‘ … Dowland to thee is deere, whose heauenly tuch

Vpon the Lute, dooth rauish humane sense:

Spenser to me, whose deepe Conceit is such,

As passing all conceit, needs no defence.

Thou lou’st to heare the sweet melodious sound,

That Phoebus Lute (the Queene of Musicke) makes:

And I in deepe Delight am chiefly drownd,

When as himselfe to singing he betakes … ’Footnote 1

‘VVHilst vitall sapp did make me spring,

And leafe and bough did flourish brave,

I then was dumbe and could not sing,

Ne had the voice which now I have:

But when the axe my life did end,

The Muses nine this voice did send’.Footnote 2

Towards the centre of a small anthology of 20 poems about love, published in 1599 and attributed on its title page to none other than William Shakespeare (1564–1616),Footnote 3 a verse is found which meditates briefly on the interrelationship between ‘Musicke and sweet Poetrie’ (see the first of the above extracts). Paying homage in its 14 lines to two celebrities of the Elizabethan musical and literary worlds – John Dowland (1563–1626) and Edmund Spenser (1552–99) – and simultaneously reflecting on the close marriage between poetry, singing, and the lute, there can surely be no clearer symbol of the status which this musical combination had attained by c.1600. By this time, the lute had also cemented its reputation as the ‘Queene of Musicke’: it was mentioned in countless contemporary texts, often linked to famous musical figures from antiquity like Amphion and Apollo, and it was even sometimes described in a quasi-religious manner (as a former tree that had acquired a divinely bestowed musical voice in its ‘afterlife’, like in the second extract above by Spenser). Indeed, over the 25-year period of its peak (1597–1622), some 30 different lute song collections appeared in print, amounting to a total of more than 600 songs.Footnote 4 After eventually falling out of fashion by the 1630s, this repertory was once again brought to public attention by Edmund Fellowes (1870–1951), whose editions of The English School of Lutenist Song-Writers from the 1920s onwards provided the impetus for further scholarly research and helped secure the lute song’s continued presence in modern times, both in commercial recordings and the popular imagination at large.Footnote 5

Yet despite the wealth of scholarship dedicated to this repertory, the types of voices for which it was probably intended has received surprisingly little attention to date.Footnote 6 In some respects, this may seem inevitable, since any attempt to establish precise parameters is confronted by the truism that no Elizabethan or Jacobean voices survive and also, as the influential French writer Pierre de La Primaudaye (1546–1619) observed, ‘we seldome see that the speaking and singing of one resembleth the speech and tune of another’.Footnote 7 Furthermore, singing was a social phenomenon that traversed all strata of English society, and evidence for lute accompaniment occurs quite frequently within this complex web of singing practices, both in amateur and professional music-making.Footnote 8 Indeed, the earliest surviving English lute music, such as Royal Appendix 58 (after 1551) and Stowe 389 (1558), both held in the British Library, shows a strong connection to the voice via tablature accompaniments to popular songs and solo versions based on them.Footnote 9

The general lack of scholarly interest in the voice types associated with the Elizabethan and Jacobean lute song has nonetheless acquired fresh significance in light of recent research challenging the plausibility of the falsetto voice in this period. In 2015, for example, Andrew Parrott re-examined evidence previously assumed to document the countertenor or falsetto voice in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century sacred vocal music, concluding that terms like ‘fausset’ or ‘falsetum’ had been misunderstood and that modern vocal pitch had also fuelled misinterpretation of the notation.Footnote 10 In the previous year, Simon Ravens published a chronological investigation of the falsetto voice (from the Ancient Greeks through to the twentieth century) that also considered aspects like human physiology alongside national and cultural vocal stereotyping. As a result of these independent publications, both scholars concluded that falsetto singing seems not really to have been used in Medieval and Renaissance vocal music.Footnote 11

Yet in spite of this, the idea persists that the lute song was ‘composed in the style of the professional, courtly, countertenor male voice’, which was ‘fashionable throughout the period and commonly developed among male vocalists’.Footnote 12 Focussing primarily on the printed lute song collections alongside relevant literary, archival, and iconographical evidence, this article will therefore attempt to refine current knowledge of the performance of this repertory via consideration of the following: (a) an investigation into the instruments used, their tunings, and evidence for transposition; (b) an analysis of the music itself, including the part names, clefs, and melodic writing; and finally (c) an examination of literary, documentary, and musical evidence for the tenor and the falsetto voice and their respective connections to the lute song. The combination of these different research areas collectively indicates that this repertory was primarily conceived for instruments in fixed tunings, with women and children singing the song melodies in the written treble register and men singing them in the octave below in tenor register.

Instruments and Tunings

Before discussing information relating to singing in late Tudor and early Stuart England, it is worth clarifying the instrument(s) which accompanied the lute song. The title pages and music of the printed collections indicate several possible performing forces, including multiple singers (up to six voices), tablature for lute or orpharion, and additional or substitutional bass viol or lyra viol (or occasionally ‘viols’). Two further printed music books with tablature add six more songs: four with bandora and two with cittern accompaniment (see Table 1).Footnote 13

Table 1. Instrumentation in the Printed Song Collections with Tablature

Note. The number after the composer’s name indicates the relevant songbook (i.e. ‘Dowland i’ = John Dowland, The First Booke of Songes).

This Table excludes Richard Allison, The Psalmes of Dauid in Meter (London: William Barley, 1599) and Robert Tailour, Sacred Hymns Consisting of Fifti Select Psalms of David and Others (London: Thomas Snodham, 1615), since these are not, strictly speaking, collections of lute ayres, even though they were also printed with tablature.

a Instrumentation listed relates only to the songs with tablature included in these collections; i.e. it excludes other pieces that some of these books also contain, such as unaccompanied madrigals, songs with viol consort, instrumental pieces, etc.

b The table includes the songs with bandora in William Barley, A Nevv Booke of Tabliture, iii (bandora), hence why it starts a year before the first printed collection of lute songs.

c Where instruments are named in the music, internal title page or preface (rather than on the main title page)

d Title pages of songbooks that specify ‘viols’ in the plural.

A careful examination of the lute tablature reveals that it is primarily intended for the ‘meane lute’ in g′, tuned g′-d′-a-f-c-G (Image 1a to 1c). Since the orpharion (Image 2) had identical tuning to a mean lute and could thus read the same tablature without affecting the pitch of the voice and viol parts, it is unsurprising that it also appears on certain songbooks as a suggested substitute for the lute.Footnote 14 Although largely ignored in modern lute song performances, the orpharion may actually have been the preferred choice of accompaniment for some contemporaries; for example, John Aubrey (1626–97) posthumously recorded his grandfather’s praise for Sir Carew Raleigh (c.1550–c.1625), who apparently ‘had a delicate cleare voice, and played singularly well on the olpharion (which was the instrument in fashion in those dayes), to which he did sing’.Footnote 15 Yet could these songs have been accompanied by differently tuned lutes as well?

