In the final analysis, our world is ruled by ideas – rational and ethical – and not by vested interests. The power of the idea, the particular weapon of scientists, moralists and concerned citizens, must prove of decisive importance in constructing a fairer and more peaceful world.Footnote 1

If every thinker is ultimately a local thinker, our Tinbergen story must start in The Hague. It was in April 1903, the month of Jan Tinbergen’s birth, that Andrew Carnegie ordered his banker to send the sum of $1.5 million to a representative of the Dutch government. It was a gift intended for the construction of a Peace Palace, or in Dutch, the Vredespaleis. The Peace Palace was only a small walk across the park from Tinbergen’s parental home. The Palace opened the year that Jan turned ten, 1913. Its construction had taken seven long years (Figure 1.1). But it turned The Hague into “the capital of the United States of the World,” as one, perhaps overly enthusiastic, commentator wrote.

Figure 1.1 The Peace Palace under construction in The Hague, 1911.

1.1 High Hopes

The Vredespaleis was the crowning achievement of a series of events in The Hague that slowly transformed it into a center of global affairs, something it remains to this day. Currently, the city is home to the International Court of Justice, as well as the International Criminal Court and a host of other international legal organizations and United Nations offices. This history of The Hague as an international city starts in the late nineteenth century, when after a successful international conference on private law in 1893, The Hague was chosen as the location of the first Peace Conference in 1899. The initiative for this new type of international conference was taken by one of the least likely candidates, a representative of the final generation of imperialists, Tsar Nicolas II of Russia. He had extended invitations to all European countries, the United States, and Mexico as well as four Asian countries: Japan, Siam, Persia, and China. To everyone’s surprise, all countries accepted.

The 1899 conference lasted two whole months, was held in the royal Huis ten Bosch, and was presided over by the Dutch Queen, Wilhelmina. The imperial leaders of Germany and the United Kingdom were skeptical of the whole undertaking and suspicious about the true political goals of the Tsar. But the burgeoning pacifist movement saw the conference and its official aims as an enormous opportunity. Under the spiritual guidance of Bertha von Suttner, whose novel Lay Down Your Arms of 1889 marked an important milestone in the pacifist movement, they put serious pressure on the gathered officials. Diplomatically, the conference proved a great success and resulted in the first multilateral agreement of its kind, an agreement that included the founding of the International Court of Arbitrage, which for the first decade of its existence was housed in the city center of The Hague. This supranational court could arbitrate in international conflicts through binding rulings, although the involved countries had to accept that the case be brought before the Court. But the pacifist movement was deeply disappointed that the first conference made no significant steps in the direction of its most important aim: disarmament.

Another, unintended, consequence was that the 1899 conference brought many social organizations, intellectuals, and journalists of a pacifist bent from all over the world to The Hague.Footnote 2 The delegates of various countries, some of them idealistic politicians, were quite willing to listen to the peace activists gathered in the city. In particular, the American delegates were impressed with the spirit surrounding the conference. Two among them, Frederic W. Holls and Andrew White, would encourage their friend Andrew Carnegie in the following years to support the cause of international peace. Carnegie, who had a particular fondness for libraries, of which he funded no fewer than 3,000 in his life, was soon convinced that he could help finance a comprehensive library on international law. But Holls and White were out for more than just a library, and in the end persuaded Carnegie that something bigger than a library was possible. This resulted in the plan to build a center that would house both the library and the international court. It was for this purpose that Carnegie transferred the $1.5 million in 1903. After much deliberation, an architectural design was agreed on in 1907, the same year that the second international Peace Conference was held, this time in the geographical heart of Dutch politics and the seat of the Dutch parliament, the Binnenhof. During this four-month conference there was a ceremony for the official laying of the first stone.Footnote 3

