Introduction

The notion that individuals have a right to a work-free period at the end of their lives is relatively new. Retirement is an institution that developed largely in the 20th century, as state pensions and occupational pension schemes evolved, and the idea of a fixed retirement age took hold (Kohli, Reference Kohli2007; Sargent et al., Reference Sargent, Lee, Martin and Zikic2013). With increasing longevity, increasing education levels and improved health among the older population, images of what retirement is and ought to be are constantly changing. Sargent et al. (Reference Sargent, Lee, Martin and Zikic2013) have suggested that two general reinventions of retirement are forming: the first involves a continuation of the idea of a distinct life-phase at the end of the working life, but with changes in timing and the activities pursued. The second form implies a rejection of the notion of retirement itself, in favour of an ‘endless’ – if flexible and perhaps downscaled – working life. This ongoing cultural change is complemented by political and institutional changes, most obviously the many pension reforms designed to encourage longer working careers (Ebbinghaus, Reference Ebbinghaus2011; Natali, Reference Natali2017).

This article aims to capture the changing social meaning of work and retirement for a cohort of ‘older’ workers (55–66 years old) in one national setting, namely Norway. The questions we pursue are, how do these older workers think about the transition to retirement (how, when and on what conditions will they retire), and how do they imagine their lives in retirement? Since our interest is in the meaning individuals attach to work, retirement and the transition between the two, we use a qualitative approach. Through an interpretive framework using in-depth interviews with 28 older workers, we examine the ways they talk about work, the considerations influencing their future transition to retirement, and their thoughts on what retirement will look like and how they imagine spending their time once they have clocked out of work for the last time. Older workers in Norway have considerable freedom to design their retirement transition, as we will elaborate below. Norway therefore provides an apt setting to explore these issues.

In what follows, we first give an overview of the literature on the changing meaning of retirement, and on previous studies of meaning attached to retirement transitions. We then present our methods, including an outline of the national context (Norway) and the merits of choosing this particular country as a setting for exploring these issues. Hereafter, the main empirical findings are presented. The article ends with a concluding discussion which links the findings to the existing literature.

Changing meanings of work, retirement and transitions

The position of retirement in the lifecourse has changed in the course of the last generation. This is because, first, life expectancy continues to rise, implying that retirement is by now a significant part of most people's lives. Second, retirement has increasingly ceased to be a homogeneous, age-related experience, and is instead becoming an individual project (Vickerstaff and Cox, Reference Vickerstaff and Cox2005; Furunes et al., Reference Furunes, Mykletun, Solem, de Lange, Syse, Schaufeli and Ilmarinen2015; Kojola and Moen, Reference Kojola and Moen2016). The fragmentation of pension schemes, where workplace-based and individual schemes make up increasing portions of the total package, strengthens this tendency (Meyer and Bridgen, Reference Meyer and Bridgen2008; Grødem and Hippe, Reference Grødem and Hippe2020). Third, ageing itself has become a contested phenomenon: on the one hand, policy makers are increasingly pushing for longer working lives through pension reforms and increased retirement ages (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2019); at the same time, a cultural change is taking place, as older adults increasingly voice expectations of a ‘third age’ of active engagement and new life projects (Laslett, Reference Laslett1989; Moulaert and Biggs, Reference Moulaert and Biggs2012). In short, the relationship between ageing, work and retirement is changing, yet we have limited knowledge about how individuals approach and manage this changing world.

In exploring these issues, we combine insights from the literature on retirement behaviour with insights from scholarship on the changing social meaning of old age, most importantly the notions of a ‘third’ and ‘fourth’ age. In the remainder of this section, we elaborate on the two strands of literature.

The study of retirement behaviour is multi-disciplinary and complex, and tends to discuss factors at the macro-, meso- and micro-level: national pension systems, workplace policies and practices, and individual circumstances and preferences (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Chaffee and Sonenga2016; Topa et al., Reference Topa, Depolo and Alcover2018). The first wave of studies of individual-level determinants of retirement timing were mainly concerned with explaining early retirement, while later contributions have been equally concerned with the question of why some workers remain in the labour market up to, and even beyond, statutory retirement ages (Jensen, Reference Jensenin press). Whether retirement happens early or late, researchers aim to separate between voluntary and involuntary adaptations. Taken together, this makes a classical 2 × 2 table: early/late, voluntary/involuntary. Involuntary early exit has been denoted ‘push’: individuals are pushed out by forces beyond their control, typically lay-offs or health issues. Similarly, voluntary exits are understood as ‘pull’: older workers are pulled in by the attraction of early retirement schemes, or by norms regarding when it is appropriate to leave the labour market (Radl, Reference Radl2012a; Jensen, in press). Factors that explain voluntary late retirement are summed up as ‘stay’ factors, and include work satisfaction and enjoying company of colleagues. The final corner in the table is ‘stuck’ – involuntary late exit. This will occur mainly if workers cannot afford to retire (Radl, Reference Radl2012b; Jensen, Reference Jensen2005, in press).

The neat 2 × 2 table has been disturbed, however, by the introduction of ‘jump’ factors. Jump, like pull, is an explanation for voluntary early retirement, but the factors motivating withdrawal are different and probably more diverse. Jensen described ‘jump’ as

…a voluntary phenomenon, where the decision to retire is not determined by economic incentives, norms or conventions. Rather, and in accordance with current theories of value change, retirement is guided by inner motivations, irresistible impulses, or a desire to realize individual potential in an active third age. (Jensen, Reference Jensen2005: 667)

People who ‘jump’ into retirement typically have plans and new projects they want to get engaged in, be it bridge employment (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhan, Liu and Shultz2008) or entrepreneurship, learning new skills or simply spending time with family. Drawing on theories of the third age (Laslett, Reference Laslett1989), ‘jump’ emphasises that retirement is more than the absence of work; it is a phase of life with new opportunities. ‘Jump’ thus also draws attention away from mechanisms in the labour market, towards individual dreams and fantasies about what retirement will be like, and emphasises individual agency in the transition to retirement.

