Introduction: “Manchester” of the NorthFootnote 2 and East

At the start of the nineteenth century, Łódź, Poland, and Tampere, Finland, became what in present-day terms would be called “special economic zones” with tax exemptions and other privileges. The population grew rapidly. In Finland, where feudal society was not fully developed, workers came to Tampere from the nearby countryside.Footnote 3 In Poland, particularly the abolition of serfdom in 1864 ignited a large migration of former serfs to Łódź.

At the turn of the century, both cities, lacking traditional, estate-based social structures, became centers for revolutionary mobilization with massive protests and strikes. The Russian Revolution of 1905 contributed to their deeply rooted images and self-images as “Red Cities.” The Red Declaration, calling for universal suffrage, was published in Tampere and the city was a battleground during the Finnish Civil War. In Łódź, a huge workers’ uprising over several days (“Łódź insurrection”) was brutally crushed by Cossack troops.Footnote 4 The first local elections after the proclamation of independence by Finland (1917) and Poland (1918) brought victory for the Socialist parties in both cities.

However, public perceptions of Łódź and Tampere were significantly different. Tampere's image was positive, “the beautiful city of factories” was appreciated for its input to the national economy, according to Haapala.Footnote 5 Meanwhile, the stereotypical image of Łódź as a “bad city,” with a large non-Polish population, ethnically-fueled conflicts, severe poverty, and inequality, was reinforced. The very fact that Łódź did not reproduce the urbanization and socio-economic patterns typical for “genuine” Polish cities was deeply troubling.Footnote 6

The Second World War did not bring major destruction to the infrastructure of either city. However, the ethnic, cultural, and social fiber of Łódź changed substantially. Jewish inhabitants, previously constituting one third of the local population, perished during the Holocaust. German inhabitants were displaced after the war. The city remained a center for light industries, which were perceived in socialist narratives as inferior and paid as such. Meanwhile, Tampere retained its position as the number one industrial town in Finland, benefiting from varied industry and the expansion of the socio-democratic welfare regime. The postwar period was also marked by the establishment of institutions of higher education in both cities (in 1945 in Łódź, and in 1960 in Tampere), which created a new, locally educated elite impacting cultural and intellectual life.Footnote 7

The fall of communism, particularly the collapse of the Soviet Union, was pivotal for Łódź; less so Tampere. While the Soviet Union had been a crucial trading partner, Finland was already integrated in the global economy. In 1993, both cities experienced a sharp spike in unemployment peaking at 23 percent.Footnote 8 In Tampere, the Nordic welfare state provided a safety net for most of the unemployed. Workers were also offered early retirement and re-education. Haapala observesFootnote 9: “In the more serious situation of the 1990s, the new Nokia-led high-tech sector became the saviour. It brought new jobs and remarkable tax revenues to the city. Most interestingly, much of the ‘old industry’ survived through its ability to develop new high-tech products within traditional fields. This was paralleled with growth of the city and region's inhabitants.”

In Łódź, deindustrialization was rapid. Seventy percent of the factories went bankrupt or were liquidated in the first half of the 1990s.Footnote 10 The textile workers did not have political protectors like their counterparts in the mining or shipbuilding sectors and did not receive any special welfare assistance. Since the 1990s, cheap labor has been considered the main competitive advantage of the city.Footnote 11 Łódź has lagged behind every other large Polish city in terms of economic conditions and social indicators.Footnote 12 Meanwhile, thanks to the Nokia-led ICT sector, Tampere has become a leading center for the knowledge economy. Both cities are currently transforming their infrastructure with an emphasis on making the city centers attractive, mainly for investors and tourists.Footnote 13

Memory policy and museums

Many studies have examined how memory is produced and maintained through various lieux de mémoire, such as archives, monuments, memorials, statues, or street names. In this paper, we aim at reconstructing official narratives or agendas as designed, produced, and implemented by public bodies and represented in state- or municipality-owned museums. This allows for partial reconstruction of institutionalized memory policy for they are a material proof of what is and what is not worthy of remembering and what should/could be forgotten without harm to the identity, culture, or political agenda realized by those who formulate policies.Footnote 14

