Introduction

This article examines representation within cabinet committee structures in Canada from 2003 to 2019, under prime ministers Paul Martin, Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau. It focuses on gender and region as two politically salient aspects of diversity representation in Canada and on ministerial influence within the structure of cabinet committees. Previous scholarship has scrutinized the question of ministerial appointment in Canada and elsewhere (for example, Dowding and Dumont, Reference Dowding, Dumont, Dowding and Dumont.2015; Kerby, Reference Kerby2009, Reference Kerby2011). Scholars have also examined gender as a specific representational concern for prime ministers or presidents in crafting their cabinets (for example, Annesley et al., Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014; Krook and O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012), and regional representation is central in the Canadian context (White, Reference White2005; Kerby, Reference Kerby2009). The role of representation in shaping ministerial careers has also been examined (for example, Tremblay and Stockemer, Reference Tremblay and Stockemer2013; White, Reference White1998). Yet there has been little attention to the role of representation in determining ministerial influence within cabinet decision making after appointments are made. To what extent does gender and region determine a minister's place in the cabinet “pecking order”? I address this gap in scholarship through the lens of ministerial positions within structures of cabinet committees.

Cabinet committees are central mechanisms of cabinet deliberation and decision making in Canada. Insofar as cabinet plays a meaningful role in governance, its influence primarily occurs through these subgroups of ministers with coordinating or policy-specific responsibilities. Committees are delegated significant autonomy to make authoritative decisions, subject to confirmation by cabinet but otherwise all but guaranteed (Privy Council Office, 2015: 36–38; Savoie, Reference Savoie1999: 128). Despite their importance, cabinet committees are understudied and rarely attract public notice, in part because they operate behind closed doors. Historically, even acknowledgment of their existence or membership was deemed to be “purely internal” and subject to cabinet confidence (Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy and Dunleavy1995: 302; see also Koerner, Reference Koerner1989: 11–12).

If cabinet committees are important, how they reflect aspects of Canadian diversity should also be important. Using committee membership data over the period 2003 to 2019 and tools of social network analysis, I assess the degree to which two core representational aspects—gender and region—are reflected in cabinet committee structure. For gender, I find that female ministers are less likely than male ministers to be highly connected to other ministers, to be a part of the “core” of most influential ministers and to sit on the most important committees and/or chair committees. Overall, then, female ministers are less likely to be influential than male ministers, though the effect of gender depends on the “supply” of female ministers; thus, women's representation has improved over time. The role of regional representation in determining ministerial influence within cabinet committees is highly limited. Ministers from less-represented regions are no more likely to be influential than other ministers, and it does not appear that prime ministers systematically seek regional balance in the distribution of ministerial influence.

I proceed as follows: First, I describe cabinet committees and their development in Canada. Second, I survey what we know about gender and regional representation in cabinet and cabinet committees and identify corresponding empirical expectations. Third, I discuss the data and methodological approach of the study. Fourth, I relate the study's empirical results. Finally, I discuss these results and conclude.

Cabinet Committees in Canada

Cabinet committees are small subgroups of cabinet ministers, with their structure, processes and membership at the discretion of the prime minister. Their basic function is to consider matters within their responsibilities and make recommendations to cabinet. Committees are structured around coordinating responsibilities or policy mandates (Koerner, Reference Koerner1989: 10). Coordinating committees set overall strategic directions or manage the government's agenda and are considered the “inner” committees, significantly more powerful and decisive than other committees (Everitt and Lewis, Reference Everitt, Lewis, Tremblay and Everitt2020: 201). Historically, the pre-eminent coordinating function resided in the Priorities and Planning committee; the current equivalent is Agenda, Results and Communications. The coordinating committees include the most senior ministers and are chaired by the prime minister as a rule; this is both cause and consequence of the increasing centralization of power in Canada (Brodie, Reference Brodie2018: 73; White, Reference White2005: 149). Policy committees are assigned specific policy areas or goals. Interestingly, while policy committees include relevant ministers, they are often not chaired by the most relevant minister. For example, the Reconciliation committee is not chaired by the minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations, Indigenous Services or Northern Affairs but by the minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion. Indeed, recent changes suggest a greater focus on the coordination of committee business: membership on the Operations committee is now specifically limited to committee chairs, which was not the case previously.

Cabinet committees have largely superseded cabinet as a tool for collective decision making in Canadian government (Ie, Reference Ie2019; White, Reference White2005: 148–49). Indeed, since the late 1960s, cabinet committees have been delegated significant authority to take decisions on behalf of cabinet; such decisions have rarely been challenged in full cabinet (Savoie, Reference Savoie1999: 128; White, Reference White2005: 148). This delegation arose from a functional need to rationally manage the work of cabinet as the size and complexity of government increased in the postwar period. Cabinet and cabinet business correspondingly grew, limiting the feasibility of collective cabinet decision making. Committees could study issues and take decisions more effectively and efficiently because of their size and focused mandates, while allowing cross-departmental scrutiny and whole-of-government consideration. At the same time, the system of committees allows the prime minister and Privy Council Office, through which committee business operates, greater oversight. Thus, committees serve two different but complementary purposes: they allow ministers to have meaningful input and influence, while increasing centralized control and countering departmentalism and fragmentation (Ie, Reference Ie2019). Committees may also be politically useful as a “way of reassuring the public, and government, of the executive's commitment to address important issues” (Catterall and Brady, Reference Catterall, Brady and Rhodes2000: 161).Footnote 1 As central decision-making bodies within the Canadian executive, cabinet committees should be important sites of representation.

Gender and Regional Representation in Cabinets

This study builds on literature examining diversity of representation in cabinet appointments. While cabinet committees are key sites of executive decision making, analysis of their representational aspects is almost nonexistent. This review, then, focuses on gender and regional representation in cabinet generally, which is itself not merely a mechanism for deliberation and decision making but a “representative or legitimating institution” (Koerner, Reference Koerner1989: 3). While regional and linguistic representation has been at the forefront of cabinet making since Confederation, the salience of women's representation in Canada and elsewhere has increased significantly only in recent decades (Annesley et al., Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019; Kerby, Reference Kerby, Dowding and Dumont.2015: 274). Justin Trudeau's appointment of a gender-balanced cabinet in 2015 earned praise and support (Franceschet et al., Reference Franceschet, Annesley and Beckwith2017: 488), particularly because previous cabinets were significantly less impressive in this regard; progress has been “slow and incremental” (Everitt and Lewis, Reference Everitt, Lewis, Tremblay and Everitt2020: 193). In the cabinet immediately prior to the first one for which data was collected, 7 of 27 members were women (26 per cent), comparable to Martin and Harper cabinets; the share declines backward over time. Jean Chrétien's first cabinet in 1993 was 22 per cent female; Kim Campbell's cabinet, 21 per cent; Brian Mulroney's, 15 per cent; and the last Pierre Trudeau cabinet, 6 per cent (Young, Reference Young, Trimble, Arscott and Tremblay2013: 262). Overall, Canada still lags other peer countries such as Finland and Sweden, as well as developing countries such as Rwanda and Nicaragua (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2020). Globally, as of January 1, 2020, in only 16 per cent of countries do women hold 40 per cent or more of the ministerial positions; the average is 21.8 per cent (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2020).

