When on June 30, 1989, a group of middle-ranking army officers led by Brigadier Omer Hassan al-Bashir overthrew the civilian government of Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi in a coup d’etat, it was clear to most Sudanese that the coup leaders were ardent members of the Muslim Brotherhood. The new military regime was organized under the umbrella of the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) but the planning and decision-making were spearheaded by what was then a clandestine organization that was known as the Council of Defenders of the Revolution, known at time among many Sudanese as the Council of Forty (al-majlis al-arbeen). What was most noteworthy about the council was that it was headed by the influential Ali Osman Taha, the then president of the National Islamic Front (NIF) and well known to be the disciple of Hassan Turabi.

There is little question that in its first decade in power the Bashir regime pursued radical measures in domestic politics as well as foreign affairs. The regime’s Islamist-radical credentials became evident as early as December 1990 when the RCC formally announced a more comprehensive array of shari’a laws and promised to implement them by force. The expansion of Islamic penal codes included more stringent laws against apostasy, the enforcement of Islamic dress for women, and the exclusion of non-Muslims from holding high positions in the state bureaucracy. Moreover, with more stringent Islamicization policies came greater militarization. Under pressure from the leadership of the NIF, the RCC almost immediately created a paramilitary force, the Popular Defense Forces (PDF), to secure the Islamic revolution, “expand the faith,” and combat the non-Muslim rebellion in the south.1

In some respects the officers who made up the RCC followed in the pattern of the many other coups d’etats that have occurred throughout the African continent.2 However, it quickly became clear that the coup in the summer of 1989 in Sudan was different from the pattern of the two previous coups that the country witnessed in 1958 and 1969. Indeed, while Francois Bayart has observed that in many weak African states the construction of a hegemonic (authoritarian) ruling elite is often forged out of a tacit agreement between a diverse group of power brokers, intermediaries, and local authorities, the Islamist-backed coup in Sudan represented (at least in its first decade in power) the first time in the country’s history where an ideological party bureaucracy has sought total dominance over both state institutions and the entire population. Indeed, following the coup of 1989, the Bashir regime quickly outlawed all political parties, professional organizations, trade unions, and civil society organizations. Furthermore, backed by the NIF, the Bashir regime expanded its dominance over the banking system, monopolized the transport and building industries, and took control of the national media. In addition, for the first time, a ruling regime in Khartoum waged a concerted campaign to destroy the economic base and religious popularity of the two most powerful religious sects: the Ansar but particularly the Khatmiyya and its supporters.3

In the 1990s radical politics at home was matched with a new form of Islamist radicalism in foreign affairs under the leadership of the leaders of the NIF. In 1991, less than two years after coming to power and under the leadership of the late Hassan Turabi, Khartoum established the Popular Arab and Islamic Congress (PAIC), al-mutamar al-arabi al-shabi al-islami with the ambitious goal of coordinating Islamic anti-imperialist movements in fifty Muslim states. It was at this juncture that the Khartoum regime welcomed Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden not only opened accounts in al-Shamal, Tadamun, and Faisal Islamic Banks as a way to assist the regime financially, he also provided funds for al-Qa’ida camps on the outskirts of Khartoum.

But if the 1990s witnessed a strident form of Islamist radical politics, by the end of the decade Khartoum turned to more pragmatic policies withdrawing its support for Islamist radical organizations beyond its national borders. The turning point in Sudan’s support for international terrorism came in June 1995, when the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, assisted by the Sudanese intelligence service, carried out an assassination attempt against the Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak in Addis Adaba. In September, the African Union condemned Sudan for supporting terrorism, and by April 1996 the United Nations voted to impose diplomatic sanctions. Shortly after the sanctions were introduced, Sudan offered to turn Osama bin Laden over to the Saudi and US governments. Al-Qa‘ida’s ouster from Sudan represented a strategic break. The Islamist regime recognized that it was a losing proposition to support terrorists without considering their targets. Three years later, Sudan made peace with most of its neighbors and initiated regular counterterrorism talks with the United States. Following the September 11 attacks, the regime made a tactical choice to cooperate aggressively with US counterterrorism efforts as a way to reduce its international isolation.4

To be sure the increasing cost of sanctions did compel the Bashir regime to withdraw support for radical Islam. But the ideological evolution and the shift from radicalism to pragmatism on the part of Khartoum is better explained by domestic factors and, specifically, in the Bashir regime’s attempt to consolidate political power in the context of dramatic external and internal economic pressures. Indeed, in the first instance, the rise to power of Islamist politics in the 1990s represented a victory in the long-standing rivalry between Islamist radicalism, traditional Sufism, and ethnicity. Indeed, Sufism and ethnic loyalties have long provided a bulwark against the ideological appeal of Islamist radicalism of the type pursued by the Bashir regime. Nevertheless, under the leadership of the NIF, the Islamists (until recently) were able to prevail primarily because they were able to capitalize on a series of economic changes in the 1970s and 1980s. The NIF in particular developed a great deal of clout through its monopolization of informal financial markets as well as control of much of Sudan’s Islamic banking system.

The Islamists in Power and the Conflict over the “Black Market”

The recession of the mid-1980s triggered the turbulent politics that saw the passing of two regimes in less than a decade and the capture of the state by an Islamist military junta in the summer of 1989. As formal financing from the Gulf (as well as Western bilateral and multilateral assistance) dried up, giving way to the dominance of the parallel market, President Ja‘far al-Nimairi was forced to implement an IMF austerity program, removing price controls on basic consumer items. These measures sparked the popular uprising (intifada) that resulted in his ouster in 1985 and the election of a democratic government a year later. The civilian government, once again dominated by the old sectarian elites and characterized by interparty squabbling between the Umma Party and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), proved ineffectual in the face of Sudan’s severe economic crisis. Blocked from formal assistance due to a dispute with the IMF, the civilian government attempted to capture the all-important remittance flows from Sudanese nationals abroad by instituting a two-tier foreign exchange system in the latter part of 1988, but this attempt met with little success.5

Not surprisingly the very weakness of the civilian government led to significant progress in peace negotiations with the south based on a potential agreement that called for the repeal of the shari’a-based laws implemented in 1983. These efforts were forestalled, however, by the 1989 military coup, which was backed by the newly ascendant Islamist commercial class. Al-Bashir and the other members of the coup’s military cadre had been recruited by the Muslim Brotherhood, who during the 1980s made use of their newfound wealth and access to petrodollar funding to establish a host of tax-exempted Islamic welfare and propagation organizations offering generous stipends and scholarships to a select group of mid-ranking officers.6

As discussed in Chapter 2, in the 1970s and 1980s the role of Islamic banks and the monopolization of informal financial transactions played a key role in the rise of the Islamists, organized under the umbrella of the NIF as an instrument of political authority. Nevertheless, the military coup of 1989 radicalized the Islamicization process in Sudan, and the new government gave immediate attention to the financial sector. Throughout the 1990s, the NIF consolidated their power through coercive extractive regulatory mechanisms, most notably the formation of a tax police to intimidate tax evaders, and the execution of black marketers belonging to politically marginal groups. The state’s weakening resulted in more predatory and rent-seeking interventions. In addition to extracting revenue from local taxes, licensing fees, and bank loans, the state tried to capture a share of the informal urban market, exacting taxes on a percentage of the rental value on all shops, sheds, specialized markets, special services, and local development schemes.7

Whereas the parallel economy had been a source of strength for the Islamists in their rise to power, once they captured the state, and property rights were thus reassigned to their benefit, the parallel economy became a threat. One of the first measures of the Islamist state was to “declare war on black marketers, hoarders, smugglers, and traders who ‘overcharge,’ threatening them with execution.”8 Sudanese expatriates working in Arab states were ordered to declare their money at the Khartoum airport; traders were directed to post official price lists in their shops; and many street vendors were imprisoned. Most significantly, the al-Bashir regime ordered the issuing of a new Sudanese currency and gave Sudanese only two weeks to exchange the hard currency in their possession at the free-market rate. Although this ruling initially enabled Islamic banks to garner a significant amount of hard currency in the short term, government policy did not address the underlying production problem that made black marketeering and hoarding an endemic part of Sudan’s economy. Moreover, most merchants simply closed their shops or completely withdrew certain goods from the market. The general result was the exacerbation of the scarcity problem and hyperinflation averaging more than 2,000 percent per annum.9

The NIF’s Islamist regime’s preoccupation with, and even fear of, the parallel market was warranted, given its potential in terms of capital accumulation – a potential that members of the Islamist commercial class utilized to great effect during the boom. In an interesting historical twist of fate, just as al-Nimairi was beholden to a private sector dominated by the Islamists in the 1970s and early 1980s, the latter found themselves with the unenviable position of fighting over rents in the parallel market while promoting liberal macro-economic policies designed to lure external assistance to replenish the depleted coffers of the state and revitalize the commercial sector of the economy. These polices included the transfer of assets to Islamist clients as opposed to privatization in a competitive sense.