The concept of memory policy, as defined by Nijakowski, has been applied. In his understanding, it “is every activity—conscious and unconscious, intentional and accidental which leads to hardening and grounding or changing of the collective memory.”Footnote 15

Museums shape and reify narratives about local/regional/national identityFootnote 16 and serve as agencies for the promotion of ideas defined by hegemonic ideologies. Hegemony here is understood according to Molden,Footnote 17 who claims:

[hegemony is] the ability of a dominant group or class to impose their interpretations of reality—or the interpretations that support their interests—as the only thinkable way to view the world. The dominated groups come to accept the interests of the dominant ones as the natural state of the world.

Certainly, the role of museums in the implementation of memory policy is twofold. Firstly, they operate internally as “containers of memory”Footnote 18 for local/regional/national audiences; visits to museums can constitute an important part of an educational agenda creating certain attitudes and beliefs. Secondly, museums are a key to country or city branding; they become “shopping windows” for tourists, visiting professionals, prospective future inhabitants, and sometimes investors. As Marschall claims,Footnote 19 these two functions are always intertwined, and marketing efforts are guided by the ideological frameworks of memory, reflected in the treatment of symbols, and official commemorative rituals clash with individual interpretations of the past when “consumed” by visitors.

Often industrial heritage is considered in terms of its spatial, material, and topophilic context,Footnote 20 as well as with regards to the transformation of the industrial landscape.Footnote 21 The topic of working-class heritage is usually studied within the same frameworkFootnote 22 rarely focusing on the social complexity of working-class identity.Footnote 23

We were particularly interested in how the role of the working class in the founding/building of each city was reconstructed. The category of myth was particularly relevant in approaching the issue, so the historical accuracy of the data stayed a secondary question. Attempting to reconstruct legitimized imagery about the social affairs, events, and stories, which are supposed to shape the emotions of the audience, we decided to include in the sample of resources the official publications of public museums as the most representative data for “authorised heritage discourse.”Footnote 24 Content analysis of publicly-produced documents is a well-established research approach for studying public policies, and we assumed that the official publications constituted a more “solid” and representative dataset than the contents of exhibitions, which frequently change. Over the course of interviews conducted with museum employees, we learned that printed publications are the only material “traces” of a discontinued exhibition.

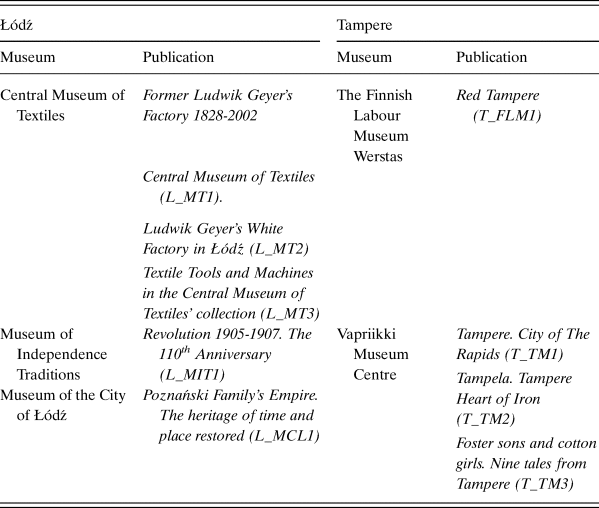

For the sake of methodological integrity and to avoid data selection bias, we included all publications (books, booklets, catalogues) referring to local socio-economic and industrial history produced by the museums and available in the museum shops (stationary and online) in autumn of 2018. While the sample was collected at a certain moment in time, the release dates ranged from 2006 to 2016. Six publications came from the Central Museum of Textiles, the Museum of the City of Łódź, and the Museum of Independence Traditions, and four from the Vapriikki Museum Centre and the Finnish Labour Museum WerstasFootnote 25 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Museums and publications included in the sample

Open coding enabled the identification of the main topics and storylines, actors, and events represented in the publications. In turn, theoretical coding was aimed at capturing all contexts in which the working class was represented. Thorough analysis of lexical tools and grammar structures stayed beyond the scope of this paper, as the corpus of data was not standardized in terms of language. While in Polish case, we were able to scrutinize the nuances by checking the Polish versions of the texts, for the Finnish case we relied solely on the English translations. As some of the publications under scrutiny are multi-authored, the sources are quoted by the codes (see Table 1).

