1. Introduction

Studies on the Middle Persian (MP) interpretation of the Avestan (Av.) texts, traditionally called Zand, have recently received significant scholarly attention (e.g. Zeini Reference Zeini2020; Malandra and Ichaporia Reference Malandra and Ichaporia2013; Cantera Reference Cantera2004). These studies undertake to clarify the reception of Avestan language and texts in later periods and the extent to which the translations of the Avesta influence MP texts. Another crucial question that has been posed in recent years is whether these translations could still contribute to our understanding of the Avestan texts. It seems that the old tradition of translating and interpreting the sacred texts reflected in Zand would at least partly contribute to our analysis of the Avesta. This article presents a study of the disputed Av. term ī̆šti- and its MP translation to establish how precisely MP translators understood the Av. term in their interpretations.Footnote 1

Moreover, it aims to clarify the meaning of īšt as a vocabulary item in MP. Before examining Av. ī̆šti-, it is essential to discuss some of the features of MP translation texts and the process of their translation, to clarify the context of our discussion. Following this, the etymology of Av. ī̆šti-, its syntactic context, and its derivatives are discussed. Finally, MP īšt and its appearances in Zand and other MP texts are analysed and compared diachronically.

In this article, the examples consist of the Av. original sentence, MP interlinear translation, and MP comments, respectively. OAv. translations are adopted from Humbach (Reference Humbach1991a).Footnote 2 The translations of īšti- are deleted to visualize the notion in the lines. Other translations are also consulted to check whether the Av. text's alternative interpretation matches the MP translation. Examples from other texts are either cited from a reference or translated by the author.

1.1. Zand

Before engaging with the word and its usages, it is beneficial to review the qualities of Zand. It will clarify our discussion about the occurrences of the word in the Middle Persian translation of the Avesta.

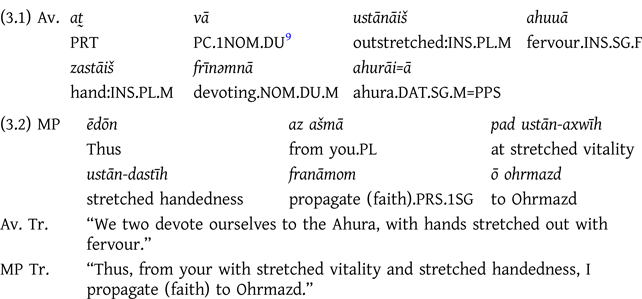

Zand includes a loose word-for-word translation of the Av. Text, usually accompanied by an idiomatic translation into MP and a commentary. For example, the Old Avestan (OAv.) phrase ustānāiš … zastāiš (Y.29: 5) “with outstretched hands” is glossed into MP pad … ustān dast “with *stretched hands” and explained by a comment tuxšāgīhā “diligently”. The MP gloss has no obvious sense in MP.Footnote 3 Therefore, an adverb modifies it. The word-for-word translation usually follows the source word order (Josephson Reference Josephson1997: 153–5; Cantera Reference Cantera2004: 241) and a (pseudo-)etymological approach according to the phonetic similarity (Andrés-Toledo Reference Andrés-Toledo, Gaspa, Michel and Nosch2017: 398; Musavi Reference Musavi2019: 293), in this example, the gloss ustān for the Av. ustānāiš is thus.Footnote 4 Therefore, it is usually possible to distinguish the translation of Avestan words from comments, although the comments are not specially marked as such in the manuscripts.Footnote 5

Malandra and Ichaporia (Reference Malandra and Ichaporia2013: 1) have observed a twist in the terminology: they suggest that the word-for-word translation of the Av. texts should be referred to as “gloss”. Their suggestion is supported by the fact that it would attempt to transfer every source word's notion interlineally, indicating very little about MP grammar. By contrast, MP comments would represent every phrase's proper MP translation wherever they are appended to the text.

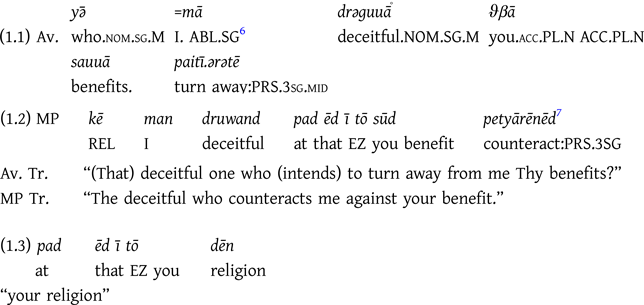

The MP interpretation follows the source language word order to the extent that it frequently violates the standard MP syntax. For instance, in example 1.2 (Y.44: 2d) below, the MP translation kē man druwand pad ēd ī tō sūd petyārēnēd is scrambled and follows the Avestan word order, while the canonical MP word order would be (ōy) druwand kē man pad ēd ī tō sūd petyārēnēd. Therefore, a comment is added to clarify the intended meaning of the word-for-word translation. Here, the interpretation (1.3) of pad ēd ī tō dēn “(at) your religion” is also provided between the lines and explains pad ēd ī tō sūd “(at) your benefit” (end of 1.2).

