Michael Smith and Frances Berdan (2003), in a recent discussion of Late Postclassic Mesoamerica, employ an innovative version of world-systems theory in an attempt to understand the widest sociocultural interactions operating within that civilization. Like most early proponents of world-systems (e.g. Wallerstein 1974a, 1974b; Frank and Gills 1993) Smith and Berdan put primary emphasis on economic factors, especially commercial activities, to explain the emergence and development of this powerful aboriginal interaction sphere. Nevertheless, in accordance with arguments by later revisionist world-systems scholars (e.g. Chase-Dunn 1992; Chase-Dunn and Hall 1997; Peregrine and Feinman 1996), these authors also take into account political, military, and “informational” factors. In addition, Smith and Berdan place much less stress on core/periphery relations than did the early world-systems scholars, arguing for a complex set of interacting units that include core zones, affluent production zones, resource-extraction zones, exchange circuits, style zones, and international trade centers. Their scheme expands on the concept of world-systems cores, suggesting that core units constitute the top of a hierarchy of diverse sociocultural units (e.g. “affluent production zones,” etc.). In Wallerstein's (1991, 1979) world-systems scheme most of the units listed by Smith and Berdan functioned as “semi-peripheries” mediating between cores and peripheries.

Of particular interest is the diminished structural role assigned to the so-called peripheries, which Smith and Berdan refer to as unspecialized peripheral zones (remote isolated areas, as in the northern part of Mexico) and contact peripheries (“areas that had only slight contact with a world system,” such as the Greater Southwest and Lower Central America). The standard world-systems thesis of economic and political domination of peripheries by cores is replaced by reference to sporadic and transitory relations between so-called peripheries and the core or the other zones mentioned above. Smith and Berdan emphasize that cores did not necessarily dominate peripheries in the Mesoamerican world-system. Furthermore, they specifically argue that Northern Mexico up to Casas Grandes, and Central America below the Maya zone, were “extra-systemic”; they are to say, it is outside the Mesoamerican world-system. We see both Northern Mexico up to Casas Grandes, as well as Central America as far south as Pacific Nicaragua and Nicoya, as peripheries of Mesoamerica (cf. Lange 1986). In turn, the areas that extend beyond these peripheries to the north of Mesoamerica, in what is now the Southwest United States, and to the south in Costa Rica, Panama, and part of northwestern South America are best considered to be extra-systemic, or as we refer to them, “frontier” zones.

We challenge, then, the argument that Lower Central America as a whole falls outside the Mesoamerican world-system. We attempt to show that native peoples along the Pacific Coast of Central America from El Salvador to the Nicoya Peninsula should be understood as forming part of a prehispanic Mesoamerican periphery, while the peoples on the Atlantic side and south of Nicoya form part of a Mesoamerican frontier. Frontier peoples, as we define them here, are “frontier” only relative to core or peripheral peoples of some other world-system; that is to say, they lack “systematic” relations with that world-system, and as a result their social and cultural formations are not fundamentally maintained through such relationships. Frontier zones should have no negative connotations, for they are occupied by peoples with their own culturally relevant institutions, cultural features, and interaction spheres. Thus, if the subject of study were to be on the interaction spheres of the Chibchan chiefdoms of lower Central America, it would be entirely consistent to refer to their northern Mesoamerican neighbors in Nicoya and Nicaragua as frontier peoples.

The native peoples located in the proposed Lower Central American frontier can be seen as having their own world-systems, made up of interacting chiefly polities (Carmack 1993). Nevertheless, relative to the Mesoamerican world-system, they constituted a known frontier zone. The mostly Chibchan-speaking peoples there engaged in intermittent trade and preciosity exchanges (in gold among other items) with Mesoamerican peoples located in the so-called Greater Nicoya area (Pacific coastal Nicaragua and the Nicoya Peninsula) (Vázquez 1994), but their sociocultural institutions and interaction spheres were not determined by such exchanges.

Although the world-systems perspective provides a broad framework for this essay, we are not primarily interested in testing the validity of world-systems theory. Indeed, we consider world-systems “theory” to be a heuristic model rather than a theory per se. From a more empirical perspective, we want to examine archaeological and ethnohistoric evidence as it bears on the relations between the peoples of Lower Central America and Late Postclassic Mesoamerica. Regrettably, space does not permit us to summarize the archaeological and ethnohistoric evidence available on either the broader Mesoamerican periphery in Nicaragua and Nicoya nor the evidence on the Chibchan frontier in Costa Rica and Panama. Instead, we confine our study to documentary and artifact information from two “microhistorical” cases of peoples located on both sides of the Mesoamerican/Lower Central American border: the Chorotegans of the Masaya/Granada area in Nicaragua, and the Chibchans of the Buenos Aires/Diquis area in Costa Rica. For these archaeological and ethnohistoric accounts we draw heavily on our own investigations of these two specific areas of Central America (Salgado 1996, 1997, 2001; Salgado and Zambrana 1994; Salgado et al. 1998; Carmack 1991, 1993, 1994, 1998, 2002), as well as on the research of others (see the citations below).

