The essentials, behind the elbows, for emergencies, gold, hand-held and heart–mind mirrors, pointing south and pointing to one's palm, within or hung from the sleeves – these are just some of the metaphors found in Chinese medical titles from late antiquity through the late medieval period. In order to establish a shared foundation for comparing metaphors in European and Chinese book history, this article first presents an overview of how the hand metaphor was used to distinguish certain types of genre for ‘learning by the book’ in European history.Footnote 1 Then turning to Chinese medical history, it begins with the earliest terms designating genres among the known medical titles in Chinese antiquity. Authors used a variety of new metaphors, including those related to hands, to signal new textual forms in early medieval Chinese medicine. But by the late medieval period they preferred the finger-based metaphors of ‘pointing south’ and ‘pointing to the palm’ to hand-based ones for most medical genres intended for ‘learning medicine by the book’.

Hand metaphors in European genres

Using the metaphor of hands to convey genres of books that are handy, at hand and how-to-oriented appears obvious in English. In fact, ‘handbook’ and ‘manual’ now refer so commonly to do-it-yourself (DIY) genres, at-hand references and handy guidebooks that one rarely stops to consider the semantic significance of the hand as metaphor, or, for that matter, how the genres of the manual and handbook emerged. The etymological background of these terms for texts conveying technical knowledge is complex yet appears remarkably coherent.

In European languages, the Latin manuale (Latin manus, ‘hand’), became manuel in French, Manual in German, and manual in English. The history of le manual scolaire (i.e. textbook) in Europe, for example, has been well analysed as integral to the history of education as well as epistemology from several angles – lexically, semantically, materially, categorically and typologically.Footnote 2 In Greek antiquity, authors titled a range of small handbooks on various subjects with the term enkheiridion, meaning en, ‘within’, one's kheir, ‘hand’.Footnote 3 The Greek term kheir for ‘hand’ remains in English today in chiromancy (palm reading), chirography (handwriting) and chiropractic (lit. hand + practical). Although one rarely sees enkheiridion (or, for that matter, its Late Latin version enchiridion) in book titles today, one still finds the Old High German hant and Old English hand in the German Handbuch, Swedish handbok and English handbook. The Latin vade mecum (or vademecum, lit. ‘go with me’) once commonly designated handbooks in early modern Europe; it also is no longer used. Now the portability that vademecum emphasized remains in the French format de poche, German Taschenbuch, and English ‘pocket-sized’ paperback editions. Based on precedents established by the German Albatross Books and British Penguin Books in the early 1930s, in fact, the new publishing house ‘American Pocket Books’ first developed cheap pocket-sized paperbacks in the late 1930s.Footnote 4 Whereas these material dimensions of book formats are called publishers’ peritexts, this paper is primarily concerned with book titles, one of many paratextual elements attached to core texts in manuscript and printed forms.Footnote 5

But such a seemingly straightforward title as ‘the handbook’ – and its cognates – can also be misleading. The multiple textual forms to which manual and handbook could refer changed over time and differed regionally. European authors and publishers used the metaphoric hand in book titles within many fields representing very different physical forms, for example, from ‘handy’ how-to guides intended to be carried on one's person to ‘at-hand’ reference books whose virtue of completeness could also make them, by contrast, rather unwieldy.Footnote 6 European literary scholars have developed a vibrant sub-field on the study of titles or titrologie that can be situated within the broader attention paid to paratexts.Footnote 7 Not only are book titles distinct from the intertitles that separate the book's constituent parts, but also titles themselves have two distinct descriptive functions – thematic and rhematic – that signal either what ‘this book talks about’ (thematic) or what ‘this book is’ (rhematic), mainly the genre form of their narrative. Furthermore, ‘connotative’ refers to the manner by which a more thematic or rhematic title denotes both what the book is about and the book's narrative form via other rhetorical strategies, such as playful homophony, clever archaism, historical allusion, and such.Footnote 8 Titles thus have distinct parts as well as functions that can be productively parsed historically and contextually. As many modern authors are well aware, publishers also complicate authorship of book titles by seeking to entice more readers with what they consider more seductive titles than their authors originally intended. What is true for the present is no less so for the past in Europe or China.

Inspired by literary scholarship on paratexts, this article focuses on just the titles of Chinese medical texts as a method to begin to address how Chinese authors/publishers attempted to communicate to potential readers the relationship between their books’ material form and contents and their intended functions, from the earliest evidence in antiquity to the fourteenth century. By paying particular attention to what terms the Chinese used to distinguish narrative forms or genres (rhematic) from topics or themes (thematic), historians can better understand what metaphors the Chinese used to convey the book's physical form as well as changes in narrative structure. As such, this article establishes groundwork for deeper analysis of the complex transformations in organizing Chinese medical knowledge over the longue durée to which these medical titles referred and about which this article presents a preliminary overview.

The easy-to-carry books and, at the other end of the spectrum, at-hand comprehensive references in the history of European publishing, for instance, also existed throughout the publishing history of imperial China. But how did Chinese authors and publishers title the former type of ‘handbooks’ and ‘manuals’ to signal to their potential readers similar qualities of accessibility, portability, concision and learning a technical subject by the book? Although portability metaphors – as in vademecum, ‘go with me’ – were also used to signal such qualities, European authors and publishers from antiquity through the early modern period preferred the hand itself as the dominant bodily metaphor in their choice of the three main textual genre terms – enchiridion, handbook and manual. Their Chinese counterparts also sometimes used the metaphoric hand to convey comparable textual qualities of distillation, accessibility and portability, but on the whole they chose very different metaphors, bodily and otherwise. These metaphors are worth exploring as integral to China's publishing history on its own terms. They also reveal how Chinese conceptualized narrative forms similarly to what the European terms for manuals, handbooks and enchiridions conveyed through different metaphors.

