Introduction

Neurocognitive impairment is a well-established feature in bipolar disorder (BD), even in the early stages of disease (Pope, Mazmanian, & Sharma, Reference Pope, Mazmanian, Sharma and Uguz2016). It is present also in many cases during euthymic periods and is an important determinant of psychosocial functioning (Pope et al., Reference Pope, Mazmanian, Sharma and Uguz2016). Although neurocognition has been more exhaustively studied, over the past decades there has been an increased interest in the study of social cognition (SC) (Varo et al., Reference Varo, Jiménez, Solé, Bonnín, Torrent, Lahera and Reinares2019, Reference Varo, Solé, Jiménez, Bonnín, Torrent, Valls and Reinares2020) which is defined as the ability to detect, process, and use social information to manage interpersonal functioning and social behavior. SC deficits may produce significant daily difficulties given the crucial importance of SC for social relations and well-being (Miskowiak & Varo, Reference Miskowiak and Varo2021). SC encompasses five distinct areas, namely (i) emotional processing, (ii) theory of mind, (iii) attributional bias, (iv) social perception, (v) social knowledge (Green, Horan, & Lee, Reference Green, Horan and Lee2019). In BD research, the study of SC has focused mainly on emotional processing, which has been also conceptualized as emotional intelligence (EI) (Samamé, Martino, & Strejilevich, Reference Samamé, Martino and Strejilevich2015), and generally measured by means of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) (Mayer, Salovey, Caruso, & Sitarenios, Reference Mayer, Salovey, Caruso and Sitarenios2003).

Deficits in EI have been detected in patients with chronic BD (Aparicio et al., Reference Aparicio, Santos, Jiménez-López, Bagney, Rodríguez-Jiménez and Sánchez-Morla2017; Frajo-Apor et al., Reference Frajo-Apor, Kemmler, Pardeller, Huber, Macina, Welte and Hofer2020; McClure et al., Reference McClure, Treland, Snow, Schmajuk, Dickstein, Towbin and Leibenluft2005; Samamé et al., Reference Samamé, Martino and Strejilevich2015; Varo et al., Reference Varo, Jiménez, Solé, Bonnín, Torrent, Lahera and Reinares2019, Reference Varo, Solé, Jiménez, Bonnín, Torrent, Valls and Reinares2020). However, the evolution of EI throughout the course of BD is unclear due to the paucity of studies that have examined the deficits in EI in patients experiencing a first episode mania (FEM) (Daros, Ruocco, Reilly, Harris, & Sweeney, Reference Daros, Ruocco, Reilly, Harris and Sweeney2014; Szmulewicz, Lomastro, Valerio, Igoa, & Martino, Reference Szmulewicz, Lomastro, Valerio, Igoa and Martino2019) and the lack of longitudinal studies on EI of these patients. It remains to be solved whether the deficits are present since the beginning of the disease (i.e. as primary deficits) and remain stable from early stages to chronicity, or whether they emerge and worsen as a result of the burden of disease related with the chronicity of the illness (i.e. as secondary deficits). Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no study so far has assessed EI in FEM patients in comparison with those in later stages of BD.

Previous evidence for the role of EI for patients suffering from a non-affective first episode psychosis (FEP) has been reported (Sanchez–Gistau et al., Reference Sanchez–Gistau, Manzanares, Cabezas, Sole, Algora and Vilella2020). EI was found to be altered in non-affective FEP patients at onset and its impairment represents a stable pattern and a relevant feature of early schizophrenia (Green et al., Reference Green, Bearden, Cannon, Fiske, Hellemann, Horan and Nuechterlein2012). Schizophrenia and BD share a chronic clinical course with impairments in neurocognitive and clinical features, although with different levels of severity (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Altshuler, Glahn, Miklowitz, Ochsner and Green2013). As a consequence, patients with a FEM might present a similar but subtler pattern of EI abnormalities than non-affective FEP patients. To date, no study has investigated the association between socio-demographic, clinical, neuropsychological variables and EI among patients with a FEM. A better comprehension of the relationship between these variables and EI performance would have implications in understanding the nature, trajectory, and clinical relevance of the difficulties on this SC domain in the early stages of BD. Considering these gaps in the literature, the main aim of the present study was to explore EI using the full version of the MSCEIT in patients after a FEM in comparison with patients with chronic BD and healthy controls (HC). Also, the secondary aim was provided insight on the potential contribution of socio-demographic, clinical, and neurocognitive variables on EI performance in patients after a FEM. We hypothesized that FEM patients would present intermediate EI performance between HC and chronic BD, and their performance would be influenced by neurocognitive performance, clinical and socio-demographic variables.