MICROHISTORY OF THE GRANADA/MASAYA AREA OF PACIFIC NICARAGUA

Archaeological Account

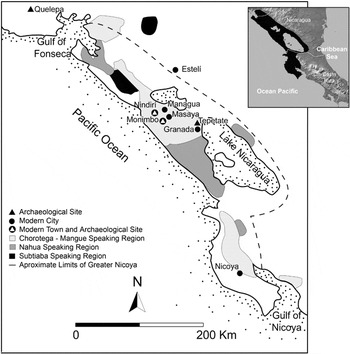

In the past decade regional surveys have covered a continuous area of about 500 km2 (Salgado 1996; Salgado and Zambrana 1994; Salgado et al. 1998; Braswell et al. 2002) in the provinces of Granada and Masaya of Pacific Nicaragua (for the locations of these provinces and sites mentioned in this section, see Figure 1). The area falls within what has been called Greater Nicoya, encompassing Pacific Nicaragua and NW Costa Rica, considered initially as a subarea of Mesoamerica (Norweb 1964; Willey 1966).

Map of Mesoamerica's southern periphery with sites mentioned in the text.

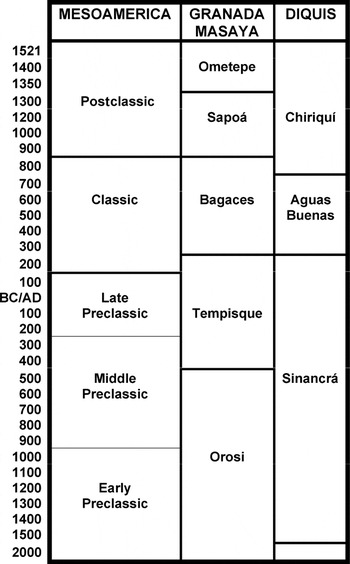

The peoples of the area interacted with peoples of Mesoamerica from the Formative on, even though the nature, intensity, and direction of this interaction changed through time (for chronologies to all areas discussed in this article see Figure 2). The earliest pottery emerged in the second millennium before Christ, and it shows similarities with the Barra ceramics (1550–1400 b.c.) in coastal Chiapas (Snarskis 1981; Hoopes 1994), indicating at least a general level of interaction between the two areas. During the Tempisque period, Usulutan pottery from the highlands of El Salvador and Guatemala was imported to sites of Granada by members of an emerging social elite, but pottery was also manufactured in neighboring areas of northern Nicaragua (Lange et al. 2003).

Chronological chart of areas discussed.

Social complexity consolidated during the Bagaces period when the regional elites apparently controlled a long-distance exchange network by which goods were obtained mainly from the Comayagua Valley in Honduras and the site of Quelepa in El Salvador, including pottery from both areas as well as prismatic blades manufactured from Ixtepeque's obsidian at the latter site. Whereas pottery and other artifacts from Lower Central American regions have been found at Quelepa. pottery from Copan and sites of western El Salvador is rare (Braswell et al. 1994:176,188). Quelepa probably was a colonial enclave established for economic purposes by newly arrived peoples from the Gulf Coast of Mexico (Andrews 1976; Braswell et al. 1994:188) that likely dominated a regional sector of an intersocietal network (world-system) that connected the Mesoamerican and Lower Central American regions (Sharer 1984; Joyce 1996; Braswell et al. 2002). The systemic nature of this network is shown by the decline of the main settlements in Granada/Masaya shortly after the decline of Copan, roughly at the same time as the decline of Quelepa.

At the onset of the early Sapoa period important changes took place. The sociopolitical organization was restructured with the emergence of new centers, and there was a significant transformation in all aspects of material culture, from settlement and funerary patterns to pottery and lithic industries.

In Granada there was an increase of 325% in the number of settlements, whereas in Masaya the increase was only 25%, which indicates that Granada was growing as the most important political and economic center of the area. Centuries later, the city of Granada was founded by the Spaniards, giving rise to one of the most important urban and administrative centers of colonial Nicaragua, a development that can be explained, at least in part, by the pre-Columbian changes just mentioned.

In the northern border of Granada lies the Tepetate site, very likely Xalteva, the principal prehispanic town in the region, as reported by the Spaniards. The site extends over 2 km2, and constituted a regional center not only in the early Postclassic Sapoa period but also during the late Postclassic Ometepe period (a.d. 1350–1522). More than 10 stone-faced mounds, 1 to 2 m in height, were arranged around a central plaza (Willey and Norweb 1959; Salgado 1996), a layout that could well correspond with the galpón units discussed in the ethnohistory section below.

