 6 that met criteria for inclusion in the review (Fig. 1; Table 1), two of which described the same study. No randomised controlled trials were identified. Three studies involved a quantitative follow-up – in two cases with a comparison group – and two were qualitative (one using only interviews whereas the other had interviews and a focus group).

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; FU, follow-up; BL, baseline; NS, not specified.

a. All samples involved incarcerated participants.

b. Unclear if community release dependent upon participation in programme or in the case of the parenting programme, child access.

c. Affiliated with Diné Centre for substance misuse treatment.

d. When data were available at both 3 and 9 months, 3-month data were used. Baseline data on some variables were not available for some followed-up participants (NS).

e. Convenience sample of parents who attended the Babiin-Miyagang programme, and who agreed to be interviewed at times researchers could attend.

The papers were published between 1997 and 2017. Two studies were conducted in Canada, one in the USA and two in Australia. Four interventions (the ‘Ending Offending’ programme, ‘Navajo Sweat Lodge’ ceremonies, ‘Tupiq’ programme and ‘Babiin-Miyagang’ programme) focused on identified treatment needs. The remaining intervention (‘Native Sisterhood Sweat Lodges’) involved the use of traditional ceremonies for women that were described to participants as recreational.

All five of the reviewed studies demonstrated the feasibility of providing interventions that were specifically for Indigenous people and facilitated by Indigenous people, within a high-secure prison environment. All of them demonstrated changes in well-being, and those that measured reoffending also reported some indications of improvement. Although the two qualitative studies had a moderately strong methodology, the three quantitative studies were methodologically weak (Table 2).

Table 2 Methodological ratings of quantitative studies in the review

a. Insufficient information to justify a higher rating.

b. The study appears to have tracked the subsequent offending history of all participants in the Tupiq and alternative programmes who had been released at the time when data collection occurred.

Table 3 Methodological ratings of qualitative studies in the review

a. Insufficient information to justify a higher rating.

b. Two raters independently reviewed transcripts and the research team discussed emerging themes. The extent that any contradictory data and the researchers' role were considered is not reported.

c. Consent was by exchange of tobacco, as negotiated with members and elders. No committee approval is described.

d. Rated only by the researcher, using records in a reflective journal rather than transcripts. However, used nVivo and describes disagreement.

Intervention outcomes

Ending Offending

The Ending OffendingReference Crundall and Deacon72 programme focuses on treatment of alcohol misuse in Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander adult alcohol users, applying principles of harm minimisation. Although the programme is Indigenous specific, it was adapted from a non-Indigenous one. The primary changes to the programme were to language, methods of self-monitoring alcohol consumption and construction of groups in accordance with tribal and kinship rules.

The intervention group in the study, who were Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander men, showed significantly greater post-release rated improvements in alcohol consumption, violent or disruptive behaviour, family relationships, time meaningfully occupied, general health, ability to cope and being responsible. However, each of these ratings used a single item with a five-point scale (with ‘no change’ as the midpoint and end-points not reported). The men also showed greater improvement on trouble with the law (on a three-point scale – less, no change, more) and association with people who drank (on a five-point scale from did not drink/keeps more sober company to drinks with big drinkers). It was not clear how many intervention and control participants were approached to be in the study, and no check was undertaken to determine if groups were matched on previous alcohol consumption or criminal history. The specific Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander nations or language groups to which participants belonged were not specified.

Navajo Sweat Lodge ceremonies

The Navajo Sweat Lodge ceremoniesReference Gossage, Barton, Foster, Etsitty, LoneTree and Leonard73 also focused on addressing alcohol misuse, linking American Navajo and Diné traditional practices with Indigenous-specific psychoeducation and group therapy. Sweat Lodge ceremonies involve a sauna-like experience, where physical suffering is combined with prayers and songs to the Creator. Although there was a drop-in alcohol consumption in the intervention group post-release, it was not statistically significant (effect size not published; Table 2). The Native American tribes or linguistic-cultural groups of the programme participants were not specified.

