What happens to autocratic elites after democratization? More specifically, which autocratic elites are more likely to return to cabinet positions under democracy? The comparative democratization literature has provided extensive explanations of why, when. and how democratization happens (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2014; Boix Reference Boix2003; Schmitter and O’Donnell Reference Schmitter and O’Donnell1986). Although the vast majority of these explanations put (autocratic) elites at their core (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2014, Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Collier Reference Collier1999; Diamond Reference Diamond1999; Schmitter and O’Donnell Reference Schmitter and O’Donnell1986), they mostly use slow-moving, structural variables (such as inequality, GDP/capita, political culture) or institutional variables (presidentialism/parliamentarism, inherited constitutions, and the like) to infer the incentives, roles, and consequences of political elites during and after democratization. This aggregated approach prevents us from examining which autocratic elites are replaced, whether and when they remain connected to political power, and how democratization shapes their political trajectory. Given that elites are the most immediate and significant explanatory variable in this literature (Diamond Reference Diamond1999; Huntington Reference Huntington1993), this is a major gap in our understanding of autocratic elites’ trajectory after transitions.

This puzzle is best illustrated by the trajectories of two former cabinet members, Jarbas Passarinho and Joao Paulo Velloso, during Brazil’s military dictatorship. They entered the cabinet of the military regime around the same time (Passarinho in 1967 and Velloso in 1970), held multiple cabinet portfolios and positions (three each), and spent a similar amount of time (eight years) in the cabinet during the military dictatorship.Footnote 1 However, only Passarinho was part of the core group of individuals who exerted power during Brazil’s military dictatorship. Despite having similar autocratic cabinet careers, Passarinho returned to cabinet under democracy as Minister of Justice (1990–92) under the Collor administration, whereas Velloso never made a return to democratic politics.Footnote 2 Passarinho’s return was driven by President Collor’s need to appease and build consensus with former autocratic elites in the Congress (Power Reference Power2010). I propose that Passarinho’s example is illustrative of the two mechanisms that explain which former autocratic elites are more likely to return to a democratic cabinet: credibility within former autocratic elites’ circles to represent their interests under democracy, and experience in running state institutions acquired as a senior member of the autocratic cabinet. More generally, understanding which autocratic elites are given a cabinet position in the subsequent democracy is important because their return is associated with increased inequality (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2014), lower democratic quality, institutional weakness (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2014; Power Reference Power2010), and antidemocratic practices (Albertus and Deming Reference Albertus and Deming2021; Power Reference Power2010). Against this background, I offer a novel theory of which former autocratic elites are more likely to return to cabinet positions under democracy.

Former autocratic elites are those individuals who occupied cabinet positions in an autocracy that gave them the power and organizational capacity to run the government and to have broad policy-making influence (Albertus Reference Albertus2015).Footnote 3 This includes all individuals who occupied leadership positions (president, prime minister, vice president, vice prime minister, etc.), cabinet-level positions, and appointed leadership of key institutions in a regime (such as junior ministers, attorneys general or chief justice, central bank governors, United Nations representatives, or ambassadors). Individuals in these positions generally wield power on behalf of the autocrat and are part of the inner circle of power in an autocracy (Albertus Reference Albertus2019; Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Nalepa Reference Nalepa2022; Svolik Reference Svolik2012).Footnote 4 The phenomenon of returning autocratic elites to a democratic cabinet is defined as autocratic revolving doors (ARD).Footnote 5 This paper seeks to explain which of these former autocratic elites are more likely to return to a democratic cabinet through a demand and supply logic.

Cabinet formation in democracies is a highly political process in which positions are assigned as a means to reinforce or secure the support of various constituents and societal groups and to transfer material and symbolic rents to political allies (Carboni Reference Carboni2023). On the demand side, leaders of cabinets in new democracies need to reward political allies, provide goods and services to their constituents, and appease surviving autocratic elites. To achieve these aims, they need cabinet members with political experience who can run institutions, as well as develop and implement policies. Moreover, in new democracies, appeasing (or not) old authoritarian elites is considered one of the key dilemmas of democratization (Ang and Nalepa Reference Ang and Nalepa2019; Huntington Reference Huntington1993) because they can derail the democratization process (Diamond Reference Diamond1999; Power Reference Power2010). Thus, leaders of democratic cabinets need to make a trade-off between these demands.

On the supply side, cabinet leaders need to select from a pool of former autocratic elites who can help them meet these demands. Former autocratic elites selected for democratic cabinet positions need to have both policy and political experience in running state institutions, as well as the capacity to signal former autocratic elites (and their networks) that their interests will be protected under democracy (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Karl Reference Karl1987). I theorize that the variation in political experience that elites gained under autocracy and the characteristics of the cabinet positions (i.e., being part of the core, time in office, and prestigiousness of the portfolio) they held under autocracy allows us to explain the demand and supply logic that drives autocratic revolving doors in new democracies.

I test the observable implications of the theory using a time-series cross-sectional, elite-level dataset of 12,949 former autocratic cabinet members using WhoGov data (Nyrup and Bramwell Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020) for 68 new democracies (that had been autocracies at any point between 1966 and 2020) across 91 different democratic spells (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014). The empirical analysis uses a novel measure of the autocratic revolving door at the elite-democratic spell level: It captures whether a former autocratic cabinet member returned as a senior cabinet member (i.e., minister, president, vice president, or prime minister) at any point after a transition to democracy (Olar Reference Olar2025b). The independent variables measure whether elites were part of the core group of cabinet members in an autocracy, the number of years they spent in an autocratic cabinet, and whether they held a prestigious portfolio (i.e., finance and budget, foreign affairs, internal affairs, defense, or national security). The results (estimated via logistic regression) offer strong support for the theory. More specifically, elites who were part of the core and held a prestigious portfolio in an autocratic cabinet are more likely to return to the cabinet under democracy, whereas those former autocratic leaders who spent more time in an autocratic cabinet are less likely to return to democratic cabinet positions. The results are robust to alternative model specifications, estimation strategies, and potential confounding factors due to observed or unobserved factors.

This article makes several contributions to the existing literature on democratization, authoritarian legacies, and revolving door politics. First, it offers a novel theory of autocratic revolving doors with testable observable implications at the elite level. This theory complements existing explanations of revolving door dynamics from advanced democracies (Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2016; Eggers and Hainmueller Reference Eggers and Hainmueller2009) and goes beyond existing explanations focusing on the trajectory of political leaders (Baturo Reference Baturo2016). Second, it provides systematic and generalizable empirical evidence of which autocratic elites are more likely to make a democratic comeback. It complements the evidence of elites’ trajectory from Latin America (Albertus Reference Albertus2019; Albertus and Deming Reference Albertus and Deming2021; Reference Albertus and Deming2022), which has had very distinct democratization dynamics (Hagopian and Mainwaring Reference Hagopian and Mainwaring2005) that do not fit existing theoretical accounts (Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013). Third, the article provides a novel measure of autocratic revolving doors that allows for systematic empirical tests of existing explanations about how and when autocratic elites survive democratization. This novel measure allows scholars of democratization to further unpack the conditions under which democratization can be considered a blank slate (Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020) and what the potential consequences are of autocratic elites’ comeback to democratic politics. Moreover, it opens up the possibility of more fine-grained testing of propositions from modernization theory that focus on elites’ incentives post-democratization (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2014; Boix Reference Boix2003; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2012).

