Introduction

Significant events in our societies have the power to modify our emotional systems and change what we think or what we do. Secessionism and the possibility of modifying national boundaries are events that impact the social order and the individuals’ feelings. This paper aims to find evidence of human response to those emotions associated with the sense of belonging to a nation. We use the example of two Spanish regions, Catalonia and the Basque Country, where different nationalist parties launched their separatist strategy fifteen years apart (Heller, Reference Heller2002). We evaluate how voters’ relevance to distinct issues and values is reflected when exposed to secessionist pressures. The Spanish case is not an isolated example; nationalist movements are present in nations such as Belgium, Canada, Denmark, India, Italy, Pakistan, and the UK, where, occasionally, the separatist goal surfaces in an overt effort to secede (Brancati, Reference Brancati2006, Reference Brancati2014). Spain’s analysis sheds light on the mechanism with which regionally based parties (and possibly, populist parties) can influence our emotional system and affect vote choices.

When a region seeks to leave a nation, we explore what ideas or values are activated within the electorate of that region. The comparison of two Spanish regions, Catalonia and the Basque Country, provides the perfect case study. In these similar regions, separatist efforts of the dominant nationalist parties did not coincide in time (Conversi, Reference Conversi1997; Olivieri, Reference Olivieri2015; Medrano, Reference Medrano1995). The Basques pursued independence from Spain in the 2001 Regional Elections, and the Catalans intensified secessionist efforts in the 2015 Regional Elections. We estimate the average weights that citizens assign to each issue dimension when deciding their vote. We measure the relevance of self-interest and group-identity issues in voters’ preferences during six consecutive elections from 1998 to 2016. Importantly, we seek shifts in the salience of the issues during the periods where the regions intensified their separatist efforts. We interpret that such shifts reveal the underlying values activated in voters’ minds when exposed to secession. Notably, we cannot determine the causal effect that links voters’ reactions to parties’ strategies. Instead, we provide evidence of voters’ reactions when exposed to secessionist pressures. Footnote 1

Methodologically, we propose an empirical model to estimate the salience of several issue dimensions that determine vote choices. The underlying random utility model is based on the spatial model of voting initiated by Downs (Reference Downs1957). Issue-salience is a broad concept that studies the importance attached to issues as a policy attitude (Krosnick, Reference Krosnick1990; Krosnick and Petty, Reference Krosnick and Petty1995). Usually, the salience of an issue is understood to respond to actual events, policymakers’ decisions, and media agenda-setting (Dennison, Reference Dennison2019). Instead of analyzing reported responses to the most important issues or most important problems (Bartle and Laycock, Reference Bartle and Laycock2012), our study measures, from a behavioral perspective, the relative weights attached to issues when making vote decisions. We explore voting responses as a function of parties’ positional and valence issues. Thus, our main concern is the average relevance that individuals assign to policy issues, whether self-interest or group-identity issues (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Krosnick, Fabrigar, Krosnick, Chiang and Stark2017).

We explore a data set including 23,800 and 28,600 personal interviews to the pre- and post-regional election surveys for the Basque Country and Catalonia, provided by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). Footnote 2 The surveys contain similar questions in both regions on perceptions about the economic assessment, individuals’ positions on the left-right and nationalist dimensions, language usage, national identity, and vote choice. Our contribution combines the theoretical framework of the spatial voting model and the extensive dataset provided by the CIS to explore how voters in two similar regions react to parties’ secessionist movements. The proposed theoretical framework can be applied to every democratic election where positional and valence issues are determinants of vote choice and where analysts aim to explore voters’ reactions to actual events.

Interestingly, our analysis reveals that secessionist efforts in Catalonia and the Basque Country manifested in a deeper division of voters along two lines, urban-rural location and national identity. In line with Hatton (Reference Hatton2016), our study shows that issue-salience, when directly measured in voters’ behavioral responses, is not a stable but a volatile concept. Unexpectedly, we find no evidence of voters expressing additional concerns about economic discontent, left-right differences, or degrees of autonomy for the region. By contrast, when elections focus on separatism, the identity associated with the local language and the regional culture, along with the urban-rural divisions, are factors that gain relevance to explain vote choice. We interpret that separatism produces an emotional reaction that increases voters’ importance towards those group-identity issues related to culture and customs.

The political science literature has independently developed theories explaining secessionist movements and others analyzing vote choices through issue selection. Our contribution brings these two strands of the literature together to show that secessionist efforts reflect on voters’ relevance to different issue dimensions.

Secessionist theories describe the mechanisms dividing modern nation-states. A relevant explanation is an expected improvement in economic conditions, connected to the poor performance of central government politicians and the anticipation of the positive impact on the region of forming a new independent state (Hierro and Queralt, Reference Hierro and Queralt2021). Various authors suggest this line of argument for the Quebec secessionist movement (Blais and Nadeau, Reference Blais and Nadeau1992; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Kornberg and Stewart2004; Boylan, Reference Boylan2015), but others have discarded the economic argument as an argument of Catalan nationalism upturn (Cuadras-Morató and Rodon, Reference Cuadras-Morató and Rodon2019). Footnote 3 A different explanation is related to identity and the feelings of becoming more attached to their representatives, flag, and other cultural symbols (Collier and Hoeffler, Reference Collier, Hoeffler and Hannum2011; Sorens, Reference Sorens2012). For instance, speaking the regional language has been shown to impact the electoral support of secessionist parties (Gellner, Reference Gellner1983; Sorens, Reference Sorens2005) and the construction of new states (Laitin, Reference Laitin1988; Laitin et al., Reference Laitin, Solé and Kalyvas1994). Footnote 4 Former studies of the Basque region (by Costa-Font and Tremosa-Balcells, Reference Costa-Font and Tremosa-Balcells2008) and Catalonia (by Serrano, Reference Serrano2013; Muñoz and Tormos, Reference Muñoz and Tormos2015; and Rodon and Guinjoan, Reference Rodon and Guinjoan2018) point to national identity and language as determinants of self-reported responses to a hypothetical referendum on separatism. Footnote 5 Unlike Scotland and Quebec, the Spanish Constitution does not envisage referendums on self-determination. Thus, secessionist tensions reflect in regional elections.

On the other hand, the literature on issue selection explores how political parties compete on political issues through emphasizing the matters on which the party has an advantage (Riker, Reference Riker and Riker1993), or by better handling some political issues (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996), or a combination of both (Bélanger and Meguid, Reference Bélanger and Meguid2008). From a theoretical perspective, an increasing number of authors establish a relation between particular issues and voting behavior (Borre, Reference Borre2001). Recent theories explore how campaign strategies modify the average relevance that voters assign to distinct political issues (Dellis, Reference Dellis2009; Amorós and Puy, Reference Amorós and Puy2013; Aragonés et al., Reference Aragonès, Castanheira and Giani2015; Dragu and Fan, Reference Dragu and Fan2016; Denter, Reference Denter2020). While the empirical measure of the salience of political issues is a broad topic of interest (Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1977, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Ansolabehere et al., Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder2006; Gelman, Reference Gelman2008; Iyengar and Kinder, Reference Iyengar and Kinder2010), these analyses have not examined so far the impact of separatist strategies on the weights that voters assign to different issue dimensions. We fill this gap by exploring the salience of self-interests and group-identity issues when regional parties pursue independence.