The closest modern Chinese equivalent term for these European-language terms is shouce 手冊 (lit. ‘hand volume’, ‘hand booklet’), which is the current Chinese translation for the English ‘manual’ and ‘handbook’. It is distinct from the older Chinese terms for ‘manuscript’ shougao 手稿 (lit. ‘hand draft’, ‘hand sketch’) or ‘hand-copied book’ (chaoben 抄本).Footnote 9 Shouce, however, did not rhematically designate any separate genre in Chinese publishing before the twentieth century. Based on extant Chinese medical texts, it only became used in that way during the late 1940s.Footnote 10 Instead we find the earliest references in titles of medical texts to the ‘hand’ first modifying mirrors in the Tang dynasty (618–907), and then rhymes in the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127). Only very late during the seventeenth century do extant medical titles contain the ‘hand’ modifying terms for ‘records’ (lu 錄), ‘methods’ (fa 法), ‘to hold’ (yuan 援), and ‘volume’ or ‘booklet’ (ce 冊).Footnote 11 These uses of the hand metaphor were exceptions, however, and did not develop into a rhematic genre term for Chinese medical primers or more specialized texts intended for ‘learning medicine by the book’ comparable to enchiridions, handbooks, or manuals in Europe.

Earliest evidence of genre titles in Chinese medicine

When did Chinese authors, editors and publishers first signal to potential readers that they could ‘learn medicine by the book’? If the hand was not the dominant metaphor over the course of imperial Chinese history as it was in Europe, then what other metaphors were used to convey comparable textual qualities? Furthermore, how did Chinese authors express that their medical books were not only physically portable but also condensed and conceptually easier to master? The remaining sections of this article present preliminary answers to these basic questions up to the early fourteenth century.Footnote 12

Conveying genre distinctions

Building further upon Genette's distinction between thematic (topic) and rhematic (genre) titling strategies, Gianna Pomata distinguished epistemic from other genres as ‘the specific kind of genres whose primary goal is not the production of meaning but the production of knowledge ’.Footnote 13 In Chinese medicine, the earliest distinctions among epistemic genres can first be found among the titles of health-related excavated textsFootnote 14 and bibliographic references from late antiquity (third century BCE–third century CE). During this period, we find evidence of eight genre distinctions within which writers formulated medical knowledge: ‘formularies’ (fang 方) listed recipes in a systematic way; ‘writings’ (shu 書) focused on a specific subject (such as channels, pulses or pulling techniques); ‘discourses’ or ‘treatises’ (lun 論) also analysed one subject (such as drugs or a class of disorders); ‘consultation records’ (zhenji 診籍)Footnote 15 contained the term for ‘records’ (ji 籍) that signified taking notes about something; ‘methods’ (fa 法) signalled an instructive how-to genre about techniques; ‘interdictions’ (jie 禁) suggested proscriptive advice on what to avoid; and whereas ‘way’ or ‘teachings’ (dao 道) indicated different intellectual genealogies, ‘canon’ (jing 經) demarcated a consensus on foundational knowledge within these genealogies.Footnote 16 The eight terms that ancient authors used to differentiate the main epistemic genres for writings about health, disease, diagnosis and treatment had remarkable continuity thereafter.Footnote 17 Later authors relied on this repertoire of genre terms for the wide-ranging metaphors they developed to convey other structural and narrative strategies of their medical texts.

In addition to the many excavated medical texts unearthed since the 1970s, the earliest evidence of actual genre distinctions is in the bibliographic section of the History of the Former Han (Han shu 漢書), the next important source for medical text titles from Han antiquity.Footnote 18 Within the new Seven Epitomes (qilüe 七略) classification system that curator Liu Xin 劉歆 (50 BCE–23 CE) used to organize the Former Han dynasty's imperial library,Footnote 19 one finds for the first time twenty-nine distinct medical titles classified into four main categories: ‘medical canons’ (yijing 醫經); ‘canonical formularies’ (jingfang 經方); ‘arts of the bedchamber’ (fangzhong 房中, lit. ‘within the bedchamber’); and ‘arts of transcendence’ (shenxian 神仙, lit. ‘divine immortals’).Footnote 20 The first two bibliographic categories contained the two rhematic terms ‘canons’ and ‘formularies’ that were modified respectively by the thematic adjectives ‘medical’ and ‘canonical’; the latter two categories, conversely, used phrases that functioned metaphorically to connote their contents such that ‘within the bedchamber’ referred to the sexual-cultivation practices often associated with the arts of guarding life (yangshang 養生) of the period,Footnote 21 and ‘divine immortals’ subsumed titles related to practices of contemporaneous cults of immortality.Footnote 22

Conveying essential knowledge

One text within the final category of ‘arts of transcendence’, however, introduced a new rhematic use of the character yao 要 that is not found in extant evidence on Han medical book titles from excavated texts or the other medical texts listed in the bibliographic section of History of the Former Han. In the title Daoyao zazi 道要雜子, the second character yao verbally means ‘to want’ or ‘to wish’ and nominally means ‘main points’ or ‘essentials’. The first character dao is one of the eight genre terms discussed above. In this title it still means ‘way’, or metaphorically ‘teachings’, but here it functioned grammatically as an adjectival modifier. Daoyao is therefore best translated as ‘essentials (yao) of the teachings (dao)’. The third character za for ‘various’ modifies the final character zi, meaning ‘masters’. The best translation for the full title is Essentials of the Teachings of the Various Masters. By the first century CE, then, Chinese scholars had been reorganizing, synthesizing and summarizing their increasingly complex medical knowledge for at least four centuries, yet this title appears to be the earliest example of a decision to communicate the narrative form of summing up the ‘essentials’ of that subject in a medical text title.