It would take another six years before the Vredespaleis was officially opened. On the opening of the Vredespaleis, the Dutch society “Peace through Law” (Vrede door Recht) described the Peace Palace as “the symbol of the near future, in which international law rules, and thereby simultaneously serves the interests of all peoples.”Footnote 4 The German legal professor Walter Schücking described it as “a new age in world history, the age of the organization of the World.”Footnote 5 They were lofty words written in an age in which violent international conflict was the norm, and in all honesty that would remain so for the next few decades. Yet in the eyes of many of the age, the Vredespaleis was a symbol not just of the increased economic integration of the world in the years leading up to World War I – what has been called the first wave of globalization – but also of the growing sense that the twentieth century required a different world order than the nineteenth-century empires. For the enthusiasts, the Peace Temple, as they sometimes called it, symbolized the increased rationality in international politics that would one day lead to a world without war.

1.2 Naïve Utopianism

The Vredespaleis came about as a combination of state initiative, private philanthropy, and civil society activism; Tsar Nicolas II, the most old-fashioned Imperial leader, had brought the states together; Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate, had donated the money; and its realization reflected both the emergence and the activism of an international civil society.

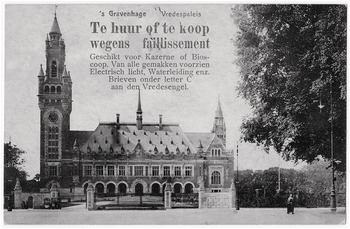

It is hard, however, to look at this new spirt of international collaboration without a healthy dose of skepticism. Just after the 1899 conference concluded, the second Boer War broke out in South Africa, a typical imperial conflict. And over the coming decade a variety of international conflicts continued to plague both Europe and Asia. The new International Court of Arbitrage handled four cases during the period between the first and the second Peace Conference, and eight more before World War I broke out. It was a mere fraction of the number of international conflicts of the period. It did not take long after the opening before satirical postcards appeared that declared the bankruptcy of the Vredespaleis and offered it to the highest bidder (Figure 1.2). The postcards were inspired by a short play written by the Herman Heijermans in which the main character was an auctioneer who tries to sell this “gentleman’s home,” but to no avail: “[N]obody wants it, so now we’re stuck with it.”

Figure 1.2 Satirical postcard that suggested the Peace Palace was bankrupt, and could be repurposed as cinema. Interested bidders could address their letters to the Angel of Peace, C. (for Carnegie).

Politically too, there were disappointments. Attempts at the Second Conference to make the use of the International Court of Arbitrage obligatory in the case of an international conflict failed because it was opposed by some of the imperial powers. The conferences certainly had not measured up to the expectations of those in the pacifist movement. But this did not prevent the movement from gaining more momentum. Bertha von Suttner had been in contact with Alfred Nobel, and that might have been one of the reasons why the Nobel Prizes included one for peace. She was the first female laureate in 1905.

Even so, peace movement did not find widespread acceptance. From the socialist side many mocking voices could be heard about the Peace Conference between the imperial powers, and the hopes for peace under imperial capitalism more generally. For them it was clear that only a more fundamental overhaul of the capitalist system with its imperialist tendencies could bring about peace. It was thus not hard to simply dismiss the Vredespaleis as at best a naïve Utopian project, and perhaps nothing more than a plaything of the rich and powerful. Even its opening had missed much of the international allure of the previous conferences: Andrew Carnegie and the Dutch Royal Family were present, as were a host of international law professors, but few foreign governments had sent a delegation.Footnote 6 It seemed that The Hague was indeed stuck with the Vredespaleis.

If a skeptic wanted any evidence that the Vredespaleis project was little more than a cover-up for imperialist aspirations, they only had to point to its design. Andrew Carnegie had requested that the architectural design contest should be open, but the committee that oversaw the competition consisted of relatively conservative architectural experts who insisted that designs be solicited from a list of renowned architects (who also would receive a higher fee if their design won). When the jury announced the winner, Louis Cordonnier, an able but conservative architect who had submitted an almost baroque proposal, there was a general outcry in the press. The general opinion was that the Vredespaleis deserved an architectural design that fitted its aspirational, forward-looking spirit.