Previous analyses on secessionist votes explore global samples where each observation is a region (e.g. Sorens, Reference Sorens2004, Reference Sorens2005) or an ethnic group (e.g. Saideman and Ayres, Reference Saideman and Ayres2000). In those studies, regional or ethnic characteristics such as percentage of the population speaking the local language, group size, or local growth rate are independent variables that impact the regional vote share for secessionist parties. Our individual-level analysis explores group-specific characteristics, instead of attributes of the region, that explain vote choice in times of separatist pressures.

The rest of the paper organizes as follows. The following section explains the Basque and Catalan case studies, their party systems and economies. We then present our theoretical model and the empirical analysis We devote a subsequent section to measuring issue-salience. Finally, we provide the conclusions.

The Basque and the Catalan case studies

The politics surrounding the separatist movements in the Basque Country and Catalonia provide an ideal comparison for testing theories of secession and regional identity (Conversi, Reference Conversi1997, Reference Conversi2000). The two Autonomous Communities have similar economies, comparable histories (both were on the same side of civil wars in the 19th and 20th Centuries), and analogous party systems. Our comparative strategy exploits the fact that separatist efforts in these regions have not coincided in time, and the leadership of the dominant nationalist parties has alternated periods of integration and separatism. The President of the Basque Government, member of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (PNV), launched a secessionist proposal and tried to validate it in the 2001 Basque Elections. This separatist movement lost its strength in 2009 when its leader lost the Basque Presidency. On the other hand, Catalan nationalist parties collaborated with the Spanish Government until 2010, when the Spanish Constitutional Court struck down parts of the regional 2006 Statute of Autonomy for this region. The Catalan secessionist movement activated, and the President of the Catalan Government, member of Convergencia y Unión (CiU), launched a separatist strategy that tried to validate in the 2015 Catalan Elections.

We explore vote choices in six consecutive regional elections between 1998 and 2016. Previous to such analysis, this section compares the party system and the economy of these regions to discard the possibility of other sources of variability within the regions that could be affecting voters’ responses in these regions.

Party systems

The electoral system in the Basque and the Catalan Parliaments is proportional representation. In each region, there is a dominant political party. In the Basque Country, since the approval of the Spanish Constitution in 1978, the PNV has held the Basque Presidency for all but three years, from 2009 up to 2012, when the Euskadi Socialist Party (PSE) got the Presidency. In Catalonia, CiU has governed for more than 20 years, from 1980 up to 2003. After this period, the Catalan Socialist Party (PSC) held the Catalan Presidency for two legislatures from 2003 until 2010 and, in the 2010 Elections, CiU was reelected.

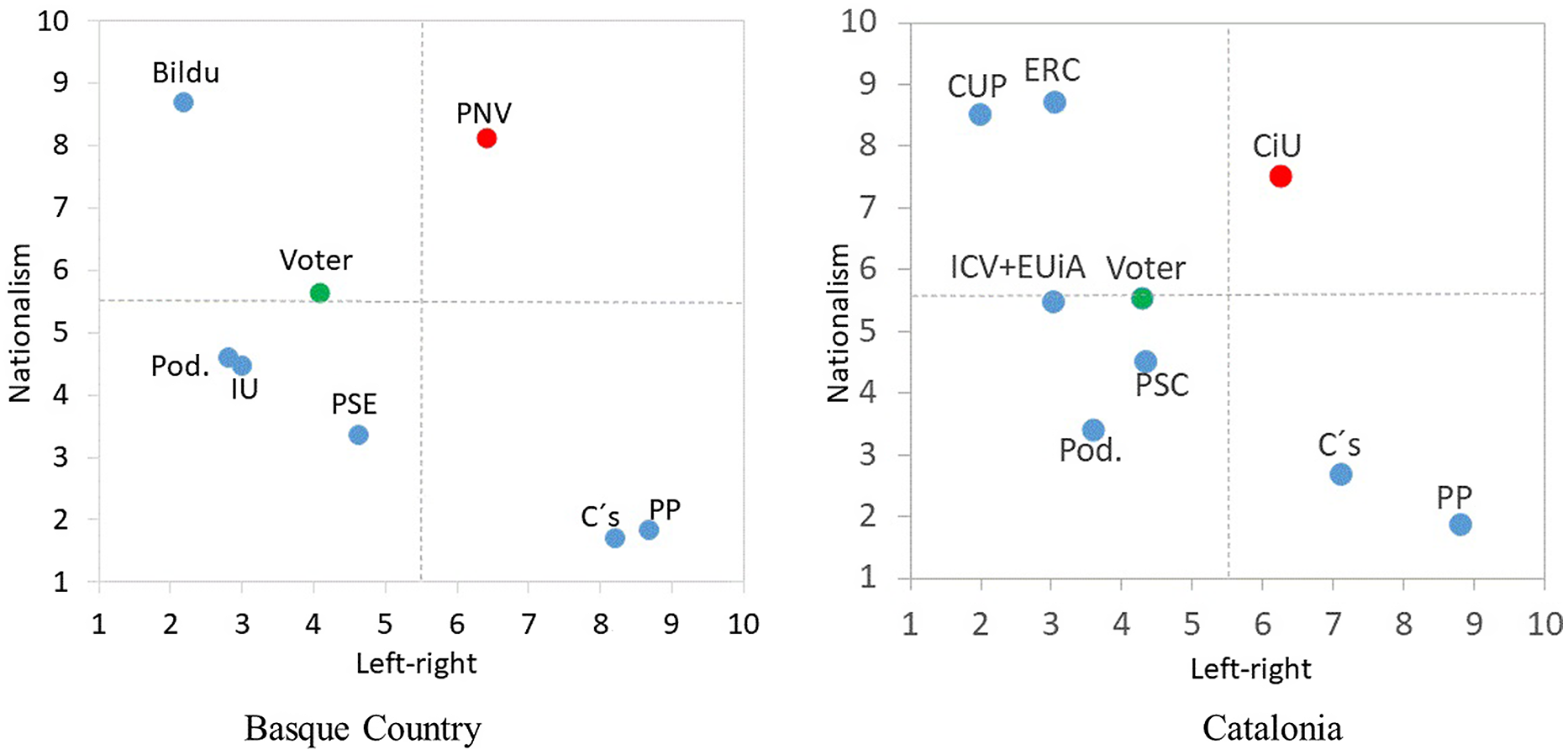

We plot in Figure 1 the average perceived position of the parties in the left-right and nationalism dimensions for the period 1998–2016 according to the post-electoral surveys run by the CIS. Footnote 6 The left-right dimension represents the ideological position of parties regarding their degree of interventionism in the economy or its socialist versus conservative values. Responses are reported on the 1 to 10 scale, where 1 means extreme left and 10 means extreme right. Footnote 7 Nationalism is understood as the degree of political decentralization from national politics. Responses are reported on the 1 to 10 scale, where 1 means complete centralization (or minimal autonomy for the region) and 10 means maximal decentralization (or full autonomy for the regional government). Footnote 8

Figure 1. Average parties’ perceived positions for the period 1998–2016.

We compare the positions of the parties in these regions and deduce relevant observations:

First, the dominant parties in the regions, PNV and CiU, occupy a similar center-right nationalist position with no other close party.

