Desert and justice

In his classic book Doing & Deserving, Feinberg posed the following question: ‘What is it to deserve something? This guileless question can hardly fail to trouble the reflective person who ponders it. Yet until its peculiar perplexities are resolved, a full understanding of the nature of justice is impossible, for surely the concepts of justice and desert are closely connected’ (Feinberg, Reference Feinberg1970, p. 55). Many earlier philosophers would not have disagreed. In the Nicomachean Ethics, for instance, Aristotle wrote that: ‘… awards should be “according to merit”; for all men agree that what is just in distribution must be according to merit in some sense’ (Aristotle, 1980, p. 112), and in Utilitarianism, Mill contended that: ‘… it is universally considered just that each person should obtain that (whether good or evil) which he deserves; and unjust that he should obtain a good, or be made to undergo an evil, which he does not deserve.’

A concern for desert appears to have some deep psychological basis to it. That is to say, deliberations on what justice entails did not give rise to a concern for desert, but rather a sense of rewarding and punishing based on some conception of desert, which probably evolved naturally because of the group and individual benefits that it serves, necessarily informed discussions on justice. Indeed, some desert-driven behaviors may even transcend our own species. For example, de Waal (Reference de Waal2010) placed two monkeys in a cage that separated them with a wire mesh. Both monkeys were required to pull on a counterweighted tray in order for only one of them to reach a cup of apple slices. It was reported that the monkey that could reach the apple slices would push more of it through the wire mesh to its assistant than when it had to secure the apple slices entirely via its own efforts, and if the assistant was not rewarded as such, it was less likely to cooperate in a repeat task. One could interpret these rewards and punishments as being motivated by a basic – almost instinctive – sense of desert.

With respect to our own species, the traditional view within the field of child development psychology is that children start to relate earnings to work contributions at about 6 years of age, but over the last decade evidence has emerged that children do this from as young as 3 years, suggesting that it is almost natural for us to be driven to some degree by notions of desert. For example, Kanngiesser and Warneken (Reference Kanngiesser and Warneken2012) reported a study in which 36 three- and five-year-olds (18 of each) played a fishing game. Each child was paired with a puppet partner and both ‘fished’ for coins, which could be later exchanged for stickers. Importantly, the relative number of coins collected by each partner in a pair could be manipulated by the experimenter by ‘speeding up’ or ‘slowing down’ the puppet. The children, on receiving their sticker rewards, were able to share some of them with their puppet partner. Kanngiesser and Warneken observed that the children, on average, kept significantly more stickers for themselves when they had collected more coins than the puppet than when they had collected fewer, although it ought to be noted that very few children gave the puppet more than half of the total number of stickers available, even when the latter had collected the most coins. Selfish behavior was thus far from absent in this study, and the ability to reward according to merit to the extent that the final outcome is definitively disadvantageous to those in control of rewards probably does not develop until middle childhood, but the rudiments of a concern for desert-based rewards were evident.

Levels of desert

In most circumstances, reciprocal exchange is unlikely to be sustained in a manner that is healthy and beneficial to all involved parties unless there is, among those concerned, a perceived balance to the exchange, which is where desert often enters. For instance, if you were to give someone an espresso machine for his birthday and he later gifts you a wooden spoon for yours, then assuming that the other person is not substantially poorer than yourself, future birthday presents are either likely to return to approximate parity with respect to the value of the presents (i.e., you might buy him a fish slice next year), or the exchange will discontinue altogether. Or to give a more extreme example of negative reciprocity, in many contemporary societies, people would generally be appalled if the punishment for stealing a loaf of bread were to have one's hands cut off, because of a feeling that the perpetrator did not deserve that level of punishment for the crime committed – that is, the crime and the punishment are unbalanced (or, equivalently, the punishment does not fit the crime).