Meanwhile, most earnings of Sudanese living in the Gulf continued to be remitted home via the parallel channels. Although the recession reduced the total volume of remittance flows (Figure 5.1), the bankrupt Sudanese economy meant that a broad spectrum of Sudan’s middle class relied more and more on informal finances from the Gulf. The parallel market in foreign exchange circumvented both the national banks and the Islamic financial institutions, thereby contributing to the virtual merger of these former rivals attempting to reverse their losses in the “battle for hard currency.” In essence then, the crackdown on the black market in the 1990s represented an alliance between the faction of the Islamist commercial class (organized under the banner of the NIF) dominating the commercial banks and their supporters in the state bureaucracy to try to capture a significant portion of the earnings of Sudanese working in the Arab countries of the Gulf.

Figure 5.1 Trends in remittances as proportion of GDP, exports, and imports in Sudan.

Interestingly, conventional understandings of informal institutions commonly restrict informal markets to those not “officially” sanctioned by the state and assume, erroneously, that informal economic activities are generated exclusively as a direct result of excessive state intervention.10 In reality, and particularly in weak states, the expansion and operation of informal economic institutions are often produced by the actions and policies of the state elites themselves. In the case of Sudan after 1989, Islamist elites simultaneously countered and cultivated the expansion of black-market currency trade once they took over state institutions. Indeed, as in previous decades, the links between the formal institutions of the state and informal financial markets (i.e., black market) remained interdependent. But what changed after 1989 was that a shift occurred in the social and economic relations of power between a newly ensconced NIF-dominated state and rival sectarian and ethnic groups in civil society.

The crackdown against black-market dealers, for example, targeted only those black-market dealers who did not have links with the now Islamist-dominated state. Indeed, revenue generated from the black market continued to benefit key Islamist state officeholders. So despite the takeover of the state by the Muslim Brotherhood this did not curtail black-market transactions. Nor did it end the pattern of state collusion in parallel markets. Many of the black marketers before and after the coup of 1989 were Brotherhood supporters. Important NIF bankers, such as Shaykh ‘Abd al-Basri and Tayyib al-Nus, and the well-known currency dealer Salah Karrar, having become members of the Revolutionary Command Council’s Economic Commission, continued to speculate in grain deals, monopolize export licenses, and hoarded commodities in an effort to capture as much foreign exchange as possible. Moreover, while the Bashir regime implemented a “privatization” program this policy amounted to no more than the large-scale transfer of government-run public property into the “private” hands of Islamists. What is most notable is that Islamist financiers bought these assets with money made from currency speculation associated with remittance deposits.11

Having managed to gain control of the state, the Islamist-backed Bashir regime went about the task of consolidating power as quickly as possible. But while the NIF had built a strong middle class of Islamist-minded supporters they hardly had a hegemonic control of civil society. This was clear as early as the general elections of 1986 wherein the NIF managed to win approximately 20 percent of the vote but fell behind the two more popular Sufi-based parties: the UMMA and Democratic Unionist Party. Indeed, financial clout did not immediately translate into hegemonic control in civil society for the Islamists. As a result, following the coup of 1989, the Bashir regime considered it vital to marginalize rival factions of the middle class, while continuing to expand their urban base, built in the 1970s and 1980s, among a new commercial Islamist class. Since the informal economy represented an important source of revenue generation for a wide range of social groups the NIF-backed regime immediately targeted this important avenue of revenue generation. It is in this context, and in order to intimidate the big business families, which did not have any links with the Islamist movement or the NIF party in particular, that the junta accused several members of these rival business families with “illegal” black-market currency dealing and summarily executed them.

If the Islamist regime sought to take complete control of informal finance, they simultaneously went about consolidating their hold on the formal financial institutions of the state. The appointment of ‘Abd al-Rahim Hamdi and Sabri Muhammad Hassan, two of the most renowned individuals among Sudan’s Islamist financiers, as minister of finance and governor of the Central Bank, respectively, left little doubt as to the Muslim Brotherhood’s overwhelming dominance of the state’s financial institutions. This monopoly did not go unnoticed. In protests coordinated primarily by students, workers, and professional associations belonging to the Modern Forces (al-Quwwat al-Haditha) in 1993 and 1994, it was Islamic Banks, rather than public offices, that were stoned, ransacked, and burned.

The regime’s relationship with the IMF was particularly contentious. In 1986 the IMF declared Sudan ineligible for fresh credits because of its failure to enforce economic reforms. In 1990, the IMF went further, declaring Sudan “non-cooperative” due to the fact that it owed more than USD 2 billion in arrears and, in an unprecedented move, it threatened Sudan with expulsion. The government openly sought to improve its relations with the IMF, and under the guidance of Hamdi, floated the Sudanese pound (resulting in a six-fold rise in the value of the US dollar in relation to local currency), liberalized prices of key commodities, and reduced subsidies on a number of consumer commodities. But as the IMF continued to withhold assistance – as did most of the Gulf countries in reprisal for Khartoum’s support of Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War and its support of Islamist movements in the region – the al-Bashir regime was forced to reinstate subsidies in order to avert unrest in the urban areas.12

As the cost of living soared with the implementation of a wide-scale liberalization program, fears of potential social unrest prompted al-Bashir to dismiss Hamdi, a prominent advocate of the neoliberal economic policies. Hamdi’s removal was a sign of the state elites’ disenchantment with an economic liberalization program that was designed, but ultimately failed, to lure foreign assistance. But it was a cosmetic change: Hamdi’s successor as finance minister, ‘Abd Allah Hassan Ahmad, a former manager of Faisal Islamic Bank with strong ties to Europe- and Southeast Asia-based Islamist financiers, continued the neoliberal reforms. With the appointment of Sabir Muhammad al-Hassan, a high-ranking member of the Muslim Brotherhood, and former head of the Bank of Khartoum, as director of the Central Bank of Sudan, the Muslim Brotherhood continued to dominate fiscal and monetary policy. And members of the Muslim Brotherhood’s supporters continued to benefit from preferential allocations of bank loans, customs exemptions, and foreign currency for imports. The most important Islamist businessmen enjoyed lucrative asset transfers from the privatization of textiles, agribusiness, telecommunications, and mineral rights. Meanwhile, economic austerity measures, compounded by massive inflation, impoverished the majority of the Sudanese population, including civil servants and those engaged in the private sector but not affiliated with the Brotherhood. Only two sectors of society could meet the prohibitive cost of living: families receiving expatriate remittances and NIF members and their supporters.