Autocratic Revolving Doors in New Democracies

The autocratic revolving door is a phenomenon through which former autocratic elites return to cabinet positions after a democratic transition. It builds on the concept of revolving doors in advanced democracies in which cabinet members continue to play a prominent role in politics, business, or civil society after leaving office, very often by leveraging the connections and experience they gained while in office (Braun and Raddatz Reference Braun and Raddatz2010; Theakston and De Vries Reference Theakston and De Vries2012). In this article’s context, the concept of autocratic revolving doors captures the movement of political elites who occupied positions in an autocratic cabinet to democratic cabinet positions after the transition to democracy. Although being a cabinet member may be the “apex of a political career” (Blondel Reference Blondel1991, 153), the political careers of autocratic elites are not over after democratization or after they have left office (Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1966, 118). Paradoxically, democratization allows former autocratic elites to reach another apex of their political career because it opens the possibility for certain elites to return to a cabinet position in democracy. The theory developed in this article aims to explain this phenomenon.

The return of autocratic elites after democratization has been observed in contexts as diverse as Tunisia (Carboni Reference Carboni2023), Kenya (LeBas and Gray Reference LeBas and Gray2021), the Philippines and Indonesia (Buehler and Nataatmadja Reference Buehler and Nataatmadja2021), Brazil (Power Reference Power2010), and the former communist countries of Eastern Europe (Pakulski, Kullberg, and Higley Reference Pakulski, Kullberg and Higley1996). Data on the return of former autocratic elites to democratic cabinets show that autocratic revolving doors are the norm, rather than the exception. In 68 of 72 former autocracies, at least one former autocratic elite occupied a cabinet position in the new democracy between 1966 and 2020.Footnote 6 Although only 7.8% of all autocratic elites are able to return to a democratic cabinet, they occupied these positions for more than 55% of all new democratic country-years. As figure 1 shows, autocratic revolving doors seem to be a very sticky phenomenon: It can take as long as 37 years for new democracies to have a cabinet free of former autocratic elites.Footnote 7 On average, it takes about 10.5 years for a new democracy to have a cabinet free of former autocratic elites, and former autocratic elites spend about the same amount of time in office (approx. 3.3 years) as cabinet members of established democracies.Footnote 8 Given the scale and frequency of autocratic revolving doors, there are still several gaps in existing literature that prevent us from gaining a more nuanced understanding of what explains this phenomenon.

Figure 1 Proportion of Former Autocratic Elites in Democratic Cabinets since the Transition

Elites’ behavior and their incentives post-democratization have long been the focus of the vast literature on democratization and democratic consolidation (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Albertus Reference Albertus2019; Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2014, Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Ang and Nalepa Reference Ang and Nalepa2019; Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2014; Bermeo Reference Bermeo1992; Boix Reference Boix2003; Collier Reference Collier1999; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2012; Huntington Reference Huntington1993; Nalepa Reference Nalepa2022; Przeworski Reference Przeworski1991; Schmitter and O’Donnell Reference Schmitter and O’Donnell1986). Elites play a central explanatory role in existing research (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Collier Reference Collier1999; Diamond Reference Diamond1999; Huntington Reference Huntington1993); however, the literature uses mostly slow-moving, structural level indicators (such as inequality, GDP/capita, GDP growth or political culture) or institutional variables (presidentialism/parliamentarism, inherited constitutions, etc.) to infer the incentives, roles, and actions of political elites during and after democratization. Although these measures are useful in understanding the structural determinants of democratization and democratic consolidation, they limit our ability to understand which elites are more likely and better placed to survive democratization and continue their political career. Understanding which of these elites are more likely to return can be consequential for democracy because they bring with them institutional and political practices that may be undemocratic, and their return results in decreased political accountability and increased clientelism (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Power Reference Power2010). For example, in Brazil former autocratic elites have hindered transitional justice for human rights violations that took place during the military dictatorship (Pinheiro Reference Pinheiro1998). Similarly, Loxton (Reference Loxton, Loxton and Mainwaring2018) documents how the election of former dictators as presidents under democratic spells in the Dominican Republic, Madagascar, and Nicaragua were followed by democratic reversals as a direct result of their actions while in office.Footnote 9

Most explanations of autocratic actors’ adaptation to democratic politics focus on how political parties reinvent themselves as democratic competitors (Flores-Macías Reference Flores-Macías, Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2002, Reference Grzymala-Busse, Loxton and Mainwaring2018, Reference Grzymala-Busse2020; LeBas Reference LeBas, Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Loxton Reference Loxton, Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Loxton and Mainwaring Reference Loxton, Mainwaring, Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Loxton and Power Reference Loxton and Power2021; Riedl Reference Riedl, Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Slater and Wong Reference Slater, Wong, Loxton and Mainwaring2018, Reference Slater and Wong2013; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017) and the ways in which autocratic elites use constitutions to protect their interests (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Negretto Reference Negretto2006). The autocratic successor party literature highlights a puzzling tension between having an authoritarian inheritance (Loxton Reference Loxton, Loxton and Mainwaring2018) or an usable past (see Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2002, Reference Grzymala-Busse2020) and having authoritarian baggage (Loxton Reference Loxton, Loxton and Mainwaring2018) or a need to break with the past (see Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse, Loxton and Mainwaring2018). The former captures resources that can be used by autocratic actors to succeed and thrive under democracy, therefore making their return more likely. The latter captures liabilities in relation to voters and political opponents that stem from having supported an autocratic regime and its policies (Nalepa Reference Nalepa2010), therefore reducing the likelihood of return for autocratic actors. The findings of this literature highlight that, for autocratic successor parties, the benefits of the authoritarian inheritance trump the liabilities of authoritarian baggage (Loxton Reference Loxton, Loxton and Mainwaring2018). This article advances this debate on the trade-offs of an autocratic past by examining which characteristics of a former autocratic elite’s cabinet position allow them to navigate these trade-offs and become politically successful under democracy.

Most of the literature on the reappearance of parties or individuals as democratic players (Loxton and Mainwaring Reference Loxton, Mainwaring, Loxton and Mainwaring2018; Loxton and Power Reference Loxton and Power2021) relies on evidence aggregated at the country level (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2014, Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018), uses case studies and anecdotal evidence (Buehler and Nataatmadja Reference Buehler and Nataatmadja2021; LeBas and Gray Reference LeBas and Gray2021; Loxton and Power Reference Loxton and Power2021), and is concerned with explaining the trajectory of former dictators (Baturo Reference Baturo2016; Debs Reference Debs2016). One exception is the work of Albertus (Reference Albertus2019), who shows that inheriting an authoritarian constitution increases the likelihood of autocratic elites returning and reduces the likelihood of punishment in the context of Latin America. More recently, Albertus and Deming (Reference Albertus and Deming2022) show that autocratic elites’ preexisting networks before the installation of autocracy shape their ability to avoid punishment and return to positions of influence after democratization in Latin American democracies. Similarly, Nalepa (Reference Nalepa2022) examines how transitional justice initiatives shape political elites’ fates after democratization at the country level.

Although this literature is extremely compelling in its theoretical explanations and empirical evidence, it still has several gaps. First, we lack an understanding of what makes some former autocratic elites more likely to reappear at the forefront of democratic politics. Is their return solely driven by their ability to “game” democracy in their favor (i.e., designing a constitution before the transition; Albertus Reference Albertus2019)? Or do elites’ experience, networks, and skills allow them to leverage their autocratic past, even in the absence of a gamed democracy in their favor? Similarly, are all autocratic elites equally likely to return to cabinet under democracy, or are certain elites more likely (than their peers) to do so? Second, it is not clear how far the groundbreaking work of Albertus and Deming (Reference Albertus and Deming2021, Reference Albertus and Deming2022) can be generalized beyond the context of Latin America, given that the countries of this region share a common history of colonialism, militarism, and inequality in wealth and income that differs from other regions (McSherry Reference McSherry2012). Moreover, existing research (Hagopian and Mainwaring Reference Hagopian and Mainwaring2005; Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013) shows that standard theories of modernization do not hold in the case of Latin America because of its regional and temporal specificities. For example, the average rate of cabinet positions occupied by former autocratic elites (4.1%) in the new democracies of Latin America is less than half of the global average (10%) for the time period 1966–2020.Footnote 10 Thus, we need additional evidence that complements the findings from the Latin American context (Albertus and Deming Reference Albertus and Deming2021, Reference Albertus and Deming2022) to draw generalizable inferences on the phenomenon of autocratic revolving doors.

