‘British rhythm-and-blues may sound as anomalous as British sherry’, opined prominent English jazz critic Philip Larkin in December 1962 (Larkin Reference Larkin1985, p. 77).Footnote 1 It was with these words that Larkin opened his review of the recently released LP, R&B from the Marquee, by the London-based Alexis Korner's Blues Incorporated. A commentary about national proclivities and capacities, this statement laid bare a commonly held belief in the UK at the time: in order for a record to bear the designation ‘rhythm and blues’, it necessarily had to be the product of African Americans – preferably those who resided and recorded in Chicago. Whether British musicians authentically could or properly should perform in rhythm and blues styles was a superfluous (if common) discussion.Footnote 2 The fact was that British musicians were playing what they referred to as R&B, and in ever-increasing numbers. Although Larkin notes that Korner had amassed a ‘large following’, his review proceeds to express his own relative surprise and ambivalence about R&B from the Marquee. Toward this end, he refers to the songs on the album as ‘hearty derivatives. … The singing is not always on pitch, but Cyril Davie's [sic] harmonica and Korner's electric guitar blow up a fine storm if you like this flamboyant Negro mode’ (Larkin Reference Larkin1985, p. 77). What Larkin could not have predicted at the time was that less than two years later, quite a few among the British masses would develop a taste for just such ‘flamboyant derivatives’ in the ‘Negro mode’ and that rhythm and blues as performed by white Britons would be about as ubiquitous in and seemingly indigenous to England as London dry gin.

The ‘large following’ Larkin mentions in his review was still relatively modest in the last months of 1962, but was nonetheless indicative of a nascent London rhythm and blues scene. Over the course of 1963, rhythm and blues would usurp trad jazz as the sound of choice in London's clubs and, by the end of the year, infiltrated Britain's television programmes and pop charts. In 1964, British R&B, led by the Rolling Stones, Manfred Mann, the Animals, the Yardbirds, Dusty Springfield and a host of other African-American-inspired acts, came to dominate the UK mainstream and would, in turn, function as a central element in the ‘British Invasion’ of the US pop charts.

In retrospective accounts, Blues Incorporated's R&B from the Marquee – both the album and the live performances the record was meant to recreate – is often credited as the original British expression of rhythm and blues. Tony Bacon's chapter on British R&B in London Live provides a typical version of Blues Incorporated's origin story:

[Chris Barber's] biggest coup came in presenting Muddy Waters in October 1958 … Korner persuaded Muddy Waters to drop by the Roundhouse [home of Korner's Barrelhouse & Blues club], and the American cheerfully blasted out some beer-glass-rattling R&B on his telecaster. Korner, spurred on by these first-hand experiences, was invited by Barber toward the end of 1961 to rejoin the Barber band for another ‘interval act’; not this time playing skiffle, but electric blues. Korner also resolved to put together his own group, Blues Incorporated. (Bacon Reference Bacon1999, p. 46)Footnote 3

Scholars like Roberta Freund Schwartz have offered that ‘Blues Incorporated was a nursery for the first generation of British blues and R&B artists’ (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2007, p. 128).Footnote 4 Bob Brunning's Blues in Britain opens with a chapter titled ‘Roots – Alexis, Cyril and the Stones’ that similarly celebrates Blues Incorporated's 1962 performances as the earliest attempt at rhythm and blues in the country (Brunning Reference Brunning1995, pp. 12–14), as do any number of accounts in the secondary literature, textbooks and reference works (in scholarship see Adelt Reference Adelt2010, pp. 59–60; Kellett Reference Kellett2008; in textbooks see Covach Reference Covach2009, pp. 174–5; Garafalo and Waksman Reference Garafalo and Waksman2014, p. 167; Szatmary Reference Szatmary2014, p. 121). This narrative extends to discographies of the period as well, as evidenced by Leslie Fancourt's British Blues on Record 1957–1970, in which the only entries for the years 1957–1962 are records by Korner (Fancourt Reference Fancourt1992). This type of curation insinuates that these are the only legitimate predecessors to the December 1962 release of R&B from the Marquee. It should be noted that such assessments are not entirely unjustified. By all accounts, Blues Incorporated was the first dedicated R&B band in the UK and their performances inspired other like-minded musicians – members of the Rolling Stones, Manfred Mann, Ginger Baker, Jack Bruce – to follow suit. The concern of this article, however, is what uncritical overreliance on this narrative leaves out.

Almost entirely omitted from these narratives are the women musicians and fans who participated in this story. Particularly notable in her absence is Ottilie Patterson, Britain's most popular and accomplished blues singer of the second half of the 1950s and the early 1960s. In histories of British blues it is rarely acknowledged that, when Muddy Waters took the stage in Britain on his 1958 tour, he shared a microphone with Patterson.Footnote 5 Absent is the fact that it was Patterson, not Korner, who was the first to perform, much less record, rhythm and blues in Britain and that it was only following Korner's experiences backing Ottilie Patterson's R&B interval sets at the Marquee in mid-1961 that he turned his attention to performing rhythm and blues.Footnote 6

Based in part on Ottilie Patterson's elision from the historical record, academic and popular histories alike typically describe British R&B as stemming first and foremost from the actions of young, white, middle-class British men who turned to the sounds of black American men for musical motivation. Many scholars relying on this narrative have argued that this articulation to the blues – particularly the ‘down-home’ blues of Mississippi circa 1930 and of early 1950s’ Chicago – by white male Britons represented a desire to identify with and vicariously embody a romanticized representation of black masculinity.Footnote 7 In this vein, Simon Frith and Howard Horne suggest that from ‘rhythm club to rhythm and blues’, interest in black sound was primarily a masculine enterprise, noting that ‘for most young white performers the ‘realism’ of blues was contrasted to the ‘soppiness’ of teen pop in terms of a masculine vs. feminine sensibility’ (Frith and Horne Reference Frith and Horne1987, p. 92). Building on these observations, Susan McClary, contends that,

it is significant that it was the music of black males that they idolized, for African Americans were thought to have access to real (i.e. preindustrialized) feelings and community – qualities hard to find in a society that had so long stressed individuality and the mind/body split. Moreover, in contrast to what politicized art students regarded as the feminized sentimentality of pop music, blues seemed to offer an experience of sexuality that was unambiguously masculine (McClary Reference McClary2001, p. 53).