Results

Particularly for Łódź, the reconstruction of the narratives concerning the working class was in some cases possible only through relational references to other social entities and actors, as the working class was rarely mentioned per se. Attention was paid to the content of the publications, but it was also important to analyze the omissions, to see what was vanishing from the official narrative. The summary of the main motifs is presented in Table 2 below. The research resulted in the formulation of three main threads for interpreting the data, which are outlined further in the article.

Table 2. The summary of main motifs

Industrial Revolution: Golden Age myth vs. linear path

Tannock states “As nostalgia always involves the dislocation of people from a particular time or place, its rhetoric embraces several key tropes, including the notion of a Golden Age and a subsequent fall, the story of homecoming, and the pastoral.”Footnote 26 The origin stories for the two cities portrayed by the museums under study differ substantially. In Tampere's case, it's the kick off for a continuous path toward modernity, while the story of Łódź reflects the Golden Age myth. This fundamental difference sets the framework for further representations of the collective actors in this history and the scope of their agency.

According to the City of the Rapids, a richly illustrated book edited by the Vapriikki Museum Centre, “The history of Tampere is part of the birth of the industrial world and modern society; it is the success story of capitalism, technology, democracy and education” (T_TM 1: 59). A combination of forces has been identified as drivers for the development of Tampere, which makes the efforts of particular individuals less significant. The establishment of James Finlayson's engineering workshop is seen as a founding moment for the city; not because of his personal virtues but because of a concurrence of factors, which made the town prosperous. The “pioneer” presented could have turned into a mythic “founding father” figure. However, the descriptions of Finlayson's entrepreneurial skills and his impact on city development are followed by the story of his ultimate failure and the bankruptcy that drove him away from Tampere. Consequently, subsequent stages in the city's history are presented as logically linked with broader global trends shaping opportunity for the city and its inhabitants.

In contrast, characteristics of the Golden Age myth are conveyed in the following paragraph from one of the publications from the Museum of the City of Łódź:

Łódź was the place where Ludwik Geyer's steam machine, the first in the Kingdom of Poland was introduced and in the end of nineteenth century, the great fortunes of Scheiblers. Grohmans and Poznański's were made. At the same time, it was the living space for different nationalities, Poles, Jews and Germans, for whom Łódź was ‘the promised land’. No other city experienced such dynamic development and in such a short time, became an important industrial centre (…) The year 1939 and outbreak of the Second World War broke the coexistence of the people of different nations forming the unique community of Łódź. It has not reborn ever after. (L_MCL1)

The time between the founding moment and the Second World War appears as a period of prosperity and harmony. The idyllic vision of a “promised land” free from industrial or ethnic conflicts, a community bonded by entrepreneurial spirit, which collapsed suddenly under the pressure of the history (the war), has been reproduced in various contexts by local officials, or in strategic documents referring to the industrial heritage and identity of the city. The Golden Age myth has clearly been the source of inspiration for the current elites who invented the postindustrial identity of the city.

The “secular” and “linear” story of Tampere facilitates the perception of continuity in its modernization and evolution from an industrial to a postindustrial socio-economic structure. In this context, individual stories of socio-economic advancement serve as proof of the organically progressive spirit of the city, alongside improvements in public infrastructure, housing conditions or changes in patterns of consumption, which are widely discussed in the publications under scrutiny. Also, affinity between the working population of industrial Tampere and the professionals of the twenty-first century becomes easy to imply. By contrast, with Łódź deprived of a large part of its social history, attempts to establish such connections become problematic.