Tupiq (Inuit sexual offender programme)

The Tupiq programmeReference Stewart, Hamilton, Wilton, Cousineau and Varrette74 targeted sexual offending in Canadian Inuit prisoners assessed as being at moderate to high risk of sexual reoffending. A case–control study (n = 61 intervention; n = 114 control) demonstrated significantly lower rates of general and violent reoffending in the treated group. Sexual reoffending was not differentially reduced (P = 0.16 without covariates; P = 0.30 with covariates; Table 2), but its base rate was low and 28% of the control group had received previous treatment for it. The risk factors for sexual offending of prior sexual offences and having male victims were not controlled for in these analyses. The Inuit tribes or cultural-linguistic groups of the study participants were not detailed within the paper.

Babiin-Miyagang (parenting) programme

The Babiin-Miyagang programmeReference Rossiter, Power, Fowler, Jackson, Roche and Dawson75 aimed to strengthen parenting and leadership skills of Aboriginal Australian men, and address kinship and social responsibilities to children and young men in their communities. Programme modules covered: being a dad today; understanding our kids; yarning; keeping our kids safe; and coaching our kids.Reference Rossiter, Power, Fowler, Jackson, Roche and Dawson75 Prisoners were excluded from participation if they were experiencing serious mental health issues, had current convictions for sexual offending or were under child protection orders. No quantitative outcomes were reported, but themes from qualitative interviews reflected an appreciation of an opportunity within a culturally safe environment to reflect on how to connect with their children; how to be a role model within their communities; and their culture. As in the preceding studies, the paper did not detail the Aboriginal Australian nations or linguistic-cultural groups to which participants belonged.

Native Sisterhood ceremonies (sweat lodges)

This study aimed to identify effects of Native Sisterhood ceremoniesReference Yuen and Pedlar76 (and particularly of sweat lodges that were similar to ones in Gossage et al (2003)),Reference Gossage, Barton, Foster, Etsitty, LoneTree and Leonard73 on Canadian First Nation, Inuit and Métis female prisoners' cultural and emotional healing. Themes in the evaluation of cultural healingReference Yuen and Pedlar76 included participants' experience of marginalisation leading to their offending behaviour; prison providing them with an opportunity to learn about their culture; ceremony providing opportunity for self-discovery and exploration of participants' own Indigenous heritage; the opportunity of turning shame in their heritage to pride through ceremony; the need for cultural support upon release; and their concern about continued discrimination and exclusion upon release, leaving women marginalised by society. Themes in the evaluation of emotional healingReference Yuen77 included healing of trauma, in part because of the psychological freedom from the prison environment (even though sweat lodges were within the boundaries of the prison). A second theme involved participants' preference for addressing well-being issues with Canadian First Nation, Inuit and Métis practitioners and elders through a more holistic and traditional manner than was available from non-Indigenous health professionals. Weaknesses in the papers included an absence of details on recruitment or quantitative outcomes. However, the study was able to demonstrate the importance of a temporary physical alteration of the prison environment to support a culturally informed Indigenous-specific intervention. The paper noted that participants had Ojibwe, Cree, Mi'Kmaq, Mohawk or Inuvik ancestry, but did not further specify the tribes to which they belonged.

Grey material, including programme descriptions

An examination of grey material identified several further examples of relevant well-being and offender rehabilitation interventions (see supplementary Table 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.80). As expected, ones provided by correctional services had a greater focus on offender rehabilitation, whereas ones delivered by health services had a greater focus on mental health and well-being. Within the jurisdictions reviewed, the only publicly available internal agency evaluations identified were those published by the Corrective Service of Canada. These available evaluations were of interventions targeting Indigenous prisoners' well-being (Healing LodgesReference Trevethan, Crutcher, Moore and Mileto78); substance misuse (Aboriginal Offender Substance Abuse Program;Reference Kunic and Varis79 Native Offender Substance Abuse Pro-Treatment ProgramReference Weekes and Millson80); general offending (Circles of ChangeReference Thompson81); sexual offending (Inuit Sex offender ProgramReference Stewart, Hamilton, Wilton, Cousineau and Varrette82,Reference Trevethan, Moore and Naqitarvik83 ); and violent offending (Spirit of Warrior ProgramReference Bell and Flight84; In Search of Your WarriorReference Trevethan, Moore and Allegri85; see supplementary Table 1). Across these internal agency evaluations, there was both a range in the publicly available detail and a range in the methodological quality. Although literature indicated that there have been internal agency evaluations of interventions within the jurisdictions such as New Zealand and Australia, no additional evaluations of either could be accessed for review.