Many studies of women's representation in cabinets focus on identifying the contributing political, normative and structural factors. The “supply” of potential cabinet ministers in the governing caucus and the legislature has been found to be significant: the more women elected to legislative office, the more likely they are to be appointed as ministers (Claveria, Reference Claveria2014; Krook and O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012; Siaroff, Reference Siaroff2000; Studlar and Moncrief, Reference Studlar and Moncrief1997). Goddard (Reference Goddard2019b) finds that female leaders are substantially more likely to appoint female ministers; however, a study using similar though not identical cases found that female prime ministers were associated with fewer women appointed (O'Brien et al., Reference O'Brien, Mendez, Peterson and Shin2015). The claim that left-wing leaders and governments are more likely to appoint women to cabinet is robustly supported (Claveria, 2014; Goddard, Reference Goddard2019b; Siaroff, Reference Siaroff2000), though Stockemer and Sundström (Reference Stockemer and Sundström2018) present a more mixed picture. Annesley et al.'s (2019) recent contribution closely examines the process of appointment, arguing that deficits in women's representation are caused by implicit gender bias in the use of “affiliational” criteria (the personal networks of selectors) and “experiential” criteria (the perception of what merit qualifies one for cabinet). Conversely, increasing representation requires delegitimizing “selectors’ use of affiliational and experiential criteria to appoint all-male cabinets exclusively from their networks of trust and loyalty” (Annesley et al., Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019: 250). Selector agency is crucial: women's representation has lagged where there have been no selectors willing to use their discretion to appoint more women (251).

While Krook and O'Brien (Reference Krook and O'Brien2012) argue that broader gender equality norms do little to explain female ministerial appointment, Jacob et al. (Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014) find that the effect of international norm diffusion, such as the adoption of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, is stronger for cabinet appointment than legislative representation. Goddard (Reference Goddard2019b) also finds that gender-equal cultural contexts are positively associated with cabinet representation. The role of structural factors, such as constitutional and electoral-system type and specialist-versus-generalist systems of ministerial appointment, has been assessed (Claveria, 2014; Krook and O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012; Siaroff, Reference Siaroff2000). The latter is especially interesting in finding that systems that tend to have ministers chosen for specialized expertise, rather than political skill, service or loyalty, tend to have stronger female representation (Annesley, Reference Annesley2015).

Finally, a sizable literature examines the question of effects of women's representation—particularly the specific portfolios to which women are appointed—and policy or behavioural outcomes. When women are appointed to cabinet, do they hold senior, important portfolios or are they assigned relatively minor roles? Does women's representation impact policy outputs or gender norms and attitudes? The gendered pattern of portfolio allocation refers to women being assigned traditionally “feminine,” “low-prestige” roles, such as health, family and education policy, while men retain higher-status portfolios related to finance, security and foreign policy (Krook and O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012: 842). In Canada, for example, a woman had never been appointed minister of finance, typically the most senior cabinet position, until Chrystia Freeland in 2020.Footnote 2 Studlar and Moncrief (Reference Studlar and Moncrief1999) find that in provincial cabinets, women were underrepresented in the “most important” portfolios and overrepresented in “junior” portfolios, but also a positive time trend. Trimble and Tremblay (Reference Trimble and Tremblay2005: 39) confirm this in assessing federal and provincial ministers from 1917 to 2002. In a study of 29 European countries, Goddard (Reference Goddard2019a) also shows that while women are less likely to be appointed to “high salience” and traditionally “masculine” or “neutral” policy responsibilities, the effect is moderated by party ideology. Jacob et al. (Reference Jacob, Scherpereel and Adams2014), while finding that gender equality norms are associated with ministerial appointment, also show a significant degree of “tokenism,” in that it is low-prestige posts that are most strongly impacted by norm diffusion.

Evidence about women's representation and policy or behaviour generally shows impact, though not always as expected. Higher cabinet representation is associated with longer parental leave, “female-friendly” work regulations, state-provided childcare and higher public health spending (Atchison and Down, Reference Atchison and Down2009; Atchison, Reference Atchison2015; Mavisakalyan, Reference Mavisakalyan2014). However, Koch and Fulton (Reference Koch and Fulton2011) show that higher defence spending and conflict behaviour are more likely when women are either the chief executive or defence minister. While some studies find that women's representation has positive effects on women's political participation (Liu and Banaszak, Reference Liu and Banaszak2017) and satisfaction with government (Barnes and Taylor-Robinson, Reference Barnes, Taylor-Robinson, Alexander, Bolzendahl and Zalalzhai2018), the latter also shows no positive effect on attitudes about women's ability to lead. Beauregard (Reference Beauregard2018) also does not find women's representation in cabinet to positively affect gender gaps in political participation.

Because this study involves a single case, it cannot test many of the factors identified above for lack of variation. However, it informs debates about the role of gender within the core executive and a key mechanism within the policy-making process, which Annesley and Gains (Reference Annesley and Gains2010) argue has been neglected. The literature leads to the expectation that female ministers are less likely to be influential within the domain of cabinet committee structure than their male counterparts, even as gender has become a more salient consideration in determining ministerial appointment. We also expect, though, that context and time matter: as women have increasingly entered ministerial positions in Canadian cabinets over time, the supply factor kicks in. In other words, the expected negative effect of being a female minister on ministerial influence decreases as cabinets approach gender parity.