A number of qualitative studies have explored these issues, and they invariably find a wide variety in how older workers anticipate retirement (Karp, Reference Karp1989; Vickerstaff, Reference Vickerstaff2006; Kojola and Moen, Reference Kojola and Moen2016). These studies leave no doubt that ‘jumpers’ exist: most studies have informants who look forward to retirement. These older workers typically emphasise how they will enjoy their new-found freedom and seek out new experiences: ‘doing many lovely things, reading up a storm’; ‘getting my fingers into everything imaginable’ (Karp, Reference Karp1989); ‘Having more freedom to do what I want and being able to travel more’ (Vickerstaff, Reference Vickerstaff2006: 464). In a quantitative approach, Fouquereau et al. (Reference Fouquereau, Bosselut, Chevalier, Coillo, Demulier, Becker and Gillet2018: online supplement) found that items that loaded on their ‘positive anticipation’ factor included ‘Being able to spend more time with my family’; ‘Being able to relax’ and ‘Being able to control my personal life better’.

Images of retirement are far from always positive, however. Karp (Reference Karp1989) had informants who hoped they would never have to retire. They talked of retirement as ‘social death’, ‘sitting there clipping coupons’ and ‘contemplate my navel’. Karp (Reference Karp1989) interprets such negative attitudes towards retirement as the other side of the coin for professionals who love their job and do not want to leave it. Similarly, Vickerstaff (Reference Vickerstaff2006) sketches four ‘retirement scenarios’, one of them being the ‘don't want to retire’ scenario. Informants in this group are simultaneously happy with their work and afraid of retirement. They were mainly men, and what they feared was those long stretches of free time: ‘What are you going to do when you retire? … An eight or ten hour day is a long time’, as one informant put it (Vickerstaff, Reference Vickerstaff2006: 467). Fouquereau et al. (Reference Fouquereau, Bosselut, Chevalier, Coillo, Demulier, Becker and Gillet2018: online supplement) aimed to identify what their informants typically were afraid of when they retired, and found the following items: (a) losing my energy, (b) feeling depressed, (c) growing old quickly, (d) feeling lonely, and (e) being bored. A much simpler concept of retirement attitudes is employed by Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Van der Heijden and Flynn2017), who base their analysis on responses to the question ‘Are you looking forward to full retirement?’ Based on responses to this question, they found interaction effects between job satisfaction, retirement attitudes and intended retirement age: among respondents in low- and medium-income households, there was a negative association between job satisfaction and retirement attitude. In other words, when job satisfaction rose for these groups, retirement seemed less attractive. No such association was found for higher-income groups. These findings indicate that for low-income groups at least, retirement attitude is essentially a reflection of work satisfaction.

Retirement attitude as a bi-product of work satisfaction is indeed the dominant understanding in all the studies that highlight the ‘staying’ workers who never wish to leave. The underlying understanding seems to be that for some people – most obviously those with a strong work identity – retirement is little more than the absence of the job they love. Some studies, however, hint that aversion to retirement can be seen as an independent factor and not merely the other side of the coin when older workers love their jobs and want to stay. Even people who dislike their job may stay on if they dislike the idea of retirement more. Jensen (in press) suggests the term ‘social stuck’ as an extension of the ‘stuck’ mechanism that typically highlights inability to retire for financial reasons. Individuals are ‘socially stuck’ if they fear isolation in retirement, something he suggests is more likely to happen to individuals who do not have an intimate partner and/or a very small social circle. Other plausible reasons for retirement anxiety can be fear of the loss of status (Barnes and Parry, Reference Barnes and Parry2004), relationship or family issues that can be worsened by retirement, or fear of ageing itself.

Given the recent emphasis on the third age and active ageing, fear of ageing may seem unreasonable and even irrational. Studies of the third age have emphasised contingency, diversity, choice and agency in later life (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010: 121), presenting old age as a state to be embraced rather than feared. Beyond the third age, however, lurks ‘the fourth age’ (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010; Higgs and Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2020). The fourth age is not a distinct phase of life, but a ‘social imaginary’ which ‘[represents] a location stripped of the social and cultural capital that is most valued and which allows for the articulation of choice, autonomy, self-expression, and pleasure in later life’ (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010: 123). The fourth age is ‘real old age … framed by frailty, abjection and the need for care … the collapse of agency and the demise of autonomous identity of the older individual’ (Higgs and Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2020: 1626). Individuals who imagine retirement and ageing in terms associated with the fourth age have every reason to fear the prospect and to postpone the transition.

The notion of ‘jump’ indicates that anticipation of a new life – a third age – has its own appeal in many older workers’ imagination. The literature, however, lacks a concept denoting the potential fear of retirement, and the associated notions of old age, frailty, passivity and social death. Retirement can be imagined as more than the loss of a much-appreciated job, as some workers’ image of retirement may imply ‘collapse of agency’ and the ‘demise of autonomous identity’ – the fourth age.

