1. Introduction

Across target languages, prepositions are described as difficult to learn (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman Reference Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman1999, Lorincz & Gordon Reference Lorincz and Gordon2012, Lam Reference Lam2018). But these difficulties are likely not specific to L2 users. Conventions of preposition usage are subject to group-based and individual variation and inconsistencies whether writers use their L1 or L2 (Brøndal Reference Brøndal1940, Ojanen Reference Ojanen and Viereck1985, Behrens & Mercer Reference Behrens and Mercer2007, Szymańska Reference Szymańska, Golden, Jarvis and Tenfjord2017). Therefore, even L1 users may be unsure about their usage patterns (Pedersen Reference Pedersen, Kunøe and Vive Larsen1995). Nevertheless, L2 research is traditionally based on the assumption that L1 users know their language perfectly, and so-called error rates are typically calculated as the rate of deviations from the language production of an idealized native speaker (Bokamba Reference Bokamba and Alatis1994), rather than the rate of deviations from the naturally occurring language of L1 users.

In this paper, we present a corpus study of written Danish that highlights the natural variation in preposition usage found in both L1 and L2 texts, thus downplaying the concept of the idealized L1 user. The study focuses on the use of the four prepositions for, i, på, and til (roughly corresponding to English for, in, on, and to, respectively). They are the most frequent prepositions in our corpus and among the 10 most frequent words in written Danish (Henrichsen & Allwood Reference Henrichsen and Allwood2005).

We assume that both the L1 group (Danish high school students) and the L2 group (adult students at a Danish language school) have non-standard usage of prepositions, but that they differ in profile. The profile of non-standard usage between groups may in part be due to differences in the manifestation of crosslinguistic influence from English. Other sources of non-standard usage for both L1 and L2 writers include influence from other known languages, language variation and ongoing language change, overgeneralization of structures, or simply typos. We carry out within-group and between-group comparisons to identify the profile of each group.

The standard for comparison in the article is the written norm as defined by the Danish Language Council, grammars, and dictionaries, by which both L1 and L2 texts are assessed in educational settings (with some modifications: see Section 3.1). When high school teachers and L2 teachers grade papers, part of their job is to distinguish between cases of acceptable linguistic variation (which ought not to affect the grade negatively) and cases of non-standard usage which do not adhere to officially regulated or perceived written language norms (and may therefore affect the grade). Employees at publicly funded schools in Denmark are by law obliged to follow the regulations of the Danish Language Council. If the grammars and dictionaries do not define the norm for preposition usage, the teachers must refer to their own intuitions on the norms of the majority of language users. Some teachers may thus be more willing to accept variants that are common in spoken Danish, e.g. due to ongoing language changes.

The semantics and distribution of prepositions in Danish as L1 and L2 has not previously been systematically studied and, in contrast to the other Scandinavian languages Norwegian and Swedish, there has been a lack of corpora of Danish L2 texts which would facilitate such studies. In this paper, we thus take the first steps towards identifying differences and similarities between L1 and L2 users when it comes to non-standard usage of prepositions in written Danish.

2. Background

2.1 The distribution and semantics of Danish and English prepositions

Prepositions are typically used to cover spatial and temporal domains. Crosslinguistically, there is wide variation in which meanings are distinguished and how different meanings are distributed among different prepositions. Even prepositions in closely related language do not match up. The Danish prepositions for, i, på, and til cover similar, although distinct, semantic domains when compared to the English prepositions for, in, on, and to, as shown in Figure 1. These distinctions exist despite similarity in form and etymology. Danish i and til are cognate to English in and to. Despite being both cognates and homographs, Danish for and English for rarely overlap in use. Danish på and til have a wider range of uses than English on and to.

Figure 1. Distributional overlap for English and Danish prepositions.

Note: Proto-scenes (according to Tyler & Evans Reference Tyler and Evans2003) for the English prepositions in, on, to, and for on the left. The middle part lists selected examples from Tyler & Evans (Reference Tyler and Evans2003). TR = trajectory, LM = landmark. The dotted lines covering the English examples and the Danish prepositions to the right illustrate how each underlined preposition in the English examples translates into Danish. The asterisk in one of the examples denotes that the English example could be translated by either Danish for (if the meaning is ‘on behalf of Carol’) or til (if Carol is the recipient).

In the following, we consider the semantic distribution of the four English prepositions and their Danish counterparts one by one. We discuss the proto-scenes of each preposition taking the cognitive analysis of English prepositions proposed by Tyler & Evans (Reference Tyler and Evans2003) as the point of departure. Under this analysis, proto-scenes are defined as abstract mental idealizations over experienced spatial scenes, which can be coded by prepositions. For instance, the figure shows that a Danish translation of the pear is in the bowl would use the Danish preposition i, whereas the preposition på would be used for the translation of the cow munched grass in the field.

As shown in Figure 1, the proto-scene for English in and Danish i both cover full (in a box) and partial containment (in the bowl) The Danish preposition på shares the contact meaning with English on, but covers a wider semantic field and overlaps distributionally with English in and to. In addition (not depicted in Figure 1), på overlaps with at in expressions like at the pharmacy ‘på apoteket’.

English to and Danish til differ in proto-scene. For English to, the proto-scene involves static orientation, while the Danish proto-scene involves motion of the TR towards the LM (one of the extended meanings of English to). For static orientation, Danish tends to use other prepositions such as på and mod.

