Introduction

In January 1938, Jane Dabney Shackelford, an African American schoolteacher from Terre Haute, Indiana, published The Child's Story of the Negro. The book followed a sweeping historical arc. It started with traditional African society, moved to slavery, and finally turned to Black achievement post-emancipation. What set the book apart was not its historical narrative, however, but Shackelford's effort to tailor Black history to young children's cognitive development. Written in simple prose and packed with illustrations, her book was designed to spur her young readers’ imagination of what it meant to be Black, not just in America but across the diaspora. It was, according to Shackelford's introduction, meant to meet “a long-felt need” to have materials that teach Black children to “appreciate the traditions, aspirations, and achievements of the Negro race.”Footnote 1

Between the First and Second World War teachers like Shackelford had begun to respond to this “long-felt need.” Indeed, her book was part of a curricular movement affiliated with Carter G. Woodson's Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH). Woodson served as the public face of Black curricular reform in the United States during the period.Footnote 2 By the mid-1930s, he had established and popularized Negro History Week (now Black History Month), written an impressive catalogue of Black history textbooks, and developed a stinging critique of American public education, arguing that it operated as a form of “miseducation” for African American children.Footnote 3 Black teachers like Shackelford were inspired by Woodson's public advocacy and quickly joined the ranks of the ASNLH. As they did, they produced new educational outlets for representing a collective racial history, culture, and ultimately, identity in their classrooms.Footnote 4 Children's literature, such as works like The Child's Story of the Negro, was an important part of this effort. While it was not the only pedagogical form to emerge from the ranks of ASNLH-affiliated teachers, among Black elementary teachers—who comprised close to 90 percent of the African American teaching force in the late 1930s—curriculum adapted to young children's development held special importance.Footnote 5

This article examines how two Black teachers, Helen Adele Whiting and Jane Dabney Shackelford, used children's literature as a means of constructing Black identity. I argue that children's literature served as a vehicle for producing racial identity, not merely representing it. In making this claim, I turn to the work of Whiting and Shackelford, both African American women who spent their careers as educators in segregated elementary schools. I position them as simultaneously exceptional and reflective of a broader social movement during the interwar period. What made them exceptional, of course, was their status as published authors: Whiting and Shackelford were among a very select group of African American educators who wrote and published children's literature during the first half of the twentieth century.Footnote 6 Yet even as they gained a rare level of public notoriety, their work reflected a widespread belief among Black educators of that era—that students’ racial needs should guide curricular reform, and that Black teachers could produce affirming narratives of Black experiences that aligned with classroom practice. Although Woodson and the ASNLH served as an important catalyst for this belief, it is helpful to move beyond this immediate context and examine Black teachers’ work in the cultural milieu of the Harlem Renaissance, or what contemporaries called the “New Negro movement.”

During the 1920s, African Americans began a public conversation on racial identity, examining new ways for Blackness to be imagined, constructed, and disseminated to shape public consciousness. Black intellectuals, artists, and activists began to explore the race's connection to Africa and the political bonds that tied people of color together.Footnote 7 Teachers had participated in the New Negro movement since its inception, particularly as writers and artists. As the movement waned in the 1930s, a growing number of Black educators found ways to enter this cultural dialogue using the medium they knew best: teaching.

Even while teachers took up the challenge of representing their race in children's literature, they were confronted by the fact that cultural and racial identity has never been a stable or fixed phenomenon. This is a key insight of the field of cultural studies: racial identities are constantly being produced (and contested) through discourses, markets, and social institutions.Footnote 8 Since the early nineteenth century, intertwined discourses growing out of notions of social progress, national identity, and Christian morality had been explicitly racialized—they were imagined as the sole domain of White people. Likewise, Blackness was made to represent barbarism, thus justifying the enslavement of African people and Western colonial conquest. Advocates for a New Negro were seeking to contest this interpretation through a new discursive framework of global Blackness. Their goal was to create counternarratives to remove the stigma of inferiority, and position Black identity as a basis for political and cultural unity.

This paper highlights the pivotal role of teachers Helen Adele Whiting and Jane Dabney Shackelford in this widespread and diffuse cultural movement. African American teachers were not simply passive recipients of an outside Black culture or only looking to implement others’ educational materials, but rather were intellectual actors involved in the production and contestation of racial identity during the interwar period. This fact comes through in several historical studies of Black teachers. For example, LaGarrett King, writing about history textbooks produced by Black educators between 1890 and 1940, argues that their texts “were not simply neutral or independent projects at expanding African-American historic representation, but were also connected to a larger purpose that attempted to alter the racial meanings associated with Blackness.”Footnote 9 Scholar Alana D. Murray frames these Black history texts and similar efforts—including pageants written by African American educator Nannie Burroughs and performed by her students—an “alternative Black curriculum.”Footnote 10 Adopting this framework, historian of education Michael Hines shines a light on Madeline Morgan, an African American teacher in Chicago who created a robust Black studies curriculum that was adopted in public schools citywide during World War II.Footnote 11 These examples show Black teachers invested in developing curriculum and cultural theory throughout the first part of the twentieth century. Indeed, they believed that school could serve an essential role in the ongoing discourse on identity and, using their pedagogical skills, sought to align Black representation with the learning needs of African American students.

My examination of children's literature produced by Black teachers makes several important scholarly contributions. First, while scholars have considered the importance of textbooks and, to a lesser extent, children's literature written for Black students during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, teachers have been largely left out of the picture.Footnote 12 As a result, even as curricula and other education materials are recognized as contributing to the cultural milieu of the period, a top-down view of cultural production remains the norm in the historiography: interpretation and representation of the social world is produced by a class of intellectuals—professors, writers, and artists—while teachers simply pass this along to their students. Second, while I acknowledge the important role Woodson played in supporting Black children's books by teachers, I look beyond Woodson to position Black educators as cultural participants in the New Negro movement.Footnote 13 From this view, children's literature created by teachers ought to be viewed as a part of the movement's cultural discourse on race and identity.Footnote 14

Finally, by adopting theories of racialization, this article provides a model for histories of education documenting the proliferation of curriculum materials with an explicit focus on racialized histories and culture. Whiting and Shackelford were not only using the curriculum to contest the intellectual underpinnings of Jim Crow and disrupt narratives of Black inferiority, they were also trying to discursively construct a vision of Blackness for their students. This was not merely a liberal campaign of curricular diversity and inclusion. Instead, it was an effort at Black self-definition—a project that found its way into most aspects of African American public culture during the period, and in which schools and teachers likely played a pivotal, yet understudied, role. A deeper understanding of the history of Black teachers’ curricular struggle for self-definition provides a particular salience in our current moment. As many educators are seeking to take up the banner of anti-racist education, this history offers a helpful reminder that curriculum materials—including children's books—hold the potential to shape racial identity and racialization. In other words, curriculum does not just reflect culture and identity, it creates it.

To begin this article, I first consider theories of racialization that have emerged in the field of cultural studies. This provides a theoretical lens that informs my framing of the New Negro movement and The Brownies’ Book, one of the earliest periodicals produced for African American children. From there, I lay the groundwork for understanding children's literature produced by African American teachers by framing it as an outgrowth of early science on childhood development and educators’ interest in the curricular potential of Africa. In the final two sections I examine children's books written by Helen Adele Whiting and Jane Dabney Shackelford.

Theorizing Racial Representation and Black Identity

It has become mundane to note that race is a social construction, lacking any basis in science, but this point is more often repeated than understood. Part of the problem stems from the fact that the way we talk about race leaves the process of racialization undetected. Cultural theorists and scholars of race have argued that society naturalizes race (and racial identity) in ways that make conceptions of “White” and “Black” appear fixed and the process of racialization unintelligible. For example, scholars Karen Fields and Barbara Fields call the process by which racialization becomes invisible, leaving only race in its wake, “racecraft.” “Like six o'clock,” Fields and Fields note, race is at once both an idea and social reality, produced through “the ordinary course of everyday doing”—social relations, institutional rules, discourses, and rituals.Footnote 15 Similarly, Michael Omi and Howard Winant propose “racial formation” as a conceptual framework, emphasizing the ways in which racialization occurs at almost every level of society, from interpersonal interactions to state policy.Footnote 16 For Fields and Fields, and Omi and Winant, race is not a neutral category of difference, but rather an ideology that forms a basic organizing principle of society, premised on notions of insider and outsiders, superior and inferior, and even human and subhuman. They contend that White supremacy is less the domain of individual racists than social and cultural practices baked into racialization.