Andrew Kellett, in his chapter ‘But my dad was black: Masculinity, modernity and blues culture in Britain’, discusses this imagined connection between African American bluesmen and British R&Bers at length, concluding that for

young white men who felt that either their masculinity, or their ability to express that masculinity, was in crisis … the [blues] idiom and its cultural trappings provided a blueprint (no pun intended) for an alternative masculine ideal to the normative bourgeois masculinity that the post-war period had re-inscribed. In the ‘bluesman’, who was himself a constructed artistic persona, the young Britisher found a ‘man-of-adventure’ whom they perceived as skilled, self-assured, and sexually dynamic (Kellett Reference Kellett2008, p. 229).Footnote 8

More than two years prior to the release of R&B from the Marquee a woman entered the studio to record a ‘tour-de-force on a range of blues and rhythm-and-blues’, the likes of which had not been attempted in the UK prior (Melody Maker, 10 June 1961, p. 3). Ottilie Patterson's July 1960 ‘tour-de-force’ recording sessions resulted in the rather ostentatiously titled Chris Barber's Blues Book, Volume 1: Rhythm and Blues with Ottilie Patterson and Chris Barber's Jazz Band (Columbia, 33SX 1333, released July 1961, hereafter ‘R&B with Ottilie’). Despite the fact that it substantially predates the Blues Incorporated record, historians of British blues are either unaware of or have broadly ignored R&B with Ottilie in favour of Korner's effort. In the rare instance when it is mentioned at all, descriptions of the album are brief and typically misinformed.Footnote 9 Contrary to conventional historical claims, this album was the first recording of British musicians bearing the designation ‘rhythm and blues’ and it is this album that represents the first concerted effort to revive American R&B in the British setting.

Here, I offer a revision to the dominant historical narrative of British R&B by reinserting Ottilie Patterson. Rhythm and Blues with Ottilie Patterson, in particular, allows for such a reappraisal. Analysis of Patterson's performances captured on this record – original blues compositions and reworkings of existing blues lyrics alike – demonstrate how R&B was first publicly (re-)presented and understood from within the British trad jazz/blues/R&B revivalist world – not only from a female singer, but from a woman's perspective.Footnote 10 In addition to a close examination of musical excerpts from R&B with Ottilie, this analysis draws upon Patterson's notebooks held at Britain's National Jazz Archive. The reflections, lyric sheets and performance notes contained within these notebooks provide a personal perspective on R&B in Britain from a fan who consumed the music and a musician who played an active role in shaping perceptions about the genre.

‘Britain's number one blues singer’

Ottilie Patterson's interest in the blues began as a student at the Belfast College of Art. A notebook Patterson maintained between 1951 and 1952 reveals that a record-collecting fellow student introduced her to the sounds – and associated mythology – of the music. Patterson's early exposure thus followed a collector-oriented, peer-mentorship model which was common within art school circles in the 1950s and 1960s and remained a central pillar of informal popular music education in the second half of the twentieth century.Footnote 11 Under the heading ‘How Derek (Haggis) Martin introduced me to Jazz – 1950’, Patterson affixed four sheets of annotations that most likely accompanied records Martin lent her. The first of these reference Jelly Roll Morton's ‘Oh Didn't He Ramble’ and ‘Winin’ Boy Blues’ (which Martin mislabels as ‘Whinin’ Boy Blues’). In his note, Martin provides Patterson with ‘historical’ context for the recordings, letting her know that ‘Jelly Roll Morton was an old Negro pianist who spent most of his life in jail or in brothels’. The reproduction of another one of these annotations in Figure 1 is representative of these notes.

Figure 1. ‘Bessie's Disco’ annotation from the Ottilie Paterson Collection.Footnote 12

In another section of the notebook, Patterson transcribed the lyrics to eight early blues and jazz recordings, including four associated with Bessie Smith – ‘Backwater Blues’, ‘St. Louis Blues’, ‘Nobody Knows You When You are Down and Out’ and ‘Careless Love Blues’ – all written in an ornate calligraphic hand, utilizing initials (or drop caps) to group the a phrases in the typical aab blues lyric structure (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Ottilie Patterson's lyric transcription of ‘Backwater Blues’.

Patterson began publicly reproducing the sounds she heard on these records the following year with a group called the Jimmy Compton Band. Patterson's most formative early performance experience, however, came alongside Martin in a group that called themselves the Muskrat Ramblers. According to Patterson's ’51–52 notebook, the group debuted at the Ulster Rhythm Club on 26 August 1952. Although there are no extant set lists or recordings from Patterson's performances with the Muskat Ramblers, the lyric transcriptions contained in her notebooks indicate that she was almost exclusively performing blues numbers from the start of her career. After a few years earning a living as a schoolteacher and gigging on the side, a holiday visit to London during the summer of 1954 resulted in Patterson's elevation to the professional stage.

On 9 January 1955, Ottilie Patterson debuted as featured singer for Chris Barber's jazz band at London's Royal Festival Hall. Despite the all-star line-up of Britain's most accomplished traditional jazz bands and the presence of established British jazz singers Beryl Bryden and George Melly on the bill, it was Ottilie Patterson who was widely hailed as the highlight of the evening. Melly, perhaps the most popular British blues singer prior to Patterson's debut and one of the few male blues singers in the UK at that time, referred to Patterson as no less than a ‘phenomenon’, her performance that of ‘an authentic blues singer hard at work’ (Melly Reference Melly1955, p. 8). ‘Unknown blues singer triumphs at Festival Hall’, read the headline for the New Musical Express's 14 January 1955 review of the concert.

Although the other two numbers she performed that evening are lost to posterity, Patterson's rendition of ‘St. Louis Blues’ was captured on vinyl and released in April of that year on an LP collection titled The Traditional Jazz Scene (Decca, LK4100, 1955). Announced on the recording by Barber as ‘the oldest and perhaps most famous blues of all’, ‘St. Louis Blues’ was an apt introduction to a singer who would be so closely associated with the blues and Bessie Smith throughout her career. This association is all the more strongly reinforced as Patterson and the Barber band clearly emulate the Bessie Smith/Louis Armstrong 1925 recording of the song. The almost dirge-like tempo of the Patterson/Barber version is nearly identical to the Smith/Armstrong record and the limited backing of trumpet, trombone, banjo and bowed bass during the first two verses of the performance is employed in a manner evocative of the reed organ that accompanied Smith. Barber's responsorial phrases to Patterson's vocal lines in verses three and four are similarly reminiscent of the exchanges between Smith and Armstrong in the 1925 version. Such evocations of a recording so enshrined in the traditional jazz canon as the Smith/Armstrong ‘St. Louis Blues’ paired with Patterson's uncanny ability to match Bessie Smith's timbres and phrasing offer ample cause for the positive reception Patterson received.