One more Han-era example used yao rhematically to indicate a distinct genre of texts characterized by selection of essential points. The scholar–physician Huangfu Mi 黃甫謐 (215–82 CE) cited in the preface to his Acupuncture A–B Canon (Zhenjiu jia-yi jing 針灸甲乙經) the title of a since-lost Han-era text on acupuncture titled the Essentials of Treatment from the Illuminated Hall's Apertures and Acupuncture (Mingtang kongxue zhenjiu zhi yao 明堂孔穴針灸治要). Placed at the end of the otherwise thematic title, the yao rhematically referred to the ‘essentials’ of medical treatments related to the apertures (kongxue, i.e. openings on the human body for targeting needling and cauterization) and acupuncture (zhenjiu, i.e. therapeutic needling). The first phrase of the title, Illuminated Hall (Mingtang), linked this medical tradition to a cosmological concept related to a theory of monarchy and thus to the communities who then supported that theory.Footnote 23

Furthermore, yao, ‘essentials’, appears in two cases – Essentials of the Way of Various Masters and Essentials of the Treatments of the Apertures and Acupuncture of the Illuminated Hall – to refer rhematically to a new textual form, providing neither all orthodox knowledge about the subject as jing, ‘canon’, conveyed, nor a clearly structured synthesis of a subject as lun, ‘treatise’, indicated. Rather these titles suggest that just the ‘essential’ or ‘main’ (yao) aspects of that subject had been distilled in narrative form.

The remaining overview of metaphors in titles of Chinese medical texts is divided into the following three periods roughly parallel with medieval Europe (500–1500): (1) the early medieval period covering the Six Dynasties (220–589) to the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties; (2) the middle medieval period covering the Northern Song (960–1127), Southern Song (1127–1278) and northern Jurchen-ruled Jin (1115–1234); and (3) the late medieval period, including Mongol Yuan (1271–1368) and the first decades of the Ming (1368–1644) dynasty. By examining the major changes in metaphors used to convey to readers what to expect in texts intended for learning medicine by the book, this article hopes to facilitate comparisons with the very different European historical record and to open up inquiry into how Chinese publishers used different metaphors to convey comparable textual forms.Footnote 24

New metaphors for new textual forms in early medieval China

Chinese medical knowledge was transmitted socially within familial and personal networks as well as through texts. Most physicians did not formally teach their knowledge in academies (xueyuan 學院), medical schools (yixue 醫學), or imperial medical bureaus (taiyiyuan 太醫院); rather they transmitted their medical knowledge and healing strategies privately through master–disciple, clan and lineage relationships,Footnote 25 and through non-familial social networks of like-minded friends and colleagues.Footnote 26 New metaphors indicating textual changes for a broader audience interested in medical knowledge began to appear later during the Six Dynasties period (220–589). In the Sui–Tang period (581–907), more extant sources provide evidence of authors experimenting with how to reorganize the growing corpus of health-related content in more clearly accessible textual forms. For one thing, yao, ‘essentials’, continued to convey summation of the main points of a subject, but many new metaphors appeared to express innovative qualities of medical books, such as their portability on the body, preservation within storage containers and retention through rhymed prose.

‘Behind the elbow’ to kerchief-box editions

The earliest Chinese reference to a type of medical text comparable to the Latin term vademecum for ‘go with me’ is attributed to the fourth-century scholar Ge Hong 葛洪 (281–341). Although most famous in the history of science for his Daoist alchemical treatise titled simply Master Who Embraces Simplicity (Baopuzi 抱朴子), he also compiled a medical text titled the Formulary for Every Emergency behind the Elbow (Zhouhou beiji fang 肘後備急方).Footnote 27 The thematic ‘every emergency’ (beiji) clearly modifies the rhematic ‘formulary’ (fang) to indicate that the author wrote it for medical crises. ‘Behind the elbow’ (zhouhou), however, is less obvious. Since zhouhou also means ‘sleeve’ it is often translated as ‘within the sleeve’, and since the metaphor's gist is bodily proximity, ‘to have on hand’ also works; but it also connotes carrying a bag over one's shoulder and thus ‘behind the elbow’ covers that interpretation. Ge Hong stated in his preface that he had created new categories to facilitate retrieval, chose readily obtained medicinals, and simplified recipes to make this formulary easier to rely on during emergencies.Footnote 28 Thus ‘behind the elbow’ captures the greater accessibility he intended through revision of narrative forms as well as the potential portability of the completed material text.

Ge also mentioned other medical titles with container metaphors. In Master Who Embraces Simplicity, he cited the Golden Chest and the Green-Blue Satchel (Jinkui Lunang 金匱綠囊) among the texts he had relied upon.Footnote 29 A satchel metaphorically captures a bag easily carried ‘behind the elbow’ on the shoulder, whereas a chest denotes where one might store more precious books for safekeeping. Later citations attribute to Ge Hong both a Golden Chest Formulary (Jinkui fang 金匱方) and a Jade Case Formulary (Yuhan fang 玉函方). Although both texts have since been lost, Northern Song imperial editors used the same metaphors for medical texts they attributed to Han physician Zhang Ji (c.150–219).Footnote 30 The metaphors for precious materials – gold and jade (as well as possibly the green-blue color) – suggest the high quality of the texts’ contents. The chest and case container metaphors similarly suggest that such texts were valued highly enough to deserve special storage boxes. The satchel metaphor, by contrast, connotes their easy portability.

