Reissues have been a cornerstone of the music industry for decades. K-Tel Records’ 25 Country Hits, a cheaply made and heavily marketed compilation album released in 1966, first demonstrated that reissues could be profitable.Footnote 1 Interest in reissues expanded considerably in the 1980s. This boom was partly due to the rise of compact discs, replacing vinyl LPs, and the ensuing reissuing of albums on CD. However reissues also led to new compilations and sets, led especially by Rhino Records, an independent record company that made its name by reissuing and repackaging older records as new compilations. Rhino won critical praise for their attention to fidelity, finding high-quality masters to reproduce, and for their visually attractive packaging.Footnote 2

Unlike repressings of vinyl LPs, reissues often involve new creative work: Remastering and changing the format, assembling compilations, updating liner notes, or including new bonus tracks. Soon after the compact disc format emerged, reissues began to include deluxe retrospectives of artists, including Bob Dylan's Biograph in 1985 and the hugely successful Eric Clapton Crossroads four-disc set in 1988. These reissues offered connoisseurs rare, demo, and unreleased tracks as well as lavish packaging. Today, reissues maintain an active role in the music industry, from compilations like the multiplatinum Now That's What I Call Music series to the multitude of box sets and anniversary reissues of canonic albums. Critics now regularly issue best-of-the-year lists celebrating the most elaborate box sets and reissues; 2019's reissues, for example, included a fiftieth Anniversary Deluxe edition of The Beatles’ Abbey Road, featuring twenty-three outtakes and demos, The Bakersfield Sound, 1940–1974, a collection of over 200 tracks with a 225-page booklet, and Kate Bush: The Other Sides, consisting entirely of unreleased recordings from the artist.

Although these reissues frequently gain attention in the popular press, scholars have largely ignored reissues as a subject, even as popular music scholarship has widened its perspective to consider the impact of figures beyond the original artist. In his review of Albin J. Zak's The Poetics of Rock: Cutting Tracks, Making Records, Robert Walser writes approvingly that Zak “shifts our attention from the music's most marketable figures—performers and songwriters—to the people who actually create the ‘musical works wrought in sound,’” namely producers, engineers, mixers, and technological inventors.Footnote 3 Zak's book effectively shows the complexity of the collaborations behind recordings and argues that lesser-known figures have been just as influential in music history. Scholars have also documented how artists and fans use songs to create new meanings, whether through transformative cover versions, as George Plasketes, Alyssa Woods, and others have discussed,Footnote 4 or through listener-generated mash-ups, which Aram Sinnreich and Kembrew McLeod argue can have a subversive, political potential.Footnote 5 Reissues differ from the above techniques in that they do not generate new sounds, but simply reproduce existing recordings. Nevertheless, like producers and engineers, reissuers assist in the manufacturing of a new commercial recording, and their artistic vision can be clearly felt in the final product. Like mash-ups and covers, reissues can juxtapose sounds and styles in meaningful ways. In doing so, they can be equally transformative of the way we listen to and interpret songs.

To better understand the activity of reissuers, this essay draws from museum studies scholarship to consider reissuers’ work as akin to that of a museum curator. Like museums, reissues frequently center on historical recordings as important artifacts—a sort of aural exhibition. Moreover, many deluxe box sets emphasize the physical material—notes, photographs, and elaborate designs—as much as the musical content. In his study of critical editions of American music, Mark Clague makes a similar move, comparing critical editions to portraits, suggesting that “musical notation communicates on several levels.”Footnote 6 Clague analyzes the iconographic details of notation, cover art, and supplemental images, as well as the editorial decisions concerning what images, text, and music to include and how to notate and edit them. Reissues offer a similar wealth of material to analyze, from editorial (or curatorial) choices and selections to visual iconography.

My essay examines in depth one important reissue, Harry Smith's The Anthology of American Folk Music, a collection of eighty-four commercial recordings made between 1926 and 1932, compiled by Smith from his extensive record collection into a three double-LP volume set, and released by Folkways Records in 1954. Now considered a canonic work of Americana, no less than “a bedrock of our national musical identity” according to Rolling Stone's David Fricke, it has garnered critical praise, robust scholarly attention, and even an Honorary Grammy Award for Smith.Footnote 7 Much of this attention came in the 1990s, when another key development in the Anthology's legacy occurred: A widely praised reissue of the album on compact disc by the Smithsonian in 1997. In the years since the reissue, scholars have examined the album as a refraction of the political environment of the 1950s.Footnote 8 Little attention has been given, however, to its status as a reissue—a fact taken for granted by many listeners. Examining the Anthology from this angle not only allows us to reconsider previous readings of the Anthology anew, but also illuminates the seldom-considered interpretive work done through the act of reissuing.

In her book Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett argues that exhibitions “are also exhibits of those who make them.”Footnote 9 The Anthology was similarly the product of distinct choices that reflect the values of its reissuers. First I consider how Harry Smith's agency as reissuer sought to define folk music in specific ways, accomplished through the collection, selection, and sequencing of the tracks, as well as his annotation through liner notes. These choices diverged from the methods and ideologies of other collectors. I then turn to the Smithsonian's agency as reissuer of the Anthology on compact disc. Their work included remastering tracks, reproducing liner notes, and compiling accompanimental material for a lavish box set. Much of the production of this reissue is documented in the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, allowing an unusually detailed glimpse into the act of reissuing. That documentation affords a glimpse into the choices made at various steps, reflecting the Smithsonian staff's mission and values as curators of American history. Considering both Smith and the Smithsonian in tandem as agents repackaging older material demonstrates how museological practices of preservation, collection, and curation continually reshaped the meaning of this music as an aesthetic and political object.

Smith's Decisions: Collecting and Curating the Anthology

Harry Smith's work as creator of the Anthology of American Folk Music began, as museum collections do, with the act of collecting. Scholars have begun to explore record collecting as a cultural activity. In Wax Trash and Vinyl Treasures: Record Collecting as a Social Practice, Roy Shuker offers a compelling ethnographic overview of these activities, examining how and why collectors pursue this hobby. Of particular importance to Smith's collecting, Shuker details how collectors are driven both by an interest in nostalgia and history and by personal aesthetics in their collecting, and how collectors in turn shape the economics of the music industry and help construct canons by instilling value upon certain artists.Footnote 10 These perspectives resonate with how museum scholars have theorized collecting. Ivan Karp finds that the act of collecting is “intimately tied to ideas about art, science, taste, and heritage. Hence [it is] bound up with assertions about what is central or peripheral, valued or useless, known or to be discovered, essential to identity or marginal.”Footnote 11 This aspect of articulating social and cultural values was especially borne out in the early work of music collectors.

Heritage and cultural values have long shaped music collection in the twentieth century. As early as 1899, folk music collecting promoted white rural culture as a form of racial purity. William Goodell Frost noted that rural whites played the role of “living ancestors” particularly because of their lack of contact with African Americans; John Fox Jr. would similarly praise their patriotism in contrast with that of immigrants, African Americans, and Native Americans 2 years later.Footnote 12 Cecil Sharp, one of the most prominent collectors of Anglo-American folk culture, deemed that the folk singers he encountered in the United States had “one and all entered at birth into the full enjoyment of their racial heritage.”Footnote 13 At the same time, African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance similarly turned to Black musics as a source of racial pride, and considered their own musical traditions as a folk culture. W. C. Handy and James Weldon Johnson both sought to position blues and ragtime respectively as folk, rather than commercial, music.Footnote 14 Nevertheless such attitudes of racial purity were mythologized; the reality of folk performance featured a freer interchange of music across racial lines. Historian Karl Hagstrom Miller notes that Black Americans enjoyed square dance tunes, while white Americans enjoyed the blues just as much as the more stereotypical converse.Footnote 15

Intricately entwined with folk collectors’ emphasis on racial heritage and purity was a rejection of the commercial. The early twentieth century saw not only a rise in immigration, but also a rise in urbanization, as rural Americans migrated to urban centers, drawn by job opportunities from booming industrialization. Folk collectors and anthropologists like Cecil Sharp, Jean Toomer, and Zora Neale Hurston all were suspicious of industrialism's corruptive power and the threat of cultural elimination it posed, and saw folk music collection as a safeguard for cultural heritage.Footnote 16 In his own collection of cowboy songs, John Lomax rejected traditional songs that sounded too redolent of popular music, while also including newly written songs that fit his preconception of traditional-sounding music but excising the authors to maintain the illusion of their timelessness.Footnote 17 Although commercial producers of folk music—the same producers who made the recordings Harry Smith used—did not share this suspicion, they nevertheless sought to capitalize on folk music's novelty by making it distinct from Tin Pan Alley songs. Record scouts would censor repertoire and shape the sound to conform to expectations on the basis that they already had better ensembles performing contemporary hits.Footnote 18 Likewise, Jeff Todd Titon suggests, performers might self-censor themselves based on their own perceptions of what record companies might want to hear.Footnote 19 As with race, Karl Hagstrom Miller refutes the idea that folk artists shunned the commercial, detailing how both Black and white artists performed popular Tin Pan Alley music of the day.Footnote 20