Although people seem to have some almost instinctive sense of desert, the extent to which people are perceived to be deserving of something is often an amorphous concept that may differ interpersonally, as well as across time and place, as the above-stated example of having one's hands removed for stealing food might indicate (stealing food is a more serious matter when food is generally scarce than when it is available in abundance). Even if we limit ourselves to the simplest form of reciprocity bar the instinctive attitudinal type that is common in the animal kingdom (e.g., cats licking each other) – that is, direct positive dyadic reciprocity – desert can be a malleable, complex concept.

For instance, do we prioritize our attention, and/or give most to, those who have given most to us in absolute terms, to those who have given the most relative to their own resources, to those who we know will be quick – or slow – to put a halt to their reciprocating behavior if they feel they have been slighted, or, going beyond dyadic reciprocity, to those who give the most to others quite apart from ourselves? Deliberation on the extent to which people are deserving may encompass all of these considerations and more; all potentially help us to identify, engender, and sustain the most mutually beneficial long-term reciprocal relationships. Give too much, and you risk breeding resentment (possibly in you and in the recipient) and/or enforced obligation rather than a free and fair exchange, which would not bode well for long-term, and perhaps even short-term, cooperation; give too little and the hope of a long-term reciprocal mutually beneficial relationship will likely be a nonstarter.

With respect to negative reciprocity, if the punishment is felt to exceed the crime or vice versa, there will be a prevailing sense that justice has not been served, which may lead to resentment, further retribution, spiraling retaliation, and/or a general unwillingness to engage freely in social cooperation. People may still cooperate under a cloud of fear, but fear is not conducive to mutually beneficial actions, and without mutual benefit, the cooperation is unlikely to be sustained. In short, negative reciprocity, which serves to bind groups together by deterring those who might otherwise transgress social norms, will threaten to tear groups apart if desert as a concept is not embraced, explained, and widely accepted in the shape of policies, institutions, and interventions. Public or popular opinion might, of course, often clamor for greater punishment for a misdemeanor than a deeper reflection on justice (or even common sense) will warrant. Given the complexity and malleability of desert, and the need for criminal justice systems to consider punishment, penitence, reformation, deterrence, and the like, it is likely that the scales of justice will often be considered by many to be somewhat unbalanced. To sustain a justice system, or group cohesion, or even personal relationships, it is important to explain clearly the rationale for why a particular punishment is deserved, and then hopefully, over time, a compromise might be reached if there is initial disagreement pertaining to this explanation. Both sides to the exchange have to be satisfied that the punishment fits the crime – that desert is given its proper due.

A taxonomy of blame

When considering desert in relation to punishment (and, indeed in relation to reward, but for ease of exposition, I will focus on negative reciprocity here), it is important to recognize that people often act not entirely through volition but due to the force of necessity. For instance, when people face extreme scarcity and are in great need, they may face little choice than to act egoistically if they are to survive. Consequently, our response to a person who steals a loaf of bread, for example, is likely to differ if that person is starving than if he has ample food supplies (and, indeed, will differ if we are starving than if we have ample food supplies). Thus, we ought to distinguish between actions over which a perpetrator is morally responsible and can therefore be blamed fully, and actions over which it is harder to attach blame. As Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1970, p. 117) notes: ‘… general rules must list all crimes in the order of their moral gravity, all punishments in the order of their severity, and the matchings between the two scales. But the moral gravity scale would have to list as well motives and purposes, not simply types of overt acts, for a given crime can be committed in any kind of “mental state,” and its “moral gravity” in a given case surely must depend in part on its accompanying motive.’

In order to judge the blameworthiness of an action, one ought to distinguish between actions that are causal and actions that are attributive. That is, in order to fully assign blame for an unwanted outcome, it is insufficient to proclaim that an action caused a harm; one must also attribute an objectionable aspect of the action directly to the harm that has occurred. Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1970, pp. 196–197) relates attributive actions to what he calls the triconditional analysis, consisting of (1) the fault condition; (2) the causal condition – that is, that the act was a cause of the harm; and (3) the causal relevance condition – that the faulty aspect of the act was its causal link to the harm. According to Feinberg, the causal relevance condition goes a long way toward discerning whether someone's action is fully blameworthy (or praiseworthy, if we are in the domain of positive actions).

Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1970, pp. 207–208) illustrates his argument with the following lively scenario: ‘Consider … the case of the calamitous soup-spilling at Lady Mary's dinner party. Sir John Stuffgut so liked his first and second bowls of soup that he demanded a third just as Lady Mary was prepared to announce with pride to the hungry and restless guests the arrival of the next course. Sir John's tone was so gruff and peremptory that Lady Mary quite lost her composure. She lifted the heavy tureen with shaking arms and, in attempting to pass it to her intemperate guest, spilled it unceremoniously in the lap of the Reverend Mr. Straightlace.’ In this example, one might contend that the causal relevance condition suggests that Sir John's gruffness unsettled Lady Mary, which consequently caused the accident. Sir John is thus to some extent to blame for soiling the reverend's trousers. If Sir John had instead politely requested more soup, although we might still judge him at fault for his gluttony, the absence of any gruffness to his tone might mean that we would be less inclined to blame him for the soup spillage. As Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1970, p. 222) notes: ‘… if the harmful outcome was truly “his fault,” the requisite causal connection must have been directly between the faulty aspect of his conduct and the outcome.’

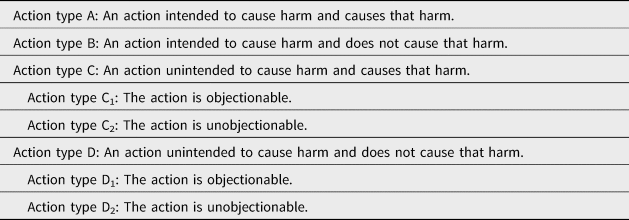

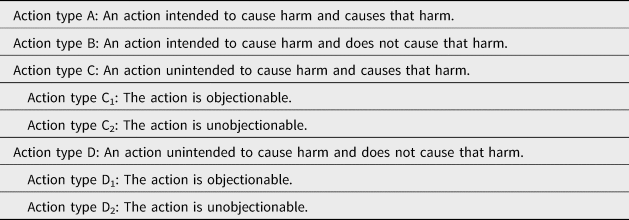

However, although Sir John's gruffness may have caused the soup to spill, he did not intend for that outcome to occur. Intending the bad outcome to occur is thus not a prerequisite for some deserved degree of blame, but intending as such may scale up the blame that the perpetrator merits. The notion of intention thus allows us to construct a taxonomy, summarized in Table 1, of the degree to which blame is merited for an action that often – but not always – leads to a harmful outcome.

In Table 1, Action type A, where a person intends to cause harm and the harm occurs, is the most blameworthy. This would be the case, for example, if Sir John, displeased with Lady Mary's reaction to his request and with the Reverend Mr. Straightlace's sanctity, had deliberately pushed the tureen from her hands and into the latter's lap. Action type B occurs when there is a similar intention to harm, but for whatever reason, the intended harm does not occur. For instance, Sir John attempts to deliberately push the tureen in the direction of the Reverend Mr. Straightlace, but stumbles, falls back into his chair, and no soup is spilled. Sir John's intentions are still blameworthy, but since no damage occurred, Action type B is not as blameworthy as Action type A.

Action type C – unintended harm-causing actions – can be broken down into two subtypes, C1 and C2, the first of which is reflected in Feinberg's (Reference Feinberg1970) original Sir John scenario summarized earlier. Sir John did not intend to spill the soup, but in the original scenario his rude demeanor flustered Lady Mary, which may have contributed to her dropping the tureen. His gruff behavior was objectionable – Action type C1 – and he is thus blameworthy to a degree. If he had politely asked for more soup, we have an example of Action type C2: his demeanor is unobjectionable and he did not intend for the soup to be spilled, but his requesting (possibly too much) soup did contribute to the tureen being dropped, and thus he is perhaps still somewhat blameworthy, but not as blameworthy as in Action type C1. In this respect, incompetence might also fall under the objectionable label, which may be a reason why politicians in several countries were viewed as considerably blameworthy for the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic, even though they did not intend what many have perceived as avoidable harms to occur (alternately, an unintended harm that is the consequence of a person acting upon a basic need may warrant an unobjectionable label). In Action type C2 compared with Action type C1, the causal relevance condition has been weakened. Whether Action type B is more blameworthy than Action type C or vice versa depends upon the trade-off between intentions and outcomes (i.e., B has worse intentions and C has worse outcomes). On a population level, this is likely to be an empirical question, but for me, in terms of assigning blame, an intention to harm (even if the harm is not realized) is worse than an unintentional realized harm.