Second, in both regions, the left-nationalist quadrant is occupied by Bildu in the Basque region and ERC in Catalonia (in the Basque region, this left-nationalist party renamed on several occasions as EH and PCTV). Footnote 9 Other smaller parties occupy a more extreme position in this quadrant, the CUP in the 2012 and 2015 Catalan elections and Aralar in the 2005 and 2009 Basque elections.

Third, since 2015, nationwide parties have competed with other close parties. The PP competes with C’s to dominate the right non-nationalist quadrant, and the socialist parties (PSE and PSC) compete with Podemos and minor left-wing parties (IU, ICV+EUiA) for the left non-nationalist quadrant.

Fourth, in both regions, the average respondent holds a center-left position with an intermediate nationalist position (labeled as ‘Voter’ in Figure 1). Besides, the average respondent in each region is slightly more leftist than the two strongest nationwide parties, PP and the socialists, and in between the main nationalist parties in their left-right dimension. Footnote 10

Regarding vote shares, the nationalist parties have regularly added more than 50 percent of votes in the Basque region. This percentage reached its maximum in the 2012 regional election when nationalist parties captured about 60 percent of votes. In Catalonia, the nationalist vote (including CiU, ERC, and CUP) reached its maximum of 48 percent of votes in the 2012 and 2015 elections. Footnote 11 Remarkably, the 2001 Basque election confronted two blocks, the constitutionalists with the Spanish People’s Party (PP) and the PSE on the one side, and the separatists with PNV and EH on the other side. Similarly, the 2015 Catalan elections confronted similar blocks, Junts pel Sí (J×Sí) that joined all the pro-independentist parties except for CUP on the one side, and the constitutionalist parties PSC, PP, and C’s on the other side. Notably, lower nationalist percentages of votes preceded these secessionist movements in the regions. Low vote shares may have motivated nationalist parties to strengthen their separatist efforts. However, this is a conjecture that we cannot test. We find that elections regularly worked in both regions before the 2001 Basque and 2015 Catalan elections. Thus, other uncommon electoral motives did not affect voters in these elections.

Economic indicators

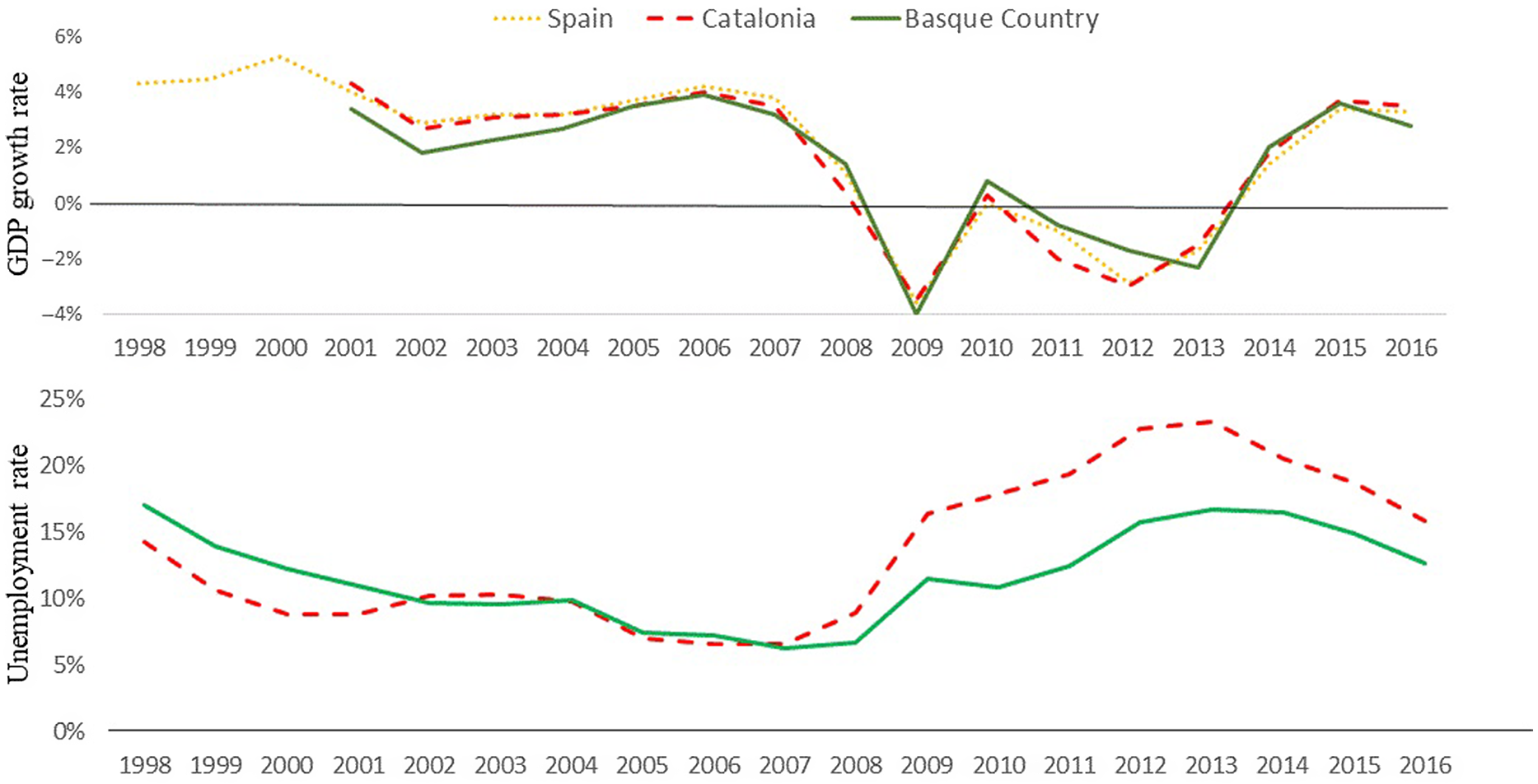

Another interesting variable related to voting decisions and the rise of nationalist votes is the state of the economy. During our period of analysis, two economic crises affected the Basque and Catalan regional economies. The first one encompassed the period 1993–1995, and the second took place in the period 2008–2014, coinciding with the global financial crisis. We show in Figure 2 the GDP growth and unemployment rates from 1998 up to 2016. Notably, pro-independence efforts did not coincide with a scenario of economic crisis, neither in the Basque region nor in Catalonia. In 2001, the Spanish economy was in economic recovery with diminishing unemployment rates in both regions and, similarly, 2015 shows a decreasing unemployment trend. Note how the average growth rate of the Spanish economy is perfectly aligned with the growth of the two regions. In addition to secessionist pressures, the response to the economic crisis could motivate a change in the values that voters assign to different issues. We will discard this possibility since, as we show in our empirical analysis, the perception of the economic situation does not systematically determine vote choices in the years when regional parties pursued independence.

Figure 2. GDP growth and unemployment rates for 1998–2016.

The theoretical model

We use a spatial model of voting. The variables on which we base vote decisions are self-reported responses on the left-right and nationalist positions and self-reported national identity. Our regression model also includes the assessment of the economic situation and population size as control variables.