A generation later, record collecting emerged in the 1940s and 1950s as a subcultural discourse that was shaped by the same values of racial purity and anti-commercialism. In this instance, however, collectors were predominantly white, Ivy League-educated fans of jazz and blues. Smith's contemporaries—Charles Edward Smith, Charles Frederick Ramsey Jr., Samuel Charters, and James McKune, among others—collected and traded records, debated their merits, and eventually reissued historic jazz and blues recordings and published books on the subjects. Their output remains problematic, however. Although their intentions to shed light on important and influential Black musicians who had been unfairly eclipsed by more popular and successful white artists were laudable, they nevertheless trafficked in and perpetuated essentializing myths. Historian Marybeth Hamilton has examined how collecting strategies were “shaped by mythologies of race… the venerable vision of a pure and uncorrupted black voice,” whereas critic John Dougan has suggested that romanticizing poverty was “guided by the collectors’ bohemian refusal of what they saw as the egregious commerciality of rock and roll, an aesthetic distinction which allowed them to wed the collecting of obscure vernacular music with their anti-consumerist ethics.”Footnote 21

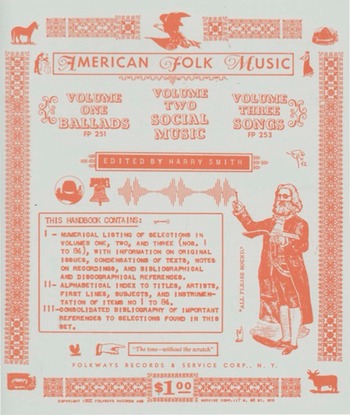

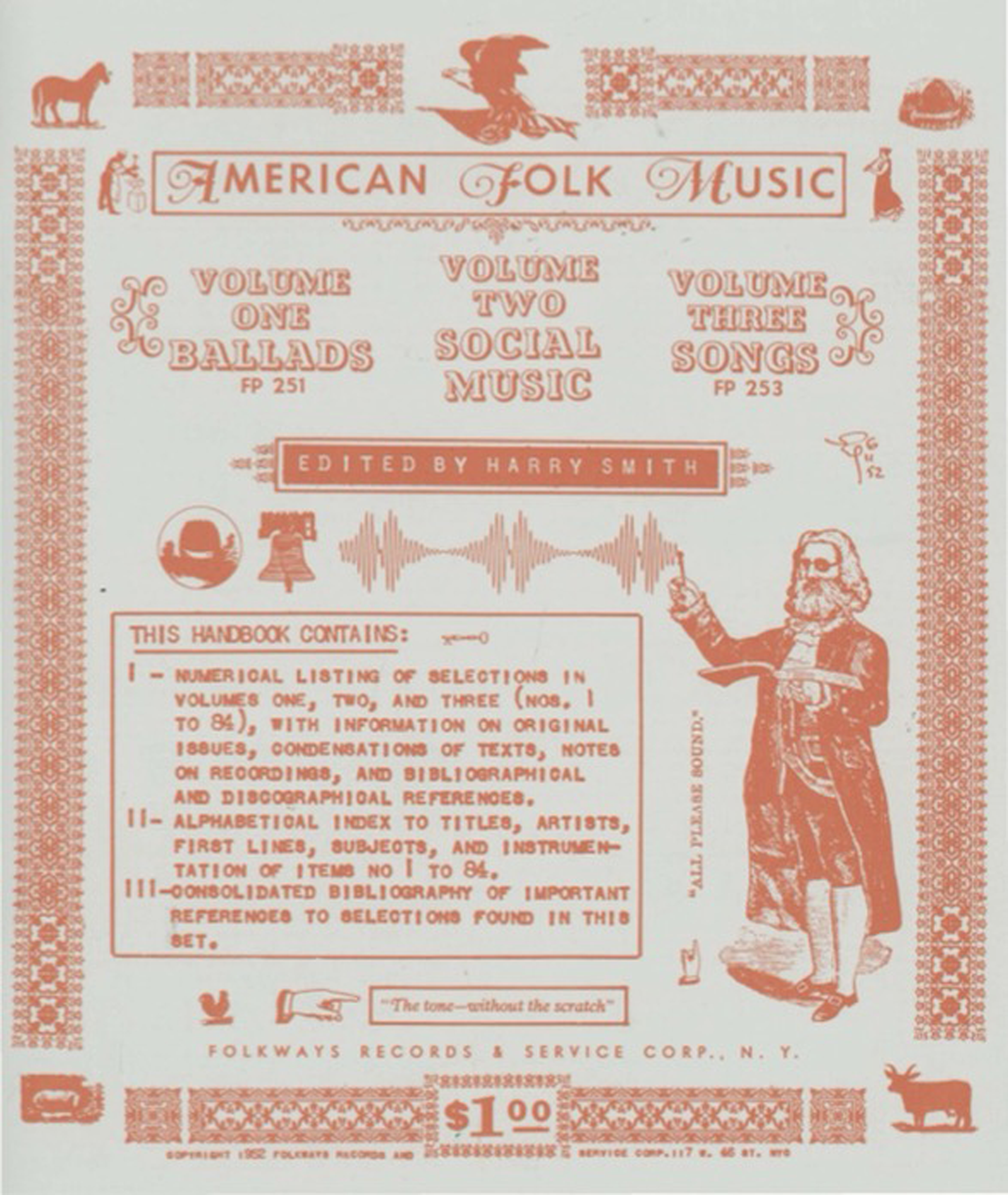

This was the world in which Harry Smith traveled, and he corresponded with many other prominent collectors of the time. Nevertheless, Smith differed from them, rejecting the mythology of racial purity and the idealization of the non-commercial. He did this through his roles as curator of the Anthology—first, by collecting and selecting tracks; second, by his sequencing of his selections, akin to the curation of a display, laying out each artifact in a narrative sequence; and third, by his labeling of artifacts, seen in his elaborate liner notes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cover page to Harry Smith's liner notes for Anthology of American Folk Music. Printed with permission from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Smith breaks down racial segregation in the Anthology, mixing tracks and deliberately obscuring racial lines: White as well as Black artists play the blues; a white and a Black artist each sing about John Henry; and Furry Lewis, a Black artist, performs a white-associated ballad about Casey Jones.Footnote 22 In an interview, Smith directly critiqued the practices of record collectors he saw as continuing this segregated practice through their emphasis on racial purity:

Before the Anthology there had been a tendency in which records were lumped into blues catalogs or hillbilly catalogs, and everybody was having blindfold tests to prove they could tell which was which. That's why there's no such indications of that sort (color/racial) in the albums. I wanted to see how well certain jazz critics did on the blindfold test. They all did horribly. It took years before anybody discovered that Mississippi John Hurt wasn't a hillbilly.Footnote 23

Although recordings were sold in a strictly segregated fashion, as “hillbilly” and “race records,” Smith never used race as a means of organizing and sequencing the tracks. Indeed, his liner notes squarely denounce the practice. In the foreword, he remarks, “Unfortunately these unpleasant terms are still used by some manufacturers,” and in the bibliography, he reproduces several catalog images of race records, stating, “The advertising of these envelopes gives a good idea of the companies [sic] attitude toward their artists.”Footnote 24