Knowledge production—and its dissemination in the form of teaching—is not exempt from the processes of racialization. Stuart Hall points out that Blackness has long been positioned as the “Other” within Western epistemology.Footnote 17 This is apparent in the historical discourse on civilization, which defined “civilized” culture by standards of European and Anglo-American societies and positioned this as standing in contrast to an imagined Black or African “barbarism.” But for Hall what is notable is the way Black people have become subjected to this view. “[The West] had the power to make us see and experience ourselves as ‘Other,’” he notes. A “regime of representation” is not only imposed on minoritized peoples to justify racial hierarchies, but it becomes an “inner compulsion,” as Hall puts it.Footnote 18 For this reason, Black Americans (along with other minoritized groups) have often experienced themselves through frameworks of difference—as social outsiders, ahistorical, and inferior. W. E. B. Du Bois famously characterized this experience as a kind of “double consciousness”: a “sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”Footnote 19

This core aspect of racialization has spurred a variety of responses from Black Americans, not the least of which is Black cultural nationalism. During the time that Du Bois wrote about “double consciousness” in Souls of Black Folk, for example, he also led the American Negro Academy—an organization with the mission of promoting what members considered a distinctive Black cultural and scholarly contribution to civilization.Footnote 20 The activities of the American Negro Academy were a form of “self-racialization.” “It should . . . be borne in mind that attaching meaning to one's own group as a ‘race,’ and instill[ing] this meaning with positive attributes,” the theorist Steve Garner notes, “is a common practice for subordinate groups seeking to defend and assert themselves collectively.”Footnote 21 Hall's notion of a racial “regime of representation” suggests such a possibility. To a significant extent, the cultural meaning linked to racial categories (often various conceptions of superiority and inferiority) grows out of forms of representation. For Hall, this means racial identity is not “an already accomplished fact”—some set of fixed qualities that can be discovered—but rather a process that is “never complete” and “always constituted within, not outside, representation.”Footnote 22 As an identity, “Black” was an act of interpolation—a discourse promoted by a White ruling class seeking to construct a fictive sameness among poor, but free, Whites and differentiate them from Africans in bondage.Footnote 23 But that meaning has never been fixed in time and space. Through various efforts toward Black self-determination the very idea of “Black” has been a site of contestation. Black communities throughout the diaspora have often blended myths, symbols, cultural narratives, and historical discourses as they sought to define race on their own terms. By its very nature, fashioning a new Black identity has been a collective and public project among people of African descent. As Hall helpfully suggests, “Black is an identity which had to be learned [emphasis added].”Footnote 24

But who teaches Black identity? What does the “curriculum” for an alternative regime of representation—one that affirms Blackness—look like? And how would childhood shape the way Blackness is constructed and taught? The first work of children's literature to seriously tackle these questions was The Brownies’ Book, a periodical written for African American children in the early 1920s. In the next section, I consider The Brownies’ Book and the larger New Negro movement that inspired the periodical.

Constructing a “New Negro” in Black Public Culture and The Brownies’ Book

During the 1920s, the Harlem Renaissance pushed questions of representation to the forefront of Black public life. Among the advocates of the New Negro movement—or the “New Negro Renaissance”—the problem with mainstream depictions of Blackness were apparent. By the 1890s, the Reconstruction-era promise of African American inclusion into the nation's body politic had faded away. In its wake was a system of second-class citizenship, built on underfunded public schools, segregated housing, and a restrictive labor market. The structural components of Jim Crow were propped up by a culture that portrayed slavery as benign and African Americans as unfit for self-governance. White historian Hubert Howe Bancroft expressed this view in 1912 when he declared “the Negro . . . a pathetic picture”:

However learned he may become, however lofty his ideals or high his aspirations, he must wear the badge of ignorance and servitude, he and his children forever. God hath made him so; man has re-stamped him; time brings no relief. It was a cruel kindness to enslave him; it was cruelty pure and simple to enfranchise him.Footnote 25

To many African Americans, such views undergirded the political and economic repression they faced. The inevitable conclusion, as Pan-Africanist scholar John E. Bruce put it in 1914, was that “the battle of the darker races is an intellectual one.”Footnote 26

The politics of racial identity were evident in Bruce's declaration of intellectual warfare. Rather than seek to portray the diverse experiences of people of African descent, Bruce and other advocates for the New Negro movement wanted to reframe Black identity. This was not an original campaign. Even during enslavement, African Americans produced their own counternarratives—focused, for example, on enslaved people who ran away or debunking racist pseudo-science—but the New Negro movement of the 1920s elevated this project, buoyed by mass migration of African Americans into southern and northern cities and a growing consumer market for cultural products. Historian Davarian Baldwin points out that New Negro discourse was created in large part by an expanding marketplace: “The worlds of race papers, race records, race films, and race entrepreneurship were essential spheres where cultural producers, critics, and patrons engaged the arena of commercial exchange to rethink the established parameters of community, progress, and freedom.”Footnote 27 Yet, the movement (and its marketplace) was neither unified nor particularly cohesive. Throughout the 1920s, the term “the New Negro” was invoked so often, and by such a diverse range of Black intellectuals and political leaders, that it operated as a floating signifier, defined more by what it stood in opposition to (i.e., Black people as subhuman) than any particular conception of Blackness.Footnote 28

Of course, themes emerged. One area of focus was histories of “representatives of the race”—distinguished Black men (and the occasional woman) whose achievements were used as evidence of the race's national and international contributions.Footnote 29 Likewise, classical African civilizations such as Egypt and Ethiopia, which had been an interest among Black scholars since the late nineteenth century, took on a larger role in the public imagination as African Americans sought to challenge the idea that Black people represented the lowest rung of civilization.Footnote 30 Perhaps the most distinctive thematic concern of the period was the effort to represent and affirm a distinctly Black culture and frame it as a diasporic inheritance. This was apparent in the work of Harlem painter Aaron Douglas, who explored African cultural motifs in his modernist art. Similarly, writer and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston adopted southern “folk” dialect as she sought to represent rural Black culture in her novels. Her approach offered what some critics considered an “authentic” portrait of Black life (i.e., untainted by the influence of urban modernity) and a potential point of connection between Black Americans and the African continent.Footnote 31 A belief in diasporic connections was also apparent in left-wing politics of the period. Black nationalist Marcus Garvey's call for “Africa for the Africans” symbolized a growing recognition that Black identity was not only connected through culture, but also anti-racist and anti-colonial politics.Footnote 32

Despite the modifier “New” in the New Negro, and frequent declarations of an emerging collective radical Black consciousness, Black empowerment during the 1920s did not break from conservative and liberal traditions in Black politics. Activism during the period often blended the radicalism of Black nationalism with advocating Victorian respectability and Booker T. Washington-style accommodationism. Alain Locke, regarded as the “philosophical midwife” of the Harlem Renaissance, largely couched his promotion of Black culture in the language of cultural pluralism and liberal democracy.Footnote 33 This was more than ideological differences among the latest generation of race leaders; rather, it spoke to contradictions within the movement. As historian Daniel Perlstein points out, “New Negro artists, activists, educators, and intellectuals . . . both embraced calls for Black self-direction and highlighted the centrality of interracial activity. They expressed a growing cultural self-confidence even as they accommodated white patrons. They announced a new racial pride even as they challenged racial essentialism.”Footnote 34 This last contradiction is particularly notable. While the very term “the New Negro” was evidence that race, as a category, was discursively constructed and could be publicly negotiated, those engaged in cultural representation gravitated toward what Hazel Carby has called “an aesthetically purified version of blackness.”Footnote 35 Even though many Black thinkers openly recognized the influence of America and Western thought on African Americans, they searched for the roots of a distinctive Black culture that could be surgically separated, broadly representative, and made to stand on its own.