Image 1a Anonymous Italian (?Venice) (c. 1630), 11-course Lute with ebony and ivory inlay (Museum No. 1125-1869) (© The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), London, with permission). No English lutes survive from the period.

Image 1b Anonymous English or Northern Italian (c.1590–1600), Betrothal painting on a copper panel (© Derek Johns Private Collection, with permission).

Image 1c Isaac Oliver (c.1565–1617), Female figure playing a lute (c.1610), ink drawing, The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust) (© The Courtauld, with permission).

Image 2 Francis Palmer (London, 1617), Orpharion, Collection of Musikmuseet, Musikhistorisk Museum & Carl Claudius’ Samling, Copenhagen, Denmark Inv. No. CL 139 (© Arnold Mikkelsen, CC-BY-SA, The Danish Music Museum / The National Museum of Denmark, with permission).

A bass lute in d′, tuned d′-a-e-c-G-D, could theoretically have been used instead of a mean lute to suit a lower voice, although this was surely not ‘common practice’.Footnote 16 Bass lutes are in fact explicitly named only very rarely in surviving English nobles’ and gentries’ wills and inventories of the period (see Appendix 1a). Collectively, the largest proportion of this information shows typical ownership of only one lute, whilst references that do not follow this trend normally document ownership of only small numbers, that is, between ‘ij Lutes’ and ‘4 lootes’. Clearly, multiples on their own cannot be assumed to indicate contrasting sizes and tunings, irrespective of the possibility that they may have differed from one another in reality – a point which can be usefully emphasized via comparison with other instruments where variations in sizes and tunings seem unlikely, such as the ‘iij lutes’ with the ‘iij bandoraes’ in Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester’s (1532–88) inventory at Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire (c.1578) or the ‘Lutes viii’ with the ‘Vyrgynalles paires v’ in the inventories (1596–1609) of John Lumley, First Baron Lumley (c.1533–1609) at his various residences in Surrey, County Durham, and London.Footnote 17

Similarly, with virtually no exceptions,Footnote 18 listings that mention lutes alongside songbooks or other ‘lewting books’ provide no details regarding the instrument’s size and most likely relate to typical (i.e. ‘meane’) lutes, like the 1608 will of Godwin Walsall, Hebrew lecturer at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge University, which simply records ‘a lute & a lute case’ alongside ‘Dowlandes songes in 2 volumes. sticht’ and ‘benetes songes in 4. partes. 4o sticht’.Footnote 19 In addition, only a miniscule number of literary sources connect the bass lute to solo song, and no English iconography convincingly substantiates this practice.Footnote 20 It seems that the bass lute was primarily used in lute consorts, like ‘the three lutes’ at court in which Robert Johnson (c.1583–1633) and Philip Rosseter (1568–1623) both variously played bass lute (see Appendix 1b), and in larger ensembles with other instruments, like those heard in the 1607 ‘Maske’ in honour of the marriage of Sir James Hay (c.1580–1636), First Earl of Carlisle to Honoria Denny, daughter of the Earl of Norwich.Footnote 21 Indeed, printed lute songs which explicitly stipulate a ‘base lute’ are exceptionally rare (just two out of more than 600 songs).Footnote 22

This situation is also similar for lutes in other tunings and sizes. Although other lute tunings existed on the Continent,Footnote 23 it is clear that, for contemporary English lutenists with any knowledge of musical notation and theory beyond tablature, the term ‘lute’ generally indicated an instrument with the top string solmised as g sol re ut.Footnote 24 In turn, the word ‘meane’ generally appears only where it was necessary to distinguish it from the ‘base’ lute.Footnote 25 These observations are confirmed by analysis of other contemporary English lute music, such as the surviving corpus of lute duets (c.1570–1610), which are almost always for ‘two Lutes tun’d alike’,Footnote 26 save a small number for mean and bass lutes (i.e. tuned a fourth apart) and a tiny handful of Continental pieces for two lutes tuned a tone apart, mostly copied from prints of Pierre Phalèse (1510–73).Footnote 27 Similarly, despite its misleading name, the ‘treble lute’ in the English mixed-consort music of Thomas Morley (1557/8–1602) and Rosseter was actually intended for a mean lute in g′ (‘treble’ perhaps simply hinted at the way its part was dominated by high fret positions, often on the treble string).Footnote 28

In addition, English evidence for the theorbo – which could theoretically act as a substitute for the mean lute in g′ due to its tuning – suggests that it was not really used or even widely known during the heyday of the lute song. Although this instrument was apparently first brought to England c.1605 by Inigo Jones (1573–1652), it is mentioned in very few sources pre-1620, and it also appears to have been seen as distinctly Italianate.Footnote 29 Indeed, only one English literary text apparently describes its use to accompany a solo singer and, significantly, this occurs within a deliberately Italianate context; likewise, the only surviving music printed in England pre-1620 to stipulate a theorbo is a collection of monodies and canzonettas by the Italian composer Angelo Notari (1566–1663).Footnote 30 Theorboes are also very rare in surviving English inventories and other documents until after 1630,Footnote 31 even though one is depicted in the portrait by John de Critz (1551/2–1642) of Mary Sidney, Lady Wroth (1587–1652) from c.1620 held in Penshurst Place.

Lastly, the viol required in these collections appears variously as ‘viol de gambo’, ‘base violl’, or simply ‘viol(s)’ (Image 3). These words are used interchangeably, and there is nothing to suggest that they indicated anything other than an instrument in standardized tuning; indeed, some books explicitly stipulate a bass viol ‘tunde the Lute way’, that is, its normal tuning of d′-a-e-c-G-D (the tuning of the tenor viol matches that of the mean lute in g′).Footnote 32 The lyra viol is also occasionally called for in the lute song books, yet this is not so much a distinct instrument from the bass viol as an alternative manner of playing, using tablature to accommodate chordal accompaniment and different tunings – a point exemplified by the second book of songs (1601) of Robert Jones (fl. 1597–1615), which includes two options for the bass viol part: the normal bass line (‘the base Violl the playne way’) and a chordal part written in tablature (‘the Base by tableture after the leero fashion’).Footnote 33 Only later on was the lyra viol possibly a distinct instrument in its own right.Footnote 34

Image 3 John Rose (active 1552–61), Bass viola da gamba c.1600 (accession number 1989.44) (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET), New York, with permission).

