Introduction

Leprosy, a neglected tropical disease (NTD) mainly characterised by skin lesions and damage to peripheral nerves, is estimated to have a burden of disease of around 21100 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) (Kyu et al., Reference Kyu, Abate, Abate, Abay, Abbafati, Abbasi, Abbastabar, Abd-Allah, Abdela and Abdelalim2018). However, until now, quantification of the burden of leprosy has taken a very narrow view, including only the number of new cases in a given year and the proportion among these that have visible – so-called ‘grade 2’ – disabilities. Chronic consequences of leprosy, such as the negative impact on social participation and mental health, have not been taken into account due to data scarcity and the lack of standardised data collection (Jamison et al., Reference Jamison, Breman, Measham, Alleyne, Claeson, Evans, Jha, Mills and Musgrove2006; Hotez et al., Reference Hotez, Alvarado, Basáñez, Bolliger, Bourne, Boussinesq, Brooker, Brown, Buckle and Budke2014). In addition, leprosy develops progressively at the onset, but gradually over time. Quantifying the burden at one particular time is therefore not representative of the full disease course (Richardus, Reference Richardus2013). Moreover, leprosy does not only influence the lives of (former) patients, but also the lives of their direct contacts, such as family members, friends and people in their community. The disability rates that are used to calculate DALYs represent societal preferences for various health states, rather than experienced health of the persons coping with impairment and disability (Hotez et al., Reference Hotez, Alvarado, Basáñez, Bolliger, Bourne, Boussinesq, Brooker, Brown, Buckle and Budke2014). Taking the experienced health into account when calculating the burden of leprosy is essential, since leprosy can be demonstrated to have a significant impact on social participation and mental health in addition to causing physical impairments (Bainson and Van den Borne, Reference Bainson and Van Den Borne1998).

Bainson and Van den Borne (Reference Bainson and Van Den Borne1998) described the mental health effects of having leprosy. They found that leprosy follows both a biomedical and a social course. In the biomedical course, impairments caused by leprosy lead to emotional reactions and negative behaviours. In the social course, persons with leprosy encounter social barriers that lead to disability, emotional reactions and negative behaviours. Both the biomedical and the social trajectory can contribute to unemployment, economic and physical dependence and difficulty with social integration. This can lead to dehabilitation and consequently to destitution (Bainson and Van den Borne, Reference Bainson and Van Den Borne1998). Litt et al. (Reference Litt, Baker and Molyneux2012) further examined the relationship between NTDs, including leprosy, and mental health conditions. They found that the consequences of NTDs include stigma, social exclusion, reduced access to healthcare services, lack of educational and employment opportunities, restriction of rights, increased disability and early mortality. Each of these consequences may result in poor mental wellbeing by increasing feelings and behaviours such as sadness, hopelessness and social withdrawal. Poor mental wellbeing and other consequences of an NTD can both contribute to the development of mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depression (Litt et al., Reference Litt, Baker and Molyneux2012).

The psychological and societal consequences of leprosy have been widely researched, in particular in relation to disability and stigma (Cross and Choudhary, Reference Cross and Choudhary2005; Sermrittirong and Van Brakel, Reference Sermrittirong and Van Brakel2014). However, no systematic review had been done to consolidate the evidence regarding the specific impact of leprosy on mental health, including mental health conditions. Additionally, little is known about the impact of leprosy on family members who are indirectly affected. Therefore, the aim of this study is to review existing studies regarding mental health and leprosy in order to make an inventory of the ways in which leprosy impacts the mental health of people affected and their family members.

Methods

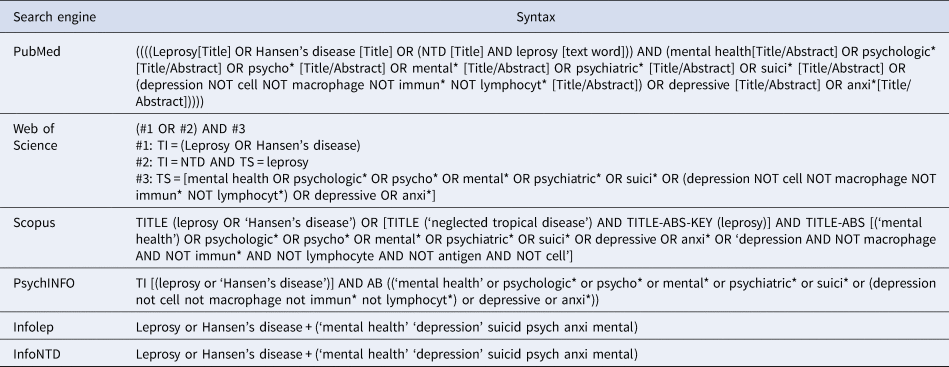

A systematic search was conducted in six online databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, Infolep and InfoNTD to identify relevant studies regarding the impact of leprosy on the mental health of those affected and their family members. A generic syntax was set up consisting of keywords found in articles that were used for orientation regarding the subject and articles suggested by leprosy experts. The keywords were: leprosy, Hansen's disease, NTD, mental disease, mental condition, mental health, psychologic, psychiatric, depression, anxiety and suicide. Variations of these keywords were also used to devise syntaxes for the various databases (see Table 1). In addition, other relevant studies and literature were found via Google Scholar and the ‘snowball method’ (bibliography screening of relevant articles for other relevant articles).

Table 1. Syntaxes for search

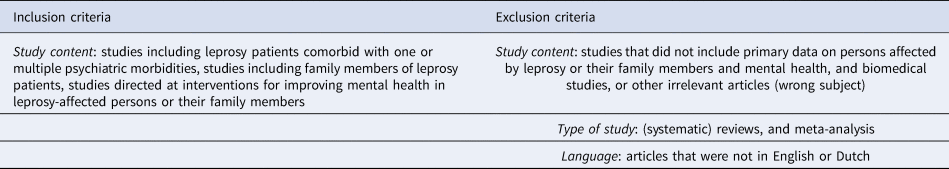

Studies were excluded from the search if they had a primarily biomedical character, were reviews or meta-analyses, were written in a language other than English or Dutch, portrayed the perspective of people other than persons affected by leprosy or their family members or were obviously irrelevant in any other way, for instance, having content with no relation to mental health. The final search was performed on 8 February 2018.

All articles identified in the search were exported in a reference manager (EndNote). Duplicates were automatically removed. The next step consisted of title and abstract screening. Irrelevant articles were excluded. Next, screening of full text articles was done. Both the first and second screening were performed by one author (PS) and supervised by two other authors (WvB, MW). Uncertainties regarding inclusion or relevance of data were resolved together with the second authors. The title, abstract and full-text screening were executed in Covidence, a web-based software platform that streamlines the production of systematic reviews. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to guide the screening process (see Table 2).

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

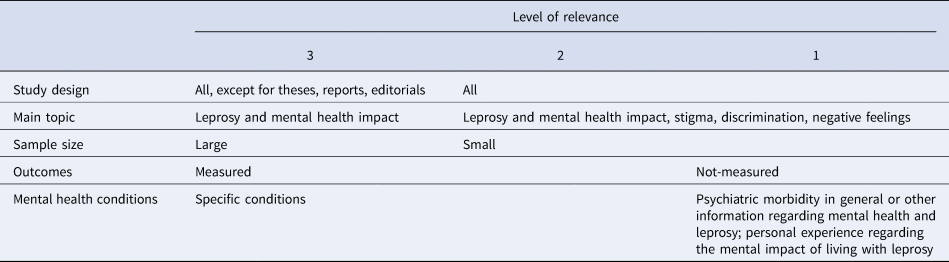

Data extraction was done in Excel. Relevant information including study characteristics, patient characteristics, morbidity specifics and outcomes was noted. The articles were labelled based on the relevance. The relevance of the articles was determined based on several characteristics (Table 3). Specific conditions, studies and other topics and themes were noted and results were combined, described and discussed based on similarities and discrepancies between these. Ranking the articles provided a critical view on how to report the results and what to report. The ranking was performed by PS and supervised by MW.