It was in this context that literature deliberately designed for African American children appeared in the form of The Brownies’ Book. The periodical, which lasted for twenty-one issues during the years 1920 and 1921, evolved out of the NAACP's official magazine, The Crisis, which had published an annual “Children's Number” since 1913. During its two years of publication, poet, writer, and educator Jessie Fauset worked as the publication's main editor, receiving support from Crisis editor W. E. B. Du Bois. Under her leadership, The Brownies’ included a mix of stories, photos, puzzles, and poems. These features held in tension the playfulness and curiosity of childhood with the gravity of growing up Black. For example, the periodical was filled with images of school-aged African American children, offering a light and upbeat depiction their readers could relate to. At the same time, it was hard to ignore the way these pictures also served as a statement of Black self-worth, rebuking disregard for Black Americans in the children's book industry and upending the tacit conceptual linkage between childhood and Whiteness. Similarly, Du Bois straddled the imaginative and the political in a regular column entitled “As the Crow Flies,” which provided world news in the voice of an anthropomorphized crow. He positioned the crow as a caring elder, telling the young readers, “On and on I fly and fly to find the bits of news for my sweet babies—my dark Children of the Sun.”Footnote 36 The international landscape was presented as a place for childhood discovery—of kids learning about the big, wide world—but Du Bois also pointed to anti-colonial organizing and connections between all people of African descent.

A significant body of literature has demonstrated that The Brownies’ Book was not a side project of the Harlem Renaissance, but rather was part of the larger cultural dialogue that defined it.Footnote 37 A young Langston Hughes published one of his first stories in The Brownies’ Book, and other contributors included Renaissance luminaries Georgia Douglas Johnson and James Weldon Johnson. Its eclectic and creative style “birthed a kaleidoscope of butterflies in the exquisite variety of black youth literature emerging in its wake.”Footnote 38 The magazine demonstrated that a progressive approach to childhood—one grounded in play, fantasy, and community—offered a productive space for the construction of Black identity. During the 1930s, miles away from New York City, a group of African Americans would continue to take up this approach.

Contextualizing Black Children's Literature in the 1930s

The Great Depression shattered the exuberance that helped define the cultural politics of the New Negro movement. “Black artistic production had collapsed in the face of economic depression,” historian Jeffery C. Stewart writes.Footnote 39 With little disposable income, working-class Black Americans had to largely forgo the market for leisure activities, such as the arts and newspapers, shifting their energy to unemployment and the material conditions of poverty. Marcus Garvey, the most popular Black leader of the period, had been targeted by the federal government and eventually deported in 1927. Yet, as Garvey scholar Adam Ewing points out, the animating ideas of the New Negro movement, including an exploration of Black representation, were taken up as a part of grassroots movements across the Black diaspora long after the most visible Black leaders and artists faded from public view.Footnote 40

The Depression also initially devastated Black schooling in the South. Budgets for Black education were slashed to the bone by White southern legislatures, resulting in shortened school terms, swelling class sizes, and almost a total abandonment of school construction.Footnote 41 By the mid-1930s, the situation had begun to modestly improve. A mix of federal relief funds (though mostly directed toward White schools), pressure on southern states from Black community leaders, and a nascent NAACP legal campaign aimed at realizing Plessy's promise of “separate but equal” in schools helped spur growth in Black educational services, including the hiring of more teachers and increased per pupil spending in most southern states.Footnote 42

Along with these shifts, Black teachers began taking up the New Negro movement. To bring Black history and culture into their classrooms, African American teachers were often forced to look beyond traditional educational material such as textbooks, instead incorporating newspaper clips, poems, and pictures that affirmed their students’ budding racial awareness. Herman Dreer, an African American educator in St. Louis, observed this trend among teachers working in the city's segregated schools. Writing in The Journal of Negro History in 1934, he expressed admiration for the impressive pedagogical range his peers drew upon to bring the themes of the New Negro movement into their classrooms:

Some [African American teachers] use bulletin boards on which they put clippings giving accounts of the achievement of eminent Negroes. Others tell African myths and have their pupils learn Negro folk-rhymes and Negro proverbs. Some start their children in historical research by having them gather valuable material from elderly people and report the results of their investigations to their classes. Some teachers bring their Negro magazines to school and distribute them for use in the classroom. . . . Still others bring pictures of famous Negroes and dramatize events of Negro history.Footnote 43

Such efforts were not limited to St. Louis. In segregated classrooms throughout the South, African American students were introduced to units of study meant to display their race's achievement and counter mainstream messages of Black inferiority. These lessons were often delivered in the form of plays, pageants, song, and dance—mediums intended to encourage students’ emotional engagement with history and culture.Footnote 44

At the same time, children's literature for African Americans became an increasingly important avenue for portraying Black life. Many elementary teachers praised the educational materials produced by Carter G. Woodson's ASNLH but viewed his textbooks for high school students as having limited utility in their own classrooms. Harlem Renaissance literature and poetry posed its own dilemma: much of this work was written in a polemical style that was not well suited for young children. The Brownies’ Book was a clear exception, but there is little evidence to suggest that it was used in schools, especially after the publication ended in late 1921.Footnote 45 With few options, some Black elementary teachers took it upon themselves to produce children's stories for their students.

But constructing children's stories on the Black experience came with challenges. Writing in the Negro History Bulletin in 1939, an African American teacher from Cincinnati, Laura Knight Turner, posed the question this way: “What may we do for our youngest children . . . vivid of imagination, remembering only that which contributes to their present enjoyment, possessing vague concepts of number and time, loving sound for its own sake, therefore, enjoying repetition, rhythm, rhymes and alliteration? What of Negro History at this stage?”Footnote 46

A key part of the answer was Africa, which was viewed at once as a source of historical wonder and the potential origin of a Black identity. Teachers of young children were particularly drawn to the social life of African tribal societies. More so than the editors of The Brownies’ Book, African American teachers wanted to shield their elementary-aged students from the brutality experienced by Black people in America. Precolonial Africa offered an alternative. The continent's communal cultures presented a developmentally appropriate portrait of Black life.

In her article, Turner pointed to the value of African “fairy tales and myths,” which could engage young children's imagination. She contended that young children's “lack of knowledge of physical laws and of the world in general, make such material [fairy tales] at this age essential to the child's proper development.” Turner worried that Black students were only reading about princes and princesses whose “[faces are] white as the light of the full moon, eyes blue as the summer sky, and hair golden like the rays of the sun.” Black students needed to identify with the world of imagination that was presented in their books. “May we not write our own fairy tales and make black beautiful?” she rhetorically asked.Footnote 47 Several teachers would take up this call with Africa looming large in their work.

Black elementary teachers’ interest in Africa—and their desire to depict Black history in children's books more generally—was also motivated by a proliferation of new scientific studies on children's learning itself. The interwar period had seen a revolution in the study of children and their learning process. During the 1920s, psychologists not only began to focus more intently on children but also furthered research suggesting that children learned in developmental stages, meaning that general learning theories (built on studies of adults) did not apply to them.Footnote 48 By the late 1930s, there were at least seven prominent university institutes staffed by psychologists working to identify the criteria for children's learning stages. Despite adopting scientific methods for their research, psychologists, philanthropists, and policymakers approached this new field with an optimism that bordered on zealotry. Proponents argued that unlocking the precise development patterns of childhood not only allowed educators to identify “distorted and socially maladjusted children,” but also offered an “instrument for translating democratic aspirations and faith into practice.”Footnote 49 Calling this the “childhood development viewpoint,” advocates believed children were key to achieving widespread social reform. “Child welfare and the study of child growth and development may offer the most effective methods for dealing with our major social difficulties,” the philanthropist and educator Lawrence K. Frank emphatically declared in a 1939 speech. This new field of childhood psychology, Lawrence continued, “will be regarded as one of the more significant developments of the Twentieth Century.”Footnote 50 Black elementary teachers, like others involved in the education of young children, could not help but be excited about the transformative potential this research could have for their work.