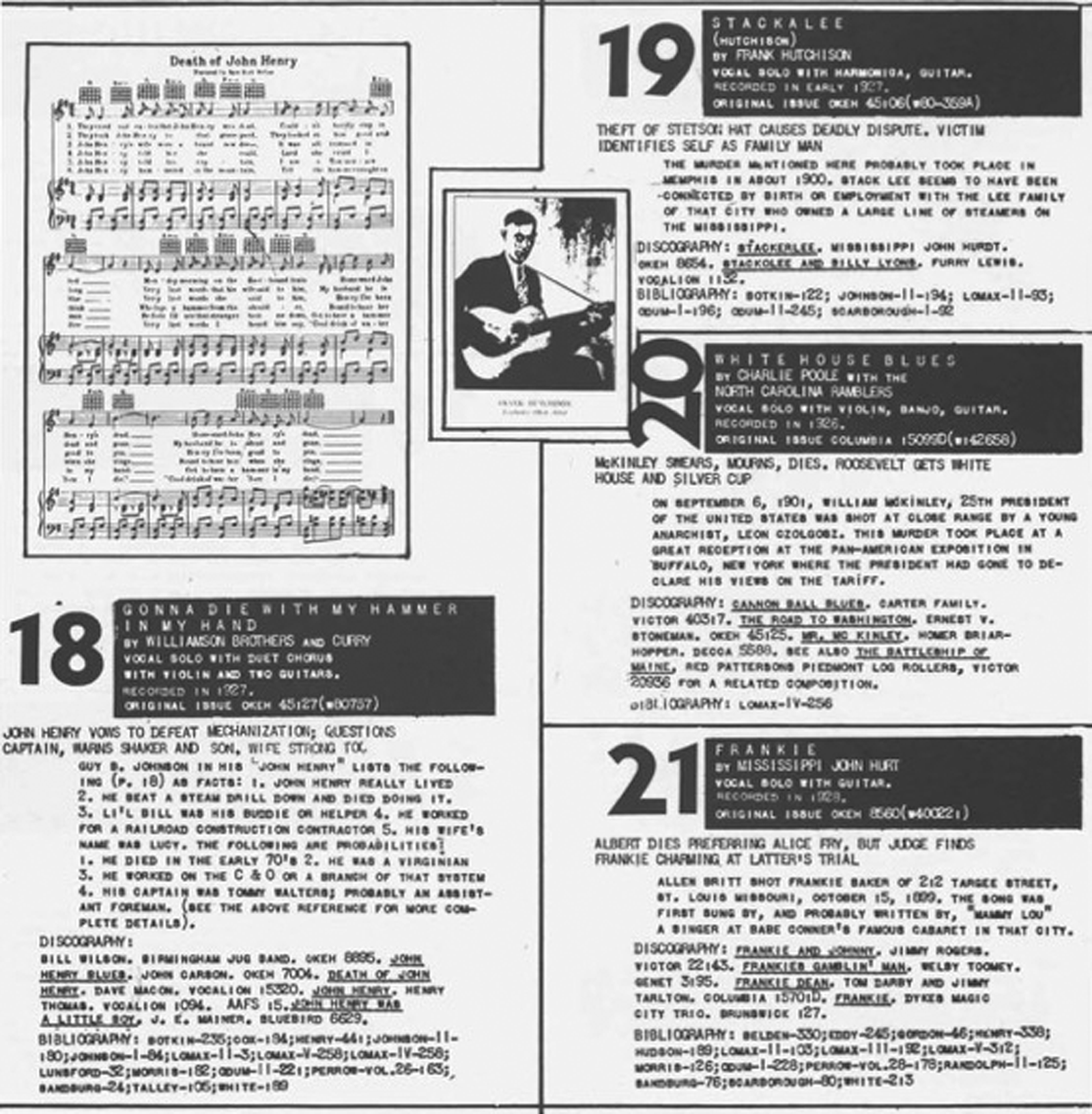

Similarly, Smith embraced the modern and commercial as central to folk music. Although all of the tracks on the album were commercial recordings (rather than ethnographic field recordings), the definition of “folk music” was expansive enough to include, among other things, a novelty jazz band (“Moonshiner's Dance Part One”), a track from a Hollywood Western (“The Lone Star Trail”), and a recent ballad about the Titanic (“When That Great Ship Went Down”). Smith also signals his fascination with the commercial in his liner notes. Some notes are constructed to mimic newspaper headlines and telegraphs, a nod to contemporaneous commercial methods of communication. The notes are also filled with images of catalog advertisements, emphasizing the commercial selling of folk music in the recorded era (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Example of Harry Smith's liner notes for Anthology of American Folk Music. Printed with permission from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

In assembling the Anthology, Smith instead focused on two criteria for inclusion: Unusual and exotic sounds, and historical importance. In one interview, he held that:

The Anthology was not an attempt to get all the best records (there are other collections where everything is supposed to be beautiful), but a lot of these were selected because they were odd—an important version of the song, or one which came from some particular place. For example, there were things from Texas included that weren't very good. There was a Child Ballad, Henry Lee. It's not a good record but it had to go first in the set because it was the lowest numbered Child Ballad. Then there were good performances. The Brilliancy Medley occurs to me. You couldn't get a representative cross-section of music into such a small number of records. Instead, they were selected to be ones that would be popular among musicologists, or possibly with people who would want to sing them and maybe would improve the version. They were basically picked out from an epistemological, musicological selection of reasons.Footnote 25

Unlike collectors of blues and jazz who were concerned with finding the best performances and most authentic renditions, Smith's criteria saw value in a number of tracks that might have otherwise been excluded.

Smith's sequencing and liner notes further elucidate these aims. Volume One, Ballads, is organized chronologically, from the earliest Child Ballads to ballads that dealt with modern disasters: Train accidents, the sinking of the Titanic, and Depression-era farm failures. The liner notes from this volume simultaneously chronicle the histories of the ballads and the U.S. historical events that inspired them. Smith essentially narrates a history of the United States through folk music, positioning folk music as an integral tool for capturing history. In Volume Two, Social Songs, the volume is essentially divided in half, the first dealing with secular music and the second with sacred music. In the sacred half, Smith again uses history as a guiding structure, from the old lined out hymns to the more recent communal singing of sacred harp tunes and hymns with orchestral backing. In the secular half, however, Smith's attention is on geography, noting with care the regional styles heard in each track, giving particular attention to rhythm and instrumentation. The result is a sort of musical travelogue through space rather than time. Finally, Volume Three, Songs, eschews a clear organization, instead intermixing styles and subject matter to suggest a large diversity of American folk music. Blues, jug band tunes, and Louisiana Acadian music all reappear, as do a number of artists from the first two volumes in a collage of different sounds. Likewise, the liner notes sometimes call attention to historical attributes, and sometimes geographic style as on the first two volumes. Rock critic Greil Marcus has read the third volume as highlighting a form of alienation and strangeness, a politically charged opportunity to call attention to the marginalized voices absent from American mythology. He writes, “Part of the charge in the music on the Anthology of American Folk Music…comes from the fact that, for the first time, people from isolated, scorned, forgotten, disdained communities and cultures had the chance to speak to each other and to the nation at large.”Footnote 26

What is perhaps most striking about Smith's work here is the complex, cumulative effect of all three albums. Rather than focus on purity—a common emphasis among Smith's contemporaries—or a single, unbroken narrative, Smith lays out several stories about American folk music, then abandons narrative entirely in the third volume. The essence of American folk music comes across via the diversity of the collection and its purposeful sequencing, or exhibition, in ways that highlight attributes through juxtaposition. In this regard, the collection is not unlike museum exhibits that similarly lay out disparate artifacts, helping the viewer to draw connections. Michael Baxandall praises such exhibitions, noting, “The juxtaposition of objects from different cultures signals to the viewer not only the variety of such systems but the cultural relativity of his own concepts and values.”Footnote 27 For listeners in the 1950s, or now, the music asks us to refigure our ideas of American folk music, confronted by the collection's stylistic diversity, racial mixing, and engagement with commercialism. Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett goes even further, claiming that individual artifacts in museums “were never intended to hold up to scrutiny as singular creations. Moreover, they are at their most documentary when presented in their multiplicity, that is, as a collection.”Footnote 28 Indeed, the original recordings used in the tracks were commercially produced, intended as entertainment, and marketed either to migrant listeners as a means to reconnect with a familiar regional tradition, or to new audiences as novelties; they were never intended as keepsakes or as markers of a national cultural heritage. However in Smith's hands, the acts of collecting and reissuing them indelibly transmuted them into historical documents of American folk music in all its diversity. “In forming collections,” Sharon Macdonald writes, “museums recontextualize objects” and imbue them with distinct cultural value.Footnote 29 The same is true for the Anthology, as tracks are transformed from contemporary music meant for entertainment to historical markers of music history, from regional traditions to a national symbol, disparately gathered and arranged to tell a story, or rather, several stories of American folk music history.