While the Islamists demonstrated great willingness to liberalize practically every sector of the economy, they singled out the financial sector – the basis of their support – for regulation. In December 1994, the Transitional National Assembly (TNA) amended the Foreign Currency Dealing Act. The new amendment to the law closely regulated foreign exchange transactions, prohibiting the acquisition of foreign currency without official documents, and recommended that foreign exchange payable to the government be exempt from customs. This was designed to provide a strong incentive for expatriate Sudanese to deposit their remittances in state banks – a clear indication of the state’s foreign exchange shortage.13 The amended law also reduced the penalty for currency violations and called for the confiscation of currency instead of previous punishments, which ranged from twenty years’ imprisonment to hanging, and also recommended that a distinction be made between legitimate “possession of” and illicit “dealing in” foreign currency.14 The changes demonstrated the extent to which the state was willing to specify property rights in ways that would maximize revenue accruing to a small elite rather than to rival constituents in civil society. But these changes were too little and came too late to capture the gains from remittances. The regime’s brutal crackdown of black marketeering, as well as the onset of the Iraq war, saw a steep decline in expatriate remittances from the Gulf that fed the parallel market sent to the formal banks of the state. Moreover, Sudan’s deep economic crisis in the 1990s led to increasing migrations abroad with the result that remittances continued to fuel the parallel (informal) market and, from the perspective of the regime, took away a significant amount of the hard currency earnings that could have, otherwise, been deposited in the coffers of the state. Interestingly, state institutions became so starved for remittance-based financing that the regime often solicited the support from some of the wealthiest black-market traders in the country in return for allowing the latter to continue operations in contravention of the state’s own laws against black-market currency dealings. When the country’s most powerful currency trader, Waled al-Jabel, was incarcerated for black marketeering, the National Bank of Sudan (then headed by a prominent Islamist technocrat) intervened on his behalf because he agreed to provide this primary formal financial institution with much-needed capital from his own coffers.15

In lieu of a solid fiscal base and a productive formal economy, Khartoum resorted to extreme ideological posturing as its primary mode of legitimation. Specifically, the government formed a tactical alliance with the Islamic regime in Iran in hopes of attaining political support and economic assistance. Iran’s chief contribution was to provide arms (worth an estimated USD 300 million) that the regime then utilized to escalate the military campaigns against the southern insurgency, ongoing since 1983, and to establish a repressive security apparatus, parallel to the national army, in northern urban areas. Not only were millions of southerners killed or displaced as a result of an escalation in the civil war, but religious and ethnic cleavages deepened.

The regime further consolidated its rule through a systematic penetration of the civil service, including the monopolization of the important Ministry of Oil and Energy, thereby creating a powerful network throughout the bureaucracy. Immediately following their assumption to power in 1989, the NIF-backed regime pursued a program of dismissals based on ideological and security considerations, targeting supporters of other political parties, secularists, non-Muslims, and members of sectarian organizations, trade and labor unions, and professional associations. The same policy was applied to the armed forces, and officers of anti-Islamist sentiment were dismissed en masse. The Popular Defense Forces (PDF) was established, and its members given extensive ideological and military training befitting the political objectives of the Islamist authoritarian regime. These measures culminated in the formal declaration of an Islamic state in 1991 and in the introduction of a “new” Islamic penal code.

By the mid-1990s the Bashir regime pursued policies abroad as well as at home that reflected a decidedly Islamist radical agenda. In 1991, under the leadership of Hassan Turabi, Khartoum organized the Popular Arab and Islamic Congress (PAIC) hosted gatherings of known militant and terrorist organizations, and Khartoum gave moral, financial, and material support to mujahideen fighting in Bosnia, Albania, Somalia, and Chechnya. Thus, Sudan – one of the Muslim world’s most heterogeneous countries – became a center of international jihadism.

The Demise of “Islamic” Banking and the Struggle for Political Legitimacy

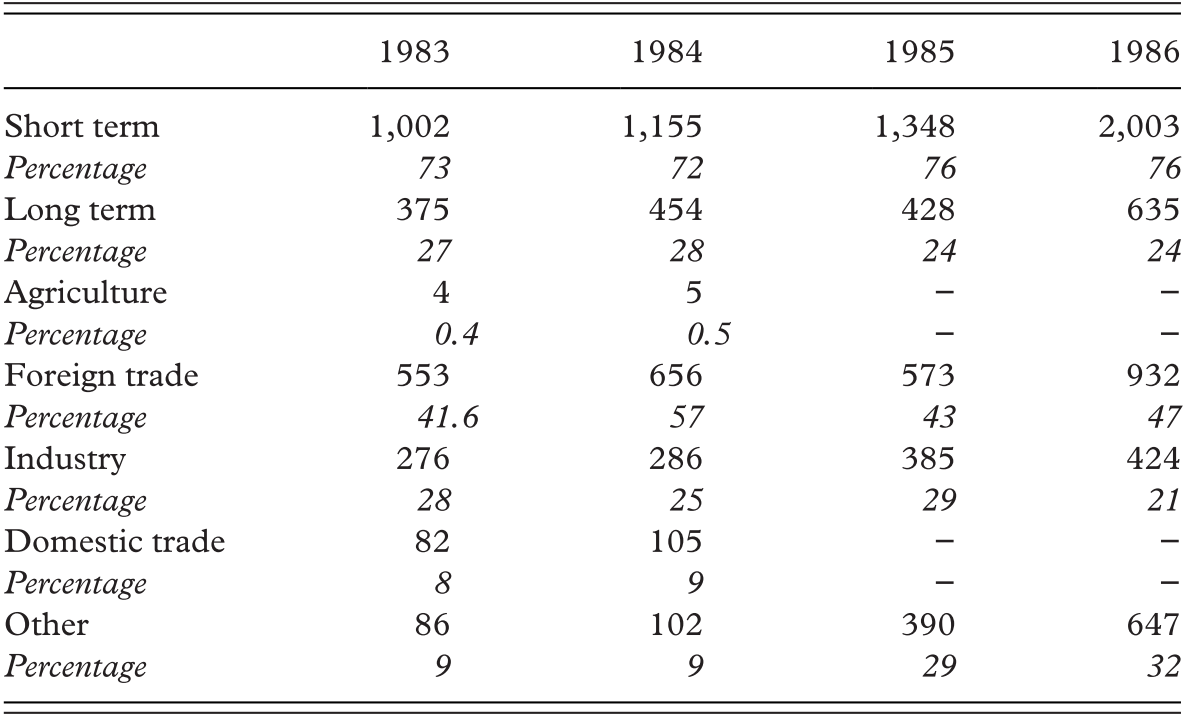

The Islamist elite’s continual efforts to consolidate their regime through their “war” against the black marketers, the implementation of a policy of de-statism (rather than privatization on a competitive basis), and their monopolization of import-export trade earned them the unflattering label of tamasih al-suq (market crocodiles). More specifically, building on gains made from Islamic finance during the oil boom in the Gulf, once in power, the Islamists continued in their efforts to strengthen the resource base of their movement. Indeed, they essentially took over the import-export sector, previously the territory of merchants belonging to the Khatmiyya sect. Indeed, throughout the 1980s commercial bank lending consisted overwhelmingly of short-term loans and remained focused on foreign and domestic trade rather than agriculture and other sectors (Table 5.1). Importantly, lucrative commodities like sorghum were exported through the subsidiaries of Faisal Islamic Bank and the African Islamic Bank, where Islamist stalwarts were senior executives.

Table 5.1 Distribution of total commercial bank lending in Sudan by sector and type of commercial loans, 1983–1986, in SDG 1,000

| 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short term | 1,002 | 1,155 | 1,348 | 2,003 |

| Percentage | 73 | 72 | 76 | 76 |

| Long term | 375 | 454 | 428 | 635 |

| Percentage | 27 | 28 | 24 | 24 |

| Agriculture | 4 | 5 | − | − |

| Percentage | 0.4 | 0.5 | − | − |

| Foreign trade | 553 | 656 | 573 | 932 |

| Percentage | 41.6 | 57 | 43 | 47 |

| Industry | 276 | 286 | 385 | 424 |

| Percentage | 28 | 25 | 29 | 21 |

| Domestic trade | 82 | 105 | − | − |

| Percentage | 8 | 9 | − | − |

| Other | 86 | 102 | 390 | 647 |

| Percentage | 9 | 9 | 29 | 32 |

However, the most important reasons for the regime’s increasingly predatory rent-seeking behavior was that by the mid-1990s the heyday in which Islamic banks were able to capture upward of 20 percent of the remittances of expatriate Sudanese and benefit from a veritable boom in capital investment from wealthy Gulf Arabs had come to an end. By the end of the decade, there was little question that, at least in economic terms, the Islamic banking experiment in Sudan had proved to be a dismal failure. In 1999, in its review of Sudan’s financial sector, the IMF reported that as much as 19 percent of bank credit was nonperforming. Even more devastating, the report further concluded that the Islamic banks had declining deposit bases and credit lending to the private sector (which had risen sharply in the 1980s in relation to other commercial bank lending) had contracted steadily in real terms from 1993 to 1999.16

There were both external as well as domestic political reasons for the failure of Islamic banking in the country. First, the economy in the 1990s was in dire straits as the regional recession deepened and the oil boom in the Gulf ended. The recession in the Gulf resulting from the slump in oil prices in the mid-1980s in particular had vastly reduced the inflow of remittances into the country and officially recorded remittances declined dramatically (Figure 5.1). A chief consequence of the diminution in remittance inflows was that the deposits from expatriate Sudanese into Islamic banks declined resulting in what the IMF observed as a dramatic decline in the capital base of these banks. In addition, the Sudanese domestic economy was in an increasingly weak position. Throughout the 1990s the annual rate of inflation exceeded 50 percent. In the context of a rapidly depreciating currency, commodity prices for cotton also fell just as oil prices were rising. The result was a worsening of the balance of payments and terms of trade. Toward the end of the 1990s, in a last-ditch effort to revitalize the hitherto unregulated financial sector, the Bank of Sudan introduced new restrictions on loans to members of the board of directors and prohibited credit to indebted clients, but this intervention was too little and came too late to save the Islamic banks.

