Deliberative citizen forums (DCFs) are increasingly being implemented around the globe, with a recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2020) report even speaking of a ‘deliberative wave’. Representing a variety of dialogical participatory procedures where diverse citizens discuss pressing policy issues with the possibility to shape public decisions, they are frequently perceived as highly appropriate institutional tools to fight the ‘crisis of democracy’ marked by increasing levels of political disenchantment, feelings of ‘non-ownership’ (Lafont et al. Reference Lafont2021) and the rise of populist parties.

Empirical research does show that DCFs are conducive to high satisfaction among participating citizens who learn and change their opinions (see, for example, Suiter et al. Reference Suiter2016), reduce polarization (see, for example, Grönlund et al. Reference Grönlund2015) and strengthen citizens' faith in democracy (see, for example, Boulianne Reference Boulianne2019). Moreover, a growing body of research finds that DCFs can also have positive effects on non-participating citizens, especially by providing them with information and recommendations to make informed political choices (see, for example, Már and Gastil Reference Már and Gastil2020). Drawing on these positive results, some scholars (and activists, for example, Extinction Rebellion) advocate institutional reforms that would increase the decision-making power of DCFs in the political system. The suggestions range from vesting them with the authority to make binding decisions (Buchstein Reference Buchstein2019), to ‘legislation by lot’ (Gastil and Wright Reference Gastil and Wright2019) – which would replace or supplement second chambers with citizen panels (van Reybrouck Reference Van Reybrouck2016) – to even more radical concepts, such as ‘open democracy’ (Landemore Reference Landemore2020), which envisions replacing legacy institutions with DCFs.

However, the use of DCFs has sparked criticism from democratic theorists. Critics argue that when vested with strong authority, DCFs would reduce rather than increase democratic legitimacy (Lafont Reference Lafont2019; Parkinson Reference Parkinson2006). Non-participating citizens will never know whether recommendations or decisions made by their deliberating peers will be aligned with their own interests, values and policy objectives. Consequently, vesting DCFs with strong authority would imply ‘blind deference’ on the part of non-participating citizens (Lafont Reference Lafont2019). According to Lafont, ‘blind deference’ violates principles of democratic self-government and would prevent the acceptance of decisions made by DCFs.

In this letter, we provide new evidence to inform debates on the actual role that DCFs should play in our democracies, with a particular focus on the considerations of ‘disaffected’ citizens. We ask not only whether citizens currently support the use of DCFs (see Bedock and Pilet Reference Bedock and Pilet2020; Jacquet et al. Reference Jacquet2022; Pilet et al. Reference Pilet2020), but also take DCFs as a given institutional practice and ask how DCFs must be designed in order to solicit support among (different strata of) non-participating citizens. We present results from a conjoint experiment with 2,039 respondents in Germany. A conjoint experiment identifies the attributes of hypothetical scenarios (for example, DCFs) that provoke positive or negative evaluations (see, for example, Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller2014). Our experiment improves on the existing studies with a similar methodological design (Christensen Reference Christensen2020) in two major ways.Footnote 1 First, it considers various authorization mechanisms and a much wider variety of institutional design elements that are crucial from both theoretical and practical perspectives (see, for example, Curato et al. Reference Curato2021) in connection with issue characteristics, outcome favourability and heterogeneous citizen preferences. Secondly, it uses a large and representative sample, while simultaneously addressing the problem that most citizens know little or nothing about DCFs. To this end, respondents were provided with an information package familiarizing them with various institutional designs of DCFs, as well as with arguments for and against crucial design elements (see Online Appendix A1).Footnote 2

Addressing the claims of DFC both enthusiasts and critics, we present a nuanced argument. Based on citizens' individual assessment of the status quo, namely, whether they think that the political system is functioning satisfactorily (or not), we assume that citizens' preferences for DCFs are driven by different sets of considerations. If they think that the legacy institutions of the representative system are basically responsive to their interests and viewpoints, then they are generally sceptical of novel institutions, such as DCFs, and assign them only subordinate or secondary roles in political decision making. However, if they think that legacy institutions are failing them, then they more open to empowered roles for DCFs.