Helen Adele Whiting

Helen Adele Whiting, an African American elementary educator in Atlanta, combined a New Negro-driven surge of interest in African cultures with the scientific interest in childhood development in two children's books, Negro Folk Tales for Pupils in the Primary Grades and Negro Art, Music and Rhyme for Young Folks, both published by the ASNLH-affiliated Associated Publishers. Whiting was not an average educator in the early twentieth century. After earning a bachelor's degree in pedagogy from Howard University in 1905, she worked for over four decades in various teaching, administrative, and supervisory roles.Footnote 51 Two years after graduating from college, she became an instructor of education at the Tuskegee Institute. By the early 1930s, she was the principal at Atlanta University's demonstration school; and in 1935 she became the state supervisor of “colored” elementary schools in Georgia. As an educator, she was deeply committed to progressive education, a philosophy in full flower while she studied at Teachers College at Columbia University at the beginning of the Depression. During her studies at Teachers College, she was taught by left-wing progressive educator William Kilpatrick and rural sociologist Mabel Carney, both of whom she continued to correspond with during her career.

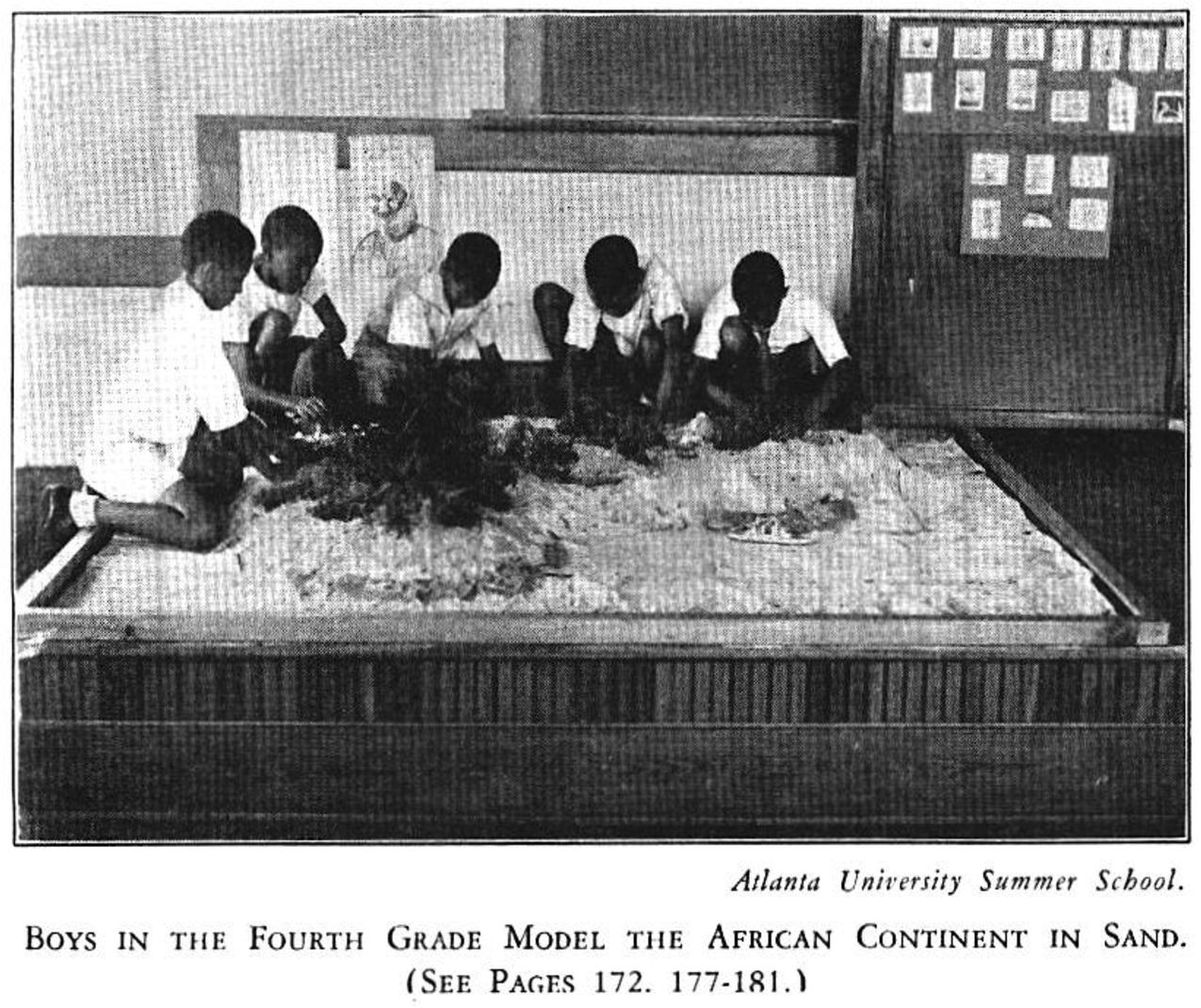

Her relationship with the progressive educational movement at Teachers College led her to contribute an article titled “Negro Children Study Race Culture” for a 1935 special issue on intercultural education published in Progressive Education.Footnote 52 Her article described two units she co-developed with students as a part of Atlanta University's 1934 summer school—a unit on African culture for fourth graders and another on African Americans’ cultural contributions for fifth graders. Much of the learning Whiting described was self-directed. It was the students who were drawn to the idea of mapmaking and decided to spend an afternoon modeling a map of Africa in a sandbox in the classroom (see Figure 1). Whiting provided readings on “the achievement of the African Negro and the American Negro in the arts,” but students had made the material their own, deciding to put on an “assembly for the rest of the school in order to dramatize what they had learned.”Footnote 53 As students embraced Black history in their own creative work, Whiting believed that their racial awareness was beginning to blossom.

Figure 1. A Picture of Students from Helen Adele Whiting, “Negro Children Study Race Culture,” Progressive Education 12, no. 3 (March 1935), 175.

Whiting published Negro Folk Tales and Negro Art, Music and Rhyme in 1938. Though published separately, she imagined these works as two parts of a single unit of study. The first, Negro Folk Tales, was a twenty-two-page booklet. It started with seven African myths, which included a creation story (“How the World Began”), explanatory myths of animals and their domestication (“Hog and Wild Boar” / “Dog and Jackal”), and three “American Negro tale[s]” developed during slavery. Whiting presented the stories without comment, though the cultural connection between Africa and African Americans was self-evident. The first six African tales blended seamlessly into the next three African American tales, the only indication of the separation being the note “American Negro Tale” below each title. The myths from Africa and America also followed consistent patterns, such as those centered on teaching lessons by anthropomorphizing animals and offering stories on the origins of social and natural phenomena. And, as Whiting's preface stated, the book overall was intended to introduce readers to a collective “Negro race culture.”Footnote 54

Whiting's approach in Negro Folk Tales reflected her commitment to progressive pedagogy. By the late 1930s, she had helped popularize what she called “life-related” lessons, stressing that the substance of education needed to be grounded in students’ local (and personal) contexts. For example, writing on rural education in 1937, where the vast majority of Black schooling still took place, she explained that “[educational] subject matter is only important as it is tied up with the problems of living to these areas.”Footnote 55 This observation on the interconnection between life and learning was not new to progressive theorists, but many White educators had ignored one of the most pressing life problems for African American education: the centuries-old idea of Blackness as a marker of stigma. Whiting's Negro Folk Tales had taken this as its starting point, teaching reading and engaging children's imagination through an affirming picture of African and African American folk tales. At the same time, she wrote Negro Folk Tales with the developmental needs of young children in mind. As she noted in the beginning of the book, her writing was designed with a “repetitive story pattern” meant to “enable children . . . of the first three grades to read [it] without difficulty.”Footnote 56