In New Zealand, all offender rehabilitation programmes are designed under an Indigenous cultural framework.39,42,Reference Campbell86 Australia also has a range of Indigenous-specific programmes, although they vary considerably in nature and availability across states and territories (see supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

It seems that it is possible to deliver culturally based well-being and offender interventions specifically for Indigenous people within a high-secure prison environment, although the lack of robust evaluations of those programmes means that as yet there is no firm evidence base to support their use. In particular, the review found no controlled comparisons of the relative impact of Indigenous-specific and generic well-being programmes for Indigenous prisoners. Research of this kind is needed to provide further substantiation of the need to offer Indigenous-specific interventions.

Implications for design and delivery of culturally safe interventions

Despite the limited nature of the research in this review, some principles for design and delivery of culturally safe interventions may be derived. Although the five studies identified within this review had disparate aims, content and delivery methods, all employed culturally sensitive practices, and demonstrated an awareness, if not implementation, of cultural protocols. They all aimed to address barriers to intervention that are exacerbated by stigma and the lack of trust in dominant non-Indigenous services. Perhaps most importantly, these studies illustrate the potential benefits of having interventions delivered or supported by Indigenous facilitators. The cultural knowledge of Indigenous facilitators or elders appears to reduce some of the barriers to client engagement that are otherwise seen in prison-based interventions.Reference Abbott, Lloyd, Joshi, Malera-Bandjalan, Baldry and McEntyre55,Reference McMurran87–Reference Bowler, Phillips and Rees89 Indigenous facilitators are more likely to have a shared understanding of a client's culture and life experience, which supports the delivery of a culturally responsive well-being and mental health service.Reference Shepherd90 This cultural sensitivity appears to be of particular importance when providing cultural and trauma healing, as seen in the fifth study.

Although the current body of research is not yet able to support the contention that culturally sensitive interventions have a differentially greater benefit than alternative ones, it is implausible that interventions that did not meet this criterion would either be acceptable or have a positive impact. In fact, less culturally sensitive models run the risk of maintaining or exacerbating alienation and distress. We already know from other research, that people are more likely to be receptive to accessing health messages and interventions from people they relate to and respect; that are delivered in a narrative that mirrors their life experience and values; that align with people's cultural beliefs and lore; are delivered in a language that is clearly understood; and that are viewed as credible and effective.Reference Lundell, Niederdeppe and Clarke91–Reference Ashdown, Treharne, Neha, Dixon and Aitken94

That is not to argue that all culturally sensitive interventions will have a sustained impact on either well-being or reoffending. One approach that may have benefit could be to examine interventions that have been shown to have effect in other groups, looking for parallels with the cultural beliefs and practices of the tribe or nation, and for acceptable delivery modes and language. Examples in the reviewed papers included the Ending Offending, Tupiq and Babiin-Miyagang interventions, which integrated a combination of Western and Indigenous content with a delivery mode that was familiar and acceptable to the specific group.

Another example, currently under trial by the authors, involves a waitlist control comparison evaluation of the Aboriginal and Islander Mental Health Initiative Stay Strong Plan (SSP) application (app). This digital mental health project aims to evaluate the utility of the Indigenous-specific SSP app with Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander people incarcerated across three high-secure prisons. The SSP is a structured mental health and substance misuse brief assessment and intervention tool developed to enhance people's social and emotional well-being.Reference Dingwall and Nagel95 This tool is being used as part of an Indigenous-led and delivered in-reach prison social and emotional well-being service, working solely with Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander people.