The second reason for the demise of Islamic bank was political. The fact that Islamic banking was essentially utilized by the NIF as a source of finance to expand its patronage network in civil society meant that decisions were often made on political rather than rational-economic grounds. As detailed in Chapter 2, the major shareholders and members of the boards of directors who monopolized the banks’ capital resources were linked to the Islamist regime. This was evident in two important ways. First, the major shareholders and members of boards of directors were linked to the Bashir regime and consequently monopolized the capital resources of these banks. In fact, the shareholders also nominated the members of the boards of directors and appointed the senior management, and so they met few restrictions from within the banks themselves.17

Second, the clients that were favored in the lending patterns of these banks were chosen for their potential support of the Islamist movement and the Muslim Brotherhood organization in particular. The result of this politicization (and Islamicization) of the entire banking system was that, as one important report on the subject noted, these shareholders met few restrictions from regulatory authorities, and few clients felt any pressure to repay their loans at the agreed time. After all, if a chief objective was to recruit supporters to the Islamist movement there was little incentive to “pay back” the Brotherhood-dominated banks in financial terms. Consequently, not only were the Islamic banks short of capital as a result of the diminishing volume of remittance inflows, by the 1990s these banks suffered from very high default rates. This was primarily because of the unregulated environment in which they were allowed to operate by the regime. The central bank, for example, was simply not able to implement regulations on the financial system to limit corruption because they had to come into conflict with shareholders and bank managers with very close ties to the new NIF-backed regime. By the end of the decade it was clear to most Sudanese that Islamic banking was primarily successful in transferring wealth to a rising middle class and elite of Islamist financiers and businessmen. Indeed, by the late 1990s it was abundantly clear that Sudanese were disillusioned with the Islamicization of the financial sector and they no longer put their trust in depositing their money in the Islamic banking system.

It is important to note that many supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood did claim that the Islamic banking experiment was successful in religious if not financial terms. They argued that, after all, their movement was instrumental in converting national banking laws into those that conformed to the principles of shari’a. In reality, however, the mode of operations of the banks tells a different story in that they did not strictly conform to the shari’a’s key prohibition of interest or riba. In particular, the overwhelming use and misinterpretation of murabaha contracts by the majority of the Islamic banks meant that the latter did indeed derive what is often termed a “hidden form” of interest in their lending practices.18 Specifically, rather than fix its profit margin to avoid generating interest (riba) on a loan the Islamic banks arranged a repayment schedule overtime to determine the cost of the loan. As one study noted, the banks secured these loans against liquid assets rather than the physical commodity that is purchased by the client to start his or her business.19 In classical murabaha contracts the lender is supposed to take physical possession of the commodity in case of default rather than demanding security other than the commodity. In the case of Sudan, the record shows that the Islamic banks were more interested in acquiring profits in cash, which contravened the spirit, if not the law, of shari’a.

Significantly, much of the criticism with respect to the operations of the Islamic banks as well as the great wealth amassed by Islamist financers in a short period of time came from within the membership of the Muslim Brotherhood. This criticism was especially strident among the most ardent members of the organization in the campuses of the universities in the capital of Khartoum. The increasingly ostentatious lifestyles of high-ranking members of the Muslim Brotherhood became a source of great debate primarily because it contradicted the discourse that the movement had utilized to recruit new members. By the late 1980s, the Islamist-dominated financial empire that was built in the boardrooms of the Islamic banks gave rise to a veritable transformation of the urban landscape. In particular, the rise of an Islamist commercial class led to a veritable boom in the establishment and expansion of upper-class neighborhoods of al-Manshiyya, al-Riyyad, and al-Mohandesein. These new neighborhoods came to be labeled ghabaat al-asmant al-Ikhwaniyya (the Brotherhoods’ cement jungle) because of the high number of wealthy Brotherhood members who built new mansions in these neighborhoods. These new upper-class areas stood in close proximity to the poorer urban settlements; for many Sudanese this represented a stark contradiction between the populist rhetoric of the Brotherhood which often referenced Khomeini’s discourse of the dispossessed and underprivileged (musta’zafeen) and the realities of a new Islamist bourgeoisie that appeared more intent on securing a lavish lifestyle rather than the call (Da’wa) of Islam. The rapid transformation of the urban landscape in the capital city represented a highly visible image of the social and ideological contradictions of the ascendancy of the Islamists in the country leading many to label the new mansions of the new Islamist bourgeoisie hayaat al-mustakbereen, neighborhoods of the arrogant.

By the mid-1990s just as the Bashir regime had become increasingly unpopular among a wide segment of Sudanese, it was also severally isolated internationally as a result of its support for Islamist militants abroad. The turning point came following Khartoum’s role in the assassination attempt against Hosni Mubarak. In January 1996 the UN Security Council passed resolution 1044 imposing sanctions on Sudan for refusing to cooperate fully with the assassination investigation, and in April 1996, at the prodding of the United States, which still accused Sudan of sponsoring terrorism, imposed even harsher sanctions against Khartoum. Indeed, by 1996 the Bashir regime was deemed a pariah in the international community. International isolation, and the imposition of international sanctions in particular, led to a visible rift between the hard-liners and moderates among members of the NIF. Subsequently, following 1996, Turabi’s influence declined dramatically as Bashir and his inner circle moved to improve their image abroad. Specifically, the Bashir regime dissolved the PAIC, began to cooperate closely with US intelligence on counter-terrorism information, and saw to it that Osama bin Laden exited the country. For his part, on his departure, Bin Laden complained that he had lost more than $160 million after the Bashir regime terminated all his businesses and froze his bank accounts in Sudan.20

In addition, in order to improve its authoritarian image, in 1996 the RCC dissolved itself by passing “Decree 13.” Its chairman, Omer al-Bashir, became president of the republic, and power was formally transferred to the civilian Transitional National Assembly (TNA). The TNA approved the “Charter of the Sudanese People” which defined the functions of the president and the national assembly (majlis watani) and approved the convening of national elections. Two years later in December 1998 al-Bashir signed into law the Political Associations Act that approved the convening of national elections and supposedly restored Sudan to multiparty politics banned since July 1989. In addition, he reorganized the NIF into his new ruling party: the National Congress Party (NCP). Naturally, this meant that the Islamist of the now defunct NIF maintained their dominance in Bashir’s new “civilian” government. The so-called opening up of an electoral process and multiparty politics was no more than a thinly veiled attempt to regain political legitimacy in the face of international isolation and internal dissent. Al-Bashir was elected with more than 75 percent of the vote in the first “elections” in March 1996 and remained in firm control of the military and security apparatus. It was Islamist politics as usual with a government completely dominated by the NIF and its members consisting of primarily young men who had secured the most important positions in the civil service, the military and the government and who did not represent the rest of Sudanese society.