Material and methods

Participants

Data were pooled from two projects developed by our research group. The first project recruited FEM patients as part of a 2-year longitudinal multicentric study including the Bipolar and Depressive disorders Unit of IDIBAPS-Hospital Clinic in Barcelona, FIDMAG Research Foundation, and the University Hospital Institut Pere Mata. The second project recruited cross-sectionally chronic BD patients both at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona and at mental health services in Oviedo. HC were recruited through advertisement at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona. The four centers cooperate under the umbrella of the Spanish Research Network on Mental Health (CIBERSAM) (Salagre et al., Reference Salagre, Arango, Artigas, Ayuso-Mateos, Bernardo, Castro-Fornieles and Vieta2019).

The inclusion criteria for FEM patients, evaluated at baseline, were: (i) aged between 18 and 45 years old at the time of first evaluation; (ii) having experienced their FEM (with or without psychotic symptoms) over the previous 3 years; (iii) being in full or partial remission [Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 17-item (HDRS-17) (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton1960; Ramos-Brieva & Cordero-Villafafila, Reference Ramos-Brieva and Cordero-Villafafila1988) ⩽14 and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (Colom et al., Reference Colom, Vieta, Martínez-Arán, Garcia-Garcia, Reinares, Torrent and Salamero2002; Young, Biggs, Ziegler, & Meyer, Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer1978) ⩽14]. The inclusion criteria for patients with BD were: (i) aged over 18 years old; (ii) fulfilling DSM-IV-TR criteria for BD type I (BD-I) and (iii) being euthymic (HDRS-17⩽8, YMRS⩽6), at least in the 3 months before the inclusion. Patients could have experienced more than one affective episode over the previous 3 years, could then be considered within their early-stage BD illness.

Exclusion criteria for both FEM and BD patients were the presence of (i) a mental intellectual disability [defined as intelligence quotient (IQ) <70]; (ii) presence of any medical condition affecting neuropsychological performance; (iii) alcohol/substance dependence in the previous year to study inclusion; (iv) having received electroconvulsive therapy in the 12 months before participation.

All patients were under stable treatment regimen.

HC without current or past psychiatric history, meeting the same exclusion criteria as patients, were recruited via advertisement. In addition, HC were asked if they had first-degree relatives with psychiatric disorders.

The study was carried out following the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was reviewed by the ethical committee of the four institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Clinical assessment

In order to gather clinical data, all patients were assessed by means of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID-I-II) (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, Reference First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams and Benjamin1997a, Reference First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams and Benjamin1997b). The YMRS and HDRS-17 scores were used to evaluate the severity of manic and depressive symptomatology, respectively. All the participants also completed the Functional Assessment Short Test (FAST) (Rosa et al., Reference Rosa, Sánchez-Moreno, Martínez-Aran, Salamero, Torrent, Reinares and Vieta2007), a scale designed to assess psychosocial functional impairment in psychiatric patients, with higher scores indicating poorer psychosocial functioning. The full description of other clinical variables is reported in the online Supplementary Material.

Emotional intelligence assessment

EI was evaluated using the Spanish version of the MSCEIT, V2.0 (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Salovey, Caruso and Sitarenios2003). This instrument consists of 141 items and provides eight task scores that measure the four branches of EI: (i) perceiving emotions: to recognize and to appraise emotions accurately; (ii) using emotions: to access or generate feelings when they facilitate thoughts; (iii) understanding emotions: to understand complex emotions and how emotions transition from one stage to another, to recognize the causes of emotions, and to understand relationships among emotions; (iv) managing emotions: to stay aware of one's emotions, and to solve emotion-laden problems. The perceiving emotions and using emotions branches are assigned to the experiential area, while the understanding emotions and managing emotions branches are assigned to the strategic area. The test provides an overall score, the EI Quotient (EIQ), and also scores in the two areas, in the four branches and in each of the specific tasks. Lower scores indicate poorer performance in EI. The average range of EIQ is 100, with a standard deviation (s.d.) of 15.