The second aspect of representation examined in the cabinet committee context is region. Region is an important factor in cabinet selection both in federal systems, explicitly built on regional difference, and unitary systems such as New Zealand (Curtin, Reference Curtin, Dowding and Dumont.2015: 29). The pervasiveness of regionalism is a core reality in Canadian politics; appropriate regional representation in cabinet is considered a constitutional convention (Kerby, Reference Kerby, Dowding and Dumont.2015: 272; White, Reference White2005: 40–42). This “representational imperative” dictates that all regions constituting the Canadian federation should be at least minimally represented in cabinet. Historically, this has been reflected both descriptively and substantively through careful selection of ministers from each region and through regional ministers designated to articulate regional interests and manage party and government affairs in their regions (Bakvis, Reference Bakvis1989). Indeed, these ministers were an important mechanism of intrastate federalism: the channelling of regionally based interests through national government institutions (Smiley, Reference Smiley1977; Smiley and Watts, Reference Smiley and Watts1985). The most prominent of these, for anglophone prime ministers, was the “Quebec lieutenant”—figures such as George-Étienne Cartier (for John A. Macdonald) and Ernest Lapointe (for Mackenzie King)—but strong Atlantic and Western ministers have also existed (Bakvis, Reference Bakvis1988: 540).

While the salience of regional representation in Canadian cabinets is well established, its consequences for cabinet committees merit attention. We know that cabinet as a collective body is not a central decision-making mechanism and that the power of individual ministers has been eroded by the rise of prime ministerial and central agency offices, but we also know that cabinet committees have largely overtaken what role cabinet still plays. Thus, it is arguably much more important that regions are represented within cabinet committees than in the more publicly visible composition of cabinet generally. One of the few explicit claims made is James's (Reference James1999: 69) contention that, in comparison to the UK, “there is no requirement—unlike strongly federal countries like Canada—for committee memberships to reflect carefully the interests of different provinces.” However, no evidence is given for this claim. Mackie and Hogwood (Reference Mackie and Hogwood1984: 288–89) agree with this assertion, but Koerner (Reference Koerner1989: 12) suggests that Canadian cabinet committees “did not generally follow the principle of regional representation.” Indeed, he suggests that the absence of acceptable regional representation in the inner ministerial core was a factor in maintaining secrecy about committee membership.

The principle of regional representation in cabinet has not been shown to extend to influence within cabinet, particularly as reflected in the system of cabinet committees. Our goal is thus exploratory: there are reasons to be skeptical that region plays a strong role in the internal distribution of ministerial influence. First, it is structurally difficult for cabinet influence to be equitably distributed regionally, since all cabinets will have a hierarchy of more and less powerful ministers, to some degree, in which the former group is significantly smaller. Second, cabinet has a strong public-facing representational role that is aided by the flexibility of its size and composition. Prime ministers can, for example, increase the size of cabinet to ensure adequate provincial or regional representation or appoint particularly important regional figures to high-profile portfolios. Cabinet appointments generate significant media attention, in part because of the formal trappings they entail.Footnote 3 Cabinet committees, on the other hand, are almost invisible to the public, created with minimal fanfare and operating behind closed doors. They have little visibility as a representational mechanism. Thus, prime ministers are likely to feel much less pressure to consider region as important in shaping cabinet committees. Finally, because of the importance of committees to internal decision making and their use as mechanisms of policy coordination, other considerations, such as experience, trust and competence, are more likely to weigh highly compared to regional concerns. Thus, in assessing the role of region in cabinet committees, we also implicate the idea that regional representation in cabinet appointments is primarily symbolic and normative rather than a substantive way of empowering regional interests.

Therefore, this study assesses the question: What is the role of gender and region in a minister's structural influence within Canadian cabinet committees? I posit two main hypotheses. First, a minister's gender (binary-coded, with “female” the higher-coded value) should have a negative effect on ministerial influence, but this effect should be lessened in contexts of high supply of women in cabinet. In other words, female ministers are likely to have lower levels of influence within cabinet committees compared to male ministers. Second, ministers from “underrepresented” regions should be more likely to be influential than other ministers. While this second hypothesis is tested, a non-result would also not be surprising given the mitigating factors identified above. Simply put, I examine whether gender and regional representation inform decisions about cabinet committee structure and membership as they do cabinet appointment.

I also include other factors potentially related to ministerial influence, both as controls and for their inherent interest. Previous political experience, particularly ministerial, has been found to be important in cabinet selection in Canada (Kerby, Reference Kerby2009) and elsewhere (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2016). Theoretically, this has been framed in principal-agent terms: the prime minister as principal, using experience as a screening mechanism to minimize choosing agents who are not effective or trustworthy—the problem of adverse selection (Dowding and Dumont, Reference Dowding, Dumont, Dowding and Dumont.2015: 6–7; Strøm, Reference Strøm2000). The informational uncertainty that underlies adverse selection problems presumably decreases for potential ministers with prior experience; their competence and character are much more likely to be known. Therefore, I expect that previous ministerial experience will be positively associated with ministerial influence. This effect may be even more pronounced for cabinet committee influence than for ministerial appointment because of the relative inexperience of ministers and high legislative turnover in Canada (Kerby, Reference Kerby, Dowding and Dumont.2015: 272). Prime ministers are likely to be forced to appoint some ministers with little or no experience, but more influential positions can be reserved for those with experience. Notably, Kerby (Reference Kerby2009: 607) found a steep decline in the chances that a member of Parliament (MP) will be appointed to cabinet after their first term—indeed, after their first months in office. While not directly applicable to intra-cabinet influence, this suggests an expectation of a negative relationship between legislative experience and influence.

Second, the age of each minister at each change in cabinet committee structure was also collected. Both Kerby (Reference Kerby2009) and Fleischer and Seyfried (Reference Fleischer and Seyfried2015) examine the possibility that age is positively correlated with ministerial appointment, though the latter finds no significant effect. I examine this possibility again here, in the context of cabinet committee influence. Finally, I control for one contextual factor that has been examined in studies of gender and cabinet representation: the female share in the pool of potential candidates, typically measured as the percentage of women in the legislature (for example, Krook and O'Brien, Reference Krook and O'Brien2012; Curtin, Reference Curtin, Dowding and Dumont.2015). Krook and O'Brien (Reference Krook and O'Brien2012: 843–44) describe this effect as due to both the inherent supply of female candidates and the demand for representation increasing as more women occupy positions of political power and traditional gender norms break down. I apply this idea to the second-order arena of representation in cabinet influence. Just as having more women in legislatures tends to increase the likelihood of women being appointed to cabinets, having more women appointed to cabinet should increase the likelihood that women will be assigned greater influence within the structure of cabinet decision making, as reflected in cabinet committees.

