There are a number of processes which led to the possibility of using <o> as an old-fashioned spelling to represent /u/. I will begin by discussing examples which may be attributed to the following sound changes:

(1) /ɔ/ in final syllables was raised to /u/ before most consonants and consonant clusters in the course of the third century BC, e.g. Old Latin filios > filius ‘son’;

(2) /ɔ/ was raised to /u/ in a closed non-initial syllable during the second century BC, e.g. *eontis > euntis ‘going (gen. sg.)’;

(3) /ɔ/ > /u/ before /l/ followed by any vowel other than /i/ and /eː/ in non-initial syllables (Reference SenSen 2015: 15–28), e.g. *famelos > *famolos > famulus ‘servant’ (cf. familia ‘household’).

For various reasons, including the relatively late confusion of /ɔː/ and /u/ discussed directly below, and the difficulty of removing false positives from searches in the database, trying to establish the rate at which old-fashioned <o> for /u/ appears in the epigraphic spellings of the first four centuries AD is not practical. In his list of changes wrought by time, all of which seem to be seen as deep archaisms, Quintilian includes some examples of type (1):

quid o atque u permutata inuicem? ut “Hecoba” et “nutrix Culchidis” et “Pulixena” scriberentur, ac, ne in Graecis id tantum notetur, “dederont” et “probaueront”.

What about o and u taking each other’s place? So that we find written Hecoba for Hecuba and nutrix Culchidis for Colchidis, and Pulixena for Polyxena, and, so as not to only give examples from Greek words, dederont for dederunt and probaueront for probauerunt.

Apart from after /u/, /w/ and /kw/, where the raising of /ɔ/ was retarded until the first century BC, which is discussed below (Chapter 8), there are few cases of <o> for <u> arising from these contexts in the corpora. Even where we do find <o>, a confounding factor in identifying old-fashioned spelling of /u/ of these types is the lowering of /u/ to [o] which eventually led in most Romance varieties to the merger of /u/ and /ɔː/. According to Reference AdamsAdams (2013: 63–70), this can be dated to between the third and fifth centuries AD, and did not take place at all in Africa.Footnote 1 This requires him to identify a number of forms which show <o> for /u/ as containing old-fashioned spelling (or having other explanations) in the Claudius Tiberianus letters (Reference AdamsAdams 1977: 9–11, 52–3; Reference Adams2013: 63–4).

He sees posso (P. Mich. VIII 469/CEL 144) not as a rendering of possum, but a morphological regularisation with the normal first singular present ending which shows up elsewhere; this is quite plausible. Also plausible, given the spelling with final <n>, is the influence of the preverb con- on the preposition cum, which is spelt con in 468/142 (8 times) and 471/146 (twice), but old-fashioned spelling could also be a factor.

The origin of the adverb minus ‘less’, is extremely uncertain. It could go back to *min-u-s, since /u/ is also found in the stem of the related verb minuō ‘I lessen’; this may also be the origin of the neuter of the comparative minor ‘smaller, lesser’ (Reference LeumannLeumann 1977: 543; Reference SihlerSihler 1995: 360). If this is correct, the <o> in the final of quominos (470/145) would not be old-fashioned. But alternative explanations would see adverbial minus and the neuter of the comparative both coming from *minos > minus (although this would have to be somehow secondary, since the usual comparative suffix is *-i̯os-; Reference MeiserMeiser 1998: 154; Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 384). If minus does come from *minus rather than *minos, quominos could be a false archaism, by influence from comparative minus, since the neuter of comparative adjectives normally did come from *-i̯os-.

However, sopera (471/146) for supra certainly never had *o in the first syllable. Reference AdamsAdams (1977: 10–11) originally saw <o> here as due to the merger of /u/ and /ɔː/, but subsequently (Reference AdamsAdams 2013: 64) suggests that the scribe may have seen <o> as also being old-fashioned, bolstered by the possibility that the lack of syncope is also an old-fashioned feature (supera is found in Livius Andronicus, in Cicero’s Aratea and in Lucretius; Adams loc. cit. and OLD s.v. supra).Footnote 2 It is of course not impossible that the scribe was hypercorrect here, but in the absence of other evidence for this false etymology this explanation is not particularly appealing.