English for and Danish for share core senses pertaining to motives, intentions, and meanings (Tyler & Evans Reference Tyler and Evans2003:153–154), but the domain covered by Danish for is much smaller. English for can be used in a ‘purpose sense’, ‘intended recipient sense’, and ‘benefactive sense’. In Danish, the benefactive sense can also be realized with for, but the purpose sense and the intended recipient sense are typically realized with til.

2.2 Crosslinguistic influence in L1 and L2 writers of Danish

When L2 users express themselves in an L2, material or structures from their L1 may be retained. This phenomenon has been called interference (Weinreich Reference Weinreich1953), negative transfer (Selinker Reference Selinker1992, Ellis Reference Ellis1994, Jarvis & Odlin Reference Jarvis and Odlin2000), and crosslinguistic influence (Sharwood Smith & Kellerman Reference Sharwood Smith and Kellerman1986, Jarvis & Pavlenko Reference Jarvis and Pavlenko2008). Previous studies of crosslinguistic influence in the written production of prepositions have primarily been concerned with the use of prepositions in English L2 texts and how the use of English prepositions is influenced by the L1 of the writers (see for example Mueller Reference Mueller2011, Eddine Reference Eddine2012, and Bakken Reference Bakken2017 for studies on crosslinguistic influence from Spanish/Chinese/Korean, French, and Norwegian). Different types of evidence have been used to argue for crosslinguistic influence in the L2 (Jarvis Reference Jarvis2010), such as homogenous patterns of language use within a group of L2 users with the same L1, but heterogeneous patterns between groups of L2 users that have different L1s. Other types of evidence for crosslinguistic influence are cross-language congruity (similarity between language use in the L1 and in the L2) and intralingual contrasts (features that differ between the L1 and the L2).

However, crosslinguistic influence is not solely a characteristic of L2 language use. In multilingual language users, a second or any number of additional languages may also influence the L1 (Cook Reference Cook and Cook2003). Influence from L2 onto L1 has been observed in all areas of language structure, including phonology, morphosyntax, lexicon, and pragmatics (Pavlenko Reference Pavlenko2000, Cook Reference Cook and Cook2003). The influence may be temporary or permanent and range from borrowing transfers (such as lexical borrowings) to loss of the ability to produce certain L1 elements due to L2 influence (Pavlenko Reference Pavlenko and Cook2003). Attested examples of L2 influence on the L1 also include restructuring transfer and shifts (for example semantic extension), as well as convergence, the creation of a unitary system which is distinct from both the L1 and the L2 (Pavlenko Reference Pavlenko and Cook2003). Examples of crosslinguistic influence from L2 English on Scandinavian languages include influence on phraseology (Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb, Furiassi, Pulcini and Rodríguez González2012 on Danish) and vocabulary (Sundqvist Reference Sundqvist2009 on L1 Swedish).

In studies of crosslinguistic influence, not all types of evidence are feasible to obtain (Jarvis Reference Jarvis2010). Our study focuses on intralingual contrasts, discussing when the non-standard use of a preposition in Danish corresponds to its typical use in English or not. It is reasonable to assume that the L1 and L2 Danish texts in our study will both exhibit crosslinguistic influence from English. The L2 users have English as L1 and the L1 users are high school students who have been taught English as a foreign language since primary school. They are frequently exposed to English in Danish and foreign media. Influence from English in the written production of Danish by L1 users has been observed for individual words as well as phrases (Sørensen Reference Sørensen and Akhøj Nielsen2010, Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb, Furiassi, Pulcini and Rodríguez González2012). Additionally, young people living in Denmark tend to have positive attitudes towards loans from English (Heidemann Andersen Reference Heidemann Andersen, Widell and Kunøe2003) and may therefore be inclined to accept and produce calques from English.

Danish and English prepositions are similar in prototypical meaning but differ in extended meanings (see Section 2.1). In some cases, the cognates and partial overlap between Danish and English prepositions may facilitate production, especially in cases where the prepositions denote prototypical meanings. In other cases, calquing from English may conflict with the norms of standard Danish, for example with respect to prepositional choice and the valence of verbs (Gottlieb Reference Gottlieb2004). Yet, crosslinguistic differences and similarities cannot account for all variation in preposition usage. Previous studies of L2 users have shown that structures that differ from their L1 are not necessarily challenging, and that non-standard L2 usage also occurs in areas where the L2 structure corresponds to their L1 (Eckman Reference Eckman and Jung Song2011:620). Thus, we cannot assume a priori that they will struggle with Danish prepositions that have a different distribution than their cognates in English, and we cannot assume that L2 texts will conform to standard usage of Danish in sentences where the preposition use corresponds to equivalent English sentences. Section 2.3 is concerned with non-standard usage of valence-bound prepositions and Section 2.4 concerns prepositions with temporal meaning. Both types are mentioned by Lund (Reference Lund1997) as specific challenges to L2 learners of Danish, and we therefore explore whether the patterns of L2 users are distinct from those of L1 users. The third type of non-standard preposition usage is that of word class confusions, which we see as related to phonological similarity. There are, to our knowledge, no previous studies on confusion of prepositions with non-prepositions, but our data suggest that it is a relevant category to explore.