Implications for policy

Given the overrepresentation of Indigenous people within the four reviewed jurisdictions and the fact that descriptions of Indigenous-specific interventions in prison environments are given in a range of papers and reports, the identification of only five evaluated programmes raises questions about people's access to evidence-based interventions for mental health and well-being, and the barriers both to undertaking and publishing evaluations of these interventions.

To the extent that Indigenous prisoners lack access to culturally safe evidence-based well-being and mental health interventions, this is of significant concern. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Article 24 states, ‘Indigenous individuals have an equal right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. States shall take the necessary steps with a view to achieving progressively the full realisation of this right’.96 An inability for First Nation people in prison to access this human right should therefore be a driving force for agencies and government commitment to address the issue as a high priority.

Success in reducing the disparity in mental health and well-being of Indigenous prison populations across the jurisdictions reviewed within this paper, is limited; with the prison population experiencing further isolation, stigma and lack of access to culturally responsive interventions than people in the community. Social justice requires that we, as practitioners and agencies, provide protection to vulnerable people such as First Nation people in prison. This role includes redressing the determinants of poor social and emotional well-being and the effects these have upon people's well-being, mental health, quality of life, resilience and recidivism. Social justice requires an increase in equity-oriented evidence-based interventions from implementation through evaluation and a shared knowledge in the field of what is entailed in effective intervention.

Ensuring that culturally appropriate services for the well-being and mental health of all incarcerated First Nation peoples requires policies and practices that underpin that aim, and that are supported by sufficient financial investment and close, respectful collaboration with members of relevant Indigenous communities who can assist with the design, delivery and evaluation of those services. Until that occurs, examples like those in the current review will remain isolated and highly vulnerable to discontinuation, unable to offer equitable access, and subject to the attitudes, competencies and priorities of current staff in a particular facility.

Barriers to evaluation and publication

A review of grey material across the jurisdictions examined in this paper identified several other examples of Indigenous-specific interventions within prisons, which have not yet led to peer-reviewed publication of evaluations (see supplementary Table 1). The question then raised is, what are the barriers to evaluating these interventions and sharing their outcomes publicly?

A roundtable of prison health service directors identified core barriers specific to conducting health research within a prison environment as access to prisoners, staff attitudes towards research, research literacy within practitioners and agencies, and agencies' concern over negative findings being published.Reference Simpson, Guthrie and Butler97 Also, prison policy and the population has repercussions for the methodology of research projects, as the nature of a prison and prison population means that it can be difficult to separate out the true effect of individual intervention factors from other determinants and to have control comparison groups (who are untreated), which would be required for a true randomised control trial. This is particularly important in the evaluation of offender behaviour and well-being interventions as withholding mandated treatment is not a possibility and interventions that could reduce a client's symptoms of mental ill health would be unethical. It is because of this, that when evaluations are undertaken of prison interventions, researchers are likely to rely on quasi-experimental designs.Reference Bulman, Garcia and Hernon98 A combination of these factors can provide an explanation as to some of the barriers to conducting and publishing thorough and unbiased evaluations of prison-based interventions.

While First Nation people are overrepresented in the jurisdictions discussed in this review, with the exception of New Zealand, First Nation people are a minority subpopulation of the broader prison population. We have an environment within prison research in which we have finite resources typically targeted to the containment and treatment of the majority population, reducing the capacity and focus on interventions for Indigenous prison populations and the evaluation of interventions targeted specifically to them.

Another barrier to publication involves the results of the evaluations. For both in-reach and insider research, value to the agency has to be proved in order to undertake research but also for permission to publish. Should evaluations of interventions prove non-significant or negative then approval may not be given to publish as they may incur resourcing consequences to government-delivered services. For correctional agencies, there is also the risk of legal challenges should decisions about release from prison be made based upon participation in offender interventions that then go on to be shown to be ineffective.Reference Hannah-Moffat99 This risk-averse approach to evaluations and publications may in part explain the low publication rate of evaluations. This management of reputation can also extend to community expectations of correctional and health agencies to manage, supervise and treat offenders. Government agencies may be reluctant to evaluate or publish based upon a political decision to maintain community faith in services being provided.