There had been several progressive submissions, such as those of Otto Wagner, the Viennese avant-garde architect, and the even more daring futuristic design of Eero Saarinen, a Finnish architect, which enjoyed the admiration of a few jury members. Instead, the winning design was by an architect of one of the imperial powers on the world stage, in a style that reflected Old World grandeur. It symbolized the tension at the heart of the whole endeavor: Were the old imperial powers trying to accommodate some of the social pressure through this whole project, or did they really aspire to the construction of a new type of world order?

It was a question that could also be asked about the Peace Conferences themselves. Were they not merely a continuation by the Great Powers to maintain and strengthen existing power positions? Or did they reflect the start of a new era in international politics? Were the peace conferences merely a modern version of an old tune, the final symphonies of the Concert of Europe? Or did they represent a new type of music altogether?

1.3 Tinbergen’s The Hague

To many the answer was clear as day: of course, this building and not just its architecture was nothing more than a façade. But it is unlikely that Tinbergen would have seen it like that. Tinbergen worked in the realm of possibilities. To him, though the peace palace did not lead to disarmament or world peace, it still embodied a vision, a hope for a better future. Although it might not have been the bringer of peace, it was certainly a model of what the world could become. It was this perspective that would become central in Tinbergen’s work. His perspective was idealistic and often ignored whether something was politically feasible in the short run. He preferred to offer a vision that could guide present efforts and give a sense of direction. Even his famous mathematical models of the economy, which were designed to be practically useful, offered not primarily a description of what the world already was, or what it would become if current trends persisted, but rather what the world could become. The Peace Palace, if anything, symbolized possibilities, not realities.

And in its favor, the location was not badly chosen at all. After all, The Hague is the seat of the government of the Netherlands, a small open country that owes its existence to successful (and peaceful) relations with its much bigger neighbors. It is now considered a natural home for international institutions. Much like Geneva in Switzerland or Brussels in Belgium, it is a medium-sized city in a small country, which is acutely aware of the dangers and costs of international conflict. As centers of governance of small nations, they have much to gain from international cooperation, if only because much of what they seek to realize cannot happen without the cooperation of other nations. Or to put that sentiment into the language of power politics, it is unlikely that the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland could ever exert much direct influence over its large neighbors. Economically, too, these cities and their host countries are completely dependent on trade with the rest of the world, and trade requires friendly relationships and preferably open trading routes. It was no coincidence that Hugo Grotius, the great legal scholar of international maritime law, was a Dutchman.

Cities like The Hague, and countries like the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Belgium often present themselves as neutral places that can act as arbiters in the international context. The three countries all have a long history of political neutrality. The Hague, moreover, is located close to the sea and is hence well connected to the rest of the world. As if to symbolize this connection, the Vredespaleis was built on the Scheveningsestraat, a street originally designed by Christiaan Huygens, the seventeenth-century natural scientist. It connects The Hague to Scheveningen, a small fishing and beach town, and the connection of The Hague to the sea and the rest of the world.

What is more, the Netherlands shares with Switzerland an interesting history of decentralization of power within a common structure, a history that in the Netherlands goes back to the days of the Dutch Republic of the Seven Provinces, founded in 1579. It is this type of federalism, decentralization within a common overarching structure, which was held up by the peace movement of 1900 as a model for world governance. It was not a world government that was their goal, but instead a shared legal (infra)structure, within which nation-states could retain (most of) their sovereignty. It was intent not on breaking the power of the nation-state, or even that of the Empires, but on the creation of a small set of shared rules for international security. It was a similar model that Tinbergen would uphold in 1945, and the same model that inspired the World Federalist Movement of which he was an active member until his death in 1994. It is not a federalism in which all local sovereignty is lost, and the world becomes one, but instead a decentralized form of governance within a federalist structure. That structure would provide a set of general rules to which all countries were bound.