Having reviewed the existing literature, we argue that the notions of individual agency and motivation are underdeveloped in existing studies. We know little about what attracts ‘jumpers’, or why different ageing workers experience the ‘pull’ of welfare state schemes differently. It is also clear that workers who experience ‘push’ factors, such as health issues or high job demands, can respond in different ways: by grinding their teeth and soldiering on, by approaching the employer and discussing the problem, or by pulling back and retiring. The individual retirement decision is largely a black box (Phillipson and Smith, Reference Phillipson and Smith2005). This contribution aims to illuminate the black box through inductive analysis of qualitative interviews about retirement intentions. In the analysis, we pay particular attention to the previously undeveloped notion of retirement aversion.

Methods, material and analytical approach

The case: Norway

Individual motivations and agency matter more in contexts where older workers have genuine choices with regard to the timing of retirement. This makes Norway a strategic setting for studying these issues. Norway has a very tight labour market, and has had for 20 or more years. Older workers are thus far less likely to be made redundant, and hence pushed into early retirement, than is the case in many other countries. Employment rates among older adult Norwegians are among the highest in Europe: 72 per cent of Norwegians aged 55–64 were in employment in 2018, which is more than 13 percentage points higher than the European Union average (58.7%) (Eurostat, 2019), and only 1.9 per cent of workers aged 55–74 were unemployed by the end of 2019 (Statistics Norway, 2019a: data from the Labour Force Survey). When older workers in Norway wish to remain in employment, therefore, the odds of them being able to make this decision for themselves are higher than in many other countries. The high employment rate can be seen in the light of the general emphasis on employment in Norway, where the inclusive welfare model relies on high employment rates in all groups, including women, immigrants and older workers (Brochmann and Grødem, Reference Brochmann, Grødem, Jurado and Brochmann2013).

Adding to this, Norway implemented a pension reform in 2011, which altered both the state pension (National Insurance) and occupational pensions. The main gist of the reforms was to alter the core logic of the system from defined benefit (DB) to defined contributions (DC). This implies that the new Norwegian pension system removed the old concept of a fixed retirement age, and instead allows for retirement at any point between the ages of 62 and 75. Retirement will happen on actuarially neutral terms, which means that the earlier one starts to draw a pension, the lower the annual amount will be. Flexible retirement on actuarially neutral terms can be seen as a functional equivalent to raising the statutory retirement age. Pensions drawn on actuarially neutral terms are not offset against earnings, which makes it possible to draw pensions and work at the same time. Many older workers, particularly men, use this option (Bjørnstad, Reference Bjørnstad2019).

Prior to the reform, Norway had an early retirement scheme (AFP) that covered all public-sector workers and about 40 per cent of the private sector (Grødem and Hippe, in press. This was renegotiated for the private sector in 2008, making it a top-up pension to be paid on actuarially neutral terms to those covered. Since this reform, all forms of early (from 62) retirement will result in lower annual pensions.

The reform will take full effect for cohorts born in 1963 or later, while cohorts born between 1944 and 1962 have their pensions calculated by a combination of old and new rules. Most of the informants in this study fall into this ‘intermediate’ category, and can thus look forward to more generous pensions than the post-1963 cohorts can expect (for more on the Norwegian pension reform, including the reform of occupational pensions, see Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Fredriksen, Lien, Stølen, Holzmann, Palmer and Robalino2012; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Hippe, Grødem and Sørensen2018; Hagelund and Grødem, Reference Hagelund and Grødem2019).

Average actual retirement ages have increased in Norway since the pension reform, particularly among men in the private sector (Bjørnstad, Reference Bjørnstad2019). Still, they remain below the statutory (in the pre-2011 system) pension age at 67 years. For those who are in employment at age 50, the average age for withdrawal from paid employment was 65.7 years in 2018 (Bjørnstad, Reference Bjørnstad2019). If reducing one's job to 50 per cent is counted as withdrawal, the average age falls by about a year, to just under 65. The highest average is found among academics and people in managerial positions, the lowest is among transport workers.

The Norwegian pension system is relatively generous, and poverty rates among old-age pensioners are generally low (OECD, 2019: table 7.2). In addition, Norway has high rates of home-ownership – about 77 per cent of all households live in a dwelling that they own (Statistics Norway, 2019b). Norwegians also have access to 468,000 secondary homes/summer homes, and about 75,000 persons own property outside Norway – most typically in Spain or Sweden (Statistics Norway, 2019b). These formidable investments provide additional security in old age.

Finally, rates of female employment are high in Norway, but the labour market is heavily segregated by gender. Women disproportionally work in the public sector, typically in health, care and education services (e.g. Østbakken et al., Reference Østbakken, Reisel, Schøne, Barth and Hardoy2017). Occupational pensions are different in the public and private sector, and, generally, they are more generous in the public sector (Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Hippe, Grødem and Sørensen2018; Hagelund and Grødem, Reference Hagelund and Grødem2019). This implies that women in many cases are better protected in old age than men. The high employment rates also indicate that most persons approaching retirement have a partner in the same age range who is also approaching the end of their working life.

Data collection

The pension reform has opened up for a number of different, and flexible, routes into retirement. Workers can retire early or late, and they can combine work and take-up of pension in a number of ways. Our qualitative interviews are part of a larger project where the main interest is in how individuals cope with this new flexibility: the extent to which they are aware of the possibilities, their understanding of the inherent incentives, the financial considerations they make, and their thoughts on their own transition between work and retirement. The interview guide took the ongoing national debate as well as the international literature on retirement transitions as starting points, but aimed to ask open-ended questions inviting the informants’ own reasoning and subjective understandings.