Consider that there are two positional issues, X and Y, representing the dimensions of the left-right and nationalism and that Z is an identity issue. The positional issues are such that political parties can select and defend particular stands. The identity issue is more of a valence issue attached to the cultural roots of voters. In contrast to standard valence issues, which are assumed to be equal across voters, identity is identical within a group of voters, but different across groups of voters (in line with the models of identity economics by Akerlof and Kranton Reference Akerlof and Kranton2000, Reference Akerlof and Kranton2011 and identity voting by Ansolabehere and Puy, Reference Ansolabehere and Puy2018). For example, voters with Spanish identity may equally evaluate political parties on the identity issue; however, their valuation differs from voters who share a Catalan identity.

Each political party j offers a policy platform in the positional issues, denoted by

![]() $({x_j},{y_j}).$

Each voter i has an ideal policy in the same two positional issues,

$({x_j},{y_j}).$

Each voter i has an ideal policy in the same two positional issues,

![]() $({x_i},{y_i}),$

and possesses a specific identity denoted by

$({x_i},{y_i}),$

and possesses a specific identity denoted by

![]() ${z_i}.$

${z_i}.$

The preferences of voters over political parties are represented by the sum of the negative quadratic distances between the position of the party and their ideal policies on the left-right and nationalist issues, plus the reward (or cost) derived from identity. Let

![]() ${u_i}(j)$

be the utility function representing the preferences of voter i over party

${u_i}(j)$

be the utility function representing the preferences of voter i over party

![]() $j,$

then,

$j,$

then,

where

![]() ${\alpha _i},{\delta _i} \gt 0$

measure the weights or salience assigned by voter i to each unit distance in the left-right and the nationalist dimensions, and

${\alpha _i},{\delta _i} \gt 0$

measure the weights or salience assigned by voter i to each unit distance in the left-right and the nationalist dimensions, and

![]() ${\beta _{ij}}$

measures the weight given by voter i to identity when evaluating party

${\beta _{ij}}$

measures the weight given by voter i to identity when evaluating party

![]() $j.$

Identity can provide a particular reward or cost. If

$j.$

Identity can provide a particular reward or cost. If

![]() ${\beta _{ij}} \gt 0,$

an individual with identity

${\beta _{ij}} \gt 0,$

an individual with identity

![]() ${z_i}$

experiences an extra reward when evaluating party j, meaning that the individual finds party j within the orbit of his/her identity. On the contrary, if

${z_i}$

experiences an extra reward when evaluating party j, meaning that the individual finds party j within the orbit of his/her identity. On the contrary, if

![]() ${\beta _{ij}} \lt 0,$

the individual with identity

${\beta _{ij}} \lt 0,$

the individual with identity

![]() ${z_i}$

evaluates that party j is far from his/her orbit and assigns an extra cost to this party.

${z_i}$

evaluates that party j is far from his/her orbit and assigns an extra cost to this party.

Suppose that a voter compares two parties, j and l. We measure the differential utility of voting j over l which, simplifying yields

where

![]() $\Delta {\beta _i} = {\beta _{ij}} - {\beta _{il}}$

. In this deterministic model, an individual is indifferent between voting j and l when

$\Delta {\beta _i} = {\beta _{ij}} - {\beta _{il}}$

. In this deterministic model, an individual is indifferent between voting j and l when

![]() $\Delta {u_i} = 0,$

he/she votes for j over l when

$\Delta {u_i} = 0,$

he/she votes for j over l when

![]() $\Delta {u_i} \gt 0,$

and he/she votes for l over j when

$\Delta {u_i} \gt 0,$

and he/she votes for l over j when

![]() $\Delta {u_i} \lt 0.$

$\Delta {u_i} \lt 0.$

We transform the proposed deterministic model into a probabilistic multinomial (logit) model. We then estimate what issues are activated both in the Basque and the Catalan regional elections during our period of analysis.

Consider a random variable

![]() $ \mu \in \left( { - \infty\!,\infty } \right)$

that affects voters’ preferences and captures additional motives affecting voting decisions. Let

$ \mu \in \left( { - \infty\!,\infty } \right)$

that affects voters’ preferences and captures additional motives affecting voting decisions. Let

![]() ${\mu _i}$

denote the individual realization of the random variable

${\mu _i}$

denote the individual realization of the random variable

![]() $\mu $

. Hence, if

$\mu $

. Hence, if

![]() $\Delta {u_i} + {\mu _i} \gt 0,$

the individual votes for party

$\Delta {u_i} + {\mu _i} \gt 0,$

the individual votes for party

![]() $j,$

and if

$j,$

and if

![]() $\Delta {u_i} + {\mu _i} \lt 0,$

the individual votes for party l. The probability with which an individual, randomly drawn from the population, votes for party j over party l is measured by the probability

$\Delta {u_i} + {\mu _i} \lt 0,$

the individual votes for party l. The probability with which an individual, randomly drawn from the population, votes for party j over party l is measured by the probability

![]() $Pr(\Delta {u_i} \gt - \mu )$

. Substituting the value of

$Pr(\Delta {u_i} \gt - \mu )$

. Substituting the value of

![]() $\Delta {u_i}$

yields

$\Delta {u_i}$

yields

where

![]() ${k_0} = - {\alpha _i}(x_j^2 - x_l^2) - {\delta _i}(y_j^2 - y_l^2),$

${k_0} = - {\alpha _i}(x_j^2 - x_l^2) - {\delta _i}(y_j^2 - y_l^2),$

![]() ${k_1} = 2{\alpha _i}({x_j} - {x_l}),$

${k_1} = 2{\alpha _i}({x_j} - {x_l}),$

![]() ${k_2} = 2{\delta _i}({y_j} - {y_l})$

and

${k_2} = 2{\delta _i}({y_j} - {y_l})$

and

![]() ${k_3} = \Delta {\beta _i}.$

The dependent variable is a discrete choice between voting for party j or party l, and the parameters of the proposed random utility model can be estimated with a binomial logit regression where

${k_3} = \Delta {\beta _i}.$

The dependent variable is a discrete choice between voting for party j or party l, and the parameters of the proposed random utility model can be estimated with a binomial logit regression where

![]() ${x_i}$

,

${x_i}$

,

![]() ${y_i}$

and

${y_i}$

and

![]() ${z_i}$

are independent variables.

${z_i}$

are independent variables.

There are more than two political parties in the Basque and Catalan elections. Therefore, we use a multinomial logistic model to estimate the probability of voting for party l against every other party (see, e.g. Mc Fadden, 1993).

Footnote 12

We take the PNV in the Basque region and CiU in Catalonia as base parties that are compared to all the others in the multinomial regression (party l in the proposed model). This methodology provides an estimate of the logit coefficients

![]() ${\hat k_0},$

${\hat k_0},$

![]() ${\hat k_1}$

,

${\hat k_1}$

,

![]() ${\hat k_2},$

and

${\hat k_2},$

and

![]() ${\hat k_3}$

that we use to measure the average salience of each issue dimension in voters’ preferences,

${\hat k_3}$

that we use to measure the average salience of each issue dimension in voters’ preferences,

![]() $\alpha $

and

$\alpha $

and

![]() $\delta $

, through the formulas

$\delta $

, through the formulas

We can also evaluate the average effect of identity on voting decisions through the formula

![]() $\Delta \beta = {\hat k_3},$

where the estimated value

$\Delta \beta = {\hat k_3},$

where the estimated value

![]() ${\hat k_3}$

indicates the average concern for voters of each unit of identity in each election year. In addition, we control for two other variables, individual’s assessment about the economic situation and population size. In sum, the proposed model evaluates which of the following four factors impact voting decisions:

${\hat k_3}$

indicates the average concern for voters of each unit of identity in each election year. In addition, we control for two other variables, individual’s assessment about the economic situation and population size. In sum, the proposed model evaluates which of the following four factors impact voting decisions:

-

Positional voting, which measures how voters opt for parties closer to their ideal positional issues. In this respect, we assess the impact of the left-right and the nationalist dimensions.