Table 3. Criteria of relevant articles

Results

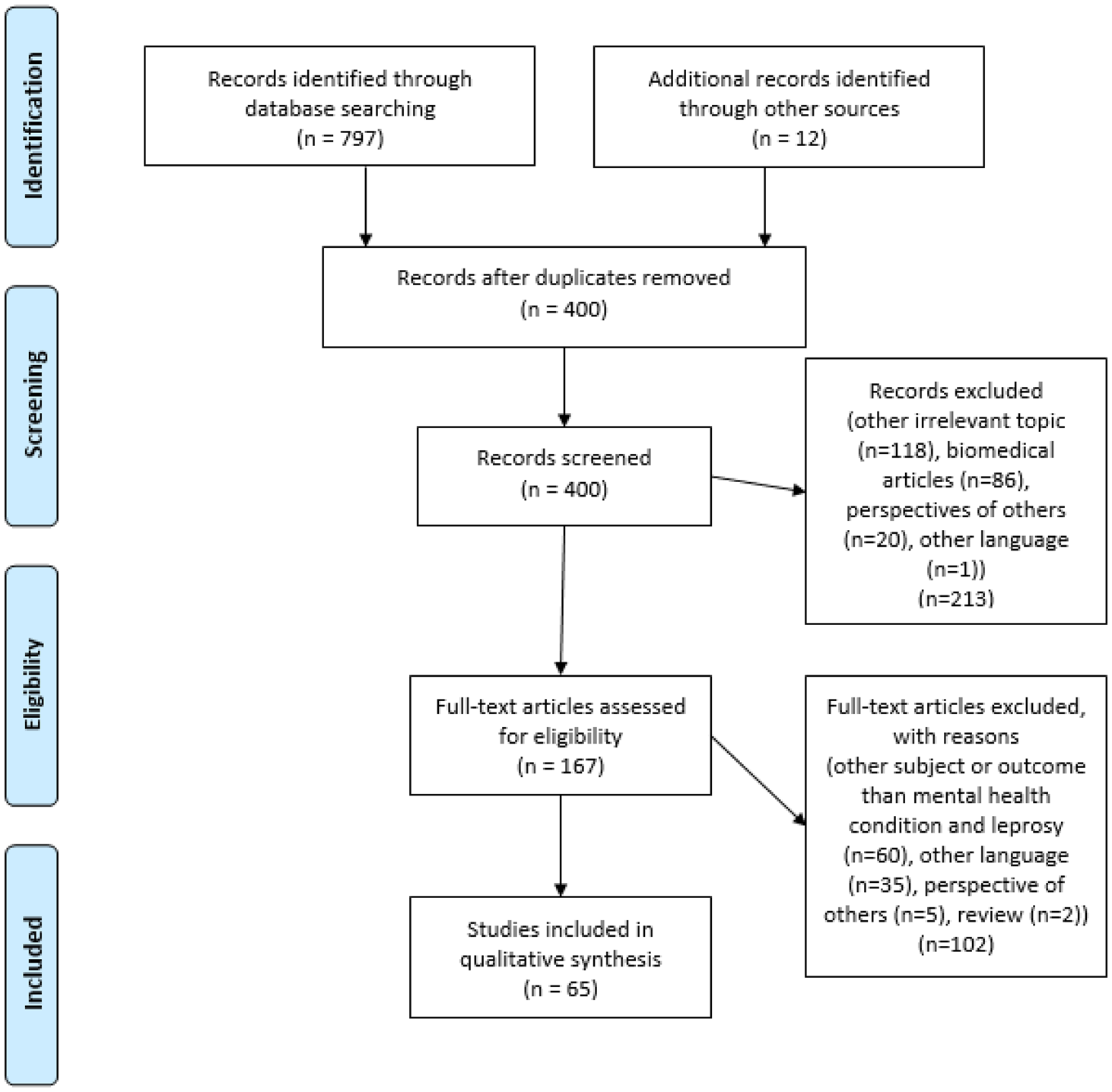

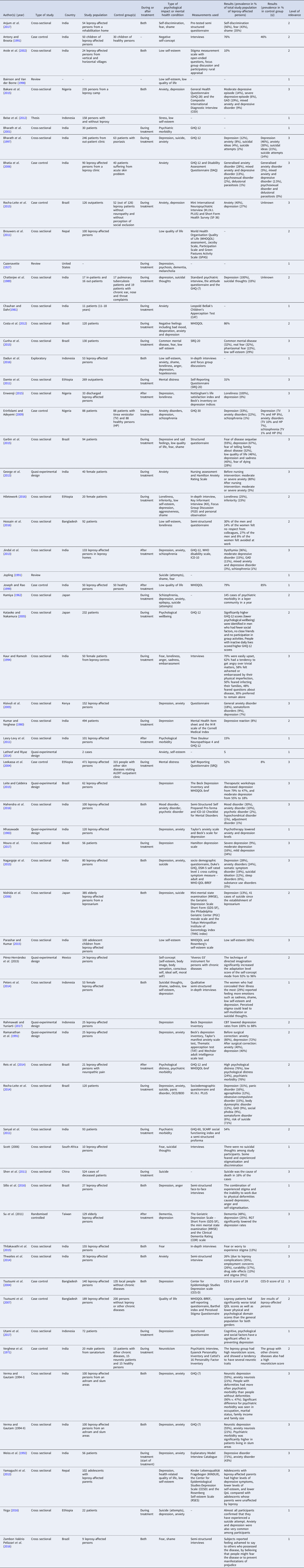

In total, 797 articles were found (see Fig. 1). In addition, 12 articles were found via Google Scholar or the ‘snowball method’ by using backwards reference searching and added to the study. Out of the 797 articles, 409 were removed as they were marked as duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, 213 studies were discarded based on the exclusion criteria: biomedical articles that described cellular processes of mental health or leprosy (n = 86), because they were otherwise irrelevant (n = 118), represented perspectives of others than leprosy-affected or their family members (n = 20) or articles in another language (n = 1). In addition, 20 duplicates were removed. A total of 167 studies were included for full text screening. Based on the above exclusion criteria, a further 102 articles were discarded at this stage: other subject or outcome than mental health condition and leprosy (n = 60), other language (n = 35), perspective of others (n = 5), review (n = 2). In the end, we included an analysis of 65 relevant articles regarding leprosy and mental health. Of these, 11 of 65 articles were studies describing interventions. Out of 65 studies, 62 concerned leprosy-affected persons, while three studies concerned the family members of the affected persons. The studies included and their important characteristics are presented in Table 4.

Fig. 1. Results in PRISMA flowchart.