Four nucleated villages formed a second level of the regional hierarchy, two of them possibly corresponding with the communities of Nenderi and Monimbo mentioned in the colonial documents as being part of the so-called Masaya province. The site corresponding with Monimbo extends under the present city of Masaya, and therefore is likely related to the ancient towns of Masaya and Monimbo. A third level was composed of villages and hamlets, among them the first permanent villages on Granada's Lake Nicaragua coast. Most of these settlements were fishing villages, as suggested by references in early colonial tribute records (Werner 2000).

Ceramic complexes also show notable changes, with the monochromes revealing new surface treatments and forms whereas the polychromes are defined by new technological attributes: the use of white slip and the application of orange and red color for painted motifs, surfaces that are polished but not shiny (as was the case in the previous period), pastes that are coarser and well oxidized, and new forms that included pyriform and effigy vessels.

The polychrome vessels show a threefold increase from the previous period. Although there is some continuity in the ceramic iconography, a new set of motifs without precedence in the local tradition became dominant. This new iconography has been linked with that found on Early Postclassic pottery from the Mexican Highlands (Day 1984; McCafferty 2001), West Mexico, and Central Veracruz (Smith and Heath-Smith 1980), and the Maya area (Lothrop 1998 ; Healy 1980). Healy (1976) suggests that the latter could be attributed to contacts between Chorotegan and Mayan populations as the former peoples migrated south along the Pacific Coast of Guatemala.

Specialized ceramic female figurines and tripod vessels of Papagayo Polychrome (Figure 3) were produced at Tepetate (Salgado 1996; 1997), and were distributed over an ample area ranging from northwestern Costa Rica to Pacific Nicaragua and northward. In addition, the abundance of obsidian prismatic blades and debris at Tepetate points to local production of core-blades made mainly of Ixtepeque material (Braswell 1998). In general, changes in the lithic complexes have clear ties with Mesoamerican industries, 33% of all artifacts being manufactured from obsidian. A biface industry, however, mostly used local chert. The manufacture of the stemmed round-based biface might indicate interaction with the southern Maya area, where that artifact became common during the Late Classic (Lange et al.1992).

Examples of artifacts manufactured at the Tepetate site: (a) Papagayo Polychrome figurine; (b) Papagayo Polychrome: Cervantes Variety bowl; (c) Molds for, right, a Cervantes bowl support, and left, a figurine.

The new dynamic economy can be attributed to the intensification of interaction with adjacent Lower Central America to the south and southern Mesoamerica to the north, perhaps in association with trade in controlled markets, as described in the historical sources. There is abundant evidence of goods from Lower Central American areas flowing into Postclassic Mesoamerican sites in the Central Highlands of Mexico and the Maya region, such as tumbaga artifacts and ceramics from Pacific Nicaragua. It is likely that Granada/Masaya was a significant node in the integration of those exchange networks, and that it formed part of a Mesoamerican world-system periphery.

The changes discussed above probably can be attributed to the historically documented arrival of the Chorotegans in Pacific Nicaragua (Healy 1980; Salgado 1996, 2001; see below). The movement into Nicaragua by the Chorotegans and other Mesoamerican peoples may have been initiated by the disintegration and restructuring of the macroregional Mesoamerican world-system during the Late Classic and Early Postclassic periods (Fowler 1989:274). The knowledge that Mesoamericans had gained about the region through previous trade networks extending into Central America no doubt also played a key role in stimulating these later movements from the Mesoamerican heartland. According to Healy (1976), the Chorotegans likely followed the Pacific Coast trade route that connected Mexico with Central America, perhaps taking advantage of existing “ports of trade” (international trade centers) in order to avoid territories that might result in conflicts with peoples located along the pathway leading southward to Lower Central America.

Ethnohistorical Account

At the time of Spanish contact various Chorotegan provinces flourished in Nicaragua (for locations, again see Figure 1). The Spanish chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdez (1959:363) explained: “Nicaragua is a great kingdom of many and good provinces, and most of them are four or five leagues apart and diverse one from the other” (all translations in this section of Spanish texts to English are by R. Carmack). One of these provinces was no doubt Masaya, which according to the Spaniards numbered around 100,000 people residing in a series of communities that encircled a volcano and lake by the same name (“Masaya”). From colonial documents we learn the names of other Masaya provincial communities: viz., Diriega, Namborina, Niquinohomo, Nomotibia, Nandayme, Nenderi, Monimbo, and Masaya itself (these communities can still be identified today in the departments of Granada and Masaya). The so-called Masaya province no doubt was organized around political confederations between communities such as those just mentioned. The confederations apparently fragmented easily into smaller political alliances in conflict with one another.

Events associated with the arrival of the Spanish conquistador Gil González de Dávila in 1523 (Incer 1990) suggest that one of the “great chiefs” of the Masaya alliance at the time was Diriangen. The Chorotegan Diriangen and his followers were well informed about contacts the Spaniards had made with the Chorotegan's enemies to the south, the Nicaraos, and in a highly institutionalized and diplomatic encounter, Diriangen met with Gil González somewhere in or near the Masaya/Granada area. Diriangen was accompanied by 500 men, 10 standard bearers, and 17 women adorned with gold pectorals. To the sound of loud trumpets, they offered the Spaniards standard elite “gifts” of food, gold, and slaves: over 500 turkeys, more than 200 gold or copper ax-shaped sheets, and presumably the 17 female slaves.