-

Identity voting, which is tied to the culture and the feelings for the territory. It captures how voters move toward those parties that align with their identity (see Sorens, Reference Sorens2005; Ansolabehere and Puy, Reference Ansolabehere and Puy2016).

-

Instrumental voting, which captures how voters care about the policy they get (see Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1976). We explore whether perceptions about the economic situation in the region have an impact on voting decisions.

-

Community size, which captures geographical divides, a variable correlated with regional party vote (Beck, Reference Beck2000; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2020).

The following section measures the relevance of these factors in voters’ preferences during a period where regionally based parties alternated their strategy between integration and separatism.

The empirical model

We follow an empirical strategy in two steps. First, we estimate the logit coefficients and evaluate which explanatory variables have an impact on voting decisions. Second, we calculate the estimates that measure the average relevance of each issue dimension when voting along our period of analysis.

The pre- and post-electoral CIS’s surveys to the Basque and Catalan Elections ask respondents whether they voted and how. We join each election year’s pre- and post-electoral responses and focus on three self-interest variables – left-right orientation, nationalist orientation, and assessment of the economy- and two group-identity variables – national identity and population size. The online Appendix C describes our data set specifying the variables contained in each pre- and post-electoral survey, as well as summary statistics. Footnote 13

The left-right and nationalist orientation of each voter is captured by self-reported positions in the 1 to 10 point scales.

A survey question measures national identities and reads as follows: ‘Which of the following answers better identifies you?: (1) I feel only Spanish; (2) I feel more Spanish than Basque (or Catalan); (3) I feel equally Spanish and Basque (or Catalan); (4) I feel more Basque (or more Catalan) than Spanish; (5) I feel only Basque (or only Catalan)’. In this question, voters associate themselves to a particular identity group. We interpret that this question reflects the cultural roots of each respondent. There exist a link between national identity and language usage, Euskera in the Basque Country and Catalan in Catalonia. Footnote 14 The language questions, whether interviewed speak Euskera and Catalan, can also capture identity. This question, however, is only present in half of the surveys. We use the language question to perform a robustness analysis.

Regarding the assessment of the economy, since 1998 for the Basque region and 2006 for Catalonia, the CIS’s surveys ask the same question: ‘What is your perception about your region’s economic situation?: (1) Very good; (2) Good; (3) Regular; (4) Bad; (5) Very bad’. Footnote 15 We use this question to evaluate the effect of economic discontent.

Finally, population size is described in three categories numbered from 1 to 3, where (1) means rural areas with less than 10,000 inhabitants; (2) means cities with a number of inhabitants between 10,000 and 100,000; and (3) includes the remaining larger cities.

Vote choice or preference is the outcome of interest or dependent variable. The surveys branch the voting question, asking people whether they voted (or planned to vote). Of voters (or likely voters), the survey asks for which party or coalition of parties the individual voted.

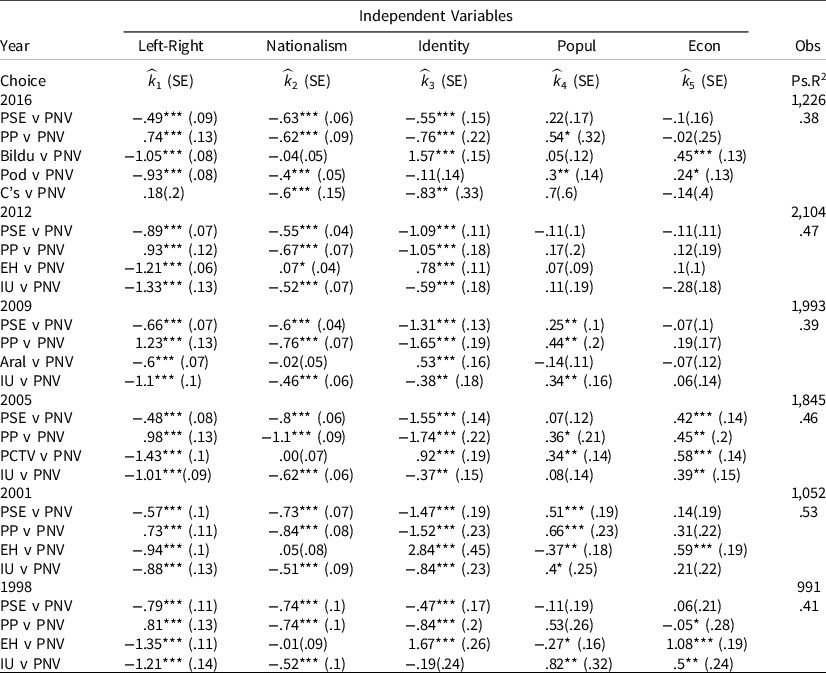

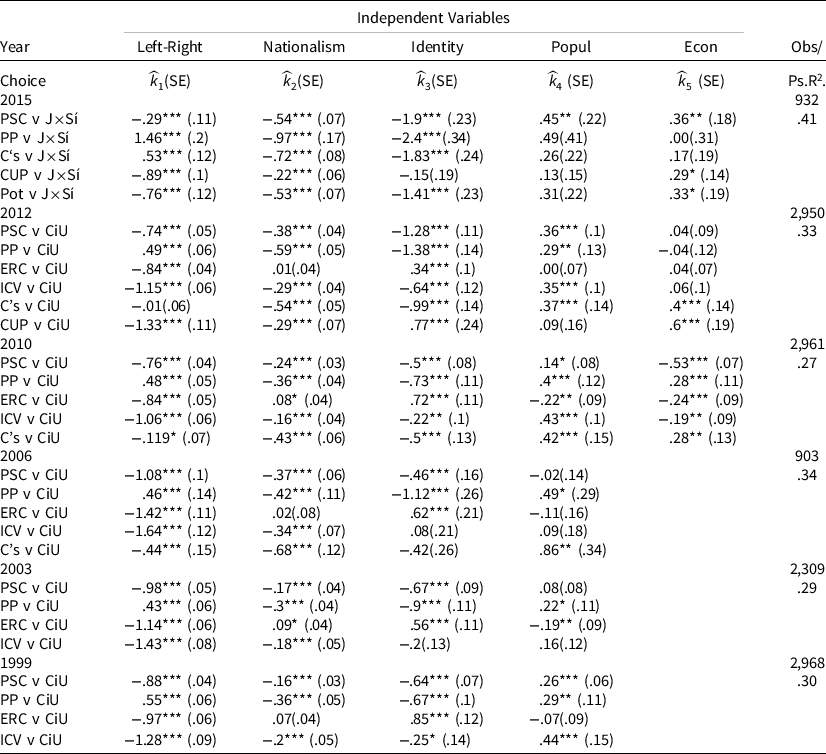

Next, we compare the multinomial regression coefficients that explain vote choice in the Basque Country and Catalonia. Footnote 16 Our analysis covers six consecutive elections in each region, which provides a comprehensive comparative analysis. The following Tables 1 and 2 describe the estimated coefficients when the PNV and CiU are base parties. In the 2015 Catalan election, CiU and ERC joined in a coalition denominated J×Sí. We take such coalition as base party in this election year.