Significantly, the written pitch of the bass viol part clearly supports the use of a mean lute in g′ (or an orpharion): indeed, only four songs out of the entire printed corpus under consideration have viol and lute parts in different keys, and the wording on two of their respective title pages provides a simple solution to this apparent problem by calling explicitly for lute, orpharion, ‘or’ bass viol.Footnote 35

Transposition

Having clarified the lute and viol intended in this repertory, it must briefly be investigated whether contemporary musicians ever transposed lute songs to suit their own pitch preferences. At this time, lute- and viol-sounding pitch was not standardized and partially depended on optimal tensile strength of strings.Footnote 36 However, it seems that pitch may not have varied as widely as is sometimes claimed, and much evidence also survives of lutes playing in ensembles where they had to play to a given pitch.Footnote 37

English lutenists certainly used transposition, for it is discussed in the English version of the famous lute treatise by Adrian Le Roy (c.1520–98), a work which was even cited in the Varietie of Lute-lessons (1610) by Robert Dowland (c.1586–1641).Footnote 38 Yet Le Roy’s treatise is of suspect relevance for the lute song. Firstly, he discusses transposition of music for solo lute, not lute with other musicians; secondly, he transposes music written in mensural notation – French chansons by Orlando di Lasso (1530/32–1594) – not music written in tablature; and thirdly, despite writing for those ‘without great knowledge of Musicke’, his apparently easy method includes errors in the transcriptions.Footnote 39

Despite this, the survival of some lute songs in versions using different keys could seem to provide indisputable evidence for transposition, at least in certain cases. A good example is ‘Flow my Teares’ (or ‘Lachrimæ’) by John Dowland, which exists in a five-part instrumental arrangement in the same key as the original song (A minor), a setting for mixed consort a fourth higher (D minor), various solo lute versions written both in the original key and a tone lower (A minor and G minor respectively), and also a setting for bandora (C minor).Footnote 40 However, the overwhelming majority of printed lute songs do not survive in such versions; furthermore, rather than indicating possible options for the singer, those few examples of songs that survive in different keys generally suggest that this instead reflected the choice of performing forces (i.e. vocal or purely instrumental).Footnote 41 Transposition of the tablature likewise necessitated rewriting it out, but the small number of surviving examples of songs in different keys raises doubts over the frequency of this practice.

In addition, a tiny handful of printed lute songs have tablature in a different key and pitch to the melody it accompanies (see Table 2).Footnote 42 These songs therefore do not work if performed as written: seven examples occur in Robert Dowland’s A Mvsicall Banqvet (1610) alone. Several similar examples also exist in certain manuscript sources such as the ‘Dallis Manuscript’, Trinity College Dublin, MS 410/1 (c.1583) and British Library, Additional Manuscript 4900 (c.1604).Footnote 43 Yet all these instances can be explained simply through a general desire to avoid ledger lines or too many accidentals in the written vocal part.Footnote 44 The lutenist presumably played the tablature on a mean lute in g′ rather than retuning or playing another (differently tuned) lute to match the written vocal pitch in these rare cases; the singer thus inadvertently transposed to fit the lute in these few instances, since this was clearly the simplest (and, by proxy, likeliest) solution.Footnote 45 It therefore seems that lutenists utilized transposition only in specific cases and thus probably did not transpose lute song tablature on a regular basis, if at all.

Table 2. Lute Songs in the Printed Collections (1597–1622) with Pitch Disparity between Voice and Lute Tablature

Note. The data assume the use of a mean lute in g’ for the lute tablature in all pieces. Theoretically, the use of a bass lute in d’ resolves the pitch disparity in Campion’s The Third and Fovrth Booke of Ayres, iii, song 10; and Mason & Earsden, The Ayres that vvere svng and played, songs 7 and 9. However, this solution seems unlikely since it would in turn imply that the remaining pieces in the table also require differently tuned lutes, which is problematic in terms of (a) the miniscule total number of pieces that fit those apparent tunings, (b) the lack of stipulation for such lutes in the respective songbooks, and (c) the lack of evidence for lutes in such tunings in other English sources.

With the exception of those few songs just discussed, where a musical analysis makes it clear that the singer had to transpose to fit the lute, written evidence that discusses vocal transposition has similarly questionable application to the lute song. Indeed, music instruction manuals such as The pathvvay to Musicke (1596) generally mention this practice in relation to ‘plaine song’.Footnote 46 This term means a simple melody, like a metrical psalm tune, and it also frequently occurs alongside the word ‘descant’, in other words indicating a tenor or ground upon which polyphonic music is based.Footnote 47 Discussions of vocal transposition therefore do not relate to songs accompanied by instruments, particularly those reading from tablature.

There is also nothing in the voice parts of the lute songs that particularly suggests transposition possibilities. For example, an F3-clef or even a C4 or C3-clef in the bass part of around 40 of the printed lute songs could initially imply chiavette clef combinations (indicating downwards transposition, typically by a fourth).Footnote 48 However, this reading is at best unlikely and in reality unconvincing, since comparison of all the songs in the books where a chiavette song seems to occur actually reveals that the written cantus ranges do not differ substantially from one another, if at all. A notable exception is John Dowland’s A Pilgrimes Solace (1612), which contains eight songs with bass parts in F3-clefs and high cantus parts, but the chiavette solution is problematic here for several reasons.Footnote 49 Firstly, a bass lute would be required for these potential chiavette songs, but nothing in the book suggests this (it calls simply for ‘the Lute’) – surely an oversight given the apparent rarity of such instruments. Secondly, Dowland’s other lute song books (including those with F3-clefs) do not convincingly employ chiavette, so their use in A Pilgrimes Solace would be difficult to explain; the same is true of the other lute song books produced by the printers linked to A Pilgrimes Solace.Footnote 50 In fact, the eight songs in question are no higher if performed as written (reaching up to g″ or a″) than a large number of other songs in the printed lute song collections. In any case, the practice seems to have been used in England primarily in sacred, not secular, music.Footnote 51

It therefore seems that, rather than transposing, one was instead expected to ‘learne quickly in what cléefe you should take your part’.Footnote 52 Indeed, two of the printed lute song books state that they were written for ‘all the partes together, or either of them seuerally’, clearly suggesting possible solo use of any voice part (irrespective of whether this was primarily a marketing ploy or not).Footnote 53 The lute song repertory thus seems to have been printed in a format which was intended to facilitate instant performance. This links more generally to a culture of music-making in which one could ‘in short time […] sing a difficult song of himselfe, without any Instructor’,Footnote 54 an attitude exemplified by Edward Herbert, Lord Baron of Cherbury (1582/3–1648), who claimed that during his undergraduate days in the 1590s, he had ‘attaind also to sing my part at first sight in Musicke, and to play on the Lute with very litle or almost noe teaching’.Footnote 55 The lute song books themselves likewise occasionally speak directly to an amateur reader.Footnote 56 Thus, in short, there seems little reason to doubt that the obvious solution was the one intended by the composers and printers of the lute songs.