While generally complimentary of the rest of the performances that evening, New Musical Express's praise of the newest addition to the British trad scene was unequivocal:

Fair-haired and rather frail looking … [Patterson] stopped the show with three numbers, sung with all the power and feeling of the great blues singers … The inclusion of Ottilie Patterson lifted [Chris Barber's portion of the concert] to the superlative. If you weren't at the concert and think I rave too much, go and hear this girl. (New Musical Express 1955)

From the point of her debut onward Patterson continually presented the British jazz world with a ‘descriptive problem’, as a November 1955 bio would so succinctly and eloquently state (2nd British Festival of Jazz Programme 1955, p. 13). Patterson was consistently referred to as ‘fair’ and ‘slim’ with the occasional ‘slight’ or ‘frail’ thrown in for good measure. This stood in stark juxtaposition to the literal and figurative larger-than-life image of the ‘red hot mama’ associated with Bessie Smith and other African-American women singers of the classic blues era. It was also in direct contrast with her British blues-singing contemporaries like Beryl Bryden, whose physique was reminiscent of the blues queens of the 1920s. The incongruity of her ‘slim’, ‘slight’ physical stature with the unquestionable depth and power of her voice were a repeating motif in just about any discussion of Patterson, not to mention the perceived incompatibility of being an Irish blues singer. In this regard Melody Maker dubbed her the ‘Ulster Enigma’ in its first dedicated profile of Patterson. ‘To look at her, you wouldn't take her for a blues singer’, the article explains, ‘but then, you wouldn't take any native of these islands for one – not if you were up on the story of jazz’ (Melody Maker, 26 March 1955, p. 2).

It was along this latter, racialized line of logic that much of the early criticism of Patterson was levied. ‘Yet another singer attempting to copy Bessie Smith’, a rather pointed letter to Melody Maker's editor suggested in the same issue as her first profile, ‘the forced voice, the fake American accent and the pathetic attempt to convince. Let's face it – only the Negro can sing the blues’ (Melody Maker, 26 March 1955, p. 6). The voice she sang in was ‘not her own’, so many critics claimed; she ‘gives the impression of a spiritualist, with the voices of singers long dead coming from her mouth. Ottilie must learn to project herself’ (Lindsay Reference Lindsay1955, p. 2). At work in these critiques of Patterson's abilities and aesthetic proclivities is a tension between the British desire to recreate and revive African American musical styles on the one hand, and a deep-seated concern about who could be considered qualified to do so.Footnote 13 Such critiques were often countered by reframing the authenticity debate. Sleeve notes for her EP Blues (Decca DFE 6303, 1956), for example, claimed that Patterson's singing ‘is proof that jazz can be universal music; it only needs deep love and understanding of the Negro and his music; there are no material grounds for supposing that Europeans are physically incapable of producing real jazz’. Despite the occasional critical ambivalence directed toward Patterson, she was widely acknowledged to have achieved a level of mastery over the blues idiom that few other British singers could claim, a mastery that led to the cover of the 8 February 1958 issue of Melody Maker to casually yet unequivocally dub Patterson ‘Britain's number one blues singer’.Footnote 14

Rhythm and blues with Ottilie Patterson

Referred to by Melody Maker as a ‘very credible Ottilie Patterson essay in the blues and allied song forms’ (Melody Maker, 8 July 1961, p. iv), R&B with Ottilie featured material ranging from the classic blues staples for which Patterson was previously known (Bessie Smith's ‘Backwater Blues’, 1927) to recent crossover R&B hits from Ruth Brown (‘Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean’, 1953); as well as a pair of newly composed blues tunes written by Patterson (see Table 1 for full track listing). These Patterson originals – ‘Bad Spell Blues’ and ‘Tell Me Why’ – number among the first blues verses penned and recorded by a British artist and are the first known to be written by a British woman.

Table 1 Rhythm and Blues with Ottilie Patterson track listingFootnote 15

*Debut recording on R&B with Ottilie.

As a Brian Rust review of the album suggests, absent from R&B with Ottilie are the ‘grinding tenor saxes and hollow-toned electric guitars’ that were ubiquitous in post-war R&B (Rust Reference Rust1961, p. 132). Instead Patterson is backed by a typical trad jazz line-up of drums, double bass, banjo, trumpet, trombone and clarinet. It is also notable that many of the songs on the album do not fit neatly into current-day generic understandings of 1950s’ [US] R&B. For many jazz enthusiasts in Britain at the time, however, ‘rhythm and blues’ was considered a continuation of what was once known as ‘race music’ rather than a specific instrumentation and set of stylistic conventions.