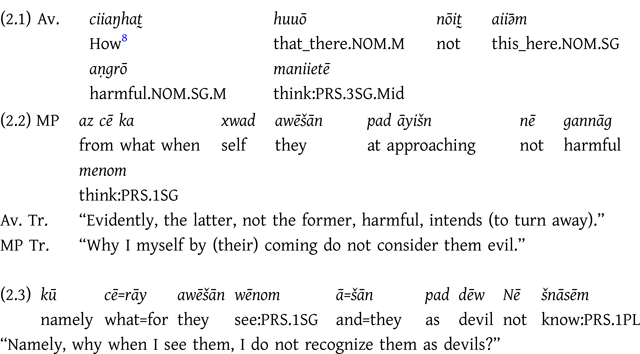

However, in example 2.2 (Y.44: 12e), the Avestan word order is not strictly followed, since Av. nōit̰ and MP nē occur in different positions in the sentence. The insertion of the pronoun xwad in the MP translation, with no Av. counterpart, also contributes to communication of the meaning. Still, since the MP translation follows the (pseudo-)phonological etymology, the intended meaning is not clear. The problem is that MP menom is used to translate Av. mainiietē, since they both derive from OIr. MAN “think, consider” (Cheung Reference Cheung2006: 262). Still, MP menīdan does not demonstrate the meaning that the Zandist understands, i.e. šnāxtan “know, recognize”, therefore a comment (2.3) was necessary to clarify, using šnāsēm:

Moreover, some words used in Zand are not (or are no longer) used in Middle Persian (Cantera Reference Cantera2004: 246). Thus, comments are introduced to convey the message either by paraphrasing, adding more information, or rendering different possible interpretations. For example, the MP adverbial phrase andar druzōdmān, which glosses OAv. drūjō dəmānē (Y.49: 11d) “in the house of deceit” is explained by the MP comment andar dušox “in hell”. The could be because druzōdmān is not a real or frequent MP word and would need clarification. Another possibility is that the “house of the deceit” is understood, but is not clear and precise. Therefore, an interpretation clarifies that it is synonymous with “hell”.

On the one hand, studying these comments contributes to our understanding of Zoroastrians in that era and their conception of the Avesta. It also demonstrates their translation techniques and linguistic skills (Cantera Reference Cantera2004: 268). The latter point is of particular linguistic interest since Avestan is a more synthetic language in which noun declension and verb inflection are intricate. MP employs a simpler verbal inflection. The active/middle distinction is lost, and fewer non-finite verbs are included in the verbal system. The loss of the wide range of non-finite forms in MP limits the syntactic possibilities of the translated forms, changes the syntax of MP compared to Old Iranian, and makes it difficult to render a MP word-for-word translation of the Av. text. For example, the NP ustānāiš zastāiš in (3.1) is translated by the prepositional phrase pad ustān dastīh. As in this example, MP usually exerts adposition to express the case except for nominative, accusative, and vocative cases. Spiegel's early observations show that noun phrases in the nominative, accusative, and vocative cases are not usually periphrastic. Still, other cases use prepositions, including az, pad, ō, rāy, andar, and the like (Reference Spiegel1860: 21–23; Cantera Reference Cantera2004: 269).

Another strategy is to translate the non-finite form into a conjugated verb, as in example 3 (Y.29: 5a):

The Av. middle-voiced present participle frīnəmnā “devoting” is translated to the finite verb franāmom “I promote”. Likewise, in this article (example 11, below), we will see how the Av. ī̆šti- is also sometimes understood as a verb.

Middle Persian translations benefit from several Avestan loanwords, artificial neologisms, and genuine MP vocabulary.Footnote 10 An artificial MP neologism is probably seen in the MP compound ustān-axwīh. Since the composition is structurally uncommon, one would assume that this is not a normal formation. An example of an Avestan loanword in MP is apagaiiehe “of death”,Footnote 11 which is only observed in a few of the Av. manuscripts,Footnote 12 but frequently in the MP glosses and comments on the translation of Av. texts to mean “dead”.

The attestation of several elements of MP translated vocabulary, particularly in cases such as apagaiiehe, makes it essential to think of a multi-step process in interpreting these texts. The Av. texts were read, analysed, and memorized traditionally in a place called hērbedestān (Kotwal Reference Kotwal2012). This was a form of advanced priestly school where Zoroastrian priest-teachers (hērbedān), read, elaborated on, and interpreted the Avesta orally for students (hāwištān), who memorized and retained the exegesis so it could be taught to the next generation. After the introduction of writing, hērbed also undertook to write down their interpretations. The names of two hērbed authors are mentioned in the colophons of ŠNŠFootnote 13 and PT.Footnote 14

Nevertheless, the case of MP īšt has similarities and differences with neologism and loan translation. While it is often used in the translation of the Av. ī̆šti-, it is different from apagayiiehe as it has gone through a phonetic evolution where it lost its final vowel, as well as a semantic change that is discussed further below.Footnote 15

2. The etymology of Avestan ī̆šti-

Avestan ī̆šti- is a feminine noun that is understood and translated in different ways by Avestan scholars. It has been taken to include a wide range of related meanings, from “assets”,Footnote 16 to “ability”,Footnote 17 “power”,Footnote 18 “command”,Footnote 19 “wish”, and “ritual”.Footnote 20

Humbach concluded that the word corresponds to more than one Indo-Iranian word and translated it differently in different contexts (Reference Humbach1991b: 106). He assumes three Sanskrit cognates for the Iranian ī̆šti-. The Ved. Skt. 1iṣtí-. “impulse, acceleration, hurry, order, invitation, dispatch”,Footnote 21 while the Ved. Skt. 2iṣṭí- means “seeking, desire, wish, request”Footnote 22 (Monier-Williams Reference Monier-Williams1899: 169; Humbach, Reference Humbach1991b: 106). On the other hand, Kellens and Pirart (Reference Kellens and Pirart1990: 224) refer to another Skt. noun iṣṭi- “sacrifice, sacrificing”, which is the name of an oblation in Rigveda consisting of butter and fruits as opposed to the sacrifice of an animal or Soma (Monier-Williams Reference Monier-Williams1899: 169). Another definition derives from the Ir. verb ĪS “to own, possess; rule, master, reign” (Skt. ĪŚ) and means “command, ability”Footnote 23 (Humbach Reference Humbach1991b: 106). Since the root ĪS contains connotations related to owning and possession, then meanings like “possession, wealth, and property” are also suggested.Footnote 24