Smithsonian's Decisions: Preserving and Restoring the Anthology

Although Smith was the curator of the Anthology, its function as a public statement on U.S. folk music was no doubt amplified by its reissue by the Smithsonian. Arguably, this process began with the original release on Folkways Records, a label with a national audience (albeit niche) and political attitudes. Folkways founder Moses Asch and Smith shared a philosophical approach to folk music. Both first encountered U.S. folk music through his parents: Asch's father supplied him with books about cowboys and their songs, which he said “guided me through life because [Teddy Roosevelt, in the introduction to John Lomax's collection] said that folklore and songs are the cultural expression of people. So here I had these books and was able to show that we had this kind of uniqueness to our culture which was not just a melting pot, but were part of a whole bunch of other things.”Footnote 30 Asch described his Folkways catalog as a “mosaic” and included music that Smith found appealing, including jazz, avant-garde art music, and anthropologic field records of music from around the world, and of course the reissuing of older records of which the Anthology was a central part.Footnote 31 Asch felt artists should control all aspects of the album design, from theme and selection to cover photos and liner notes. The cover and liner notes Asch felt were particularly important, partly because they distinguished the label at the time, and partly because he was extraordinarily sensitive to the educative possibilities of these albums, adhering to the philosophy “music is music in context” and orienting his releases toward museums, libraries, and schools.Footnote 32 Asch also remained sympathetic to artists with politically sensitive material, envisioning albums as a sort of “living newspaper.”Footnote 33 Thus, just as Smith hoped to see the United States changed by music, so too Asch sought to use his label to further social causes. To support civil rights for African Americans, Asch issued albums with the music and poetry of the movement and coverage of the Nashville sit-in, and to further global and national harmony, he felt that his devotion to U.S. and global folk music were “helping Americans to feel at home with themselves and with their global neighbors.”Footnote 34 To be sure, Asch and Smith did not always get along, in part due to Asch's business-mindedness and Smith's capricious interests, penchant for distractions, and completist approach to documentation. However in Asch, Smith found a producer who shared many of his own aims.

The Smithsonian acquired the Folkways catalog in 1987 and it continues Asch's and Smith's social vision. According to the Smithsonian Folkways website, the label is “dedicated to supporting cultural diversity and increased understanding among people” and seeks “to strengthen people's engagement with their own cultural heritage.”Footnote 35 Prior to the Anthology, the Smithsonian reissued a number of recordings in keeping with this mission of diversity, including African-American music (Sing For Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Its Songs (1990)), Native American music (Creation's Journey: Native American Music (1992)), global musics (Mbuti Pygmies of the Ituri Rainforest (1992)), and American folk music (Smithsonian Folkways American Roots Collection (1996)).

The Smithsonian's decision to reissue the Anthology was buoyed by this mission and shaped by a confidence in its success. Archivist Jeff Place stated in 1997 that the Anthology had been the most requested item from the Smithsonian's catalog since 1988, when he joined the organization.Footnote 36 Confidence was also likely boosted by the success of Columbia Records’ reissue Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings to immense critical and, more surprisingly, commercial success: By 1994, the Robert Johnson reissue had gone platinum.Footnote 37 Envisioning the Anthology reissue, Marketing Director Brenda Dunlap confirms they saw great potential for the reissue: “Given the requests we've received over the Web, and handwritten postcards and that sort of thing, I do see a lot of interest in it. We have kids at radio stations asking about it as well, which is always a good sign, so there is a new generation of interest there, too.”Footnote 38 When asked what sort of audience she would be targeting, Dunlap responded, “We'll be doing mailings to academics at all different levels, American Folk Society members, ethnomusicologists. …In terms of retail, a lot of the folk stores . . . are perfect outlets for it. Places like Best Buy and Borders Books tend to carry a lot of Smithsonian Folkways, and they'll probably have some available. I think collectors will be a large part of this.”Footnote 39 Although hoping to find a new generation of listeners, the Anthology reissue was largely aimed at the extant one, especially those likely to already be aware of it: Academics, collectors, and committed folk enthusiasts.

A fundraising flyer to help with the $146,000 estimated price tag of the reissue further elucidates the principles that guided the reissue.Footnote 40 The flyer again targets the academic aim of the reissue, particularly through the language of canonization and scholarship. It labels the anthology “perhaps the most influential set of records in the history of recorded sound” and describes a “digitally remastered” box set wherein Smith's notes “will be framed by an historical essay, expanded song annotations, testimonials by literary and musical figures, and archival photographs.” The flyer promises it “will be a landmark educational tool for generations.” Likewise, the flyer is designed to appeal to novelty and rarity, including the aforementioned “digitally remastered” tracks and the true if somewhat misleading claim that “This historic collection of sound has not been available commercially for almost half a century.” Furthermore, the flyer adopts an aim of social change by reminding readers of the Smithsonian's mission to provide “models for facilitating public dialogue among diverse ethnic, racial, and regional groups” and contextualizes the original as a fight against consolidation of record companies in the 1950s, which were “producing musical sameness.”Footnote 41 In other words, the flyer—indeed the process of reissuing the Anthology—is best understood as an extension of the Smithsonian's mission of preserving heritage, expanding access, fostering education, and championing diversity.Footnote 42

Perhaps the biggest change from Asch's release was that the tracks had to be licensed under copyright; a long, difficult process of retracing the conglomeration of numerous now-defunct recording companies and seeking copyright permissions that represented over 40 percent of the total cost, and which largely benefitted Sony.Footnote 43 When these records were made, record companies sought out ballads and other folk material that was not subject to copyright; performers were usually given a lump sum, that is if they were paid at all, and the recording company held the rights to the recording. The Depression left companies with large stockpiles of unsold records, which became the cheap source for Smith's collecting habit as stores tried to clear out space, and during World War II, the records we melted down for shellac, rendering what was on the record economically inert. Once the recordings found new listeners, Asch skirted musicians’ unions to record during the strike in 1942, and later used Folkways to return ownership of the nation's folk music to the nation, using subsidiary labels to help protect him from charges of piracy. Asch went through several legal battles following his reissues, but successfully argued that the public had a right to hear this music and that if record companies were no longer willing to make these recordings available, they could not block his efforts to make the music available to the public.Footnote 44 Victor records disputed his reissue of Woody Guthrie's Dust Bowl Ballads after it became profitable, but Asch insisted, “cultural property belongs to all and is limited to individual ownership only in so far as the copyright of the material is subjected to and limited to. …[R]ecords do not carry this copyright.”Footnote 45

For the reissue, the necessity for copyright was simply a matter of fact. A memo from March 7, 1996 elucidates the confusing path to obtaining it:

MCA's inability to clear tracks has to do with the ambiguity of their ownership of the Paramount catalog, and we are looking into potential alternative repertoire owners. BMG's delay seems to come from the amount of research involved in clearing this quantity of tracks. Many of these tracks are obscure and may not have been used since they were licensed for the original release of this album in 1952. Although these tracks were legally licensed for the original issue of this package, today's licensing administrators may not feel confident licensing material without the proper contractual proof. Also, catalogs constantly change hands.Footnote 46

The modern necessities behind the licensing of the reissue make the commentary in the aforementioned fundraising flyer about musical conglomerations even more pointed, although once in production the Smithsonian rarely made any similar references, perhaps not wishing to jeopardize Sony's cooperation with the project.

Once licensed, the tracks had to be located and in many cases cleaned up. Peter Reiniger, the sound engineer, began by examining the master tapes held by the Smithsonian and documenting for each the crackles, clicks, splices, dropouts, skips, distortions, and noises from the wind or passing vehicles, or inabilities to discern instruments. Two tracks by Dave Lunsford, numbers 51 and 63, were simply directed to an extant reissue on CD. Only three tracks, numbers 7, 8, and 27, merited a simple “pretty good,” whereas for twenty-one tracks Reiniger suggested an alternate source be sought. A second, unsigned list directing the reader to locate sources almost exactly replicates Reiniger's original list. A third list, also unsigned, notes that alternate sources should be found for nine tracks and should be considered for eleven tracks, only partially overlapping with Reiniger's recommendations (Table 1). In other words, what merited an alternate source was somewhat subjective. Using Reiniger's notes, I can find no clear pattern to gauge what sonic defects prompted a track's rejection in favor of an alternate source. The reissue ultimately used alternate sources for twenty-seven tracks, only partially overlapping with these lists, suggesting some desired alternate sources may have proven impossible to find, while others may have fortuitously presented themselves.

Table 1. Tracks selected for replacement with alternate sources on the reissue of Anthology of American Folk Music

A, notes from sound engineer Peter Reiniger; B, first unsigned list; C, second unsigned list (“(X)” for “also considering”); D, CD reissue.