Finally, cross-national research on the fates of elites after democratization only considers those elites who were in office one year before the transition (Albertus Reference Albertus2019; Albertus and Deming Reference Albertus and Deming2021; Nalepa Reference Nalepa2022). Although this data may give us an insight into the determinants of returning autocratic elites, it may also suffer from selection bias. Elites who are in office prior to the transition may be sitting ducks who were selected to take the blame for the regime’s demise, while more influential elites choose to withdraw from power temporarily so that they can reinvent themselves after the transition. For example, Kamel Morjane was the minister of defense and of foreign affairs for almost six years under the former autocratic leader of Tunisia, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Once it became clear that Ben Ali was isolated and unable to hold power, Morjane asked publicly for Ben Ali’s ouster and then resigned, one day before the government fell (Wolf Reference Wolf2023). Through this move, he tried to create some distance between himself, the protests, and the regime in an “attempt at authoritarian regeneration” (Wolf Reference Wolf2023, 197). The following day, he was appointed minister of foreign affairs in the new caretaker government, which he had to leave two weeks later because of pressure from protesters (The Guardian 2011). Alternatively, elites who are in power prior to the transition may see the downfall coming and choose to stay in the cabinet to game democracy in their favor. Establishing the direction of the selection bias may be difficult without additional observational insights, but the data used here indicate that 463 of the 1,017 autocratic elites who returned to a democratic cabinet were not in office the year before the transition. Thus, by only considering elites who were in office the prior year, we risk underestimating how many autocratic elites make a comeback in new democracies.

A Theory of Autocratic Revolving Doors

Autocratic revolving doors are explained through a demand and supply logic that drives cabinet formation in new democracies. It is generally a highly political process in which cabinet positions are assigned to individuals based on the weight of the constituency they represent not only to secure and reinforce their support but also to offer rewards to political allies (Carboni Reference Carboni2023). Thus, individuals chosen for cabinet are representative of various constituencies and interest groups (Arriola Reference Arriola2009; Arriola, DeVaro, and Meng Reference Arriola, DeVaro and Meng2021).

On the demand side, constituencies and interest groups demand access to cabinet positions and their associated material and reputational benefits in exchange for their support of the leader. For example, in Brazil, party leaders use access to cabinet positions not only as a token of prestige in local constituencies (Power Reference Power2010) but also as a mean to obtain funds for their constituencies (Mauerberg, Oliveira, and Guerreiro Reference Mauerberg, de Oliveira and Guerreiro2023). To reward voters and their constituencies, cabinet leaders need cabinet members with expertise and capacity in policy making who can deliver public goods, services, and benefits (De Mesquita et al. Reference de Mesquita, Bruce, Siverson and Morrow2003). However, in new democracies, cabinet leaders also need to assuage the concerns of former autocratic elites who worry that democracy jeopardizes their interests (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2014, Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018). Because the process of democratization rarely dismantles the support and interest networks of autocratic elites (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Carboni Reference Carboni2023; Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020), the demands for access to political power and protection of the interests of former elites are quite strong, because elites still have enough influence and power to derail the democratization process (Diamond Reference Diamond1999; Power Reference Power2010).

On the supply side, various interest groups supply individuals from which leaders select individuals for cabinet positions. Cabinet leaders need to select competent ministers who can implement policies and deliver public goods to reward constituencies. At the same time, some ministers need to represent the interests of former autocratic elites to ensure their support and prevent them from derailing democracy (Diamond Reference Diamond1999; Power Reference Power2010). Appointing ministers without experience may hamper efforts to ensure bureaucratic efficiency (Weber Reference Weber2019) and lead to inadequate delivery of public goods (Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference de Mesquita, Bruce, Siverson and Morrow2003), and bringing former autocratic elites into the cabinet may lead to an uneven democratic playing field, in which policy making follows the interests of a minority (Nalepa Reference Nalepa2022).

The theory of autocratic revolving doors in this article aims to develop observable implications on how the demand side of cabinet formation—rewarding constituents and appeasing networks of autocratic elites—explains the supply side, or which former autocratic elites are more likely to be part of a democratic cabinet.Footnote 11 We can accomplish this by examining how the autocratic cabinet experience and the characteristics of the position that elites held under autocracy affect their likelihood to be part of a democratic cabinet. The main assumption underlying this theory is that the time spent as an autocratic cabinet member allows elites to develop or strengthen their negotiation and policy-making skills and build support networks and political capital that can be used under democracy (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2020). The ability of autocratic elites to navigate politics and complex situations in the absence of formal rules and in the presence of impending violence in autocracies (Svolik Reference Svolik2012) prepares them well for the more peaceful and predictable nature of democratic politics. Thus, former autocratic elites will have the policy-making and negotiation skills required to run state institutions and implement policies, while also having access and credibility within existing autocratic elites’ networks. This occurs because the individuals who occupied a cabinet position in an autocracy had the power and organizational capacity to run the government while exerting broad policy-making influence (Albertus Reference Albertus2015). They generally wielded power on behalf of the autocrat by making and implementing policies (Albertus Reference Albertus2015), were invested in the survival of the regime (Svolik Reference Svolik2012), and had access to the inner circle of power (Albertus Reference Albertus2019; Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Nalepa Reference Nalepa2022).

In the next three subsections I discuss the autocratic cabinet characteristics that systematically explain which former autocratic elites are more likely to return to democratic cabinet; this is followed by two descriptive examples (from Tunisia and Brazil) to illustrate the logic of the argument.

Autocratic Cabinet Positions and Revolving Doors

The first characteristic of an autocratic cabinet position that shapes autocratic revolving doors is whether an individual has been part of the core of government in an autocratic regime. The core group of elites are the ones with executive decision-making power who dictate the policies of an autocracy and use the country’s strategic resources to govern (Albertus Reference Albertus2015). In autocracies, individuals in these positions are the leaders of (and strongly embedded in) the regime’s support networks (Arriola Reference Arriola2009). A core position also allows them to develop contacts and relations with other elites at various levels and acquire the deal-making and negotiation skills necessary for wielding power in an autocracy. Under autocracy, these skills are developed in a fine balancing act of power sharing in which elites strive not to become too powerful and so threaten the dictator and risk getting removed (often violently) but are still influential enough to pursue their own interests and implement regime policies (Svolik Reference Svolik2012).

The core group includes the most senior positions of an autocratic cabinet such as cabinet ministers, prime ministers, presidents, vice presidents, vice prime ministers, members of the politburo, and members of a military juntaFootnote 12 (Nyrup and Bramwell Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020). It does not include junior cabinet autocratic positions such as secretaries of state, junior or deputy ministers, attorneys general or chief justices, central bank governors, UN representatives or US ambassadors. This more junior (i.e., non-core) group of individuals are still important in autocratic governance but are not essential for regime survival, and they can be replaced more easily by the dictator. In contrast, purges of the core group of elites may backfire and increase the likelihood of leader removal (Angiolillo and Matthews Reference Angiolillo and Matthews2024; Baturo and Olar Reference Baturo and Olar2024).