For the pacifists of 1900 it was believed that the law, or rather, international law, could provide this kind of ordering, and to this day The Hague is known as the city of international law. Their slogan was “Peace through Law.” The intellectual symbol for this Dutch tradition is Hugo de Groot, or Grotius. His seventeenth-century works were some of the first that considered the possibility of international law, especially international law at sea, efforts in which he was joined by Cornelis van Bijnkershoek (who died in The Hague). A statue of Grotius was installed in the Vredespaleis to mark that this endeavor was to be a continuation of his project of international law. The Hague, not otherwise known as a great intellectual center (it is the largest city in the Netherlands without a university), was enriched by the library of international law. It is this tradition that was continued in the International Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, aimed at international cooperation and founded in 1952; from its start Tinbergen was deeply engaged with it.

Jan Tinbergen is now often remembered for his work in econometrics and as a pioneer in the practice of modeling in economics. But that is to miss the greater significance of his work, and most importantly his own aspirations. It is remarkable how many of the features that characterize The Hague – the internationalism and the focus on legal order as well as governance – are central to Tinbergen’s work and life. For starters, he was a lifelong proponent of international organizations and he worked for many of them, including the League of Nations and the United Nations. And although it is undeniable that he was a quantitative economist who lived by Kelvin’s dictum that “if one cannot measure something, our knowledge of it is only meagre and unsatisfactory,” it is surprising how much of his work is about institutional and policy design. His deep institutional awareness stands out in the modern discipline of economics, which has typically treated them as background material. The idea that in order for an economy to function it has to be ordered is central to Tinbergen’s work but strangely absent from most reflections on his work.

This omission has also meant that the literature on Tinbergen has too easily accepted the idea that took firm root after he won the first Nobel Prize in Economics, that he was one of the founders of the field. It is undeniable that he was one of the pioneers of econometrics, the combination of measurement, modeling, and economic theory that is the foundation of macroeconomic models to this day. But Tinbergen continued a nineteenth-century tradition of economics, which believed that it was one of the sciences in service of the state. This was directly at odds with the dominant trend of the time, which had started with the marginal revolution, which sought to turn economics into an autonomous scientific discipline, modeled after physics.

Not only did Tinbergen work in service of the state at the bureau of statistics, the planning bureau, and at various international political organizations. He also made sure that the knowledge he produced could be used by the modern state, in particular, in expert organizations that advised governments. His approach is far more deeply rooted in the nineteenth century and the German tradition of Kameralwissenschaften and Staatswissenschaften than is often acknowledged. And it was therefore no coincidence that during his long career he was often caught between his own ideals and the political goals of the governments he was serving. He hoped that the modern scientific methods he promoted for the design of policy represented a way to rationalize politics, and the state more generally. But there was always the danger that these same methods were used for quite different purposes: the continuation of conflict and imperialism as it had been practiced in the nineteenth century. This was perhaps nowhere more evident than in his work on development economics where he was constantly caught between international power politics and his own efforts to improve the economic situation in the underdeveloped parts of the world.

1.4 The Organization of Peace and Economic Prosperity

Tinbergen’s work points the way forward to modern economics in which both model-building and quantitative economics in the form of econometrics are central, but it also represents an older legal understanding of the economy. In that legal understanding the crucial distinction is not between equilibrium and disequilibrium or growth and a recession as it is in economics, but rather between social order and disorder or conflict. In his perspective the threat of war was never far away. Peace, both internal peace between social classes and external peace organized through international law and organizations, was a precondition for economic prosperity. Tinbergen more than many of his fellow economists has been concerned with issues of international governance and security. After his retirement he wrote extensively on these subjects, for example, in Welfare and Warfare. But he was intimately concerned with them as early as 1945Footnote 7 and was one of the first economists to explore the consequences of economic integration, in the context of the emergence of the European Union and other such organizations in his work of the 1940s and 1950s. His convergence theory explores how the institutional orders of the East (under socialism) and the West (under capitalism) are slowly growing toward each other.