2.3 Crosslinguistic influence for valence-bound prepositions

In valence theory, obligatory complements are ‘those complements needed to form a grammatical sentence with the governing word (in a particular sense)’ (Herbst et al. Reference Herbst, Heath, Roe and Götz2004:xxxi). Prepositional phrases can be obligatory complements to verbs, adjectives, and nouns, and thereby part of their valence patterns. In these cases, the verb, adjective, or noun may select a specific preposition. Verbs that select a specific preposition are also known as prepositional verbs in some theories (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1972:811; Vestergaard Reference Vestergaard2019). In example (1), the verb believe selects in, while the adjective keen selects on in (2).

A valence-bound preposition cannot be exchanged with a different preposition (*believe on science). Still, the meaning of the prepositions is opaque in (1) and (2), compared to prototypical spatial uses where in clearly expresses containment (in the box) and where on clearly expresses contact/support (on the table). The English expression in (1) translates to Danish tro på and in this case, the proto-scene of the preposition på involves contact/support, rather than containment. This arbitrary crosslinguistic difference in choice of preposition illustrates the challenges for L2 users. Lund (Reference Lund1997) argues that specifically the opaque semantics of valence-bound prepositions makes them more challenging to learners of Danish as L2 than non-valence-bound prepositions whose semantics are more transparent.

We therefore examine whether valence-bound prepositions are a specific challenge to L2 users. The analysis focuses specifically on prepositions bound by verbs and adjectives since valence-bound prepositions are more frequent with verbs and adjectives than with nouns and because the valence patterns of nouns are not as well-defined.

2.4 Differences between spatial and temporal uses of prepositions

Temporal prepositions have been described as semantically less transparent than spatial uses of prepositions (Lund Reference Lund1997). From this perspective, the temporal use of prepositions is seen as a type of extended use, assuming that the domain of time is understood through the domain of space (Lakoff & Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999, Tyler & Evans Reference Tyler and Evans2003, Johansson Falck Reference Johansson Falck2014). The spatial use of the preposition in in the box clearly expresses a containment relation. In temporal uses, such as in May, the understanding of May as a container relies on a TIME is SPACE metaphor (Lakoff & Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999).

According to Lakoff & Johnson (Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999:153) a fixed duration of time can be understood as ‘a bounded region on a path along which an observer moves’ and can either be conceptualized as a container or as a point location along a line. It is, however, not entirely semantically transparent why some fixed durations of time are conceptualized as containers (in May, in the afternoon), while others are conceptualized as point locations (on Monday, at noon, at Easter).

Although related languages tend to have the same spatiotemporal metaphors, such as the TIME ORIENTATION metaphor, the MOVING TIME metaphor and the MOVING EGO metaphor, the conceptualization of temporal units differs, even between closely related Germanic languages (Lakoff & Johnson Reference Lakoff and Johnson1999, Durrell & Brée Reference Durrell, Brée and Zelinsky-Wibbelt2011, Johansson Falck Reference Johansson Falck2014). For instance, in contrast to English, the Danish sentence Hun løb 10 kilometer på 30 minutter ‘She ran 10 kilometres in 30 minutes’, employs the preposition på ‘on’, rather than i ‘in’ (for an overview of Danish prepositions employed in expressions of time compared to English, see Lundskær-Nielsen & Holmes Reference Lundskær-Nielsen and Holmes2011:165–166).

Lund (Reference Lund1997) suggests that L2 users of Danish acquire spatial uses before temporal uses, since temporal uses are more semantically opaque. Later results from empirical studies of other languages, however, have provided little support for the hypothesis that L2 users acquire spatial uses before temporal uses and instead point to the role of collocational strength, frequency, and similarity to prepositions in the L1 (Lam Reference Lam2018). One could suspect that temporal preposition phrases such as i dag ‘today’ and på mandag ‘on Monday’ would be acquired earlier simply because they are frequent (in usage and in classrooms) and often lexicalized. To further investigate this matter, our study examines whether the share of non-standard tokens in Danish L2 texts is higher for temporal uses than for spatial expressions and for non-spatiotemporal uses.

2.5 Aims and hypotheses

We carry out a comparative analysis of non-standard preposition usage in L1 and L2 texts, focusing on the differences that can be found in the use of spatial vs. temporal prepositions, valence-bound vs. non-valence-bound prepositions, and word class confusion. We expect that there is non-standard use of prepositions in both L1 and L2 texts.

In the quantitative part of the study, we also test the following two hypotheses, which are inspired by Lund’s (Reference Lund1997) acquisition hierarchies for L2 Danish.

-

In the L2 texts (but not the L1 texts), prepositions bound by verbs and adjectives will have a higher share of non-standard tokens than other types of prepositions.

-

In the L2 texts (but not the L1 texts), temporal uses will have a higher share of non-standard tokens than spatial expressions.

In the qualitative part of the study, we consider possible calquing from English.

3. Data and method

The data analysis is based on L1 data collected by the Danish Language Council and L2 data collected by the research group Broken Grammar and Beyond at the University of Copenhagen. The study was approved by The Faculty of Humanities Research Ethics committee at University of Copenhagen. All participants signed a consent form.

From a larger main corpus, we subtracted two sets of data with an equal number of informants shown in Table 1. The informants in both groups wrote bound topic essays for exam purposes, but the L2 group handwrote their essays, while the L1 group used computers. As shown in Table 2, the L2 texts are shorter than the high school texts. The L1 corpus contains more than 7 times as many running words. Our analysis takes this discrepancy into account. In essay writing, participants are not coerced to describe the same States of Affairs, so unlike controlled fill-the-gap tests and picture description tasks, we do not have a precise measure of how they would express the exact same content. Consequently, it is difficult to assess intra-group homogeneity.