In comparison to their junior cabinet peers, core cabinet members have experience in running important state institutions and mobilizing support for their own interests and political agendas (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018), and they have private information about the state strategic resources and other actors in society (Nalepa Reference Nalepa2010, Reference Nalepa2022). These positions also give these elites more visibility within society, which makes it more difficult for them to obfuscate their autocratic past after a transition to democracy (Loxton Reference Loxton, Loxton and Mainwaring2018). Thus, core elites have more credibility within the autocratic interest groups that usually survive democratization. These autocratic interest groups prefer elites from the core group in democratic cabinets because they can trust that these individuals share the same material interests and that they have the skills and knowledge to defend these under democracy. Thus, selecting cabinet members who were part of the core autocratic ruling groups assuages fears of the redistributive potential of democracy held by former autocratic elites and their interest groups (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2014).

Put simply, their presence in cabinet positions both reassures and meets the demands of former autocratic elites that their interests will be protected under democracy and that the changes in governance rules will not jeopardize their access to state resources. Similarly, their experience in running important state institutions allows them to implement their own policy goals; that is, they have the skills needed to meet demands for the delivery of public goods to voters. For example, when Rached Ghannouchi formed the caretaker government in Tunisia, after the ouster of Ben Ali in January 2011, he nominated ministers who had been part of Ben Ali’s cabinet because their “great expertise was needed in this phase…so they can put in place this ambitious programme of reform” (Wolf Reference Wolf2023, 208). Conversely, elites who were not a part of the core group had lower levels of responsibility and might not be able to signal an equally strong commitment to defend autocratic elites’ interests under democracy. Moreover, their more junior positions might not give credibility to their abilities as policy makers. This leads us to the first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Autocratic elites who were part of the core cabinet in autocracies are more likely to return as cabinet members in democracies than autocratic elites who were never part of the core cabinet.

The second characteristic that shapes autocratic revolving doors is the number of years an individual has been a cabinet member in an autocracy. This serves as a proxy for elites’ ability to navigate politics and their embeddedness in autocratic elites’ networks. Autocratic politics can be a perilous line of work because political agreements are informal, there are no institutions to enforce power sharing, and violence is the ultimate arbiter of political conflicts (Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Very often, autocratic politics resembles a game of musical chairs in which the leader rotates the cabinet members to prevent them from developing strong bases and networks of support that could potentially threaten the leader’s power. For example, the former autocratic leader of Tunisia, Ben Ali, was so concerned with ministers conspiring against him that he tried to prevent having key ministers—of defense, the interior, and foreign affairs—meet without him (Wolf Reference Wolf2023). Being able to navigate and survive (politically) in such a perilous environment creates extremely robust individuals with usable political skills. Moreover, more time spent in an autocratic cabinet increases the amount of private information these individuals can leverage in democratic politics because they know “where the bodies are hidden” (Ang and Nalepa Reference Ang and Nalepa2019). A lengthier time in autocratic cabinets also increases elites’ credibility within elites’ circles: Former autocratic elites (outside the cabinet) are more likely to trust that these individuals will protect their interest when selected for a cabinet position. Similarly, a longer time in cabinet equates to a longer list of contacts that former autocratic elites can use to leverage favors and wield power. These attributes, acquired through a longer time in office, allow these elites to position themselves in a way that makes them valuable coalition members of governments in new democracies. Put simply, the number of years spent in an autocratic cabinet not only highlights a strong commitment to autocratic elites’ interests but also signals policy-making abilities that can be useful for leaders of democratic cabinets, therefore meeting the demands of cabinet formation in new democracies. This leads us to the second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: Autocratic elites with longer tenures in autocratic cabinets are more likely to make a return to cabinet in new democracies than those with shorter tenures.

Finally, the prestige of the portfolio an individual held under autocracy also affects their return to cabinet in new democracies. The prestigiousness of a cabinet portfolio is defined by control over policy, visibility of the position, and access to strategic resources (Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012). The most prestigious portfolios are the ones of finance, foreign affairs, home/internal affairs and defense. This conceptual category captures all individuals who had responsibilities in these policy areas in a cabinet, ranging from full ministers to deputy ministers or heads of governmental agencies (e.g., central bank, chief justices, head prosecutors, heads of army or intelligence, etc.). Dictators generally cannot rule alone, and they face a loyalty–competence trade-off when deciding who to co-opt as cabinet members (Gueorguiev and Schuler Reference Gueorguiev and Schuler2016; Zakharov Reference Zakharov2016) because they fear that elites may amass too much power at the expense of the leader (Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Individuals with more prestigious cabinet portfolios are more likely to be purged in the event of a failed coup because they have access to strategic resources through which they can attempt to remove the leader (Bokobza et al. Reference Bokobza2022). This indicates that cabinet positions in an autocracy are not merely window dressing in which individuals are used interchangeably (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008), and it is plausible that having access to a more prestigious portfolio might shape individuals’ networks of support, policy-making skills and access to strategic resources.

There are several ways in which cabinet portfolios’ prestige shapes elite cabinet members’ return in democracies. First, a more prestigious cabinet position requires individuals to develop a set of specialized skills that allows them to implement policies required to keep the government running. This experience provides individuals with the opportunity to position themselves as competent and experienced politicians who understand the inner workings of state bureaucracy and whose expertise is required to keep the institutions working after democratization. Moreover, given their expertise, leaders of a democratic cabinet know that these individuals have policy-making and implementation skills that can help leaders achieve their policy goals. Their appointment to a cabinet position reassures voters that the government can deal with political problems such as the state of the economy, public order, or social injustice. Second, the selection of these individuals in cabinet also signals to elite networks that their interests will be protected under democracy because the prestigious positions place them at the core of various interest networks under autocracy. This gives these elites private information about the strategic resources of the state and a list of contacts among elites interested in maintaining political influence and power under democracy.

Hypothesis 3: Autocratic elites who held more prestigious cabinet portfolios (i.e., budget/finance, foreign affairs, and internal/home affairs) are more likely to return as cabinet members in new democracies than autocratic elites who never held these portfolios.

However, we expect a different outcome for previous holders of the defense, military, and national security portfolios. These positions require individuals to use states’ resources to repress potential dissent and prevent citizens from organizing against the regime (Svolik Reference Svolik2012). How to deal with individuals responsible for human rights violations is a key question in the literature on transitional justice and democratization (Dancy and Thoms Reference Dancy and Thoms2021; Huntington Reference Huntington1993). More generally, individuals who used repression against potential or would-be opponents are more likely to be targeted by transitional justice measures (Dancy et al. Reference Dancy, Marchesi, Olsen, Payne, Reiter and Sikkink2019; Nalepa Reference Nalepa2022). If they avoid punishment, their past becomes a political deadweight that reduces their ability to leverage a return to a cabinet position in democracy. Moreover, individuals with training in the use of violence and background in the military always have the option to return to military life, rather than face the scrutiny of civilian political life (Debs Reference Debs2016; Geddes Reference Geddes1999). These arguments lead to the final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Autocratic elites who held a defense, military, and national security cabinet portfolio in an autocracy are less likely to return as cabinet members in new democracies compared to elites who held other types of portfolios.

A theoretical tension emerges because ministers with the defense, military and national security portfolios would also be considered part of the core group of governing elites. Therefore, for these individuals we have contradictory expectations (i.e., positive for the core position and negative for the defense portfolio) regarding their likelihood of being selected for cabinet under democracy.Footnote 13 The theory is agnostic whether one of these characteristics should trump the effects of the other, but this possibility is examined as an empirical extension in the analysis section.