Cross-class alliance vs. industrial paternalism

In both cases, local working-class history has been integrated into the broader picture of social relations and subjected to various forms of myth making. Fully aware that official memory presents versions of social history favorable to the dominant social forces, we still see significant differences between the stories about the industrial pasts of the two cities. In all the publications under scrutiny, the working class of Tampere seems to be presented as a player in a cross-class alliance, serving as an agent of change on equal terms with the capitalists. Not just the role of self-organization, but also the cooperation and negotiations between the two collective bodies is underlined. This theme in particular is widely used in subsequent chapters of “The City of the Rapids” (T_TM1), where the development of public infrastructure is predominantly framed as result of coalition building and consensus-making. The class conflict seems to “melt” in mutual efforts for the common good. The vocabulary of class struggle is absent from the narratives and the differing interests of the working class and entrepreneurs are mentioned only via general references to the 1905 Revolution.

Dichotomous class relations are at a certain point balanced by the appearance of a third, crucial actor. Local public administration serves as a mediating agent between the social forces. Its role is to assure that a cross-class consensus will be achieved and sustained, and that the outcomes will be beneficial for all citizens. It's technocratic rather than political, although a separate chapter has been devoted to ideological swings and party rivalry. City administrators manage the socio-economic and cultural changes affecting the city throughout the twentieth century. Their importance is underlined in paragraphs and a page-size photo devoted to the people employed by the city administration, but also by subchapters on the emergence of hard and social infrastructure for Tampere.

This approach is exemplified by the story of the establishment of universities in Tampere, which is presented as a result of “common will” by the people. Efforts, which began in 1911, were constantly discussed in public, and concluded only in the 1960s. City officials appear as key figures behind the decision by the government to relocate the School of Social Sciences from Helsinki to Tampere in 1956. This move triggered a new era in the development of the city. City administration was also instrumental in re-shaping the profile of the newly established higher education institutions: “Already by the end of the war, the decision-makers of the City of Tampere understood that traditional industry would not suffice and that the city required new avenues for success” (T_TM1: 242). During the 1990s downturn, they implemented various measures to alleviate the negative consequences of deindustrialization. Public authorities thus appear as the main manager of social change, guaranteeing smooth transitions on the way to modernity.

In Łódź, class relations are more difficult to reconstruct, as the lower classes barely exist in official museum narrations. The working population is presented as an object of industrial paternalism rather than collective actor. Passages from a book devoted to the heritage of the Poznański family (L_MCL1 2012) serve as a good example: “Great bourgeoisie was the key creative force for the economic institutions of the city” (L_MCL1: 51). Further, a reader learns that: “The phenomenon of profound social significance was the development of paternalistic relations between the owners and the employees. Various socio-patronal and cultural institutions were to bond workers with a factory and strengthen their conviction that the existing socio-economic arrangements are profitable for them (…) In Łódź, by the initiative and the manufacturers’ costs housing estates for the workers were developed” (L_MCL1: 54).

The engagement of the Łódź industrial bourgeoisie in creating public infrastructure and solving everyday problems is contrasted with the passive attitude of the Russian administration. The absence of the state as an agent of change creates another stark contrast between the narratives of the two cities. Here, it reinforces the mythical figures of entrepreneurs not only as the founding fathers of industry, and therefore the ones who paved the way for the development of the city, but also as do-gooders who took personal responsibility for the well-being of the inhabitants in the face of passivity by the Russian administration and the masses. The official narratives of Łódź museums largely omit the perspective of regular folk. They lack information about the grassroots organizations that formed at the bottom of the social structure, and also lack descriptions of the living conditions of the vast majority of the city's inhabitants. This top down approach to storytelling portrays industrialists as the only ones who could be credited with development in the city. From this perspective, the withdrawal of the “fathers” from the landscape of Łódź due to economic changes first in the interwar period, but foremost, under socialist rule, can truly be interpreted as a catastrophe. It amplifies the absence of public actors, when studying narratives about the socialist period. For example, the emancipatory story of the establishment of tertiary education in Łódź (six public universities), crucial in Tampere's case, is non-existent here. Both before and after 1989, an anonymous population deprived of enlightened guides and lacking its own agency, was doomed when exposed to systemic breakdowns.