Voices and the Lute Song: Evidence from the Music

The combination of all the evidence presented above regarding different instruments, transpositions, and pitch possibilities raises important questions in relation to the sung melody, since it seems most likely that these aspects were considered to be reasonably fixed. What, therefore, does this tell us about the voice(s) that sang this repertory?

The title pages, prefaces and dedications in the lute song collections give almost no clues regarding the intended voice(s); they simply state that it is music ‘to sing’ (or ‘to be svng’) or instead stipulate a ‘voyce’ (or, where applicable, ‘voyces’) (Image 4a and 4b). The only three exceptions to this – Vltimvm Vale (1605) by Robert Jones (c.1577–1617), the Fvneral Teares (1606) by John Coprario (c.1570–1626), and A Booke of Ayres (1606) by John Bartlet (fl. 1606–10) – all indicate a ‘treble voice’ or ‘two Trebles’.Footnote 57 An additional hint is provided by Coprario, who also mentions a ‘mean part’ which ‘may be added, if any shall affect more fullness of parts’, yet interestingly, this ‘mean part’ is called ‘alto’ in the music itself.Footnote 58 These ‘treble’ and ‘mean’ stipulations probably refer primarily to boys’ voices,Footnote 59 even though the word ‘treble’ was also sometimes used to describe a female voice.Footnote 60

Image 4a Philip Rosseter (1568–1623) and Thomas Campion (1567–1620), A Booke of Ayres, Set foorth to be song to the Lute, Orpherian and Base Violl (London; Peter Short, 1601), title page (British Library, Music Collections K.2.i.3.) (© British Library Board, with permission).

Image 4b John Danyel (1564–c.1626), Songs for the Lvte, Viol and Voice (London; Thomas East, 1606), title page (British Library, Music Collections K.2.g.9.) (© British Library Board, with permission).

Just like ‘treble’ and ‘mean’, the words ‘cantus’ and ‘altus’ are also linked more generally to children.Footnote 61 Judged on evidence from contemporary literary sources, it seems that the boys who sang such treble and mean parts could have been aged up to 14 or 15 years old and were expected to have ranges from around a, b, or c′ up to g″ or a″, which perfectly suits the treble and mean range ‘cantus’ parts in the lute song collections.Footnote 62 Although still relatively uncommon today,Footnote 63 performances of lute songs by boy trebles were clearly more widespread c.1600, as substantiated by references in literary sources, noble correspondence, state documents, and also stage productions, particularly those of the children’s drama companies.Footnote 64 Alongside descriptions of a character like a pageboy singing to a lute or viol, as in two plays by Nicholas Breton (?1545–?1626),Footnote 65 boys also played female characters, as documented explicitly in VVhat Yov VVill by John Marston (1576–1634), where the schoolboy Holifernes Pippo was granted leave ‘to play the Lady in commedies presented by Children’.Footnote 66 Unsurprisingly, some of those plays performed ‘by Her Maiesties Children, and the boyes of Paules’, like John Lyly’s (?1554–1606) Sapho and Phao (1584) and Marston’s The Dutch Courtezan (1605), also included a female character who ‘singes to her Lute’.Footnote 67