Logic of the Theory

Examples of former autocratic elites from Tunisia and Brazil illustrate the logic of the theoretical argument. Kamel Morjane served as minister of defense (August 2005 to January 2010) and minister of foreign affairs (January 2010 to January 2011) in the autocratic cabinet of Tunisia’s Zine El Abidine Ben Ali who ruled between 1987 and 2011. During the protests that brought down Ben Ali in January 2011, Kamel Morjane strategically resigned his cabinet position, “hoping he would naturally emerge as one of the key leaders once the turmoil was under control” (Wolf Reference Wolf2023, 197). His appointment in the caretaker government the next day was presented as being based on his superior political experience and high profile. According to Morjane, Prime Minister Ghannouchi insisted that he “cannot have a minister who doesn’t know anybody and who isn’t known to anybody” (209). After a very short stint of only two weeks as foreign minister in the caretaker government and a failed presidential candidacy during the 2014 elections, Kamel Morjane returned as minister of public services, the country’s largest employer, in November 2018; this was part of a larger cabinet reshuffle in which Prime Minister Youssef Chahed looked to assert and consolidate his power vis-à-vis the incumbent president (Amara 2018). Moreover, Morjane’s appointment to the cabinet had the effect of luring back the nostalgic supporters of Ben Ali from the Sahel region (Ghanmi 2018) at a time when Prime Minister Chahed was looking to build support for the upcoming 2019 presidential elections. Morjane’s return was facilitated by the presence of the Nidaa Tounes Party in government; this party was bankrolled by former high-level authoritarian officials who had been part of Ben Ali’s government and were reinventing themselves as democratic actors. Morjane joined a cabinet filled with former elites from the Ben Ali era, the most prominent being Minister of Education Hatem Ben Salem and Minister of Finance Ridha Chalghoum (Bobin and Haddad Reference Bobin and Haddad2018), both propagandists for the former regime.Footnote 14 The return of Morjane and the broader reshuffle that included former elites of the Ben Ali era were defended on the grounds that social and economic stagnation and acute security challenges could only be solved by individuals with skills and solid experience in state institutions (Amara 2018; Bobin and Haddad Reference Bobin and Haddad2018).

The second example that illustrates the logic of the theory comes from Brazil, which was under military rule between 1964 and 1985. Jarbas Passarinho was appointed as minister of justice in 1990 by Fernando Collor de Melo, Brazil’s first democratically elected president after the 1985 democratic transition. Collor ran on an antiparty populist platform with the support of the ARENA/PDS coalition, comprising mostly former autocratic elites (i.e., ex-arenistas). He entered into an informal agreement with them in which they would support his candidacy—mostly because they feared the prospective redistribution of wealth under a Luis Inacio Lula da Silva presidency— and he would reward them with control of government ministries, access to state resources, and the prestige of having the support of the president (Power Reference Power2010). However, Collor reneged on this agreement after winning the election and aimed to maximize his autonomy by governing above the parties and the law (Power Reference Power2010; Weyland Reference Weyland1993). He appointed ministers from a variety of arenas to his cabinet: the private sector, universities, moderate labor unions, the centrist PMDB party, and even the opposition PSDB party (Weyland Reference Weyland1993); only a few positions went to members of the ARENA/PSD coalition.

Collor’s rapid decrease in popularity because of his failed economic policies and his party’s poor showing in the 1990 gubernatorial elections forced him to rethink the governing strategy that had alienated his allies in Congress. This is why Collor appointed Jarbas Passarinho as minister of justice in October 1990: His mission was to build a supraparty coalition in Congress drawing on his extensive contacts within the autocratic network (Power Reference Power2010). Passarinho was a widely respected veteran of the military who had held three cabinet portfolios—labor, education and social security—under the military dictatorship, was one of signatories of the notorious AI-5 decree that instituted military rule (Gaspari Reference Gaspari2016), and was the leader of the amnesty bill that President Figuereido passed for the members of military before the transition (Duffy 2007). The ex-arenistas agreed to participate in the supracoalition if they could “sit at the table where decisions are made” (Power Reference Power2010, 194).

The supracoalition was inaugurated in February 1991 along with the new legislature. The ex-arenistas took the first opportunity they could to impeach and remove Collor from office on the basis of corruption allegations made in 1992, despite his late attempts to obtain their support by bringing into cabinet former autocratic elites such as Pratini de Moraes and Angel Calmon de Sa. Reflecting on his reliance on ex-arenistas for support, Collor admitted that one cannot govern in Brazil without their support because they are professionals who know how to wield power (Power Reference Power2010, 195).

Research Design

To test these theoretical expectations, I built a dataset of 12,949 individual autocratic elites using data on cabinet members and ministers from the WhoGov dataset (Nyrup and Bramwell Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020) who occupied a cabinet position in an autocracy that democratized at some point between 1966 and 2020. The updated version of Geddes and colleagues’ (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014) data on political regimes from Chin and coauthors (Reference Chin, Carter and Wright2021) provided the regime data. The full dataset covers a total of 68 former autocracies with 91 different democratic spells and considers all individuals who occupied a cabinet position in a country that was an autocracy at some point during 1966 and 2020 and that democratized at least once in that period, allowing them the opportunity to return to a democratic cabinet.Footnote 15 The sample does not include countries that never democratized in this period (i.e., China and North Korea), nor countries that were continuously democratic over the same period (i.e. Japan, Italy, and the United Kingdom).