Three days later Diriangen attacked the Spaniards with 4,000 warriors, armed with cotton vests, protective headgear, shields, swords (made of wood edged with obsidian blades), slings, and bows and arrows. The Masaya natives fought fiercely against the Spaniards, but in the end were driven back and retreated to their own territory. The Spaniards were so concerned over the military prowess of the Chorotegan warriors that they decided not to continue forward through the Masaya province, but instead returned south to Nicarao territory and there on to Nicoya from whence they had entered the area.

The Spanish sources indicate that the fundamental social units of the Masaya province were galpones, each made up of a town plaza in which the “lord” and his assistants ruled over the surrounding wards and rural districts. The galpones appear to have been similar to the city-states described by Smith (2003) in his discussion of Postclassic Mesoamerican polities. Many of the Chorotegan sociocultural features survived the Spanish military invasion of Nicaragua. For example, the Masaya province itself became a corregimiento (administrative district) in the Spanish colony. Monimbo continued on, now as a pueblo with its own chiefs, one of whom was named Botoy (the “Putoys” remain influential in Monimbo to this day), assisted by two other authorities referred to in the Spanish documents as Nacay and Mendoti (from the Chorotegan terms nakume, “governor,” and mankeme, “speaker”).

Some Chorotegan galpon communities were “congregated” by the Spaniards into larger towns, as was the case with Masaya, where past communities became separate wards (referred to as parcialidades by the Spaniards). Each parcialidad had its own chief and principals. Apparently two Chontal communities (probably made up of Misumalpan and/or Chibchan-speaking peoples) were integrated into the Masaya town, forming a quadrapartite ward structure the remnants of which still exist in the city of Masaya today (García Bresó 1992:60–61). There is evidence too that Chorotegan clans and lineages integrated into the native galpon structures continued to function in Masaya throughout the colonial period (Membreño Idiáquez 1993).

Documentary research continues on the aboriginal and colonial Masaya province, inspired in part by the fact that two of Nicaragua's historical heroes—Diriangen and Augusto Sandino—were of Chorotegan stock from Masaya. The limited information on the area already available seems sufficient to state with confidence that the aboriginal Chorotegans had participated in a highly dynamic and socially complex world. They had acquired broad knowledge of political developments in the region (such as the arrival of the Spaniards to the south of Masaya), and the ability to organize elaborate political exchanges and large-scale military actions. The encounter between Diriangen and Gil González brings to light several Mesoamerican features: centralized leadership; stratification between elite, commoners, and slaves; axe-shaped copper and gold preciosities; obsidian-blade swords; protective cotton vests and headgear; ceremonial banners and martial music; sophisticated diplomatic and military tactics.

Detailed information on how the Masaya and Granada Indians adapted to Spanish colonial rule would reveal further similarities with the ways other Mesoamerican peoples adapted to Spanish colonial rule, a topic beyond the scope of this essay.

MICROHISTORY OF THE LOWER CENTRAL AMERICA DIQUIS/BUENOS AIRES AREA

Archaeological Account

Recent genetic and linguistic studies have shown that the Rio Diquís (also known as the Rio Térraba) drainage area, most of which is located in the township of present-day Buenos Aires, Costa Rica (for the location of places mentioned in this and the following section, see Figure 4), was inhabited by Chibchan-speaking populations that developed locally over a period of some 6,000 years (Constenla 1991; Barrantes 1993). Nevertheless, some authors have suggested movements of populations into the area from neighboring regions of Panama inhabited also by Chibchan speakers (e.g. Fonseca y Chávez 2003).

Map of the Diquis/Buenos Aires region with sites and resources mentioned in the text.

Archaeologists consider the Diquis to be part of a larger region known as Greater Chiriqui that extended from the continental divide of the Talamanca Cordillera to the coast of southeastern Costa Rica and western Panama. The reconstruction of developments in the area to follow draws mainly on the archaeological research of Robert Drolet (1984, 1988, 1992) and Francisco Corrales (1983, 1985, 2000).

The area has a long history of human occupation dating back to the Archaic period. By the Sinancra phase native agricultural and pottery-making groups occupied numerous hamlets in basins and river valleys without evidence of social and political ranking (Corrales 1985, 2000).

In the following Aguas Buenas phase, highland zones became the preferred location for settlements whose inhabitants depended on a mixed economy, based on agriculture and the exploitation of wild resources. The settlement pattern is characterized by distinct territories with extensions ranging from 4 to 7 km. Two of the territories had larger centers of about 5 ha, surrounded by dispersed hamlets of 1 ha each, indicating the presence of incipient regional hierarchies. In the larger centers are found restricted areas with refuse deposits and residential and burial mounds. Products such as stone pendants and ceramics were exchanged and/or traded among the territorial units of the Diquis and beyond, but there is no specific evidence of extensive long-distance trade. The only exception to this are a few polychrome vessels from Guanacaste found at Caño Island, located 17 km NW off the Osa Peninsula (Finch and Honetschlager 1986), which probably were obtained along maritime trade routes.