Our analysis is based on 28 qualitative interviews undertaken in October and November 2019. Our selection criteria were: age between 55 and 66 years, having children, living with or having lived with partner, in active employment in the private sector, and – for informants aged 62 and older – combining pension and income from work. The decision to limit the sample to private-sector workers who combined (when they were eligible) work and pension was made to reduce complexity somewhat: we wanted to make sure all informants related to similar occupational pensions, and we wanted to understand their reasoning for exercising the flexibility the new system allows with regard to flexible uptake on actuarially neutral terms. This was important given the overall concerns of the project, but it implies that we have excluded older workers who do not know, or do not care, about the incentives and opportunities in the reformed pension system. Analyses of register data, however, indicate that older workers in Norway now treat pension take-up and withdrawal from work as separate decisions (Bjørnstad, Reference Bjørnstad2019), thus, we do not consider this a serious limitation for our analysis here.

The informants were recruited by the survey institute Kantar, which also performed the interviews on our behalf. Kantar's recruitment section designed Facebook advertisements which invited random users in the right age groups. Interested users clicked a link which took them to a screening form where they could check whether they were in the target group. Those who passed were contacted by telephone, so that the screening information could be verified. Prior to the interviews, informants were given a letter outlining the purpose of the study and their right to opt out at any time, and they signed a consent form. All informants were rewarded with a gift card of NOK 500 (approximately €50).

Interviews took place in Kantar's offices. All interviews began with a short questionnaire, filled in by the interviewer, giving standardised information about gender, age, marital status, employment (full-time or part-time) and the number of children. The rest of the interview was semi-structured and based on a comprehensive interview guide made by the researchers on the team. All the interviews were undertaken by the same person, a Kantar employee, and we had several meetings with him before the interviews started to make sure he understood the purpose of the study. We also watched the four first interviews via live streaming and gave feedback to the interviewer after each session. The interviews were subsequently transcribed by Kantar's transcribers, and transferred to us anonymously. In this way, the anonymity of the informants is very well protected. Nevertheless, outsourcing the interviewing to a third party had both costs and benefits. In this case, we had two main reasons for doing this. The first was that we assumed that outsourcing recruitment to a professional firm would ensure more variety than we might have achieved through other methods. Second, and more importantly, the main topics for the study are the informant's knowledge about the flexible options in the new pension system, and their utilisation of this flexibility. Based on previous studies, we had reason to believe that informants’ knowledge was likely to be scattered, thus we prepared to provide key pieces of information. We did, however, not want the interview to transform into an advice session, thus our interviewer consistently feigned ignorance if informants asked for more detail. This kept the interview on track, while sparing the informants the social embarrassment of displaying their ignorance to a perceived expert. On the other hand, we lost some information when we did not see the informants’ body language, and we did not have the opportunity to adapt the interview guide for follow-up particular topics, etc. Still, we feel that the information lost in this way was not crucial.

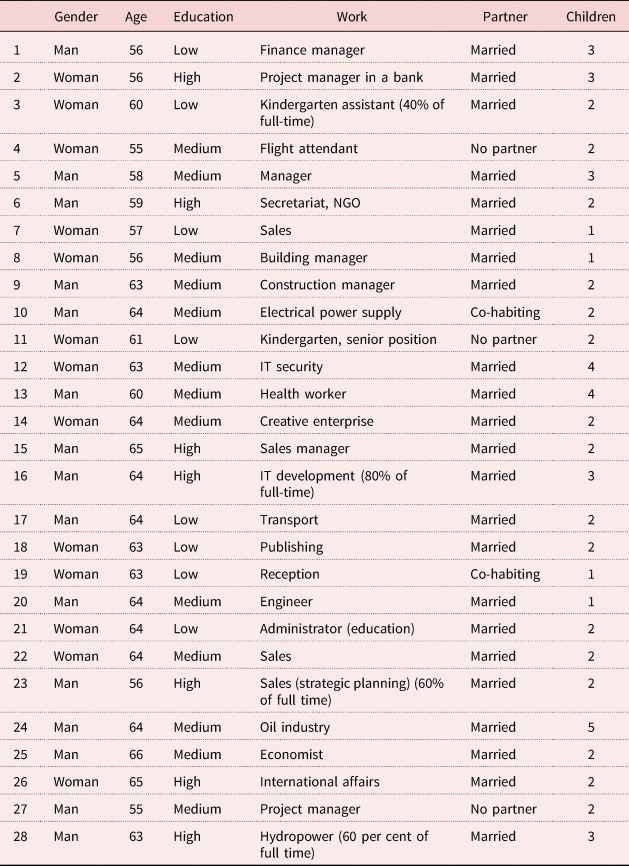

For practical reason, all informants lived in the Oslo region. We interviewed 15 men (age range 55–66, average age 61.4) and 13 women (age range 55–65, average age 60.8). Twenty-three of the informants were married at the time of the interview, two were co-habiting and three lived alone. All were native (non-immigrant) Norwegians. Four worked part-time, while the rest worked full-time. We aimed for an equal distribution of high and low education, but succeeded with this only for women. There are, thus, fewer low-educated men among our informants than we had aimed for. An overview of the informants is given in the Appendix.