The term ‘R&B’ appears to have entered Britain's musical taxonomy through an influential October 1952 Jazz Journal article titled ‘Inside Rhythm and Blues’ penned by columnist and Vogue Records executive Doug Whitton (Whitton Reference Whitton1952). Published just three years after Billboard coined the term, ‘Inside Rhythm and Blues’ details the aural, social and cultural connections between African American styles of the 1920s–1940s and the rhythm and blues of the early 1950s. Underscoring this point, the article emphasizes that this latter style is but the latest iteration of records ‘produced for sale more or less exclusively in coloured areas, to coloured people’ (Whitton Reference Whitton1952, p. 1). Whitton mentions a diverse array of ‘new stars’ with ‘very real talent’, including Wynonie Harris, Eddie Vinson, Ruth Brown and Dinah Washington, as well as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and John Lee Hooker – the latter group contributing a ‘more primitive type’ of offering to the burgeoning field (Whitton Reference Whitton1952, pp. 1–2). Writing for the Melody Maker in January of 1954, Doug Whitton would again ‘put the spotlight on R. and B.’, noting that ‘like every other derivative of jazz, [R&B is] impossible to define precisely, but it may best be defined as the type of record which the present-day Negro population of the U.S. likes and buys … In the ‘thirties and ‘forties they would have been called “Race” records’ (Whitton Reference Whitton1954, p. 3). Later in the decade Paul Oliver defined ‘rhythm and blues’ as a rebranding of ‘race music’, a term that ‘hitherto described Negro folk musical forms’ (Oliver Reference Oliver1957). Versions of this broad notion of R&B held considerable sway well into the 1960s and appear to have informed its early British practitioners. Chris Barber noted that when he ‘began to do R&B numbers with Ott and the band’, circa 1959, they considered ‘R&B’ the ‘amalgamation of all the blues styles of the artists in Chicago who were active from the late Thirties onwards’ (Barber Reference Barber1963, p. 6). Following the release of R&B from the Marquee, Alexis Korner offered that R&B ‘covers everything in Negro popular music from Louis Jordan, through the various Buster Bennett groups, including the Muddy Waters field, right up to present-day American artists like Martha and the Vandellas, Marvin Gaye, and the Temptations’ (quoted in Coleman Reference Coleman1964, p. 7). This conception of R&B allowed for performance styles associated with Ruth Brown and Muddy Waters to appear on the same continuum, in the same broad category, and be contained on the same album as those by Big Maceo and perhaps even Bessie Smith. In its repertoire, R&B with Ottilie communicates this distinctly British revivalist vision of rhythm and blues in a way that reflects a sense of inclusivity in terms of period, style and gendered voices. While anachronistic to much of the source material the album draws upon, R&B with Ottilie's New Orleans jazz-style instrumentation throughout functions to further collapse the original stylistic differences into a more unified sounding of this conceptualization of ‘R&B’.

She got the blues

Lyric analysis has been a mainstay of blues scholarship at least since Paul Oliver published his influential The Blues Fell This Morning in Reference Oliver1960 and can be found in the work of traditional blues writers like Samuel Charters and Griel Marcus. A number of landmark feminist studies in the 1980s and 1990s from Hazel Carby, Angela Davis and others have likewise employed this practice in an effort to recuperate women's blues from the margins of popular music scholarship (Carby Reference Carby1986; Davis Reference Davis1998; Garon and Garon Reference Garon and Garon2014; Kernodle Reference Kernodle and Bernstein2004; Lieb Reference Lieb1981). Many of these, much like Oliver's work, employ the methodology of lyric analysis to illustrate the ‘collective feelings of the black community and … personal sentiments of the women performers’ expressed in these verses (Kernodle Reference Kernodle and Bernstein2004, p. 229). In other words, the analysis of lyrics has served numerous ends, ranging from Oliver's effort to discern the ‘meaning’ (and prescribing the boundaries) of the genre, to the construction of performer biographies (Marcus Reference Marcus1975), to more recent attempts to locate black (proto-) feminist attitudes in blues stanzas. Throughout, and especially in works like Davis's Blues Legacies and Black Feminism and Carby's ‘It jus be's dat way sometime’, distinctions have been made between the types of stances and themes common to women's and men's blues.

While lyric analysis has yielded important interventions, critics of this approach have contended that interpreting blues verse from a purely literary perspective elides the connotative power that the performance of these words communicates. The following analyses attend to the vocal performance, accompaniment and lyrics in Patterson's covers of songs originally performed by African-American women. Examination of these recordings reveal a consistency in Patterson's choice of representational positions and attitudes, positions she may have hoped to personify on R&B with Ottilie. Furthermore, these songs demonstrate how revivalist reproduction of extant lyrics – as well as performance practices – across historical and cultural lines creates the potential for different attitudes and subject positions to be expressed through the same or similar verses. It is remarkable that, with the exception of Ruth Brown's ‘Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean’, each of the six women's blues covers on R&B with Ottilie were composed by the song's original, female performer. It seems something of a coincidence that Patterson overwhelmingly selected tunes – e.g ‘Trixie's Blues’ and ‘R.B. Blues’ – that were so thoroughly entangled with these singer's identities.

Amongst the scrapbooks, photos and programmes contained in the Ottilie Patterson Collection at Britain's National Jazz Archive is a notebook containing lyrics, poems, notes and the occasional personal reflection. Although many of the pages had been removed before the notebook was deposited in the Archive (possibly by Patterson as she worked in the notebook, perhaps later), more than half of what remains comprises transcriptions of existing blues lyrics, drafts of original lyrics, notes about performance/arrangements and song lists. The opening page, for example, contains Patterson's transcription of the lyrics to ‘It's All Over (R.B. Blues)’, while the final page of the notebook contains a list of 14 songs arranged in what could be the layout of a tracklist for an album (see Figure 3). Ten of 14 songs in this list appear on R&B with Ottilie. Footnote 16

Figure 3. Potential track listing for R&B with Ottilie.

This notebook's contents suggest that Patterson maintained it in the lead-up to and during the recording of R&B with Ottilie. Within the pages of this document, traces of the development of the album's concept, scope and, eventually, near-final form can be read. While the following analyses primarily focus on Patterson's recordings themselves, I also draw on this notebook for the clues it provides about her artistic process, musical arrangements and lyrical inspiration.

‘Me and My Chauffeur’

Of the blueswomen known to British audiences, Memphis Minnie was one of the few that did not easily fit into the established, contemporaneously circulating models of ‘classic blues queen’ or ‘big band thrush’. As a singer and guitarist performing in a rural-inflected ‘city blues’ style during the 1930s and 1940s, Minnie embodied a representational ambiguity. Hers was a blues delivered from a woman's perspective, but through the generic conventions of an overwhelmingly masculine form. As Paul and Beth Garon note:

Minnie undermines the male standard of the country blues by the subversion and opposition inherent in her role … she challenged and weakened the patriarchal notion that blues women should sing on stage with male orchestral accompaniment. Her guitar proficiency … so completely upset the patriarchal apple cart that her admirers continually described her, with awe, as playing ‘as good as any man’. (Garon and Garon Reference Garon and Garon2014, p. 144)

Minnie's lack of conformity to traditional, gendered positions and representations extended to her lyrics as well. For these reasons, Minnie has widely been regarded by blues aficionados and scholars alike as a ‘female potentate in a man's world’ (Garon and Garon Reference Garon and Garon2014, p. 13). In his well-circulated Big Bill's Blues, Big Bill Broonzy discusses Minnie's musical abilities, noting that she bested both himself and Muddy Waters in ‘cutting contests’ on separate occasions (Broonzy Reference Broonzy and Bruynoghe1955, pp. 104–6). It is quite likely that Ottilie Patterson would have been aware of Memphis Minnie's reputation. Patterson would have, at the very least, had access to Minnie's most popular sides, ‘Me and My Chauffeur’ and its B-side ‘Can't Afford to Loose My Man’.