In his work, this institutional and legal focus takes the form not of legal analysis directly, but rather of the institutional design of the economy. The fact that he worked through so many organizations, from the League of Nations to the UN, the Central Planning Bureau, and the Social-Economic Council in the Netherlands, is no coincidence but central to his understanding of how a peaceful, that is, stable economy can be ordered and constructed.

This project started with the 1930s’ attempts to stabilize the Dutch economy in the midst of the Great Depression, and remained with him until his very last work on the “optimal economic order.” As such, Tinbergen’s work was rooted in an older historical and legal approach, characteristic of the nineteenth century. And at the same time his constructivist vision of the economy (the belief in Machbarkeit) and his preference for mathematical and quantitative models were unquestionably modern. Most secondary accounts about Tinbergen have emphasized the modern nature of his economics. But his contributions literally mark the break between the nineteenth century and the twentieth century, much like the period leading up to World War I, in which the Vredespaleis was constructed, represented the break between the imperial nineteenth-century international order and the nationalist and internationalist order of the twentieth century. Together with Ragnar Frisch, the Norwegian econometrician with whom he shared the Nobel Prize, he is presented as the father of econometrics and macroeconomic modeling and a pioneer in development economics. But that obscures that Tinbergen’s thought was far broader, and crucially shaped by his thinking in terms of legal and institutional orders that support the economy. He used that insight to modernize the economy, but the insight itself was historical and institutional. It belonged to an older, nineteenth-century approach to economics that emphasized law and historical development.

That tension is visible in other aspects of his work. Although he was in contact with the leading physicists of the age, including Albert Einstein, he remained wedded to a nineteenth-century belief in determinism – not completely unlike Einstein himself. But it is mostly the optimism of his work that is also thoroughly of the nineteenth century, for Tinbergen the line of history is upward. The path toward modernity that the West has traveled has to be perfected in a mature socialism, free of dogma, he argued.Footnote 8 And this ideal was universal and should be expanded to the rest of the world. Tinbergen was a pacifist and weary of imperialism, much like the pacifists who invigorated the internationalist spirit of the Vredespaleis. But their vision was still wedded to a modernist perspective that took the expansion of Western civilization across the planet as the natural and ultimate goal. The means of doing so could no longer be imperial, but the fundamental goal had not changed. In Tinbergen’s work the means become development economics; his goals remained modernist and universalist.

I will argue that Tinbergen’s greatest contribution to this project is not a particular theory that explains or helps us understand the world, but instead is a theory and technique of governance. The core of his work is a technique for policymaking and an institutional design through which that technique could be effective. Tinbergen is never primarily concerned with how to explain the world; the goal is always to improve it. His theory of governance connects what we know about the dynamics of the economy to the theory of how we would like the world to be. If science is about what the world is, and politics about what the world could be, then we should situate Tinbergen’s most important contribution precisely at the intersection. It shows the politicians how they can achieve what they hope to achieve, and it shows the scientists how their knowledge can be put to use. It was, so to speak, the institutional legwork that allowed the knowledge of the library of the Peace Palace to be put to practical use. If politics is the art of the possible, then Tinbergen’s economics is the exploration of the possible.

More than once his work has been called naïve or overly optimistic, charges that anyone associated with the Vredespaleis will instantly recognize. But they will also realize that such charges are at least partly off the mark – nobody had ever suggested that international peace was easy or even attainable within a generation. Tinbergen himself would, late in his life, capture it clearly – he was not optimistic, but he was hopeful.

The deep tension between the lofty ideals embodied by the Vredespaleis and the political reality of its time is mirrored in the life of Tinbergen. In his oeuvre we find plenty of these lofty ideals: a more integrated and peaceful economy, the convergence between the East and the West, the economic development of the Global South, and a more just and equal economic order in the West. But his work spans the turbulent political-economic reality of the twentieth century. It involves many compromises on his side. This is all too apparent as he moves from the idealistic cultural socialism of his youth to the polarized political reality of the 1930s and the mostly failed attempts to do something about the Great Depression; as he attempts to navigate the Central Bureau of Statistics through World War II without getting in trouble with the German occupiers, and without helping them too much; as he attempts to set up neutral economic expertise institutions in the Netherlands, which rise above party lines, at the expense of his own political-economic ideals; as he attempts to plan economic development of the newly sovereign countries around the world such as India or Turkey, where he has to cope with the military generals and internal political conflicts; as he attempts to argue for convergence of the East and the West amid the hardening of the Cold War; as he attempts to convince governments around the world of their global responsibilities, while national interests seem to trump more idealistic goals time and again; and as he attempts to put on the agenda the environmental threats facing humanity late in his career.