Who built the city? Elite vs. popular perspective

Framing the working class as a collective actor in Tampere's history can be summarized in an excerpt from “Red Tampere,” a guide published by the Finnish Labour Museum. The introduction reads:

Tampere is a traditional working class city that was established in the shadow of smokestacks. The working people were active participants in workers’ associations, local trade unions and sports clubs and founded their own cooperative society, a bank, an insurance company and a theatre in the city. The Red Manifesto was delivered in Central Square in 1905, the year of the Great Strike, and thirteen years later the decisive battles of the Finnish Civil War took place in the same location. Tampere is full of the traces and stories of the working class life-the history of the city is red. (T_FLM1: 6)

The agency of the working population of Tampere is demonstrated not only by the active voice and enumeration of the practices and institutions established by the working-class community of the city but also by underlining that Tampere was the scene of founding events in labor movement history. The Łódź Insurrection of 1905 and the Finnish Civil War of 1918 were the most notable socio-political events for two cities. The way they are remembered in urban memory policies today is fundamentally different. In Tampere, a temporary exhibition at the Vapriikki commemorating the ninety-year anniversary of the Civil War was made permanent in recognition of its significance for the city's identity. In Łódź, there is no single permanent exhibition devoted to the Insurrection of 1905. A temporary exhibition commemorating the 110-year anniversary at the Museum of Independence Traditions was replaced in 2016 by an exhibition on the anniversary of the Baptism of Poland.Footnote 27 The brochure (L_MIT1) provides the most comprehensive depiction of the socio-economic situation of the working-class population in all studied corpus, but the insurrection is painted as a consequence of global processes and spirit of the times rather than concrete decisions made by local manufacturers and the exploitive nature of industrial relations in Łódź. One learns that “Wages were too low to ensure dignified and decent life,” “Diseases were spreading, first and foremost tuberculosis, which were triggered by malnutrition,” “Work was hard and dangerous,” and “Sexual harassment of young girls was not infrequent.” The revolution was triggered by the rise and radicalization of the Socialist working-class movement, Bloody Sunday, strikes in St Petersburg and all over Congress Poland, and the wave of school strikes against ethnic Russification. Much space is given to the negative consequences such as violence among the workers. A separate paragraph is devoted to depicting terrorist actions organized by the Combat Organization of the Polish Socialist Party. The only paragraph in the whole brochure that presents the manufacturers of Łódź as active and negative actors, is on the lockouts in 1906–1907: “In many of the factories in Łódź, the industrial owners took advantage of the Russian authorities’ support and started massive layoffs of striking workers. This tactic was aimed at pacifying the Revolution” (L_MIT: 19).

In Tampere, the life stories of intellectuals and professionals from working-class backgrounds comprise a considerable share of the individual biographies illustrating subsequent stages in the city's development. Particularly in “Red Tampere,” published by the Werstas, one can find numerous examples of intergenerational and intragenerational advancement. Minna Canth, a working class–born writer and social activist with a monument in the city, is portrayed as “protagonist for working women” (T_FLM1: 54). Väinö Linna, a working-class writer (photo showing him working at the cotton mill is reproduced in the book), Hugo Samela, one of the commanders of the Reds during Civil War, Kalle Kaihari, a Red Guard member, Olympic level sportsman, and businessman and Lauri Viita, author hailing from and praising the iconic working-class district of Pispala, provide similar stories of social advancement without cutting ties with the working-class roots.

Tampella foundry vs. Geyer's factory: A micro-case study

Tampere's Heart of Iron (T_TM2) is a monograph about the Tampella foundry. The story of the factory, important both to local and national industry over the course of almost two centuries, is contextualized in the local, regional, national, and global developments that influenced both the industry and the manufacturer. The roles of owners and managers is presented and their virtues acknowledged, yet they are not the main characters in the book. The lives of regular “foundry folk,” impacted by economic ups and downs, take the limelight. The story of Tampella through the tumultuous twentieth century is told through the life of one of its employees, Reino Jokinen, a skilled mechanic, who was born in 1910 and remained connected with Tampella until his death in 1998. The descriptions of his military service, sport successes, professional development, political engagements, private life, and working and housing conditions paint a multidimensional picture of the city and the foundry. Another crucial storyline in the book concerns the technological advances that influenced iron production. The role of engineers and scientists is highlighted and the book provides readers with information about the technical knowhow that enabled the successes of the foundry.