Table 1. L1 and L2 writers in the corpus

a Here, British covers the language of writers from England, Ireland, and Scotland.

Table 2. The L1 and L2 texts in the corpus

The two groups differ in many aspects, but they have at least three important things in common: (i) the writers must adhere to language norms to pass their exam, (ii) the writers may be uncertain of norms, and (iii) the writers may be under crosslinguistic influence from English (or other known languages).

3.1 Annotation of prepositions in the corpus

Each text in the corpus was proofread and annotated by two linguists at the Broken Grammar and Beyond research project at University of Copenhagen. The proofreaders annotated and categorized all occurrences of non-standard language usage (whether related to prepositions or not) using XML and suggested how the text could be corrected. The tokens that were marked up included non-standard orthography, non-standard word order, and non-standard use of morphology and lexicon. The proofreaders consulted Danish dictionaries and grammars, other L1 users as well as Google searches to identify all occurrences that did not conform to the norms of standard Danish.

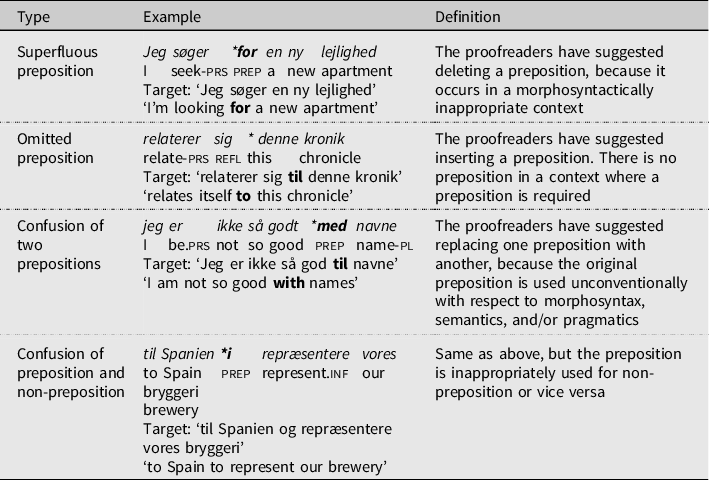

Using the fully annotated corpus, we extracted all tokens that involved non-standard use of a preposition (except for those that purely involved non-standard orthography such as spelling til as ti). We extracted all occurrences of the following three subtypes: omitted prepositions, superfluous prepositions, and the confusion of two prepositions. From this set of tokens, we analyzed only those cases that involved the four target prepositions: for, i, på, and til. In addition, we extracted all tokens that involved confusion between any of these four prepositions and a non-preposition (1 token in L1, 11 tokens in L2). Examples and definitions are shown in Table 3. The full set of non-standard tokens for individual participants is shown in Appendix A in the supplementary material.

Table 3. Definitions of non-standard usage involving the prepositions på, i, for, and til.

There is not much dialectal variation in written Danish, and dialect forms are not accepted in official writing as regulated by the Danish Language Council, Sprognævnet. Yet, sociolectal and idiolectal differences in the norms of preposition can make it difficult to distinguish non-standard cases that conflict with written norms from natural variation. In cases of doubt during our annotation, we erred on the side of caution and excluded the specific case from the analysis.

4. Analysis

Our analysis is partly quantitative (accounting for frequencies and potential error rates) and partly qualitative (accounting for patterns in the distribution of different types of non-standard usage). In both parts of the analysis, we distinguish between correct uses of a preposition (that adhere to written language norms) and non-standard usage (that conflict with norms). The non-standard tokens are either examples of overuse or underuse and have the following subtypes.

-

Overuse

-

a. Superfluous use of the target preposition

-

b. Incorrect use of the target preposition for another preposition

-

c. Incorrect use of the target preposition for a non-preposition (for example a conjunction)

-

-

Underuse

-

a. Omission of the target preposition

-

b. Incorrect use of another preposition for the target preposition

-

c. Incorrect use of a non-preposition for the target preposition

-

4.1 Quantitative analysis

We used linear mixed models (R version 4.1.1, package lme4) to test (i) whether prepositions bound by verbs and adjectives are more prone to non-standard usage in L1 and L2 than other prepositions, and (ii) whether temporal prepositions in L1 and L2 are more prone to non-standard usage than spatial prepositions. The dataset for these two analyses included all correct uses of the four target prepositions as well as tokens where a target preposition was omitted or confused with another preposition. For each token we annotated (i) whether the preposition was bound by a verb or adjective, and (ii) whether the use of the preposition was spatial, temporal, spatiotemporal, or none of these. Word class confusions (confusions between a preposition and a non-preposition) and superfluous uses of a preposition were not included in the dataset for these analyses, since such tokens cannot meaningfully be categorized as spatiotemporal or valence-bound.