First, against enthusiasts of DCFs, we argue that especially in political systems where citizens perceive the system as basically responsive, DCFs may suffer from a generic legitimacy gap, not only because they are novel institutions (with which most citizens have no experienceFootnote 3), but also because they are neither fully participatory nor authorized and formally accountable (see, for example, Lafont Reference Lafont2019; Parkinson Reference Parkinson2006). As a consequence, citizens in general will grant DCFs only a constricted role in decision making. We expect citizens' legitimacy concerns to increase when DCFs are vested with strong authority and when they are decoupled from the legacy institutions of the representative system (privileging, for example, forums initiated from the bottom up and composed of citizens only). Moreover, we assume that citizens call for extra provisions (namely, descriptively representative composition via random selection, a large size and clear majorities for outputs) when such novel bodies are authorized to shape political decisions. Besides institutional design elements, we expect substantive considerations to enter into the legitimacy equation of citizens. First, we assume that legitimacy perceptions hinge on issue types. Following the theoretical literature, we expect complex technical issues with a long-term perspective to be associated with more positive perceptions of legitimacy, as citizens may think that current institutions are either corrupted by vested interests and have failed to produce adequate solutions or have not yet addressed them (see MacKenzie and Warren, Reference MacKenzie and Warren2012). Conversely, we expect salient issues to be associated with more negative perceptions of legitimacy, as non-participants may think that their deliberating fellow citizens – with whom they have no accountability relationship – may not adequately represent and defend their interests, values and policy objectives (see Lafont Reference Lafont2019). Finally, following an established finding from the literature (see, for example, Esaiasson et al. Reference Esaiasson2019; Marien and Kern Reference Marien and Kern2018), we expect that outcome favourability strongly matters: the less the outcomes of a DCF correspond to respondents' own policy preferences, the less positive their evaluation of DCFs (and vice versa).

Second, against critics of DCFs, we argue that ‘disaffected’ citizens may have very different views on what roles DCFs should play in democratic systems. We focus on four groups of ‘disaffected’ citizens: ‘dissatisfied’ citizens, who share negative attitudes towards current democracy; citizens with low ‘external efficacy’, who think that the political system is responding poorly to their concerns; ‘stealth’ citizens, who favour effective and efficient decision making but think that the current system is corrupt; and ‘populist’ citizens, who think that current politics bypasses ordinary citizens and stress the unfiltered will of the people. Based on previous research (Goldberg et al. Reference Goldberg2020; cf. Zaslove et al. Reference Zaslove2020) and drawing on the argument that citizens include their status quo perceptions of political decision making, we expect these types of citizens to want something else from democracy and to prefer any alternative to the current representative system. As such, disaffected citizens may view DCFs as a possibility to get rid of unloved legacy institutions, which they think have served their interests badly (see Werner Reference Werner2020). Consequently, we expect ‘disaffected’ citizens to be much more open to a strong authority for DCFs and to care less about extra provisions. By the same token, they may also be more likely than other citizens to prefer full decoupling from legacy institutions (see also Kuyper and Wolkenstein Reference Kuyper and Wolkenstein2019).