None of the factories in Łódź have been described as comprehensively, although their histories have been included in exhibitions organized by local museums. A catalogue published by the Central Museum of Textiles focuses on the development of the Ludwik Geyer cotton factory. The so-called White Factory, the current home of the museum, was the core building for one of the biggest industrial plants in Łódź. Established in 1828, it reflected all major socio-economic and political changes of the nineteenth and twentieth century, as it was the oldest and longest existing enterprise in Łódź. However, the story is told in thirteen pages, while the rest of the publication consists of illustrations and the depiction of artefacts gathered and exhibited in 2002.

The story of the factory is presented mostly from a macro perspective: “The factor which unexpectedly stimulated development of the Geyer's enterprise, was a new custom tariff introduced in November 1831 as a part of pressure after November uprising” (L_MT1: 5). The founding father of the factory, Ludwik Geyer, is the sole active individual in the narrative. His arrival in Łódź as a young “specialist in dying and printing on textiles” is described in detail: “[he] declared the will to inhabit there. He also presented to the Governmental Committee for Internal Affairs and Police his claims, among others he demanded a license for the import of a considerable amount of yarn and cotton fabric with lowered duty” (L_MT1). The high level of individual agency is stressed by expressions like “putting up claims” or “signing a contract.” The top managers working for the Geyers are also mentioned as the initiators and organizers of the social and cultural life of the factory but only one by name.

The factory workforce is depicted differently. “The collapse of the wool industry caused the pauperization of weaving craftsmen who turned to cotton fabric production and, facing mass unemployment, were forced to work for Geyer for minimum wages” (L_MT1: 5). The factory's growth is illustrated through an impersonal list of investments in machines, buildings, and land, as well as production gains, bank loans, and employment: “The employment reached the number of 655 workers and the value of yearly production reached 487 thousands roubles” (L_MT1: 7). The workers’ uprising in 1905 is acknowledged as only one of the factors impacting the local economy. The war period is summarized through the lens of Polish identity as manifested by the Geyers and repressions the family suffered under Nazi occupation. The reorganization of Polish industry under the socialist state, as well as the struggles and final bankruptcy of the state-owned factory, are depicted in the same detached manner, mentioning “major investments,” restoration of socio-cultural organizations, and the development of corporate welfare institutions within the enterprise.

Although analysis of physical space goes beyond the scope of this paper, we cannot ignore the fact that the everyday life of Tampella's workers has been meticulously reconstructed in an open-air museum in the former working-class district Amuri, whereas the small open-air area in the Central Textile Museum in Łódź comprises of a few houses from different parts of the region and does not give visitors any insight into the lives of the local working population.Footnote 28

Discussion and conclusions

Even at first glance, the genres of publications sampled differ substantially. The story of industrial Łódź is told mostly through exhibition catalogues aimed at a narrow public, formal in tone, and full of technical jargon. The four books about Tampere focus on popular history and seem to invite a much broader, still educated group of readers, the most extreme example being a graphic novel telling the city's history from the Stone Age to the twenty-first century in sixty pages (T_TM3).

Our analysis determined three main themes, where notable differences between the official narratives could be identified. The first is the “founding myth” for each city and general approach to its history. We argue that the linear and “secular” approach to the past typically found in Tampere publications left more space for the various collective forces that shaped the city over time, while the “Golden Age” approach applied in Łódź, focuses attention on “founding father” figures. Secondly, although both cities’ narrations present rather sanitized visions of social relations, the workers of Tampere are presented as actors in a cross-class alliance, while the working class of Łódź is presented as beneficiaries of industrial paternalism. Finally, this elitist viewpoint enables effective silencing of the popular perspective, which in the case of Tampere, becomes a handy tool for constructing a coherent vision of the pathway toward modernity while in Łódź tends to marginalize socio-economic inequalities, conflicts, and the trauma they inflicted.