The balancing act he faced is not merely one between ideals and political realities. It is also a human tension. Tinbergen’s most successful political student, Jan Pronk, minister of development aid and adjunct-secretary at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), once said that God is required, humanism is not enough. Ultimately, the Heidelberger Catechism, one of the foundational documents of German and Dutch Protestantism, is correct: “Man is ultimately flawed, that is the decisive human condition.”Footnote 9 He and Tinbergen shared this particular Protestant view, and drew from it the conclusion that rules were required. In the form of law and institutions, but also in the form of cultural norms. The OrdnungFootnote 10 Tinbergen sought to create both nationally and internationally was meant to prevent the worst from happening. Models of how the world might be were necessary to provide hope and guidance. But it was a second-best option; perfection is not attainable for humans.Footnote 11

His economics thus comes about as a response to the conflict and instability in the world. His macroeconometric model, the first one in the world, is primarily an outcome of the efforts to present a way out of the crisis not tainted by ideological dogma. His theory of economic policy is an outcome of his activities at the Central Planning Bureau, a new organization of economic expertise that becomes an important part of economic policymaking in the Netherlands. His theory of planning in stages is developed in his efforts to boost economic growth in India, Turkey, and elsewhere. His convergence theory cannot be disconnected from his attempts to maintain a dialogue across the Iron Curtain. His work in international trade and order is often written as a direct response to real-world developments in those areas and his activities at the United Nations. The measurement of human welfare he tries to develop is intimately tied up in his efforts to provide a scientific definition of equality.

His efforts are frequently frustrated and fruitless, as such efforts often are. World War I broke out only one year after the Vredespaleis opened. But then again, just a few years before his death in 1994, the Iron Curtain came down and Michael Gorbachev, Prime Minister of Russia, paid him a personal visit to thank him for his hopeful work on the convergence of the East and the West. Planning, perhaps the central word in Tinbergen’s vocabulary, had little do with the downfall of communism. Nonetheless, he had worked toward it, he had hoped for it, he had believed it was possible. His final manuscript dealt with the subject of an optimal world order. No, the Vredespaleis did not bring peace, but it believed in it.

The text of the guided tour written in 1914 by the civil engineer J. A. G. van der Steur, who oversaw the construction of the Vredespaleis, concluded that this building is “Special, for from it one can hear a calling from the future; a calling easily mocked in this era of war and violence, but one that manages to rise above the mockery, when one realizes that the Vredespaleis is not a palace of the Peace, ready to provide a home for it, as if Peace had already conquered the world, it is a palace for the Peace, ready to symbolize all of the power which emanates just from her spirit alone.”Footnote 12 Tinbergen’s work is not a palace where a just economy is realized, where the blueprint for a stable international economy can be found, but it is a palace for an economy realizing socialist ideals, a palace for the construction of an international order. That project would take him to Leiden where he became a scientist; to Geneva where he contributed to the League of Nations;, to Ankara, New Delhi, Jakarta, Cairo, and other capitals of the new world where he shaped development economics in practice; to New York for the United Nations headquarters and the agenda of Development Decade II (1970–80); to Rome where he sought to continue the work of the people behind the famous environmental Club of Rome report; to Stockholm where he was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Economics; and to the Soviet Union where he sought to create a dialogue between East and West. But the project was fundamentally shaped in outlook and ideals in his place of birth The Hague; for Tinbergen, home was the ultimate place of peace.