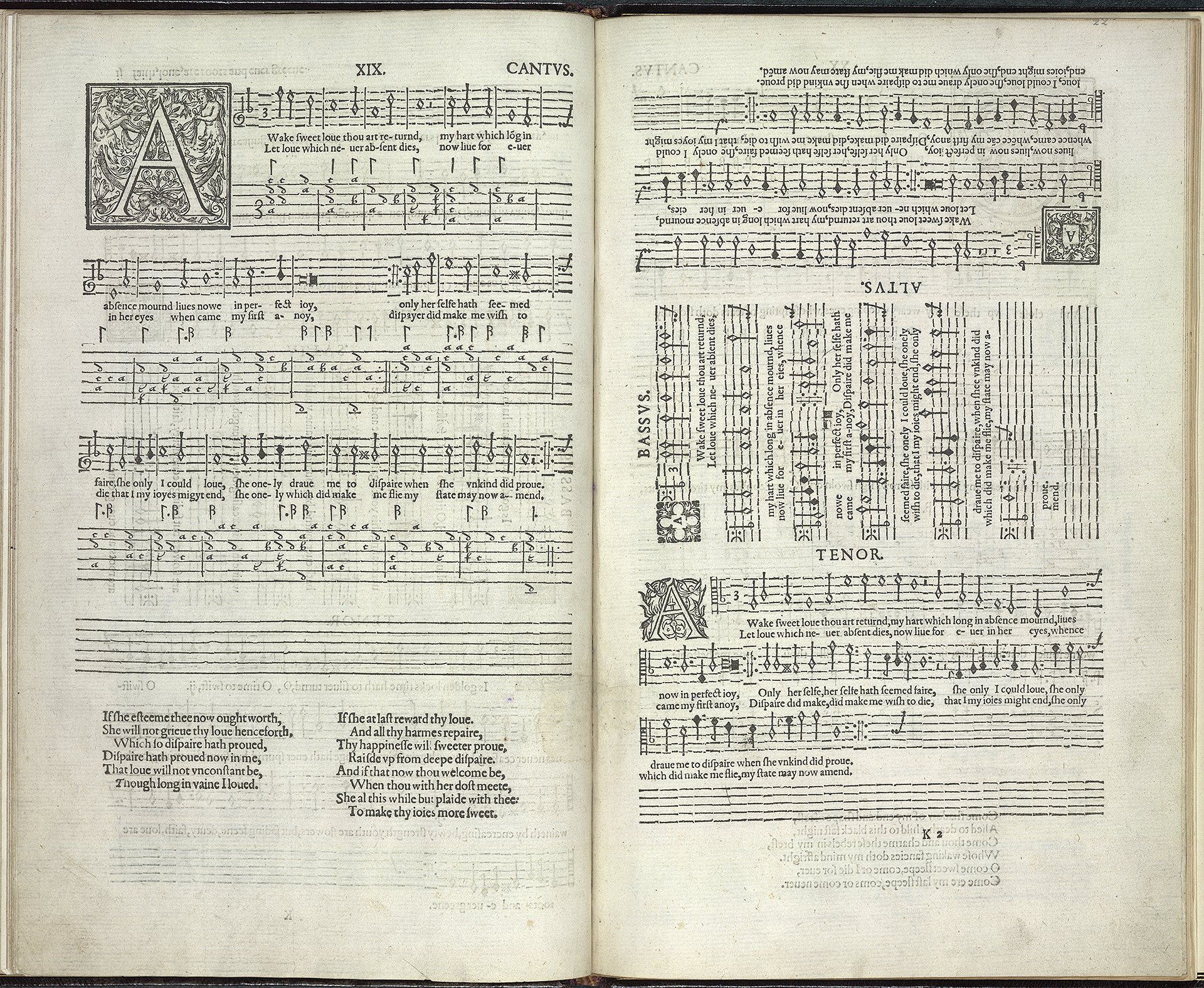

Turning to the inside of the songbooks and the music itself, the part designations do not really elucidate further the question of the intended voice(s) (Image 5). What at first glance appears to be a correlation between the names ‘cantus’, ‘altus’, ‘tenor’, and ‘bassus’ and their modern choral counterparts turns out to be rather less clear-cut; indeed, it quickly becomes apparent that these names primarily indicate the hierarchical relationship of one part to another rather than the assignment of each part to an exact vocal type and range.Footnote 68 For example, a number of the songbooks include songs with ‘cantus’ and ‘altus’ ranges and clefs that are virtually or even completely identical to one another, such as ‘Sweet was the song’ by John Attey (d.c.1640), where both the ‘cantus’ and ‘altus’ parts use a G2-clef and have a range of e′ to a″, or ‘On a time in summers season’ by Robert Jones, where both parts use C1-clefs and have a range of d′ to e″.Footnote 69 In contrast, other songbooks have ‘altus’ parts that are decidedly ‘tenor-like’ in register and also exhibit terminological fluidity between part names, as exemplified via comparison of three songs by Thomas Campion (1567–1620): ‘Vaine men whose follies make a God of Loue’ (‘altus’, C3-clef, range d to f′), ‘Harden now thy tyred hart’ (‘contratenor’, yet with identical clef and range as the former example), and ‘Now hath Flora’ (whose ‘Tenor part’ is written in both C2 and C3-clefs with range d to g′).Footnote 70 Similar instances between ‘tenor’ and ‘bassus’ parts could likewise be highlighted; for a pertinent example, compare the ‘Basso’ of ‘What delight can they inioy’ (C3-clef, range d to g′) by John Danyel (1564–c.1626) with the ‘Tenore’ of another one of his songs, ‘Now the earth’ (C4-clef, range c to e′).Footnote 71 More significantly, in some of the collections for solo voice, like the two books of ayres (1610 and 1612) by William Corkine (fl. 1610–17), the word ‘cantus’ is routinely applied to the texted melody irrespective of its actual written pitch and clef (which sometimes extends down to c and uses a C3-clef).Footnote 72 Thus, whilst it would be wrong to claim that the part designations in these lute song collections are completely arbitrary or that they are so broad in application as to be totally meaningless, it is also clear that they are not intended to indicate a precise vocal type or range. Indeed, it is perhaps worth highlighting here that the words ‘cantus’ and ‘altus’ generally seem not to have described a voice type (‘treble’ and ‘mean’ were typically used instead).Footnote 73

Image 5 John Dowland (1563–1626), The First Booke of Songes or Ayres of foure partes with Tableture for the Lute (London; Peter Short, 1597), song 19 (sig.Kv-K2r): ‘Awake sweet loue’ (British Library, Music Collections K.2.i.4.) (© British Library Board / Bridgeman Images, with permission).