The final phase of pre-Columbian occupation, the Chiriqui phase, was characterized by increasing sociopolitical complexity. A two-tier settlement hierarchy is defined by nucleated villages on the lower level and large centers on the upper level. Nucleated villages of varying size and complexity proliferated along the banks of the Térraba (Diquís) river, indicating an intensification of agriculture in the fertile alluvial soils. The villages were divided into different residential units—ranging in extension from 3.5 to 13 ha—formed by circular houses similar to those found today among the Chibchan peoples of Talamanca, Costa Rica.

Each household manufactured most of the tools used in the daily routines of food preparation, wood working, and agriculture. Villages had access to extensive lands for agriculture, as well as to surrounding cemeteries that corresponded with specific social groups of the communities. Cemeteries reflected differences in wealth and status, with respect to both the size and the structure of the funerary mounds and other ceremonial structures, but also the differential layout and contents of the tombs.

Multi-village networks formed in which some villages specialized in the production of such crafts as polychrome pottery, cotton textiles, metallurgy, sculpture, shell and bone ornaments, and certain household tools. This specialization triggered exchange and/or trade, and social alliances must have served as important integrative mechanisms for the component chiefdoms.

A handful of large centers emerged in both the General Valley and the Diquís Delta, centers that were the seats of chiefly elites. Within them are found large stone-walled circular mounds, plazas, and paved roads.

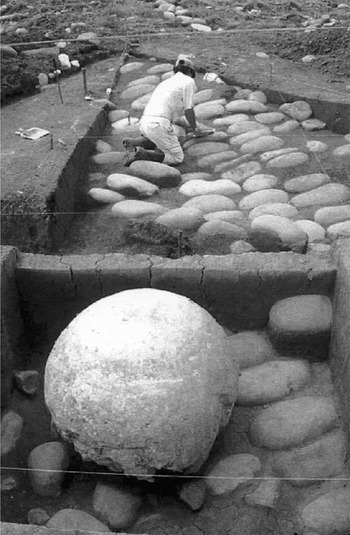

One of the largest centers known so far, is the site of Java, which has a large and nucleated area of over 44 ha, and although many architectural features have been obliterated, the archaeologists located and mapped 15 mounds originally circular in form, 11 of which were grouped around a central plaza. As in the case of other large regional centers of the period, spheres (Figure 5), barriles, and anthropomorphic peg-based statues (Figure 6a–c) were placed within and around the mounds. It has been argued that Java was the probable fortress of Coto (Fonseca y Chávez 2003), the historically documented chiefdom described below that dominated the territory of the Diquis area. The site is located on a hill near the “Mule Route” (Camino de Mulas), an important colonial trade route that probably functioned in the pre-Columbian period as well.

Wall of mound's base and sphere in situ at the Palmer site. Photograph courtesy of Adrían Badilla, National Museum of Costa Rica.

(a–c) Statues typical of the Chriqui Phase. Photographs courtesy of the National Museum of Costa Rica; (d) Gold pendant of the Diquis/Buenos Aires region.

Another impressive site in the Diquis area is Palmar, located near placer sources in the alluvial lands of the southern delta. Its extension has not yet been clearly determined, but it was much larger than any other known site in the area. It has an abundant display of monumental architecture and large stone spheres, peg-based zoomorphic and anthropomorphic statues, impressive amounts of metal funerary offerings (Figure 6d), and evidence of their manufacture at the site (Badilla, Quintanilla, and Fernández 1997; Fernández and Quintanilla 2003). Reportedly, a single tomb contained close to 100 gold ornaments associated with a single individual, most of the ornaments being locally made; some, however, may have been imported from Panama or even northwestern Colombia (Badilla, Quintanilla, and Fernández 1997).

Macroregional interaction in the Chiriqui region is shown by the emergence of regional styles in metallurgy that exhibit what might be considered as a “horizon” style stretching from northwestern Colombia to Costa Rica (Bray 1984). Gold was obtained from local placer deposits of the riverine system of the Diquis Delta, but the copper needed to create the alloy known as tumbaga is found to the north, in the Central region of Costa Rica; it was probably obtained through trade.

Polycrome pottery from Nicaragua, Guanacaste, and central Panama has been found at Palmar and to a lesser extent at the Rivas site located eastward in the General Valley (Quilter 2004) and at Caño Island. It is likely that some gold artifacts found in Guanacaste and Nicaragua moved further north through exchange networks from the Diquis area. As already mentioned, gold ornaments appearing in Postclassic Maya sites were probably brought there by Mesoamerican traders from Nicaragua and Guanacaste, who in turn had obtained them from the South Pacific areas of Costa Rica and Panama (Ibarra 2003).