Neuropsychological assessment

All participants were evaluated using a comprehensive neuropsychological battery exploring different cognitive domains: processing speed, working memory, verbal learning and memory, visual memory, executive functions and attention. The neuropsychological battery comprised the digit-symbol coding, symbol search, arithmetic, digits, and letter-number sequencing subtests from Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III) (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997), phonemic (F-A-S) and categorical (animal naming) components of the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) (Patterson, Reference Patterson, Kreutzer, DeLuca and Caplan2018), the Trail Making Test-A (TMT-A) and Trail Making Test-B (TMT-B) (Reitan, Reference Reitan1958), the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) (Delis, Kramer, Kaplan, & Over, Reference Delis, Kramer, Kaplan and Over1987), the Rey Osterrieth Complex Figure (ROCF) (Rey, Reference Rey2009), the computerized version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) (Heaton, Chelune, Talley, Kay, & Curtiss, Reference Heaton, Chelune, Talley, Kay and Curtiss1993), the Stroop Color-Word Interference Test (Golden, Reference Golden1994), and the Continuous Performance Test-II (CPT-II), version 5 (Conners, Reference Conners2002). Finally, estimated IQ was assessed with the (WAIS-III) vocabulary subtest (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997).

Statistical analysis

Comparison of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics among groups (FEM, BD, and HC) was carried out using χ2 tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. The Tukey's test was carried out for post-hoc comparisons to identify pair-wise differences between groups. Effect sizes (Glass's d) were also calculated to estimate the magnitude of the differences between the groups. Neurocognitive tests raw scores were standardized to z-scores based on HCs' performance (for further information on the calculation of the composites of neurocognitive domains, see Supplementary Material). Performance on MSCEIT and the neurocognitive domains was compared across the three groups using generalized linear models. All models were adjusted for those clinical and socio-demographic variables for which the three groups differed significantly. Then, a Bonferroni post-hoc correction was applied when significant main effects were present when comparing the three groups, in order to identify pair-wise differences between groups. Estimated marginal means, adjusted for the other variables in the model, were reported for each variable of interest (i.e. EIQ), as well as the 95% confidence interval (CI), their mean difference (MD) and its standard error (s.e.).

Moreover, exploratory analyses were conducted to satisfy our secondary aim. In order to assess which socio-demographic, clinical, and neuropsychological variables were associated with IEQ in the FEM and in the BD groups, we first performed Pearson bivariate correlations to identify those continuous variables significantly associated with EIQ. For categorical variables (i.e. sex), Student's t test was run to evaluate the distribution of EIQ. Only those variables with a p value ⩽0.05 were then entered into a hierarchical multiple regression model, aimed at evaluating the association between socio-demographic, clinical, and neuropsychological variables and EIQ.

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The total sample included 184 participants: 48 patients with a FEM in full or partial clinical remission, 75 euthymic BD patients and 61 HC. Socio-demographic variables among groups are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic and clinical variables of first episode mania (FEM) or bipolar disorder (BD) patients and healthy controls (HC)

BD, bipolar disorder; FAST, Functioning Assessment Short Test; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IQ, intelligence quotient; MDE, major depressive episode; s.d., standard deviation; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

*Only statistically significant or almost significant comparisons are reported. Bold for statistically significant values.

a Missing information for seven FEM. Four FEM and 14 BD patients had no history of hospitalization.

b At time of evaluation.

Clinical features among the groups

Regarding clinical variables, there were significant differences between patient groups (FEM and chronic BD) and HC in the total HDRS-17 (p < 0.001) and YMRS scores (p < 0.001), as well as in the overall psychosocial functioning (p < 0.001). Both patient groups presented more subsyndromal depressive symptoms than HC (BD v. HC p < 0.001, FEM v. HC p < 0.001, respectively), whereas chronic BD patients exhibited more subsyndromal manic symptoms than HC (p < 0.001). No statistically significant differences were found in subsyndromal symptoms between patient groups. Significant group differences in the FAST total score were observed for both the patient groups, presenting significantly decreased functioning compared to HC (p < 0.001). In addition, chronic BD patients showed poorer psychosocial function than patients in the FEM group (p < 0.001).

Significant differences were observed in the comparison between chronic BD and FEM patients in age at first hospitalization (p = 0.009), being lower in the case of the FEM group (p = 0.009), but not regarding the polarity at onset (p = 0.265) or the presence of family history for either BD (p = 1.000) or major depressive disorder (p = 0.986). Groups differed in terms of duration of illness (p < 0.001) and total number of episodes (p < 0.001). Patients after a FEM experienced an average of 1.19 episodes of mania whilst BD chronic patients an average of 3.62.