NettleinghamFootnote 29 reminds, drawing on Byrne'sFootnote 30 conceptualizations, that deindustrialization is not the process of vanishing one form of production but rather the vanishing of an ascribed identity of a town, city, community. Strangleman, Rhodes, and LinkonFootnote 31 show that the loss of identity is accompanied by objective economic and social injury, hardships to make ends meet, fragility of occupational situation, and insecurity, which is the permanent contemporary characteristic of the labor force, replacing the working class also in the semantically changing legal definitions.Footnote 32

In the context of Łódź, identity is lost not only in material and economic terms. It is the unavoidable cost of transformation from a socialist to market economy, but as this research shows, also the vanishing from official memory propagated by the crucial official bodies of the city.

The most evident interpretation of the above-depicted differences refers to the specificity of post-communist discourses, as Molden puts itFootnote 33: “For example, after 1989, it has become all but outrageous to argue, in mainstream media and discourse, outside the paradigms of market liberalism, as its alternatives (communism, socialism) have been proclaimed historical errors that failed to survive the evolutionary competition of ideas. The corresponding memory practice is the delegitimization of the ‘Communist experience’ within the master narratives of European history.”

In this respect, the hegemonic discourse extracted from the official narratives of the museums locates the history of the working class in the city of Łódź outside of the boundaries of legitimate public memory. This can be partially explained by backlash against the rhetoric of communist ideology from the time of Polish People's Republic. It seems that, at least in the case of Łódź, the official discourse after the 1989, either by omission or by purposely designed policy, neglected the presence of some formerly praised social categories. This bears striking resemblance to what WacquantFootnote 34 described as a broader pattern of “invisibility of the working class in the public sphere and social inquiry over the past two decades.” It also refers to historic inquiry, which for the last three decades left aside the topic of labor and the working class in Łódź, until 2016 when the new monograph was published.Footnote 35 But this is apparently a much broader problem and a noticeable difference in Polish and Finnish historiography and should be briefly addressed here. The Labour Archive in Helsinki, the oldest of several institutions documenting workers’ life in Finland, was established in 1909 and has been run by a dedicated foundation since. Development of the social history paradigm in Poland has never been institutionally supported in a relevant way.

Additionally, the topic of the working class is unavoidably intertwined in Poland with the period of communism and perceived as an unattractive, unwanted, and unpleasant part of history associated on the one hand with backwardness and on the other with an oppressive ancién regime. Since museums are important for creating desirable public images for cities and communities, their agenda is very much oriented toward creating a message that the dominant groups perceive as attractive for tourists and other guests. A “socialist heritage”Footnote 36 may be seen as an obstacle here. Since the collapse of the textile industry, the municipal authorities of Łódź have desperately been looking for a new identity, trying to “polish” the history of the industrial city, resulting in negligence of its working class heritage since it's connoted with communist ideology and the inefficient socialist economy of a bygone epoch.Footnote 37 This has been achieved through a symbolic reappraisal of the capitalist beginnings of the city, going as far as using the title of the book by Polish Nobel-prize winning author Władysław Reymont in a promotional slogan “Promised land—once again!” In this way, the epic about the development of capitalist industrial relations in the late nineteenth century was completely stripped of its bitter irony though the ruthlessness of the capitalists and the hardship of the impoverished working class were the main themes of the book (originally published in 1899).

This kind of re-working of collective memory could be attributed to institutional and political forgetting, which in Connerton's prominent typologyFootnote 38 is crucial in constituting of a new identity. This type of forgetting is supposed to result in: “the gain that accrues to those who know how to discard memories that serve no practicable purpose in the management of one's current identity and ongoing purposes. Forgetting then becomes part of the process by which newly shared memories are constructed because a new set of memories are frequently accompanied by a set of tacitly shared silences.”