Analytic strategy

We approached the interviews from an interpretive framework, aiming to capture cultural meanings and subjective motivations (Weiss, Reference Weiss1994). We started by reading and rereading all the interviews, and identifying the sections where informants talked about their feelings about their job, the conditions under which they would transition to retirement and their images of themselves as retired. We noticed that many informants mentioned their partners when they reflected on these issues, therefore, we went over the interviews again and identified systematically what the informants said about their intimate relationships. Having reorganised the material, we developed a set of descriptive open codes to capture the concepts and emotive statements informants used to talk about their jobs and images of life in retirement. Open descriptive codes were then combined into analytic codes around the major themes. The analytic codes were abstractions from the descriptions and inspired by the existing literature. The emphasis on agency emerged through the analysis rather than as a result of specific questions asked.

There were three topics we, based on existing literature, expected would be important, yet turned out to play a small part in the informants’ considerations. These were financial concerns, health concerns and parents’ care needs. Generally, when asked open questions, our informants talked a lot about choices and less about constraints. This may be specific to the Norwegian context: the Norwegian economy has prospered for some time, which has allowed the cohorts that are currently approaching retirement to build up considerable nest eggs. Similarly, the finding that none of our informants feared being forced out of their job due to reorganisation or cuts must be understood in the light of the tight labour market in Norway in recent years. Care services for children and the elderly are well-developed. That our informants were middle-aged or ‘young old’, and still in employment past the age of 55, may have allowed them to brush off our open-ended questions about health. ‘You never know, of course, but I have no particular cause for concern’, was a typical response. This setting implies that findings cannot be generalised to national contexts characterised by less well-organised labour markets, fewer welfare services and more old-age poverty. Given our interest in subjective images of retirement transitions and retired life, it is, however, beneficial to choose a setting where the majority of older workers feel that they really have genuine choices.

Results

Our interviews revealed a variety of approaches to work and retirement, and to the timing and form of the transition between the two. We were struck in particular with how the informants talked about what they found ‘meaningful’, and how they reasoned around the manoeuvring space they had and their changing relationships with their employers, managers, colleagues and family members. Through the analysis, we developed three ideal-typical approaches to the work–retirement transition, which we have called ‘the logic of deadline’, ‘the logic of negotiation’ and ‘the logic of retirement aversion’. These three logics are ideal-types, and serve to reduce the complexity in the material. While some cases were hard to define, most of our informants could quite easily be sorted into one of the three categories.

The logic of deadline

One ideal-typical category was those who had set a deadline for when they would leave, or at least start downscaling, working life. Some in this category were vague with regard to whether they wanted to quit working at a given age, or if this was the age when they imagined downscaling and working a bit less, others were adamant that they would be leaving. Some wanted to leave their jobs as early as possible – at 62 – others had a later deadline, but none of them planned to work beyond the age of 65. What set them out as ‘deadliners’ was their attitude towards retirement: none of them were interested in negotiating terms for working longer. They typically responded disinterestedly when the interviewer brought up options of job adaptations and downscaling. Instead, they talked with enthusiasm about their plans for retirement.

None of the informants in this group were exhausted or felt unable to do their jobs anymore, but they often felt that their working life had run its course, or that the job just was not what it used to be. They felt they had done enough (to use the concept from Vickerstaff, Reference Vickerstaff2006). Notably, many in this group emphasised that the job used to be easier, but reorganisations or increased demands for efficiency had increased their workload to a point where they could not see themselves doing it in the future:

I have always enjoyed going to work; the company has grown so that in the 12 years I have been there we have more than doubled both our activity and the number of employees. The economy section has not grown at the same pace, so my workload has increased. I enjoy a high pace, but it has become a little too high recently. (Man, 56, basic education, works as a finance manager)

I'm super-happy at work. I have the best job in the world … But when I started, we travelled and had stop-overs in different countries, and this job was very, very different … We worked far less, shorter days, and had much longer resting periods. And higher wages. (Woman, 55, college education, works as a flight attendant)

A third informant, a woman working in a nursery, emphasised how staff cuts had made her job harder, mentally and physically, over time. She longed for ‘more staff and smaller units, as we had a hundred years ago when I started’. These informants not only felt that they had done enough, but that their jobs and work environment were moving in the wrong direction, and they did not see a future for themselves there in the longer term.

These narratives came from informants in jobs that did not require higher education. About half the deadliners, however, had higher education. Their motivations for setting a deadline to employment were different. One woman put it succinctly. She spoke warmly of her job, then continued:

On the other hand, how should I put this … the autonomy, that is, that feeling of self-determination or freedom, really, the feeling of being in charge of your own life, that will become weaker if there are too many job demands … And then I think, at one point I am kind of done with that. (Woman, 56, university degree, works in a bank)

She, too, had ‘done enough’ in her present job. Her vision was to retire at 63 and go on to work for a humanitarian organisation. This she wanted to do, not for the pay, but for the sense of purpose. Such visions were widespread among the college-educated informants who had set a deadline for employment and started to vision themselves as retirees. The higher-educated typically planned to upgrade their skills – computer programming was mentioned, as well as learning new languages – and strikingly often they talked about doing voluntary work. A 58-year-old man was open to ‘working in a kindergarten as kind of a grandpa, or substitute teacher in a school’; a 64-year-old man imagined ‘chopping wood for the elderly’. The college-educated informants talked with enthusiasm about such prospects, but it still seemed clear that the activities they imagined were less important than the sense of autonomy, the freedom, they expected to gain. They wanted to contribute, and they imagined it would do them good to remain active, but they did not want a new set of demands or a new schedule.

The lower-educated deadliners, too, spoke with enthusiasm about their plans for retirement, but were less likely to envision skills upgrades or voluntary work. Typically, they mentioned travelling, some of them dreamt of escaping Norwegian winters by spending a few months every year in a warmer climate. Their travelling plans were, however, relatively modest: all of them emphasised that they would not be able to fund lavish dream holidays. Spending time with family, grandchildren in particular, was another popular option, particularly among women.