4.2 Qualitative analysis

Throughout the qualitative analysis, we discuss whether crosslinguistic influence from English can be observed in the form of possible calques. A calque (or loan translation) can be defined as ‘a complex lexical unit (either a single word or a fixed phrasal expression) that was created by an item-by-item translation of the (complex) source unit’ (Haspelmath Reference Haspelmath, Haspelmath and Tadmor2009:39). The source unit may be lexical or morphosyntactic. In our study, sentences that are possible English calques are thus non-standard Danish sentences that look like near word-for-word translations (or preposition-to-preposition translations) of an equivalent English sentence as illustrated by example (3). Here the Danish preposition i is used instead of the target på in a context where the correct choice of preposition in English would be in.Footnote 1

In other cases, there are no indications of calquing. For instance, if we backtranslate the non-standard sentence in (4) to English from Danish, the result is not a grammatical sentence in English either (we shall meet *to my home).

In the English backtranslation, the correct preposition would be in, and in Danish its cognate preposition is i. In this case, it is therefore implausible that the use of til is due to crosslinguistic influence from English.

In some cases it is difficult to determine whether or not there are possible calques. Consider example (5), for instance.

In our analysis, we classified til as a superfluous preposition since the target form ‘Kan du besøge os?’ does not have a preposition. As indicated by the translation, we interpret the semantically equivalent English expression of the target form to be ‘visit us’. This translation implies that the sentence is not a possible calque. However, one could alternatively assume that the structurally equivalent expression would be pay a visit to us. By this analysis, the Danish sentence would express crosslinguistic influence from English.

5. Results

The four prepositions for, i, på, and til occur frequently and have 61 occurrences/1,000 words in the L1 corpus against 58 occurrences/1,000 words in the L2 corpus. When it comes to non-standard preposition usage, however, the share is higher in the L2 corpus (12 non-standard tokens/1,000 words) than in the L1 corpus (0.9 non-standard tokens/1,000 words). These frequencies are similar to those found for non-standard morphology in the corpora, specifically concerning adjective agreement (15 non-standard tokens/1,000 words in L2 texts vs. 0.9 in L1 texts) and verb conjugation (10.5 non-standard tokens/1,000 words in L2 texts vs. 2 in the L1 texts). In the L1 texts, 2.4% of all registered non-standard uses were related to for/i/på/til (35/1479). In the L2 texts, the share is 7.3% (70/958). Seven L1 users did not produce any non-standard uses related to the four target prepositions, and the remaining 19 L1 users each produced 1–5 non-standard tokens. In the L2 group, 4 users had no non-standard usage, and the remaining 24 L2 users each had 1–7 non-standard tokens.

In texts by both L1 and L2 writers, we find examples of non-standard uses involving superfluous, omitted, and confused prepositions (as defined in Section 3), and for both groups, confused prepositions are more frequent than superfluous and omitted prepositions. Table 4 shows the absolute number of non-standard tokens for each of the four prepositions. Note that since the L1 texts are longer than the L2 texts, the total occurrences of for/i/på/til were generally higher in the L1 texts (N = 2470) than in the L2 texts (N = 330).

Table 4. Non-standard usage of prepositions (superfluous, omitted, and confused) in L1 and L2 texts

While confusions involving all four prepositions are found in both groups, the distributional pattern is different. Table 5 compares the L1 texts and L2 texts with respect to the percentages of overuse and underuse of the four prepositions. In the L1 texts, på has the lowest percentage of underuse (0.7%), but in the L2 texts på is underused in 20% of all obligatory contexts, which makes it the most underused of the four prepositions. Table 4 and 5 also show that the L2 texts have a proportionally high rate of non-standard tokens related to the preposition til: there is both more overuse of til and more omissions of til than in L1 texts. This pattern may be due to influence from English, as we will discuss in Section 5.3.

Table 5. Overuse and underuse of for, i, på, til in L1 and L2 texts

Overused means superfluous or inappropriately used for another preposition or non-preposition. For each preposition, the percentage of overuse is all overused tokens divided by all (non-standard as well as correct) tokens in the relevant corpus. Underused means omitted or confused with a non-standard preposition or non-preposition. The percentage of underuse is all underused tokens divided by all obligatory contexts in the corpus.

5.1 Non-standard usage for valence-bound prepositions

Non-standard usage involving valence-bound prepositions is not specific to L2 users: they are also produced by L1 users, as illustrated in Figure 2 and Table 6.

Figure 2. Share of non-standard tokens for valence-bound and non-valence-bound prepositions.

Table 6. Non-standard uses for valence-bound and not valence-bound prepositions (bound by verbs or adjectives)

The table contrasts the share of non-standard tokens for valence-bound prepositions vs. not valence-bound. Non-standard shows the number of non-standard tokens (how many times the target preposition was omitted or a different preposition was used instead). Superfluous prepositions and confusions with non-prepositions and fixed expressions are not included in the table.

We conducted a statistical test to examine whether prepositions bound by verbs and adjectives have more non-standard usage in L1 and L2 than other prepositions. The data were all tokens in the two corpora with i/for/på/til as target preposition. We manually annotated the prepositions in each token as valence-bound or not. Tokens with fixed expressions (such as I forhold til = ‘regarding’) as well as superfluous prepositions and confusions with non-prepositions were excluded from the analysis. Our binomial mixed model had correctness of use as its dependent variable (non-standard vs. correct usage). Its two fixed effects, both contrast-coded, were group (L1 vs. L2) and type of preposition (valence-bound vs. non-valence-bound). Participant and target preposition were random effects. The model (see Appendix B in the supplementary material) confirmed that L2 texts had more non-standard usage than the L1 texts across valence-bound and non-valence-bound prepositions (p < 0.001). Although Figure 2 seems to suggest that valence-bound prepositions have a higher share in both the L1 and the L2 group, the statistical model showed no significant difference in non-standard usage rates for valence-bound vs. non-valence-bound prepositions in any of the groups.