Emotional intelligence performance

Patients in the FEM group performed similarly to HC on MSCEIT Total score (online Supplementary Table S1, Fig. 1) and all measures of MSCEIT (online Supplementary Table S1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Emotional intelligence quotient with error bars in the three groups.BD, bipolar disorder; FEM, first episode mania; HC, healthy controls; MSCEIT, Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Intelligence Test.

Fig. 2. Mean MSCEIT scores with error bars in the three groups. BD, bipolar disorder; FEM, first episode mania; HC, healthy controls; MSCEIT, Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Intelligence Test.

Significant differences were found for EIQ (p = 0.005) and in the MSCEIT understanding emotions branch (p = 0.007), even after controlling for age, subsyndromal manic and depressive symptoms. Bonferroni post-hoc testing revealed that BD patients presented significantly lower EIQ than HC (MD = 10.09, s.e. = 3.14, p = 0.004) but no difference was found neither between HC and FEM patients (MD = 2.69, s.e. = 3.56, p = 1.000) nor between FEM and chronic BD patients (MD = 7.40, s.e. = 3.61, p = 0.121).

In addition, BD patients performed more poorly than HC on the understanding emotions branch (MD = 7.46, s.e. = 2.53, p = 0.010). A trend-level difference was reported between patient groups, with BD patients showing lower scores than those in the FEM group (MD = −6.84, s.e. = 2.93, p = 0.056). No significant difference was reported between FEM patients and HC (MD = 0.62, s.e. = 2.87, p = 1.000).

Neurocognitive performance

Concerning neurocognitive domains, there was a main effect of group in terms of processing speed (p < 0.001), verbal memory (p < 0.001), working memory (p < 0.001), executive functions (p < 0.001), visual memory (p = 0.033), and attention (p < 0.001), after controlling for age, subsyndromal depressive and manic symptoms (online Supplementary Table S1, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Neuropsychological composite mean scores with error bars in the three groups. BD, bipolar disorder; FEM, first episode mania; HC, healthy controls; PS, processing speed composite; VM, verbal memory composite; WM, working memory composite; EF, executive functions composite; VisM, visual memory composite; AT, attention composite.

Bonferroni post-hoc pair-wise comparisons between groups revealed that FEM patients performed worse than HC on processing speed (MD = 0.96, s.e. = 0.24, p < 0.001), executive functions (MD = 0.83, s.e. = 0.30, p = 0.015), and attention (MD = 1.02, s.e. = 0.26, p < 0.001), but not on verbal, working, and visual memory. On the contrary, FEM patients performed better than chronic BD patients on processing speed (MD = 0.97, s.e. = 0.25, p < 0.001), executive functions (MD = 1.02, s.e. = 0.30, p = 0.002), and attention (MD = 1.79, s.e. = 0.28, p < 0.001), but not on verbal, working, and visual memory. Chronic BD patients performed significantly worse than HC on all neurocognitive domains: processing speed (MD = 1.93, s.e. = 0.22, p < 0.001), verbal memory (MD = 1.00, s.e. = 0.24, p < 0.001), working memory (MD = 0.72, s.e. = 0.18, p < 0.001), executive functions (MD = 1.85, s.e. = 0.26, p < 0.001), visual memory (MD = 0.51, s.e. = 0.20, p = 0.035), and attention (MD = 2.81, s.e. = 0.21, p < 0.001).

Socio-demographic, clinical, and neurocognitive variables associated with EIQ in FEM patients