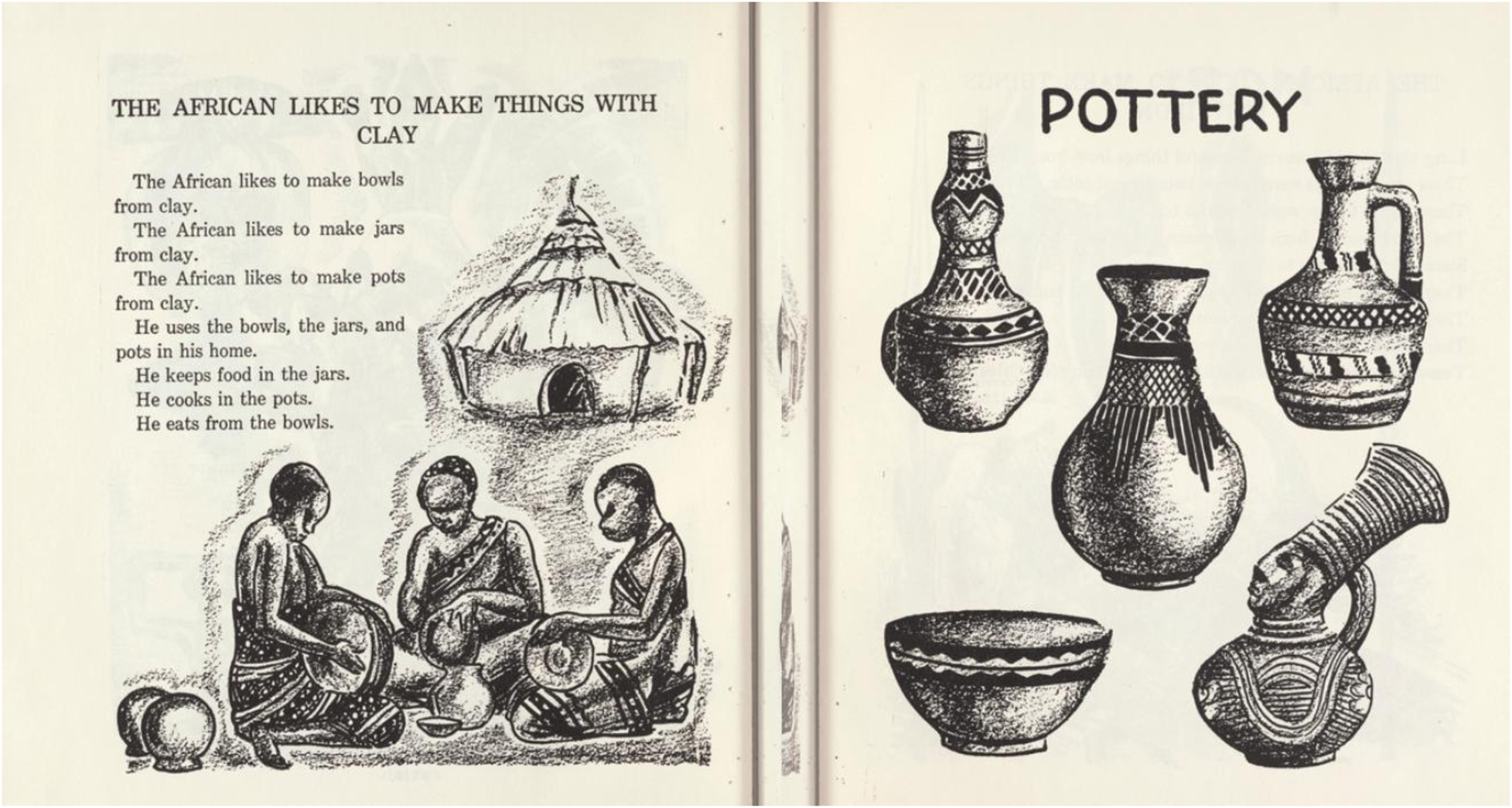

Similar considerations were central to her second booklet, Negro Art, Music and Rhyme, which also featured short stories about African and African American culture.Footnote 57 However, rather than simply presenting material, Whiting adopted a more descriptive tone in Negro Art, Music and Rhyme, a style that enabled her own perspective to come through. In her descriptions, she represented African cultures as worthy of recognition—and part of complex societies—but also as relatively monolithic. Each page introduced a new artistic and cultural activity that characterized “the African.” A section on art began, “The African likes Art. He likes to make pretty things.”Footnote 58 This becomes part of the rhythm of the book itself. “The African likes to carve wood”;Footnote 59 “the African likes to make things with leather”;Footnote 60 “the African likes to weave palm cloth.”Footnote 61 For Whiting, African life was, in almost every respect, cultural and collective—a fact that she offered to African American students as a source of pride. Writing on African art, for example, she noted that “artists and people all over the world like African art. Many artists try to do their art like African art.”Footnote 62 From Whiting's perspective, Europe and America were beginning to recognize the cultural contributions of Africa, and Black students had every right to be proud.

Throughout the book's depiction of Africa, art is perhaps the most prominent theme. In a section called “The African Likes to Make Things out of Clay,” Whiting highlights not only the usefulness of their pottery, but the artful design of their work. This is also evident in her presentation of iron tools as well as the weaving and embroidering of palm cloth. But the illustrations included in the book enabled young readers to connect with the aesthetic landscape of African life, more so than the words on the page. Like most of the Associated Publishers’ children's books, Negro Art, Music and Rhyme was illustrated by Loïs Mailou Jones, an emerging Black artist living in Paris in the 1930s. As scholars have noted, Jones's paintings and illustrations during this period were not only an outgrowth of the Harlem Renaissance, but also influenced by Pan-African themes of the early Negritude movement.Footnote 63 Her examples of African pottery (see Figure 2) portrayed a natural blending of art and life and a harmony between social utility and creative expression. This outlook aligned with Whiting's educational philosophy, in which art and learning were deeply intertwined. It also reinforced a central message of the book—that Africa, and artistic expression, held the basis of a shared Black identity.

Figure 2. Pages from Helen Adele Whiting, Negro Art, Music and Rhyme for Young Folks, illustrated by Loïs Mailou Jones (Washington, DC: Associated Publishers, 1938), n.p. Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections.

In the second part of the book, “American Negro Song, Dance, and Rhyme,” Whiting emphasized Black cultural linkage, particularly in music. “Negro songs are beautiful,” she declared, and “the songs come from African music.”Footnote 64 African American spirituality, she also noted, had its roots on the continent. Such observations, far from being original, reflected an ongoing conversation on Black identity and its relationship to Africa. Countee Cullen's famous poem “Heritage” had mused over the question “What is Africa to me?” without offering a straightforward answer. Scholars like Alain Locke provided a clearer answer: Black Americans had a distinct culture that, to a significant degree, derived from African customs and cultural patterns.Footnote 65 For Whiting it was important that this message went beyond academia and adult audiences consuming Harlem Renaissance art and literature. Black elementary school students needed to explore their cultural link to the motherland.

Though written in the prose of children's literature, Whiting's books were engaged in the racial politics of the New Negro movement, particularly in the way she sought to construct a unified (and diasporic) Black identity. In her telling, Africa was a symbol of Blackness shared by those across the diaspora, and it served as a rebuke to portrayals of Black people as culturally inferior. Whiting was not particularly concerned about taking up Africa on its own terms, but rather sought to show how the continent could be used to shape Black identity and affirm the racial awareness of students in Jim Crow schools. Her books did not try to be original works of research; she was open about building off the work of Black artists and cultural anthropologists, such as Franz Boas, who had imagined precolonial Africa as a symbol of Black culture. Yet neither was she simply reproducing others’ research. Where she differed was in her commitment to aligning her portrayal of Black culture with the learning needs of young children. To a significant extent, Africa's past served as a pedagogical tool for Black teachers like Whiting—a means of stimulating children's imagination. Such portrayals of Africa did not escape the historical context in which they arose. But even while reinforcing some Western tropes of Africa, Whiting, like many African Americans during the 1920s and 1930s, believed the affirming portrayals of Blackness they produced would have a positive impact on their students.

Whiting's books were regularly advertised in national Black publications and included in bibliographies of Black children's literature throughout the 1940s. For example, well into the 1940s, every issue of The Crisis listed both Negro Folk Tales and Negro Art, Music and Rhyme in its “Books About Negroes” section. At the time of the publication of Whiting's two books in 1938, articles praising them appeared in the Atlanta Daily World, New York Age, and Negro History Bulletin, among others.Footnote 66

Of course, Whiting was not the only Black educator publishing children's literature. At roughly the same time as Whiting, Jane Dabney Shackelford published The Child's Story of the Negro, which quickly became the most popular book in the genre.Footnote 67

Jane Dabney Shackelford

Jane Dabney Shackelford was born in 1895 in Clarksville, Tennessee, a small town on the Kentucky border. At a young age her parents moved the family north to Logansport, Indiana. In handwritten stories prepared while Shackelford was drafting an autobiography that was never published, she described early twentieth-century Logansport as a happy and integrated town and claimed that her White teachers embraced her educational ambitions.Footnote 68 During World War I, she enrolled at Indiana State Normal School (now Indiana State University), graduating in 1919. Right out of school she began her teaching career at segregated elementary schools in Terre Haute. Her first job was as the sole teacher at a one-room school with thirty-five pupils and five grades.Footnote 69 After her school building burned down under suspicious circumstances in 1925, she was transferred to Terre Haute's Booker T. Washington School—a much larger, age-graded school for African American children. She remained there until her retirement in 1962.