Table 1. Explaining vote for party, multinomial logit. Basque Country 1998–2016

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses *** p< 0.01, ** p< 0.05, * p< 0.1.

Table 2. Explaining vote for party, multinomial logit. Catalonia 1999–2015

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses *** p< 0.01, ** p< 0.05, * p< 0.1.

Interestingly, regression results reveal that positional and identity issues are the driving forces determining vote decisions, both in the Basque and Catalan regions. Population size and the economic assessment do not exert systematic effects on voting patterns. Several comments are in order:

First, we find evidence of positional voting. Voters self-located to the right are less likely to vote for left-wing parties (PSE, PSC, Podemos, and other minor left-wing parties) against PNV or CiU but more likely to vote for PP and C’s, and the opposite holds for respondents self-located to the left. In the nationalist dimension, more nationalist self-declared respondents are less likely to vote for non-nationalist parties against PNV, CiU, and J×Sí, and the opposite holds for less-nationalist self-located respondents. In the comparisons Bildu v PNV, EH v PNV, or ERC v CiU, the estimated coefficients of self-located nationalist positions are very low. It occurs because the nationalist parties, PNV and CiU, and the most extreme left-nationalist parties, EH and ERC, hold an almost indistinguishable nationalist position. A similar effect is produced between CUP v CiU in the 2012 election.

Second, regarding national identity, we observe how the sign is negative in most of the comparisons. We interpret that, on average, regional identity, Basque or Catalan, implies a higher probability of voting for the dominant party in the regions, PNV and CiU (or J×Sí in 2015), against other options. Less intense regional identity decreases the probability of voting for the PNV and CiU against other parties. Only in those comparisons between the dominant party and the most extreme left-nationalist parties in the regions Bildu/EH/Aralar/PCTV in the Basque region and ERC in Catalonia, we find that, on average, the coefficients are positive. Thus, we find the opposite effect to the one explained above. In the Basque Country, the identity variable is the one that captures the heterogeneity among nationalist parties (see the high identity coefficient in the comparisons Bildu v PNV or EH v PNV). We can interpret that for the Basque region, the stronger the Basque identity (with respect to the weaker), the more likely (the less likely) it is for voters to opt for EH/Bildu compared to PNV. Footnote 17 Due to the high correlation (about .6 tau-c value on a range of plus one minus one) between nationalist self-positions and identity, we expected that these two variables could not simultaneously have a significant effect on vote patterns. Both variables, however, explain vote choices and capture different voting incentives.

Third, the assessment of the economy has an unstable impact on voting decisions. Higher values of the economy variable indicate a more negative perception of the regional economy. In the Basque Country and for the 2005 electoral year, a positive economic perception increased the probability of voting for the PNV against every other party. This effect can be interpreted as retrospective voting since the PNV held office just before the 2005 election. In Catalonia, the regression reveals that in the 2010 election, the economic recession exerted a negative impact over the PSC, ERC, and ICV, but a positive effect over CiU and PP. Thus, the recession punished the left-wing parties among which the incumbent party, the PSC, lost the Catalan presidency. The economic recovery in the 2015 and 2016 elections benefited the two dominant incumbent nationalist parties, J×Sí and PNV, over PSC, CUP, and Podemos in Catalonia and Bildu in the Basque Country.

Finally, there is no systematic effect of population size on voting probabilities for the Basque Country. The 2001 election is an exception where respondents living in large cities, in contrast to small ones or the rural area, showed a higher likelihood of voting for one of the two nationwide parties, PSE and PP, against the dominant nationalist party, the PNV. Catalonia exhibited a similar pattern in 2010, 2012, and especially in the 2015 elections, when the largest the city size of the respondent, the higher the probability of voting for the Socialist Party against CiU. We also find that respondents of small cities or rural areas compared to large cities showed a higher likelihood of voting for more extreme nationalist parties (EH and ERC) against the PNV or CiU. Footnote 18 It is noteworthy, that territorial divisions activated in the two regions in those elections that confronted constitutionalist and independentist. Territorial divisions are associated with economic activity and old cultural histories. In line with Colantone and Stanig (Reference Colantone and Stanig2018), we interpret that individuals living in large cities are more affected by the economic consequences of forming a newly independent nation when compared to rural areas. Besides, citizens in large cities are generally less attached to regional culture.

Measuring issue-salience

Our strategy to evaluate the effect of secessionist pressures on vote decisions consists of identifying equivalent changes in the estimated regression coefficients corresponding to the 2001 Basque election and the 2015 Catalan election. We use Catalonia as a control group to assert the validity of Basque separatist efforts in 2001, and the Basque Country as a control group when analyzing the impact of secessionist pressures in Catalonia in 2015. The proposed comparison between the two regions shows relevant implications:

First, in the 2001 Basque election and the 2015 Catalan election, the perception about the economic situation does not exert a systematic impact. When comparing the two largest nationalist parties, respondents with a positive perception about the economic situation are more likely to opt for the incumbent, the PNV, and J×Sí. In contrast, those with a negative perception show a higher probability of voting for EH or CUP. This effect, however, is not particular to those election years when nationalist parties put secession to the vote. Indeed, this effect is persistent and of equivalent magnitude in the Basque Country for most election years.

Second, for the 2001 Basque and 2015 Catalan Elections, respondents living in big cities show a higher probability of voting for the most significant nationwide party in the region, the socialists PSE and PSC, against the dominant nationalist party, the PNV and J×Sí. On the contrary, respondents living in rural areas are more likely to opt for the dominant nationalist parties. The geographical location, we observe, matters in times of secessionist pressures. When taking Catalonia as a control group to check the internal validity of the population effect on the 2001 Basque elections, we observe that population size has no impact on vote decisions among the two largest parties in Catalonia for the 2003 election and half the impact for the 1999 Catalan election. Likewise, taking the Basque Country as a control group to validate the population effect on the 2015 Catalan elections, we find that population size has no statistically significant impact on voting decisions for the 2012 and 2016 Basque elections. The comparative suggests that territorial divisions activate as a predictor of vote choice in times of secessionist tensions.

Third, there are three-issue dimensions that, in the two regions, have a persistent effect on voting decisions, namely, identity and the two positional left-right and nationalist issues. We evaluate their magnitude and impact over time. The spatial model of vote choice provides a formula to calculate the salience of the two positional issues, the left-right and the nationalist dimension, in voters’ preferences. The salience of each positional issue is measured by the average increment in marginal utility obtained by voters when the distance between their own ideal policy and the party policy reduces in a unit. The salience of each positional issue is deduced through the expressions in (4). We first compare which issue dimension, left-right or nationalism, matters more to the voters. Separated from the positional issues, we secondly evaluate how the estimated coefficient that assesses the relevance of national identity has varied over time.