It was fitting that the reissue relied on the availability of clean copies among collectors, the same strategies Smith employed in building his own collection. Striving for the cleanest sound possible aligns with what Asch's believed: “With my records, I think if I am documenting a thing, then I want as good quality as possible, because the person 20 years from that time should be able to reconstruct what I recorded.”Footnote 47 Nevertheless Asch opposed any electronic manipulation, resisting the move to stereo as much as possible. So, although the fundraising flyer and reviews continually touted the digital remastering of the Anthology, the Smithsonian appears to have ultimately hewed somewhat closely to Asch's philosophy. Reiniger comments in the reissue, “We have consistently adhered to the idea that it is far better to listen to some noise with the music than to eliminate all the noise and a good part of the audio spectrum with it,” though he also admits that pitch justification was used to account for the variance of turntable speeds, and that other technical enhancements may have been employed.

The decision to leave in the noise no doubt appealed to vinyl enthusiasts, collectors and traditionalists among them, who regularly criticized digitization for its compression and diminishment of the richness of the sound. However sound quality would not be the only thing lost. The presence of that noise confirms the historicity of these recordings—that what you are hearing is not a new CD box set at all, but an old recording, a vinyl LP or even the noisier shellac of the original 78s. Scholars have noted the continued championing of vinyl over digital as an exercise in nostalgia and authenticity, perceived as communing with or listening to the dead, physically preserving a historical item.Footnote 48 In their study of reissues of Glenn Miller's “In the Mood,” Christina Baade and Paul Aitkin found that many listeners found the presence of “‘flaws’ of ‘pop and crackle’ enhanced their connection with the past” on those recordings.Footnote 49 This effect is akin to what museologist Peter van Mesnch calls “patina”; the “historical process of interaction between the object and its environment” that “creates an atmosphere of authenticity and historicity.”Footnote 50 Reiniger's work directly parallels that of a museum restorationist. As Johnathan Djabarouti observes, “the relationship between restoration and authenticity in conservation is traditionally related back to the notion of patina,” where “old things are perceived as having more inherent value.”Footnote 51 Of course, recordings are distinct from many traditional artistic works in that recordings lack a distinct and unique original, which is especially true in the act of reissuing. By retaining the patina of auditory imperfections, much like the decay of an old building, the reissue grants an aura of authenticity often lacking in reproductions, as Walter Benjamin famously theorized in his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.

The effect for the listener effectively mirrors the palimpsest effect listeners of the original had: The feeling that what you are hearing is from a distant and strange past whose traces remain buried under the present, the performers long dead. Recall again author William Gay remarked that the voice of Dock Boggs on the Anthology was “so dissociated it seems to be coming not just from some other time but from outside time itself, from beyond the pale, a voice half-filtered through a mouthful of graveyard dirt,” thus tying the act of listening to disembodiment, death, and decay.Footnote 52

The reissue, released during the vinyl revival of the 1990s, retained the distinct sound of the record, as potent a symbol as the sepia tone of old photographs, preserving this paradoxical aesthetic immediacy of temporal and corporeal distance. The interest in vinyl has also been understood as a subcultural move in opposition to the recording industry.Footnote 53 This attitude echoes the Smithsonian's characterization of the original album as doing the same, defiantly refusing to play by the industry's rules. However the reissue itself sought a more commercially viable approach, released not on vinyl but also on CDs, which only carried the sound of the vinyl LPs and shellac records.

If the sound was designed to mimic the effect of the original, the look of the reissue was practically indistinguishable. This aesthetic was not, however, the goal from the start. An email describes the initial plan as an inexpensive reissue: A set of three simple, $6, 2-CD reissues, very much in line with Asch's mission to ensure public access to folk material.Footnote 54 The production team, however, felt the Anthology demanded a box set treatment. To be sure, the high retail price of the resulting box set, $79, helped to offset the extraordinary cost of licensing all the tracks, something a non-profit public organization would have trouble shouldering. However, the price tag also reflects the shift of their target demographic from new audiences to audiophiles, collectors, and educational institutions. Minutes from a production meeting confirm that the decision was guided not just by economics, but also by a more emotional attachment to the Anthology as a collector's item, as production team members wondered, “How will we maintain the integrity of the original work if we don't do it all at once in a 12 × 12 box set?”Footnote 55 I draw particular attention to the characterization of the Anthology as a “work,” implying it was not simply a collection of tracks but a fully realized whole, placing the emphasis on Harry Smith as the visionary artist.

Maintaining integrity, as it would turn out, meant replicating the look of the original boxes of LPs, material, size, and all. The outside label replicates Smith's original cover: A copy of a celestial monochord engraved by Johann Theodor de Bry taken from a publication by Robert Fludd. The simple addition of a frame around it is suggestive, elevating the cover image, and by extension the whole Anthology, to the realm of a museum piece to be preserved. Like any museum piece, Smith's cover was effectively restored, having been replaced in the 1960s by Irwin Silber, who selected a 1935 photograph by Ben Shahn of a rehabilitation client in Boone County, Arkansas. It was Shahn's image that was used in the fundraising flyer, perhaps to resonate with the flyer's more political claims, or perhaps simply to cater to a familiarity with the more commonplace image that had fronted the album for three decades.