Shackelford was a model of the Black middle class. She was a prominent member of her local chapter of the Black sorority Alpha Kappa Alpha, the captain of her school's Girl Scout troop, and a local church leader. Like many African American educators, her status as a respected community leader in Terre Haute formed an important part of her identity. As historian Adam Fairclough suggests, Black teachers’ social position during Jim Crow came with its own contradictions: they acted as advocates for their students, schools, and communities but also reinforced narratives of self-help and, at times, looked down on Black working-class culture.Footnote 70 In Shackelford's case, the pressure to live up to her social status as a member of the Black middle class shaped not only her values but also her public image. In one example, as she gained acclaim for The Child's Story of the Negro, press outlets regularly characterized her as a widow raising her young son, Montrose.Footnote 71 Public records, however, contradict this story. She is listed as “divorced” in the 1930 census, while marriage records show that her former husband, Kyzer, remarried in Coles, Illinois, in June 1923.Footnote 72 Perhaps spurred by her divorce, she refocused on her career by enrolling in a master's program at Teachers College at Columbia University in the mid-1920s. The master's at Teachers College was a summer program, allowing her to keep teaching back in Indiana. She earned her degree in 1927.

It was during one of her summers in New York that Shackelford began to contemplate the book that would become The Child's Story of the Negro. As she recounts in one autobiographical note titled “How I Became a Writer,” she was encouraged to publish her writing by one of her professors, who took note of her work in a high school composition class of two hundred teachers in 1926.Footnote 73 Later in the summer, she decided to visit the new Arthur Schomburg collection of African American and African materials housed in the Harlem public library on 135th Street. She traveled the roughly twenty blocks uptown from Columbia to visit this newly acquired collection. While it is unclear whether this was her only trip to Harlem—or whether she took the time to absorb the political and artistic life of this Black mecca (or to experience its famous nightlife)—her trip to the library proved formative. There she found thousands of books by and about people of African descent, representing not just the United States but all over the world. For Shackelford, it might have felt as if the entirety of the Black experience was contained in the many volumes she browsed. During her visit, she began to think of her students. “I asked the librarian if there were any histories of the Negro for primary children,” Shackelford recalled. The librarian's reply was simply, “There is no such book,” and encouraged Shackelford to write one herself.Footnote 74 This origin story provides a direct link between the New Negro movement as it existed in Harlem in the 1920s and the book Shackelford published over eleven years later.

As a Black children's book written by a teacher in the 1930s, there was only one publisher that would realistically release it: Carter G. Woodson's Associated Publishers. Shackelford first reached out to Woodson in 1934, and the two engaged in an extensive correspondence over the next four years. One thing that becomes clear from their correspondence is that Shackelford was nothing if not persistent. When she first contacted Woodson about her book, she was quickly dismissed by his secretary, who told her that people don't buy books during a depression.Footnote 75 Despite this lack of encouragement, Shackelford continued to write Woodson about her idea and submitted a manuscript in 1935. After waiting more than six months for a reply, Woodson told her that the manuscript was not complete and would not be considered. To commit to the book at this stage, he explained, “would be like buying a pig in a bag without looking to see whether it is fat or lean, large or small.”Footnote 76 When she sent an updated version, Woodson's response was more encouraging, calling her manuscript “worthwhile” but warning her “not [to] become angry” at the criticism that followed.Footnote 77 (He recommended substantial revisions.) After another round of edits in 1936, Shackelford was finally offered a contract: she would get 5 percent of each copy sold, the going rate for a first-time author, she was told. Still, it took another year for Loïs Mailou Jones to finish the book's illustrations and six months after that to copyedit the manuscript and correct the final proofs. Woodson had hoped to have The Child's Story out by the summer of 1937 to “get it in the hands of scores of teachers as they attend[ed] summer school,” but the book did not appear until January of 1938.Footnote 78

Shackelford's Child's Story had much in common with Whiting's books. It was written as a collection of stories in prose that, when read aloud, sounded as if the teacher were speaking directly to her students. “You remember that in parts of Africa there are only two seasons,” a line in the beginning of the book reads.Footnote 79 In addition, the book had a heavy emphasis on Africa, with over half of the stories focused on its geography, nature, and pre-industrial culture. However, what set Shackelford's book apart was the author's attempt to write a grand historical narrative of African American life, from Africa to the present, for children. The book's comprehensive scope may have been a selling point for Black schools with limited funds to buy educational materials. It also made The Child's Story much longer than the average children's book—over two hundred pages. Still, its short two- to four-page chapters, its focus on story, and Jones's illustrations made it digestible for young readers.