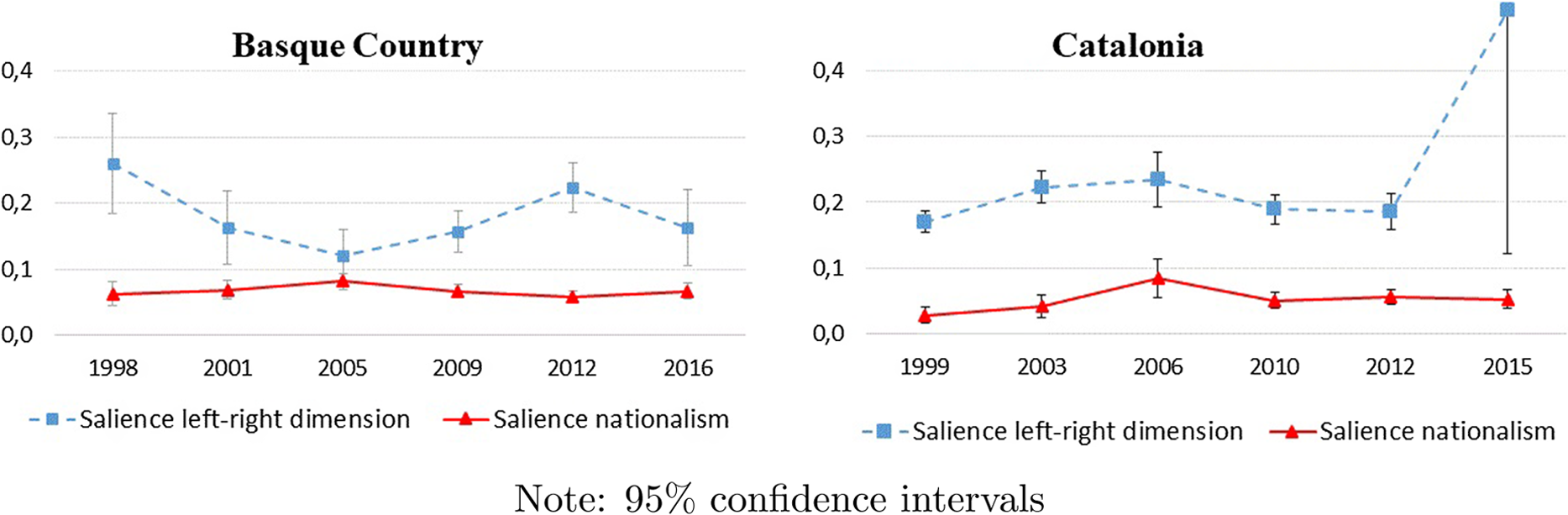

For each region and each election year, we plot the estimated salience of each positional issue together with its confidence interval across every comparison between the Socialist Party (PSE in the Basque region and PSC in Catalonia) and the dominant nationalist parties in these regions (PNV and CiU). Figure 3 summarizes the obtained estimates. Footnote 19

Figure 3. Estimated saliences of the left-right and nationalist dimensions.

We observe that, in both regions and every election year, the left-right issue compared to nationalism is more relevant. In Catalonia, the salience of the left-right issue is slightly higher than in the Basque Country. Unexpectedly, and for the last considered election, the left-right salience in Catalonia experiences a relevant but ambiguous shift (due to the wide confidence interval). We attribute this shift to the emergence of the J×Sí coalition that joined two opposing factions in the left-right dimension, ERC and CiU. Apart from this shift, neither the nationalist nor the left-right dimensions capture any relevant movement along the analyzed years, not even when elections were more strident about separatism.

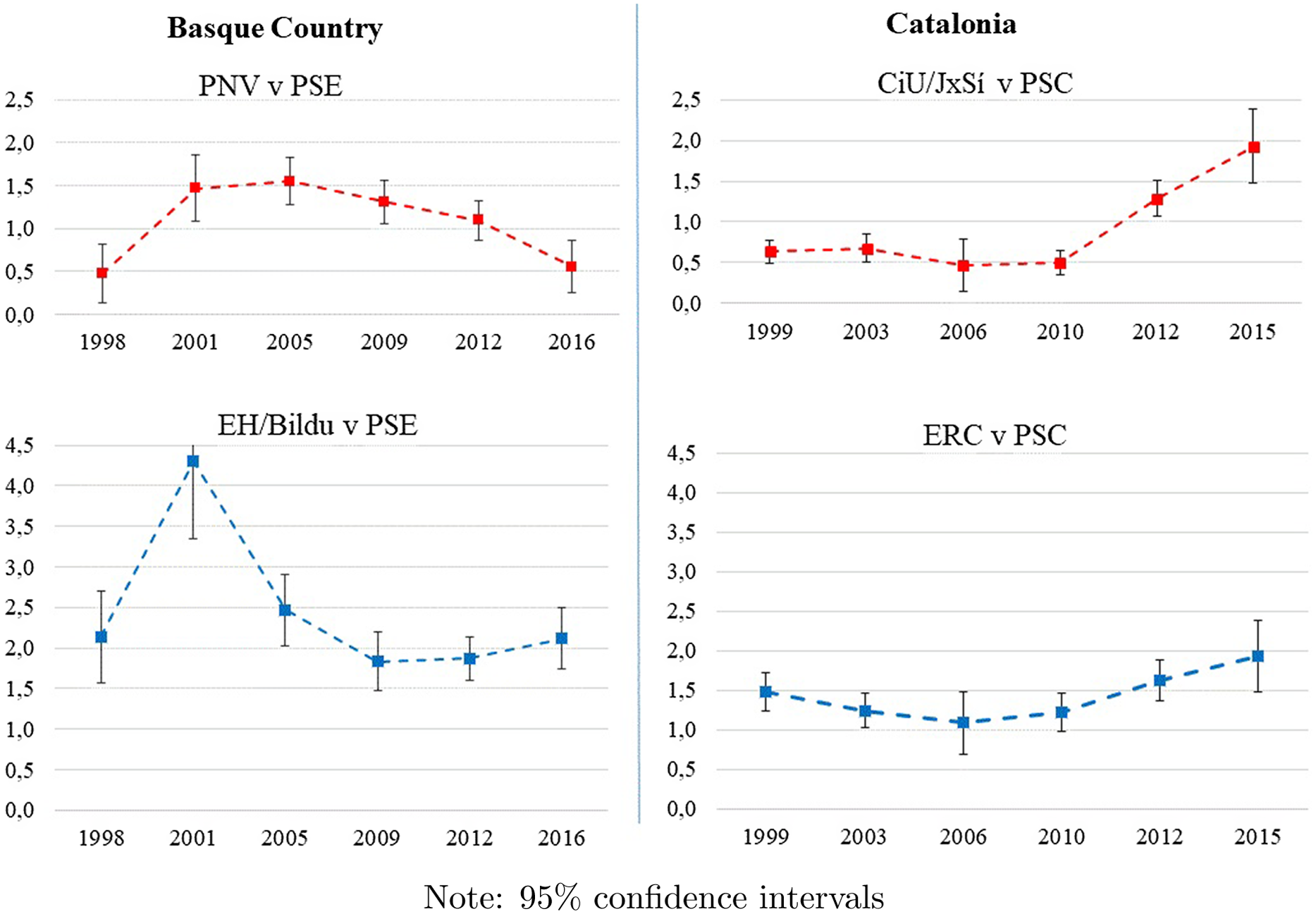

We next compare how the national identity coefficients have changed over time. National identity can be interpreted as a valence attribute of a political party concerning its identification with a national sentiment. The identity coefficients capture the average reward that voters assign when evaluating those political parties that share one’s identity. Footnote 20 For example, a positive value in the identity coefficient for the comparison between Bildu and PSE measures the extra reward (or utility) when voting for Bildu over PSE associated with Basque identity voters. Thus, the higher the identity coefficient, the more relevant is the identity variable over other variables that explain vote choice.