The initial vowel in the word ī̆šti- is often long (ī). A short vowel (i) is only seen in Vr.23: 1 (ī̆štīm)Footnote 25 and Yt.19: 32 (ī̆štīm) (Bartholomae Reference Bartholomae1904: 377). Etymologically, the initial vowel is expected to be a long one, so the short vowel in Avestan is probably a transmission failure.Footnote 26 Moreover, it is occasionally spelled īsti- in a few Indian manuscripts of the Avesta (for example, in K11A, Lb2) (Avestan Digital Archive 2021). This is etymologically the expected spelling for the Iranian cognate of the Skt. *īśti-. Manuscript B is observed to show the form yastīm (ADA, B8, p. 7) which would be a later “Verschlimmbesserung” by the scribes. Another explanation would be that the Indian manuscripts show a confusion between /s/ and /ʃ/ especially in the context before /t/ (Cantera Reference Cantera2014: 307).

3. The syntactic contexts of Av. ī̆šti-

3.1. Attestations based on the available evidence

Table 1 demonstrates that ī̆šti- can function as an argument or an adjunct of intransitive,Footnote 27 (mono)transitive and ditransitive verbs. However, ī̆šti- is not attested as an agent, causer, or instrument. The verbs used with ī̆šti- include: giving/taking verbs, namely give, grant, assign, withdraw, and rob; a few requesting verbs, including request, implore; and considering/contemplating verbs including consider, venerate, esteem, be appreciated. Therefore, it is alienable, desired, and contemplated. It also demonstrates that ī̆šti- has played the role of the patient whenever it is a core argument of these verbs.

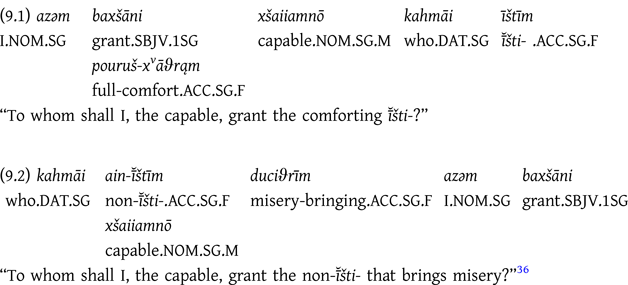

Table 1. Verbs used with ī̆šti- (arranged in OAv. and YAv. sections for comparison)

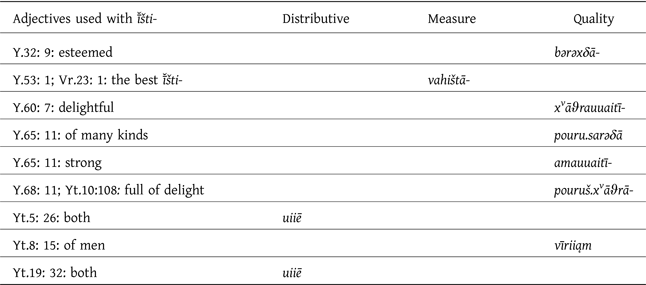

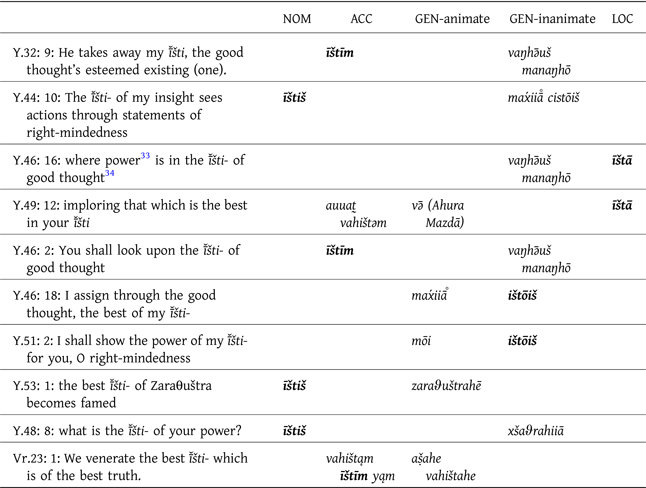

ī̆šti- is not attested in the plural form and is described with distributive, measure, and quality adjectives in the context (Table 2). The measure adjective “the best” shows a gradable entity, though it would also indicate absolute supremacy.Footnote 30

Table 2. Adjectives used with ī̆šti-

Possessive personal clitics, used with giving/taking verbs, can also indicate the beneficiary (West Reference West2011: 36). Moreover, the possessive pronouns can be used in parallel with genitive nouns, assuming similar functions (West Reference West2011: 36). The use of genitive animate nouns with ī̆šti-, especially in the case of animate arguments (Table 3), would refer to the possessors of ī̆šti-, for example, Zaraθuštra and Ahura Mazdā.