Table 6 shows that non-standard usage only occurs for 1% of all valence-bound prepositions in the L1 texts, compared to 25% in the L2 texts, but that the rates vary between the four prepositions. For instance, all 13 cases of valence-bound for in the L2 texts are correctly produced, but non-valence-bound for has 7 non-standard tokens. This is the opposite pattern to the L1 texts, where the non-standard rate is lower for non-valence-bound than for valence-bound prepositions, such as (6). This L1 sentence contains a possible calque, as argumentere always selects the preposition for, unlike its English counterpart argue which does not select a preposition.

In the L2 texts, there is only one obligatory context where i is valence-bound (enig i at ‘agree that’) and a non-standard rate of 100% since i is omitted (enig * at). This omission is also a possible calque as the English counterpart of the Danish expression enig i at ‘agree that’ does not require a preposition.

The highest numbers of non-standard uses for valence-bound prepositions in the L2 texts relate to the prepositions på and til. In four cases på is confused with another preposition. Three of these cases involve the verb tænke ‘think’, which seems challenging to L2 writers but not L1 writers. While English think selects of or about, Danish tænke selects på. This may explain why L2 writers use non-standard combinations that are possible English calques, such as tænke af and tænke om (the prepositions af and om usually translate to ‘about’). In the L1 texts, there is only one non-standard token involving valence-bound på.

Til only accounts for one non-standard token in the L1 texts and it does not seem related to influence from English (see Section 5.3). While there are no indications of influence from English on non-standard til usage in the L1 texts, there are some in the L2 texts. Unlike its English homograph, the Danish verb ring requires a preposition with the object. This may explain why there are two cases of omitted til after ring. One of them is shown in (7).

In summary, indications of possible influence from English are found for most of the non-standard tokens in both the L1 and L2 texts, but manifest with different prepositions and different expressions. In the L2 texts, 5 out of 8 non-standard uses for valence-bound prepositions involve the expressions tænke på and ring til, which are always correct in the L1 texts. According to the statistical test, neither group has more non-standard usage of valence-bound prepositions compared to non-valence-bound prepositions.

5.2 Non-standard usage involving spatial and temporal meaning

As illustrated in Figures 3 and 4, we find cases of all four prepositions with spatial and temporal meaning in both the L1 and L2 texts. Both groups have non-standard usage of spatial and temporal relations, but the share is higher in the L2 group. The figures show all correct uses of for/i/på/til in grey and all non-standard uses where for/i/på/til is target or superfluous in red.

Figure 3. The frequency of non-standard tokens for spatial use of prepositions.

Figure 4. The frequency of non-standard tokens for temporal use of prepositions.

We conducted a statistical test to examine whether expressions with temporal meaning had a higher share of non-standard usage than expressions with spatial meaning. The data for this analysis only included items that could clearly (by manual annotation) be categorized as spatial or temporal and that either had i/for/på/til as the target preposition or had a superfluous i/for/på/til. Our binomial mixed model had correctness of use as its dependent variable (non-standard or correct use) and two independent variables: group (L1 vs. L2) and use of preposition (spatial use vs. temporal use), which were both contrast-coded. According to this model (see Appendix B in the supplementary material), the L2 group had significantly more non-standard tokens for spatiotemporal prepositions than the L1 group (p > 0.001). However, none of the groups had more non-standard tokens for temporal uses than the other. As mentioned in Section 2.4, frequent temporal lexicalized preposition phrases such as i dag ‘today’, i går ‘yesterday’, and i morgen ‘tomorrow’ may be acquired earlier and therefore exhibit less non-standard usage. However, a subsequent analysis excluding these expressions did not lead to a different result.

The four prepositions differ with respect to the frequency of non-standard usage. Figures 3 and 4 show that for and til in spatiotemporal expressions are rarely confused or omitted. In the L2 texts, the main challenge seems related to prepositional phrases involving a public place. For physical buildings, Danish uses i, as in i biblioteket på 2. sal (‘in the library on the second floor’). For public places conceptualized as an institution or a community rather than a specific building, på is preferred, as in låne bøger på biblioteket, literally ‘borrow books on the library’ (see Lundskær-Nielsen & Holmes Reference Lundskær-Nielsen and Holmes2011:166–167 for more examples of Danish prepositions indicating locations and institutions).

Non-standard use of i for på with a public place such as hostels, cafés, and museums as in (8) is seen 5 times in the L2 texts, and in 2 cases til is used for på with a public place, as shown in (9).

Besides underuse of på, there is one L2 example of overuse for a non-public building where i is the correct preposition (vi var op *på summerhuset ‘we were up at the summerhouse’).

The L1 texts only have one non-standard token where i is used for på with a public place shown in example (10), but possible calques also occur for other types of non-standard tokens involving spatial meaning. For instance, one L1 user uses til instead of i in går i kemoterapi ‘go to chemotherapy’.

Non-standard uses with temporal meaning are rare in the L1 texts. There are only two cases, one of which is shown in example (11).