To be sure the introduction of international sanctions against Khartoum in the mid-1990s isolated the Bashir regime both economically and politically, but the crucial shift from a radical to a pragmatic orientation associated with the Khartoum regime’s policies is best understood as a result of domestic economic exigencies rather than foreign policy considerations. Specifically, by the end of the 1990s, as a result of a shrinkage in deposits from expatriate Sudanese, the severe economic consequences of the war in the south, and the end of the boom of Islamic Banking, the NIF regime found itself bankrupt. In the 1970s and 1980s the Muslim Brotherhood were, with the aid of the incumbent regime at the time, able to finance their organization through the monopolization of informal financial markets and Islamic banking. But after a decade in power, the NIF leadership, crippled by a heavy debt and a severe balance of payment’s crisis, turned to another source of revenue to buttress the patronage networks of the Islamist-backed military regime: oil.

From Labor Exporter to Rentier State: The Economic Foundations of Islamist Pragmatism

By the 1990s the consequences of the end of the oil boom in the Arab Gulf, and the attendant decline in remittances as well as Arab financial assistance were reflected in Sudan’s increasingly deep economic crisis. In terms of remittance, in the 1970s and through the 1980s labor remittances did indeed increase dramatically as a proportion of Sudan’s general domestic economy. This is clearly evident in terms of remittance inflows as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP) as well as exports and imports (Figure 5.1). In 1987, for example, remittances as a proportion of GDP increased dramatically from 20 percent to almost 80 percent. Moreover, between 1997 and 1998, remittances again peaked, this time even more dramatically, from 45 percent to almost 140 percent of GDP. However, following 1998, remittances registered a steady decline and by 2009 declined once again to 45 percent of GDP and 22 percent of imports.

However, while remittances continue to represent an important source of foreign currency their continued relative importance in Sudan’s macroeconomy is primarily due to the decline in export revenue over the last four decades. Specifically, what is most notable is the steady deterioration of Sudan’s exports over the course of the 1980s and 1990s. Export revenue minus remittances (i.e., “non-remittance current account credits”) fell from a high level of US 2 billion dollars in 1981 to a low just below US 500 million dollars in 1993. This is the reason why in the late 1990s (during the period with the broadest sustained gap between exports revenue and import costs) remittances surpassed the financial aid (i.e., “net financial flows”) as a source of foreign currency and briefly reached a level equal to total export revenue in 1998 (Figure 5.2). The major economic problem for Sudan in the 1990s was that while the regime was focusing on the financial sector as a source of revenue, commodity exports flattened and dwindled to just above 500 million dollars while imports stayed well above 1 billion dollars for most years. Consequently, as a means of financing these imports, Sudan ran a very high financial debt that, by the early 1990s, had dramatically worsened its balance of payments and crippled the national economy. By the mid-1990s the debt was more than $17 billion, and the annual deficit equaled 25 percent of GDP with hyperinflation running between 80 and 100 percent. A good indicator that showed that the economy was in deep crisis was the steep decline of the Sudanese pound from SL17 to SL500 to the dollar in the summer of 1994, and between 1993 and 2002 there were frequent periods where the country had no foreign currency whatsoever.

Figure 5.2 Sudan’s balance of payments trends with a focus on remittances and deteriorating exports.

In the context of the deep economic crisis in the 1990s, the Bashir regime increasingly sought to hold on to power by developing oil resources in the southern regions of the country. From the perspective of Bashir and his ruling NCP the exploitation of oil in the south was imperative for economic as well as political reasons. On the one hand, within the context of deteriorating exports, a relative decline in remittances, and the diminishing profitability of Islamic banking, Islamist bureaucrats turned their focus increasingly toward the oil sector as a way to sustain their patronage networks. On the other hand, the increasingly fierce southern insurgency was jeopardizing their hold on political power, and most particularly, their hopes of exploiting the oil wealth in the south. Specifically, the NCP understood the need to secure the oilfields and moved toward gaining control of strategic areas in the south by implementing a cordon sanitaire, a task that would be led by proxy jihadist-inspired Mujahideen militias.

However, Chevron – which had acquired oil concessions from Khartoum in the 1980s – had by this time grown weary of revolving military and democratic governments in Khartoum throughout the 1980s and was unconvinced that the NIF would do a better job of suppressing the rebellion in the south. In 1992 Chevron sold its production rights to a Sudanese government-owned company (Concorp), and two years later, in May 1994, the small Canadian company, Arakis, acquired Chevron’s previous concessions and agreed to construct the 1,000-mile pipeline from Heglig oil field in Southern Sudan to Port Sudan. However, in search of more financing, the Sudanese government and Arakis agreed to enter into a partnership with China and Malaysia. On December 2, 1996, the Greater Nile Operating Petroleum Company (GNOPC) was founded consisting of Arakis holding 25 percent interest, China’s CNPC 40 percent, Malaysian Petronas Caragali 30 percent, and the Sudan National Petroleum Corporation (Sudapet) only 5 percent.21

It is China, however – with the most urgent energy demands – that continued to dominate the oil sector in Sudan. It was CNPC that took the lead of the GNPOC in 1997 when the Canadian Arakis sold much of its interest in the consortium. It quickly bought the latter’s concessions, and the CNPC bought a similar commanding share in the Petrodar Operating Company (PDOC) of Upper Nile State. In each of the CNPC’s concessions China maintains the majority share as operator in partnership with the Sudanese government’s Sudapet and other foreign oil companies. In addition to giving CNPC a commanding share of Sudanese oilfields, the Bashir regime developed a close strategic relationship with China. Beijing invested in various economic sectors in Sudan, outside of the oil industry, providing soft loans to Islamist businessmen, and giving Khartoum greater access to military arms. On the political stage, China also frustrated and stalled Western efforts at the United Nations Security Council to apply economic and political sanctions against Khartoum for its violations of human rights in its military campaign against the insurgency in Darfur that began in 2003.

In 1999, with China’s oil giant CNPC in the lead, Petronas and Sudapet completed the construction of the first oil pipeline in the country transporting oil to the Red Sea port for export. At an export capacity of 250,000 barrels a day, oil exportation enabled Khartoum to enjoy its first trade surplus in 1999–2000 when oil exports first went online. Government oil revenues rose from zero in 1998 to almost 42 percent of total government revenue in 2001. Oil exportation vastly improved the balance of payments situation and the impact of the infusion of petrodollars saw the GDP rising to 6 percent in 2003, thanks primarily to the export of oil. Indeed, between 2002 and 2006, Sudan witnessed a veritable oil boom that had an enormous impact on the national economy (Figure 5.3). While in 2002 Sudan’s total revenue amounted to less than USD 2 billion by 2006 the Bashir regime was enjoying upward of USD 8 billion. It was oil, and not remittances, that now financed the bulk of imports into the country and the balance of payments improved dramatically by 2004.

Figure 5.3 Sudan’s balance of payments trends reflecting the change in remittances versus non-remittances sources of revenue.

The oil boom enabled the al-Bashir regime to distribute patronage and bring in formerly excluded social groups into the governing coalition. Just as in the 1970s and 1980s the boom in remittance inflows and Islamic banking enabled Islamist elites to mobilize Islamist commercial networks to buttress their movement; during the mid-2000s oil boom, after a decade of austerity, the Bashir regime and his NCP expanded their patronage network to selectively include a wider group of supporters and bureaucrats while simultaneously excluding Islamic Sufi social groups and networks.