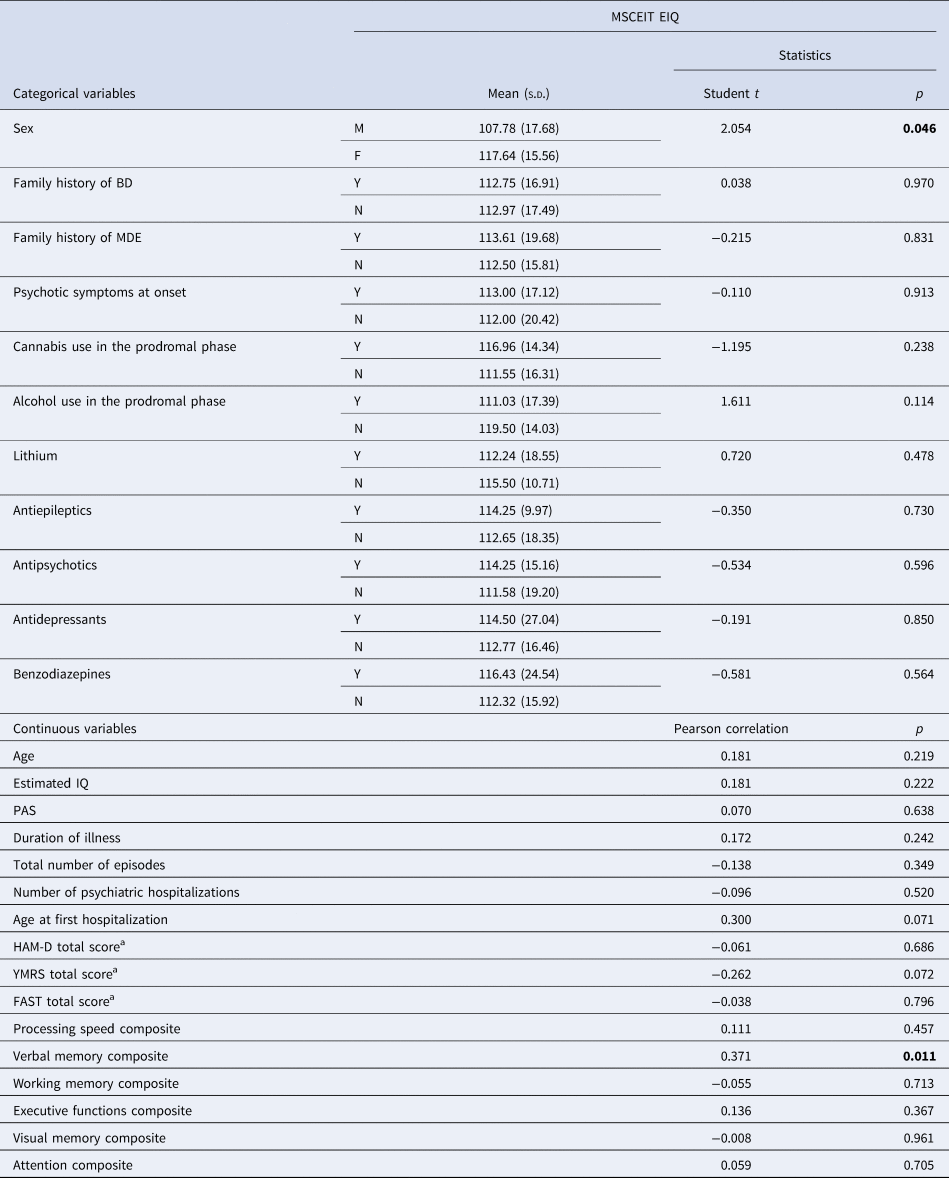

In FEM patients, lower EIQ correlated with poorer performance in verbal memory (r = 0.371, p = 0.011). Also, male patients showed lower scores in EIQ than females (t = 2.054, p = 0.046) (see Table 2). No other clinical variable correlated with EIQ.

Table 2. Correlations between MSCEIT Emotional Intelligence Quotient (EIQ) and socio-demographic and clinical variables in first episode mania (FEM) patients

BD, bipolar disorder; EIQ, Emotional Intelligence Quotient; FAST, Functioning Assessment Short Test; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IQ, intelligence quotient; MDE, major depressive episode; PAS, Premorbid Adjustment Scale; s.d., standard deviation; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

Bold for statistically significant values.

a At time of evaluation.

After including the variables significant in bivariate analyses in a hierarchical regression model [F (2,43) = 6.202, adjusted R 2 = 0.188, p = 0.004], both male sex (β = −0.293, p = 0.034) and the verbal memory domain (β = 0.374, p = 0.008) were significantly associated with EIQ, with a higher effect exerted by verbal memory performance.

Results for the chronic BD groups are reported in online Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively assess EI in patients after a FEM using the full MSCEIT version. The present study of EIQ in fully or partially remitted FEM (n = 48) v. chronic BD-I (n = 75) and HC (n = 61) showed three main findings. While patients after a FEM presented intermediate EIQ scores between HC and chronic BD, with EIQ scores significantly lower in BD than HC, in the MSCEIT branches, FEM patients' performance was globally comparable to HC. In addition, lower performance in understanding emotions branch was found for chronic BD patients in comparison with HC. Whilst EI appeared to be preserved in FEM patients, neurocognition, and particularly processing speed, attention, and executive functions performance was already impaired at the early stages of the illness. Lower EIQ in FEM was associated with male sex and lower performance in verbal memory.