Practically all the deadliners talked about retiring with their partners. Typically, they looked forward to creating a new life, with more leisure and more autonomy, with their partners – indeed, most of them discussed the timing of their retirement in terms of when their partners would retire, and in many cases, this is what defined their deadline.

The financial incentives inherent in the pension reform had made little impression on the deadliners. They knew they would lose money by retiring early, but the lower annual pension did not worry them. Many of them emphasised that they were good with money and preferred a frugal lifestyle anyway, others had savings or investments on which they could draw. Time and autonomy were in any case more important than money, they maintained.

The logic of negotiation

A different ideal-typical approach was ‘the logic of negotiation’, represented by the informants who expressed that they would continue to work ‘for now’ or up to a certain point, and then consider.

The negotiators stood out from the deadliners in that they were open to discussing the timing of their exit from work. Some of them had already reduced their working hours, and thus were already in dialogue with their employers about necessary or desirable adaptations (similar to the findings in Furunes et al., Reference Furunes, Mykletun, Solem, de Lange, Syse, Schaufeli and Ilmarinen2015). Generally, the negotiators were ambivalent about their jobs: all of them expressed that they enjoyed the work and the social environment, yet there was almost always a ‘but’: high stress levels, physical strain, some unpleasant tasks, sometimes having to work with sub-optimal teams. The negotiators appeared to be in a more or less constant inner dialogue about the pros and cons of their job:

Some days I'm just fed up. When I'm out driving. Maybe I'm heading far out in the sticks, and then meet a person who is all grumpy, and I have been driving for several hours and … aaaargh, is it worth it? So then I think, now I quit. But then I'm curious too, and I want to see results. So … Other days work is fun, and I think to myself I can't quit yet, not until I have been fed up for a long period. So, it's a rollercoaster. (Woman, 64, college education, works in sales)

Negotiators seemed to enjoy the sense of autonomy that the ability to ‘vote with their feet’ offered:

Yes, that is important, I have to say; if you get involved in a project you are dissatisfied with, I am in the situation where I can simply quit, right. (Man, 63, college education, works in construction)

I don't feel [stress] much. And that is probably related to, as I mentioned, I'm practically unsackable. I have extreme seniority, and have done everything, really. (Man, 63, university degree, works in hydropower)

All the negotiators were aware that their pension would be higher if they worked for longer. Most of them talked about this as a bonus rather than as a main motivation, but it clearly played some role in their decision-making. For some, the allure of a higher annual pension was balanced to some extent by other financial considerations. For instance, some informants pointed out that the sooner they retired, the sooner they could sell the house and move to a cheaper location away from the Oslo region.

Health considerations played a minor role in the informants’ ongoing inner negotiations. Some of them had already reduced working hours for health reasons, but only one imagined that her deteriorating health would effectively be the trump card in her negotiations. This informant – a 60-year-old kindergarten assistant – was already 60 per cent retired on disability pension. She was happy to work two days a week, but anticipated that her deteriorating health would force her into full retirement at some point. She was the only negotiator who seemed to assume that her transition into (full-time) retirement would be subjected to circumstances beyond her control (i.e. push factors). All the others seemed confident that this transition would be determined by their own preferences and priorities.

One major difference between negotiators and deadliners is that the former are much less likely to talk with enthusiasm about what they will do when they retire. The deadliners had new projects they were eager to get started on, whether those were related to self-development or social activities; the negotiators talked about retirement in different words:

Nah, you probably need some new projects, then. So you don't just, like, loaf around. (Man, 56, university degree, works in sales)

Sure, when I retire, we will have more opportunities to, perhaps, travel and such, but at the same time, I'm like, something in me just protests at the thought of staying home every day. (Woman, 60, low education, works in kindergarten)

Negotiators felt the need to find something to do after retiring, but they did not have new projects lined up, or clear dreams for what they wanted to achieve, like the deadliners typically did. Most of the negotiators were married, but unlike the deadliners they were typically not planning to co-ordinate their exits with their partners. Some of them had working partners, and retirement was not something they discussed. Others had retired partners, but did not feel the need – or any pressure – to join them. In short, the negotiators appeared job-centred. Their decision to stay in employment hinged on for how long they find their jobs interesting and rewarding, while it was also informed by the incentives structures in the new pension system.

The logic of retirement aversion

The third ideal-type we identified was ‘the retirement averse’. Informants in this category typically harboured a deep ambivalence towards the prospect of retiring. They were approaching retirement age, but they all communicated that now is not the time. Typically, they were very fond of their jobs:

No really, I have a passion for what I'm doing, I think it's fun … I was probably one of the first girls in this country who [did this job] … I'm not sure I have any negatives to bring up. (Woman, 63, college education, works in information technology (IT))

Yes, because it's really pleasant … It's a nice place to work, a creative environment … it's my dream job, simple as that. (Woman, 64, college education, works in creative enterprise)

The job is great, it's interesting and intellectually challenging … the working environment is just superb and the colleagues are great. Everything is just ace, I have nothing to complain about. (Man, 65, university education, works as sales manager)

Each of these quotes identify the informants as stayers: they find work rewarding, and have good relations with managers and colleagues. Still, other sections of the interviews with these informants suggested that there was a darker side to their cheerful stayer attitude. The way these retirement averters talked about retirement ranged from mild anticipation via disinterestedness to outright dread. It was the latter sentiment that set them apart from the other two groups. The following quotes are representative:

When I think about that I should retire, I panic … I see that society puts those who are retired in their own box. I don't want to be in that box. (Woman, 65, university degree, works with international affairs)

I can't stand sitting at home, I'm terrified of sitting at home and watch TV. So I need a plan … No, I'm terrified I won't bother to get up early and will sit around in my nightgown and watch TV. Or Netflix, or such… (Woman, 63, college education, works in IT)

…you easily sleep until 9 am and then breakfast isn't over until 10:30 with Facebook and everything, and then half the morning has passed so I don't get started with anything until the afternoon … It feels meaningless. (Man, 64, college education, works in engineering)

No, but I can be brutally honest, since you don't know my husband. I don't want to become like him. Because he says it himself – ‘do you not see how I deteriorate?’ And I do see that, because he's become such a homebody. I have almost given up getting him out of the house … And I'm not going to be … it's just so easy to just remain sitting there. (Woman, 64, college education, works in creative enterprise)

‘Panic’, ‘terrified’, ‘meaningless’ and ‘deteriorate’ were thus concepts many averters used to describe their prospects for retirement. This dread seemed to go beyond the fear of boredom that has been identified in many studies, and they also go beyond Jensen's (in press) notion of ‘socially stuck’ due to a fear of social isolation in retirement. These informants were educated people with interesting jobs, they had partners and friends, and they were aware of all the options that exist for people who stay at home during the daytime. Still, they harboured a deep ambivalence against retirement, rooted in fear of ending up ‘just sitting there’ – sleeping in, not bothering to dress, deteriorating. It is worth emphasising that the 64-year-old woman with the ‘deteriorating’ husband emphasised that she loved the man and enjoyed his company most of the time. It was not retiring and having to be around him all the time she feared, she feared that she might gravitate towards becoming like him in retirement: deteriorating, a homebody. The first quote, from the woman in IT, adds a second layer to this: her fear was that she would face the stereotyping of the elderly, ‘that box’, so that she would no longer be considered an interesting and knowledgeable part in conversation. Neither deadliners nor negotiators expressed such sentiments.

It should be emphasised, still, that these averters did not regard passive old age as an inescapable fate. Most of them would also talk about activities they would engage in and social relationships they would nurture. ‘Just sitting there’ was a risk they would have to work consciously with themselves to avoid, in the absence of the structure the working day provided. Finding new activities was not just about filling time, as it seemed to be for the uninterested negotiators, but an urgent need in order to avoid the attraction they imagined the couch might have on a retired person.

One of the interviews, with a 60-year-old man we classified as an ‘averter’, stood out. The informant knew practically nothing about the pension system, and he had given very little thought to retirement. During the interviews, he took long breaks to think before giving short answers. At the very end, he was asked if there was something he wanted to add. The informant thought for several seconds, then said ‘when you reach retirement age, then you are old, I have thought’. If he refused to think about retirement, it seemed to follow, he did not have to be old.

Contrary to what the notion of ‘socially stuck’ would imply, all our retirement averters lived in partnered relationships. Only one of them, however, talked about co-ordinating exit with the partner when the time came. All the others talked about retirement as a decision that they would make independently of their partner. This was true whether the partner was retired or still working. Partners still played a role in their decisions, but only indirectly: some of our informants let us understand that there were issues in their relationship that they feared would be exacerbated by retirement. One informant explained that he and his wife had different wishes for retirement: she wanted to travel; he preferred to stay at home. His desire to work, at least part-time, can be understood as a strategy to limit travelling without having to tell the wife that he did not want what she wanted. Another informant, a 60-year-old man, communicated that retirement was almost taboo in his house, that this was not something he discussed with his somewhat younger partner. ‘She was severely ill some years ago, and she sees that she may need to retire early. But that's a conversation that's kind of… (trails off, laughs)’. For this couple, thinking about retirement implied thinking about her frail health, which was not something they wanted to do.

Discussion

Based on interviews with 28 older workers in the private sector in Norway, we have proposed three ideal-typical approaches to the work–retirement transition: the logic of deadline, the logic of negotiation and the logic of retirement aversion. While this is obviously a simplification of the variation in the material, we believe these ideal-types capture essential dimensions of the variation among older workers. We arrived at these ideal-types through analysing informants’ responses to open-ended questions, in a way that was informed by previous literature on how older workers approach retirement.

Most previous studies of retirement behaviour have focused on retirement decisions as motivated either by work-related factors (often denoted as push/stay/stuck factors) or by images of retirement (pull/jump factors). Our starting point has been that the decision to quit/downscale work and the decision to enter retirement is one decision – or a series of decisions – that researchers should ideally study as a whole, with attention to agency and motivation. Our ideal-types add some nuance to the push/pull/stay/stuck/jump grid, as we discuss in this final section.

Our deadliners can be seen as classical jumpers, with their bubbling enthusiasm for the new projects on which they will embark. They used words like ‘autonomy’, ‘self-determination’ and ‘freedom’, and talked about how they would learn new skills, nurture social relations and engage in voluntary work. Far from fearing ‘the collapse of agency’ (Higgs and Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2020), they viewed retirement as a phase where they would have autonomy more than ever. They clearly saw retirement as a third age (Laslett, Reference Laslett1989). However, deadliners are typically also engaged in an active process of disengagement from their jobs, as evidenced in how they emphasise recent negative changes. Like Vickerstaff's (Reference Vickerstaff2006) informants, their story is that they have done enough: their job is changing, they are getting older, it is time to move on. They appear to have arrived at that this conclusion rather passively, as none of them mention approaching their managers to discuss a reduction in workloads, a reduction in working hours or other measures to make the situation at work more appealing; nor have their managers, or anyone else in the workplace, initiated such conversations. The deadliners, in effect, have forsaken their agency in the workplace, and their managers appear to do little to revitalise them. These processes at the workplace – where older workers disengage and forsake agency, and their employers tacitly let them – can be understood as a subtle form of push. Our deadliners are not forced out by lay-offs, health problems or discrimination, but gently guided out the door by implicit, unquestioned age norms (Radl, Reference Radl2012a).