Data and Methods

The dataset consists of all ministers assigned cabinet committee memberships in 10 distinct cabinet committee periods from 2003 to 2019. These periods were demarcated by materially significant changes in number or mandate; small changes in membership do not constitute distinct committee periods. This means that the data are not completely exhaustive of all ministers. Of the 10 periods, the first two were created under Paul Martin, the next five under Stephen Harper and the last three under Justin Trudeau, to March 2019. In total, there are 353 “minister-committee period” observations. Many ministers are included more than once because they served in multiple cabinet committee configurations. The period was chosen for both substantive and practical reasons. Substantively, covering three recent prime ministers—those most affected by evolving representational norms—was important. Practically, committee membership lists are not well documented online for periods before Paul Martin. While archival research has started to uncover prior lists (Everitt and Lewis, Reference Everitt, Lewis, Tremblay and Everitt2020: 203), they were not accessible by the author during the period of data collection.

For each minister-committee period observation, the following was collected or calculated. As predictors of influence, each minister's gender, age and federal legislative and ministerial experience, in years, at the start of the committee period, were obtained from Parlinfo (https://lop.parl.ca/sites/ParlInfo/default/en_CA/). The region (British Columbia, West, Ontario, Quebec, Atlantic Canada, North) of the minister's constituency was also collected. However, the salience of region is the idea that regions need to be represented regardless of, or in compensation for, actual regional distributions of caucus. Relatively small and less powerful regions such as Atlantic Canada need to be represented effectively in cabinet; regions that are underrepresented for political-electoral reasons—for example, the West for Justin Trudeau, or Quebec for Stephen Harper—also require consideration. This imperative is addressed first through cabinet selection, appointing ministers from all provinces or regions if possible. Kerby (Reference Kerby2009) measures this effect by including a regional seat share variable: the percentage of the government caucus from each MP's region. Thus, the predictor we employ is the regional share of cabinet positions. I expect this to have a negative effect on ministerial influence: the higher the share of cabinet positions for a region, the lower the influence, on average, a minister from that region should obtain. In additional models, I include the overall percentage of women in the ministry as an interaction with gender.

I measure ministerial influence outcomes quantitatively with three distinct but related measures. These are centrality, “coreness,” and share of committee influence. Centrality and coreness are network-based measures derived from mapping the structure of cabinet committees and committee membership as a social network. Network analysis is the study of structural relations among a set of actors (Knoke and Yang, Reference Knoke and Yang2008: 5). It has been used to study many political phenomena, including anti-government movements in civil conflicts (Metternich et al., Reference Metternich, Dorff, Gallop, Weschle and Ward2013) and party cohesion (Chartash et al., Reference Chartash, Caruana, Dickinson and Stephenson2020; for a review, see Ward et al., Reference Ward, Stovel and Sacks2011). Applying network analysis in the context of cabinet committees assumes that they can be theoretically conceived as networks, with membership of committees construed as “ties” between ministers. I also presuppose that locational network measures can be construed as reasonable proxies for ministerial influence. As Borgatti et al. (2018: 190) note, network measures are mathematical descriptions of network structure; they do not inherently mean anything other than the theoretical import provided by the analyst. If cabinet committee structures are reasonably conceived as networks, then a minister's position within the network, all else equal, is a strong indicator of importance and potential influence. As shown below, empirically these measures identify intuitively influential ministers reasonably well. Moreover, as the review above suggests, cabinet committees are important sites of policy making in Canada, and prime ministers use these choices strategically, not arbitrarily (see Ie, Reference Ie2019; Brodie, Reference Brodie2018). While not perfect, position within cabinet committee structure is one of the few objective, measurable manifestations of relative ministerial importance.

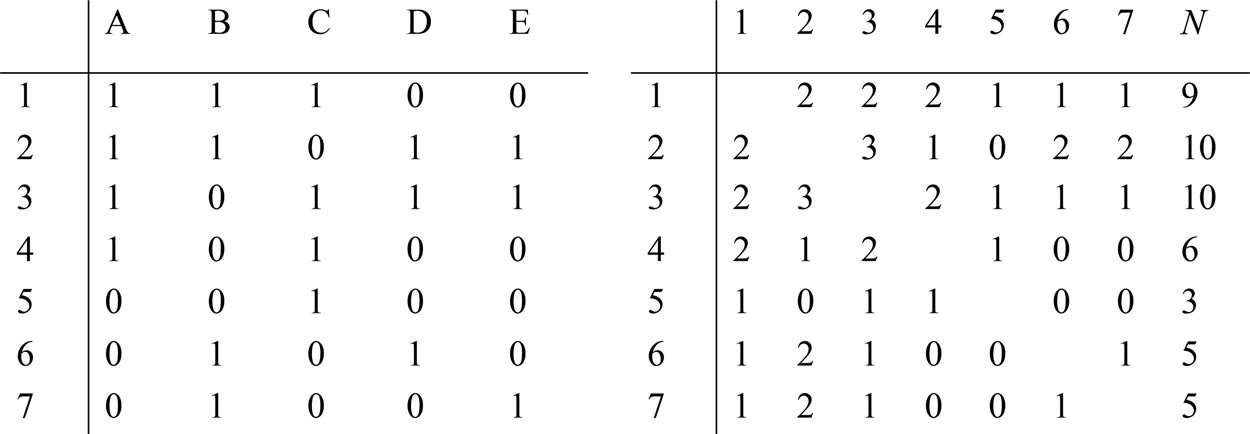

Centrality—specifically, degree centrality—is a measure of the number of ties a minister has to other ministers through shared committee membership, as a proportion of the total number of ties in the network.Footnote 4 Coreness is a measure of where each minister is located in the core-periphery structure of the network. A common conception of this structure in networks is that core nodes are well connected to other core nodes and peripheral nodes, while peripheral nodes are only connected to core nodes (Borgatti et al., Reference Borgatti, Everett and Johnson2018: 184). To illustrate, consider the committee system shown in Figure 1. On the left, an “affiliation matrix” shows membership of ministers one through seven on committees A through E. This matrix can be converted into an “adjacency matrix,” on the right. Entries are the number of committees on which the respective ministers both sit.

Figure 1 Affiliation and Adjacency Matrices, Committee Structure Example

Note: N = total number of ties.