Data, Experimental Design and Measurements

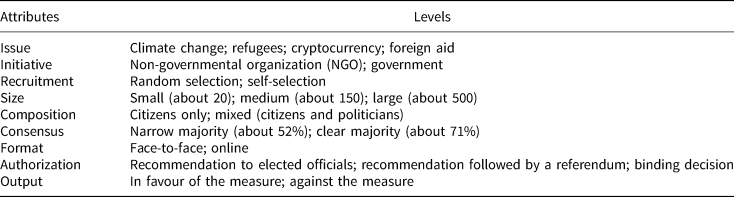

We conducted a conjoint survey experiment with 2,039 German residents aged 18 and older in December 2020. Our data come from a quota sample administered through YouGov that was weighted by age, gender, education and region, such that the weighted sample is representative of the German population. Conjoint experiments are particularly attractive because they allow for estimating several effects simultaneously without having to observe all possible combinations of attributes (see, for example, Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller2014). The conjoint design included nine attributes, with two to four attribute levels (see Table 1). The attribute values were fully randomized, allowing us to estimate the causal effects of each attribute on the probability of preferring a DCF. Additionally, we randomly assigned the attribute order for each respondentFootnote 4 to reduce primacy and recency effects. Finally, the design allows us to estimate subgroup preferences, that is, interactions between respondent characteristics (for example, dissatisfaction) and design attributes (see Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015, 535). We employed a choice-based conjoint design where respondents were randomly presented with six comparisons. For each comparison, respondents were asked both to choose their preferred scenario (choice outcome) and to assess each scenario (rating outcome) on a scale ranging from 1 (‘I do not like the citizen forum at all’) to 7 (‘I like the citizen forum very much’). The average approval score was 4.25, suggesting that respondents tend to perceive DCFs as moderately (but not overwhelmingly) positive. The binary choice outcome variable is our main quantity of interest, which equals 1 if the DCF is preferred and 0 otherwise (see Online Appendix A2). In addition, we reran analyses for the rating outcome as a robustness check (See Online Appendixes B1 and B2). Prior to the conjoint experiment, all respondents were presented with a short video on DCFs and screens with arguments on various design features. When answering the conjoint questions, respondents also had the opportunity to access a glossary (pop-up window) with information on the design features (See online Appendix A1). In addition to the conjoint experiment, the survey contained key covariates, such as political attitudes, policy preferences and socio-demographics.

Table 1. Institutional design features of DCFs

We assess the average marginal component effects (AMCEs) of each attribute (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller2014). AMCEs can be interpreted as the average differences in the probability of preferring DCFs when comparing two different attribute values (for example, random selection versus self-selection), where the average is taken for all combinations of the other attributes (see Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller2014).

We used standard items for political satisfaction, external efficacy, stealth democracy and populism to measure political disaffection (see Online Appendix A4). Finally, outcome favourability was calculated by comparing respondents' preference for a policy measure with the randomly assigned output of the conjoint exercise (see Online Appendix A3). While AMCE analyses are the main vehicle for causal interpretations, Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper2019) warn that using AMCE analysis for descriptive purposes can be misleading for subgroup analysis. As a robustness check, we additionally estimated marginal means for subgroup preferences (see Online Appendix B2).