Oil: Boom and Curse

Not surprisingly, during the oil boom of the mid-2000s the state quickly conformed to the general patterns of what is commonly called the “resource curse,” which uniformly contributes to the weakening of state capacity in many oil-export economies. Specifically, with the exploitation of oil resources, Sudan quickly transformed into a “rentier” state and, as a consequence, the Bashir regime faced two central challenges: the building of legitimate institutions and the exacerbation of the civil conflict in the south where the oil concessions were concentrated. Natural resources greatly weaken the capacity of state institutions because governments are able to extract capital without establishing extensive tax or market infrastructures.22 Indeed, the case of Sudan following the oil boom conformed closely to the common observation associated with the “resource course”: that is, that the profusion of natural resources and the inflow of external rents generated from those resources leads to poor and uneven economic growth, flawed governance practices associated with greater corruption, and an escalation of civil conflict and militarization. Furthermore, these trends occur most visibly in countries like Sudan, which possess heterogeneous societies governed by authoritarian regimes that greatly limit political contestation.23

Consequently, while oil revenue vastly improved Sudan’s macroeconomic indicators in the 2000s there was scant reward or benefit for civil society at large. To be sure, there is little doubt that Sudan’s emergence as an oil producer allowed for new claimants to be added to the patronage systems staving off significant dissent and unrest in civil society. However, the pattern of public spending in this period set the stage for greater social and economic inequality and contributed to the emergence of ethnic-based insurgencies in the marginalized regions of the north. On the one hand, the oil boom allowed for the creation of state governments across northern Sudan, putting tens of thousands on the public payroll. Under the austerity programs of the 1990s, government expenditures were less than 10 percent of GDP, but rose quickly to reach 23 percent in 2006, at a time when GDP was growing from 6 to 10 percent annually.24 But although the economy grew rapidly and dramatically (Figure 5.3), the benefits were distributed very unequally. The capital city of Khartoum remained a middle-income enclave, while regions such as Darfur and the Red Sea remained extremely poor and underdeveloped. Indeed, the allocation of services, employment, and development projects by the Bashir regime did not follow the logic of need, but the logic of political weight. In the early 2000s, almost 90 percent of infrastructure spending occurred in Khartoum state, in response to the political leverage of the urban constituency in Khartoum, and the profits to be made from contracting and import-based commercial enterprises. Following the peace agreement signed with the southern rebels in 2005, about 60 percent of development spending went to five major projects, all of them within the central triangle in the north, notably around the Merowe Dam.25

In addition, the lion’s share of the revenue from what was to become a short-lived oil boom was spent on the military. In 2001, for example, military spending was estimated at costing USD 349 million. This figure amounted to 60 percent of the 2001 oil revenue generated from exports, which was USD 580.2 million. According to Human Rights Watch, cash military expenditures, which did not include domestic security expenditures, officially rose 45 percent between 1999 and 2001 and this rise reflected the increased government use of helicopter gunships and aerial bombardment against southern insurgents belonging to the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) in the south.

Oil, Civil Conflict, and the Emergence of the Politics of Ethnicity

By 2005, on the eve of Khartoum’s formal signing of a peace agreement with the southern insurgents of the SPLM that ended four decades of war, Sudan’s transition from a remittance economy into a rentier oil-exporting state effectively altered the nature of the patronage networks of the regime. For a brief time, the oil boom seemed to signal that Bashir and members of the ruling NCP were becoming accustomed to being more secure in office than at any time during their struggle to consolidate power. Indeed, a precarious state of political affairs was set wherein Bashir and his supporters from the security forces would enjoy the support of a rich class of businessmen so long as the state did not interfere in the latter’s pursuit of profits. This meant no political harassment, theological intimidation, and, most of all, inhibiting bureaucratic regulations. The problem, however, was that newly pragmatic leaders in Khartoum came to rely on a narrower base of support than that of the broad Islamist social movements that they cultivated in previous decades. In the context of regional-based rebellions, this development ultimately served to exacerbate the multiple civil conflicts in the country and set the stage for an historic and profound political change: partition.

While the civil war in Sudan has been routinely depicted as rooted in a conflict of national identities between “Arabs” and “Africans,” or a religious quarrel between Muslims and Christians,26 it is best understood as one of several violent disputes between the central state in Khartoum and the regions on the periphery. These include, most notably, the south, the Nuba mountains, the eastern provinces, and the western Darfur region. Indeed, following the Islamist-backed coup of 1989, the Khartoum regime reacted to the various rebellious regional forces with increasing violence, precisely in order to discourage the historically marginalized peripheral regions such as Darfur from rising up in a united front against the central state dominated by a Muslim Arabized riverine elite.27

The eruption of the civil conflict between the south and successive central governments in Khartoum began shortly after independence in 1956. Following a brief experiment in parliamentary democracy, in 1958 Sudan witnessed the first of three military authoritarian regimes, that of General Ibrahim ‘Abbud. Under ‘Abbud, sporadic warfare between the national army and southern guerrillas began in earnest. The fighting outlasted several central governments, both military and civilian. To be sure, the government bureaucracy and the army officer corps have always been dominated by Muslim northerners whose native language is Arabic and who claim Arab lineage, whereas the south is populated by tribes who profess Christianity or animist religions. That is, cultural and religious differences have contributed to the fighting, particularly since Khartoum imposed “Islamic” penal codes in 1983. For its part, the SPLM increasingly defined its identity as African and looked to Sudan’s African neighbors for support and patronage during the four-decade-long civil war. What is noteworthy, however, is that having asserted an African identity by resisting what they perceived as Arab domination, the south set an example for other regions, such as Darfur and the eastern provinces, which similarly demanded equality and a more equitable distribution of power and resources.28

Despite the SPLM’s mobilization of African identity, the core grievances of the south were not only related to issues of cultural identity as such. They also greatly hinged on the issue of the inequitable distribution of economic resources and political power. The promise of oil wealth was a driving force behind the escalation of the conflict and the hardening of interethnic violence in the 1990s.29 Although the primary cause of Sudan’s civil war cannot be attributed to natural resources alone, Sudan’s increasing dependence on natural resources determined the conduct of both the civil war and the negotiations that ended military confrontation.30 Following the discovery of oil, the Bashir regime was keen to ensure that there would be no opposition to its designs to develop the oil economy. In a strategy used later in Darfur to devastating effect, the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), along with armed militias, conducted devastating aerial bombardments against civilians in the oil-rich areas of the south. In addition, because the regime in Khartoum was unable to find willing recruits to join in what it termed a “jihad” in the south, it encouraged ethnic tensions, in effect using local communities in a proxy war. This it accomplished essentially by arming Misiriyya and Baqqara nomadic tribes and allowing them to pillage and destroy the communities of the Dinka and Nuer pastoralists in the south. In the early 1990s, the Bashir regime had expanded its military campaigns against civilian populations in the south and the Nuba Mountains, and this campaign became more deadly as Khartoum began to profit from increasing oil revenues.31

Paradoxically, while the discovery of oil exacerbated the civil conflict in the south it also contributed greatly to the eventual cease-fire and peace agreement between the SPLM and Khartoum. The transformation of Sudan’s political economy is the main reason for the emergence of more pragmatic and less radical politics on the part of the Bashir regime in the mid-2000s. It is also the primary reason that Khartoum agreed to sign a peace agreement with its former adversaries in the south and, moreover, oversee the partition of the country. This change, in what was a self-proclaimed “jihadist” military campaign in the 1990s, was mainly due to the fact that the regime’s governing system and survival was highly sensitive to cash flow. As the state budget expanded as a result of oil exports, the ruling NCP was able to increase its support base and allow more members of the northern elite to benefit, either directly or through dispensing patronage to them. The national budget, which was less than $1 billion in 1999, increased at a dramatic rate after oil exports began at the end of that year, reaching $11.8 billion in 2007. Even more significant than the expansion of its patronage networks in the north, the Bashir regime now realized that they could afford to bring the SPLM into the government following a peace agreement and thereby gain both economic and political dividends from this pragmatic move. It would open up the opportunity for the exploitation and exploration of more oil fields, and furthermore, it would enhance the potential of improving relations with the United States and the opportunity of receiving US refining technology and other forms of foreign direct investment. Consequently, the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement was a direct result of the oil boom and the ways in which it underpinned the increasing pragmatism of a regime still nominally dominated by Islamist elites.

Secession and the Evolving Quest for Patronage Networks: Hamdi’s Arab-Islamist Triangle

If the Islamist project has in many respects disintegrated, its exacerbation of national divisions had grave consequences for Sudan’s national identity and unity.32 On January 9, 2011, in a referendum in the south on the question of self-determination, the people voted to declare independence. The Bashir regime’s willingness (and even eagerness) to oversee the historic partition of Sudan in 2011 remains a puzzle to even some of the most astute analysts of contemporary Sudanese politics. Indeed, South Sudan is the first country in contemporary world history to win independence through peace negotiations, however strife ridden, rather force of arms. There are few governments who would risk such a formidable threat to their sovereignty and political legitimacy as to comply by an internationally supervised agreement that insists on granting an entire swath of territory an “exit option” of this magnitude. In this regard, Khartoum’s implementation of the southern referendum in 2011, as stipulated by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, begs an important question as to why Bashir and his ruling NCP took such a political gamble at the risk of the regime’s survival.