Table 4. Articles included in review uploaded separately

Psychiatric morbidity

Out of the 65 articles, three articles described psychiatric morbidity in general among leprosy-affected persons. Psychiatric morbidity, or mental ill health, was measured with the general health questionnaire (GHQ). The GHQ is a tool for screening and identifying minor psychiatric conditions among adults (GL Assessment, Reference Gl Assessmentn.d.). There are various versions of the GHQ: GHQ-12, GHQ-28, GHQ-30 and GHQ-60. For the purpose of identifying psychiatric morbidity, the shorter test (GHQ-12) is just as effective as the longer tests (GHQ-28 and GHQ-30) (Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Gater, Sartorius, Ustun, Piccinelli, Gureje and Rutter1997). However, the longer tests are more suitable for thorough examinations (GL Assessment, Reference Gl Assessmentn.d.).

All GHQ-based studies identified that leprosy-affected persons scored highly on the GHQ, and thus are likely to have a high prevalence of psychiatric morbidity. Bharath et al. (Reference Bharath, Shamasundar, Raghuram and Subbakrishna2001) found that the mean GHQ-12 score of the leprosy patients in Bangalore, India was 5.43. Scores of 2 and higher are associated with psychiatric morbidity. Sanyal et al. (Reference Sanyal, Gupta, Mahapatra and Samanta2011) reported that more than the half of the leprosy-affected persons studied at a leprosy clinic in Kolkata, India, tested positive for psychiatric morbidity on the GHQ-60 (Sanyal et al., Reference Sanyal, Gupta, Mahapatra and Samanta2011).

Moreover, Bhatia et al. (Reference Bhatia, Chandra, Bhattacharya and Imran2006) compared the presence of psychiatric morbidity, measured with the GHQ-12, among leprosy-affected persons and healthy persons from Delhi, India. They found that leprosy-affected persons had a significantly higher prevalence of psychiatric morbidity (44.4%) than healthy persons (7.5%).

Depressive disorders

The most frequently identified psychiatric condition among leprosy patients is depression. Of the 27 articles that reported depression in combination with leprosy, the majority reported on the prevalence of depression. The prevalence of depression varied in different settings and countries. For example, a study from Kumar and Verghese (Reference Kumar and Verghese1980) investigated depression among almost 500 leprosy patients from Gudiyattam, India, and found a prevalence of 8.1%, whereas a study executed by Kisivuli et al. (Reference Kisivuli, Othieno, Mburu, Kathuku, Obondo and Nasokho2005) among 152 leprosy-affected persons in West Kenya found a prevalence of 49.4%. Weiss et al. (Reference Weiss, Doongaji, Siddhartha, Wypij, Pathare, Bhatawdekar, Bhave, Sheth and Fernandes1992) investigated the prevalence of depressive disorders among 56 leprosy patients from Mumbai who had recently started treatment and found a prevalence rate of 71%.

Additionally, several studies reported the severity or specific form of depression that was found among leprosy-affected persons. For instance, a recent study conducted by Moura et al. (Reference Moura, Aparecida, Grossi, Lehman, Salgado, Almeida and Rocha2017) researched the severity of depression among leprosy-affected persons in a referral hospital in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Out of 56 people, 19 had mild depression (34%), 9 had moderate depression (16%) and 5 had severe depression (8.9%), measured with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Also, Jindal et al. (Reference Jindal, Singh, Mohan and Mahajan2013) looked at types of depression. They found that among 133 Punjabi leprosy patients, 25.5% suffered from dysthymia, 15% had experienced a moderate depressive episode and 3% had experienced a mixed anxiety and depressive episode.

Moreover, a few studies compared prevalence of depression in leprosy-affected persons with that among healthy persons. Erinfolami and Adeyemi (Reference Erinfolami and Adeyemi2009) found that the prevalence among Nigerian leprosy-affected persons was significantly higher than in the healthy controls (respectively 35.2 and 8%). Studies by Nishida et al. (Reference Nishida, Nakamura and Aosaki2006) and Tsutsumi et al. (Reference Tsutsumi, Izutsu, Akramul Islam, Amed, Nakahara, Takagi and Wakai2004) also confirmed this result in their studies.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders were the second most frequently reported mental health condition, highlighted in 17 out of 65 articles. The prevalence of anxiety disorders among leprosy-affected persons ranged from 10% to 20%. The studies reported different types of anxiety disorders. For instance, Mahendra et al. (Reference Mahendra, Yaduvanshi, Sharma, Ali, Rathore and Kuchhal2016) found that of the 22.7% leprosy-affected persons studied in Bareilly, 11.4% suffered from generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), 4.5% from panic disorder, 4.5% from mixed and other anxiety disorders and 2.3% from obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). In addition to GAD, OCD and panic disorder, Rocha-Leite et al. (Reference Rocha-Leite, Borges-Oliveira, Araújo-De-Freitas, Machado and Quarantini2014) also identified agoraphobia (11.7%) and social phobia (9.2%) among leprosy patients in Salvador, Brazil. In addition, a few studies identified mixed anxiety and depressive disorders among leprosy-affected persons (Bhatia et al., Reference Bhatia, Chandra, Bhattacharya and Imran2006; Jindal et al., Reference Jindal, Singh, Mohan and Mahajan2013; Bakare et al., Reference Bakare, Yusuf, Habib and Obembe2015). Erinfolami and Adeyemi (Reference Erinfolami and Adeyemi2009) found that Nigerian leprosy-affected persons studied had a significantly higher prevalence of anxiety than healthy persons, respectively 21.6 and 6.8%.

Suicide

Suicide, suicide attempts and suicidal thoughts are also common in leprosy-affected persons. Nine studies researched suicide (attempts and thoughts) among this group. According to Bharath et al. (Reference Bharath, Shamasundar, Raghuram and Subbakrishna1997), 33.3% of the investigated leprosy patients in Bangalore, India dealt with suicidal thoughts, and 20% had attempted suicide. Nishida et al. (Reference Nishida, Nakamura and Aosaki2006) investigated suicides among elderly leprosy-affected persons in a Japanese leprosarium over a period of almost 100 years and found that in that period, 41 suicides were reported. In a retrospective study by Shen et al. (Reference Shen, Liu, Zhou and Li2011), the deaths of 524 Chinese leprosy-affected persons were investigated. Sixteen percent of the cases committed suicide.

Schizophrenia

Another mental condition that was found among leprosy-affected persons is schizophrenia. This was found in five studies. However, the prevalence of schizophrenia was low: around 1%. Mahendra et al. (Reference Mahendra, Yaduvanshi, Sharma, Ali, Rathore and Kuchhal2016) found a prevalence of schizophrenia of 2%, but combined schizophrenia together with delusional disorder.

Mental distress

Three studies looked at mental distress among leprosy-affected persons (Leekassa et al., Reference Leekassa, Bizuneh and Alem2004; Damte et al., Reference Damte, Berihun, Berhe and G/Hiwor2011; Reis et al., Reference Reis, Lopes, Rodrigues, Gosling and Gomes2014). Two large studies among Ethiopian leprosy patients found a high prevalence of mental distress: 52.4 and 30.9% (Leekassa et al., Reference Leekassa, Bizuneh and Alem2004; Damte et al., Reference Damte, Berihun, Berhe and G/Hiwor2011). Another study among Brazilian leprosy-affected persons identified a prevalence of 48.5% (Reis et al., Reference Reis, Lopes, Rodrigues, Gosling and Gomes2014). In addition, Leekassa, Bizuneh and Alem (Reference Leekassa, Bizuneh and Alem2004) found that the prevalence of mental distress among Ethiopian people affected with leprosy is 12 times higher than in healthy people (Leekassa et al., Reference Leekassa, Bizuneh and Alem2004).