Analysis

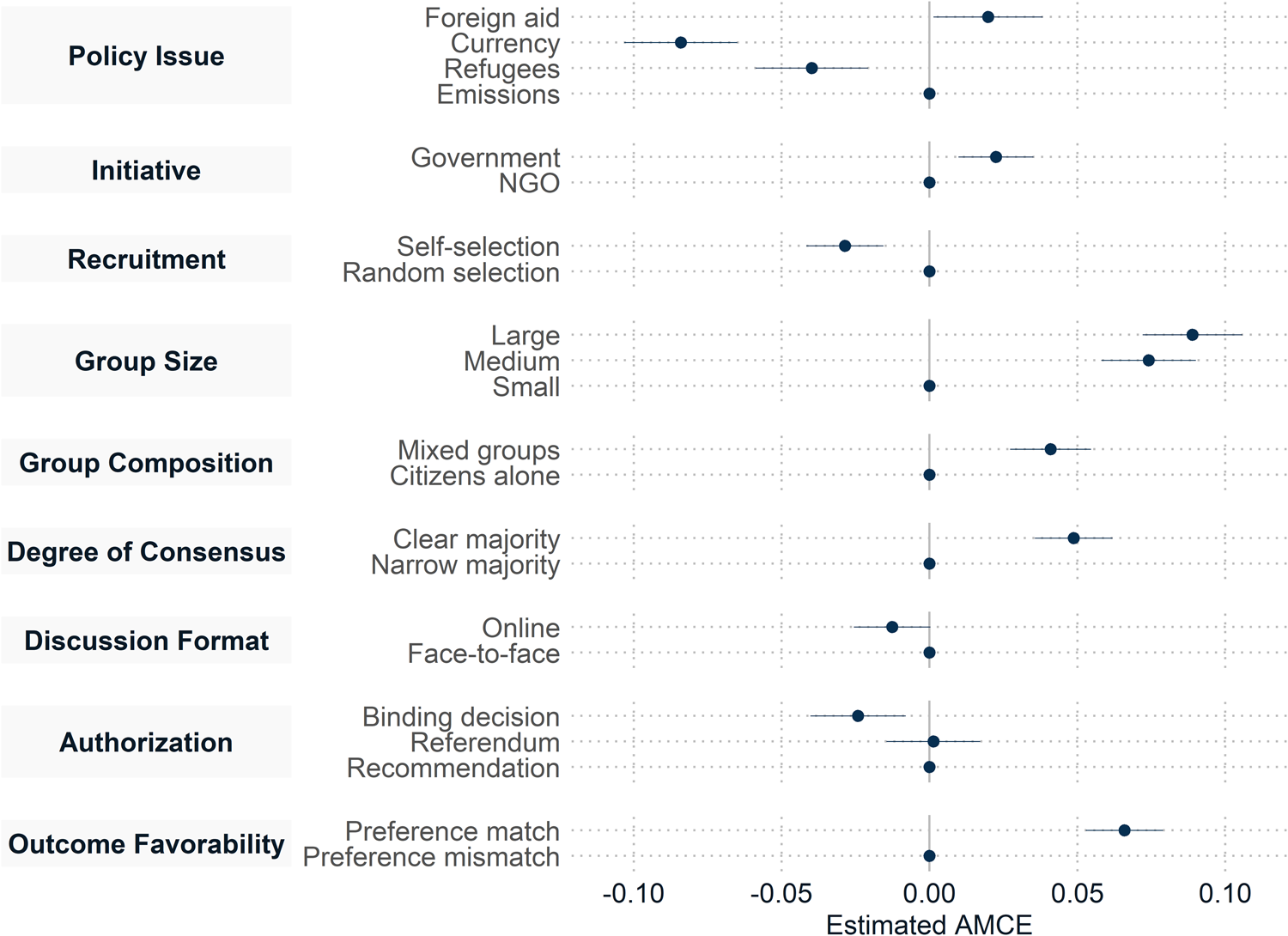

We present the findings in two steps: first, we refer to a benchmark model including all respondents; and, secondly, we examine subgroup differences for disaffected citizens. Figure 1 shows the effects of authorization mechanisms, design elements, issue types and outcome favourability on support for DCFs. The dots with 95 per cent confidence intervals denote the effects of a set of attribute values compared to the reference categories.

Figure 1. Effects of DCF attributes on support.

Note: Benchmark model for all respondents. Standard errors clustered at the individual level to take into account that each respondent made several comparisons. N = 24,468 (2,039 respondents × 12 scenarios). Effects are measured in percentage points.

In sharp contrast to advocates calling for the empowerment of DCFs, most respondents dislike decisive roles for DCFs.Footnote 5 Rather, they prefer DCFs with recommending force that precede actual decision making, advising both public officials (recommendations to elected officials) and citizens (recommendations followed by a referendum). Moreover, they favour coupled DCFs, namely, government-initiated formats composed of both citizens and politicians.Footnote 6 Turning to design questions regarding DCFs, as expected, most respondents demand extra provisions. Respondents clearly prefer sortition to self-selection, larger groups and recommendations backed by a clear majority.