Why did the NCP then risk Sudan’s partition? The answer lies in the fact that the patronage networks underpinning the Islamist-authoritarian regime changed in tandem with Sudan’s evolving economic transition from a labor exporter in the 1970s and 1980s to an aspirant oil exporter in the 1990s and 2000s. Moreover, this structural transformation was accompanied by a marked ideological transformation of the Islamist-backed regime that pragmatically traded in an ideology of global “jihad” in its first decade in power for stability, or rather, for the objective of consolidating political power in the context of increasingly strong insurgencies in the south as well as Darfur. There is, arguably, no individual Islamist who better exemplifies how the state’s patronage networks changed over time than Dr. Abdel Rahim Hamdi. As one of the most influential Islamist policy makers and thinkers of Sudan’s Islamist movement, Hamdi’s own career charts very closely and meaningfully with political, economic, and ideological transformations that have characterized the Islamist-authoritarian evolution of the past four decades. Abdel Rahim Hamdi is a former Islamist financier-turned-investor in an oil company and famously supported southern secession. Hamdi, who, as noted earlier served as Finance Minister throughout most of the 1990s, continued to function as an important economic advisor to the Bashir regime until the latter’s ouster in April 2019. Indeed, he continues to represent the overriding economic outlook of the Muslim Brotherhood leadership in economic affairs, which harbors a decidedly favorable view of neoliberal market reform as part and parcel of the Islamicization of the economy. Hamdi has been an ardent member of the Muslim Brotherhood since he was first recruited into the organization as a student at the University of Khartoum in the 1970s. His career reflects the important ways in which Islamic financial institutions and energy production linked up with the state as an important source of financial patronage. Hamdi, a self-proclaimed student of Milton Friedman33 with a degree from the University of London, was chiefly responsible for accelerating and broadening the country’s privatization program that began in earnest in 1992 under what the regime termed the “economic salvation plan.” Under his guidance and expertise, the state dramatically and abruptly reduced subsidies on fuel and state-owned enterprises. As Hamdi put it at the time: “We have hit the people with horrendous measures, 500 percent increases in the price of bread, a devaluation of 30 percent and they have accepted it. They have seen the government is working in a very sincere way and, more importantly, in a very uncorrupted way, and, therefore, people have accepted it and endured.”34 Significantly, Hamdi, who is also a long-time executive (and shareholder) with al-Baraka Islamic Bank, insisted on holding on to the position as an al-Baraka’s representative in their London-based branch when Bashir appointed him as the Minister of Finance in February 2001. Moreover, in April 1997, he was appointed to the Board of Directors of the Canadian Arakis Energy Corporation (AEC), which was the first to begin oil production in the Sudan following the departure of the American Chevron oil company.

Indeed, Hamdi’s career reflects the important ways in which the state sought to finance its patronage networks as Sudan shifted from a remittance to an oil-export economy. But his ideological orientation also presents an important picture of how the Bashir regime sought to consolidate political power through building state-society linkages along exclusivist social networks grounded in very specific cultural, ethnic, and geographic terms. Indeed, as the extractive and military capacity of the state to both generate revenue and prevent insurgents from launching attacks in the capital diminished, Bashir and supporters of his regime emphasized its Arab cultural character in an effort to revitalize the waning ideological legitimacy of the state. In 2006, Hamdi presented a controversial proposal to the ruling NCP conference that became known as “Hamdi Triangle Dialectics.” The key moral of his thesis was that the Islamists should begin to turn inward and focus on an Arab-Islamic constituency of the “Riverine North.” According to him, this was critical for winning the general elections of 2010 mandated by the CPA and managing its future destiny in the likely event of the partition of the country. In other words, from the perspective of the majority of the Islamists, the division of Sudan should not necessarily be the “natural” outcome of the southern referendum but a result of the Arab-Islamic North’s own choice to secede from the rest of the country. It also reflects an important critique of the majority of the Sudanese opposition in the north which has long located the country’s primary crises as rooted in an exploitative state that perpetuates the dominance of the center on the peripheries such as Darfur, the east, and southern regions. Indeed, it is this vision of an Arab-Islamic “triangle” that represented the Bashir regime’s avenue for political consolidation under the weight of an increasingly bankrupt state battling insurgencies in the outlying regions of the country that guided the high-ranking Islamists in the government before and after the secession of the South Sudan.

The Resurgence of the Black Market and the “Threat” of Democratization

Nevertheless, by the late 2000s, it was clear that the Bashir regime’s efforts to consolidate political power through oil rents following the end of the boom in remittances effectively ended with the secession of South Sudan in summer 2011. Subsequently, the weakened Sudanese pound, high rates of inflation, and rising fuel prices resulted in a resurgence in black-market currency trading that dominated the local economy in the 1970s and 1980s, and this has continued to the present. In a pattern reminiscent of the era of the remittance boom of the 1980s, Sudanese now make regular trips to black-market dealers to buy or sell dollars to take advantage of the difference with the official rate. In response, in a drive to stabilize the exchange rate and curb the expansion of the black market, in May 2012, the central bank licensed some exchange bureaus and banks to trade at a rate closer to the black-market prices. As in previous decades, this was a concerted effort to induce expatriate Sudanese to send more dollars home. But black-market rates stayed higher than the licensed bureaus’ prices. In mid-July 2012 the dollar bought 6 pounds on the black market, while in the licensed bureaus it traded at around 3.3. As one Sudanese financial expert pointed out, “when confidence in a currency erodes, it fuels a cycle of speculation and ‘dollarization’ that makes more depreciation a self-fulfilling prophecy: when you enter this area it is very difficult to escape.”35 In addition to the loss of the all-important oil revenue as a result of the secession of South Sudan, the regime’s financial crisis was compounded greatly by the costly rebellions in South Kordofan and Darfur that sapped state finances, and non-oil sectors like agriculture, long neglected by the Bashir regime’s economic policies, continue to lag behind their potential.

But the real problem was the Bashir regime’s dwindling legitimacy among a cross section of groups and parties in civil society. In June 2012, six years prior to the mass protests that led to Bashir’s ouster from power, and at a time when the attention of the international media was focused on the historic victory of the Muslim Brotherhood’s presidential candidate in Egypt, street protests of a scale not witnessed for two decades erupted in Khartoum and other major cities in Sudan. They began on June 16 with students protesting the announcement of a 35 percent hike in public transportation fees and calling for the “liberation” of the campus from the presence of the ubiquitous National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS). As was the case with the historic December 2018 popular uprising, the catalyst of the 2012 demonstrations was the Bashir regime’s decision to abolish fuel subsidies and the imposition of a wider austerity package that had resulted in a spiraling inflation rate that peaked at more than 30 percent in May 2012.

The June 2012 protests were a direct result of the regime’s economic policy decisions linked to the secession of South Sudan in the summer of 2011. Following years of unprecedented oil exports that fueled economic growth, wherein some years featured double-digit growth figures, the financial basis that had served to maintain the resilience and patronage networks of the regime dwindled overnight. In response, and immediately following the south’s secession, the Bashir regime placed restrictions on the outflow of foreign currency, banned certain imports, and reduced state subsidies on vital commodities such as sugar and fuel. With a budget deficit estimated at 2.4 billion dollars, on June 18, 2012, Bashir imposed another round of more expansive austerity measures lifting fuel subsidies and announced the stringent enforcement of higher taxes on capital, consumer goods, telecommunications, and a wide range of imports.

At the time the Bashir regime argued that the deep economic crisis was beyond the government’s control and that it was, in the words of one NCP member, the result of “malicious traders operating in the informal economy who are smuggling fuel and hard currency at the expense of the Sudanese people.” However, the students, and youth activists that confronted the security forces in the streets of Khartoum, and members of the professional syndicates, and the leaders of the NCF (an umbrella group of opposition parties) argued that the roots of the economic crisis are related to the fact that the bulk of the national budget is allocated to the escalating military campaigns in Darfur and the escalating clashes along the borders with South Sudan that began in earnest in April 2012.