Around a.d.1400 some large villages and ceremonial centers were abandoned and a process of political fragmentation took place in the Diquis (Quilter 2004). When the Spaniards first entered the region, perhaps the chiefdoms they encountered were smaller and less powerful than those that had flourished there in prior centuries.

Ethnohistorical Account

In a previous publication (Carmack 1993) the argument is made that south of Nicoya the Chibchan peoples of Costa Rica and Panama in late prehispanic times were linked together into an independent “chiefly world system,” which also constituted a frontier with respect to the Mesoamerican world-system (see also Ibarra Rojas 1990; 2001).

The Spanish invasion of the southeast area of Costa Rica that later became the township of Buenos Aires was initiated in 1563 by the conquistador Juan Vázquez de Coronado (Fernández Guardia 1908). Vázquez first made contact with the Pacific coastal chiefdom of Quepo, which then became the launching point for incursions further south and into the interior. The Spaniards soon came upon a large valley that Vázquez described as a savannah heavily populated with Indians. This was probably a reference to the Valle del General, within which the center of the Buenos Aires township is now located (Carmack 1994).

One of the most powerful chiefdoms of the valley was Cia, thought to be located at the site of the present-day Buenos Aires town center (Chacón 1986; Lieberhaber 1964). Given the geography of the site, the Cia chiefdom must have controlled a large territory of flatlands, rich in fish and game. According to Spanish accounts, the Cia political center was spacious and well fortified, surrounded by a double stockade, and inhabited by over 1,000 persons residing inside its fences. The basic social units of the chiefdom appear to have been matrilineal clans, presided over by a chief who in 1569 bore the (clan?) name of Quizicará.

As the conquistadors marched further south from the Valle del General, they encountered hostile native polities. The Boruca and Coto chiefdoms were among the approximately 13 settlements identified by the Spaniards as having well-defended political centers (palenques). Like the Quepo and Cia polities, the Borucas and Cotos spoke the “Boruca” (Brunka) Chibchan language. The Spaniards met particularly violent resistance from the Coto chiefdom (sometimes spelled in the documents as Couto or Coctu), its political center located on an elevated, narrow slice of land surrounded by rivers.

Vázquez de Coronado (Fernández Guardia 1908:32ff) described the Coto polity in considerable detail through letters sent to Spanish officials, and his accounts provide us with our best documentary information on the prehispanic chiefdoms of the Diquis area. One of the most notable features of these chiefdoms as described by Vázquez is that they were embroiled in continuous political and military conflicts. For example, while the Spaniards were in Quepo they learned that the Cotos had attacked the Quepo chiefdom, carried off the chief's daughter, and enslaved other captives. The Coto center itself was heavily fortified, surrounded by two stockade-type fences with pits dug between them, while its two small entryways were protected by three fences, pits, and small bridges.

When the Spaniards tried to enter the Coto center, they found rows of raised conical houses from which the Cotos launched lances, arrows, and stones at them. The Spaniards claimed that there were more than l,600 Coto fighting men residing in the center (divided between two forts), and that they were also materially aided by certain “amazon” women. The Coto warriors were not only well armed (with lances and clubs) but also were protected by tapir-skin shields and cotton vests. Brush fires were employed by the Cotos as an additional weapon to fend off the Spaniards. Vázquez (Fernández Guardia 1908:32) evaluated the Cotos' overall militarism in the following words: “The Indians are extremely warlike, bellicose, and they are always armed because of the wars they have with surrounding peoples…. [They] have destroyed more than forty towns in the region.”

Not surprisingly, the Spaniards were particularly interested in the military capabilities of the Coto people. Vázquez also praised them for being “a lucid people with well developed [but scarred] arms and bodies, Indians of good judgment who tell the truth” (Fernández Guardia 1908.34). He found them to be “very” rich in gold, cotton, maize and beans, fruits, peccary and deer meat, as well as riverine fish. They manufactured fine ceramics and delicate cotton clothing. Vázquez was turned off, however, by a small ritual zone lying just outside the fort, where the Cotos deposited “the heads and dead bodies of those who were captured in war and were sacrificed [beheaded], except for the women and children who were kept as slaves until [their captors] die and they are buried with them” (Fernández Guardia 1908.35). Nevertheless, the Spaniards were told that the Cotos did not eat human flesh.

The main Coto chief resided in the center of the fort, along with other lesser chiefs and authorities, who apparently were heads of clans. Vázquez claimed that some 25 families, probably members of the same clan, resided in each of the numerous “round houses with conical roofs.” The chiefly leaders appeared to have monopolized the possession of gold objects, and apparently held rights to placer rivers within the chiefdom's territory, where gold was panned. One Coto chief offered a “royal eagle” made of fine gold to the Spaniards. Vázquez, obviously preoccupied with warfare, claimed that most of the common men were so strongly militarized that “they only understand warfare” (Fernández Guardia 1908: 34). In contrast, the women, besides helping the Coto men in battle, tended the milpas and wove fine cloth. As noted, slaves captured in warfare formed the bottom segment of Coto society. They were subject to their captors but in the end became sacrificial victims.