Other neuropsychiatric conditions

Investigators also described other conditions linked to leprosy including sleep disorder, dementia, hysteria, epilepsy, paranoid and psychotic state, senile degeneration, delusional disorder, hypochondriacal disorder, adjustment disorders, substance-related disorders, somatic symptom disorder, somatoform disorders, hyperactivity disorder and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. (Miyeko, Reference Kamiya1962; Kumar and Verghese, Reference Kumar and Verghese1980; Nishida et al., Reference Nishida, Nakamura and Aosaki2006; Su et al., Reference Su, Wu and Lin2012; Rocha-Leite et al., Reference Rocha-Leite, Borges-Oliveira, Araújo-De-Freitas, Machado and Quarantini2014; Nagargoje et al., Reference Nagargoje, Mundhada, Deshmukh and Saboo2015; Mahendra et al., Reference Mahendra, Yaduvanshi, Sharma, Ali, Rathore and Kuchhal2016). Hypochondriacal disorder and dementia were the only conditions that were mentioned in more than one study. However, the prevalence of hypochondriacal disorder was low in both studies (1%) (Rocha-Leite et al., Reference Rocha-Leite, Borges-Oliveira, Araújo-De-Freitas, Machado and Quarantini2014; Mahendra et al., Reference Mahendra, Yaduvanshi, Sharma, Ali, Rathore and Kuchhal2016). In addition, two Japanese studies and one Taiwanese study found dementia among the leprosy-affected persons studied (Miyeko, Reference Kamiya1962; Nishida et al., Reference Nishida, Nakamura and Aosaki2006; Su et al., Reference Su, Wu and Lin2012). The Taiwanese study found a high prevalence of dementia (45.7–50.4%) among leprosy patients (Su et al., Reference Su, Wu and Lin2012). However, it should be noted that all three studies were executed among elderly leprosy patients and no comparison was made with elderly people without leprosy.

Negative feelings and attitudes

In addition to mental health conditions that are diagnosable, other negative feelings and attitudes that can affect mental wellbeing were identified among leprosy patients in almost one-third of the articles.

Fear

One of the most frequent negative emotions leprosy-affected persons experienced was fear. A Brazilian study among 130 leprosy patients revealed that patients experience real fear (31.5%) and phantasmal fear (22.3%) (Cunha et al., Reference Cunha, Antunes, Da Silveira and Goulart2015). This fear can originate from different sources related to the disease or related to the person's environment. A study by Garbin et al. (Reference Garbin, Garbin, Carloni, Rovida and Martins2015) revealed that disease-related fear consisted of fear of disease sequelae (92.6%) and fear of dying (27.7%). In addition, Kaur and Ramesh (Reference Kaur and Ramesh1994), who studied female leprosy patients in Delhi, found that their patients were also afraid of receiving confronting questions about the disease (77.4%) and of infecting their family members (50%). Even when there was no judgement from family members, the fear of infecting or otherwise negatively affecting them remains among leprosy-affected persons (Anjum et al., Reference Anjum, Swarupa and Neeluri2017). Environment-related fear consists of fear of rejection, isolation, stigmatisation and prejudice (Kaur and Ramesh, Reference Kaur and Ramesh1994; Garbin et al., Reference Garbin, Garbin, Carloni, Rovida and Martins2015; Thilakavathi et al., Reference Thilakavathi, Manickam and Mehendale2015; Zambon Valério Pelizzari et al., Reference Zambon Valério Pelizzari, Oliveira De Arruda, Silva Marcon and Molena Fernandes2016).

Shame

Shame is also very common among leprosy-affected persons, mainly as leprosy causes physical disfigurements. Shame and embarrassment are related to the stigmatisation of leprosy (Van Brakel et al., Reference Van Brakel, Sihombing, Djarir, Beise, Kusumawardhani, Yulihane, Kurniasari, Kasim, Kesumaningsih and Wilder-Smith2012). To illustrate, it is often thought that leprosy is the result of wrong-doing or bad karma (Kaur and Ramesh, Reference Kaur and Ramesh1994; Zambon Valério Pelizzari et al., Reference Zambon Valério Pelizzari, Oliveira De Arruda, Silva Marcon and Molena Fernandes2016). In addition, leprosy-affected persons often perceive that others are afraid of contracting leprosy. As a result, they avoid talking about their disease or try to conceal it. One of the participants in the study of Zambon Valério Pelizzari et al. (Reference Zambon Valério Pelizzari, Oliveira De Arruda, Silva Marcon and Molena Fernandes2016) explained: ‘I am embarrassed, friends look and keep asking: What do you have? What did you do to your foot? I am ashamed to tell. I say it was an allergy.’ In addition, that same study revealed that even medical professionals advised leprosy patients to not discuss their disease with others (Zambon Valério Pelizzari et al., Reference Zambon Valério Pelizzari, Oliveira De Arruda, Silva Marcon and Molena Fernandes2016). Avoidance of social gatherings can be a result of shame leading to social isolation (Anjum et al., Reference Anjum, Swarupa and Neeluri2017).

Low self-esteem

As a result of the negative feelings and attitudes towards leprosy, leprosy-affected persons also experience low self-esteem. For instance, they believe that people may avoid people affected by leprosy, or that people may have less respect for them because of the disease, which results in insecurity (Hossain et al., Reference Hossain, Al Hadi, Boiragee and Parvin2016). Other researchers showed that discrimination and stigma are also related to low self-esteem (Beise et al., Reference Beise, Van Brakel, Kadri Sewa, Sumasto, Arief, Golo and Sheldon2012; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Hofker, Van Brakel, Marjolein, Seda, Irwanto and Bunders2014). Cunha et al. (Reference Cunha, Antunes, Da Silveira and Goulart2015) found that almost one-third of the participants from Minas Gerais, Brazil, experienced low self-esteem. In addition, Reis et al. (Reference Reis, Lopes, Rodrigues, Gosling and Gomes2014) found that over 60% of the leprosy-affected persons from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil studied lost confidence in themselves. The low self-esteem of patients manifests in, for example, not being willing to talk about the disease in public, isolation from family members and society, and self-stigma (Arole et al., Reference Arole, Premkumar, Arole, Maury and Saunderson2002; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Hofker, Van Brakel, Marjolein, Seda, Irwanto and Bunders2014; Anjum et al., Reference Anjum, Swarupa and Neeluri2017).

Loneliness, sadness and anger

A high intensity of emotions like loneliness, sadness and anger was also noticed in leprosy-affected persons. According to Kaur and Ramesh (Reference Kaur and Ramesh1994), 70% of the women with leprosy in their Delhi-based study experienced sadness after the diagnosis. Also, 62% revealed that they become angry over irrelevant matters (Kaur and Ramesh, Reference Kaur and Ramesh1994). Loneliness was also found to be present in leprosy-affected persons. A study of Nigerian leprosy-affected persons found that all research participants experienced loneliness (Enwereji, Reference Enwereji2015).

Low quality of life

Several studies reported a significantly lower quality of life (QoL) for persons affected by leprosy as compared with healthy controls. When leprosy patients from Mato Grosso, Brazil, were asked to rate their QoL in a study by Garbin et al. (Reference Garbin, Garbin, Carloni, Rovida and Martins2015), 37% scored it as ‘very bad.’ Joseph and Rao (Reference Joseph and Rao1999) found that South-Indian leprosy-affected persons scored significantly lower than healthy controls in the domains of physical and psychological QoL, level of independence, social relationships and environmental QoL. Low scores on the physical and psychological QoL domains were also found in a study in Bangladesh (Tsutsumi et al., Reference Tsutsumi, Izutsu, Islam, Maksuda, Kato and Wakai2007). Brouwers et al. (Reference Brouwers, Van Brakel and Cornielje2011) found that in Nepal, being affected by leprosy resulted in a decreased level of social participation and activity as compared to community controls, in addition to other negative impacts on QoL.