Table 3. Possessors of ī̆šti-

In a few occurrences, ī̆šti- is used with inanimate entitiesFootnote 31 in the genitive, namely good thought, insight, power, and the best truth. In example 4 (Y.48:8):

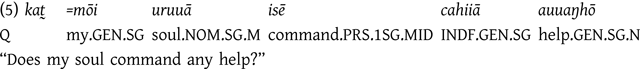

One assumption would be that using a genitive case describes an entity's attributes (West Reference West2011: 36). For example, “ī̆šti- of power” would mean that ī̆šti- is an attribute of power. It could also be that ī̆šti- takes objective genitives just as the verb ĪS governs genitiveFootnote 32 objects, thus it would mean “command over power”. In example 5 (Y.50: 1), cahiiā auuaŋhō is the object of the verb isē:

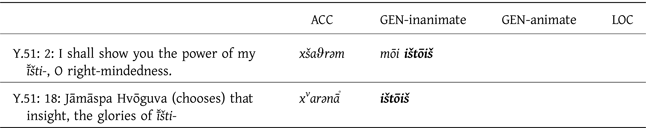

Interestingly, ī̆šti- is attested to depend on just a few nouns (Table 4), namely powerFootnote 35 and glory. It seems that in the case of “the glory of ī̆šti-”, it refers to either the domain or the source of glory.

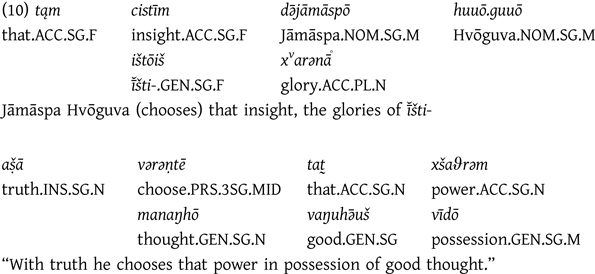

Table 4. ī̆šti- as a dependent noun

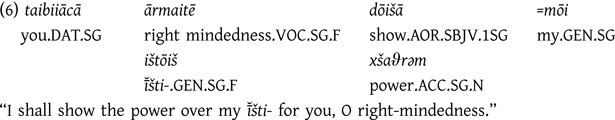

However (in the case of power), it probably indicates the realm over which the power or rule is practised (ibid: p. 39). For example, in 6 (Y.51:2) “the power of ī̆šti-”:

The co-occurring noun phrases in parallel structures (Table 5) show that in the YAv. texts, ī̆šti- is an exalted and desired possession which was requested to be granted by gods to the faithful as a worldly reward.

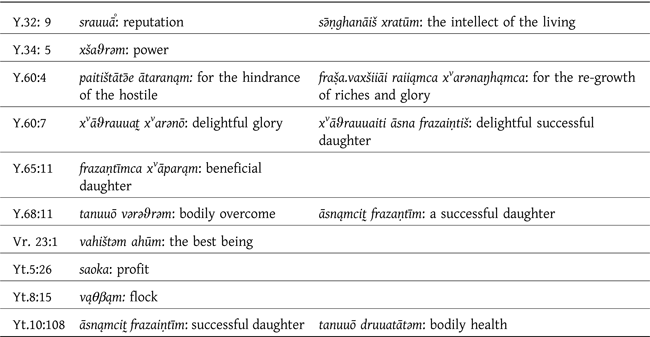

Table 5. Co-occurring noun phrases in parallel structures with ī̆šti- (arranged in OAv. and YAv. sections for comparison)

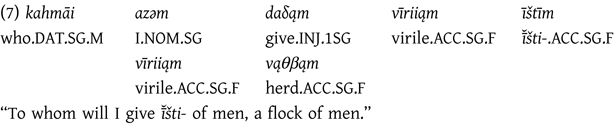

In example 7 (Yt.8: 15), “ī̆šti- of men” is followed by “flock of men”:

and in 8 (Y.65: 11) by “a beneficial offspring”:

Another point is the attestation of the concept of the non-ī̆šti- in 9.2 (Yt.10: 110) following a reference to ī̆šti- in 9.1 (Yt.10: 108). These two quotations help clarify the notion:

These two quotations (9.1 and 9.2) are a part of the two parallel inventories of things that should be granted to Mithra's worshipper(s) or taken from his non-worshipper(s). These lists include “health of the body” against “illness and heath” and “raising noble progeny” versus “slaying noble progeny”. Therefore, the “comforting ī̆šti-” seems to be semantically opposite to the “ainī̆šti- that brings misery”. Thus, ī̆šti- is a reversible concept.

According to example 10 (Y.51: 18a–b), ī̆šti- is of a more conceptual nature. The glories stemming from ī̆šti- are here used in parallel structures with insight and the power of good thought:

4. Derivatives of ī̆šti-

The adjective +īštiuuaṇt-Footnote 37 (Yt.7: 5, Ny.3: 7) “possessing īšti” derives from īšti.uuaṇt-. It is, along with other rhyming adjectives such as xštāuuaṇtəm “shiny, beautiful”, yaoxštauuaṇtəm “skilful”, saokauuaṇtəm “beneficial”, zairimiiāuuaṇtəm “having a permanent house”, used to describe the moon. The existence of the adjective composed of the noun īšti- and the possessive adjective maker -uuaṇt “possessing, having” confirms that īšti-is a possession.