All attempts by the Spaniards during the early years of the invasion to establish towns in the Buenos Aires area failed, including an early Spanish town named Nombre de Jesús. Apparently without exception, the inhabitants of the chiefdoms in the area abandoned their aboriginal centers and fled to the mountains. Coto disappeared as an identifiable community, and not until the seventeenth century were the Spaniards finally able to establish two Indian towns in the area: Boruca, and Térraba (the latter populated by Indians speaking a different Chibchan language brought to the Buenos Aires area from Panama). The key economic factor that made possible the establishment of the colonial Boruca and Térraba communities was the (forced) service the Indians provided to mule teams passing through the area on the way to Panama. As late as 1680, when a Spanish official was sent to determine the condition of the Indians in the General Valley, he found only “some 500 families, very bellicose and dispersed” (Chacón 1986:36).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Based on the archaeological and ethnohistoric data presented above, what can be concluded about the kinds of relationships that existed between Postclassic Mesoamerica and (1) the Chorotegans of Pacific Nicaragua, and (2) the Chibchans of Costa Rica? More generally, what can we conclude about the application of the world-systems perspective outlined at the beginning of this essay to these same relationships?

In the case of the Granada/Masaya area, the archaeological site of Tepetate provides crucial evidence for the integration of the area into the Mesoamerican world during the Postclassic period, an integration that could be well extended to the preceding period. The site reveals a standard Mesoamerican central plaza surrounded by masonry structures, a center that exercised political control over surrounding nucleated villages and scattered rural hamlets. The site's ties to Mesoamerica are further confirmed by its large number of polychrome ceramics and iconographic motifs originating in the Mesoamerican heartland. A more complete reconstruction of the prehispanic Chorotegan cultural world, it must be cautioned, will depend on much more intensive excavations of archaeological sites in the Pacific Nicaraguan area (see Braswell et al. 2002).

The ethnohistoric account of the encounter between the Spanish conquistador Gil González and the Chorotegan leader Diriangen in the Nicaraguan Pacific coastal area provides sociocultural details that support the argument that the peoples there were active participants in the Mesoamerican world. Diriangen's actions were consistent with the more cosmopolitan and standardized diplomatic protocol that characterized relations between the Mesoamerican city-states to the north. The 500 subalterns who accompanied him, along with standard bearers and trumpeters, and his use of well-established diplomatic procedures, all point to a political hierarchy typical of Mesoamerican city-state rulers. Similarly Mesoamerican were his large military forces, armed with obsidian-blade swords, cotton vests, and protective headgear. We note too that Diriangen offered the Spaniards one of Mesoamerica's most important currencies: sheets of gold and/or copper.

Some scholars have argued that the Chorotegas of Greater Nicoya fell outside the Mesoamerican interaction sphere. Nevertheless, in addition to the evidence revealed by the Granada/Masaya case, there is credible ethnohistoric information that supports our conclusion that the Chorotegas (and Nicaraos) were indeed authentic participants in the Mesoamerican world. In a summary of this additional evidence, Carmack (1996:109) concluded that “… the cultural ideas and practices of the Chorotega were clearly Mesoamerican, and they actively engaged other Mesoamerican units in trade, political alliance, and warfare.”

From a world-systems perspective the question arises as to whether or not the Chorotegan peoples of Pacific Nicaragua occupied a peripheral position in the Mesoamerican system. In the Smith and Berdan model, they might be classified as participants in a Mesoamerican “Unspecialized Peripheral zone,” and therefore more isolated than exploited. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that the relationship between the Chorotegas and the Mesoamerican core powers to the north was largely one of inequality. For example, according to an account published by the Spanish chronicler Torquemada (Esgueva Gómez 1996:29–31), the Chorotegans and Nicaraos from time to time were forced to pay tribute to Aztec forces (pochteca) in the early sixteenth century. Furthermore, it is likely that the Chorotegan peoples also traded on unequal terms in the long-distance markets mentioned in the documents, in which no doubt Aztec and Mayan merchants from the Mesoamerican core zones sold dearly and bought cheaply.

As for the aboriginal Chibchan peoples south of Pacific coastal Nicaragua and Nicoya (“Greater Nicoya”), the artifact and documentary evidence indicates that they had constructed their own chiefly interaction spheres, and thus formed largely autonomous sociocultural worlds relative to the Mesoamerican world to the north (see Hoopes and Fonseca [2003], for a thorough discussion of the Chibchan world as an independent sphere of “diffuse unity”). There is no solid evidence that Chibchan sociocultural institutions had been systematically transformed by influences coming from Mesoamerica. At least during the Postclassic period, a basic sociocultural border located along the eastern shoreline of the Nicoya Bay had been established between the Mesoamerican and lower Central American Chibchan peoples.