Finally, Action type D, where there is no intention to cause a harm that is not in any case realized, is of course not blameworthy at all, but this too can be broken down into two subtypes, D1 and D2, where in the former the person's behavior is otherwise objectionable and in the latter it is not. In terms of Sir John and the tureen, D1 and D2 are identical to C1 and C2 with the important exception that the soup is not in fact spilled. The only reason for differentiating between D1 and D2 here is not to apportion blame, but to recognize that those that commit Action type D1 (compared to D2), in committing more strongly Feinberg's (Reference Feinberg1970) fault condition, are placed at a greater risk of satisfying the triconditional analysis if a relevant harm was to occur in the future. One also might want to avoid inviting such people to dinner parties (or, indeed, to choose to cooperate with them in other situations).

This attempt at identifying different levels of deserved blame informs the debate on what might be the correct application of negative reciprocity, and extends, in its mirror image, to the identification of deserved credit in informing positive reciprocity. For instance, an intention to benefit someone that is realized as an outcome would surely deserve some consideration of a return in kind. In the positive domain, Action type C1 might be that the action is welcome, and Action type C2 that the action is neutral. For example, if Sir John was so agreeable toward Lady Mary at the dinner table that he relaxed her to such an extent that she later beat everyone at billiards, Sir John might deserve some credit for her victory. If the same were to occur except that she was not undefeated at billiards, we would have the positive mirror image of Action type D1: Sir John would deserve no credit for the billiard victory because the victory did not happen, but his agreeable nature over dinner might still serve as a signal that he is a person with whom one might wish to cooperate/reciprocate in the future.

Although it might not always be easy to discern intentions nor link intentions directly to outcomes, this discussion is thus relevant when considering what might be a proportionate response to others’ actions in both the private sphere of people's lives and in informing the design of public policy. Overall, it is clear that when it comes to considering the notion of desert – that is, when it comes to deciding with whom to reciprocate and by how much – a person's intentions toward others and the outcomes experienced by those others both matter. Moreover, when considering desert, a person's intentions toward themselves may matter too.

The deserving poor

Rawls (Reference Rawls1999) argued that if each of us was unaware of our position in the world – that is, if we were placed behind his so-called veil of ignorance – then out of self-interest we would choose to focus our attention on improving the situation of those who are the worst off, in part because for all we know, we could be among them. The argument is that a proper consideration of justice would preclude the consideration of our own positions, tastes, and life experiences (etc.) when making a judgment about how society ought to be organized; that the scenario focusses our minds on how we would wish to be treated by others if we were in unfortunate circumstances, and leads us to treat others in that same way. Thus, justice, in this theory, equates to maximizing the minimum: maximin.

However, the world that we live in is of course unaligned with Rawls's transcendental proposition. The success and sustainability of policy interventions and institutions depend upon how people react to them in reality. For that, we must consider people's perceptions of how to organize society when their own (and, to a degree, others’) positions, tastes, efforts, characters, and life experiences (etc.) are known to them – that is, when the veil of ignorance is lifted. It is of course possible – even likely – that many would still opt for a maximin policy direction (or at least for a direction that helps the worst off to some extent), and for a host of reasons, including the reputational benefits that may be garnered from signaling as such and even pure altruism. However, many others might demand an indication that those at the bottom deserve any assistance that is directed towards them.