5. Interim conclusion

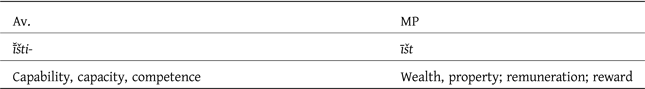

We have already considered the linguistic taxonomy of the verbs, and genitive nouns used with ī̆šti-, as well as its possessors, in the Av. texts. We also demonstrated that it has only been a patient for the verbs of giving/taking, requesting (to have), and considering/contemplating semantic groups. It is not attested to be the agent or subject of an intransitive verb, has never been attested in plural form, though it is described as having many kinds and belonging to Ahura Mazdā who can grant it to Zaraθuštra and the faithful. Therefore, ī̆šti- is an exalted alienable property of a gradable quality or absolute supremacy since it is described as strong or best. Moreover, ī̆šti- is used in expressions with inanimate entities, such as xšaθra- “power”, vohu- manah- “good thinking”, xvarǝnah- “glory”, aṣ̆a- vahišta- “the best truth”, and cistī- “insight”. These expressions can be interpreted in several ways. They can refer to ī̆šti- as the source, attribute, or domain of these entities. Insofar as the limited data is representative of ī̆šti- usage in different periods, these findings show that ī̆šti- in Avestan refers to “capability, capacity, or competence”. Therefore, the adjective īštiuuaṇt means “competent, capable”, and the reverse concept of non-ī̆šti- “incapability, incapacity, or incompetence”.

6. Middle Persian īšt

How did Middle Persian interpreters translate and understand Avestan ī̆šti-? The Avestan corpus shows 25 occurrences of the word, nine of which have no MP translations (belonging to Yt.5, 8, 10). The occurrences with a MP translation belong to VištāspYašt, Visperad, and mostly Yasna. Of the 14 occurrences in Yasna, eleven belong to the Gāthās.

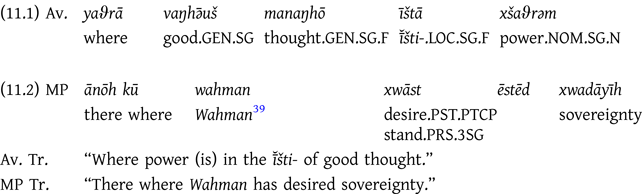

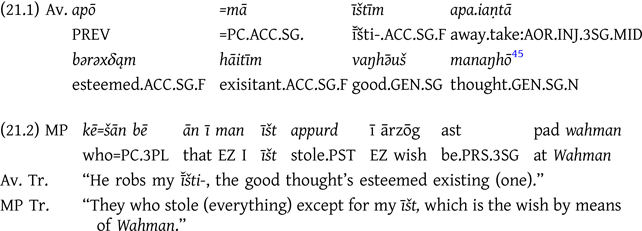

In a few examples, the Avestan noun is translated into a verb,Footnote 38 all derived from the verb xwāstan “want, desire”. It indicates that MP interpreters considered the word as a root from IŠ “want, desire”. For example, in 11 (Y.46: 16d):

Several other Avestan forms, usually stemming from the OIr. root IŠ “want, desire” are also translated into the MP verb xwāstan “want”. For example the OAv. iš́iiā (Y.48: 8.c) “desired” is translated to the MP xwāhišnīh “desiring, requiring”.

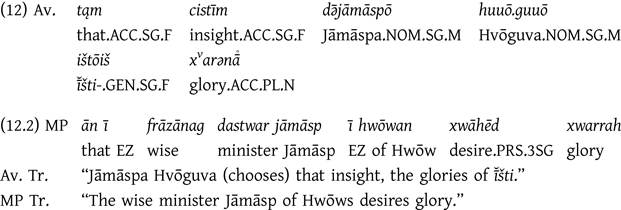

The relation of ī̆šti- and xšaθra- is expressed in periphrastic perfect xwāst ēstēd “has desired”. Thus, the intended meaning would be “sovereignty is in the desire of Wahman”. However, the verbs which appear in the MP translation of the Av. ī̆šti- differ in their time, aspect, and mood (TAM). In 12.2 (Y.51: 18), the TAM marking of the verb xwāstan is different:

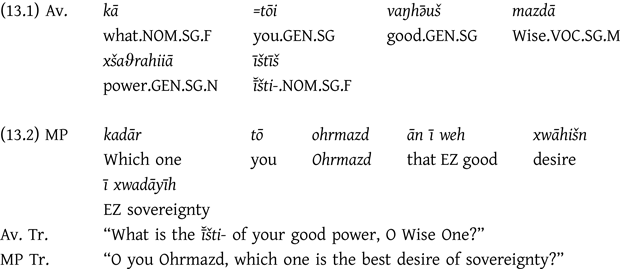

There are also occurrences in which ī̆šti- is translated into a noun stemming from the verb xwāstan “desire”. In example 13.2 (Y.48: 8), the MP text would be understood in relation to the Avestan text as seen below:

As is evident, here, ī̆šti- is translated into the noun xwāhišn “desire”. Moreover, ān ī weh corresponding to vaŋhə̄uš, which is related to xšaθra- (not ī̆šti-), while in the MP translation, ān ī weh describes xwāhišn (not xwadāyīh). The Av. word order is not followed strictly by the MP translation here.