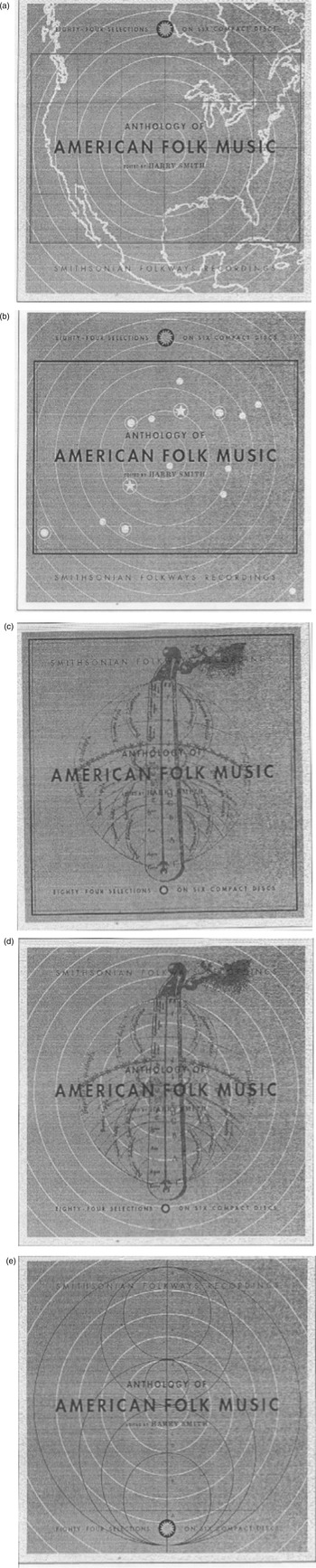

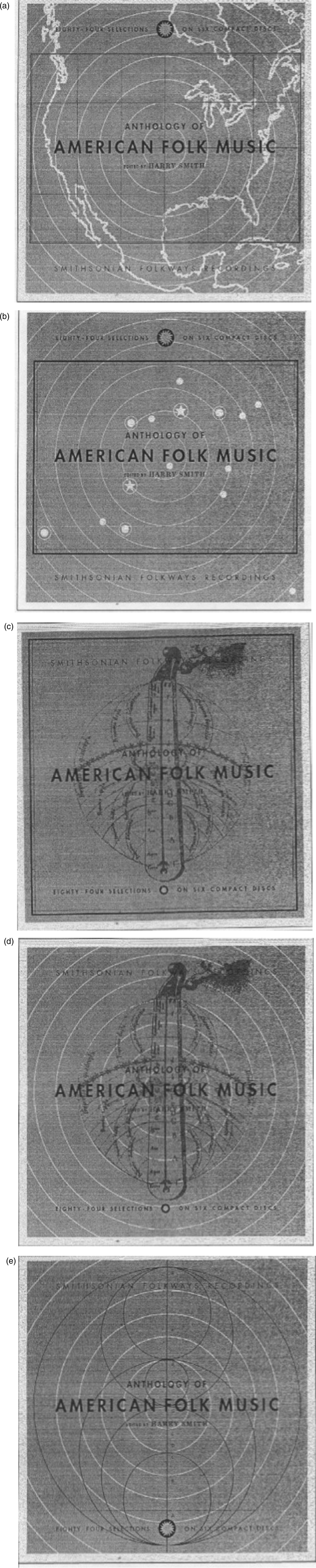

Returning to the original was not the obvious choice, however. Five covers, including the selected original, were proposed by designer Scott Stowell (Figure 3). The first depicts an outline of North America, with radio waves emanating from the center of the image, from the iconic heartland (rather than the South). Stowell writes, “This solution keeps the things that we liked about the original version (including the general concept) while making the map a much more non-political image. Instead of talking about the U.S.A., this becomes a window onto this part of the world, without political boundaries of any kind, and thus could be from any time period, 1952…1927–32…or even centuries before.”Footnote 56 From this, we can glean that the original image was neither the Depression-era photo, nor the monochord, but at heart a map of the United States, playing up the nationalist aspect of the Anthology reissue. Nevertheless there must have been concerns, and the solution was to create a United States without borders, something I have argued was very much at the heart of Smith's vision, as well as a sense of timelessness coupled with the modern technology of radio, a central tension in the Anthology. A second image retains the radio waves, and scatters around them stars and circles. Stowell notes it “has one foot in Harry Smith's mystical world of the Celestial Monochord, and the other in Smithville…. What look like stars in some sort of celestial diagram are actually towns and cities from a map of the Southeast (or in this case, from a Crossroads CD label). The radio waves here are emanating from people in the villages, towns, and cities that could be anywhere, at any time.” Here, the mythology of the South, central to Smith's vision of the folk, is present, if abstractly, while the concept of timelessness is again emphasized. Versions three and four feature the monochord image, one without and one with radio waves. Stowell preferred the one with the radio waves because it made “a direct connection between the ancient and the modern, and by extension between the myths and traditions on the Anthology and modern listeners.” The fifth design abstracted from the fourth the circles of radio waves and the circles emanating from the monochord—precisely what he liked about the relationship in the fourth design. Nevertheless he also felt he should add text “much like the type used in the booklet,” presumably because he feared the design was too abstract.Footnote 57

Figure 3. Five suggested cover designs for the reissue of Anthology of American Music. Printed with permission from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

The selection of the original does not appear to have been made by Stowell, whose enthusiasm for that design was muted—possibly because he, as a graphic designer, had very little to do with it. As such, I would venture the image was included on request from someone at the Smithsonian, a strong enough recommendation that Stowell visually or textually referenced the monochord in four of the five designs. Indeed, Stowell's designs effectively bring together the past—Harry Smith's original celestial monochord—and the present day, characterized by the technological radio waves and geographic allusions to the United States, mirroring the intermingling of past and present, regional and national/international that Smith's Anthology undertook. Only the first, which was a continuation of some unretained earlier design plan, made no reference to the monochord. Nevertheless it was the third, which made no reference to the modern American present, that succeeded through its historical accuracy and continuity, and the perceived purity of Smith's vision.

This preference for Smith's original vision, elevated to a museum piece, was evident nowhere more clearly than the booklet. The original booklet was perhaps the hallmark of the Anthology, totally unlike anything else. As the producers take pains to note, its inclusion in the reissue was a precise facsimile:

Enclosed is a facsimile of Harry Smith's original handbook, which he composed, designed and laid out himself. There have been several reprintings since the original edition, each with changes in art, copy, and design. This reproduction is faithful to Harry's creation. It has been produced with the same reprographic methods in use at the time of the original edition: film negatives were shot with a photostat camera from a printed copy of the 1952 handbook because the original mechanical boards had been lost. We did no retouching or cleaning up and made no changes to the original art or copy. Offset plates were then made from these negatives, and paper was selected to match the original. The result is a reproduction which is as close as possible to the original artifact.Footnote 58

The language here exceeds the language regarding the audio transfer, proudly touting the absence of any retouching or alterations, the careful selection of the smallest details, and seems to comply with the goal of maintaining “the integrity of the original.”

The language here treats the reissue itself as a work of art. It makes explicit the level of craft in its construction, validating Smith's artistic vision and the careful work of the Smithsonian simultaneously. Although the Smithsonian's reissue was not a single artwork, as it was a mass-produced recording, their marketing of it as a high-priced, elaborate collectible for connoisseurs rather than a cheaper, simpler (and more accessible) version, the reissue is positioned closer to an original work of art than, say, the mass-marketed posters one might buy in a museum gift shop. In other words, reissuing is rendered as a culturally distinct process from mere reproduction.

Accompanying the original booklet in the box set are “supplemental notes” crafted by Jeff Place in a strikingly similar aesthetic: Tracks are arranged in vertical columns left to right, each introduced with a large number on the left, with label information next to it. Both Smith and Place create similar keys to the annotations in their introductions. Place even scatters a few images throughout the notes—certainly not to the extent of Smith's original notes, but enough to recall it. Place's notes, all meticulously researched, largely focus on performers that Smith wrote little or nothing about, or corrects Smith's various erroneous dates and instrumentation. In this regard, Place most directly takes on the role of curator, labeling the artifacts and providing critical historical information, even when doing so undercuts the authority of Smith's original. Producing side-by-side notes creates a dual narrative that preserves Smith's narrative while deepening the listener's understanding of the tracks’ history prior to Smith. Moreover, Place recognizes a crucial dilemma for the curator: A mission to educate and a desire to let Smith's work speak for itself. Susan M. Pearce reminds us that “the relationship of the professional curator to the public, and the balance of power within such a relationship raises questions about ‘whose history?’ and ‘produced for whom?’”Footnote 59 In many ways Place cedes his own authority to Smith, downplaying his role as merely “updat[ing] Smith's notes as necessary.” In this regard, his relationship to the public is somewhere between historian and preservationist, in many ways unwilling to dramatically recontextualize Smith's history, despite its limitations. The result is something of a paean to Smith, even as Place describes these notes as a way to move not back but forward: “Personal portraits, social landscapes and historical perspectives intended to lead you on your own to find out more. …Hopefully, the new Anthology will evolve with new channels for exchanging information and will serve as a model for presenting important audio recordings to an interested public.”Footnote 60

Although Place's comment invokes the individual tracks as “important audio recordings,” the performances seem secondary to the elevation of Smith as the true author here. Reverting to the original cover design, carefully reprinting Smith's liner notes, and even minimizing the corrections to Smith's errors in those notes—all of this suggests Smith's Anthology is a sort of Urtext, especially considering the production team's commitment to “the integrity of the original.” This approach to reissuing is quite different from Smith's, and different from the original recording process as well. The original recordings were hardly definitive recordings, edited by producers and but one of many versions of each song. Smith's approach to reissuing took a heavy and overt editorial hand; the Smithsonian, by contrast, sought to minimize their imprint. Moreover, although Smith used the Anthology to illuminate folk practices of the early twentieth century, using juxtaposition and fragments to defy narratives, the Anthology as reissued by the Smithsonian emerges primarily as a document of the 1950s folk revival, seen in the language of their flyer and in their discussions. It fits into existing narratives about that time—a snapshot of a moment of social upheaval, and a singular creative work by a single figure. That approach guided the process of collecting additional notes about the Anthology's cultural impact as an object.

Smithsonian's Decisions: Narrating History

Perhaps the most active role the producers of the Anthology reissue played was in the additional notes that accompanied the box set. In a memo from editor Peter Seitel from October 17, 1996, he urges that the notes should cover four principal areas:

(1) What does this musical snapshot taken in 1928–32, the Harry Smith Collection, represent? How is our picture affected by the means of recording at the time—the technical equipment and the social organization/economic practices of the music industry at the time? Who are these people and what is their relationship to the music that they sing?