Mental health of family members

Three studies described the mental health impact of leprosy on family members of leprosy-affected persons. All three studied children and adolescents whose parents were coping with leprosy. In a study by Parashar and Kumar (Reference Parashar and Kumar2015), 100 Indian children of leprosy patients (mean age = 13.6) from Raipur were assessed regarding their physical and psychological health, social relationships and environment. Sixty percent of the children reported having low self-esteem, and none of them reported high self-esteem. In addition, this study found that the children often worried about contracting the disease (Parashar and Kumar, Reference Parashar and Kumar2015). Another study performed among 102 Nepali children of leprosy patients (mean age = 13.8) compared their health-related QoL, self-esteem and mental health with that of children of healthy controls (Yamaguchi et al., Reference Yamaguchi, Poudel and Jimba2013). They found that the former group scored higher on depressive symptoms, and lower on health-related QoL and self-esteem. The negative impact of having parents affected by leprosy was also visible in an Indian study by Antony and Broota (Reference Antony and Broota1991). They looked at the self-concept of children in Delhi, meaning the view of the child on his/her personality, ability and status in the world. They found that 76% of the children had a negative self-concept.

Determinants influencing mental health conditions

There were several determinants presented in the articles that can have an influence on mental wellbeing. In the following paragraphs these determinants will be discussed.

Stigma and discrimination

Stigma and discrimination were also frequently mentioned factors associated with psychiatric morbidity. Discrimination can result in unemployment, social and marital restrictions, low self-esteem, stress and self-stigmatisation (Beise et al., Reference Beise, Van Brakel, Kadri Sewa, Sumasto, Arief, Golo and Sheldon2012; Van Brakel et al., Reference Van Brakel, Sihombing, Djarir, Beise, Kusumawardhani, Yulihane, Kurniasari, Kasim, Kesumaningsih and Wilder-Smith2012). Stigma can harm the quality of life and social participation of persons affected, and increase mental distress, depression and fear (Bharath et al., Reference Bharath, Shamasundar, Raghuram and Subbakrishna1997; Brouwers et al., Reference Brouwers, Van Brakel and Cornielje2011; Damte et al., Reference Damte, Berihun, Berhe and G/Hiwor2011; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Anjum and Rao2014; Sillo et al., Reference Sillo, Lomax, De Wildt, Fonseca, Galan and Prado2016). According to a study among over thousand leprosy-affected persons in Indonesia, 36% experience anticipated stigma (Van Brakel et al., Reference Van Brakel, Sihombing, Djarir, Beise, Kusumawardhani, Yulihane, Kurniasari, Kasim, Kesumaningsih and Wilder-Smith2012). Sillo et al. (Reference Sillo, Lomax, De Wildt, Fonseca, Galan and Prado2016) described the influence of stigma on mental health in their study. They state that physical deformities are the main cause of stigma and disability. Because of the stigma attached to physical deformities, patients experience fear, avoidance, discrimination and prejudice. This can result in diminished mental health, for instance by causing depression and low self-esteem. On the other hand, when deformities cause functional impairments, leprosy-affected persons can become unemployed. Without employment, a decrease in social participation occurs, resulting again in diminished mental health (Sillo et al., Reference Sillo, Lomax, De Wildt, Fonseca, Galan and Prado2016).

In addition, several case studies revealed that stigma was often mentioned as a reason to attempt suicide (Chatterjee et al., Reference Chatterjee, Nandi, Banerjee, Sen, Mukherjee and Banerjee1989; Jopling, Reference Jopling1991). To illustrate this, in the study by Jopling (Reference Jopling1991), an Indian leprosy-affected person living in England stated that he would have committed suicide if he had been diagnosed in India, because of the stigmatisation of leprosy in his own country. In addition, 33% of the leprosy-affected persons in the study of Chatterjee et al. (Reference Chatterjee, Nandi, Banerjee, Sen, Mukherjee and Banerjee1989) admitted having suicidal thoughts because of social stigma.

Demographics

Several studies reported that they did not find a relation between mental wellbeing in people affected by leprosy and demographic factors, including age, gender, marital status, educational level, employment or housing (Bharath et al., Reference Bharath, Shamasundar, Raghuram and Subbakrishna2001; Erinfolami and Adeyemi, Reference Erinfolami and Adeyemi2009). However, multiple other studies did find an association between demographic factors and mental health, as delineated below.

Age. Bakare et al. (Reference Bakare, Yusuf, Habib and Obembe2015) and Chatterjee et al. (Reference Chatterjee, Nandi, Banerjee, Sen, Mukherjee and Banerjee1989) found that older age was related to mental wellbeing, specifically an older age at the onset of the disease. Damte et al. (Reference Damte, Berihun, Berhe and G/Hiwor2011) found similar results in a study regarding mental distress in Ethiopian persons affected by leprosy. Study results showed that patients in the age group of 48 to 57 had four times more mental distress than patients in a younger age group (18 to 27) (Damte et al., Reference Damte, Berihun, Berhe and G/Hiwor2011).

Gender. Two studies found that gender also influences mental wellbeing. According to Joseph and Rao (Reference Joseph and Rao1999) and Nagargoje et al. (Reference Nagargoje, Mundhada, Deshmukh and Saboo2015), female leprosy-affected persons in India had a significantly higher prevalence of psychiatric co-morbidity and a lower quality of life, in all domains, in comparison with male patients.

Marital status. Marital status of the leprosy patient can also have an influence on mental wellbeing. Separated or divorced leprosy-affected persons had a four times higher risk of mental distress than single persons, according to one study (Damte et al., Reference Damte, Berihun, Berhe and G/Hiwor2011). Similarly, another study argues that having no spouse can also negatively influence mental wellbeing (Bakare et al., Reference Bakare, Yusuf, Habib and Obembe2015).

Occupation, education and financial means. Occupation, education and financial means were also found to be associated with mental health status (Bharath et al., Reference Bharath, Shamasundar, Raghuram and Subbakrishna2001; Tsutsumi et al., Reference Tsutsumi, Izutsu, Islam, Maksuda, Kato and Wakai2007; Bakare et al., Reference Bakare, Yusuf, Habib and Obembe2015). A study by Nagargoje et al. (Reference Nagargoje, Mundhada, Deshmukh and Saboo2015) in Amravati, India, reported that leprosy-affected persons who were employed had a lower prevalence of psychiatric morbidity (71%) than those who were unemployed (90%). In addition, the same study found that illiterate leprosy patients (90%) experienced more psychiatric morbidity than literate patients (66.7%). Moreover, having a lower education level or lower income per year than other leprosy-affected persons was associated with a lower QoL (Tsutsumi et al., Reference Tsutsumi, Izutsu, Islam, Maksuda, Kato and Wakai2007). According to Thwaites et al. (Reference Thwaites, Anjum and Rao2014), unemployment was also a source of anxiety among leprosy-affected persons.