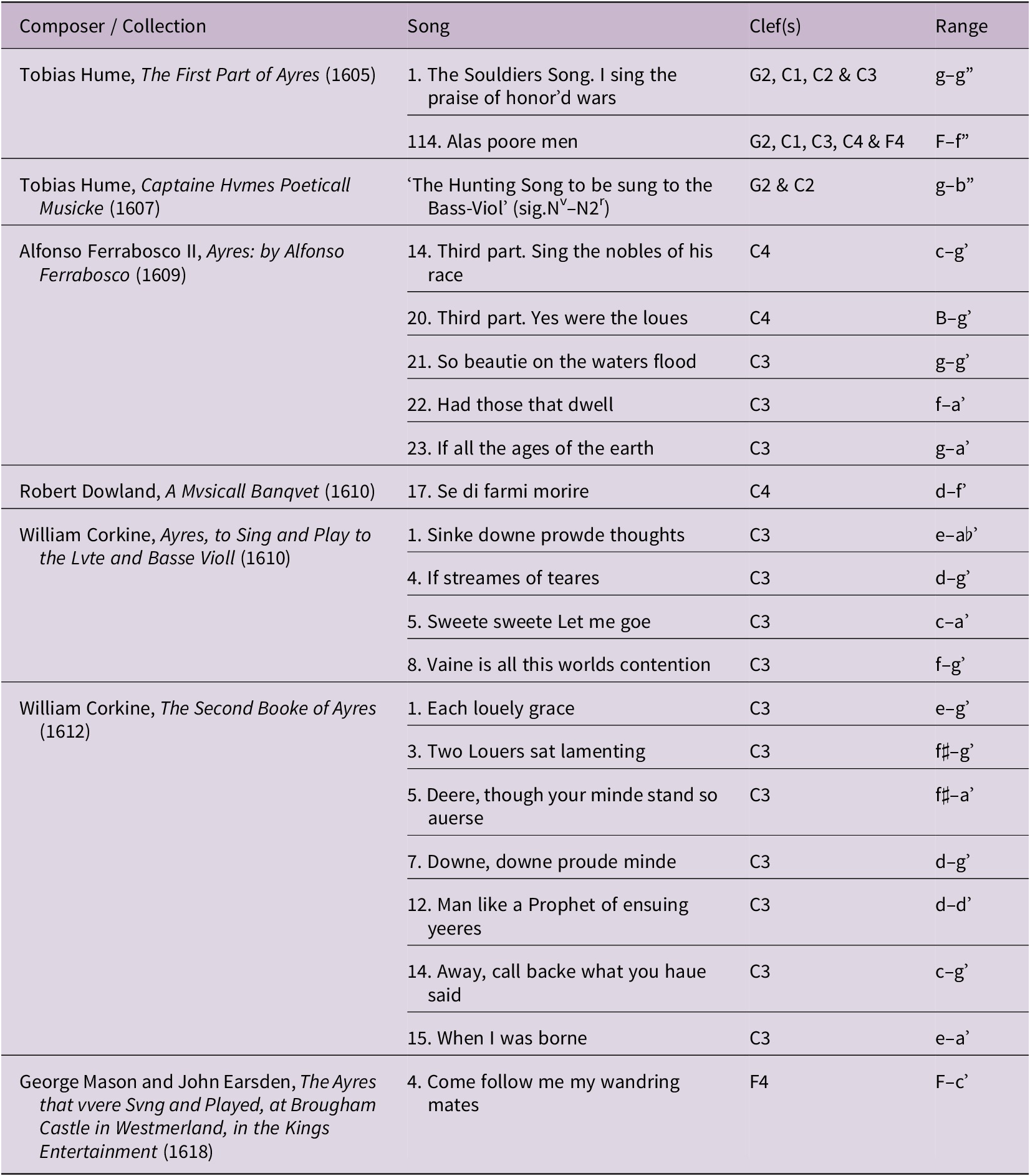

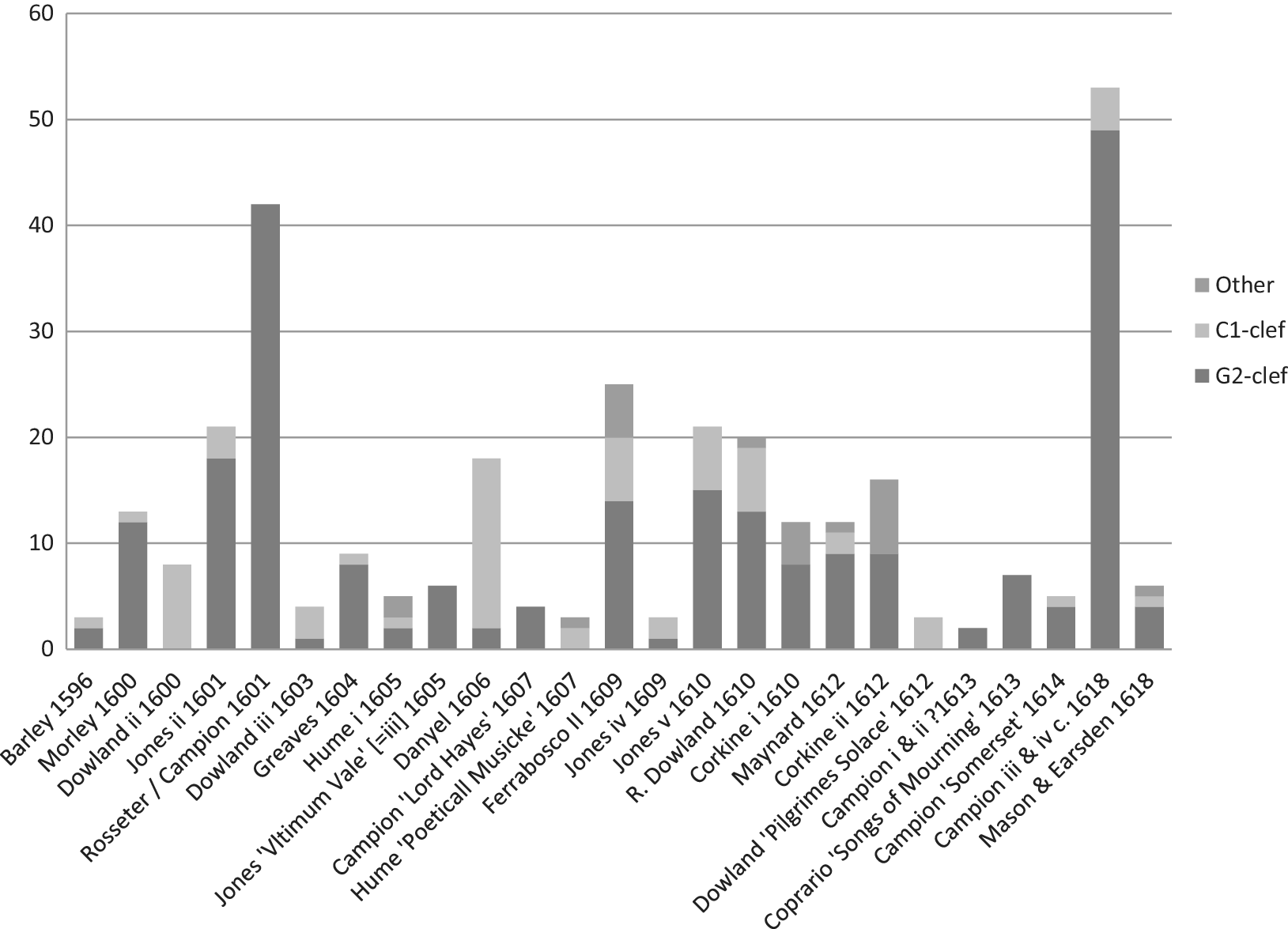

In addition, a musical analysis of the sung melody in the printed lute song collections reveals an overwhelming predominance of high clefs and range.Footnote 74 This can be explained simply in the songs scored for multiple voices via the ‘familiar and infallible’ harmonic rules which governed the process of writing ‘parts in counter-point’, for the presence of lower voices clearly necessitates a high (i.e. ‘treble’) melody.Footnote 75 Yet significantly, of the 322 songs scored for solo voice, only 21 have melodies that exploit lower written ranges and clefs (C3, C4, and F4-clefs, i.e. alto, tenor, and bass-clefs) (see Table 3); in contrast, 232 are in a G2-clef ( =treble-clef), 68 are in a C1-clef ( =soprano-clef) and one is in a C2-clef ( =mezzo-soprano–clef) – that is, a total of 301 ‘high’ solo songs or 93% of the overall total of solo songs (see Figure 1). These solo song melodies generally have a range of around an octave to a minor tenth (see Figure 2), normally somewhere within the compass of d′–g″ (i.e. the lowest and highest notes within a treble stave without using ledger lines); this incidentally matches the typical upper part of the songs set for multiple voices. Indeed, over 75% of the solo songs reach e″ or above. The total number of songs scored for a low solo voice can be extended only marginally beyond 21 songs by including the solo parts in the occasional dialogues and ensemble songs from masques that appear in these collections.Footnote 76

Table 3. Songs for Solo Voice Using Low Clef(s) and Range

Figure 1 Clefs used in the printed lute songs scored for solo voice.

These figures exclude the first song from Campion, The Discription of a Maske […] in honour of the Lord Hayes (which has a tenor part at the back of the book) and the incomplete song (no.14) from Thomas Morley, The First Booke of Ayres (London, 1600). “Other” includes songs in C2, C3, C4 and F4-clefs alongside three songs in the collections of Tobias Hume that use a mix of clefs.

Figure 2 Average written range of sung melody in the printed lute songs for solo voice.

The numbers in the vertical axis relate to the average range in intervals (e.g. 8 = octave; 9 = minor or major 9th, etc.). The mean was calculated correct to the nearest semitone. In the collections with a mode of zero, this indicates that there is no mode (i.e. no clef is more common than any other in the solo songs in this collection). The transposing songs in this collection have been analyzed as written (i.e. the sung melody has not been transposed in the above data); see Table 2.