(2) What was the impact of this collection on American music?—told both anecdotally…and based on the evidence of styles and repertoires of subsequent musicians. …

(3) What does this collection represent in the context of Harry Smith's work? …

(4) What can be added to the annotations of individual songs in terms of their significance or their history from 1952 to the present?Footnote 61

Seitel maps out an ambitiously thorough and scholarly assessment of the Anthology and its historical contexts. This appears to have held some sway early on. An undated memo remarks that:

We have notes from Jon Pankake (which appear to be for volume 4). Note in the file from Kate Rinzler saying that they are too personal and need to be focused to include comments on the early recording industry and the anthology's impact on it in the early 50s. She says Mike Seeger will talk with Pankake and ask him to revise the notes. The first question is which volume do these notes go with?Footnote 62

Here, the desired tone for the notes is similarly scholarly and contextual, with even less room for personal reflection than Seitel's, which allowed for anecdotal tales. An early list of names of potential contributors demonstrates producers cast a wide net, endeavoring to cover the anthology from multiple angles (Appendix 3B). Musicians made up the largest share, covering a wide range of styles and generations: Bono, Laurie Anderson, Michael Stipe, Loretta Lynn, Ornette Coleman, Patti Smith, Johnny Cash, Pete Seeger, Oscar Brand, Phil Spector, Beck, Doc Watson, Yoko Ono, and Bob Dylan. Colleagues and collaborators with Smith like Moses Asch, Peter Bartok, Jon Pankake, Allen Ginsberg, Sam Charters, and Ralph Rinzler were naturally included, as were a variety of prominent artists and intellectuals: Thomas Pynchon, Robert Frank, Sam Shepard, LaMonte Young, Dennis Hopper, and Amiri Baraka.Footnote 63

Rani Singh, the director of the Harry Smith Archives, sent an update on the status of notes. Notes had been received from several artists: Eleven of them constituted long, multiple page remembrances, whereas others offered short anecdotes or pithy, heartfelt comments. Singh indicated that she needed to edit Taylor's and lightly edit Rinzler's note, and that Pankake's eight-page contribution, by far the longest, could be edited though she didn't want to do so. A host of other contributors had also committed to the project, though they had not sent anything in, and still several others Singh remained hopeful about getting involved. Singh's approach retained the wide variety of viewpoints that could touch upon all four of the areas recommended by Seitel: Big name performers to draw attention to the Anthology's impact; others who assisted the folk movement behind the scenes through production and management like Young, Rooney, and Pearl; colleagues to offer a deeper account into Smith like Asch, Rinzler, Saunders, and Ginsberg; and a number of scholars and writers who could provide the appropriate historical and cultural context—Kahn, Cantwell, Sante, Heylin, and Ivey, who would soon chair the National Endowment for the Arts.

Singh was also particular about the ordering of the notes. In her plan, the set opened with her own contribution as director of the archives, followed by critic Pankake, fellow record collector Kemnitzer, musicians Stampfel and Von Schmidt, musician-scholar Cohen, scholar Cantwell, musician Fahey, friend and collaborator Ginsberg, and ending with Pirtle. The placement of the contribution by Moses Asch, she said, still needed to be decided, if it was to be included at all. There's a Smith-like flow to the arrangements: The two scholars together in the middle, musicians on either side, and the two poets at the end. Furthermore, her insistence upon Pirtle to close was meaningful, for Pirtle's rather touching note tells of how he reintroduced Smith to the album in his later years and how Smith had been moved to tears by the experience, providing a logical conclusion to the narrative shaped here. Smaller pieces were to be scattered throughout the document—as many as could fit.Footnote 64

The final result was much smaller in scope than either Seitel or Singh had hoped. No doubt this was a practical move to keep costs down and maintain a manageable size. Nevertheless it also bears the distinct imprint of a careful editorial hand. Although some recollections were scattered throughout, as Singh had envisioned, only four were “short”; indeed, six authors who had contributed longer works were excerpted and placed in the margins of multiple consecutive pages, much like magazine articles that are continued on later pages in thin columns. The prioritizing of longer works may have stemmed from wanting to recognize the effort that went into crafting them, or possibly from agreements made with the authors, but it also speaks to the scholarly and documentary aims the collection had, giving the volume some heft.

The essays given pride of placement in the anthology are particularly scholarly or historically minded: Neil Rosenberg's essay on recording practices of the 1920s and 1930s, Luis Kemnitzer's in-depth look into the practice of record collecting, Jon Pankake's personal yet detailed remembrance of the Anthology and the folk revival, and Moses Asch's recollection of the album's conception and production.Footnote 65 Biggest of all was a full twenty-one pages devoted to an adapted excerpt from Greil Marcus's chapter on the Anthology from his just-published book on Bob Dylan, Invisible Republic.Footnote 66 Marcus's name did not appear at all in earlier documented plans for the notes, but the decision to excerpt part of a book, rather than to devote the space to other notes, speaks again to the scholarly ambitions of the reissue. However given that other scholars like Robert Cantwell had submitted contributions, the selection of Marcus, a more public and famous figure, suggests that commercial appeal was also strong; Marcus offered the right combination of scholarship and fame to match the competing goals of the organizers. Other contributions scattered throughout the margins largely gave anecdotal color: Personal testimonials about the Anthology's impact on their work and reminiscences about Smith's eccentric behavior. It was to these margins that Pirtle's essay, with which Singh wanted to close the notes, was inconspicuously consigned.Footnote 67

More telling is what was collected but not included. The producers steered clear of anything too critical or controversial. Sam Charter pointedly asked in his note, “Why do you want to propagate the myth of Harry Smith? He wasn't doing anything that anyone else wasn't doing at the time.”Footnote 68 Pat Conte used Smith's Anthology to critique other anthologies, such as Henry Cowell's 1951 Music of the World's Peoples, which he deemed “seemingly arbitrary in selection, and lackluster in production, critiqued with vague musicology,” and thus sought to bring Smith's revitalizing energy to future global music projects.Footnote 69 Neither note was included in the final product. Although it's unclear who edited Marcus's text for his extended note, a few details from the full chapter were excised. In one, Marcus notes that Smith “liked to brag about killing,” which certainly might prove controversial and cast Smith in a negative light.Footnote 70 In another, Marcus describes how “devotees surrounded him” when he died.Footnote 71 Because this detail was omitted, Smith is more easily interpreted as a forgotten or misunderstood genius, not unlike the prevailing view of the artists his album featured. These decisions serve to enhance the mythology surrounding Smith.

The Smithsonian also excluded some more pointed critiques. Steven Taylor's contribution, which was not printed, extensively discussed the racial and commercial exploitation inherent in these older recordings. Indeed, one of his critiques echoes the Smithsonian's criticism of media conglomeration, albeit more strongly worded:

A number of factors contributed to the virtual disappearance of the music represented on the Anthology. One major factor was the Great Depression, another was radio, and a third was the increasing consolidation and monopolization of the musical mass media by Tin Pan Alley—a group of mostly white men, most of whom had no direct experience of African and European American folk musics, and many of whom had never ventured outside of New York City, but who had the business acumen to monopolize the national publishing, performance, and broadcast media with their catalogs of “hit” songs periodically refreshed by the selective appropriation of “Negro” or “Hillbilly” affects.Footnote 72

Including this charge of white men might have been incongruous with the reissue, all of whose contributors were, in fact, white men.

This evasion of racial issues underscores a central paradox of the Anthology and its influence on the folk movement. The Anthology had been leveled at a segregated society, and yet the folk and avant-garde movements it fed were dominated by white men. The reissue of Anthology was never able to come to terms with its racialized history. More troubling still, it seems to deliberately skirt the issue, for one of the very few instances I could find where a contributed note was edited for inclusion—indeed, the only substantive edit—was Eric Von Schmidt's account of his introduction to folk music. Schmidt's note in the anthology ends with his description of his group of folkies as romantics, and details how he named a boat after John Hurt, how another friend hoped to find Blind Lemon Jefferson's grave and sweep it (a reference to his song on the Anthology “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean”), and how he mourned the fact that Leadbelly had died before he met him. This is where the reissue note ends, on a moment of pathos and indebtedness. Von Schmidt's paragraph continues, however, in the original draft: “It was a mostly white, middle-class bunch of college kids calking up little discoveries on the slates of their young lives.”Footnote 73 The omission of this line speaks volumes about all that the reissue does not say about race, class, and status.

The editorial excisions here seem designed particularly to avoid deeper conflicts about the legacy of Smith and the folk revival in general. Although no documents I examined discussed the editorial process, such decisions are perhaps best understood in the context of another Smithsonian event: The cancellation of the Enola Gay exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum in 1994. The exhibit came under intense protest from politicians and veterans groups, who claimed the exhibit's negative tone and its ambivalence toward the action of dropping two atomic bombs on Japan was disrespectful of veterans. As Richard H. Kohn details, the Smithsonian repeatedly edited the exhibit, which only succeeded at alienating historians without allaying the concerns of the veterans and politicians.Footnote 74 Ultimately, the exhibition was canceled to avoid further controversy. Although the Enola Gay exhibit was perhaps foremost in the Smithsonian's memory, it was not the only politically charged exhibition. The 1980s and 1990s saw a growing contention between political arts and the government—broadly described as “the culture wars”—including an infamous Whitney Biennial in 1993, which featured politically engaged and confrontational works by women, queer artists, and people of color, that was largely reviled by (white, male) reviewers.Footnote 75 In this light, the notes for the reissue perhaps seek a balance—between the scholarly and the commercial, the historical and the personal, the insightful and the uncontroversial. Given the success which greeted it, that balance was likely found.