Environment. The environment was another demographic factor associated with mental health status. This was associated with QoL and social participation of leprosy-affected persons (Brouwers et al., Reference Brouwers, Van Brakel and Cornielje2011). Chatterjee et al. (Reference Chatterjee, Nandi, Banerjee, Sen, Mukherjee and Banerjee1989) studied hospitalised patients and outpatients in Kolkata and Purilia, India. They found that hospitalised patients had a significantly higher rate of mental illness (65%) than outpatients (25%). Enwereji (Reference Enwereji2015) found similar results, as that study found no depression among discharged leprosy patients. Additionally, Verma and Gautam (Reference Verma and Gautam1994b) compared leprosy-affected persons from Jaipur, India, living in an ashram with leprosy-affected persons living in a slum. They found that the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity was significantly higher among those living in the slums (Verma and Gautam, Reference Verma and Gautam1994b). However, a review found that people who are isolated from the community in ashrams and leprosy homes have a higher risk of developing mental illnesses (Singh, Reference Singh2012).

Antony and Broota (Reference Antony and Broota1991) also looked at the housing situation of the children of leprosy patients from Delhi. They found that 60% of the children living with their parents had a negative self-concept, in comparison with 85% of the children living in institutions for children of leprosy-affected parents.

Religion. No association was found between religion and mental health in the included studies.

Disease-related factors

Visible impairments. A significant link between disease-related factors and mental illness is visible impairments, and worries about developing them. Multiple studies have identified that having visible deformities increases the likelihood of mental illness and negative feelings among leprosy-affected persons (Kumar and Verghese, Reference Kumar and Verghese1980; Verma and Gautam, Reference Verma and Gautam1994a; Bharath et al., Reference Bharath, Shamasundar, Raghuram and Subbakrishna2001; Kisivuli et al., Reference Kisivuli, Othieno, Mburu, Kathuku, Obondo and Nasokho2005). For instance, according to a study by Thwaites et al. (Reference Thwaites, Anjum and Rao2014), the possibility of having complications such as blindness, ulcers and contractures was the predominant source of anxiety. Also, studies showed that persons with physical impairments have an increased risk of mental distress and low quality of life (Verghese et al., Reference Verghese, Mathew, Senseman and Karat1971; Leekassa et al., Reference Leekassa, Bizuneh and Alem2004; Tsutsumi et al., Reference Tsutsumi, Izutsu, Islam, Maksuda, Kato and Wakai2007; Damte et al., Reference Damte, Berihun, Berhe and G/Hiwor2011; Parashar and Kumar, Reference Parashar and Kumar2015). To illustrate this, Verma and Gautam (Reference Verma and Gautam1994a) found that the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among persons with visible impairments was 90%, while among those without deformities it was 47%. It is interesting that two studies found that impairments among males affected by leprosy are more frequently associated with mental illness than among females affected by leprosy (Joseph and Rao, Reference Joseph and Rao1999; Tsutsumi et al., Reference Tsutsumi, Izutsu, Islam, Maksuda, Kato and Wakai2007).

In addition, several studies found that patients with multibacillary leprosy experienced mental illnesses more often than patients with paucibacillary leprosy (Leekassa et al., Reference Leekassa, Bizuneh and Alem2004; Nagargoje et al., Reference Nagargoje, Mundhada, Deshmukh and Saboo2015).

Duration of disease. Another factor that might be associated with the risk of mental illness is the duration of the disease. Some studies argue that the duration of the illness does not affect the mental wellbeing of the person (Verghese et al., Reference Verghese, Mathew, Senseman and Karat1971; Verma and Gautam, Reference Verma and Gautam1994a; Bharath et al., Reference Bharath, Shamasundar, Raghuram and Subbakrishna2001; Kisivuli et al., Reference Kisivuli, Othieno, Mburu, Kathuku, Obondo and Nasokho2005). However, others did find evidence in their study for an association between the duration of the illness and poor mental health (Kumar and Verghese, Reference Kumar and Verghese1980; Bakare et al., Reference Bakare, Yusuf, Habib and Obembe2015; Nagargoje et al., Reference Nagargoje, Mundhada, Deshmukh and Saboo2015). For instance, Thwaites et al. (Reference Thwaites, Anjum and Rao2014) mentioned that the perception of incurability and re-occurrence of leprosy induces anxiety among people affected.

Treatment. The treatment of leprosy patients can also be a factor related to the development of mental illness. Nagargoje et al. (Reference Nagargoje, Mundhada, Deshmukh and Saboo2015) found that patients receiving treatment experience more psychiatric morbidity than patients who have completed treatment. The side effects of medications can cause anxiety among affected people (Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Anjum and Rao2014). The influence of treatment on mental wellbeing was also found in a retrospective study by Shen et al. (Reference Shen, Liu, Zhou and Li2011). They aimed to find out whether there was a relationship between the start of multi-drug-therapy (MDT) and suicide. By analysing the deaths of over 500 leprosy-affected persons from China, they found that shortly after the start of MDT, patients had an increased rate of suicide. In addition, the suicide rates also rose steeply after 6 months of using MDT (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Liu, Zhou and Li2011).

Moreover, drugs in the steroid class are also frequently used in the treatment of leprosy-affected persons (Lockwood, Reference Lockwood2000). The use of steroids is also related to psychiatric morbidity, for instance suicide and psychosis (Ross and Cetas, Reference Ross and Cetas2012).

Lifestyle and other factors

Kataoka and Nakamura (Reference Kataoka and Nakamura2005), who studied elderly persons affected by leprosy in Japan, concluded that higher GHQ scores were found among patients with no or a weak social network, and among patients with an inactive lifestyle. In addition, a study in Nepal found that participation limitations, along with inactivity, negatively influenced the quality of life (Brouwers et al., Reference Brouwers, Van Brakel and Cornielje2011). Social, emotional and health adjustment were also related to poor mental wellbeing in a study in India (Bharath et al., Reference Bharath, Shamasundar, Raghuram and Subbakrishna2001). In a study among children between 11 and 18 years old from Agra, India who suffered from leprosy, Chauhan and Dhar (Reference Chauhan and Dhar1981) found that anxiety was high among these children because of conflicts with family members, for instance thwarted attempts to gain affection from parents.

Interventions

In total, 11 interventions were described in the papers identified in the literature search (see Table 4). Interventions ranged from psychological counselling using techniques such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), to physical interventions, for instance surgical correction for the disfigured limbs of leprosy-affected persons. All interventions focused on improving self-esteem and self-worth and on motivating and enabling leprosy-affected persons to participate in society.

Psychological interventions

Studies showed that psychological interventions can improve the mental wellbeing of leprosy-affected persons. To illustrate this, the effect of therapeutic workshops to improve the rehabilitation of Brazilian leprosy-affected persons living in a leprosarium was studied by Leite and Caldeira (Reference Leite and Caldeira2015). The therapeutic workshops consisted of creating an environment where leprosy-affected persons could share experiences, socialise and collectively work on problems encountered. By analysing depression and QoL scores, they found that therapeutic workshops lowered the depression prevalence among Brazilians affected by leprosy from 79% to 46.8% and improved their quality of life significantly (Leite and Caldeira, Reference Leite and Caldeira2015).

Another form of psychological intervention that has been studied is CBT. Directed Imagination, a type of CBT in which desirable behaviour is promoted by training the imagination, was offered to 24 Mexican leprosy-affected persons [Pérez–Hernández et al. (Reference Hernández, Velasco-Rodríguez, Mora-Brambila, Vázquez-Espinoza, Maturano-Melgoza, Hilerio-López and Trujillo-Hernández2015)]. This therapy improved the adaptation level of the participants from 92% to 96%. In another study by Rahmawati and Yuniarti (Reference Rahmawati and Yuniarti2017) CBT was used with 25 leprosy-affected persons dealing with depression. Study results showed that after the intervention depression rates lowered with 12% (Rahmawati and Yuniarti, Reference Rahmawati and Yuniarti2017). Parashar et al. (2015) used a similar technique called Directed Imagination.