In the L2 texts, there are 8 non-standard cases for temporal meaning. Only 2 cases involving på are possible calques. Unlike English, Danish does not use prepositions before dates, so på is superfluous in * på den første april ‘on the first of April’ and * på 3. Februari ‘on the 3rd of February’. The other six cases are not possible calques. For instance, the superfluous i in (12) does not correspond to the use of in in English (where at 18.30 is correct and in 18.30 is not).

Both the L1 and L2 texts have superfluous and omitted tokens for spatial and temporal meaning. In the L2 texts, all the superfluous and omitted tokens seem related to word class confusions and will be discussed in Section 5.3.

In summary, both groups to some extent use possible calques when confusing spatiotemporal prepositions. In the L2 texts, calques are especially frequent for spatial relations involving public places. Overall, the L2 texts have a higher share of non-standard uses for spatiotemporal prepositions than the L1 group. Yet, contrary to our expectations based on Lund’s (Reference Lund1997) hypothesis (see Section 2.4), the rate for confusions and omissions in the L2 texts is not higher for temporal meaning than for spatial meaning.

5.3 Word class confusions

Through exploratory analysis, we discovered that word class confusions are a characteristic feature of the L2 texts. Word class confusions include the use of non-prepositions instead of prepositions, the use of prepositions instead of non-prepositions, as well as non-standard preposition usage that may arise from inappropriate word class assignment of neighboring words.

In particular, the preposition til tends to be overused for non-prepositions. The English preposition to and the English infinitive marker to are homonyms, but in Danish the preposition til and the infinitive marker at bear no phonological resemblance to each other. The homonymy between the English preposition to and the infinitive marker to may explain why we find 6 cases of possible calquing where L2 writers use Danish til in lieu of the infinitive marker at, as in (13).

Other possible calques with til and at include six cases where til is omitted in front of an infinitive marker. In (14) the Danish target requires that the infinitive marker at is preceded by the preposition til (til at gøre), which directly translates to ‘to to make’.

Finally, there are three cases where a superfluous til directly precedes the infinitive marker at, as in example (15). While this example is not a possible calque of English, it shows that even L2 writers who use the Danish infinitive marker at seem unsure of when til can collocate with an infinitive.

Non-standard usage involving infinitive construction such as examples (13)–(15) may help explain why the L2 texts overall have a much higher share of non-standard tokens related to til than the L1 texts as discussed above. These non-standard uses are most likely caused by the phonological similarity between the preposition to and infinitive marker to in English.

In some cases, omission of prepositions could be caused by inappropriate word class-assignment of preceding words. In example (16), the adverb rundt is used as a preposition in a context where an English backtranslation would have used the preposition around. While the English word around can function as both an adverb and preposition, Danish rundt can only function as a spatial adverb (or an adjective) – never as a preposition.

We do not see non-standard usage involving adverbs such as rundt or similar cases in the L1 texts. These kinds of word class confusion between words whose phonological form is similar in English, seems characteristic of L2 users only and may indicate retention of L1 phonology.

5.4. Other observations

As discussed above, there are several semantic factors that might influence the distribution of non-standard preposition usage, of which we have mainly focused on the distinction between spatial and temporal prepositions.

Both L1 writers and L2 writers produce non-standard tokens in constructions where the prepositions for and til either designate the purpose of an action or the goal of either an emotion or action, such as cook for somebody, appear to somebody, throw a party for somebody, or love for somebody. In the L2 texts there are four examples of L2 writers using for instead of the correct preposition til in such a context, one of which is shown in (17), where for is used to designate the purpose (an important meeting) of an action (going to an office). All four cases are possible calques, as the English equivalent expressions use the preposition for.

Similarly, the L1 texts have five examples of for, med, or på used instead of til, one of which is the possible calque shown in (18) where for is used to designate the goal (herself) of an action (taking money).

Additionally, the L1 texts have two cases of til used instead of for, as exemplified in (19) which is not a possible calque.

6. Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we took the first steps towards documenting the characteristics of non-standard usage of prepositions in written Danish. The main objective was to analyze and compare the distribution of non-standard usage involving på, i, for, and til in natural texts written by L1 and L2 Danish users (with English as their L1). Non-standard usage occurred in both groups. In the following sections we discuss the similarities and differences between the L1 and L2 texts and the limitations and perspectives of the study.

6.1 Similarities between L1 and L2 texts

The study showed that prepositions are used in non-standard ways whether the writer has Danish as L1 or L2. Awareness of the specific challenges concerning the normative use of prepositions for these two groups is valuable for focused teaching of grammar and writing skills in Danish high schools and language schools.

In both groups, confusions between two prepositions occur more often than superfluous prepositions and omitted prepositions. Both groups have non-standard usage for valence-bound prepositions, and both have non-standard tokens for spatial and temporal uses of prepositions. Possible calques occur in both groups, for example with confusion of for and til.

Lund (Reference Lund1997) proposed that L2 users acquire valence-bound prepositions later than non-valence-bound ones. However, our data do not support this proposed acquisition hierarchy, as we find no significant difference between the share of non-standard tokens for valence-bound and non-valence-bound prepositions in the L2 texts. It should be noted that the L1 texts use a wider range of verbs and adjectives than the L2 texts. The share of non-standard tokens for valence-bound prepositions in L2 writers may be low, simply because L2 writers are not familiar with the same range of verbs and adjectives as L1 writers. We therefore suggest that further studies explore the usage of valence-bound prepositions in more advanced L2 learners.