In my view, it is more likely that sopera, and perhaps quominos, suggests that either the author, Claudius Terentianus, or the scribe, was an early adopter of lowered [o] for /u/ (and note that both cases of <o> are in paradigmatically isolated formations which may have made it difficult for the scribe to identify which vowel was involved).Footnote 3 It is also possible that one or both were not native speakers of Latin, which may also have led to problems in identifying the vowel for the scribe.

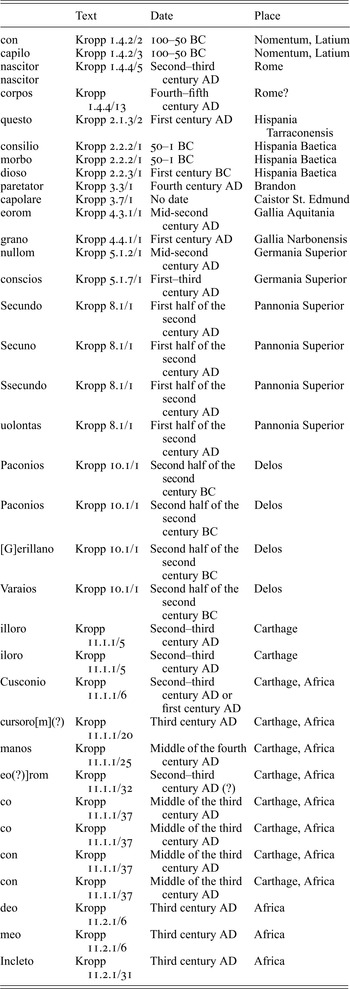

There are quite a number of cases of <o> for /u/ in the curse tablets (see Table 2), but I am doubtful of how many really reflect archaisms. con (Kropp 1.4.2/2), con (twice), co (twice, 11.1.1/37) for cum can be explained in the same way as in the Tiberianus letters, while second declension nominative singular masculine forms in -o(s) may be due to influence from other languages: Celtic in the case of Secundo, Secuno, Ssecundo (8.1/1, Pannonia, first half of the second century AD), if it really represents Secundus.Footnote 4 This tablet also has uolontas for uoluntās, but it uses <u> for /o/ in lucuiat (apparently for loquiat or loquiant, an active equivalent of loquātur or loquantur), as well as a number of spellings which cannot be explained as due to normal features of spoken Latin (<i> for /ɛ/ in ageri for agere and limbna for lingua), so we cannot be sure uolontas does not arise from the writer’s problems with spelling or abnormal phonology.

Table 2 <o> for /u/ in the curse tablets

| Text | Date | Place | |

|---|---|---|---|

| con | Kropp 1.4.2/2 | 100–50 BC | Nomentum, Latium |

| capilo | Kropp 1.4.2/3 | 100–50 BC | Nomentum, Latium |

| Kropp 1.4.4/5 | Second–third century AD | Rome |

| corpos | Kropp 1.4.4/13 | Fourth–fifth century AD | Rome? |

| questo | Kropp 2.1.3/2 | First century AD | Hispania Tarraconensis |

| consilio | Kropp 2.2.2/1 | 50–1 BC | Hispania Baetica |

| morbo | Kropp 2.2.2/1 | 50–1 BC | Hispania Baetica |

| dioso | Kropp 2.2.3/1 | First century BC | Hispania Baetica |

| paretator | Kropp 3.3/1 | Fourth century AD | Brandon |

| capolare | Kropp 3.7/1 | No date | Caistor St. Edmund |

| eorom | Kropp 4.3.1/1 | Mid-second century AD | Gallia Aquitania |

| grano | Kropp 4.4.1/1 | First century AD | Gallia Narbonensis |

| nullom | Kropp 5.1.2/1 | Mid-second century AD | Germania Superior |

| conscios | Kropp 5.1.7/1 | First–third century AD | Germania Superior |

| Secundo | Kropp 8.1/1 | First half of the second century AD | Pannonia Superior |

| Secuno | Kropp 8.1/1 | First half of the second century AD | Pannonia Superior |