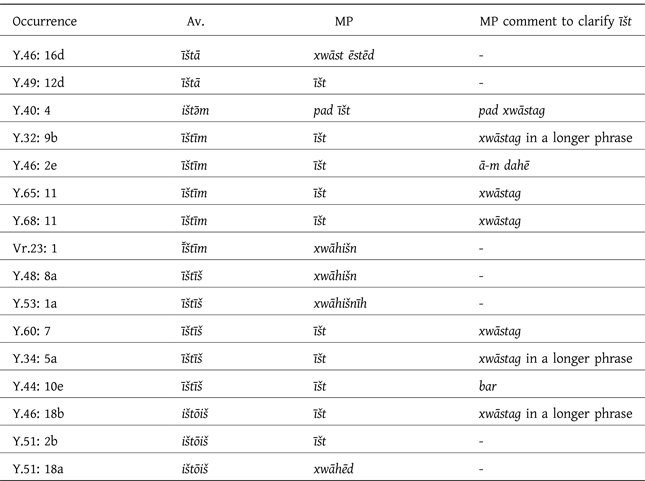

Elsewhere (Table 6), MP interpreters usually use the calque īšt in their glossing of the Avestan text and spell it with the Avestan letter ī.Footnote 40 In Zand texts, MP īšt seems to be used only as an equivalent for the Av. ī̆šti-. The only exception is in Yasna Haptaŋhāiti (Y.40: 4), where it glosses the Avestan ištəm, PPP of the verb iš- desire.Footnote 41 Zeini (Reference Zeini2020: 277–8) left MP īšt untranslated, being a learned (loan)word from Avestan scholarship, in his recent study on YH. In comments, he also refers to the occurrences of the word and correctly recognizes the semantic domain of MP īšt to be “property”, but casts doubt on its semantic detail. Finally, Zeini (Reference Zeini2020: 164) concludes that since, in the broader MP literature, īšt occurs in the proximity of sūd, then, sūd “profit”, xwāstag “wealth, property”, and bar “fruit, yield” are used interchangeably to comment on īšt without noticeably modifying its meaning. The problem with this assumption is that the word also occurs in the proximity of a few more desired possessions in Av. and MP texts, but this does not mean that they are defining the word.

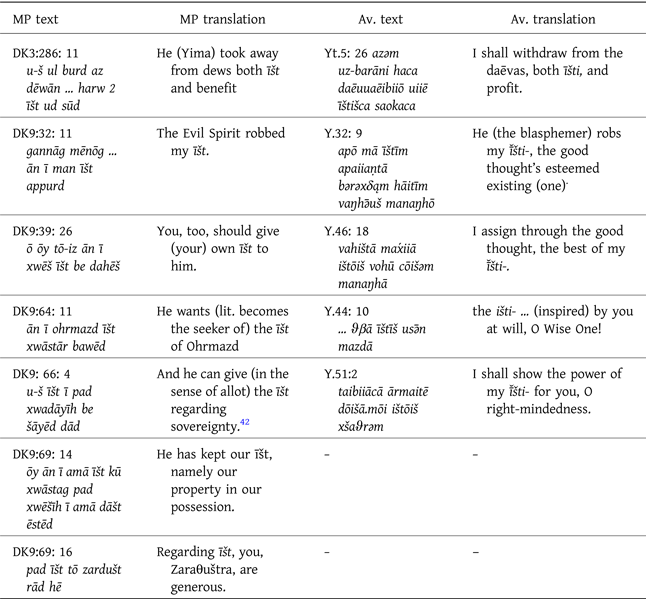

Table 6. The Av. ī̆šti- “property, wealth” and its MP translations

In addition to the direct translations of Avestan texts, īšt is also attested in the MP texts of the Dēnkard (DK), where they render interpretations of the Avestan exegeses. Therefore, īšt is another example of the words from the MP translations of the Avesta which later became a MP vocabulary item. As shown in Table 6, īšt is also frequently explained by MP xwāstag “wealth, property”. As stated above, the Zandist(s) apparently understood the word īšt to derive from the root IŠ “want, desire”. MP xwāstag (literally “wanted, desired”) also derives from the MP verb xwāstan “want”. Thence, it seems that the Zandist(s) used the original MP xwāstag synonymously with the calque īšt.

Table 7 shows the occurrences of īšt in MP texts. For the majority (five out of seven) of these quotations, it is easy to find the Av. original text since the quotations, though not a strict translation, keep the same discourse. The interesting point is about the MP quotation of the Av. Yt.5: 26, for which no Zand text has yet been found. The last two MP examples seem not to refer to any particular line in the Avesta but, instead, render a general understanding of the Avestan texts. The MP heading for the part from which these two quotations are extracted, contributes to this idea. For example, DK9: 66 starts with the heading wīstom fragard Wohuxšatr “the twentieth chapter, Wohuxšatr” which refers to Gāthā 51, traditionally called vohu-xšaθra after its two initial words.

Table 7. īšt “property, wealth” in MP texts

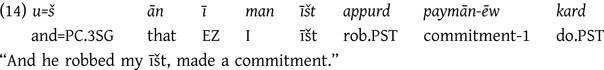

Table 8 compares Zand translations with the related MP quotations in the Dēnkard. As expected, in these quotations the viewpoint is different. Since the narrator of the Gāthās (the majority of occurrences belong to Gāthās) is considered to be Zaraθuštra, there are fewer first- and second-person pronouns and more third-person pronoun (e.g. Y.51: 2, Y.44: 10). Exceptions are when the issue concerns the hērbed and hāwišt relationship (e.g. compare the Zand and MP quotation of Y.46: 18 in Table 8) or a general/still significant issue (e.g. Y.32: 9).

Table 8. Av. originals, Zand translations, and MP quotations

There are references to the Av. texts in the MP quotations, which could not be made if the author had access only to the Zand translations and not the Avestan originals. For example, in Y.44: 10, the controversial Av. usə̄n is translated to MP hunsand hom in Zand, but to xwāstār bawēd in the MP quotation in DK9. Moreover, the author of the Dēnkard seems to have had access to the comments of the Zandist(s). For example, in Y.32: 9, the Zandist, in a comment, refers to a commitment or a treaty between the adversaries (who have robbed īšt) and the faithful for conditions under which the faithful could keep their belongings. The DK quotation uses this comment for referring to the commitment:

Therefore, it could be assumed that the author of Dēnkard had access both to the Avestan texts and the MP translations, probably in bilingual manuscripts like those that include Avestan and MP texts in the same book.