Although EI has been widely studied in patients in later stages of BD (Aparicio et al., Reference Aparicio, Santos, Jiménez-López, Bagney, Rodríguez-Jiménez and Sánchez-Morla2017; Frajo-Apor et al., Reference Frajo-Apor, Kemmler, Pardeller, Huber, Macina, Welte and Hofer2020; Samamé et al., Reference Samamé, Martino and Strejilevich2015; Varo et al., Reference Varo, Jiménez, Solé, Bonnín, Torrent, Lahera and Reinares2019), little is known about the EI performance of patients after a FEM and the course of EI impairment across the clinical stages of BD and the evidence is seldom conflicting. So far, only two studies assessed some level of EI patients after a FEM (Daros et al., Reference Daros, Ruocco, Reilly, Harris and Sweeney2014; Szmulewicz et al., Reference Szmulewicz, Lomastro, Valerio, Igoa and Martino2019). Nonetheless, these studies were characterized by small sample size, which limited the generalizability of results, and only evaluated the lower levels of EI abilities such as labeling, discrimination, and appraising emotions. Daros et al. assessed 24 non-affective FEP and 16 FEM patients in comparison with 35 HC both during acute psychosis and after 7 weeks of treatment (Daros et al., Reference Daros, Ruocco, Reilly, Harris and Sweeney2014). Both groups of patients presented difficulties recognizing facial expressions that did not resolve with treatment and clinical stabilization. In a small sample of 26 FEM patients, Szmulewicz et al. found that in comparison with HC, FEM patients presented a compromised cognitive theory of mind performance characterized by a reduced ability to infer intentions from others whilst the affective theory of mind performance was preserved, indicating that FEM patients were capable to detect other's emotions and feelings (Szmulewicz et al., Reference Szmulewicz, Lomastro, Valerio, Igoa and Martino2019). In the present study, FEM patients, in comparison with HC, did not present difficulties in EI, assessed through the full version of MSCEIT, which evaluates both lower and higher EI abilities.

Although EI appeared to be overall preserved among the patients after a FEM assessed in our study, their neurocognitive performance on processing speed, attention, and executive functions was mildly impaired. These findings are in line with a recent study assessing cognitive groups of patients after recovery from a FEM (Chakrabarty et al., Reference Chakrabarty, Torres, Su, Sawatzky, Keramatian and Yatham2021). The authors identified that almost the 50% of FEM patients reported selective cognitive impairment after recovery, with pronounced deficits in processing speed and lower performance in verbal memory, working memory, and executive functioning in comparison with HC. Furthermore, in line with our results, these deficits seemed to be stable over time in those patients that experienced a recurrence. Particularly, Kozicky et al. (Reference Kozicky, Torres, Silveira, Bond, Lam and Yatham2014) found that this impairment in cognitive performance was mostly evident in those who experienced longer manic or hypomanic episodes (Kozicky et al., Reference Kozicky, Torres, Silveira, Bond, Lam and Yatham2014).

Patients suffering from chronic BD, included in this study, presented impairment in all the cognitive domains and lower EIQ and difficulties in the MSCEIT understanding emotions branch. Our results are in line with previous studies, supporting the presence of less severe impairment in SC compared to neurocognitive domains in patients with BD (Bilderbeck et al., Reference Bilderbeck, Reed, McMahon, Atkinson, Price, Geddes and Harmer2016). Deficits of EI were not observed in FEM patients. This might suggest that more severe SC deficits might be associated with other conditions, such as schizophrenia, instead of BD since in non-affective FEP patients EI impairment was found to start early in the course of illness and to remain stable (Green et al., Reference Green, Bearden, Cannon, Fiske, Hellemann, Horan and Nuechterlein2012). Given that EI is more severely affected in psychosis than in mania, one may argue that patients reporting psychotic symptoms during the first episode of mania might show greater difficulties in EI than patients without psychotic symptoms. Despite this, we did not find any difference in terms of EIQ between FEM patients who presented psychotic symptoms at onset and those who did not. Our findings suggest that neurocognition seemed to be already altered at the first symptomatic manic presentation, whilst EI started out intact in the FEM patients and then slightly worsened with illness course. One recurring question is whether neurocognition and SC in BD are sufficiently distinct to be considered separately. Previous studies investigating the relationship between neurocognition and EI have yielded mixed and inconclusive results. While there are studies that reported that lower levels of EI may be mediated by neurocognitive abilities (Aparicio et al., Reference Aparicio, Santos, Jiménez-López, Bagney, Rodríguez-Jiménez and Sánchez-Morla2017; Frajo-Apor et al., Reference Frajo-Apor, Kemmler, Pardeller, Plass, Mühlbacher, Welte and Hofer2017), others have not found a relationship between the two constructs (Fanning, Bell, & Fiszdon, Reference Fanning, Bell and Fiszdon2012). Our results highlight the connection between EI and neurocognition and the idea that they are two complementary but separated constructs (DeTore, Mueser, & McGurk, Reference DeTore, Mueser and McGurk2018), with partial overlap and with a different degree of impairment. Thus, our findings were in line with many other works supporting the idea that neurocognitive ability may represent a ‘necessary, but not sufficient’ prerequisite for social cognitive abilities, especially in those that contain an emotional component (Bora, Veznedaroğlu, & Vahip, Reference Bora, Veznedaroğlu and Vahip2016; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Altshuler, Glahn, Miklowitz, Ochsner and Green2013; Varo et al., Reference Varo, Jiménez, Solé, Bonnín, Torrent, Lahera and Reinares2019). This view is consistent with studies from neuroimaging in social neuroscience (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2008). Nonetheless, the role of neurocognitive impairments on SC and EI in euthymic BD patients remains somewhat unclear. Therefore, the nature of this association should be the focus of further investigation.