| Ssecundo | Kropp 8.1/1 | First half of the second century AD | Pannonia Superior |

| uolontas | Kropp 8.1/1 | First half of the second century AD | Pannonia Superior |

| Paconios | Kropp 10.1/1 | Second half of the second century BC | Delos |

| Paconios | Kropp 10.1/1 | Second half of the second century BC | Delos |

| [G]erillano | Kropp 10.1/1 | Second half of the second century BC | Delos |

| Varaios | Kropp 10.1/1 | Second half of the second century BC | Delos |

| illoro | Kropp 11.1.1/5 | Second–third century AD | Carthage |

| iloro | Kropp 11.1.1/5 | Second–third century AD | Carthage |

| Cusconio | Kropp 11.1.1/6 | Second–third century AD or first century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| cursoro[m](?) | Kropp 11.1.1/20 | Third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| manos | Kropp 11.1.1/25 | Middle of the fourth century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| eo(?)]rom | Kropp 11.1.1/32 | Second–third century AD (?) | Carthage, Africa |

| co | Kropp 11.1.1/37 | Middle of the third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| co | Kropp 11.1.1/37 | Middle of the third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| con | Kropp 11.1.1/37 | Middle of the third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| con | Kropp 11.1.1/37 | Middle of the third century AD | Carthage, Africa |

| deo | Kropp 11.2.1/6 | Third century AD | Africa |

| meo | Kropp 11.2.1/6 | Third century AD | Africa |

| Incleto | Kropp 11.2.1/31 | Third century AD | Africa |

The fairly late date of cor]pos (1.4.4/13) for corpus and paretator (3.3/1) for parentātur allow them to be attributed to lowering of /u/; both also contain other substandard spellings. Undated capolare and capeolare (3.7/1) for capitulāre could also be due to lowering (in an inscription whose spelling is anyway highly deviant). And nascitor for nascitur (twice, 1.4.4/5), dated to the second or third centuries AD, could also be a precocious example of this; so could conscios (5.1.7/1) for conscius if it belongs towards the end of its date range. Both contain other substandard spellings. Having accepted that [o] for /u/ might be attested in the Claudius Tiberianus letters, I would suggest that this may also be a possibility for eorom (4.3.1/1) for eōrum, and nullom (5.1.2/1) for nūllum, also from the second century AD. The preponderance of cases in the final syllable might point to lowering occurring there first, in parallel to the situation of /i/ to [e].

Given their datings to the first century BC and first century AD, capilo (1.4.2.3) for capillum, questo (2.1.3/2) for quaestum, cos[i]lio, morbo (2.2.2/1) for cōnsilium, morbus, dioso (2.2.3/1) for deorsum, granom (4.4.1/1) for grānum could be old-fashioned spellings. Some of these texts also contain substandard spellings. None of them is in a context in which a mistake of ablative for nominative or accusative is very easy to envisage.

If Adams is right that the lowering of /u/ to /o/ did not take place in Africa (but see footnotes 1 and 10), old-fashioned spelling becomes a plausible explanation for a few instances there of <o> for /u/ from the second to third centuries AD. Incleto for Inclitum (11.2.1/31) I attribute to influence from the Greek second declension ending -ον, since the text has other examples of interference from Greek spelling.Footnote 5 11.1.1/32 has eo(?)]rom for eōrum, but in addition to substandard spellings has a number of mechanical errors. So does 11.2.1/6, and there is also the possibility that p]er deo meo reflects an error in what case goes with per rather than an old-fashioned spelling of deum meum. The other example of a noun following per in this text is Bonosa for Bonōsam, so the author may have thought that per took the ablative. But we do find illoro, iloro for illōrum (11.1.1/5), Cusconio for Cuscōnium (11.1.1/6), cursoro[m] for cursōrum (11.1.1/20). There is no reason to imagine that Cusconio is an ablative since it forms part of a list of four names in the accusative. Many of these texts also contain substandard spellings.Footnote 6