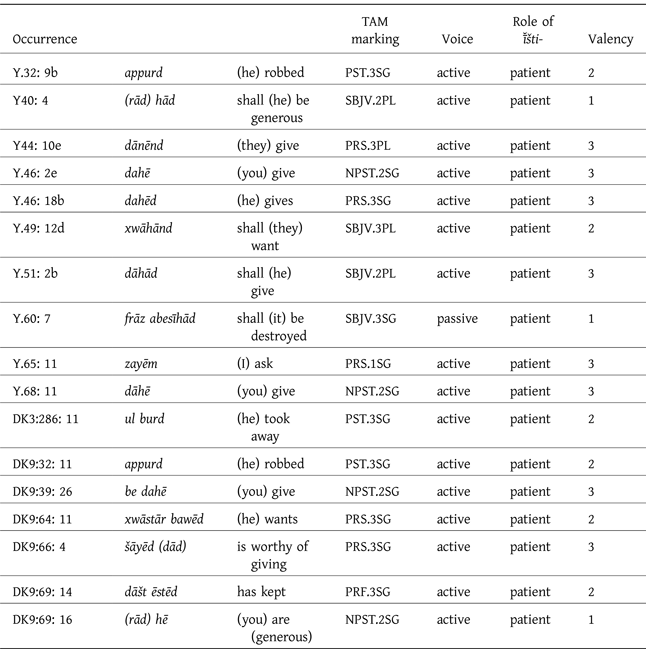

Table 9 demonstrates that MP īšt can function as an argument or an adjunct of in-, (mono)transitive or ditransitive verbs. Here again, the intransitive verbs are either copula or passive. In MP, too, īšt is never attested to act as an agent, rather usually a patient. The verbs used with īšt could be categorized as giving/taking, destroy, and request (to have) verbs. There is no trace of contemplating/looking verbs anymore.

Table 9. Verbs used with īšt “property, wealth”

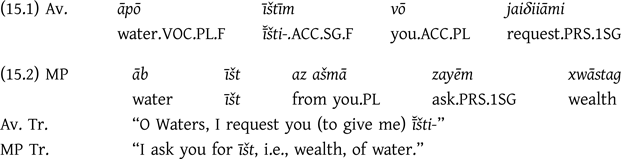

A few nouns are used with īšt, and they belong to two groups: the first consists mostly of genitive pronouns (ān ī man “that of mine”, ān ī ašmā “that of yours”, ān ī tō “that of yours”) and sometimes genitive nouns, usually animate entities referring to the possessor or the recipient of īšt (ān ī xwarrahōmand “that of the glorious one”). In contrast, the other group consists of inanimate entities and refers to the attributes (ān ī ahlāyīh īšt “the īšt of righteousness”, namely righteousness features īšt). There is also an attestation of āb īšt (Y.65: 11) in example 15.2, which seems to define the nature of the requested īšt. Although in the Av. original (15.1), apō refers to the goddess(es) of waters. Here (15.2), too, īšt is further explained by xwāstag:

As with xwāstag “wealth, property” in 15.2, comments usually clarify the meaning of the word īšt. For example, in Y44: 10 ēd ī tō īšt “your īšt” is immediately interpreted as bar “fruit, yield”. For a better understanding, let's refer to a few sentences before and after its occurrence, in example 16:

Therefore, it seems that īšt here refers to the reward given to the faithful who dedicates his wealth to religion, speaks and acts right-mindedly, and knows the end of things wisely. However, there is also probably a reference to the remuneration paid by the faithful(s) to the priest(s) as a sacrifice for their religion where (ex. 16) it refers to the increase of “my material world” and conditions satisfaction to when “they do not give me little”.

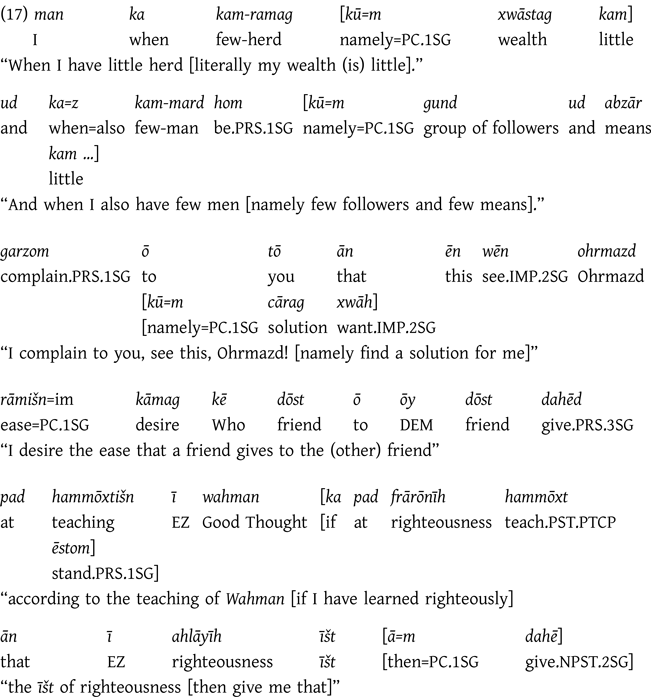

In example 17 (Y.46: 2), īšt seems to be the reward of righteousness and good thinking:

In seven occurrences of īšt in MP texts (out of ten), it is almost immediately described by xwāstag “wealth, property”. Another example is 18 (Y.46: 18b):

Regarding the two examples (17 and 18), it seems that the teachings of Wahman and ī̆šti- are associated, which should have stemmed from the Av. collocation of the two. The relation of the Av. ī̆šti-, as was explained above, should be of source-fruit nature. Similarly, in the MP translations, it is as if ī̆šti- is the reward that is dedicated to the faithful according to the teachings of Wahman.