It is well known that, alongside evidence for boys singing songs to lute or bass viol accompaniment, many references survive in plays, literary sources and letters which describe a woman singing to a lute or (less frequently) bass viol.Footnote 77 Such references can be contextualized within the frequently voiced contemporary opinion that musical skills ranked amongst those accomplishments which were ‘fit for a Lady or Gentlewoman to doe’, and with which she could ‘gette the lykinge of any man’.Footnote 78

Yet evidence for performance of songs or ‘ditties’ by a man with a lute in contemporary written sources appears with similar frequency as texts documenting performance by women.Footnote 79 Indeed, numerous literary references describe a lovesick suitor trying to woo his beloved or ease his suffering from the ‘straunge effects of loue’ by singing with his lute,Footnote 80 whilst other evidence includes references to named male lutenist-singers who were employed at court, such as Guillaume de Vermigny in the early 1560s, described as ‘the singularest player on the lute […] whereunto he sings very well’.Footnote 81 The lute songs themselves add further support to the observation that men and women alike sang these songs since their texts unambiguously express thoughts and desires from both gender perspectives. Yet numerous ‘male’ and ‘female’ songs could be cited which show either no or only negligible differences from one another in terms of clef and registral range – an observation that acquires further significance in the songs scored for solo voice, like the male and female character studies (written in the first person from the perspective of the character) in The XII. Wonders of the World (1612) by John Maynard (bap. 1577–c.1633).Footnote 82 This raises the critical question of the register in which men would have performed these songs: the high register as written using falsetto voice (or loft register), or an octave below sung in chest voice (or modal register).Footnote 83

The tenor voice and the lute song

Judged purely on the music itself, the ‘tenor’ voice – or, more accurately, a man singing the treble melody down an octave in his ‘natural’ modal register in chest voice (i.e. high tenor, tenor, or baritone depending on the song in question) – clearly represents a plausible solution to the registral ‘problem’ of the male voice.Footnote 84 Indeed, most of the songbooks have ranges whose upper notes extend up to g″, sometimes even a″. Important context is provided here by Thomas Morley, who explains in his A Plaine and Easie Introdvction to Practicall Mvsicke (1597/1608) that ‘all songes made by the Musicians, who make songs by discretion’ are set either in the ‘high key’ or ‘lowe key’ and have fixed clefs and ranges. Yet crucially, he then discusses ‘compositions for men onely to sing’ which, he says, ‘neuer passe this compasse’ – accompanied by written-out ranges for four voices, the highest of which only goes up to g′ – and that ‘you must not suffer any part to goe without the compasse of his rules, except one note at the most aboue or below’ (i.e. a′). In addition, the ‘Tenor’ of songs ‘in the high key’ reaches up to a′ whilst the ‘Tenor secundus’ of ‘compositions for men onely’ extends down to B♭ (see Figure 3).Footnote 85 Thus, in short, if the lute songs are sung down an octave by a man in tenor register, they match precisely Morley’s stipulations as outlined here.

Figure 3 Ranges and clefs stipulated for use when composing ‘all songes’ in Thomas Morley, A Plaine And Easie Introdvction To Practicall Mvsicke (London; Humphrey Lownes, 1597), iii, 166 (British Library, Music Collections K.3.m.16.) (© British Library Board, with permission).

A number of hints emerge from the printed song books with tablature that collectively point towards men singing the melody an octave below the written treble pitches. The first clue comes from the handful of songs with bandora accompaniment in A Nevv Booke of Tabliture (1596) by William Barley (?1565–1614).Footnote 86 Surviving evidence suggests that the bandora was particularly linked to the adult male voice in solo songs, which perhaps reflects the instrument’s ‘deepe’- or ‘base’-sounding register.Footnote 87 Indeed, whereas a number of sources describe men playing a bandora and also singing to it, such as on several occasions in Anthony Copley’s Wits Fittes and Fancies (1595), women are connected to the instrument only more passively, like listening to ‘sweet musicke’ on it, and references to a child singing to bandora accompaniment seem to be lacking entirely.Footnote 88 Surviving archival listings add further support to this observation, since these typically indicate male ownership of bandoras.Footnote 89 However, Barley’s sung melodies are all in G2-clefs and C1-clefs with written ranges from d′–f″. Even after the required downwards transposition of the melody by a fourth or fifth to resolve the different written voice and tablature pitches,Footnote 90 the melody is still noticeably higher than Morley’s suggested male vocal ranges – an observation that is all the more notable given Barley’s close professional relationship with Morley, having worked as his assign and printer of several of his music collections.Footnote 91 Sung as written, the tablature also sounds an octave lower than one might expect (i.e. compared to the voice-tablature relationship in songs with lute accompaniment). Sung down an octave, however, the ranges clearly fit Morley’s tenor and bass voice stipulations.

Hints also occur through printed songs that can be connected to known contemporary singers and musicians. Two songs are linked to Robert Hales (fl. 1583–1616), a ‘Groome of her Maiesties Priuie Chamber’ whose singing was admired by a number of contemporaries including Elizabeth I herself.Footnote 92 Both songs exploit high clefs and ranges (if sung as written by an adult male voice): ‘His golden locks’ from John Dowland’s The First Booke of Songes or Ayres (C1-clef, range f#′ to d″), which Hales seems to have performed at the Ascension Day celebrations of Elizabeth I in Westminster in 1590;Footnote 93 and Hales’s own composition ‘O Eyes leaue off your weeping’ in Robert Dowland’s A Mvsicall Banqvet (1610) (G2-clef, written range f′ to f″).Footnote 94 Yet the written vocal tessitura in these songs seems much less fixed once the lute tablature in A Mvsicall Banqvet is carefully examined. Here, the singer’s first note is always given as a cue before each song; this is generally taken from the appropriate note in the lutenist’s first chord, often an octave below the singer’s written pitch (as in Hales’s song). Yet significantly, in two cues in this book, the lutenist has the singer’s starting note twice in his first chord (i.e. at written pitch and an octave below), but he chooses to give the singer the note an octave below as a cue, seemingly hinting at performance by a tenor voice.Footnote 95 To these two songs may be added a third song, whose cue is not in the lutenist’s first chord but which falls easily under his fingers, again suggesting a tenor voice since it would be easy to strike the top string here.Footnote 96 Vocal cues also occur in a related collection of songs with lute tablature, arranged by Sir Edward Filmer (1565/6–1629): French Covrt-Aires, VVith their Ditties Englished (1629).Footnote 97 Like Robert Dowland, Filmer always gives cues an octave below the written pitch of the sung melody. Three of these songs have the starting note twice in the first chord but, like Robert Dowland, Filmer always chooses the lower pitch as a cue (an octave lower than the cantus), again hinting at tenor performance.Footnote 98

Two years after the 1590 Ascension Day celebrations of Elizabeth I, the Queen visited Sudeley Castle whilst she was on progress in Gloucestershire, where entertainments had been organized by Giles Brydges (1548–94), Third Baron Chandos (they were cancelled because of bad weather).Footnote 99 Amongst those due to perform in the Shepherds’ Entertainment seems to have been John Dowland (identified simply as ‘Do.’), who was to accompany the character ‘Cut.’ – perhaps Cutter of Cotsholde or possibly Cutty (i.e. Cuthbert) – in the song ‘Hearbes, wordes, and stones’.Footnote 100 Maybe these are the same as the two musicians who on the previous day would have stood next to Apollo and performed (‘one that sung […] one that plaide’, the latter on ‘lute’) ‘My hart and tongue were twinnes’, a song set by John Dowland in his A Pilgrimes Solace (1612).Footnote 101 Yet if the printed song in any way resembles the one intended for the Shepherds’ Entertainment, it would surely have been sung down an octave if performed by an adult male given the clef and range of its cantus part (G2-clef, range f′ to a″).