Those who approach the retirement transition through the logic of negotiation, on the other hand, assume a high degree of agency at work. ‘I can't quit until I have been fed up for a long time’; ‘If I'm not satisfied, I can simply quit’; ‘I'm practically unsackable’ – those are the (slightly revised) words of negotiators. Negotiators are at an age, or rapidly approaching an age, where they can chose to retire, but they do not have to. Rather than disengaging and fixing their eyes on the opportunities of retirement, like the deadliners do, the negotiations treat this circumstance as a source of empowerment at work. The existence of an exit has given them a stronger voice, to use Hirschman's (Reference Hirschman1970) concepts. Negotiators have no fears about retirement, but they are not particularly enthusiastic either – they seem essentially disinterested in retirement. Some of them have exercised agency in the workplace by downscaling working hours or moving to a less-demanding position. In this way, they have made their working life more enjoyable, and they intend to stay employed for the foreseeable future (see also Furunes et al., Reference Furunes, Mykletun, Solem, de Lange, Syse, Schaufeli and Ilmarinen2015).

As we would expect from the existing literature, those who plan to retire late – sometimes as late as possible – all speak enthusiastically about their jobs, and often are very attached to their work role. In established terms, they are stayers. Almost all studies find that those who are attached to their work roles imagine retirement as a phase of boredom and empty days (Karp, Reference Karp1989; Vickerstaff, Reference Vickerstaff2006; Kojola and Moen, Reference Kojola and Moen2016). In our interviews, we have identified a sense of dread that seems to go beyond fear of being bored – a deep ambivalence or even aversion to retirement. The informants who follow the logic of aversion – healthy, educated workers with active social lives – pictured themselves in retirement sitting in their nightgown in front of the television, day in and day out. This sounds like an image of depression more than boredom. The way some of our active informants imagine that once they retire, their bodies may be taken over by an old person who never manages to get off the couch, is striking. It dovetails with what Gilleard and Higgs call the ‘social imaginary of the fourth age’: ‘…a fear of passing beyond any possibility of agency, human intimacy, or social exchange’ (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2010: 125; see also Higgs and Gilleard, Reference Higgs and Gilleard2020). Passing beyond any possibility of agency seems to be precisely what these informants fear.

The difference between how some informants view retirement as a phase where they will finally gain agency (‘being in charge of your own life’), while others view it as the potential loss of even the possibility of agency (‘it's so easy just to remain sitting there’) is striking. A qualitative design is not well-suited to drawing conclusions about cause and effects, but we have identified two issues that are worth examining further in later studies. One is related to the quality of the informants’ relationships with their partners. For deadliners, retirement was typically a joint project for themselves and their partners. They discussed their plans with their partners and shared an enthusiasm for embarking on this new phase of life together. Averters were less likely to talk about their partners at all, and when they did, they often revealed potential tensions in the partnership or frustrations about their partners. Issues linked to partnership seem to go beyond preferences for timing of retirement, and deeply affect the respondents’ sense of agency in old age. The other key issue is related to the sense of agency in the workplace, and the subtle ways in which employers and employees may in effect collaborate – implicitly – to ease the older worker out of employment. This seemed to be happening to some of our deadliners in particular, who talked about how their workplace had ‘changed’. Instead of exercising agency in the workplace in the wake of these changes – talk to their manager, downscale or move to a less-demanding role – they disengaged and poured their energy into planning for active agency in retirement. Notions of ‘push’ and ‘jump’ seem too crude to capture such adaptations, which probably develop over time and in ways that are highly sensitive to subtle signals from managers and co-workers towards older workers. In short, future research should aim at developing more-nuanced understandings of how feelings about the workplace and anticipation of retirement are intertwined, change over time, and are embedded in subtle negotiations with employers, co-workers and families.

Finally, the ambivalence that some informants in this study express towards retirement is thought-provoking. Rather than being merely a mirror of positive feelings towards work, this ambivalence appears to be rooted in the fear that it will be difficult to maintain a sense of meaning, agency and social status outside paid employment. It may be that this mind-set must be understood in the light of the Norwegian context, where employment rates are high and the normative lifecourse centres around employment for both men and women. To what extent this ambivalence is found, and how it manifests, in different countries will be a matter for future research.

Acknowledgements

The article is written as part of the project ‘Coping with flexibility. Behavioral adaptations to the new pension system and their consequences in a lifetime perspective’. We thank our colleagues in the ‘Coping with flexibility’ project, Axel West Pedersen and Elin Halvorsen, for useful discussions on the selection criteria for participants and the interview guide for this study. Our sincere appreciation to the older workers who took part in the study, and our thanks to the reviewers for their helpful comments on a previous version of this paper.

Author contributions

Both authors contributed to all phases of the study and the article, and approved the submission of the article.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway (grant number 270874/H20).

Ethical standards

The project is approved by NSD data protection services (reference number 753280).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix: List of informants