Moreover, at the same time that the regime imposed deep austerity measures in the summer of 2012, the NCP announced the expansion in the offices of government no doubt deeply concerned with sustaining its patronage networks and security apparatus in the context of small but persistent protests calling for the removal of the regime. Ironically, the influential vice president at the time, Ali Osman Taha, blamed the economic crisis on the Sudanese themselves who, as he put it, have been “living beyond their means.” In a country where the majority of families rely on remitting money from expatriate relatives (i.e., Sudanese workers abroad) for their livelihood, Taha publicly stated that the tendency of Sudanese to maintain extended families – where one individual works and ten others rely on his income – is the real reason that local production and incomes are at such low levels.36

To be sure the loss of oil revenue following South Sudan’s secession and the imposition of economic austerity policies inspired the protests in the summer of 2012. Nevertheless, the timing of the protests and organizational strategies utilized therein were clearly related to the protests and transitions in the larger Arab world. In the wake of the Arab uprisings that begin in Tunisia in late 2010, observers of Sudanese politics were near unanimous in declaring that the Sudanese government will “not buckle” to popular protests anytime soon. Indeed, following in the lines of scholars of Arab authoritarianism, these analysts noted that Sudan’s military establishment was beholden to the government just as they have been since Bashir first took power via a military coup in 1989. That is, that the upper ranks of the military are still loyal to his rule, that the formal political opposition is weak and discredited, and that civil society is even more divided than that of Tunisia and Egypt. As one Sudan analyst aptly put it: “[T]here is certainly discontent with the regime, but it’s unclear if enough of the right factors are present to complete the equation in Khartoum [because] protests undertaken thus far have not taken root with a broad section of the population.”37 The influential International Crisis Group similarly argued that “years of subjugation at the hands of the ruling NCP have yielded both political apathy and a weak opposition.”38 Indeed, the wide-scale popular protests of December 2018 came as a surprise to many precisely because the general consensus among analysts was that, in the case of Sudan, the heavy hand of the security services and corresponding fears among the population act to inhibit such a pro-democracy uprising.

The question having to do with whether Sudan will remain resistant democratization then, as now, hinges, on an understanding of factors long associated with the durability of the authoritarian regimes in the Arab world. These include the fact that Arab countries possess weak civil societies, have middle classes beholden to state patronage for their survival, and opposition political parties which are either weak (i.e., Egypt, Sudan) or simply nonexistent. However, as the events in Tunisia and Egypt have shown, none of these conditions precluded the move toward democratization. Indeed, what they have demonstrated is that a weakly organized opposition does not necessarily prevent mass mobilization although it certainly plays a central role as an obstacle to democratic consolidation.

How then can we evaluate the deep popular discontent among Sudanese which resulted in the 2018 popular mobilization calling for yet another period of democracy in Sudan. For the Sudan the answer is relatively straightforward: It lies in the regime’s capacity to maintain a monopoly on the means of coercion. As scholars of authoritarianism have persuasively argued, when the state’s coercive apparatus remains coherent and effective, it can face down popular disaffection and survive significant illegitimacy. Conversely, where the state’s capacity of coercion is weak or lacks the will to crush popular protests, democratic transitions in the Arab world and elsewhere can occur.39

Consequently, in the case of the Sudan, the first key question is, how can we best understand the weakening of the Bashir regime’s capacity for coercion vis-à-vis a resurgent civil society opposition in the lead up to the December 2018 popular uprising in the country? What the examples of Tunisia and Egypt have demonstrated is that the answer to this question depends on the state’s fiscal health, the level of international support, and how entrenched (i.e., institutionalized) the state security sector is in civil society. As in the other Arab countries, taken together, these factors determine whether the level of popular mobilization outweighs the capacity of the coercive apparatus of the regime.

Consequently, the durability of Bashir’s authoritarian regime eventually ended due to a number of reasons. First, the level of international support was extremely low. Indeed, only a few months after southern secession the United States reimposed economic sanctions on the Sudan. In combination with the standing ICC’s indictment of Bashir issued in July 2010, this increased Bashir’s pariah status. More importantly, this diminished any hope on the part of the NCP to generate much needed foreign direct investment and international as well as local legitimacy.

Second, following almost a decade of remarkable growth in GDP (real gross domestic product) averaging 7.7 percent annually, thanks to oil exports, growth declined sharply to 3 percent since 2010.40 The economic crisis was further compounded by a sharp decline in oil-export revenues as a result of the secession of the oil-rich south, deteriorating terms of trade, and minimal flows of foreign investment outside the oil sector. Consequently, the Bashir regime suffered from an enormous scarcity of foreign currency with which to finance spending to shore up its support base. The financial crisis resulted in the imposition of economic austerity measures leading to cost of living protests beginning as early as 2012. Perhaps more importantly in political terms, it also weakened Khartoum’s capacity to suppress dissent since more than 70 percent of oil-export revenue prior to South Sudan’s secession was funneled to support the military and PDF in the country. Third, as witnessed by the protests in Khartoum and throughout the north beginning in 2012, a wide cross section of Sudanese already mobilized in opposition to the regime. In addition, protests – which spread to central Sudan in al-Jazira, Kosti, and the Nuba Mountain region as early as 2012 – were accompanied by cyber activism. In a pattern similar to Egypt and Tunisia, this maintained the link between Sudanese in the country and the hundreds of thousands of Sudanese citizens in the diaspora.

Taken together these factors served to further weaken the capacity of the Bashir regime in ways that could not forestall the call for democratization indefinitely. But the most telling and important reason for the Bashir’s regime’s diminishing authoritarianism was in the fact that the hitherto institutionalized security sector became increasingly fragmented and the top leadership gravely divided. Following the country’s partition, political power became centered on Bashir and a close network of loyalists. Moreover, concerned about a coup from within the military establishment, Bashir purposely fragmented the security services, relied increasingly on personal and tribal loyalties, and the formerly strong NCP party no longer had a significant base of social support even among hard-line Islamists.41 This division was clearly illustrated as early as 2011 by a public dispute between two of the most influential figures in Bashir’s government: Nafie Ali Nafie (presidential advisor and head of state security) who along with Bashir represented the hard-line faction opposed to constitutional reforms and Ali Osman Taha (second vice president) who called for inclusion of some opposition parties to help in drafting a new constitution.

In the shifting post-secession landscape Bashir tried to pursue a two-pronged strategy aimed at reviving the state’s financial capacity and political legitimacy. On the one hand, the regime imposed economic reforms as part of an effort to strengthen the financial capacity of the state by further reducing the state’s role in the economy and already meager public service provisioning. On the other hand, while Omar Bashir routinely insisted on the vigorous reimposition of stricter shari’a legislation, other prominent members of the NCP made strong overtures to the regime’s political rivals in a clear bid to revive the state’s waning political legitimacy among groups in civil society.

This is largely a result of the fact that civil society opposition grew stronger following the partition of the country. Most notably, in July 2012 after two decades of interparty squabbling, the main opposition parties allied under the National Consensus Forces (NCF) signed the Democratic Alternative Charter (DCA) calling for regime change “through peaceful means.” The NCF included the National Umma Party (NUP) of former prime minister Al-Sadiq al-Mahdi and the Popular Congress Party (PCP) led by the late Hassan Turabi, the Sudanese Communist Party, and a coalition of professional associations and labor unions. The NCF agreed on a three-year transition period governed by a caretaker cabinet and a presidential college with rotating chairmanship to rule the country when the NCP’s regime is overthrown. In response, and just days after the signing of the DCA, the first vice president, Ali Osman Mohammed Taha, announced that the government was willing to approach the opposition parties for dialogue on the “alternation” of power. What remained to be seen was whether the Bashir regime would extend this accommodationist stance to the rebel coalition of the Sudanese Revolutionary Forces (SRF). The SRF, the most important military insurgent opposition, includes the factions of three groups from Darfur in addition to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement North (SPLM-N), in South Kordofan, who had been fighting to topple the regime through military means. Nevertheless, it was clear, on the eve of the popular uprising of 2018, that the significant divisions in the ruling NCP party, in combination with the country’s international isolation, the deep economic crisis following the south’s secession, and persistent levels of popular discontent and mobilization were strong indications that Sudan – a country that witnessed two previous popular revolts that dramatically turned the tide of national politics – would find itself drawing important inspiration from its own history as well as its northern neighbors while following its own path and distinctive “Sudanese” trajectory.

Just fall, that is all: Sudan’s 2018 Popular Uprising