Limitations

The current review was limited by the small number of published evaluations and the methodological limitations of these evaluations. It was not possible to identify a consistent pattern of components across effective well-being and mental health interventions delivered specifically for Indigenous people in custody.

Articles that did not meet the final inclusion criteria and available agency material demonstrated that each of the jurisdictions examined by this paper have examples of Indigenous-specific well-being and or mental health interventions for people in custody (see supplementary Table 1). If peer-reviewed evaluations have been conducted on these interventions they were not published in the literature available through the current search. There may be unpublished evaluations that could provide valuable information on what is effective and ineffective in addressing well-being and mental health needs for Indigenous people in custody, but those were not available for review.

Implications for future research

First Nation prisoners are an especially vulnerable subpopulation, given the fundamental restriction upon the autonomy of people in prison.Reference Spencer100 Any intervention trials with the different First Nations groups across these jurisdictions requires the assurance of participants' rights, including an assurance that participants do not join other Indigenous populations in becoming overresearched with minimal benefit.Reference Kendall, Sunderland, Barnett, Nalder and Matthews101 To ensure benefit of research to Indigenous people, researchers must incorporate culturally safe processes and recognition; benefit to the community; capacity building in Indigenous researchers; time taken in community consultation and relationship building; and community participation and ownership of data.102–105

Future research should also explore stronger collaborations between prison authorities, forensic mental health services and both Indigenous and other academics in the conduct of rigorous trials of mental health and well-being interventions for incarcerated Indigenous people. As noted above, the involvement of prison authorities is critical to facilitating the conduct and publication of research. Forensic mental health services carry the primary responsibility for delivering effective mental health and well-being interventions that address prisoners' treatment needs, whether clinical or criminogenic. The benefit of research that supports evidence-based practice needs to be marketed to agencies as a pathway through which they can prevent ineffective interventions in a field of vulnerable people, meeting the needs of protection of the community and improving the quality of prisoners' lives. The involvement of academic researchers can supplement the research expertise of prison authorities and mental health services in the conduct of rigorous evaluations. Universities have a vested interest in industry engagement to ensure tertiary programmes are relevant and current for students, in the same way that agencies, directly or indirectly require university research programmes to support their need for evidence-based practice.

There is a particular need for randomised controlled trials in this area. Where the interventions are delivered individually, it may be possible to randomly allocate different prisoners to contrasting interventions, although there remains a risk of contagion where prisoners are able to talk about their experiences. Where group-based or whole-unit interventions are offered, it may sometimes be necessary to randomly allocate comparable units. If there is concern that all prisoners should have access to a particular intervention, a stepped-wedge design may be used, where a comparator is given to one or more groups before they receive the focal intervention. Discussion of the contextual constraints and valued outcomes by all parties before finalising the experimental design is likely to facilitate institutional and ethical approvals and maximise engagement of staff, while maintaining scientific rigour.

In conclusion, our initial aim in this review was to identify the core components and characteristics of effective Indigenous-specific well-being and mental health interventions in custody. The overall lack of published evaluations and the limitations of available evaluations meant that this was not achievable. Evaluations with stronger methodologies are required to draw out patterns of effective interventions and service delivery models; patterns that better inform practitioners' work in improving the well-being and mental health of Indigenous people in custody.

This review has become an opportunity to encourage research in practice by quantifying the lack of evaluations and summarising the barriers unique to publishing evaluations of prison-based Indigenous well-being and mental health interventions. Existing research has summarised the needs, identified the gap and now calls for increased delivery and evaluation of these interventions.

Governments and prison authorities are under a moral obligation to address the disparity in mental health and reduced access of incarcerated First Nation people to evidence-based culturally responsive and clinically competent interventions. This task requires both the evaluation and international dissemination of these interventions to encourage greater international communication about this key social justice issue. The current review therefore calls for greater support for practitioners evaluating interventions, continued collaborative support between agencies and academia, and publication of evaluations by agencies to support the field more broadly in their delivery of effective evidence-based well-being and mental health interventions for Indigenous people in custody.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.80.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.