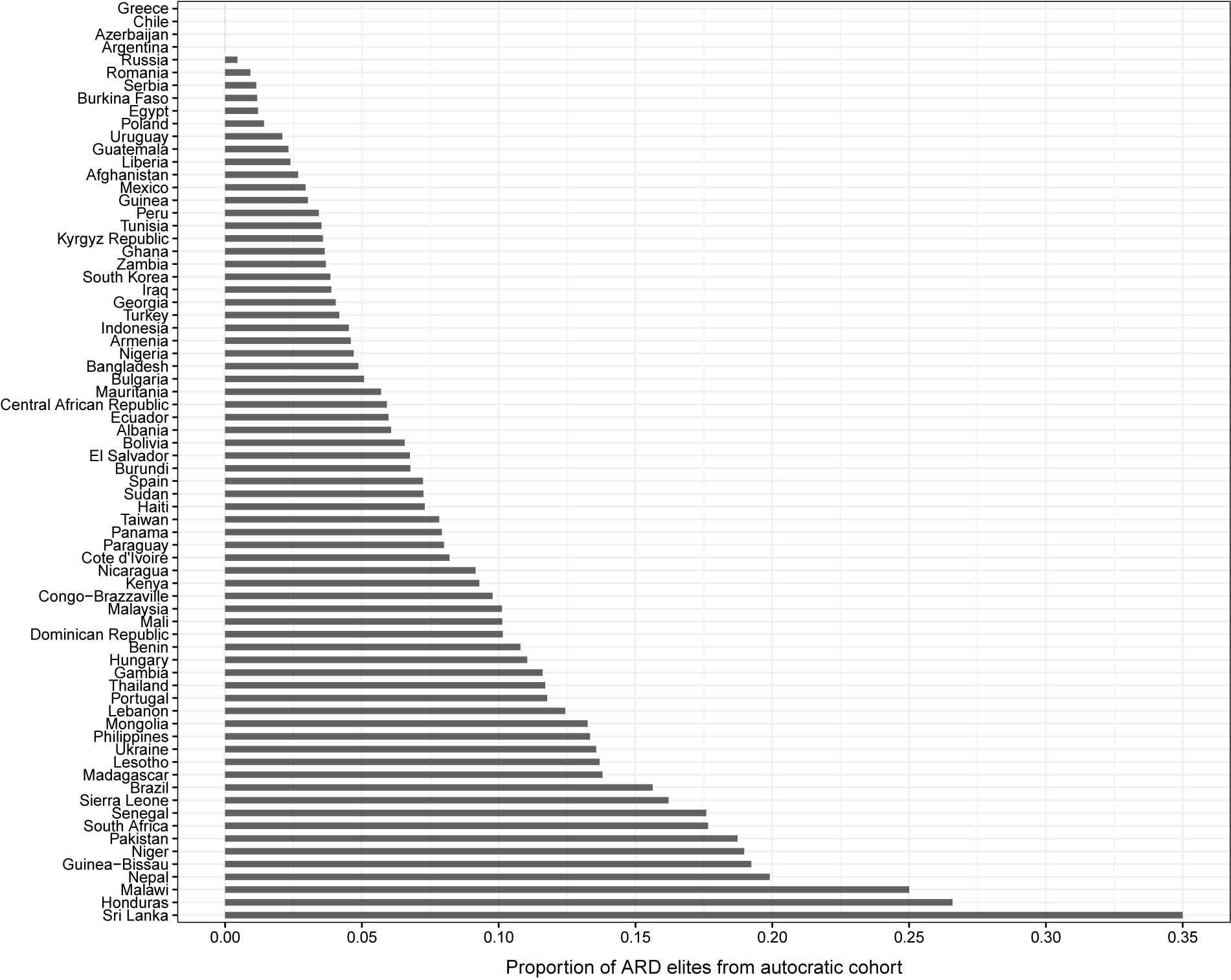

The analysis uses two different data structures of this dataset. The first version has a cross-sectional (CS) structure with the unit of analysis at the elite–democratic spell level. I chose this unit of analysis because I am interested in comparing which former autocratic elites are more likely to return to a democratic cabinet conditional on their role in an autocratic cabinet. The second version of the dataset has a time-series cross-section (TSCS) structure with the unit of analysis at the elite–democratic spell-year. The TSCS data structure allows me to account not only for potential aging effects at the elite level but also for how time dependency can act as an unobserved confounder for elites’ ability to leverage their past and return to democratic cabinet. Figure 2 shows the proportion of elites who occupied a cabinet position in a democracy who were also part of an autocratic cabinet between 1966 and 2020 from the total number of elites who were in office in democracies.Footnote 16

Figure 2 Proportion of Cabinet Elites in Democracies Who Also Had A Cabinet Position in Autocracies, 1966–2020

Dependent Variable

My research used data on cabinet members and ministers from WhoGov (Nyrup and Bramwell Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020) to generate a novel measure of autocratic revolving doors for the period 1966–2020. The WhoGov dataset contains information on cabinet members in 177 countries based on the chiefs of staff and cabinet members of foreign governments directory compiled by the CIA, which was originally compiled to be used by US government officials. The high degree of confidence in the data comes from it having been compiled by CIA-affiliated personnel with country insight. It contains a list of names and positions for each country-year, which allows us to see who and when an individual elite was part of the cabinet and what position they held.

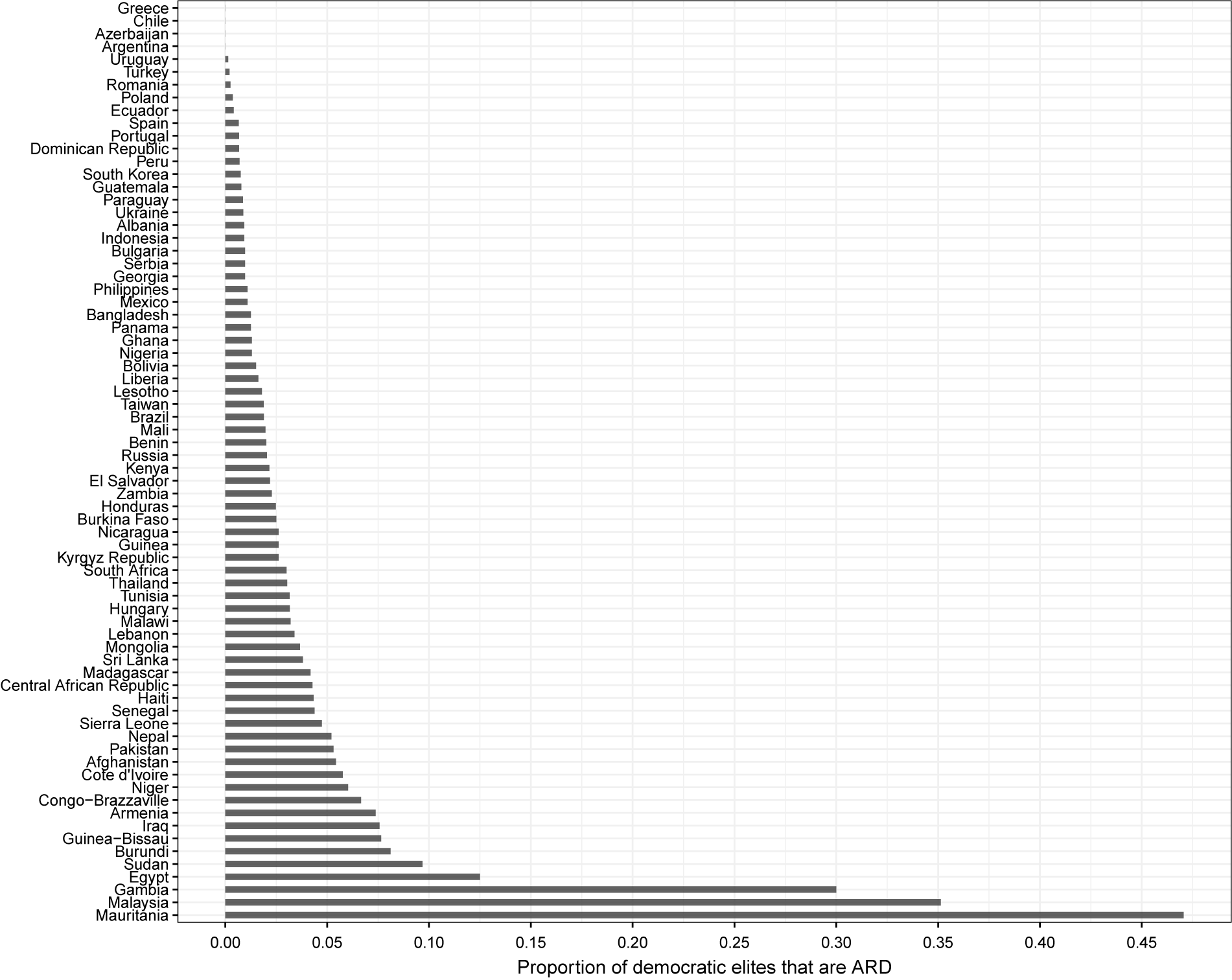

The dependent variable takes a value of 1 when an individual who was part of the cabinet in an autocracy reappears as a core cabinet member (such as a full minister, prime minister, president, or vice president) in a democracy, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 17 A total of 1,017 individual elites returned to democratic cabinet (7.8 %) from a total of 12,949 former autocratic elites. Figure 3 shows the proportion of each autocratic country cohort (i.e., the total number of individuals who were cabinet members in autocracies) who returned to a democratic cabinet in each country that democratized during the study period.