For example, ministers three and four are co-members of two committees (A and C), while ministers five and seven are on none of the same committees. Minister three has a total of 10 ties of the 18, for a centrality score of 0.556 (10/18). Minister five, on the other hand, has a total of 3 ties for a centrality score of only 0.167 (3/18). The coreness measure is described in Borgatti and Everett (Reference Borgatti and Everett2000) and Borgatti et al. (Reference Borgatti, Everett and Johnson2018) and applied in, for example, Carboni and Ehrlich (Reference Carboni and Ehrlich2013) and Weeks et al. (Reference Weeks, Ksiazek and Lance Holbert2016). Briefly, the adjacency matrix is compared to an ideal matrix with blocks of strong ties between core nodes, weaker ties between core and periphery nodes, and no ties between periphery nodes (see Borgatti et al., Reference Borgatti, Everett and Johnson2018: 258). The values of the coreness for each node are those that maximize the correlation between the data matrix and the ideal matrix. Higher coreness scores indicate a greater likelihood of a node (a minister) being in the core (Carboni and Ehrlich, Reference Carboni and Ehrlich2013: 519). In the example, ministers one, two and three have high coreness scores (0.42, 0.55 and 0.53, respectively), while minister five has the lowest score, 0.13. The affiliation matrix in Figure 1 supports this; minister five sits on only one committee and would have a lower coreness score if that committee did not include ministers one and three. Overall, these scores fit the intuition that a minister who is more highly implicated in cabinet committee processes than a minister with more marginal interaction is more influential—or at least more potentially influential.

The third measure of ministerial influence is calculated only from each minister's membership on committees, not conceived as participation in a network. This share of committee influence measure follows Dunleavy's (Reference Dunleavy and Dunleavy1995) example. The measure quantifies the total influence available and each minister's share of the total. To construct it, I first weight committees by their importance. Ordinary policy committees are given a value of 1, while coordinating committees and those chaired by the prime minister are valued at 1.5. Then I apportion the committee value equally to each member, except that chairing a committee is counted as an additional membership, while vice-chairing is counted as half of an additional membership. We then sum these to obtain a measure of overall influence within cabinet committees for each minister and divide this total by the total influence available in each period to obtain a percentage share of influence (see Dunleavy, Reference Dunleavy and Dunleavy1995: 311).

Empirically, these measures accord reasonably well with outside observations of ministerial influence. For instance, in Trudeau's second cabinet committee period (2016–2018), the five ministers with the highest centrality are Jody Wilson-Raybould, Marc Garneau, Harjit Sajjan, Bardish Chagger and Dominic LeBlanc. The 2017 Hill Times list of the most powerful people in Ottawa place all except Chagger in the top 100, with Wilson-Raybould, Sajjan and LeBlanc in the top 25. Other powerful ministers such as Chrystia Freeland and Ralph Goodale are also relatively central. The most central Harper ministers include Jim Prentice, Lawrence Cannon, Denis Lebel, Jason Kenney and Rona Ambrose—all notably powerful figures—while the least central figures are almost entirely non-cabinet secretaries of state. The highest scoring ministers on each measure overall are identified in Table 1. Arguably, all identified ministers are either party stalwarts or rising figures at the time, which supports the prima facie validity of these measures. Nonetheless, some clearly influential figures, including finance ministers and even prime ministers, do not score highly on some or all measures. In Canada, it is not typical for prime ministers to sit on many cabinet committees, though they almost always chair the most powerful.Footnote 5 This underscores that the measures should not be interpreted as indicating overall influence or power within the decision-making process but only of structurally generated potential for influence within one executive decision-making arena. Other factors that give ministers influence—for example, importance of portfolio, departmental resources, personal closeness to the prime minister, expertise and background—are not directly captured in these measures, though future work could consider these as attributes of network nodes and theorize their structure. Finally, it is important to recognize that Canadian prime ministers retain the right to intervene in or override committee decisions regardless of ministerial influence; this has been characterized as “governing by bolts of electricity” (Savoie, Reference Savoie1999). Ultimately, ministerial influence is subject to the discretion of a prime minister and the centre of government.

Table 1 Most Influential Cabinet Ministers in Cabinet Committee Structure, 2003–2019

Note: LM = Liberal under Paul Martin; LT = Liberal under Justin Trudeau; C = Conservative under Stephen Harper.

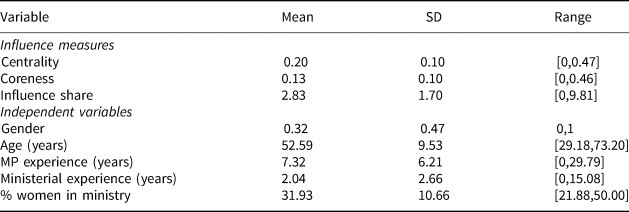

Summary statistics for all variables except region are displayed in Table 2. The mean for gender indicates that from 2003–2019, 32 per cent of the ministers on cabinet committees were female. This varies by prime minister, with Martin and Harper averaging about 25 per cent, while women constitute half of Trudeau's cabinets. The average age of ministers was 52.6 years. Both experience measures are right-skewed; in fact, almost 15 per cent of members had less than one year of federal legislative experience and over 50 per cent less than one year of ministerial experience. The skew did not result in heteroskedastic residuals, so no transformation was made.

Table 2 Variable Summary Statistics

Note: N = 353 for all variables.

For the dependent variables measuring ministerial influence, while degree centrality theoretically ranges from 0 to 1, the observed mean is 0.2, indicating that, on average, ministers have one-fifth of the total ties to other ministers through shared committee membership; no minister has a centrality score higher than 0.47. The core mean is 0.13 and is also right-skewed, indicating that coreness tends to be low with few high scores. While not the purpose of this analysis, this suggests that Canadian cabinets tend to have relatively strong core-periphery structures rather than more equally distributed influence. Finally, the mean of influence share, 2.83, indicates that the average minister obtains almost 3 per cent of the total available influence; even the highest score of 9.83 per cent, obtained by Prentice, may seem low. This is an artifact of the way the measure is calculated and an indication that Canadian cabinets are large, with positions distributed broadly. Even core ministers do not obtain high influence shares in absolute terms, so the measure is best understood as a relative indicator of ministerial importance.