Originally written and recorded by Memphis Minnie in 1941, ‘Me and My Chauffeur’ is a witty, hokum-esque, double-entendre-laden lyric about a woman wanting to buy her chauffeur a ‘brand new automobile’ so that she can let him ‘drive me around the world’. ‘I want him to drive me down town’, she implores, ‘for he drives me so easy, I can't turn him down’. In addition to praise for her chauffeur, Minnie also offers him some counsel. If she were to catch him ‘riding his girls around’, she notes, she'd ‘steal a pistol’ and ‘shoot [him] down’. The protagonist of this song, thus, is a woman with the desire, if not the means as well, to purchase new cars and hire a driver. Furthermore, she also possesses sexual desires and is not afraid to express them. Such an expression of sexual desire through double entendre was widespread in most pre-war blues-oriented genres, by men and women alike. The evocation of sexuality in women's blues, however, as Hazel Carby, Michelle Wallace and others have noted, stood as a means to shift black women from ‘sexual objects’ to ‘sexual subjects’ (Wallace quoted in Garon and Garon Reference Garon and Garon2014, p. 151). ‘Me and My Chauffeur’ further asserts female sexual subjectivity by positioning the chauffeur and his ‘brand new automobile’ as the objects to be desired.

Unlike the other 11 tracks on the album, Patterson is backed only by a rhythm section on ‘Me and My Chauffeur’ without frontline horns. In addition, the rhythm section's performance is uncharacteristically restrained. While the bass walks steadily and the drum part is relatively active (although played with brushes), the banjo's quarter-note comping is all but inaudible. Four turns through a 17-bar blues form and all of 1:29 seconds long, the focus of the recording remains squarely on Patterson's vocal throughout, allowing her voice to dictate the terms of this arrangement.Footnote 17 Patterson even fills in the final bars of each chorus with a self-responsorial vocal tag – in place of the more typical instrumental turnaround – while the bass and banjo remain squarely on the tonic chord, ceding this harmonic and melodic space to Patterson's vocal embellishments.

Patterson's performance of ‘Me and My Chauffeur’ is dynamic and aggressive, delivered in a manner that suggests she is striving to embody the attitude projected by the lyric. Patterson's singing here is primarily declarative and syllabic with the occasional two- or three-note prolongation added to certain words. In particular, she applies prolongations to words that demand extra emphasis to convey meaning within the double-entendre setting; ‘dr-ive me do-own-town, well he drives me so easy I can't turn him do-wn’ and ‘I want to buy him a brand new a-u-o-to-mo-bi-ile’ for example. Moreover, her textual interpolations, what I referred to above as self-responsorial vocal tags, at the end of verses one and two – ‘whoa, oh no’, in response to ‘I can't turn him down’; ‘oh yes I would’ following ‘I'd shoot my baby down’ – reinforce the song's tenor while serving to further align Patterson's vocal with the conventions of black women's performance practice. These affirmations further cast Patterson as the sexual subject of ‘Me and My Chauffeur’ rather than the song's object while expressing the apparent joy the position provides her.

‘R.B. Blues’

Even before a single side of her music was released in the UK, Ruth Brown was the subject of the nascent R&B discourse in Britain. In an April 1953 piece for Melody Maker, Ernest Borneman noted the US crossover success of Brown's ‘Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean’ as a ‘breaking down of racial barriers’ in the American music scene (Borneman Reference Borneman1953, p. 4). Melody Maker would again mention ‘Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean’ on 19 December when it reported that Down Beat voters selected the song as the ‘R&B record of the year’ for 1953. In 1955, the London-American label reissued a number of Ruth Brown records for the first time, including an EP titled The Queen of Rhythm and Blues. Three of the first five songs transcribed in Patterson's R&B with Ottilie notebook are Ruth Brown numbers found on these releases: ‘R.B. Blues (renamed ‘It's All Over’ here)’, ‘Mama’ and ‘As Long as I am Moving’. She would record versions of ‘It's All Over’ and ‘Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean’ for R&B with Ottilie.