Figure 3 Autocratic Cohorts and Returning Elites in New Democracies, 1966–2020

Independent Variables

Hypothesis 1 is tested using a binary measure that captures whether an individual has been part of the core group of government in an autocracy, which includes senior positions such as cabinet ministers, prime ministers, presidents, vice presidents, vice prime ministers, members of the politburo, and members of a military junta (Nyrup and Bramwell Reference Nyrup and Bramwell2020). This variable allows us to compare autocratic elites who occupied these positions (i.e., equals 1) and those who occupied more junior positions (equals 0) such as secretaries of state, junior ministers, central bank governors, and so. Hypothesis 2 is tested using a variable measuring the number of years an individual has been part of the cabinet in an autocracy. Finally, hypotheses 3 and 4 are tested using binary variables capturing the type of portfolio an individual held while in an autocratic cabinet. Specifically, the variable testing hypothesis 3 captures whether an individual has held a foreign affairs, budget, or internal affairs portfolio, whereas the variable for hypothesis 4 captures whether an individual has held the portfolio for national defense, military affairs, or security. These variables capture all individuals who had responsibilities in these policy areas in an autocratic cabinet, regardless of their position’s seniority (i.e., core position or not). Individuals who were head prosecutors, members of the central bank, or head of the army or of the intelligence service are coded as holding these types of portfolios despite not occupying a minister position. An example of someone who held the national defense, military affairs, or security portfolio (Hypothesis 4) is Oleksandr Yakymenko, the head of Ukraine’s Security Service between 2013 and 2014 who was responsible for repressing the Maidan pro-democracy protests of 2014. Two binary variables code the portfolios held by cabinet members: One captures prestigious portfolios such as foreign affairs, budget or internal affairs, and the other captures only individuals who held the national defense, military affairs or security portfolios. These variables take a value of 1 if individuals held any of these portfolios, and 0 if they held any other portfolio or position within an autocratic cabinet. This coding allows us to compare which elites are more likely to return to cabinet conditional on the portfolio they had under autocracy (as a proxy for their policy-making abilities) and independent of whether they were part of the core of government.

Control Variables

Several control variables are included to account for alternative explanations of autocratic revolving doors. First, the model includes a variable measuring whether the country adopted a new constitution after democratization, because inherited autocratic constitutions have a positive effect on the ability of autocratic elites to avoid punishment and return to prominence in Latin American democracies (Albertus Reference Albertus2019; Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018). Second, the Cold War period may have offered more opportunities for elites to return in new democracies, while also reducing the propensity of new democracies to rely on human rights prosecutions or transitional justice measures to deal with the past (Albertus Reference Albertus2019; Ang and Nalepa Reference Ang and Nalepa2019). The analysis accounts for the potential differential effect of the Cold War and post–Cold War eras on elites’ ability to return to power during each democratic spell (Albertus Reference Albertus2019).

Third, the model accounts for the previous regime type based on the typologies proposed by Geddes and coauthors (Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014).Footnote 18 Inclusion of these regime type variables is important because regime type might affect the type of cabinet position certain individuals occupy, their ability to strategically select themselves into particular positions, or the extent to which the regime institutionalizes and creates networks of former regime insiders willing to support each other post-transition. For example, elites emerging from a personalistic dictatorship might have weaker political networks or not as much political capital because the previous leader has accumulated most of the power and the elites’ roles could have been mostly window dressing. In contrast, single-party regimes are characterized by high levels of co-optation, which in turn creates a larger network of individuals interested in protecting the autocratic status quo (Svolik Reference Svolik2012); individuals emerging from these regimes might have stronger networks on which they can rely to return to power. Further, elites from former military dictatorships might be more likely to be targeted by transitional justice mechanisms because there would be a collective responsibility for past human rights abuses, despite not holding the very portfolio responsible for these actions.

Fourth, the model also accounts for the gender of each elite because democratization increases the participation of female politicians in cabinet (Nyrup et al. Reference Nyrup, Yamagishi and Bramwell2023). The model also accounts for the level of economic development (GDP/capita and GDP growth) and population size (natural log) using World Bank data because structural conditions might affect the ability of elites to leverage their autocratic past.

Finally, the TSCS models account for time dependency by including measures of years since the transition and the amount of time since the individual has left office. This variable is included for two reasons: (1) Some individuals may already be old when they enter office in an autocracy, and they simply die before they can make a return; and (2) the private information individuals hold and their connection to networks may be diluted as more time passes since they left office.Footnote 19 The WhoGov data contain information on the birth year and death year for cabinet members, allowing us to account for the age of each elite, but only 49.3% of all individual elite observations have information on their birth year. One of the main purposes of this article is to produce generalizable findings about the determinants of autocratic revolving doors, and using a variable with so much missing data would induce potential selection bias. In the robustness test section, we use alternative measures to account for potential aging effects of elites (including this age variable), with the main results remaining substantively identical.Footnote 20

Data and Estimation Strategy

The return of autocratic elites is treated as an onset variable. In the CS models, the unit of analysis is at the elite–democratic level and the time-varying variables (i.e‥ GDP/capita, GDP growth and population size) are included as averages for the entire democratic spell. In the TSCS models, the unit of analysis is at the elite–democratic spell-year, and all variables are observed at this level, thereby varying from year to year. The time-varying variables are lagged one time period.Footnote 21 The hypotheses are tested using logistic regression models with democratic-spell fixed effects for two reasons. First, democratic spell unobserved heterogeneity (e.g., state capacity, culture, etc.) might affect elites’ ability to leverage their access to resources and networks and can also influence a society’s capacity to break away from its authoritarian past. Second, the inclusion of democratic-spell fixed effects allows us to explain within-elite variation, given the article’s focus on which elites are more likely to come back to democratic politics.

Empirical Results

Table 1 summarizesFootnote 22 the results of the regression analysis,Footnote 23 and figures 4 and 5 present the substantive effects of each variable. Models 1 and 2 estimate the effect of autocratic cabinet position characteristics on autocratic revolving doors in the cross-sectional (CS) data format, whereas models 3–5 estimate the same effects using the time-series cross-section (TSCS) data format that allows us to model the potential confounding effect of time since transition and exit from office. Because the results in the models are substantively identical, the interpretation and presentation of the substantive effects use the fully specified model 2, which shows within-elite variation.

Table 1 Autocratic Revolving Doors and Return to Office in New Democracies, 1966–2020

Standard errors in parentheses: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1

Figure 4 Average Marginal Effects of Autocratic Cabinet Position on Autocratic Revolving Doors in New Democracies, 1966–2020

Figure 5 Predicted Probabilities of Autocratic Revolving Doors Conditional on Time in Autocratic Cabinet, 1966–2020

Note: The dashed line and the scale on the left show the kernel density of the variable measuring the number of years that elites have been in autocratic cabinet.

First, the results indicate that elites who occupied a core cabinet position in an autocracy are more likely to return as cabinet members in democracy. The average marginal effect of this first variable is 7.5 percentage points, and it is by far the largest of all the variables explaining autocratic revolving doors. This result offers support to the first proposition of the theory (hypothesis 1) that being part of the inner core of elites who govern in an autocratic cabinet allows them to develop political skills, become embedded in interest group networks, and gain access to private information that they can leverage under democracy to continue their political careers.

Second, the results in figures 4 and 5 show that an increased tenure in autocratic cabinet reduces the likelihood that elites return to a democratic cabinet. The average marginal effect for this variable is substantively small, about 0.003 percentage points (figure 4). However, the predicted probabilities plot shows that the probability of returning to democratic cabinet is highest for individuals who spent less time in an autocratic cabinet and decreases with more time spent in an autocratic cabinet. This finding contrasts with the propositions behind hypothesis 2. One possible explanation for this finding is that there might be a trade-off between the ability to leverage the skills and resources to return to democratic cabinet versus the potential public outcry of such a move. In other words, individuals with more time spent as cabinet members in autocracies may be in a better position to leverage information and skills to return to office, but such a move may be politically costly for democratic actors because the public might recognize and punish them more easily (see figure 5).

To investigate the potential for this effect of time spent in a government position, figure 6 estimates the average marginal effects of being part of the autocratic core cabinet and the number of years one has spent in an autocratic cabinet.Footnote 24 The average marginal effect is highest when individual elites spent less time in core cabinet positions, and their probability of return decreases with each extra year spent in an autocratic cabinet.