An additional, nonexclusive explanation can also be formulated. Haapala elaborates on the long lasting attachment of the local elites and general public in Tampere to their industrial-based heritage, pointing to the dissimilarities in social structure in Poland and Finland as one of the sources of the differentiationFootnote 39:

Tampere is very much known in Finland for its industrial history and people living there have always identified themselves with this industrial history. (…) Tampere has a strong reputation for this and it has always been so and still is. Then, Nokia invested in Tampere and many other high tech companies did and they also used this reputation of Tampere as an industrial city, only now it is a high tech industry. But this is continuation of the same story. (…) Tampere in addition has a tradition of being a worker's city and in a positive way. We all are workers’ kids. And even today people are proud of this heritage. Additionally, Finnish nobility and aristocracy was very weak compared to the Polish nobility and the number of Finnish capitalists was always limited, so Finland was always a society of peasants and workers And middle class intellectuals or civil servants were almost always kids of workers or peasants. The labour movement has a very strong tradition of remembering their own heroes even though the number of active members is getting lower and lower, there are new left coalitions attracting new people.

His observation adds to an already interesting puzzle, if the dominant position of the nobility within Polish society did not derive from economic capital ownership in fact, both societies lack their own capitalist class mythology. But as Tomasz Zarycki and Rafał Smoczyński showFootnote 40 in Poland, public debate has been, to a large extent, dominated by the narratives formulated within the “intelligentsia-nobility” paradigm. Particularly the intelligentsia, this specific East-European social stratum, has dominated the symbolic space in Poland in a longue durée as the crucial force for setting public agenda in post-feudal society. Working-class narratives and industrial city per se do not fit into it, and therefore could easily be excluded from official memory policy.

The working hypothesis—to be tested in the following studies—would thus be that despite (or even in contradiction to) the socio-economic exceptionality of Łódź, local cultural and political elites would rather seek confirmation of their own class identity by reproducing national narratives and mythologies than attach themselves to an urban organism, which since the beginning has been rejected as a “bastard city.”Footnote 41 The current debates, also locally in Łódź, are shaped under the strong influence of broader national mythology, which is dominated by gentry-intelligentsia imagery. The “houses of the manufacturers” (the Geyers, Poznanskis, Scheiblers, Herbsts) fulfill the gap in non-existing nobility in the local imagination. Even if current elites cannot easily present themselves as descendants of the industrial founding fathers who were mostly of Jewish and German origin, they can both express their cosmopolitan longings by cultivating the myth of Łódź as the promised land of “four [coexisting] cultures” and construct “founding father” figures using their own symbolic toolbox, with paternalism as the main frame to describe class relations. In practice, museums as institutions of cultural conservation and consecrationFootnote 42 tend to focus on the (perceived) universal aspects of heritage and obscure or devaluate other forms of identity.

Finally, we can draw on Smith'sFootnote 43 argument about the performative aspects of heritage as a meaning-making process linked with the negotiation of various social and political narratives addressing collective identity. The notable differences between the tales of industrial past as told by the museums of Łódź and Tampere at some point reflect the differentiation between “progressive” and “reactionary” nostalgia as defined by Laurajane Smith and Gary Campbell.Footnote 44 This terminology, while addressing the emotional processes occurring among community members, also deals with the tension between the empowering and disempowering potential of industrial heritage. Silencing of the collective experiences shared by the majority of citizens, objectified by official discourses, cuts off their descendants from an important source of self-reflection.

One of the crucial factors contributing to the difference stems from the fact that memory policy planning in Łódź seems almost exclusively a top down process with local, municipal elites being the main decision-makers. A bottom up approach would take into account the impact of mass organizations, such as labor unions or left-aligning political parties, in defining industrial tradition as the source of working-class pride. Notably, while both cities host national institutions aimed at shaping industrial memory, the Central Museum of Textiles in Łódź is supervised by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and the Municipality, while the Finnish Labour Museum is maintained by an association that includes a trade union and co-operative movement.

In Tampere, significant effort was made to showcase the city's linear path from a traditional industrial stronghold to frontrunner in the knowledge-based economy. Official narratives pay respect to the city's industrial roots and underline the agency of the working class as a driving force for its development. At the same time, Łódź, in aspiring to the label of a creative city, officially neglects its working-class roots. Future studies could analyze the interplay between various institutions and class-based interest groups in developing the memory policy agendas in the two cities. It would require determining the extent of the independence of local institutions from political pressures.