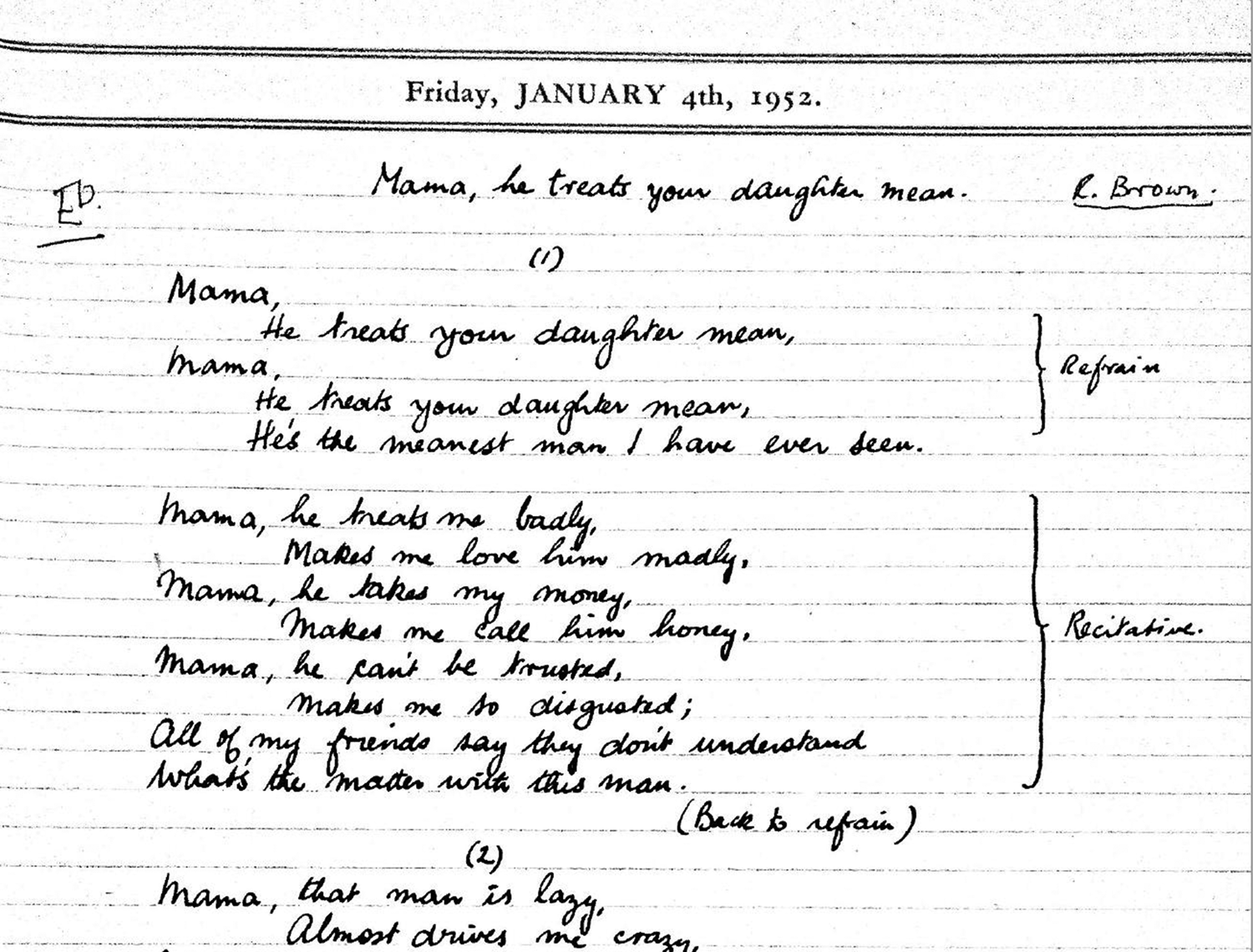

These two tracks both address mistreatment by a lover, a particularly common theme within the women's blues oeuvre. ‘It's All Over’, one of the few songs Brown composed, speaks of a woman's feelings of relief and joy following a breakup without even a suggestion of the lament so common in blues verses. Brown's lyrics simply state that she is ‘glad as can be’ that the ‘reason for [her] crying, is walking out the door’. ‘Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean’, offers a contrasting response to a similar situation. As was more typical of the musical divisions of labour at the time, ‘Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean’ was composed by a professional songwriting team and suggested to Brown by an Atlantic records A&R man (Brown and Yule Reference Brown and Yule1996, p. 78). Unlike the public address to an unnamed audience so typical of the blues, the viewpoint of ‘Mama’ is a private and intimate one: that of a daughter speaking directly to her mother about the ways in which she has been ill-used by her man. The first three lines of the first verse, what Patterson refers to as the ‘recitative’, summarize her protests against the mistreater (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Patterson's lyric transcription of ‘Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean’.Footnote 18

Missing from the song are any definitive statements that the protagonist of ‘Mama’ has any interest in calling off the relationship. She has complained to her friends about the situation (‘All my friends say they don't understand what's the matter with this man’) and now expresses her frustration to her mother, but at no point suggests that she should or would put an end to the treatment.

In the words given to Brown to voice, the ‘man’ of the song ‘makes’ the singer do something no less that four times. Twice this takes the form of actual actions where she is made to ‘call him honey’ and ‘squeeze him’. The other two instances refer to emotions elicited from her in the form of ‘disgust’ and ‘lov[ing] him madly’. Even when she acts or feels in these verses it is in direct response to the ‘man’. Taking into consideration the many models that came before it in which a mistreated lover leaves or takes revenge, one might be tempted to read ‘Mama’ as a song in which the protagonist lacks agency. From this perspective, ‘Mama’ could be understood as a less-than-assertive expression of femininity associated with submission and re-action. Two factors undermine this conclusion.

Patterson's presentation of ‘Mama’ belies an interpretation of the song strictly in terms of regret and powerlessness. Patterson's rendition is performed at a brisk tempo more likely to inspire dancing than sorrowful reflection and, with the exception of the ‘recitative’ sections, the recording is awash with ecstatic instrumental improvisation. As a rule, Patterson's delivery is light-hearted and confident throughout the song. Even in the ‘recitative’, where Patterson's voice stands alone against a sparse rhythm section accompaniment, her tone implies that that she does not altogether mind that her man ‘makes her love him madly’, even if she might prefer that he not ‘take her money’. A literal interpretation of the lyrics, it seems, does not tell the whole story. Patterson's setting of the song insinuates that while she feels trapped in an (at least imbalanced, at worst, abusive) relationship, it is, in part, her very desire for her lover that renders her incapable of leaving. In these terms the protagonist of the song may be powerless, but it is her own sexual desire that is beyond her control.

Even if the lyrics to ‘Mama’ are taken at face value alone, analysis of similar litanies present in the classic blues repertoire suggest a more nuanced reading, one in which the recitation of a deeply personal exchange in the public sphere can be understood as an act of feminist affirmation. As Angela Davis points out, to ‘unabashedly name the problem of male violence … so directly and openly may itself have made misogynist violence available for criticism’ (Davis Reference Davis1998, pp. 29–31). In other words, even if a woman being ‘treated badly’ was relatively commonplace, in early 1960s Britain so much as indirectly addressing such an issue was anything but common. Although lacking the overtly empowered stance of ‘It's All Over’ – viewed as a statement of hopeless desire, as public lament, or both simultaneously – ‘Mama’ could nonetheless serve as a vehicle through which Patterson could express positions that were at once familiar and Other.

The sexual assertiveness and empowered presence resident in the black women's blues verses above stood in contrast to the more staid representation of white middle-class femininity most often found on popular records at the time. The lyrics Ottilie Patterson chose to reproduce expressed an alternative notion of femininity that she may have hoped to embody despite her whiteness and Irishness. By embracing the alternative positions articulated in these songs, Patterson expressed, and offered to her listeners, what Angela Davis has referred to as ‘hints of feminist attitudes’ present in women's blues. Such vicarious exploration of black womanhood signified a way for the ‘slim Irish girl’ to communicate the unconventional possibilities afforded in these verses.