Figure 6 Average Marginal Effect of Core Autocratic Cabinet Position Conditional on Time in Autocratic Cabinet, 1966–2020

Third, former autocratic elites who held a prestigious portfolio in an autocracy (i.e., foreign affairs, budget, or internal affairs) are about one percentage point more likely to return to office in democracies (figure 4). These results lend support to hypothesis 3 and to the more general argument that these specialized positions allow elites to market themselves as experienced politicians who can run state institutions. Fourth, hypothesis 4 does not receive support, because holding a national security portfolio in an autocratic cabinet does not seem to affect the probability of returning to a senior cabinet position in a democracy. Although these elites might still have a higher probability of being punished for overseeing efforts to repress dissidents and for violation human rights (Huntington Reference Huntington1993; Nalepa Reference Nalepa2022), this data do not allow us to investigate this pathway of return.Footnote 25 Finally, figure 7 examines the theoretical tension in which there are opposite expectations for individuals who occupied core positions (i.e., positive) and those who were also in charge of the national security portfolio (i.e., negative). The results from figure 7 indicate that holding the national security portfolio seems to trump the benefits of being part of the core of government, because core cabinet members have a higher likelihood of return compared to noncore cabinet members when they did not hold the national security portfolio. However, this difference disappears if they held the national security portfolio, providing some support for the political deadweight this portfolio brings to former autocratic elites.

Figure 7 Average Marginal Effect of Core Autocratic Cabinet Position Conditional on Holding the National Security Portfolio in an Autocracy, 1966–2020

The results reported here are robust to potential selection effects, unobserved heterogeneity, reserve causality, and alternative explanations. The Online Appendix provides a lengthy discussion and reports the results of a battery of robustness tests that support these findings.

Conclusion and discussion

This article presents novel theoretical propositions and empirical evidence on the phenomenon of autocratic revolving doors. The main argument proposes that cabinet formation in new democracies follows a demand and supply logic. On the demand side, cabinet leaders need to reward political allies, provide goods and services to their constituents, and appease surviving authoritarian elites. On the supply side, they need to choose from elites with experience in running state institutions and implementing policy. Thus, appointing to the cabinet former autocratic elites allows them to meet these goals. Doing so signals to autocratic elites that their interests will be protected under democracy, while also populating the cabinet with individuals with policy-making experience. Based on this logic, I developed observable theoretical expectations on how the characteristics of the autocratic cabinet experience affects elites’ return to a democratic cabinet. These expectations were tested using an original measure of autocratic revolving doors, showing that elites who were part of the core cabinet of government in autocracies are more likely to return to important executive positions in democracies. Moreover, a longer tenure in an autocratic cabinet seems to reduce the ability of elites to return to a democratic cabinet, whereas the effect of having held a prestigious portfolio seems to be more context dependent.

These findings have important normative implications for democratic consolidation. Existing research seems to converge on the idea that the return of the old guard is bad for democracy because it is associated with increased inequality (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2014), lower democratic quality, institutional weakness (Power Reference Power2010; Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018), antidemocratic practices (Power Reference Power2010; Albertus and Deming Reference Albertus and Deming2021), and a weaker commitment to human rights (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2000; Pinheiro Reference Pinheiro1998; Olar Reference Olar2025a). However, there is only scant empirical evidence on the consequences of returning autocratic elites because most evidence comes from the Latin American context (Albertus and Demming Reference Albertus and Deming2022) or case study research (Power Reference Power2010). Anecdotally, there are also examples when former autocratic elites have been at the forefront of prodemocratic decisions. For example, Poland’s rapid economic growth (GDP doubled), new constitution (1997), and accession to NATO and the European Union happened during tenure of Aleksander Kwaśniewski, who was the product of the Polish communist nomenclature and a former minister of youth and sport between 1987 and 1989. Similarly, Romania’s “Snagov Declaration” of 1995, which charted its path toward EU and NATO membership (Radwan 2016), was signed during the presidency of Ion Iliescu, once seen as Ceaușescu’s heir, who used to be a member of the Communist Politburo and cabinet, and whose legacy is mostly associated with the repression of protests during the 1989 revolution and the 1990 prodemocracy movements (Luft Reference Luft2009). Although these may be exceptions to the ways in which former autocratic elites can undermine democracy, we still have a limited understanding of the social, political, and economic consequences of autocratic revolving doors.

This article’s findings have additional implications for future research on democratization processes and authoritarian legacies. First, the natural extension of the theoretical framework on autocratic revolving doors should be the incorporation of structural-level (e.g., inequality, electoral rules, conflict, etc.) and international-level explanations (e.g., diffusion, international authoritarian actors, international alliances, etc.) alongside individual-level explanations. For example, individual characteristics may matter greatly for outcomes when elites have a high degree of autonomy (i.e., no appointed leader successor) but may matter little when constraints are severe (i.e., leadership rotation rules or an institutionalized party in power; Krcmaric, Nelson, and Roberts Reference Krcmaric, Nelson and Roberts2020). Second, the rules of cabinet formation may matter when former autocrats need to get elected into cabinet. One such avenue would be to examine whether certain types of democracies (i.e. presidential, semi-presidential, parliamentary) have different rates of autocratic revolving doors. In the presidential system the leader may have more unilateral power to bring in these elites into cabinet (following the logic of this article), whereas under parliamentary democracies, bringing these elites back might require more complicated bargaining between various political groups.Footnote 26 Finally, the literature on newly democratic citizens’ preferences for democratization shows that not all of them value democracy equally (Dinas and Northmore-Ball Reference Dinas and Northmore-Ball2020; Neundorf, Gerschewski, and Olar Reference Neundorf, Gerschewski and Olar2020), thereby creating conditions under which elites with an autocratic past would be preferred by voters. However, we still lack an understanding of how voters evaluate candidates with an autocratic past because most evidence on voters’ preferences comes from established democracies (Kirkland and Coppock Reference Kirkland and Coppock2018). Future research should supplement existing explanations of autocratic revolving doors with observational and experimental evidence of the conditions under which voters may select candidates with an autocratic past.

This article made several theoretical and empirical contributions to the literature on democratization, authoritarian legacies, and revolving doors politics. First, it provided a novel theory of autocratic revolving doors that explains how the characteristics of autocratic cabinet positions matter and determine autocratic elites’ ability to make a return to political office in democracies. This theory complements existing theories on revolving doors in democracies (Alexiadou Reference Alexiadou2016; Eggers and Hainmueller Reference Eggers and Hainmueller2009). Second, it provides novel empirical evidence of autocratic elites’ political trajectories post-democratization, evidence that goes beyond the case of Latin America (Albertus and Deming Reference Albertus and Deming2021) and beyond the focus on the trajectory of political leaders (Baturo Reference Baturo2016; Escribà-Folch and Krcmaric Reference Escribà-Folch and Krcmaric2017). Finally, the article offers a novel measure of autocratic revolving doors that allows us to disaggregate the pathways through which autocratic elites make a return to democratic politics. Moreover, this novel measure opens up the possibility of evaluating claims on elites’ incentives post-democratization (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2014; Boix Reference Boix2003; Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2012) and their consequences for democratic consolidation (Albertus and Deming Reference Albertus and Deming2021; Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020).

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592724002883.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Enrique Hernández, Jacob Nyrup, Carl-Henrik Knutsen, Austin Matthews, Monika Nalepa, Michael Albertus, the participants at the 2024 WhoGov workshop at the University of Oslo, and the journal editors and the four reviewers for very useful comments in revising this article. I also want to thank DCU’s Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences for providing funding to present this paper at the 2022 annual conference of the European Political Science Association. I am also acknowledging the financial support provided by the Royal Irish Academy through the Charlemont Grant to present this paper at the University of Chicago. Finally, I thank Rayssa Pinheiro for her help in editing and proofreading. All errors and omissions are my own.

Data Availability Statement

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/31MOAJ.