As noted by Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1970), rewards and punishment may be given in response to gratitude and resentment, and many might feel gratitude towards those who benefit from public programs if they offered something tangible in return, assuming of course that they are able, which could in turn better ensure the continued support for and sustainability of those programs. This takes us back into the realm of the desert-based arguments discussed earlier (i.e., desert in relation to the intentions and outcomes directed at others). For example, a structure could be put in place for people in receipt of welfare to volunteer to undertake some hours of public works each week if they are physically and mentally able, and the total number of voluntary hours committed could be widely disseminated on a weekly or monthly basis. As a form of conditional cash transfer, people in receipt of welfare could alternately be required to undertake such work for them to continue to receive support, which may still serve as an indicator of desert, even though a nonvoluntary requirement might breed resentment. Although the notion of expecting, or even requiring, able-bodied people in receipt of welfare to offer something tangible back to society while they are in receipt of publicly financed benefits will be unpalatable to some, a refusal to work if one is able in such circumstances is arguably a form of free riding – or egoism – that can damage the groups of which we are all a part.

However, Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1970) also contends that rewards/benefits and punishments/penalties may be given in recognition that someone has done something good or bad, without any gratitude or resentment attached. Here, there is no link between gratitude and desert. Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1970, p. 70) states, for instance, that: ‘When the father paid his son a quarter, he acknowledged his son's achievement without necessarily feeling any joy, gratitude, or any other emotion.’ This argument can be extended to more profound domains where people have done ‘good’ (or not done ‘bad’) to themselves. For instance, if it is perceived that an individual is personally responsible for his misfortune, then many might take the view that he is less deserving of assistance than if his misfortune is beyond his control. This type of scenario is sometimes discussed in relation to the prioritization of public healthcare resources; that is, if someone suffers ill health, can we make a case that he ought to be a greater priority if his misfortune is the result of genetics or accident than if it is the consequence of his own personal lifestyle choices [e.g., see Le Grand (Reference Le Grand1991)]?

Of course, it is unlikely that many of those who adjudge people to be undeserving according to the above criteria would withhold assistance entirely (not least because they recognize that recipients of assistance might feel entitled to public sector services that they have contributed to financially, and also identifying exactly what has caused a person's misfortune may often be impossible), but if one does not account for personal responsibility, then the emphasis may shift somewhat from desert to charity, from reciprocity to pure altruism. Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1970, pp. 75–76) makes the same point when he writes: ‘When a person suffers a loss, it may be the fault of another person or it may be no one's fault … the nature of desert differs in the two cases. There is, however, a third possibility: the loss or injury may be his own fault. In that case, though he may well be entitled to help, we should be loath to say that he deserved it; for we do not as a rule compensate people for their folly or indolence, and even when we do, it is not because we think they deserve it. Herein lies the difference between helping a person out of a jam simply through charitable beneficence and giving him aid he deserves … There is nothing pitiable about a person who deserves help.’

Feinberg thus suggests that there is something pitiable about a person who is helped through charity. If welfare and other forms of publicly provided benefits are generally perceived as charity – as pity-driven acts of pure altruism – rather than as being deserved, this may have implications with respect to the size and sustainability of the assistance given. Feinberg (Reference Feinberg1970, p. 87) contended that: ‘… desert is a moral concept in the sense that it is logically prior to and independent of public institutions and their rules, not in the sense that it is an instrument of an ethereal “moral” counterpart of our public institutions,’ and earlier in this article, I presented evidence that suggests that people, probably from a very young age, are indeed driven by notions of desert. If one wants to secure the best chance that substantive welfare programs will exist into the future, it is a matter of sensible strategy to design them so that it is clear that the people whom they benefit are, as far as is possible, seen as deserving.

Conclusion

I have addressed three notions of desert in this article, two of which are associated with people's intentions and outcomes towards others and the other of which is associated with people's intentions towards themselves. Specifically, they are that people: (1) deserve something positive for intending/producing something good for others; (2) deserve something negative for intending/producing something bad for others; and (3) deserve something positive for intending to prevent something bad for themselves. I contend that desert, and the associated concept of reciprocity, are stronger human motivational forces than pure altruism, and that the strength and sustainability of public sector services and welfare systems (not to mention our private relationships and collaborations) may depend upon a broad acceptance of this argument.