Ottilie's blues

Ottilie Patterson's notebook indicates that, in addition to the 12 tracks featured on R&B with Ottilie, other contemporary, popular R&B songs were also considered for the album, or at least were among Patterson's repertoire at the time. Positioned between ‘R.B. Blues’ and ‘Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean’ in her notebook, for example, are the lyrics to Little Walter's 1955 hit ‘My Babe’. ‘My Babe’ is followed later by the words to a 1956 single ‘Easy, Easy, Baby’ by Anne Cole (a singer best remembered as the artist who recorded ‘I Got My Mojo Working’ weeks before Muddy Waters), and Dinah Washington and Brook Benton's 1958 ‘Nothing in the World’. Furthermore, a set list written in pencil in the margin of a page in the notebook includes the above-mentioned songs, the tunes contained on R&B with Ottilie, and the Muddy Waters’ titles ‘Got My Mojo Working’ and ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’. That Patterson was performing, or at least listening to a considerably varied array of rhythm and blues records helps inform the spheres of influence Patterson may have drawn from when crafting her original R&B with Ottilie compositions.

‘Tell Me Why’

Of the two originals Patterson recorded in July 1960, ‘Tell Me Why’ takes a more conventional lyric approach. The song's refrain of ‘tell me why, why you and I have got to part?’ is a rather typical lament from the point of view of someone who has been left by a lover. Patterson explores many other lyric turns typical of such a song in the verses that follow. In the opening and closing verses, for instance, Patterson expresses her seemingly hopeless devotion to the now-absent man who caused her to change her ‘reckless’, fast-living ways, whom she loves ‘more and more … with each passing day’. While no justification for the lover's leaving is given in the lyric and there is no allusion to infidelity, Patterson perhaps hints at the reason for the split with the lines ‘I ain't good lookin’, and my clothes ain't fine’, although she counters this bit of self deprecation with: ‘but I'll feel your worries like they were mine’. Phrases like ‘you were troubled, and dissatisfied’ as well as many of the lines quoted above seem to have been borrowed almost wholesale from existing blues songs circulating in the British trad jazz revival scene at the time. Patterson's choice to leave out any sort of assertion of power or shift in tone seems somewhat unusual considering the songs she surrounds ‘Tell Me Why’ with on R&B with Ottilie. From a lyric perspective, the song is a rather straightforward expression of conventional white British femininity (c. 1960) expressed through a blues vocabulary. It is in terms of vocal approach and rhythmic feel instead that ‘Tell Me Why’ notably departs from the expressive expectations of trad jazz and early 1960s’ British pop music more broadly. In terms of feel, form, and vocal approach, ‘Tell Me Why’ instead closely resembles Ruth Brown's ‘R.B. Blues’.

Unlike the 4/4, 12-bar blues numbers that make up the vast majority of R&B with Ottilie, ‘Tell Me Why’ employs a 12/8 feel and an eight-bar blues form/harmonic progression; structural devices very similar to those found in ‘R.B. Blues (It's All Over)’ (see Example 1).

Example 1. Form/harmonic comparison of ‘Tell Me Why’ and ‘R.B. Blues’.

In her vocal performance Patterson employs melisma liberally in a manner that resembles Ruth Brown's approach on ‘R.B. Blues’. Following Brown's model (which she also emulates on her recording of ‘It's All Over’), Patterson alternates freely between syllabic and melismatic phrasing in ‘Tell Me Why’. This approach is on display in the seemingly improvised melodic embellishments found in the song's opening line (see Example 2) and in verse one when she follows the syllabic setting of ‘with each day’ at the end of measure two with a five-note melisma on the word ‘passing’ in measure three (see Example 3).

Example 2. ‘Tell Me Why,’ opening vocal line.

Example 3. ‘Tell Me Why’ vocal line, verse one.

‘Tell Me Why's’ direct emulations of stylistic conventions found on Ruth Brown's relatively recent ‘R.B. Blues’ – conventions similarly employed by many other women R&B performers in the 1950s – could be understood as a retort by Patterson to critics who would brand her a Bessie Smith impersonator exclusively ‘conjuring’ the voices of the distant past. In her prior work Patterson drew upon African-American performance conventions associated with the 1920s and 1930s to craft her revivalist sound, as she does on the Trixie Smith and Bessie Smith covers on R&B from Ottilie. As Laurie Stras notes in regard to the Boswell Sisters’ 1930s recordings, ‘three factors of vocal production – tonal variety (leading to greater expressiveness), [low] tessitura, and regional accent – provided the technical basis for the Boswells’ new sound, the sound that would be identified by their audiences as “authentically” black’ (Stras Reference Stras2007, p. 225). These three elements were likewise integral to Patterson's vocal approach prior to R&B from Ottilie. In ‘Tell Me Why’, however, Patterson expanded her expressive palate by embracing relatively new additions to women's commercial R&B vocal practice, elements that Annie J. Randall refers to as ‘gospelisms’ (Randall Reference Randall2008, p. 47). This term, Randall offers, encompasses a set of stylistic traits which include melismatic ‘improvised melodic flourishes or extended departures from the melody’, ‘text interpolation drawn from the black sermon tradition’ and ‘expressive non-verbal sounds’ (Randall Reference Randall2008, p. 47). Moreover, Patterson's choice of a 12/8 feel similarly works to associate her original composition with black gospel traditions and the 1950s’ popular R&B it inspired.

‘Bad Spell Blues’

The ‘side A, track 1’ selection on R&B with Ottilie, ‘Bad Spell Blues’ appears to be a song in which Patterson took a particular degree of satisfaction. Of the nine seemingly original songs and the six poems in her ‘R&B with Ottilie’ notebook, only ‘Bad Spell’ bears any kind of composer credit. Unlike these other works, ‘Bad Spell’ proudly displays ‘ME.’ at the top of the page (see Figure 5). Given the lack of attribution on other lyric sheets, this acknowledgement begs to be interpreted as an indication that Patterson looked to project herself through this composition and subsequent performance.

Figure 5. ‘Bad Spell Blues’ lyrics and performance notes.