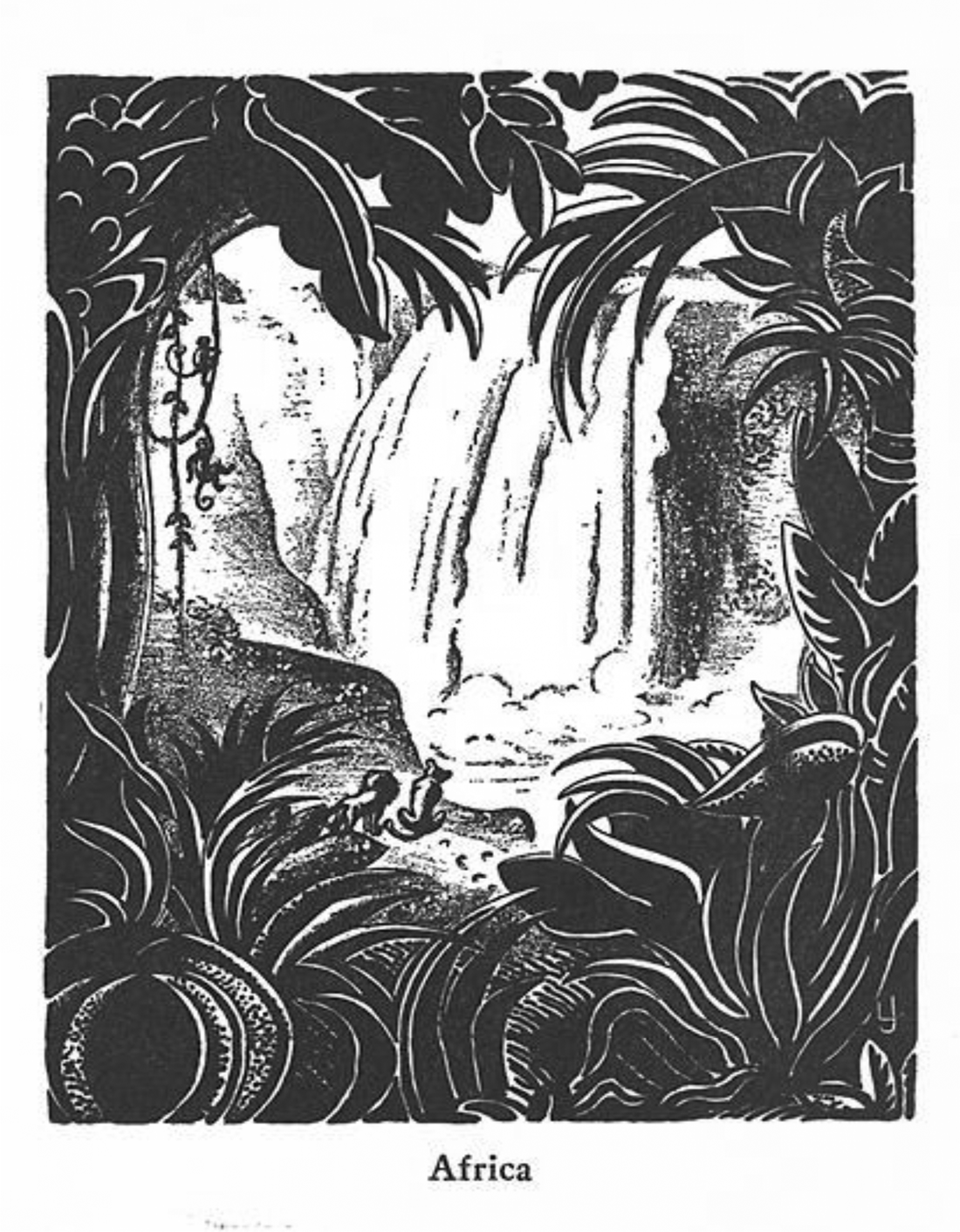

Like her contemporaries, Shackelford presented Africa in complex and contradictory ways. Similar to Whiting, she did not explore classical African civilization—which some African Americans invoked as an embodiment of Black achievement—and instead focused on depicting tribal societies. Shackelford portrayed Africa not only as part of Black children's lineage but in terms she believed fit their learning styles. In The Child's Story, the continent was a land of community, music, and fairytales. It was a place of natural beauty and talking animals, of possibility and wonder (see Figure 3). Shackelford portrayed these as positive aspects of Black culture, but the continent also came off as mysterious and more disconnected from African American life than in Whiting's portrayal. “Far, far across the ocean, miles and miles from our country,” Shackelford wrote in the opening line of the book, “is a wonderful continent called Africa.”Footnote 80 She included stories and myths that invited her young readers to imagine life in Africa as a kind of fantasy, while also praising its rich history and art. Shackelford's depiction of Africa promoted a diasporic Black identity, though she was more hesitant than Whiting to fully embrace African Americans’ cultural linkage to the continent. And while The Child's Story was not Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness—a demeaning picture of Africa as dangerous and wild—it did show that teachers’ attempts to positively portray Africa to their Black students did not mean a transcendence of stereotypes that shaped the West's imagination.

Figure 3. Picture of Africa from Jane Dabney Shackelford, The Child's Story of the Negro, illustrated by Loïs Mailou Jones (Washington DC: Associated Publishers, 1938), xi. Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Shackelford's contradictions remained as she moved from a discussion of Africa's climate and wildlife to a focus on its people and their culture. Despite maintaining a drumbeat of praise, she also highlighted dissimilarities between Africans and African Americans. “An African village is a very queer sight,” Shackelford proclaimed in the first line of the chapter, “The Homes of the Africans.”Footnote 81 She described African homes as huts made of mud, sticks, and palm leaves. In follow-up questions at the end of the chapter, she asked: “How is the home of the African different from yours? Why is it different?”Footnote 82 She also conveyed this difference with her choice of adjectives. Africans were “queer,” “strange,” and even “primitive.” Yet these words were tucked into chapters presenting African people as early inventors, skillful artists, and powerful storytellers. And while the text asked African American students to consider the ways in which they were different—and more modern—than the monolithic people and culture she described, she also revealed ways that Africans were superior to Whites and a justifiable source of pride. In a chapter on African sculpture, for example, she remarked that when academics in Paris studied a woodcarving from the continent, they had to admit the sculptor that carved the piece was a “much better workman than many artists in America or Europe.”Footnote 83 Another chapter on African music asked, “Did you know that the Africans were the first people to use stringed instruments?”Footnote 84 Even the medicine man, who is treated as a “very strange” character, was noted for being able to “cure some diseases that the white doctors could not cure.”Footnote 85

Shackelford's approach spoke to a transition in the way African Americans were portraying Africa during the period. Late nineteenth-century Black activists, fixated on establishing Black people's place in the ideal of civilization, had embraced their connection to Africa, but also portrayed its people as less modern and industrialized than their Black peers in the New World.Footnote 86 By contrast, artists and writers during the Harlem Renaissance were far less enamored with this civilizationist picture of the world's racial groups. Indeed, in their efforts to connect African and African American cultural life, some Black intellectuals in the 1930s sought to distance their culture from the maladies of modern industrial capitalism, which they believed had intensified wars, inequality, social unrest, and colonial exploitation. Shackelford was not an open critic of modernity, and her book, at times, adopted the same paternalistic depictions of Africa that had been dominant among a prior generation of Black activists. But she also adopted a picture of Africans as existing within a communal society with rich cultural patterns—a conception that had taken hold during the 1920s. For Shackelford, these two visions of Africa stood side by side.

Shackelford was weighing other considerations as she sought to portray Black identity in her book. In particular, she was negotiating the politics of Jim Crow. Even with an upsurge in radical politics among African Americans during the Depression, many Black middle-class educators remained wary of political commitments that could be viewed as overly confrontational toward southern racial apartheid.Footnote 87 In 1895, Booker T. Washington proposed a political “compromise”—Whites would consent to African American institutions and economic mobility and, in return, Black Southerners would not push for civil and political rights. Teachers like Shackelford created a new compromise, one that responded to the era of the New Negro and an emphasis on Black curricular inclusion. During the 1930s, southern education officials had expressed a moderate openness to positive representations of African Americans in elementary curricula, but their limited acceptance of Black-oriented children's books would quickly diminish if they viewed Black teaching as a direct challenge to White supremacy.Footnote 88 Shackelford believed it was possible to instill race pride without directly challenging the status quo. She hoped to develop young students’ mental resilience to Jim Crow degradation and promote a culture of Black self-respect that would ultimately support the wellbeing of segregated communities. For many Black teachers, children's literature was an early intervention in a larger project of community uplift—one that attempted to carefully navigate portrayals of Blackness by balancing race pride and political moderation.

But was this balance really feasible? Perhaps not. In The Child's Story's account of enslavement, for instance, Shackelford deliberately avoided any discussion of racial violence or physical and psychological trauma. She explained in one of her autobiographical notes that she had gone into writing a chapter called “Life on a Southern Plantation” with the intention that Black children “would not hate white people because of the institution of slavery.” She soon discovered the problem with this strategy, explaining:

[In my first draft] I emphasized not cruel masters, but the happy times some slaves enjoyed in the evening. Dances—parties—visiting other plantations—going to camp meetings etc. When I finished reading this chapter [aloud to my class], one little girl raised her hand snapping her fingers excitedly and when I called on her she exclaimed, “O’ Mrs. Shackelford, could we be slaves again?” I spent the following weekend rewriting “Life on a Southern Plantation.”Footnote 89