Lund (Reference Lund1997) also proposed that temporal prepositions are acquired later than spatial prepositions, based on the assumption from cognitive linguistics that the meaning of temporal prepositions is abstract and derived from the meaning of more concrete spatial prepositions. Our results, however, showed no significant differences in the share of non-standard tokens for spatial and temporal prepositions – either in the L1 or in the L2 texts. Our results align with other L2 acquisition studies that find that spatial prepositions are not acquired before temporal prepositions (see Lam Reference Lam2018 for a review). Similarly, Saravanan (Reference Saravanan2015) has shown that Tamil writers of L2 English are challenged more by spatial preposition than temporal prepositions.

We expected that not only the L2 writers but also the L1 writers would be influenced by English, as L1 users of Danish are regularly exposed to English in the media and have learned it from an early age. Our results confirmed that possible calques are not unique to the L2 writers. Although the L1 writers had internet access and access to dictionaries, their texts did not adhere completely to the norms for preposition usage in Danish. Non-standard tokens were found in many of the same domains, such as valence-bound and spatiotemporal prepositions, in L1 and L2 texts.

6.2. Characteristics of L2 texts

The main distinctive feature of the L2 texts is that non-standard uses are much more frequent than in the L1 texts. In addition, the L2 texts had a higher share of tokens related to for/i/på/til (7.3%) than the L1 texts (2.4%) when compared to other types of non-standard language use in the texts (for instance verb conjugation). These results are in line with the common assumption in the literature that prepositions as such are challenging to L2 learners (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman Reference Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman1999, Lorincz & Gordon Reference Lorincz and Gordon2012, Lam Reference Lam2018). Our study involved learners with relatively low proficiency in Danish (CEFR A2-B1), so it remains unsolved whether prepositions continue to be particularly challenging for L2 users at higher proficiency levels or become on a par with L1 users.

Non-standard uses related to word class confusion are only found in L2 texts. The L2 texts are prone to over- or underuse prepositions when there is homonymy between prepositions and other word classes in English, but not in Danish. For instance, the homonymy between the English preposition to and the infinitive marker to in English could be a cause for non-standard usage involving the Danish preposition til and the infinitive marker at. The prevalence of word class confusions in the L2 texts can be taken as an indication that English phonology is at play in the writing of the L2 users, but not in that of the L1 users. This finding is in line with a claim from studies of contact languages and language change. According to Haspelmath (Reference Haspelmath, Haspelmath and Tadmor2009), crosslinguistic influence in contact-induced language change tends to manifest itself in different ways in the language of L1 users compared to the language of L2 users. Similar to our findings, language change studies show that it is characteristic of L2 users to retain the phonology of their L1.

6.3 Limitations and perspectives

The study was based on a small sample, which naturally limits the conclusions that can be drawn. As discussed in Section 3, the text types produced in the two groups were rather different. The L2 writers wrote short informal texts such as emails while L1 writers wrote longer academic texts analyzing short stories or newspaper articles. The differences in text types may influence the types of prepositions used by writers. For instance, the L2 texts are often emails about arranging an activity and therefore frequently mention time and place. The topics of the L1 texts are more abstract and include quotes that are typically accompanied by a preposition referring to a line number or section.

Non-standard usage in L2 texts is not always present due to crosslinguistic influence. It may also be due to, for instance, the L2 user having been exposed to variation in use of Danish prepositions. Further studies of the non-standard use of prepositions by L2 Danish writers with another L1 than English may shed further light on what is attributable to the language-specific structure of written Danish and which problems are more likely caused by crosslinguistic influence from other languages known by the writer. An especially interesting area for further study is the case of word class confusions, which our study indicates is an L2 user phenomenon that may be caused by influence from the phonology and grammar of the L1. To our knowledge, word class confusions have not received much attention in the literature. Since this specific kind of homophony is also found in other languages such as German (which has the preposition zu ‘to’ and the infinitive marker zu ‘to’), German L2 users of Danish could potentially produce the same kinds of word class confusions. We also expect that L2 users of other prepositional languages than Danish could confuse prepositions with non-prepositions based on phonological similarity in their respective L1. We therefore suggest focusing on word class confusions related to L1 phonology in future L2 research and in the L2 classroom.

Further studies of preposition usage in Danish L1 texts are also needed. In our study, the L1 users were adolescent high school students and the variation in their usage of prepositions may be different from that of more mature language users. While both groups can be assumed to have random occurrences of non-standard usage (e.g. due to typos and editing errors), there may also be some types of variation that are sociolectal and specific to this group of young L1 users. There may, for instance, be differences in writing experience and in exposure to English. As for both young and mature writers, some variation in the use of prepositions may reflect linguistic variation and ongoing language change in the Danish speech community as a whole. Our results support the general importance of including naturally occurring L1 production as a baseline for describing characteristics of L2 production, rather than comparing to idealized L1 production. Often the L1 users in our study did not follow the norm. L2 users would have to outperform Danish high school students to meet a perfect standard of preposition usage, and that seems excessive for learners at levels A1–B2. We therefore recommend that language tests of L2 Danish allow for some variation in preposition usage. Rather than meeting a perfect standard, successful L2 acquisition entails developing a language with an L1-like share of naturally occurring non-standard uses.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0332586523000136