From the song's opening fortissimo brass riff underneath a Little Walter-esque trill/shake played on clarinet, ‘Bad Spell’ announces itself as indebted to the Chicago blues idiom pioneered by Willie Dixon and Muddy Waters. Over the course of the four repetitions of this introductory riff, the track's dynamic recedes to mezzo piano before settling into a simple backing of drums, bass and banjo behind Patterson's first verse. This accompaniment consists of a persistent bass drum-snare backbeat, bass pedal-tone quarter notes, and three-eighth-notes-to-the-beat comping from the banjo that confirms a 12/8 meter and outlines the 12-bar blues form of ‘Bad Spell’. The horns return for the second and third verses after sitting out the introductory stanza, performing only a subdued, unison version of the opening riff behind a slightly intensified rhythm section groove in which the bass folds in the occasional eighth-note fill. Only in verse four does the accompaniment return to the dynamic level and intensity found in the opening figure. Even then, however, it is devoid of improvisational responses of any kind. As Patterson indicated with the ‘straight through’ direction at the bottom of her lyric sheet, she intended ‘Bad Spell Blues’ to be played without any of the instrumental solo responses commonly heard in trad jazz settings (see Figure 5). This arrangement contrasts starkly with the approach found on ‘Tell Me Why’ in which the more traditionally gender-conforming lyrics are accompanied by very active collective improvisation from clarinet, trumpet and trombone. This strategy of withholding the spotlight from her male accompanists – also employed in Patterson's recording of ‘Me and My Chauffer’ discussed above – allowed Patterson to foreground the words she composed for this song.

In a performance that is even more melismatic than ‘Tell Me Why’, Patterson sings of the troubles she has getting and keeping a man. The song opens with Patterson's suspicion that someone has put a spell on her. She then laments that, despite her obvious qualities, she is unable to attract the affections of the opposite sex. As a voodoo curse appears to be the cause of her troubles, she sets out to find a gypsy woman who will not only break the spell, but also imbue her with the power to have men come ‘begging ‘round her door’. ‘Bad Spell’ closes with Patterson exclaiming that if she can't get the man she wants, she'll ‘settle down with three or four’ – a gesture that seems to surpass even the empowered sexual subjectivity she expressed in her covers.

While many blues singers evoke voodoo, gypsy magic and mojo hands, perhaps no artist was more closely associated with such themes as Muddy Waters. It would appear that throughout ‘Bad Spell’, almost on a verse-by-verse basis, Patterson is making direct reference to Muddy Waters songs she not only heard him perform on British stages and in Chicago clubs, but was known to sing herself.Footnote 19 ‘I'm young and good looking, but my baby won't mess with me’, for example, could very easily be a reinvention of ‘I got my mojo working, but it just don't work on you’ (‘Got my Mojo Working’ 1956). ‘I'm going to some gypsy, she'll tell me the way that I can fix those men’, tracks nicely with ‘I'm going down to New Orleans, get me a mojo hand, I'm gonna show all you good-looking women, just how to treat your man’ (‘Louisiana Blues’ 1950). Furthermore, ‘I'm goin’ to make you men come running, and begging round my door’, echoes ‘I'm gonna make you girls, lead me by my hand, then the world will know, I'm the hoochie coochie man’ (‘Hoochie Coochie Man’ 1954). As Benjamin Filene notes, many of Waters’ best-known records – records like these – project a ‘stylized and exaggerated’ version of black life where ‘virility is prized and repeatedly proven’, ‘a supercharged version of southern culture … ruled by violence, sex and the supernatural’ (Filene Reference Filene2000, p. 103). It is this world and a persona akin to Waters’ that Patterson strives to conjure for herself in ‘Bad Spell’.

Although Patterson's R&B with Ottilie covers channel the assertive tone, expressive vocal performance, and unconventional representations of femininity found in established women's blues models, with ‘Bad Spell Blues’ Patterson moves beyond these prototypes in a striking manner. By adopting the sonic and lyric conventions of Muddy Waters, she inverts the typically masculinist lyrical tropes of Chicago blues into feminist statements. While he was by no means the only model for British rhythm and blues enthusiasts, Muddy Waters – or at least his voice on record, his musical aesthetic and his historical position as iterable model of black identity for white Britons – would come to serve as a central inspiration for the British rhythm and blues scene. The reproduction and (re-)presentation of performance practices (form, instrumentation, vocal technique, etc.) found in Waters’ records, much less the songs themselves, would constitute the aesthetic foundation of much of the British R&B to follow. That Patterson, as early as 1960, was performing, much less composing, in a style influenced by Waters demonstrates that this aesthetic foundation was laid well before, from a very different source, and with a very different result than what the accepted narrative would suggest.

Conclusion

Through the preceding examination of R&B with Ottilie, a more complicated British R&B history emerges. In all its complexity – as disregarded artefact filled with reproductions of canonical material; as a product associated with Chris Barber, the widely accepted ‘Godfather of British Blues’; as a woman's manifesto on the blues amongst a sea of masculinist representations; and as a premonition of a musical revolution – R&B with Ottilie serves as a uniquely positioned object through which the standard narrative of British R&B, and by association, the British Invasion, blues-rock, and Anglo-American popular music more generally can be reassessed.

R&B with Ottilie, an album which includes a female singer performing a broad assortment of rhythm and blues numbers, undermines many of the standard tenants of the history of British R&B. It would be noteworthy enough if it were merely the first concerted effort to revive and rework rhythm and blues. That it contains a woman covering/emulating black women's blues and inverting the typically masculinist lyrical tropes of Chicago blues into feminine statements, vicariously exploring assertive sexuality and alternative identities from both a masculine and feminine perspective – in the re-creation of black women's blues and her own original compositions alike – challenges the notion that British R&B was, from its point of origin, predominately motivated by male appropriation and vicarious expression of African-American hypermasculinity. Finally, as the first documented original British R&B from Britain's foremost blues performer of the day, it stands as a pivotal, if underappreciated landmark in the history of British R&B.

I want to end by offering that this reconsideration should not be treated as a wholesale invalidation of the standard British R&B narrative outlined at the outset of the article, nor do I think attention to records like R&B from the Marquee is misplaced. Although I have demonstrated that Blues Book Vol. 1: Rhythm and Blues with Ottilie Patterson deserves to be repositioned within this history, R&B with Ottilie is also notable for what it did not achieve and did not represent. While this album was a bold recording experiment in new sounds and a personal essay exploring the expressive possibilities of rhythm and blues, what it failed to do in an immediate sense was embody the interests and tastes of an emerging musical community. In contrast, Blues Incorporated's R&B from the Marquee documented the London R&B scene as it was taking shape. That R&B with Ottilie was widely ignored at the time and has not been subject to reclamation until now speaks not to the quality of the recording or contemporaneous popular taste, but rather to what forms of British R&B came to be valued, who was deemed qualified to perform R&B, which audiences valued these forms, and what socio-cultural ends the music served.