Whilst in the present study the two groups of patients did not differ in terms of severity of symptoms at the time of evaluation, BD group performed worse than FEM group in measures of indicators assessing the burden of disease, such as longer duration of illness and higher total number of lifetime episodes, psychosocial functioning, and in the neurocognitive performance. Thus, our findings support the hypotheses that EI difficulties might be a result of the burden of disease and neurocognitive decline associated with the chronicity of the illness.

As for the socio-demographic, neurocognitive, and clinical variables associated with EIQ in patients after a FEM, lower EIQ scores were found to be associated with male sex and lower verbal memory performance. Regarding sex differences in EI, our findings are in line with previous studies in which men performed worse than women on EI in non-clinical samples (Pardeller, Frajo-Apor, Kemmler, & Hofer, Reference Pardeller, Frajo-Apor, Kemmler and Hofer2017) and BD patients (Varo et al., Reference Varo, Jiménez, Solé, Bonnín, Torrent, Lahera and Reinares2019). As for the role played by verbal memory in EI, our finding is in line with previous literature underlining how EI performance might be associated with cognitive abilities (Eack et al., Reference Eack, Greeno, Pogue-Geile, Newhill, Hogarty and Keshavan2010; Frajo-Apor et al., Reference Frajo-Apor, Kemmler, Pardeller, Huber, Macina, Welte and Hofer2020; Varo et al., Reference Varo, Jiménez, Solé, Bonnín, Torrent, Lahera and Reinares2019). In a previous study assessing BD patients, all neurocognitive domains were associated with EI (Varo et al., Reference Varo, Jiménez, Solé, Bonnín, Torrent, Lahera and Reinares2019). However, to date, it is difficult to ascertain which neuropsychological domain (among verbal memory, executive functions, psychomotor speed, working memory and attention) has a greater influence on SC, especially on EI. In the current study, verbal memory resulted to be the central domain involved in EI ability. EI was assessed by MSCEIT which demands an accurate interpretation of the semantic meaning of the social situation. It involves exercises related to verbal memory skills, such as association, categorization, and mental imagery. In another study assessing EI and cognitive abilities in healthy adults, verbal fluency was the only cognitive domain associated with EIQ (Pardeller et al., Reference Pardeller, Frajo-Apor, Kemmler and Hofer2017).

In the present study, being men with worse performance in verbal memory arose as risk factors for worse EI ability. In consequence, an exhaustive assessment of SC and EI in this population would be recommended in order to tailor specific early intervention strategies (Vieta et al., Reference Vieta, Salagre, Grande, Carvalho, Fernandes, Berk and Suppes2018).

The findings of the present study should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, since our study used data from two separate projects, the groups were not matched and there were uneven sample sizes. Moreover, some inclusion criteria differ between studies. In order to partially overcome this limitation, we decided to add age and both depressive and manic subsyndromal symptoms as covariates in the statistical models. Second, the cross-sectional design of this study did not enable us to determine causal inferences between EI, clinical symptomatology, and neurocognition, nor to examine the changes in EI ability associated with neuroprogression in BD. Since the FEM sample size was derived from a longitudinal study, we will be able to provide insight on the course of EI in the early phases of BD, for the patients included in the present study, as soon as the follow-up will be ended. Similarly, the description of influence of treatment should be further detailed. Also, the ability of MSCEIT test to discriminate individuals at the mean and high level of EI has been questioned (Fiori et al., Reference Fiori, Antonietti, Mikolajczak, Luminet, Hansenne and Rossier2014).