The evidence for this sociocultural divide is particularly clear in the case of the Chibchan peoples inhabiting the Diquis/Buenos Aires area. As discussed above, archaeological research points to a largely in situ development there, major external influences coming from Panama to the south rather than from the north. Furthermore, the microhistory of the Diquis peoples is consistent with prior studies that delineate the unique sociocultural features of the Chibchan chiefdoms and the kinds of exchange networks that bound them together in the region (Helms 1979; Ibarra 1990, 2003).

Some of the more general contrasting cultural features between the Chibchan and Mesoamerican peoples (contrasts that have sometimes been exaggerated by scholars) would include the following: ranked chiefdoms (Chibchan) in contrast with status-based city-states (Mesoamerican); matrilineal versus patrilineal descent; gold as an exchange object versus as market currency; prevalence of shamanic versus priestly ritual; absence of a written script versus an international writing style. Particularly telling were the differences in cosmologies between the Chibchan and Mesoamerican worlds, indicated in the Chibchan case by a distinct regional iconography represented on recovered artifacts, as well as in the highly distinct cosmological ideas that have been recorded from contemporary Chibchan peoples (for the Diquis area, see Bozzoli 1986).

There can be no simple answer as to whether or not the archaeological and ethnohistoric data fully support our claim that the Postclassic peoples of Pacific Nicaragua formed part of the Mesoamerican world-system periphery while the Chibchan peoples of Costa Rica and further south constituted an independent interaction sphere and therefore one of Mesoamerica's main frontiers. The fundamental assumption of the world-systems model is that the sociocultural institutions of participant peoples within large intersocietal networks are restructured as a result of interactions between the different sectors of the system. Most world-system advocates think that political domination and economic exploitation characterize all world-systems and that inevitably powerful core peoples exploited weaker peripheral peoples (a process usually mediated by social groups that have some power but also major liabilities vis-à-vis the core and peripheral sectors).

It is increasingly argued by scholars (e.g. Schortman and Urban 1994), however, that historically, intersocietal political and economic networks have developed in which exploitation and domination were minimal or even non-existent. In such cases, so-called core/periphery relations have taken the form of sociocultural differentiation rather than exploitation; or the relations have involved some degree of exploitation by both core and peripheral participants, perhaps by employing different modes of power (e.g. political, military, economic, ideological). At a minimum we should recognize that participation in a world-system is not an “all-or-nothing” process.

This last point is pertinent to both the Chorotega and Chibchan cases. We have argued that the Postclassic Chorotegas of Nicaragua and Nicoya were in a peripheral relationship with the Late Postclassic Mesoamerican world-system, and that this relationship may have involved significant inequality. Other scholars (e.g. Stone 1966), however, have argued against this positioning of the Chorotegas in the Mesoamerican world, pointing instead to their cultural similarities and close relations with the Chibchan and other peoples of Lower Central America. Indeed, these similarities—such as the exchange of gold pieces and the use of coca—were important, and a more in-depth study of the Chorotegas would have to take account of their position vis-à-vis the Chibchan world. If the Chorotegas were peripheral to Mesoamerica, they were also a frontier to the Chibchan world.

Similarly, Ibarra (2001:70ff) has shown that ties with the Mesoamerican world-system were having an impact on the Chibchan frontier, especially during the Late Postclassic period. The Chibchans traded with Mesoamericans through networks stretching along the Pacific Coast to Nicaragua, and there were exchanges as well with Mesoamerican enclaves located along the Atlantic Coast. The protective vests and headgear worn by Chibchan warriors in the Diquis/Buenos Aires area suggest some of the cultural information they might have received from the Mesoamerican peoples. The sociocultural formations of so-called frontier or extra-systemic peoples invariably are influenced to some degree by forces emanating from external world-systems. As McGuire (1995:60) comments in connection with a similar case of world-systems frontier relationships—between prehispanic Mesoamerica and the Southwest U.S.—that while they were not world-system in nature, neither were they merely “epiphenomena.”

RESUMEN

Los autores cuestionan el argumento a aquellos autores que sostienen que la Baja América Central no era parte del sistema mundo mesoamericano durante el Posclásico. Los datos arqueológicos y etnohistóricos aquí discutidos, sostienen el que los pueblos de la Baja América Central, situados desde El Salvador hasta la Península de Nicoya, eran parte de la periferia mesoamericana durante ese periodo. Se analizan dos casos “microhistóricos” de pueblos situados a ambos lados de la frontera de Mesoamérica y la Baja América Central, específicamente el de los Chorotega-Mangue que habitaron la zona de Masaya y Granada en Nicaragua y, el de los pueblos hablantes de lenguas de la estirpe Chichoide de la región de Diquis-Buenos Aires en el sur de Costa Rica. Los datos arqueológicos y etnohistóricos sugieren que los primeros eran activos participantes de la red interregional mesoamericana, mientras que los segundos sólo tenían débiles lazos con esta pero fuertes lazos con la red intersocietal de cacicazgos chibchoides.