A little over a century later another type of material container was used metaphorically to refer to a new form of texts written in miniature. One record provides an account that the Prince of Hengyang (r. 473–94) of the Southern Qi dynasty (479–502) ‘transcribed the Five Classics in small characters, assembled the texts into a single juan 卷,[Footnote 31] and placed it in a kerchief box’. In early medieval China, people put their head kerchiefs and other small things into an easily carried and readily available ‘kerchief box’ (jinxiang 巾箱). Since the prince had all the classics in his home library, someone asked why he had done this. He responded, ‘Storing the Five Classics in kerchief boxes makes accessing and reading them much more convenient, and, once I myself have transcribed the texts, I shall never forget them’.Footnote 32 This material object shortly thereafter came to be used metaphorically for small-print ‘kerchief-box editions’ (jinxiang ben 巾箱本). By the early twelfth century, commercial publishers were publishing such cheap palm-sized cribs for the civil service examinations that some examinees found them so dispensable that after taking their exams they threw them out.Footnote 33 By the Yuan and Ming, publishers even began to print kerchief-box editions of written-in-miniature medical texts.Footnote 34

Versifying medicine via jue, fu, and ge

Early medieval medical authors were not only trying out new textual ways of organizing medical knowledge and innovative material formats to contain them; they were also experimenting with transforming medical prose into verse. The following three terms signify the main forms of versification of medical texts during this period: jue 訣, ‘rhymed formulas’ or ‘rhymes’, were short phrases for easier memorization;Footnote 35 the longer fu 賦, ‘rhapsody’, form of verse focused in a more sustained way on one specific topic;Footnote 36 and the ge 歌, ‘song’, were catchy ‘jingles’ comparable more to the shorter jue than to the longer fu. Medieval authors used these versified narrative forms to simplify the language of the original medical classics in efforts to popularize them as well as to facilitate their memorization.

The earliest medical examples of versification appear in early medieval records and were based on the Canon of Pulses (Maijing 脈經) by Wang Shuhe 王淑和 (b. 210). As early as the Sui dynasty (581–618), sources refer to the Essential Rhymes Pulses for Life or Death (Mai sheng si yaojue 脈生死要訣) and Mr Xu's Rhymes for the New Canon on Pulses (Xushi xin maijing jue 徐氏新脈經訣).Footnote 37 One Song text even used the ‘hand’ metaphor to mean ‘convenient’, as in the one-juan Handy Rhymes for the Canon on Pulses (Maijing shoujue 脈經手訣).Footnote 38

Additional evidence of versified medical texts comes from over 438 health-related manuscripts dating from the seventh to the eleventh centuries that were discovered in the silk-road oasis towns Dunhuang and Turfan (in modern-day Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region).Footnote 39 Most of these rare manuscripts were found among the thousands of treasures preserved in a hidden library of the Buddhist Mogao Caves in modern-day Dunhuang.Footnote 40 Many of the terms for epistemic genres previously discussed also appear within this medieval medical archive, namely canon (jing), treatise (lun), formulary (fang) and method (fa). These texts also offer evidence of two additional terms – jue 訣, ‘rhymes’, in one title and fu 賦, ‘rhapsody’, in another – that signify a narrative change from prose to verse.

Sources from the Tang dynasty (618–920) preserved even more wide-ranging titles associated with a particular sub-genre of versified pulse lore that became known as ‘pulse rhymes’ (maijue 脈訣).Footnote 41 The earliest extant version of such rhymed pulse-taking texts is the rare Dunhuang manuscript dated to the sixth century CE titled Master Qingwu's Pulse Rhymes (Qingwuzi maijue 青烏子脈訣).Footnote 42 A later version titled Pulse Rhymes and Rhapsodies (Maijue fu 脈訣賦) included the rhematic term fu that appears to specify that rhapsodies had been added to the earlier rhymed jue interpretations of the Canon of Pulses.Footnote 43 The second Dunhuang manuscript has a more thematic title, Rhapsody on the Grand Felicity of Pleasure of the Union of Heaven–Earth and Yin–Yang (Tiandi yinyang jiaohuan dale fu 天地陰陽交歡大樂賦). Nonetheless, this manuscript ends with the rhematic fu term indicating that the ancient rhapsody verse form was also used to summarize ‘arts of the bedchamber’ literature.

By the early tenth century, some medical book titles started to use ge, ‘song’, to signify another form of versification. We see this in the Songs and Rhymes on Life and Death (Sheng si ge jue 生死歌訣) and Songs for Understanding Syndromes (Liao zheng ge 了證歌) attributed to the late Tang scholar Du Guangting 杜光庭 (c.850–933).Footnote 44 To sum up, between the sixth and early tenth centuries there is evidence of three rhematic terms for versified narrative forms – jue, fu, and ge – of medical knowledge ranging from pulse taking and sexual-cultivation arts to discerning syndromes and determining cases of either life or death. During the eleventh century, new titles of publications that contained versified mathematical algorithms and problems also appeared in extant sources.Footnote 45 This evidence demonstrates that in the late medieval period there was a broader strategy of versifying text to facilitate learning mathematics as well as medicine by the book.

Extracting essentials and publishing secrets

During the same period when medical authors were experimenting with versifying health-related materials as well as mathematical texts, we also find them continuing the process of simplifying texts for easier use found earlier with Ge Hong's Formulary for Every Emergency under the Elbow. Two Tang physicians represent this trend: Sun Simiao 孫思邈 (c.581–682) and Wang Tao 王燾 (c.690–756). By using the adjectival phrase beiji, Sun directly referenced Ge's work in Essential Formulas Worth a Thousand in Gold for Every Emergency (Beiji qianjin yaofang 備急千金要方, completed before 659).Footnote 46 Instead of highlighting portability, as Ge did with ‘behind the elbow’ (zhouhou), however, Sun promoted the value of human life as worth a ‘thousand in gold’ (qianjin). He also reused the metaphor ‘essentials’ (yao) of formulas required in emergencies to save those same lives.