Next, support for DCFs also hinge on issue characteristics and substantive considerations. Our expectations regarding technical and salient issues are not fully corroborated, however. Respondents see the non-technical/less-salient issue (foreign aid) and the technical/salient issue (measures to reduce emissions in the context of climate change) as particularly apt for DCFs, whereas their support for DCFs decreases for the non-technical/salient issue (refugees) and especially the technical/less-salient issue (cryptocurrency).Footnote 7 It seems that there is some idiosyncrasy to the issue dimension and future research may need to come up with different issue specifications. One explanation could be the degree of complexity, with non-participants considering participants of DCFs to be more qualified to discuss a slightly less technical issue (emissions) than a highly technical one (cryptocurrencies). The effect for outcome favourability conforms to our expectations: DCFs are about 6.5 percentage points more likely to win support when the output corresponds with the respondent's own policy preference. Together with large groups, outcome favourability represents the most important attribute (see also Online Appendix B1).

In sum, the findings reveal that most respondents prefer non-empowered and coupled DCFs with purely advisory roles and the collaboration of legacy actors, while simultaneously demanding extra provisions that make DCFs more representative and inclusive.

In a second step, we focus on subgroup differences between various types of ‘disaffected’ citizens. As a reminder, we argued that disaffected citizens might be more supportive of (empowered) DCFs because they feel disconnected from the current system. Intriguingly, and contrary to our assumption, both dissatisfied citizens (M = 4.16) and citizens with low external efficacy (M = 4.12) rate DCFs slightly more negatively than satisfied citizens (M = 4.36) and efficacious ones (M = 4.37). However, stealth citizens (M = 4.37) and populist citizens (M = 4.38) are slightly more positive towards DCFs than non-stealth citizens (M = 4.18) and non-populists (M = 4.12).Footnote 8 All reported mean differences are statistically significant (p < 0.001) (see Online Appendix A2). In line with Webb (Reference Webb2013), this suggests that ‘disaffected’ citizens are not a uniform group either.

The picture becomes unambiguous, however, once we look at the evaluations of design elements of DCFs. Figure 2 shows differences in effect sizes for ‘disaffected’ citizens in comparison with ‘allegiant’ citizens.Footnote 9 Difference plots can be interpreted as the estimated difference in effect sizes for the main group (disaffected citizens) compared to another group (allegiant citizens). As expected, the preferences of ‘disaffected’ citizens differ from those of ‘allegiant’ citizens. First, ‘disaffected’ citizens are more open to strong authority for DCFs and decoupling from legacy institutions. Specifically, compared to ‘allegiant’ citizens, all types of ‘disaffected’ citizens were more likely to choose scenarios that included binding decisions and citizen panels composed of citizens only. It should be noted, however, that this does not mean that they are generally in favour of empowerment and decoupling; in fact, they are mostly indifferent vis-à-vis these design elements (see Appendix B3). Secondly, they also care slightly less about extra provisions compared to ‘allegiant’ citizens, even though the effects are less clear than expected (with only size and majority producing differences). Moreover, again, there are differences across different types of ‘disaffected’ citizens: dissatisfied citizens and citizens with low external efficacy care less about clear majorities than stealth and populist citizens. Alternatively, citizens with low external efficacy tend to prefer citizen-initiated DCFs and – similar to populist citizens – dislike online formats. Group size, in turn, seems to play less of a role for stealth citizens compared to non-stealth respondents.

Figure 2. Differences between allegiant citizens and subgroups of disaffected citizens.

Note: Effects show the increase/decrease in the probability of choosing a scenario for a particular attribute level relative to its baseline level for disaffected citizens minus the probability of choosing a scenario for allegiant citizens for the same attribute level relative to its baseline category. Reference categories not shown.

Finally, when it comes to issue characteristics and substantive considerations, there are very few differences between ‘disaffected’ and ‘allegiant’ citizens. Outcome favourability matters equally for both groups of citizens, indicating that the substantive considerations of disaffected citizens might equalize or even trump their ‘instrumental’ considerations (getting rid of unloved legacy institutions).

We have run some robustness tests. First, we reran all analyses with rating outcome variables, as well as models using marginal means estimations (see Online Appendixes B1–B3). Secondly, the substantive results are more pronounced for respondents who have engaged with the conjoint items longer than the median (see Online Appendix B4). Not only is this indicative of the need for citizens to be sufficiently familiar with DCFs in order to make proper assessments, but it also strengthens our overall conclusions.