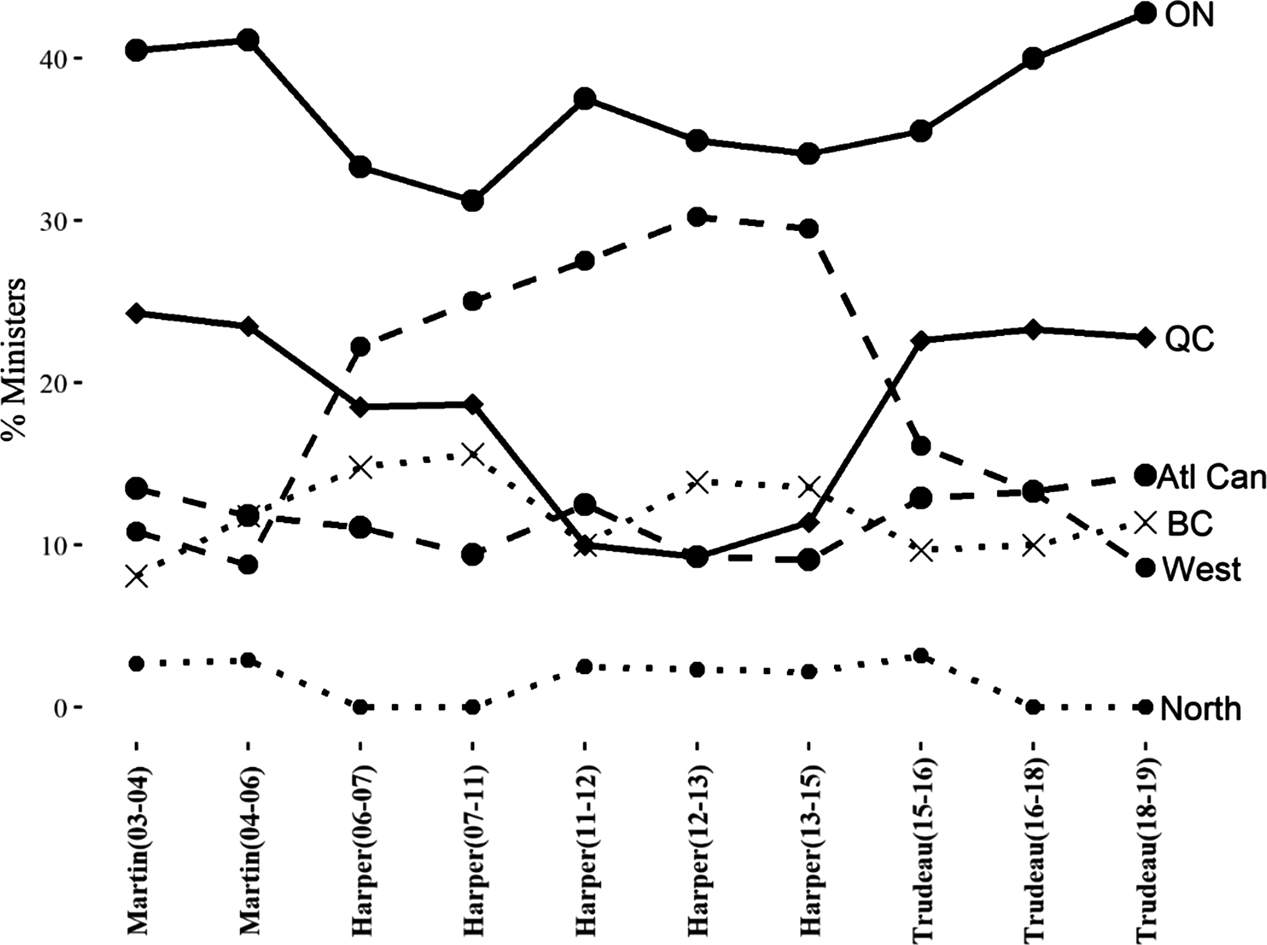

Figure 2 displays the percentage of ministers from each region for the 10 committee periods. Not surprisingly, Ontario, as the largest province, obtains the highest proportion of ministers in all periods. Under Stephen Harper, Ontario ministers constitute 34 per cent of the cabinet, on average, while they constitute almost 40 per cent of cabinet under the two Liberal prime ministers. In fact, the regional representational principle creates under representation of Ontario: under Martin, the province's share of the caucus is 55 per cent (post-2004); under Harper, it averages 37 per cent; and under Trudeau, 43 per cent. While the Ontario ministerial share is roughly consistent over time, both the West and Quebec ministerial contingents vary significantly. The West achieves near parity with Ontario in Harper's tenure, particularly during the Conservative majority government (2011–2015), but Western representation is under 10 per cent for the 2018–2019 period under Trudeau.Footnote 6 Conversely, Quebec ministers constitute almost one-quarter of cabinet under Martin and Trudeau but only 13 per cent under Harper. British Columbia and Atlantic Canada's cabinet representation, while varying, is not markedly different over time or as a function of prime minister or party. Of course, the single best explanation of these patterns is differences in the composition of government caucuses. When in government, both parties have received relatively strong caucus representation in Ontario, while the importance of the contribution of Quebec and the West to the government caucus alternates by party.Footnote 7

Figure 2 Regional Representation in Cabinet, by Committee Period, 2003–2019

Note: “West” includes Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. “Atl Can” includes New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

I assume a multilevel modelling framework to infer representational effects on ministerial influence because the observations at the minister level are embedded or clustered within cabinet committee periods. A minister's influence in one period may depend on the period-level distribution of influence. Additionally, many ministers are “measured” for more than one period. These issues suggest that the assumption of error independence may be violated. Statistically, a multilevel model is appropriate when the ratio of the between-group (here, between committee periods) variance to total variance is sufficiently large. This measure is called the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC, denoted by ρ), which ranges from 0, when none of the outcome variance is due to between-group differences, to 1, when the outcome variance is entirely due to such differences. Two of the three outcomes result in significant ICCs (centrality: ρ = 0.20; influence share: ρ = 0.04), while the coreness measure does not (ρ = 2.63e-10). A second method for assessing the need for a multilevel model is a likelihood ratio (chi-square) test between two models: the pooled (non-clustered) model and the multilevel model. This test identifies the same two models as requiring multilevel structure (centrality: χ2 = 52.7, p = .00; influence share: χ2 = 4.87, p = .03) and the coreness model as not (χ2 = 0, p = .99). Thus, the centrality and influence-share models include a random intercept for committee period, while the coreness model includes only fixed effects.

Results

This section presents results from estimating regression models of ministerial influence and evidence for the study's hypotheses. After testing the sufficiency of various model specifications, the final centrality and influence-share models employ fixed effects for gender, regional representation, legislator age, and parliamentary and ministerial experience, and a random committee period effect; all fixed effects except gender and all outcome variables were standardized. In particular, I tested for a random effect for gender, but likelihood ratio tests showed no significant improvement to model fit compared to a fixed effect (centrality: χ2 = 0.44, p = .80; coreness: χ2 = 1.45, p = .69; influence share: χ2 = 2.40, p = .30). I also examined and rejected the possibility of an additional clustering effect at the prime minister level. The mixed effects models for centrality and influence share were estimated using restricted maximum-likelihood with the lme4 package in R. The coreness model is estimated using ordinary least squares. The sufficiency of the final model specifications was validated after testing for violations of regression assumptions; these tests are available upon request.