Wang Tao expressed similar intentions with Formulary of Secrets and Essentials from the Outer Censor (Waitai miyao 外台秘要, 751).Footnote 47 The added mi, ‘secrets’, suggests that he made previously secret medical knowledge within the imperium newly public. This choice may have come from the stressful circumstances of travelling to the south for an official post during which he came to conceptualize gathering material for this medical compilation. He encountered many travellers along the way who suffered from illnesses but recorded that they could not recover based on the medical texts they had available to them to consult.Footnote 48 Although neither Sun nor Wang actually made their formularies easily portable or ‘handy’ – thirty juan for Sun and forty juan for Wang compared to Ge's three-juan formulary – they both used new knowledge-management techniques to improve their formularies as ‘at-hand’ reference books.Footnote 49

Song medical patronage for laypeople and one physician's response

Imperial patronage of materia medica began during the Tang dynasty with five imperially patronized medical texts. Starting in the late tenth century through the early twelfth century, the Song imperial court continued Tang precedents to publish medical texts. Their new intentions of medical governance through standardization, rectification and distribution contributed to an unprecedented intensity of publications resulting in a total of thirty-eight medical texts. Many of these medical texts reflected efforts to reach a wider populace through simplified textual forms.Footnote 50 Individual physicians responded to these imperially sponsored texts in several ways. They continued summing up the essential points and versifying for easier retention, but in order to illustrate better how such texts could be applied in practice they also newly added their own clinical observations via case records.

Essentializing formulas, versifying Cold Damage, discoursing on cases

In response to people dying from epidemics, for example, the Renzong emperor in 1051 ordered imperial physician Zhou Ying 周應 (n.d.) to select the most important effective formulas in the Imperial Grace Formulary (Taiping shenghui fang 太平聖惠方, 992) and summarize them in forms more easily accessed by readers.Footnote 51 The title of the resulting Formulary Simplified and Essentialized to Relieve the Masses (Jianyao jizhong fang 簡要濟眾方, 1051) emphasized concision, extraction of essentials, and benefit for ordinary people.Footnote 52 By the mid-eleventh century, Song emperors attempted to reach a wider public by standardizing the form and expanding the contents of medical texts, on the one hand, as well as making them more accessible and concise, on the other. They also patronized a new Bureau for Revising Medical Texts that published ten medical texts over twelve years (1057–1069).Footnote 53

Privately practising physicians quickly responded to these official medical texts by transforming them into verse form. Not long after this bureau published in 1065 the first official version of the second-century Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders, for example, the physician Xu Shuwei 許叔微 (1079–1154) put its prose into verse in Songs for One Hundred Manifestations of Cold Damage (Shanghan baizheng ge 傷寒百證歌, 1132).Footnote 54 In five chapters, each consisting of verses for twenty manifestations of Cold Damage (one hundred in total), Xu sought ‘to make it easier for physicians to study and memorize it’.Footnote 55 He thereby also completed what might have been one of the first rhymed versions of the Cold Damage Treatise.

He did not stop there. Xu adeptly chose the ‘discourses’ (lun) narrative form within which the Cold Damage Treatise (also lun) was originally written, for two of his own Cold Damage compilations. In his second book, Discourses on the Subtleties of Cold Damage Revealed (Shanghan fa wei lun 傷寒發微論, 1132), for instance, the lun as epistemic genre proved flexible enough for him to record both his commentary on the Cold Damage Treatise and his own clinical observations of pathogenesis and appropriate treatment of Cold Damage.Footnote 56 His third book, Ninety Discourses on Cold Damage (Shanghan jiushi lun 傷寒九十論, 1132), expanded the rhematic lun term to include now ninety medical case histories (an 案) of Cold Damage from his own clinical practice.Footnote 57

These few examples show authors transforming Chinese medical prose into rhymed formulas, rhapsodies and songs up through the eleventh century. Furthermore, by at least the first half of the twelfth century, medical ‘discourses’ could now include medical case narratives based on a practitioner's clinical observations. These late medieval medical texts exemplify the broader efforts to facilitate learning medicine by the book through, for example, further simplification, summing up essential points, versifying for easier memorization, and newly expanding the ‘discourses’ genre to include medical cases, all of which continued thereafter.

Bodily metaphors in late medieval medical texts

The imperial patronage of medical texts peaked with the new Medical Bureau for Revising Medical Texts (active 1057–69).Footnote 58 The Song imperium mainly patronized materia medica, formularies and clinical works (especially the Treatise on Cold Damage). Within these genres, the editors consciously reformulated many of them for easier reference, ready use and broader distribution.Footnote 59 These imperially published medical canons, formularies, materia medica and clinically oriented treatises provided the foundation for establishing a new medical scholarly orthodoxy during the following two foreign-ruled Jurchen Jin (1115–1234) and Mongol Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties.Footnote 60

Along with wider access to medical knowledge that woodblock publishing made newly possible, fundamental social transformations were occurring during this Song–Jin–Yuan transition period – including the rise in population, spread in literacy and relative levelling of degree quotas. These transformations furthermore contributed to refashioning medicine as a newly respectable alternative to an official career.Footnote 61

Commercial publishers in Jianyang, Fujian Province, for example, started to meet the new demand by publishing some medical texts during the Song. By the Ming, they were publishing more on medicine than on any other subject, followed closely by encyclopedias and then classics.Footnote 62 With the sharp growth in publishing, related rise in general literacy and greater availability of printed popular books for novice learners during the Ming, it became more possible for literate Chinese to learn medicine through books rather than primarily through discipleship or within hereditary lineages. By the seventeenth century, publishers in Anhui Province's wealthy Huizhou region began to issue self-sufficient medical handbooks and comprehensive textbooks tailored to the interests of ‘a new readership of unemployed licentiates and upwardly mobile young men’.Footnote 63 New metaphors thus matched new forms of medical texts, including ‘mirrors’ (jian 鑑, jing 鏡) and the ‘heart–mind’ (xin 心), ‘heart–mind mirrors’ (xinjian 心鑑), ‘handheld mirrors’ (shoujing 手鏡, shoujian 手鑑), and even ‘handy rhymes’ (shoujue 手訣). Parts of the hand, such as the palm and fingers, also began to feature as metaphors for knowledge and mastery.