A study by Su et al. (Reference Su, Wu and Lin2012) investigated the effect of reminiscence group therapy (RGT) on depression rates among elderly leprosy-affected persons in Taiwan. They found that the RGT significantly lowered depression scores as measured with the Geriatric Depression Scale – Short Form (Su et al., 2011).

Physical interventions

Regarding physical interventions, Ramanathan et al. (Reference Ramanathan, Malaviya, Jain and Husain1991) studied the impact of surgical correction of 25 leprosy-affected persons with visible impairments, with the aim to improve their functional, occupational and economic status in society. According to this study, surgical correction diminishes anxiety levels by 24% and depression rates by 32% (Ramanathan et al., Reference Ramanathan, Malaviya, Jain and Husain1991). Another study combined physical with psychological interventions in institutionalised leprosy-affected persons. Mhasawade (Reference Mhasawade1983) investigated the effect of psychotherapy in combination with drug therapy on depression and anxiety rates among 120 Indian leprosy-affected persons. After psycho- and drug therapy, anxiety and depression rates were significantly lowered (Mhasawade, Reference Mhasawade1983).

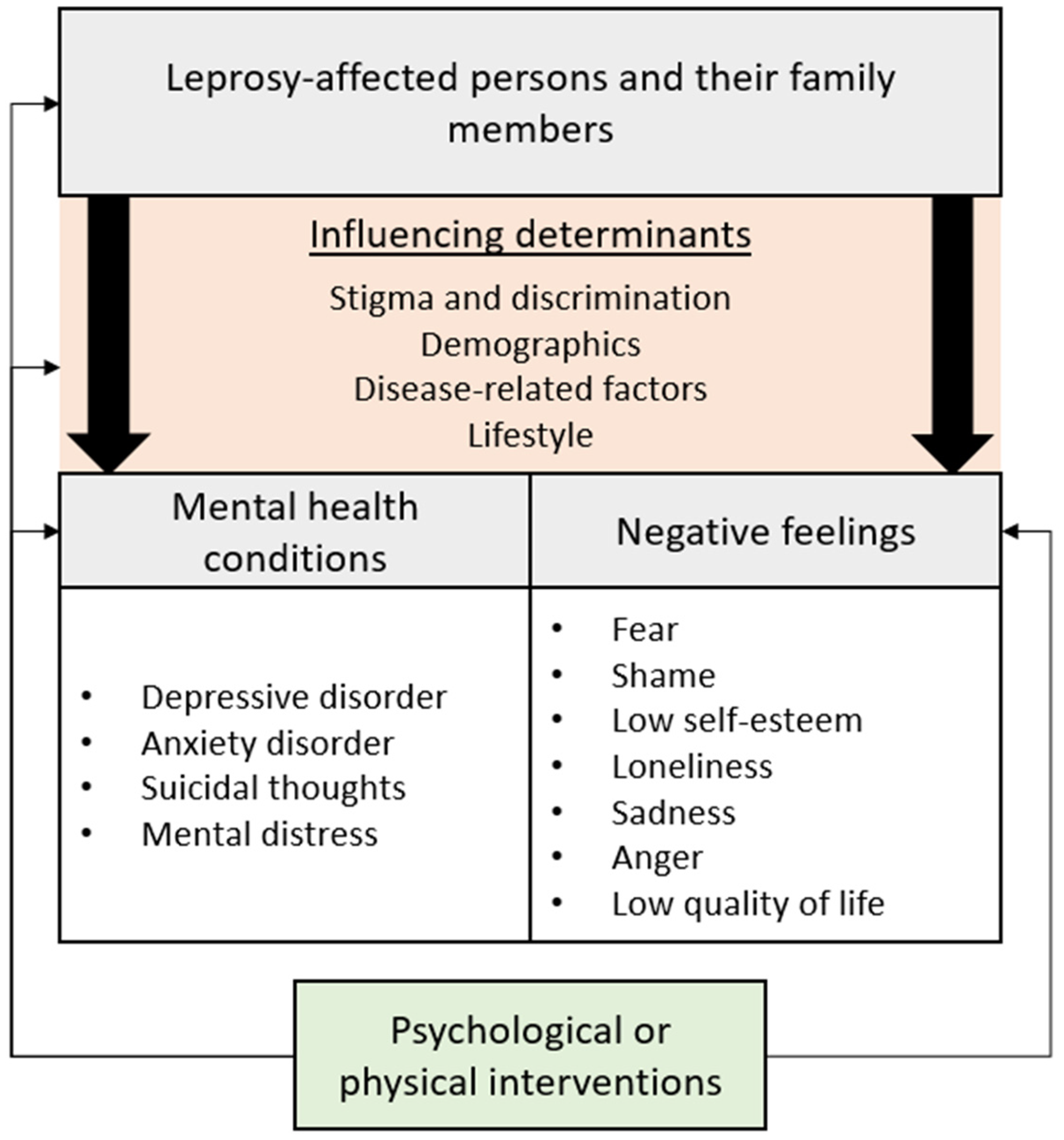

Model of the impact of leprosy on the mental health

The results of this study can be captured in a model (Fig. 2). This model shows the impact of leprosy on the mental health of those affected and their family members as found in literature. In addition, the influencing determinants are included. As stated in the previous section, there are promising psychological and physical interventions that target mental health conditions, negative feelings or the influencing determinants. These interventions can improve the lives of leprosy-affected persons and their family members.

Fig. 2. Model of the impact of leprosy on the mental health.

Discussion

This study investigated the impact of leprosy on the mental health of leprosy-affected persons and their family members by conducting a systematic literature review. Several psychiatric conditions were reported to occur frequently among leprosy-affected persons, specifically depression (up to 71%), suicide (attempts) (around 33%) and anxiety disorders (10 to 20%). In addition, this study found that children of leprosy-affected persons also experience poor mental health.

Leprosy has physical and psychological consequences that can lead to activity limitations, economic and physical dependence, social exclusion and stigma. All these factors are correlated and can worsen the mental wellbeing of the leprosy-affected persons (Bainson and Van den Borne, Reference Bainson and Van Den Borne1998; Van Brakel et al., Reference Van Brakel, Sihombing, Djarir, Beise, Kusumawardhani, Yulihane, Kurniasari, Kasim, Kesumaningsih and Wilder-Smith2012). Twelve out of 65 studies included in this systematic review compared the mental consequences of leprosy with either healthy controls or other patients with (chronic) diseases. Most of these studies showed that leprosy has a strong impact on mental health. For example, Bharath et al. (Reference Bharath, Shamasundar, Raghuram and Subbakrishna1997) compared psychiatric morbidity among patients with leprosy and patients with psoriasis in Bangalore, India. They found a significant difference between the two groups in the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity (12.2% for patients with psoriasis and 47.5% for patients with leprosy). However, more population-based studies are needed to draw conclusions regarding the mental impact of leprosy in comparison with other people, especially healthy populations. Additionally, poor mental health itself can have a negative impact on health outcomes, and may lead to low treatment seeking behaviour and treatment adherence, unemployment and work absence, social exclusion and stigma (Litt et al., Reference Litt, Baker and Molyneux2012; Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Druss and Perlick2014; Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Chatterji and Lahiri2017). Also, in children and adolescents the negative effects of poor mental health are visible. According to Fergusson and Woodward (Reference Fergusson and Woodward2002), adolescents coping with depression experience long-term complications regarding employment, education and health. Experiencing both leprosy and poor mental health is thus a heavy burden to carry for those affected and their family members.