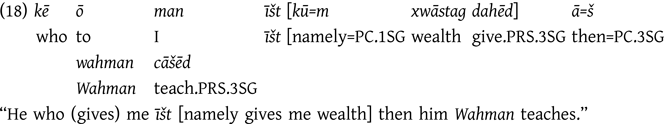

In YAv. texts, too, ī̆šti- is understood as “wealth”. In example 19 (Y.68: 11):

Thus, the interpretation of īšt in MP translations of OAv. and YAv. does not present a detectable difference and seems homogeneous throughout the Zand texts. Moreover, it seems that according to example 20 (Y.32: 9a–b), īšt is an article of the disputed property. Being once stolen by the adversaries, its ownership should be kept according to the acceptance of a particular commitment under the authority of the adversaries:

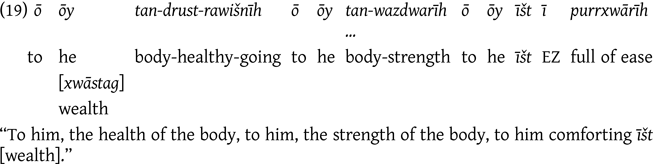

In example 21.2, it seems that ī ārzōg ast pad Wahman refers to Av. ī̆šti-, and thus again, the relation between īšt and Wahman is exposed:

Accordingly, it can be concluded that MP īšt is the reward of righteousness and will be granted to the faithful, according to Wahman.

7. Conclusion

Scholars studying the OAv. texts alone have used different translations for the word ī̆šti- in different contexts. Av. ī̆šti- has been taken to include a wide range of related meanings, from assets to ability, power, command, wish, and ritual. The noun ī̆šti- is a feminine noun that is not attested in the plural form, nor is it attested in a syntactic context in which it assumes an agentive role. In this article I have argued that the noun denotes an alienable, desired, contemplated, and gradeable concept. These findings show that ī̆šti- and its usages in Avestan refer to ability or competence. Hence, one explanation is that it derives from the IIr. verbal root *HAIS “to be able, to rule” (Cheung Reference Cheung2006: 158) and means “capability, capacity, or competence”. The adjective īštiuuaṇt then means “capable, competent”. It is how expressions like xšaϑrahiiā īštiš “the capability of power”, max́iiā̊ cistōiš īštīš “the competence of my insight”, and vaŋhə̄uš manaŋhō īštā xšaϑrəm “power (is) in the capacity of good thought”, come to light. Moreover, ī̆šti- is a reversible concept. Therefore, the reverse expression ainī̆šti- means “incapability, incapacity, incompetence”. Ahura Mazdā is invoked to grant the competence/capacity to the truthful, comforting them, and to take it away from the deceitful and leave them in misery.

In the Pahlavi version Av. ī̆šti- is occasionally translated by forms of the verb xwāstan “to want, desire”, though their TAM markings can differ and do not reflect any pattern. Otherwise, where the noun īšt is used in the translation, it is usually explained by xwāstag, which literally means “(what is) desired” and acquired the meaning “wealth, property”. The MP comments reveal that īšt is the reward in return for righteousness and good thought, which is given to the faithful. Likewise, the priest who performs the rituals and dedicates them to the divinities on behalf of the faithful is rewarded by them with remuneration, which is also called īšt. Moreover, MP translation seems to refer to a pact with the adversaries who control the faithful/ priest's property to let him own īšt. Moreover, this interpretation is further supported by a connection between the concepts of capability and wealth in Iranian languages. For instance, MP tuwāngarīh “richness, wealth”, deriving derives from the noun tuwān “might, power”. Therefore, the association of the two meanings “capability, capacity, competence” and “wealth, property” is not surprising.

The reference to Av. ī̆šti- in the inventory of the worshippers’ wishes in YAv. and its association with Good Thought in OAv. is understood differently in MP texts in so far as Good Thought is personalized in the latter texts and has acquired a mythological character. Thus, in the MP translations, īšt is granted as a reward to the faithful by Wahman.

To sum up, it has been argued here that Av. ī̆šti- means “capability, capacity, and competence”. In MP texts, the noun is reinterpreted and understood as (a rewarded) “wealth, property” “remuneration”. It is also sometimes translated to the verb xwāstan “desire, want”. Table 10 may illustrate the result of the present investigation:

Table 10. The semantic domains of Av. ī̆šti- and MP īšt

List of abbreviations

- A

Agent

- Av.

Avestan

- ABL

Ablative

- ACC

Accusative

- ACT

Active

- ADA

Avestan Digital Archive

- AOR

Aorist

- DAT

Dative

- DU

Dual

- DK

Dēnkard

- EZ

Ezāfe

- F

Feminine

- GEN

Genitive

- INJ

Injunctive

- INS

Instrumental

- M

Masculine

- MID

Middle voice

- MP

Middle Persian

- N

Neuter

- NOM

Nominative

- NPST

Non-Past

- OAv.

Old Avestan

- OIr.

Old Iranian

- OP

Old Persian

- P

Patient

- PASS

Passive

- PC

Personal Clitic

- PL

Plural

- PRS

Present

- PREV

Preverb

- PST

Past

- PT

Pahlavi Texts

- PTCP

Participle

- SBJV

Subjunctive

- SG

Singular

- ŠNŠ

Šāyist nē Šāyist

- V.

Vīdēvdād

- VOC

Vocative

- Vr.

Visperad

- Y

Yasna

- YAv.

Young Avesta