Reviews of the reissue were positive, and unsurprisingly, much of the praise echoed how Marcus and the Smithsonian framed the Anthology. Although the artists heard on the discs received some attention, Smith received the lion's share of credit for the work: David Fricke's review for Rolling Stone even goes so far as to describe Smith as “an alchemist turning familiar, base materials into something precious and enduring.”Footnote 76 By suggesting that the tracks themselves were merely “materials,” rather than worthy in their own right, Fricke positions Smith as the true artist whose Anthology shaped them into a timeless work of art. Geoffrey O'Brien in the New York Times similarly calls the work a “one-man cultural revolution,” a statement that again promotes Smith over the artists.Footnote 77 This attitude may be partly due to the popularity and familiarity of several artists on the Anthology, some of whom had received other reissues. Nevertheless this familiarity, it must be acknowledged, is due to Smith's reissuing work, and this framing is a shift away from how Smith's original reissue was understood, as listeners and especially musicians were drawn more to the performances, leading to performers reviving repertoire, folkies conducting oral histories with performers, and even a few performers having second careers revived thanks to the Anthology.

Reviewers also repeatedly seized upon Smith's racial mixing of artists and repertoire as bold, iconic, and political. O'Brien calls the mixing “Smith's most utopian gesture” and Robert Cristgau in Spin contextualizes it as preceding many of the milestones of the Civil Rights movement, even as he betrays his own racialized essentialism by admitting that he prefers the Black artists because they are “less repressed, musically and sexually.”Footnote 78 Scholars have gone even further in touting the revolutionary equality of the album. In his note, Marcus reads the songs as giving voice to racially and economically marginalized figures, summing up the album's effect as “a great victory—a victory over decades of losing those who did have the courage to speak out in the sociologies of their poverty—that anyone can now hear these men and women, and those they sing about, as singular, as people whose voices no particular set of circumstances could even ensure would be heard.”Footnote 79 Others have followed suit; John Street reads the entire album as a journey from enslavement to freedom.Footnote 80 Such readings not only echo Smith's own racially progressive views, they also evince the “culture war” climate, heralding the anthology as a diverse vision of the United States as a utopia, albeit one whose program of “color-blindness” was broadly acceptable, unlike the racially confrontational exhibit at the 1993 Whitney Biennial or the racial critiques edited out from the notes.

At the same time, certain critiques display a misreading of Smith's vision that served the contemporary political climate. Many read the Anthology as a McCarthy-era critique against consumerism and conformity, a position acknowledged early on in the Smithsonian's fundraising flyer, and echoed in Marcus's note: “The Anthology of American Folk Music was a seductive detour away from what, in the 1950s, was known not as America but as Americanism. That meant the consumer society, as advertised on TV.”Footnote 81 Robert Cantwell fixed his critical ear on the penultimate track, “The Lone Star Trail,” taken from a Hollywood film, suggesting the song was nothing more than an absurd, if ingenious, intrusion “utterly out of place.”Footnote 82 William Gay and John Street make Cantwell's critique even more explicit. Gay hears it as urging the listener to reconsider “the tale you have been told about a lost America,”Footnote 83 and Street calls it “a deliberate impertinence that reminds us of white America's willingness to airbrush out exactly the kind of pain and unabridged oppression that the preceding songs document.”Footnote 84 These critiques highlight more confrontationally both the whiteness of the cowboy figure and, to a lesser degree, its blatantly commercial status, and perhaps assumedly fictionalized roots in Hollywood. Due to the rise of Marxist and cultural criticism among scholars, such claims are unsurprising; they find confirmation in Smith's role as a progressive figure. Nevertheless, Smith's own commentary contradicts these claims. He praised the track as “authentic ‘cowboy’ singing,” and continually embraced the commercial aspects of the music he selected.

Conclusion

In his review of the Smithsonian's reissue of the Anthology, Geoffrey O'Brien reflects on the age of box-set reissues:

It provides further confirmation that the CD box set is, in its reverent attention to detail, our moment's equivalent of the medieval illuminated manuscript. It is not enough to have learned how to capture sound; there must be an appropriate monument to enclose it and keep it from escaping.Footnote 85

Comparing the reissue to an illuminated manuscript suggests that the reissue is more than a simple reproduction of a recording: Rather, it is an object of lasting value. For fans, the reissue is just that: A cherished collectible. Historical and retrospective reissues often tout their rare and unreleased tracks and photographs, suggesting their collectability as unique historical items despite their broad commercial availability.

Reissues traffic in “authenticity” in a way that complicates Walter Benjamin's critique of reproductions of artworks. Not incidentally, Benjamin also invokes the medieval manuscript in his definition of authenticity, observing that:

The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity. Chemical analyses of the patina of a bronze can help to establish this, as does the proof that a given manuscript of the Middle Ages stems from an archive of the fifteenth century. The whole sphere of authenticity is outside technical—and, of course, not only technical—reproducibility.Footnote 86

In O'Brien's metaphor, however, the reissue is the medieval manuscript, not the reproduction of it. How, then, do reissues promise authenticity, or “aura,” to use Benjamin's term? To be sure, not all reissues and compilations do. Nevertheless more elaborate reissues, which gain critical praise and are usually sold at a higher price, frequently invoke this idea in fans and critics. Benjamin roots authenticity in the original's “presence in time and place, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.”Footnote 87 For audio recordings, authenticity would seem to be an impossibility; indeed, Benjamin positions recordings as reproductions.Footnote 88 However even if Benjamin might not grant reissues authenticity, fans do in ways that suggest they display original artifacts of sound just as museums exhibit original artifacts. Recording is not the object but rather the medium to display performance—a fleeting occurrence that otherwise leaves no physical object (as opposed to a classical composition, where the score is the primary object). Reissues invoke their rootedness in a historical time (if not place) and cast their product as rare and collectible, offering unfamiliar or previously unreleased material. Smith did this in the Anthology, introducing records that had fallen out of the public ear—forgotten recordings by obscure artists that cast new light on U.S. folk music traditions. Reissues also employ the scholarly language of historians and preservationists through their liner notes and attention to detail. When the Smithsonian emphasized replicating Smith's own reproduction methods, paper, and not cleaning up the images or tracks, they worked to reassure buyers that the reissue was “the real thing” by collapsing the original and the reissue.

O'Brien's review also describes the reissue as a monument, “enclosing” the music, fixing it fast and locking it away. I find this description telling, yet I would argue that the process of reissuing is paradoxical in this regard. Reissues do have the power to fix musical history. They speak with authority in their scholarly and completist approach. In doing so, reissues have the power to canonize artists and songs, and to shape historical narratives of music. Nevertheless as I have argued, the act of reissuing also has the potential to unfix musical history, as reissuers highlight hidden histories and marginalized voices, and juxtapose tracks in provocative ways. The very power of Smith's anthology came in the ways it unsettled essentialized myths about folk music's relationships with commercialism and race. However, listeners must be wary of accepting any reissue's suggestion of a “complete” or “definitive” account of history, often part-and-parcel with claims of authenticity; as the Anthology reissuing process demonstrates, reissues are the product of interpretation and negotiation, and thus limited by the reissuer's perspectives, values, and biases, as well as their own commercial needs. Gyan Prakash offers a similar warning against the museum's display of artifacts as objective:

Exotic artifacts are positioned as authentic residues of myths, practices, values, and forms of organization that are thought to underlie the wholeness and integrity of other cultures. Such projections of authenticity and wholeness project the exhibition of exotic cultures as entirely separate from and unaffected by the structure that gathers and stages them.Footnote 89

In other words, reissues have just as much to say about the values of the present moment as they do about the past.

The Anthology of American Folk Music highlights the act of reissuing as provocative and meaningful. The very fact that Smith emerged as a canonic figure of U.S. folk music because of his reissue attests to this power. Reissues, including the Anthology, become a means of narrating U.S. history. With each step, the narrative changes. The original folk songs and ballads on the Anthology recounted historical events as part of a flexible oral folk tradition. The original Anthology unveiled a complex narrative of musical evolution and diversity in the United States. Moreover, the CD reissue narrated its own history of the folk revival of the 1950s. Reissues remain potent sources for music historians because of their interpretive work and their potential to tell multiple histories. As a rare example of a reissue whose process has been documented, the Anthology offers a blueprint for further work to interrogate the histories reissues curate and construct through sound.

Dan Blim is an associate professor of music at Denison University. He has published on U.S. music topics, including the political reception of the score for Robert Altman's Nashville, commemoration in John Adams's On the Transmigration of Souls, political ideology in the music at the 2016 U.S. Presidential Inauguration, and narrative realism in filmic adaptations of Broadway musicals.