Therefore, a proper evaluation of the burden of leprosy should take into account the psychological and social impact of the disease, as well as the chronic nature of many of its consequences. Incorporating the mental health burden of leprosy with the impact of physical impairments would give a different picture of the overall burden of the disease. Recent studies have attempted to do this for other NTDs with a long-term impact and an underestimation of the DALYs, for instance for leishmaniasis (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Mondragon-Shem, Hotez, Ruiz-Postigo, Al-Salem, Acosta-Serrano and Molyneux2017). Other measures to calculate the disability burden could also be considered, for instance, the SALSA Scale, a measure to estimate the level of activity and safety awareness, or the Participation Scale can be used to gain in-depth insights into the impact of leprosy (Van Brakel and Officer, Reference Van Brakel and Officer2008; Richardus, Reference Richardus2013). A study by van ‘t Noordende et al. (Reference Van ‘T Noordende, Kuiper, Ramos, Mieras, Barbosa, Pessoa, Souza, Fernandes, Hinders and Praciano2016) reviewed tools to assess and monitor NTDs including leprosy. They found that the Participation Scale was a suitable measure to assess the level of participation, as leprosy-affected persons often cope with participation restrictions. Another alternative measure that can be used to assess the burden of leprosy is the DAWLY. The DAWLY includes the number of productive years lost due to disability and takes the economic consequences of leprosy into account (Rao et al., Reference Rao, Darlong, Timothy, Kumar, Abraham and Kurian2013).

There are certain strengths and limitations to this study. First, this study provides a comprehensive overview of the mental burden of leprosy. In addition, other prominent negative feelings among leprosy-affected persons are presented, along with the mental burden on family members, determinants influencing the mental health burden and promising interventions to relieve the burden. A limitation is that, although multiple online databases have been searched, including databases specific for leprosy and NTDs, our search did not include databases specifically targeted at low and middle-income countries.

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the light of certain issues that may influence the occurrence and prevalence of mental health conditions among leprosy-affected persons. First, diagnosing a mental health condition is a complex process and is dependent on various factors. For instance, there is often a spectrum of illness that a person can fit into: depression can range from mild and transient episodes to severe depression with psychosis. In addition, there are many disorders that cannot be precisely diagnosed and that are categorised within ‘somatoform disorder’ (Mayou et al., Reference Mayou, Kirmayer, Simon, Kroenke and Sharpe2005). There are also cultural or language-related aspects of diagnosing mental conditions that relate to diagnostic tools, disease presentation and stigma. Diagnostic and screening tools are not always culturally or semantically appropriate. It is important that these tools are culturally validated before use in a new language or setting. Moreover, cultural factors may impact disease presentation. For example, in some cultures persons experiencing mental distress are more likely to present with physical complaints than to discuss emotions (Stevelink and van Brakel, Reference Stevelink and Van Brakel2013). In addition, the diagnostic classification of mental disorders can also provoke stigmatisation, as people having a mental illness are marked as different from others in society (Corrigan, Reference Corrigan2007). Second, it is possible that the mental disorders found among leprosy-affected persons are not manifesting because of leprosy, but because of other factors. The studies reviewed here often used univariate analysis and were thus not able to take confounding factors into account. For example, Verghese et al. (Reference Verghese, Mathew, Senseman and Karat1971) found an association between leprosy and neuroticism. According this study, leprosy patients share traits such as timidity, dependency and impulsivity with people who have confirmed neuroticism. However, these results can also be linked to living in a leprosarium. Another example is that leprosy is closely associated with extreme poverty, which is itself a risk factor for mental ill health (World Health Organisation, Reference World Health Organizationn.d.). In addition, study characteristics such as the setting, design or population size can also influence the occurrence and prevalence of mental conditions among leprosy-affected persons.

Also, the prevalence of certain disorders among leprosy-affected persons should be interpreted with caution in studies that did not include an adequate control group, as they could also be similar to the prevalence found in the general population, as is the case for schizophrenia (McGrath et al., Reference McGrath, Saha, Chant and Welham2008). Our review shows that leprosy is likely to have a substantial impact on mental wellbeing. Policy makers and healthcare providers should therefore give careful attention to measures to improve the mental wellbeing of those affected. If the mental health impact is taken into account when calculating the burden of disease associated with leprosy, a much more accurate picture can be communicated and the need for interventions to relieve the burden on leprosy-affected persons would be more evident. In addition, further population-based studies to document the prevalence of common mental health consequences such as depression and anxiety among persons affected by leprosy would help greatly to highlight the need for interventions. Several promising interventions to strengthen the mental wellbeing of those affected by leprosy, such as CBT were identified in this study. However, to assess the effectiveness of these interventions on a larger scale, more evidence is needed.

In addition, this study found that leprosy also has a great mental impact on the children of leprosy-affected persons. Further investigation is essential to explore the impact of leprosy on other family members, and to identify suitable interventions to mitigate any negative impact. Multivariate analysis is needed to determine the relation between other known determinants of mental wellbeing, leprosy and mental health. Identifying which determinants play a role in the mental wellbeing of leprosy-affected persons can help to establish suitable interventions. Further investigation of the burden of leprosy on mental wellbeing, should identify the determinants involved, based on which suitable interventions directed at strengthening the resilience and mental health of leprosy-affected persons can be formulated. Additionally, the quality of several studies was poor or could not be assessed due to the limited information provided. We recommend that large, well-designed studies be done to provide data on mental condition in persons affected by leprosy and on the effectiveness of various interventions. These should be reported according to state-of-the-art protocols.

Limitations

This systematic review focused on a selected number of electronic search engines. However, one of these, Infolep, contains almost all known publications on leprosy, including grey literature. We are therefore confident that no major studies were missed, except if they were published in a language not included in this review and did not contain at least an English abstract. The search strategy was not specifically designed to find intervention studies, but since the overall number of studies on this topic is very limited, we are confident that the studies included give a complete overview of the possibilities regarding interventions. The information contained in quite a few studies was insufficient to rate the quality of the studies objectively. However, given the limited number of studies available on this topic overall, we decided not to exclude these from the review.

Conclusion

This is the first study to consolidate the evidence of the mental health impact of leprosy on affected persons and their family members through a systematic literature review. A number of mental health disorders and negative emotional states were identified among leprosy patients and their family members. Depression and anxiety are particularly common, and a higher prevalence was found among leprosy-affected persons in comparison with healthy controls. Low self-esteem and low QoL were found among those affected by leprosy and the children of leprosy-affected persons. Additionally, determinants were identified that may influence mental wellbeing other than leprosy itself, especially stigma and discrimination and (visible) impairments, but also demographic factors and other disease-specific factors. Further research is necessary to identify the burden of disease of leprosy, taking the mental health consequences into account, and the impact of leprosy on the mental wellbeing of family members. In order to prevent and mitigate the mental health impact of leprosy, interventions are needed to strengthen coping mechanisms of those affected, to treat mental health conditions such as depression in this population, and to change negative community attitudes towards those affected by the disease, as stigma is a key contributor to mental ill health.

Acknowledgements

This research was facilitated by NLR and supported by VU University Amsterdam. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge the advice and support received from Prof David Molyneux and Dr Frederick Bailey from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

None.