Overall, it is striking how many cases of <o> for /u/ there are in the curse tablets. I am reluctant to see them all as old-fashioned features, especially since few of the texts show any other such spellings; in practically all of the texts there are several other endings in -us or -um, and there seems no reason why a single word should be marked out in this way, especially in cases like the three names in sequence Cosconio Ianuarium et Rufum (11.1.1/6). I have more sympathy than Adams does with the idea that we may be seeing early signs of the lowering of /u/ to [o] that is better evidenced in much later texts; one could even suppose that in African Latin /u/ did lower to [o] in final syllables as elsewhere, but since /ɔː/ did not merge with /u/, [o] simply remained an allophone of /u/. One should also note that the intrinsic difficulties in the writing and reading of (often very damaged) curse tablets do make them more unreliable than other types of epigraphic evidence (Reference KroppKropp 2008a: 8).Footnote 7 On the other hand, all the examples of <o> for /u/ from the curse tablets do come from original /ɔ/, unlike with sopera and perhaps quominus in the Claudius Tiberianus letters, and a few of them are very early compared to the emergence of good evidence for the merger of /ɔː/ and /u/. So I do not rule out the possibility that some of these <o> spellings are old-fashioned.

There is one Augustan example of <o> for /u/ < /ɔ/ in the letters, in the form of Dìdom (CEL 8, 24–21 BC), which appears to represent the name Didium. It seems strange that an old-fashioned spelling should be used here but not in the name [I]ucundum with which it is conjoined (or indeed in the other accusative singular second declension form in this letter, decrìminatum), but no other explanation arises.Footnote 8 Another damaged letter (CEL 166, around AD 150) has epistolám, which is reasonably likely to be an old-fashioned spelling (assuming this is not an early example of lowering of /u/).

There are two possible examples in the Bu Njem ostraca, but kamellarios (O. BuNjem 76) is very uncertain: it could be a nominative singular for accusative, which is common in the ostraca (Reference AdamsAdams 1994: 96–102), but could also be an accusative plural (this is how Adams understands it). The other is ]isṭolạ[ (114), which may reflect epistola for epistula; but apart from the fact that the reading is not certain, there is a certain amount of evidence for confusion between /ɔː/ and /u/ at Bu Njem (see fn. 10).

Another case of <o> for <u> occurs in cui, the dative singular of the relative pronoun quī and the indefinite pronoun quis. An older form is quoiei (CIL 12. 11, 583, 585) and it had come to be spelt quoi around the start of the first century AD, according to Quintilian:

illud nunc melius, quod “cui” tribus, quas praeposui, litteris enotamus, in quo pueris nobis ad pinguem sane sonum qu et oi utebantur, tantum ut ab illo “qui” distingueretur.

We now do better to spell cui with three letters, as I have given it here. When I was a boy, they used qu and oi, reflecting its fuller sound, just for the purpose of distinguishing it from qui.

The passages of Velius Longus (13.7 = GL 8.4.1–3) and Marius Victorinus (4.31–32 = GL 6.13.11–12) quoted on pp. 166–7 suggest that the spelling quoi, and its genitive equivalent quoius, was also old-fashioned for these writers. We find no examples of quoi in the corpora, but the strange spelling cuoì, [c]ụ[o]i (TPSulp. 48) in the parts of a tablet written by the scribe presumably reflects a sort of compromise between quoi and cui (the non-scribal writer spells the word cuì). I know of no other examples of this spelling in Latin epigraphy.

Another conceivable instance of an old-fashioned spelling involving <o> are fornus (O. BuNjem 7), for[num (49), fornarius (8, 25), foṛ[narius] (10) for furnus, furnārius. The sequence /ur/ < *or or *r̥ in the standard forms of these words is unexpected; a dialectal sound change or borrowing from other languages is often supposed (I have argued for the latter: Reference ZairZair 2017). So these words could represent the original, older form, which is attested in manuscripts of Varro and by writers on language (Reference ZairZair 2017: 259). However, influence from fornāx ‘furnace, oven’ is also possible (thus Reference AdamsAdams 1994: 104);Footnote 9 another possibility is that /u/ was lowered by the following /r/ in syllable coda, which by this time was ‘dark’ in Latin (Reference Sen and ZairSen and Zair 2022). This might be particularly likely if there was some confusion of /ɔː/ and /u/ at Bu Njem.Footnote 10