South-pointing guidebooks and pointing to one's palm

Whereas the heart–mind metaphor emerged as meaningful for learning medicine by the book within the broader context of Song Neo-Confucianism, other medical texts of the same period used zhi 指, meaning ‘finger’ or ‘to point’, as a new bodily metaphor in two phrases that also acquired rhematic meaning. The first was zhinan 指南 (lit. ‘finger and south’ or ‘pointing south’), which when combined with the character for yu 魚 (‘fish’) formed the phrase ‘south-pointing fish’ (zhinan zhen 指南魚). Today this is identified as the magnetic compass.Footnote 64 A compendium of military technology finished in 1044 described for the first time a floating fish-shaped iron object that moved freely in water such that, no matter how the ship moved at sea, the fish head pointed south.Footnote 65 This new early eleventh-century maritime use of magnetic compasses in China likely inspired the later rhematic meaning of ‘pointing south’ in the publishing realm. By the mid-thirteenth-century, at least two medical titles used ‘pointing south’ to signify a new genre intended to orient the reader through a specific medical subject: South-Pointing [Compass] for the Needling Canon (Zhenjing zhinan 針經指南, 1232) and South-Pointing [Compass] for Examining Disease (Chabing zhinan 察病指南, 1241).Footnote 66 These two titles signalled that their contents reliably oriented readers in a medical subject similar to how the latest technology of the ‘south-pointing fish’ compass helped navigate users in geographic space.

The second important phrase that used ‘finger’ (zhi) was zhizhang 指掌. This phrase means nominally ‘fingers and palms’ and verbally ‘to indicate, show, or point to [one's] palm’. Instead of zhinan as ‘compass’ guiding one through a subject, however, zhizhang as ‘pointing to the palm’, or ‘in the palm of the hand’, came to mean mastery of it. The locus classicus of the phrase is in the Confucian Analects: ‘Someone asked the meaning of the great sacrifice. The Master said: “I do not know. He who knew its meaning would find it as easy to govern the empire as to look on this”– pointing to his palm (zhi qi zhang 指其掌)’.Footnote 67 This same association also was made in the Song Dynastic History (Songshi 宋史) in a preface to ‘Learning-of-the-Way Biographies’ (Daoxue zhuan 道學傳) about the Song philosopher Zhou Dunyi 周敦頤 (1017–73): ‘Zhou Dunyi wrote the Explanation of the Great Unity and Tongshu; [he] was someone who expounded upon the principles of yin–yang and the five agents, celestial fate and human nature, understanding [these subjects] like pointing to [his own] palm’.Footnote 68

This short anecdote sums up well the meaning of the Chinese expression ‘to understand as if pointing to [one's] palm’ (liao ruo zhizhang 瞭若指掌). The English equivalent is ‘to know something like the palm (or the back) of one's hand’ and French savoir une chose sur le bout des doigts (‘to know something on one's fingertips’). When the tonal system does not suffice, Chinese speakers often clarify what character they mean by using their right pointer finger to draw the character within their left palm. To know something like ‘pointing to one's palm’ is not only comparable to writing from memory a character in one's hand, but a common Chinese metaphor for mastery of a subject. Instead of hand metaphors, however, most English equivalents to convey comparable meanings of mastery tend to use orientational metaphors, such as to know something inside and out, backwards and forwards, or top to bottom.Footnote 69

One of the earliest uses of zhizhang in a title to mean knowledge mastery is in the late twelfth-century rime table Phonology [as if] Pointing to [One's] Palm, with Illustrations (Qieyun zhizhang tu 切韻指掌圖).Footnote 70 The more idiomatic English translation is Phonology in the Palm of the Hand, with Illustrations. This book explained the phonological system of an earlier ‘rime book’ (yunshu 韻書) titled the Qieyun 切韻 (with a preface dated to 601). The method of Chinese lexicography called fanqie 反切 was used, wherein two characters clarify how to pronounce a monosyllabic character: the first indicated the initial consonant of the syllable and the second its final sound. Organized according to final tones and sounds, scholars used rime books as guides to properly read classical texts and poets used them as aids to write verse. Although ‘as if pointing to one's palm’ metaphorically promised mastery of phonology, this rime book also contained two ‘pointing-to-the-palm diagrams’ (zhizhang zhi tu 指掌之圖). One of the hand diagrams had characters for the thirty-six phonetic initials written on them. Readers could memorize the fanqie system by using their own hands mnemonically.Footnote 71

Some medical texts attributed to the famous physician Li Gao 李杲 (1180–1251), as well as Zhu Zhenheng 朱震亨 (1282–1358), used this metaphor of ‘pointing to one's palm’ for mastery of medical knowledge. Writings on Pulse Rhymes in the Palm of the Hand (Maijue zhizhang shu 脈訣指掌書, c.1248), used the popularizing textual forms of writings (shu), rhymes (jue) and illustrations (tu) to help readers master pulse taking.Footnote 72 The following combination of two book titles reads even more like an advertising blurb: Satchel of Genuine Pearls in the Palm of the Hand, Supplemented with Rhapsodies on Drug Traits (Zhenzhu nang zhizhang buyi yaoxingfu 珍珠囊指掌補遺藥性賦).Footnote 73 The choice to combine the metaphor of ‘pointing to one's palm’ for mastery with those for the book as a ‘satchel’ (nang) and its contents as ‘genuine pearls’ (zhenzhu) may well have attracted readers interested in learning medicine by the book. Providing the Rhapsodies on Drug Traits as supplementary material probably did not hurt sales either.