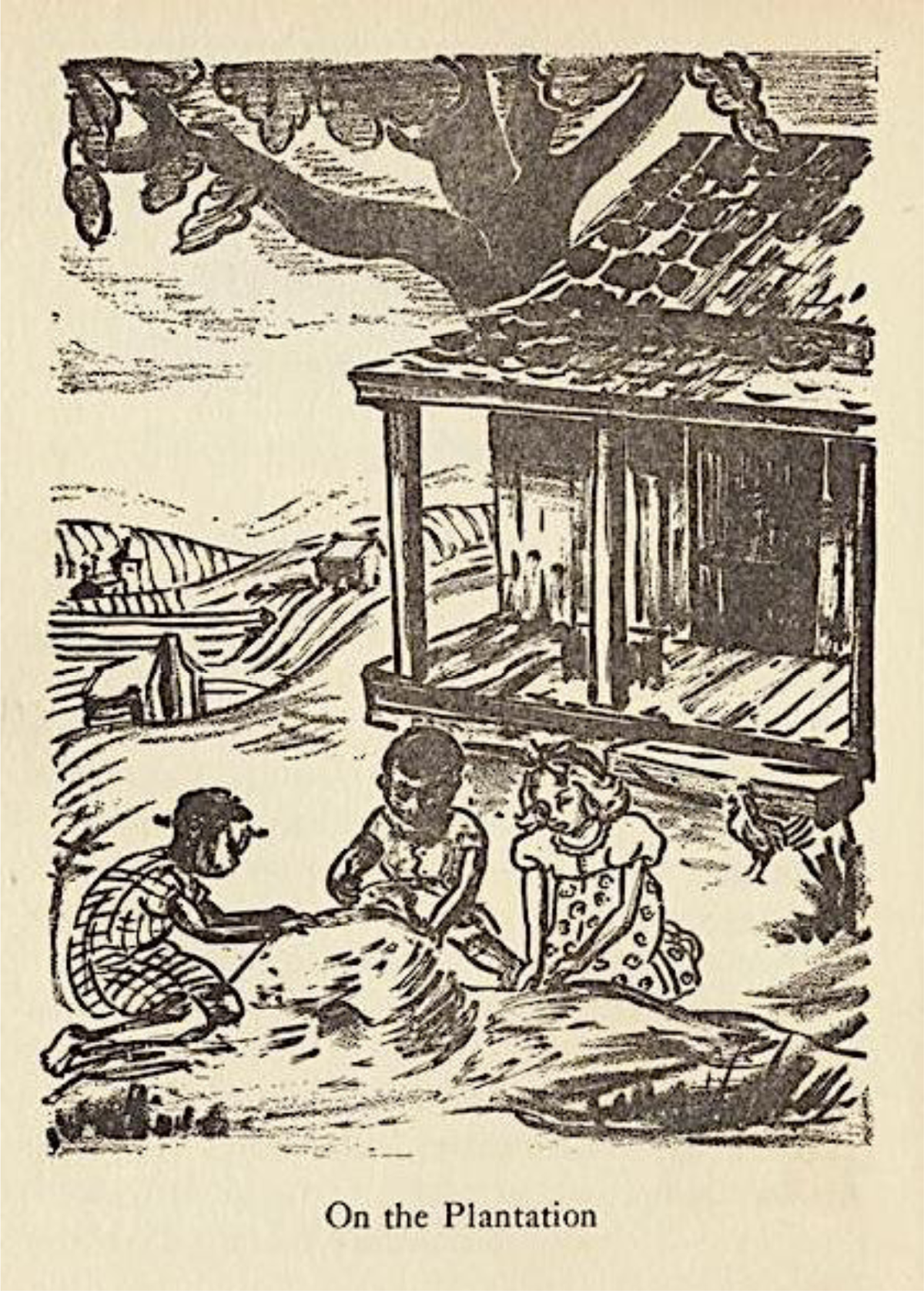

Even with Shackelford's rewrites, the published version of this story went out of its way to avoid any mention of the cruelty of slavery. It emphasized “kind masters”: “If the master were [sic] very wealthy and kind to his servants, he gave each family a dry airy cabin, a poultry house, and a vegetable garden.”Footnote 90 The book's illustration of plantation life was of two Black children playing with a White girl against the backdrop of an idyllic country landscape dotted with large “airy” cabins (see Figure 4). To be sure, Shackelford's portrayal of slavery upended some stereotypical representations of enslaved people—the idea of Black people as the “pickaninny, the fool . . . [and] the cheat.”Footnote 91 In The Child's Story, enslaved people were spiritual, musical, and community-oriented. They were incredibly hard workers. “All day long slaves were working—working—working,” Shackelford explained.Footnote 92 But her depiction of enslaved labor was framed less as a cruel institution than as a source of Black pride: the work of enslaved people had been essential to the infrastructure of the American republic. Black children reading The Child's Story may not have wanted to return to plantation life, but they walked away with only a vague sense that oppression, brutality, and trauma had defined the institution. Perhaps even more than The Brownies’ Book, Shackelford sought to introduce Black identity to young children by positioning oppression as a nebulous background to the message of race pride and unity.

Figure 4. Illustration from “A Southern Plantation,” a chapter in Shackelford, The Child's Story of the Negro, 102. Source: New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The final chapters of Shackelford's book consist of short biographies of prominent African American men (as well as Phillis Wheatley). She dedicated chapters to the lives of Charles Henry Turner, a pioneering figure in zoology; Booker T. Washington, the famous educator and founder of Tuskegee; and Jan Matzeliger, an inventor who created a machine to help automate the production of shoes. Though they may not have known it, readers of The Child's Story were being introduced to a long tradition of writing biographies of prominent Black figures as “vindication” against charges of racial inferiority.Footnote 93 For Shackelford, these men were representatives of Black people collectively, a testament to the potential of the race. Shackelford's child-friendly biographical accounts of Turner, Washington, and Matzeliger shared similar narrative arcs. All these men had gone up against the odds of racial oppression, but with hard work had managed to succeed in their endeavors, becoming a credit to their race.

The Child's Story's final chapters were steeped in heroism of the kind that remains a common trope of storytelling for young children. Yet, in the context of the New Negro project of Black self-racialization, this approach was double-edged. While Shackelford acknowledged the impact of racism in the lives of Black Americans, she also suggested that it had little bearing on her students’ future success. For example, Washington was treated as a model of Black citizenship—a hero who overcame his beginnings as an enslaved person to establish the Tuskegee Institute. In truth, the South's racial caste system was not something to be simply overcome. Black Southerners faced a constant threat of violence and cultural norms that deliberately undermined their social dignity. These experiences were tied into larger systems that relegated African Americans to low-wage employment and excluded their participation in politics. As Shackelford well knew, the systems her students faced were, at best, something to be carefully navigated rather than overcome.

Still, inspiration remained a key component of Black Americans’ struggle for freedom, and Shackelford likely viewed this as particularly important for children. Her students needed to be exposed to Black success, which was omitted from standard curriculum material. The pages of The Child's Story helped to affirm Black potentiality and construct a “New Negro” that students could connect to.

Conclusion

Whiting and Shackelford continued to write for African American teachers and children beyond 1938, when all three books discussed in this article first appeared in print. Yet, their approach to children's literature began to shift toward what scholars have identified as midcentury American “racial liberalism”—the growing influence of the values of pluralism, tolerance, and color blindness in mainstream racial discourse.Footnote 94 To some extent, these values had already been apparent in Whiting's embrace of progressive education, a commitment that only strengthened during the 1940s. During the next decade, her work emphasized the transformative potential of arts-based education in a “bulletin” she wrote “[for] pupils in Georgia,” called Clay Is Fun (1945), while also advocating for democratic (or community-based) approaches to curriculum-building in the pages of the Journal of Negro Education.Footnote 95 In 1945, Shackelford published her second, and final, book for children, a picture book titled My Happy Days. This book was a break from The Child's Story, which had centered Black identity as distinctive and an outgrowth of culture and history worthy of being embraced by young children. My Happy Days followed Rex, a young African American boy whose modern middle-class life, Shackelford contended in her unpublished autobiography, represented the “average” Black family.Footnote 96 Rather than focus on cultural markers or shared history, Shackelford sought to position middle-class aspirations as integral to Black families and their racial identity.

These shifts only reinforce that Whiting and Shackelford were both producers and products of the racial context of their time. Since the First World War, that context had been a broad and diffuse project to redefine Black identity, which took hold in African American communities. The New Negro movement, as contemporaries labeled their efforts, became infused into Black public culture. Historians often remember this as the Harlem Renaissance and associate it with the Black arts movement and Black nationalist politics. But a full accounting of the movement and the public conversation on racial identity must include African American teachers and the curriculum materials they developed. During the 1930s, segregated schools in the South had become another site for constructing a radically affirming Black identity.

Children's literature written for African American students played an important role in this effort. For Helen Adele Whiting and Jane Dabney Shackelford, children's books offered the possibility for imagining a new “regime of representation” and infusing this in the education of young students. To be sure, their books were a product of their time and place and not without compromises with the racial status quo. But they also took up a pivotal and emerging question: How should Black life be portrayed in ways that align with the developmental needs of African American children? No single answer emerged, but their work sent a message of Black self-worth that went beyond the specifics of their content. Whiting's and Shackelford's books sent the message to Black readers that they were not as the White world portrayed them, devoid of culture and social achievements. They sent the message to Black students that they were worthy of love, respect, and praise. And they sent the message to the tens of thousands of Black elementary teachers who overwhelmingly dominated the ranks of the teaching force that the standard Eurocentric curriculum was not a forgone conclusion. While Whiting and Shackelford were among a rather small group of African American teachers to publish children's books before World War II, their books were widely used and, perhaps more importantly, served as a highly visible symbol of the intellectual underpinnings of Black teaching.

Amato Nocera is an assistant professor at North Carolina State University and working on his first book, titled Constructing a Black Curriculum: Race, Representation, and the Politics of Knowledge, 1890-1945. He thanks Laura Chávez-Moreno, Derek Taira, his fall 2021 doctoral class, and the anonymous reviewers and HEQ editors for their valuable feedback on this article. He also acknowledges the generous financial support provided by the Spencer Foundation Racial Equity Research grant.