The regression analysis in Tables 1 and 2 select PNV and CiU as base parties. We estimate similar multinomial logistic regressions with the socialist parties (the PSE in the Basque region and the PSC in Catalonia) as base parties. It permits vote choice comparisons between the pro-independentist parties and the socialists. We plot in Figure 4 the value of the identity coefficients over the analyzed period and compare the results for the two regions. Despite the common political and cultural characteristics of the Basque Country and Catalonia, the plots exhibit different tendencies. Figure 4 reflects our most interesting result:

Figure 4. Estimated salience of national identities.

First, the comparison between the Basque region and Catalonia shows opposite paths; the low relevance of identity in Catalonia up to 2010 contrasts with the up to 2005 high relevance of identity in the Basque region. The EH v PSE and the PNV v PSE comparisons reflect the strong salience of identity in the 2001 Basque Elections and its decreasing impact afterward. In Catalonia, however, the ERC v PSC and the CiU v PSC comparisons reflect an increasing salience of identity that finds its maximum in the 2015 Catalan election when CiU and ERC formed the J×Sí coalition. Consider the 1998–2003 period. We observe how the relevance of identity is on the rise in the Basque Country, but, for the same period, there is no relevant shift in the identity coefficients in Catalonia. By contrast, for the period 2010–2016, and the comparisons among the largest parties, the PNV v PSE or CiU v PSC, we find opposed tendencies; the Basque Country, unexposed to secessionist pressures in this period, shows a decreasing path, while we observe a rise of the relevance of identity in Catalonia.

Second, identity has been a less relevant variable to explain vote decisions in Catalonia. Traditionally, the Catalan Socialist Party (PSC) has been close to the Catalan identity compared to the PSE in Euskadi (Serrano, Reference Serrano2013). We deduce that, generally, identity has been a more relevant issue in the Basque region, although differences vanish when comparing the 2015 Catalan and 2016 Basque elections. The online Appendix F calculates estimated probabilities of voting for the dominant parties in the regions as a function of identity. We show the deep division produced by identity in the 2001 Basque and 2015 Catalan elections.

Finally, as a robustness check to our previous result, we analyze whether the language variable, which indicates whether the interviewed speaks Euskera or Catalan, exerts a similar effect on vote decisions in these two regions. We substitute the identity variable by language in the previous regression analysis and estimate the impact of language as an issue dimension in the probability of voting for the two largest parties in the regions. In the online Appendix G, we describe the resulting coefficients for the comparisons between PSE v PNV and PSC v CiU. Due to the lack of language questions in the Basque surveys previous to 2005, comparisons run over four election years. Interestingly, starting in 2005, the impact of language follows an increasing effect on Catalonia. By contrast, the influence of Euskera-speaking over vote decisions in the Basque Country is diminishing for the same period. This finding corroborates our hypothesis, namely that the identity associated with the culture and the language of the territory activates when regionally based parties pursue secession and deactivates when leaving aside the secessionist goal.

Conclusion

This paper aims to find evidence of human response to those emotions associated with the possibility of forming a new nation. We explore how salience, understood as the relative importance that an actor ascribes to a given issue in the political agenda, varies in times of secessionist pressures. Issue-salience manifests in electoral choices, and we use vote decisions to evaluate the weights that, on average, voters assign to self-interest versus social-identity issues.

Two regions with similar histories and political systems, the Catalans moved to leave Spain in the second decade of the 2000s, yet, the Basques pursued independence in the early 2000s and stopped afterward. Our comparative strategy exploits that separatist efforts in these regions did not coincide in time.

When secession is put to the vote, we find that two dividing lines emerge and display their potential to determine voting decisions. National sentiments and community size define these new lines. Our analysis suggests that material self-interests dilute when the political agenda focuses on separatism. The left-right and nationalist positions of the voters reflect self-interests associated with taxation, public expenditure, or regional autonomy. We show that the average importance of these issues diminishes in favor of other relatively fixed factors related to group identities, such as national sentiment and territorial roots. The determinants of voting become more social and less material. Besides, secessionist tensions did not emerge in the midst of economic crises, and we cannot attribute the rise of group-identity issues to economic factors.

The Catalan and Basque comparison provides an instructive case and adds new evidence on the importance of identity politics and territorial divisions in shaping modern nations. What has occurred in Catalonia and the Basque region is a rising cultural division, not increased ideological polarization or economic discontent. Even when the underlying secessionist motivation may be associated with economic interests (Hierro and Queralt, Reference Hierro and Queralt2021), our evidence demonstrates that when voters are on the brink of separatism, they turn to their national identity and territorial roots.

A key question is the external validity of our empirical results for other countries such as Italy, the UK, or Canada, where pro-independentist regional forces coexist with others that defend integration into the nation (List, Reference List2020). And more generally, we could explore which other elections can potentially coordinate our emotional systems changing the relevance that we assign to self-interest versus group-identity issues. These are open questions that we leave for further research. Importantly, however, our proposed theoretical framework adapts to every multidimensional electoral competition context and can be used to test voters’ responses to actual events.

In our analysis, voters’ decisions depend on parties’ positions, which are treated as given. We do not address the question of why parties take these positions. Footnote 21 In this respect, we follow the empirical literature by Schofield (Reference Schofield2004), Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Merrill, Simas and Stone2011), or Mauerer (Reference Mauerer2020). Recent contributions provide evidence of political parties’ response to voters’ priorities when deciding which policy issues to emphasize (Spoon and Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2014; Stimson, Reference Stimson2015; Klüver and Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2016). Footnote 22 We do not address this causality but instead provide evidence on how issue-salience measured in voters’ preferences respond to national dissolution. Whether voters or political events fired the secessionist strategy is a relevant question that we leave for further research.

Our analysis reveals that our emotions and values respond to political events and reflect in vote decisions. Actual discontents or the threat of national dissolution activate our cultural and territorial values to the detriment of other self-interests that usually drive the political agenda. Old cultures become roots for contemporary electoral results.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000261.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Bernard Grofman, Elona Harka, Ingrid Mauerer, Thomas Meyer, Ignacio Ortuño-Ortín and the seminar audience of University of Mannheim, Universidad de Málaga and the ECPR General Conference for helpful comments and suggestions. The authors acknowledges excellent research assistance by Jorge Antonio Gómez Fábrega y María Daysi Orna Bravo. Finally, Socorro Puy acknowledges financial support under the projects PID2020-114309GB-I00 (from Gobierno de España) and PY18−2933 (from Junta de Andalucía)