New editions of the Cold Damage Treatise – dated to the Song and Yuan periods but published in the Ming – also used this same metaphor in long titles specifying the narrative styles contained within each book: Classified and Edited Cold Damage [Treatise] to Save Lives Including in the Palm of the Hand, Illustrations, and Discourses (Leibian shanghan huoren shu kuo zhizhang tu lun 類編傷寒活人書括指掌圖論, 1564).Footnote 74 With ‘classified’ (lei) and ‘edited’ (bian) text, including ‘illustrations’ (tu) and ‘discourses’ (lun), this promised to be a cutting-edge version of the Cold Damage Treatise. An updated version kept the illustrations but changed discourses for ‘songs’ (ge) in the title: Cold Damage [Treatise], Illustrated with Songs to Save Lives in the Palm of the Hand (Shanghan tu ge huoren zhizhang 傷寒圖歌活人指掌, 1600).Footnote 75 The eleventh-century physician Xu Shuwei's earlier versification of the Cold Damage Treatise clearly remained a selling point in sixteenth-century book markets for those who sought to master its contents.

Learning medicine by the book in the Ming

What medical books can be considered handbooks for Chinese medicine in roughly the first millennium of imperial Chinese history? How were such books titled to indicate their handbook quality and convey that their contents had been condensed, reorganized, versified and illustrated? This article has charted a preliminary path toward answering these questions related to learning medicine by the book up to the mid-fourteenth century. Medical texts suggested more accessible ‘handbook’ structures with titles that referenced summarizing the essentials (yao), mirroring reality (jing, jian), versifying prose (jue, fu, ge) and bodily metaphors, such as behind the elbows (zhouhou), handheld mirrors (shoujian, shoujing), the heart–mind (xin), pointing south (zhinan) and pointing to the palm (zhizhang). Some of these metaphors signalled the ‘handy’, portable and ‘in-one's-hand’ quality of the material book while others emphasized orienting readers or their potential mastery of its content. This overview of the main metaphors that conveyed various strategies to facilitate learning medicine by the book demonstrates that there were many innovative approaches to formulating, managing and popularizing the increasingly complex medical knowledge in China from antiquity through the late medieval period.

Based on the foundation of this vast medical archive, self-identified medical primers arguably first appeared in book markets by the end of the fourteenth century.Footnote 76 Liu Chun 劉純 (c.1340–1412), the son of one of Zhu Zhenheng's disciples, not only continued his predecessors’ versification strategy in Materia Medica in Songs and Rhymes (Bencao gejue 本草歌訣) and Rhymes on the Nature of Drugs (Yaoxing fu 藥性賦), but also published a Primary Study on the Medical Canons (Yijing xiaoxue 醫經小學, 1388). Although previous authors published medical primers, one scholar has argued that this was possibly the first self-identified and systematic medical textbook.Footnote 77 Liu Chun also summed up the previous Jin–Yuan period's scholarly medical orthodoxyFootnote 78 by putting into rhyme essential knowledge that then constituted classical Chinese medicine.Footnote 79

To appeal to an expanding audience ranging from medical novices to literate physicians, early Ming medical authors continued using previous metaphors of portability, concision and ease of use, and created new ones. Within five years of Liu Chun publishing his medical primer, another way to express the comparable Latin vademecum for ‘go with me’ appears in the following two collections: Great Complete Formulary of Treasures Tucked Inside a Sleeve (Xiuzhen fang daquan 袖珍方大全, 1390) and Writings and Formulary of the Simplified and Selected Treasures Tucked Inside a Sleeve about Pediatrics (Jianxuan xiuzhen xiaoer fangshu 簡選袖珍小兒方書, pub. 1391).Footnote 80 Like the ‘behind-the-elbow’ formularies and ‘kerchief-box’ editions from early medieval China, this new clothing metaphor of the late fourteenth century conveyed that, in addition to being simplified, selective and full of treasures, these ‘sleeve-sized’ books could be carried within one's clothes.

From hand metaphors to mnemonic hands

During the Ming dynasty, the range of metaphors utilized in titles to signal the ‘handbook’ qualities of medical texts considerably expanded. The character for ‘hands’ (shou) reappears in several seventeenth-century medical texts but it was rare and not used rhematically comparable to the manuals, handbooks and enchiridions of Europe.Footnote 81 Even when medical publishing developed during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the hand was not as commonly used as the two phrases ‘south-pointing’ (zhinan) and ‘pointing to one's palm’ or ‘in the palm of the hand’ (zhizhang) first used during the Song period.