Discussion

DCFs increasingly populate the political landscapes around the globe and are frequently seen as almost ‘magic’ tools for fighting the ‘crisis of democracy’. However, our results from a conjoint experiment with German citizens lend more support to DCFs' critics, challenging notions of the strong ‘empowerment’ of DCFs. We find that citizens in general want DCFs to be constricted: non-empowered (limited to an advisory role), coupled (collaborating with legacy actors) and complying with extra provisions, namely, having descriptively representative composition via random selection, large size and clear majorities for recommendations. However, ‘disaffected’ citizens – the major focus of debates about the ‘crisis of democracy’ – grant DCFs a more empowered role. Compared to ‘allegiant’ citizens, they are less likely to oppose DCFs making binding decisions and more likely to disconnect them from legacy institutions. However, this finding should be taken with a grain of salt: on the one hand, a greater openness towards empowerment and disconnection does not mean that disaffected citizens are generally in favour of DCFs making binding decisions or being fully decoupled from legacy institutions (our data show that they are mostly indifferent vis-à-vis these design elements); on the other hand, support for DCFs among ‘disaffected’ citizens quickly decreases when DCFs decide against their substantive policy preferences.

Overall, our findings suggest that recreating feelings of ‘ownership’ over the democratic process via DCFs might turn out to be a rockier road than many advocates of DCFs have imagined. Yet, it might be speculated that when levels of disaffection in the citizenry rise and the legacy institutions of the representative system fail to realize essential democratic goals (such as responsiveness), more empowered institutional innovations might be more acceptable to citizens as a way of bringing political systems back to a ‘pragmatic equilibrium’, where democratic goals are matched by the institutional framework (Fung Reference Fung2007). However, in countries like Germany, this seems a far-fetched claim. In our sample, the share of German citizens deeply dissatisfied with democracy is about 20 per cent (see Online Appendix A4). This is a considerable figure, but it is still safe to assume that in the eyes of citizens, Germany is basically a functioning democracy. Empowering DCFs in such contexts might eventually decrease (rather than increase) citizens' satisfaction with democracy.

It might also be argued that more experience with DCFs may lead to different evaluations. Comparing the effects for participants who had at least heard about DCFs versus participants who had no experience yields no substantial differences, except that those who have had negative experiences reject empowered DCFs even more clearly (see Online Appendix B5). This bolsters our conclusion that the generic legitimacy gap of DCFs may not be closed so easily and that DCFs may only play a limited and circumscribed role in our democracies for the foreseeable future.

Future research on external perceptions of DCFs' legitimacy will need to do two things. On the one hand, it needs to take a comparative route: we need to know how different institutional and cultural contexts shape citizens' perceptions of DCFs' legitimacy. As mentioned earlier, it may well be the case that political systems with ‘deep-seated democratic pathologies’ (Kuyper and Wolkenstein Reference Kuyper and Wolkenstein2019) will produce stronger support for the ‘empowered’ uses of DCFs. On the other hand, future research also needs to contrast different DCF designs with different designs of representative and direct-democratic institutions (see, for example, Pow Reference Pow2021). Considering the findings of our conjoint experiment, ‘blended’ forms of democracy could emerge that ‘mix’ different institutional elements and take contingency and citizen heterogeneity seriously. Rather than ‘catching’ the deliberative wave, it seems that only some (disaffected) citizens are ‘surfing’ on it, whereas many others are quite comfortable with exclusively supporting roles.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000059

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this article can be found on Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GHHVFV

Acknowledgements

We thank Anja Rieker, Cristina Lafont, Hannah Werner, Jane Mansbridge, Sofie Marien, John Dryzek, Mark Warren, Michael Bechtel, Michael Neblo and Simon Niemeyer for their helpful comments. Moreover, we thank the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Standing Group on Democratic Innovations and participants of the 2021 ECPR General Conference. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers who provided valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (project number 432370948).

Competing Interests

None.