Despite these limitations, the strength of the present study is to provide insight on EI in patients in the early stage of the illness, an almost unexplored aspect in this group of patients and is the first investigation aimed at understanding which socio-demographic, clinical, and neurocognitive factors may contribute to EI levels in the early stages of BD. Furthermore, the present study can rely on a quite big sample size for both FEM and BD patients, allowing for a cross-sectional comparison of the EI abilities in two different phases of BD using the four branches of MSCEIT. In particular, BD patients have difficulties in EI but not patients that experienced their FEM over last 3 years. Therefore, our findings suggest that EI is preserved in early stages, which represents an optimistic result. However, this might worsen in later stages of the disease. Difficulties in EI performance might be possibly associated with the increasing burden of disease, and neuroprogression in chronic BD, although this hypothesis will need to be confirmed in longitudinal studies. On the contrary, neurocognition and psychosocial functioning seemed to be impaired at an earlier stage than EI. These findings have important implications in terms of early interventions, which should address not only neurocognitive performance but also social cognitive functioning at the early stages in order to prevent or mitigate the cognitive decline often associated with BD in the long-term (Vieta et al., Reference Vieta, Salagre, Grande, Carvalho, Fernandes, Berk and Suppes2018). Both EI and neurocognitive performance should be assessed in the early stages of the disease. While neurocognitive performance could be already impaired in the early stages and thus represents a target of secondary preventive intervention, EI could be not impaired in the early stages of the disease and should be addressed with primary preventive interventions aimed at possibly avoiding EI difficulties in these patients.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721005122

Data

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation; the CIBER of Mental Health (CIBERSAM); the Secretaria d'Universitats i Recerca del Departament d'Economia i Coneixement (2017 SGR 1365; 2017-SGR-1271) and the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya. This work has been also supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities integrated into the Plan Nacional de I + D + I y cofinanciado por el ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y el Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) through a ‘Miguel Servet’ postdoctoral contract (CPI14/00175 to CT), a Miguel Servet II contract (CPII19/00018 to CT, CPII16/00018 to EP-C), a ‘Rıo Hortega’ contract (CM19/00123 to ES), a ‘Sara Borrell’ (CD20/00177 to SA), both co-funded by European Social Fund ‘Investing in your future’, and the FIS grants (PI15/00283 and PI18/00805 to EV, PI15/00330 and PI18/00789 to AMA, PI18/01001 to IP). This work has been also supported by the PERIS projects SLT006/17/00357 and SLT006/17/00345 in the ‘Pla estrategic de Recerca i Innovacio en Salut 2016–2020’ (Health Department) and by the BITRECS project to NV, which has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 754550 and from ‘La Caixa’ Foundation (ID 100010434), under the agreement LCF/PR/GN18/50310006. In addition, it has been supported by ANID-PIA-ACT192064, ANID-FONDECYT 1180358, 1200601, Clínica Alemana de Santiago ID 863 to Juan Undurraga. The authors are extremely grateful to all the participants.

Financial support

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

EV has received grants and served as consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities (unrelated to the present work): AB-Biotics, Abbott, Allergan, Angelini, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, and Takeda. AMA has received funding for research projects and/or honoraria as a consultant or speaker for the following companies and institutions (work unrelated to the topic of this manuscript): Otsuka, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III. AB has received grants and served as a consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities in the last 5 years (unrelated to the present work): Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Pfizer. PAS has been a consultant to and/or has received honoraria or grants from Adamed, CIBERSAM, European Commission, Government of the Principality of Asturias, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Plan Nacional sobre Drogas, and Servier. MPGP has been a consultant to and/or has received honoraria/grants from Angelini, Alianza Otsuka-Lundbeck, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, and SAGE Therapeutics. IP has received CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from ADAMED, Janssen-Cilag, and Lundbeck. CGR has received honoraria/travel support from Angelini, Adamed, Janssen-Cilag, and Lundbeck. NV has received financial support for CME activities and travel funds from the following entities (unrelated to the present work): Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka. The rest of authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest related to the present article.