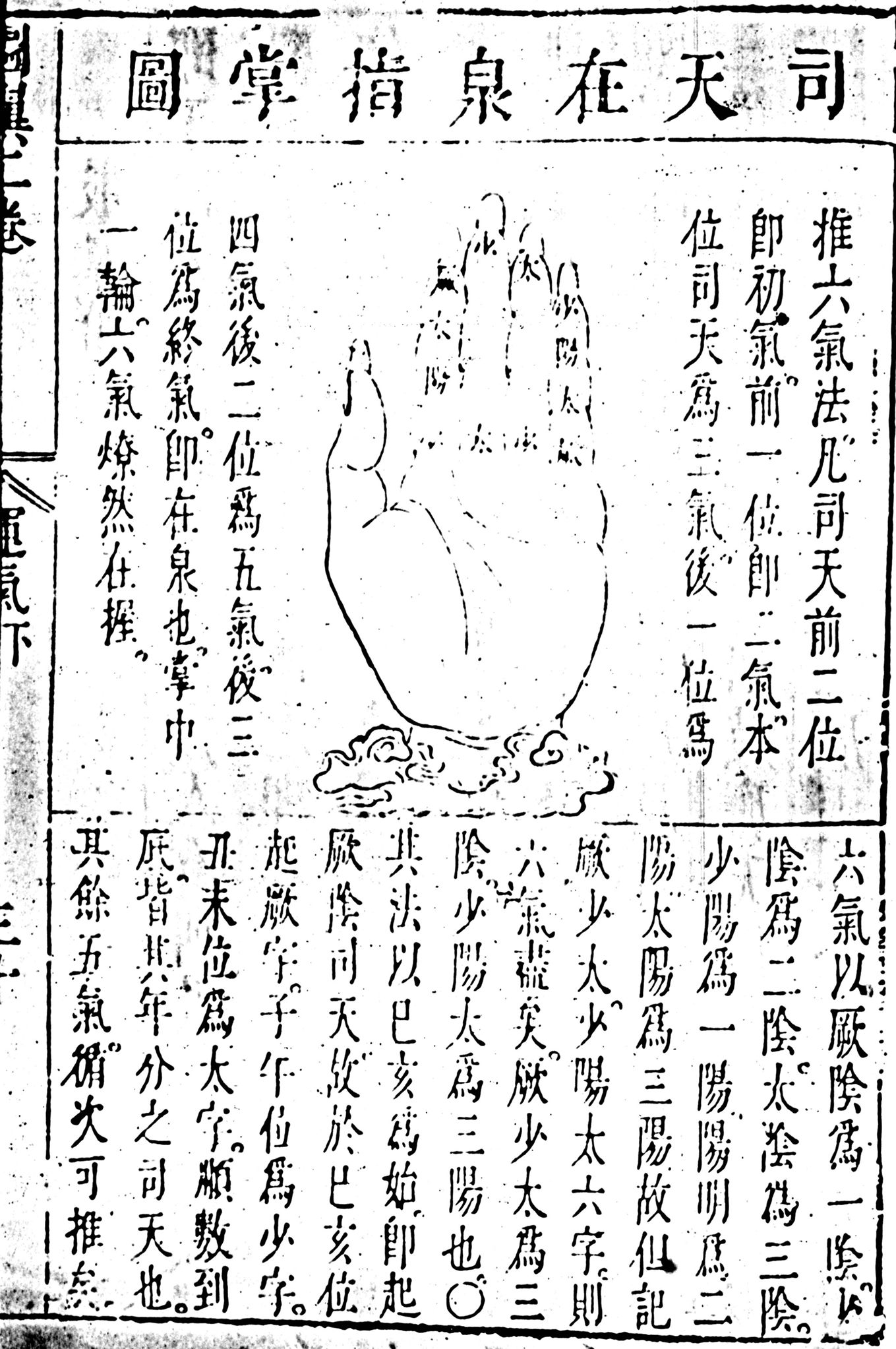

The Chinese metaphors of orienting with a ‘south-pointing’ compass and, especially, mastery through ‘pointing to one's palm’, likely resonated with the widespread practice of hand mnemonics in Chinese culture.Footnote 82 This preference in Chinese medical texts for fingers and palms over the hand itself in rhematic categories arguably corresponds also to interpretations of hands as a microcosm of the world. One illustration of this analogical thinking is in a late Ming medical text titled the Classified [Inner] Canon, Illustrated with Commentary (Leijing tu yi 類經圖翼) by the scholar–physician Zhang Jiebin 張介賓 (1563–1640). Zhang wrote an essay that accompanied two hand mnemonics titled simply ‘Explanation of pointing to the palm’ (Zhizhang jie 指掌解). The essay not only explained the two hand mnemonics as bodily means for legitimating medical doctrines, but also mapped spatio-temporal units onto the fingers’ articulations as well as the human body (Figure 1). The opening lines of the essay that establish the fingers and palms as correlates with Heaven and Earth give a sense of this kind of macro–microcosm reasoning:

Heaven has four seasons, Earth has four directions, Man has four limbs. With the joints of the fingers, one observes Heaven; with the lines of the palms, one examines Earth. The patterns of Heaven and Earth are completely within the palms.Footnote 83

Figure 1. ‘Diagram of govern-Heaven and in-the-source hand mnemonic’, in Zhang Jiebin 張介賓 (1563–1640), Classified [Inner] Canon, with Illustrations and Commentary (Leijing tu yi 類經圖翼), 1624 first edition, Rare Books Collection, National Central Library, Taiwan. The twelve positions divide annual seasonal change into six steps; the surrounding text explains where to find each step on the fingers, concluding, ‘With one revolution in the palm, understanding the six qi is within one's grasp’.

Zhang Jiebin's 1624 essay on the ‘Explanation of pointing to the palm’ thus suggests a more philosophical reason why human fingers and palms were used as metaphors both rhematically, for a genre of medical texts comparable to Western ‘handbooks’ or ‘manuals’, and figuratively, for the conception of mastery of the knowledge they contained. The Chinese conception that human hands were microcosms of the same spatial–temporal order of Heaven and Earth that aspiring healers were expected to master influenced this different use of the finger-pointing metaphor in Chinese compared to the hand metaphor in European book culture. Aspiring healers sought to fully grasp corporeally as well as conceptually the knowledge of Heaven and Earth directly related to health, illness and healing. They could do this on their own through these new handy forms of medical text, carried in satchels that hung just below their elbows, stored as if treasures in their chests and cases, tucked into their sleeves, recited through various forms of verse, held in their hands as if mirrors of reality, used as if an orienting compass, and memorized to the point of their mastery.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship, which supported a leave while I completed this article. I also wish to thank the editors of this volume for including my research in the collection and for their patient prodding through revisions. My department colleagues Gianna Pomata and Dan Todes gave me valuable feedback and timely advice on analysing metaphors in science. I also received helpful comments from colleagues participating in workshops for the project and in seminars at the Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS). Two anonymous reviewers considerably improved a much earlier version of the manuscript, for which I remain gratefully indebted.