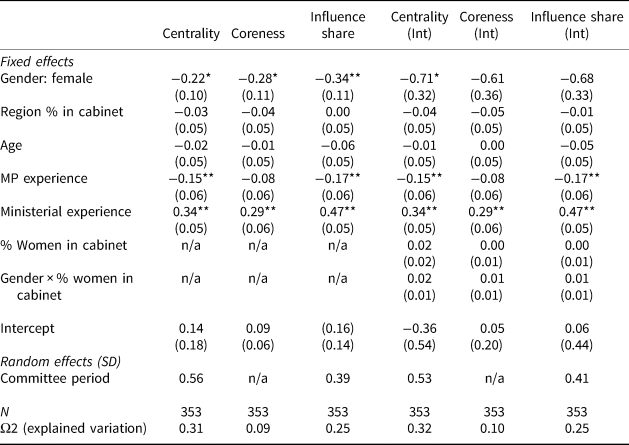

The results of the three main models of ministerial influence within cabinet committees are displayed in Table 3, along with models including an interaction between gender and the female share of cabinet positions variable. Goodness of fit of the models is indicated by the Ω2, a measure of explained variation appropriate for mixed effects models, as described in Xu (Reference Xu2003); the value for the coreness model is identical to the typical r-squared from an ordinary least squares model with fixed effects. The centrality and influence models explain a reasonable share of the variation in outcomes given their relative parsimony, at 0.31 and 0.25, respectively. The coreness model only explains about one-tenth of the variation: relatively low but not problematic given our goal is not prediction or forecasting. The random effect estimates indicate how much the intercept varies as a function of committee period, expressed in standard deviations of the outcome measures: 0.56 for the centrality model and 0.39 for the influence-share model. This between-period variation is difficult to interpret in the absence of comparable models but does suggest important differences in how these prime ministers have distributed influence among ministers, an argument explored in Ie (Reference Ie2019).

Table 3 Effects of Gender and Region on Ministerial Influence in Cabinet Committees

Note: Centrality and influence-share models have fixed effects for gender, region, MP and ministerial experience, and female cabinet share, with a random intercept by committee period. The coreness model is a fixed effects model. Fixed effects are standardized except for gender, which is a binary variable.

Entries are standardized coefficients with standard errors in parentheses.

* p < .05; ** p < .01

Our first main hypothesis states that gender will have a negative effect on ministerial influence, with female coded as 1, male as 0. The estimates indicate negative gender effects that are statistically significant at the .05 level, strongly supporting this hypothesis. On all three measures of ministerial influence, female ministers are less likely to be influential within cabinet committees than their male counterparts. In substantive terms, female ministers are estimated to obtain centrality scores almost one-quarter of a standard deviation less than male ministers, more than one-quarter of a standard deviation lower likelihood of being a core minister, and more than one-third of a standard deviation lower share of the total influence available. These effect sizes are visualized in Figure 3 on the original, unstandardized outcome scales. While not drastically large effect sizes, they are comparable to the effects of ministerial experience, which intuitively should be one of the strongest correlates of ministerial influence. These results clearly demonstrate that gender parity within cabinet committee structure is not evident, at least in this data and time period. Female ministers, on average, are less centrally located within cabinet committee structures, are less likely to be part of an inner core of most important ministers and obtain less overall share of influence on cabinet committees. These findings are in line with earlier findings that despite promising increases in descriptive representation in parliamentary executives overall, the gender gap in influence within executive decision-making processes remains.

Figure 3 Marginal Effects of Gender, Legislative and Ministerial Experience on Cabinet Committee Influence

We hypothesized that ministers from less-represented regions would, on average, be more influential than ministers from more represented regions. However, we were ambivalent about finding empirical support for this hypothesis because of the relative dearth of empirical validation that regional representation runs deeper than ministerial appointment itself. The results bear out this skepticism; there is no statistically significant effect of a minister representing a less-represented region on their likelihood of influence within cabinet committees. We confirmed this finding in alternative models with different constructions of the region variable. First, we ran models with a dummy variable for specific regions by committee period / prime minister: West, for Martin and Trudeau periods; Quebec, for Harper periods. Second, we constructed a variable of the ratio between regional share of cabinet positions and regional share of the total population, where values higher than 1 indicate a region that is overrepresented in cabinet relative to population share and values lower than 1 indicate an underrepresented region. Neither alternative regional variable is statistically significant; all other coefficients remained substantively similar in direction, strength and significance.

Experience as an MP has a statistically significant effect in two of three models, as shown in Table 2. The effects of experience as an MP are negatively signed though not very large, indicating that, on average, the more parliamentary experience one has, the fewer connections and lower influence share within cabinet committees one has. This result was expected but merits further explanation. The period under study includes two incoming governments—the Conservatives in 2006 and the Liberals in 2015—with a large proportion of MPs with no parliamentary experience. The Canadian House of Commons is characterized by a high level of MP turnover (Docherty, Reference Docherty1997: 41–42), particularly after a long-serving government is defeated and replaced by a party out of power for several cycles. In 2006, the cabinet of the new Conservative government included 7 of 27 members with no parliamentary experience (26 per cent), and 7 others had less than two years’ experience: more than half of the cabinet had little to no experience. In 2015, almost 60 per cent of Trudeau's cabinet had no parliamentary experience. Thus, the predominant share of ministers will be at the low end of experience and dispersed on the dependent variable, allowing the effects to largely be driven by those with high experience (that is, data points with high leverage). Since the estimate is of the independent effect of parliamentary experience, controlling for ministerial experience, it may be driven by a few ministers who are relatively long-serving legislators but are ministerial neophytes. As mentioned, Kerby (Reference Kerby2009) finds that an MP's likelihood of ministerial appointment declines rapidly after entering office; conversely, any new MPs seen as potentially strong ministers are likely to be appointed very quickly. This suggests that the few long-serving MPs who are appointed are not likely to be especially important or influential and may be appointed more for patronage or personal reasons. However, ministerial experience is estimated to have a positive, statistically significant effect in all three models. This indicates that, independent of legislative experience, ministerial experience is expected to increase the influence of a minister within cabinet committees. This is also driven by the high-experience ministers. Indeed, the data show that all ministers with high ministerial experience are relatively influential—some, like Ralph Goodale and Anne McLellan, are among the most influential—but several ministers with high legislative experience but low ministerial experience are among the least influential by these measures.

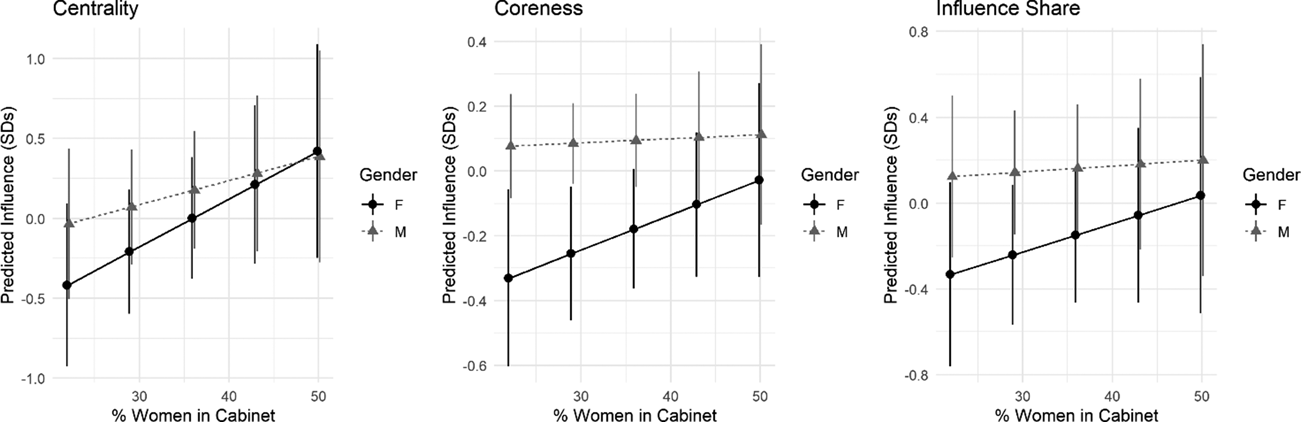

I also examined the possibility of interactions between gender and the overall percentage of women in cabinet to investigate the supply explanation for women's appointments to cabinet. Recall, this is the argument that more women are likely to be appointed to cabinet as more women are elected to the legislature. Our analogous hypothesis is that as more women are appointed to cabinet, the previously found negative effect of gender on influence will trend in the positive direction. The results of estimating this effect in models including other determinants of influence are given in Table 3 and visualized in Figure 4. The models indicate that there is no statistically significant effect on the interaction of gender with the percentage of women in cabinet; in other words, the effect of gender on ministerial influence does not significantly change as the percentage of women in cabinet increases.

Figure 4 Effects of Interaction between Gender and Percentage of Women in Cabinet

However, Figure 4 suggests a somewhat more complicated picture. The finding of no significance is driven by the high error variance in the estimates, shown by the overlapping of the vertical bars. In fact, comparing the slopes of the fit lines between “male” and “female” shows that in all three models, the negative effect is trending in the positive direction: the “female” slope is larger than the “male” slope, and the gap in estimated influence narrows as a function of the supply of women in cabinet, on average. For example, at the minimum share of women in cabinet, 22 per cent, the average estimated centrality of a female minister is −0.42, almost 0.3 SDs lower than the male estimate; at the maximum share, 50 per cent, the average female minister centrality is actually higher than the average male minister (0.42 vs. 0.39). Thus, while the analysis does not allow us to statistically conclude that the supply hypothesis is supported, a promising picture can be drawn: when more women are appointed to cabinet, it appears that, on average, women obtain more influence within cabinet committee structure.

Discussion and Conclusion

This article examines cabinet committees as sites of representation in Canada. It is the first study to rigorously assess representational characteristics within the internal decision-making processes of cabinet in Canada. While attention has been paid to gender and region as factors in ministerial selection, their role in intra-cabinet structures of influence has not been investigated. Arguably, this arena is even more important to questions of representation of social diversity than legislative or ministerial representation in parliamentary democracies such as Canada that have strong executive dominance (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012).

Using a dataset of cabinet ministers and cabinet committee structures from 2003 to 2019, under the last three prime ministers, I confirmed our main hypotheses that, all else equal, female ministers are likely to have fewer ties to other ministers; are less likely to be in the core of most important ministers; and likely to have a lower share of overall committee influence, as measured by membership on many committees and/or the most powerful committees. Simply put, in terms of structurally induced influence within cabinet decision making, equitable women's representation in Canada is far from realized. However, the data also suggest, though not conclusively, that more recent cabinets have improved in this regard. While the interaction of a minister's gender with the percentage of the cabinet that is female was not statistically significant, there is a reasonably clear positive trend. Gender parity in cabinet in future, or lack thereof, will allow more robust conclusions on this front. As Annesley et al. (Reference Annesley, Beckwith and Franceschet2019) argue, the importance of agency in those who select ministers—namely, prime ministers in Canada—will be crucial to the directions that women's representation in cabinet will take.

Region has long been a crucial consideration in cabinet selection in Canada. The significance of region, however, seems not to extend to the distribution of influence within cabinet committees. Ministers from regions with lower shares of cabinet representation are no more likely to be influential than regions with higher shares. This supports the conclusion of weak intrastate federalism in the form of powerful regional representation within cabinet (Everitt and Lewis, Reference Everitt, Lewis, Tremblay and Everitt2020: 196). The representational imperative for regional balance is seemingly more a matter of adherence to norms and “token” representation than meaningful empowerment of regional interests at the federal level. While not primary variables of interest, age and legislative and ministerial experience were also included in the models of ministerial influence. Age was not a statistically significant contributor to influence in any models, but experience of both types was. Interestingly, legislative experience was negatively associated with influence, but ministerial experience was positively associated.

This study argues for the importance of considering cabinet committees as sites of representation and offers a novel methodological approach and new empirical insights to the literature on representation of diversity. The analysis readily extends to the study of other parliamentary cabinets, both internationally and subnationally in Canada. Examining alternatives for measuring ministerial influence would also be fruitful. Representations of social diversity should be considered key dimensions within a central arena for executive decision making such as cabinet committees; as Annesley and Gains (Reference Annesley and Gains2010) have noted, there is a significant gendered component to the opportunity structures and access to influence within the core executive. This research calls attention to that goal.