Two known contemporary singers are also linked to Campion’s ‘single voyce’ lute songs for the masque of the Earl of Somerset (1614). The first four numbers in this collection are respectively described as having been ‘made and exprest’ and ‘sung’ by ‘Mr. Nicholas Laneir’ (Image 6) and ‘Mr. Iohn Allen’; yet once again, these songs are written in C1 or G2-clefs and have overall ranges of d′ to g″.Footnote 102 Although Lanier’s vocal range cannot be confirmed through external evidence, the likelihood that he sang at tenor range is surely suggested by the description of his co-musician as ‘that most excellent tenor voyce, and exact Singer (her Ma.ties Servant, Mr. Jo. Allin)’ in Ben Jonson’s The Masqve of Qveenes (1609).Footnote 103 Thus, even allowing for the possibility that these songs could have been published in different versions to those heard in the masque, they clearly provide strongly suggestive evidence for a male soloist singing music written in G2 and C1-clefs down an octave in tenor register.Footnote 104

Image 6 Hendrick van Steenwyck the Younger (c.1580–1647), Painting of Nicholas Lanier (1588–1666) holding a lute (1613) (© Private collection, The Weiss Gallery, London, with permission).

A further possible hint that men sang from high clefs down an octave can be found in the few songs that exploit unusually large ranges and a variety of clefs. A pertinent example is ‘Robin is a louely lad’ from George Mason (fl. 1611–18) and John Earsden’s (fl. 1618) ayres performed at the 1618 ‘Kings Entertainment’ organised by Francis Clifford, Fourth Earl of Cumberland (1559–1641) in Brougham Castle, where various characters have solos in different registers (in G2, F4, and C3-clefs) before they join together for a final section and chorus in a G2-clef with a range of g′ to g″ – surely intended to be sung down an octave (or even two) by the singers with F4 and C3-clef solos.Footnote 105 Likewise, in the Ayres (1609) of Alfonso Ferrabosco II (c.1575–1628), two groups of three songs labelled ‘First part’, ‘Second part’, and ‘Third part’ demand an abnormally large overall range of 2.5 octaves from B♭ or c to g″ reading from G2, C1, and C4-clefs;Footnote 106 yet if the songs in G2 and C1-clefs here are sung down an octave, the overall range in each group (c–g′ and B♭–g′ respectively) conforms closely to the tenor ranges outlined by Morley.Footnote 107

Three songs using large ranges and different clefs by Tobias Hume (c.1569–1645) – two from The First Part of Ayres (1605) and one from Captaine Hvmes Poeticall Musicke (1607) – also deserve attention here, since they are closely related in style to the repertory under discussion even though they are, strictly speaking, not lute ayres.Footnote 108 Unlike the previous examples, the clefs alternate midway through both ‘The Souldiers Song’ (variously G2, C1, C2, and C3-clefs, with range g–g″ and tablature for tenor viol) and ‘The Hunting Song to be sung to the Bass-Viol’ (variously G2 and C2-clefs, with range g–a″ and sporadic tablature for bass viol).Footnote 109 Both songs were presumably meant to be sung in their entirety down an octave if performed by a man, since octave downwards transposition of only the passages in G2 and C1-clefs would create odd registral breaks with the passages in C2 and C3-clefs that are surely not intended.Footnote 110 When the whole melody is transposed down an octave, it not only brings the songs in line with Morley’s male voice stipulations, but it also resolves the otherwise peculiar incongruity between music (i.e. treble register) and text (i.e. from the soldier’s or huntsman’s perspective).Footnote 111 Indeed, it seems unlikely that a man singing the songs as written (in falsetto, reaching up to g″) could really convey with any gravitas for contemporaries the ‘wel gotten skars’ of battle ,‘the brauery of glittring shields’, and the ‘shoutes and soundes of hornes and houndes’ mentioned in the songs, particularly given Hume’s first-hand experience as a soldier.Footnote 112

The third song, ‘Alas poore men’ (variously G2, C1, C3, C4, and also F4-clefs, with range F–f″ and bass viol tablature), is slightly more problematic, since the F4-clef section would be too low if the whole song is transposed down an octave. Footnote 113 As it stands, its three-octave range exceeds by some way any other contemporary English music for solo voice, even outstretching works written several decades after 1650 for the bass John Gostling (1644–1733), who was famed for his low notes and had a range of at least two octaves (D–d′).Footnote 114 Likewise, other songs with large ranges from elsewhere in Europe c.1600 – notably in Italy by composers such as Ottavio Valera (early seventeenth century) and Giulio Caccini (1551–1618) – are markedly different in character and style from Hume’s song, instead showcasing vocal virtuosity and utilizing many fast runs.Footnote 115 Thus, if ‘Alas poore men’ really was intended for performance as written by one singer,Footnote 116 how was he supposed to convey an appropriately sombre mood in its execution, as befitting the song’s accompanying performance instructions which clearly convey its serious nature as an ‘Imitation of Church Musicke’?Footnote 117 Likewise, given that English theoretical writings on music c.1600 considered the ‘naturall compasse of mans voice’ to be between ‘an Interuall by a Fifteenth’ and ‘xx. notes and no more’, how could printing the song have represented a sensible marketing decision, especially from a printer like John Windet (fl. 1584–1611) who had an established reputation?Footnote 118 Perhaps the F4-clef section was to be sung at pitch whilst the G2 and C-clef sections were to be transposed (as in the previous examples); in any case, the song clearly represents an unusual and exceptional conundrum.

Within the context of all the hints described above in the songbooks for men singing from high clefs an octave below, Campion’s observation in his Tvvo Bookes of Ayres (?1613) that ‘the Treble tunes, which are with us commonly called Ayres, are but Tenors mounted eight Notes higher’ surely acquires significance.Footnote 119 More crucially, in his singing instruction manual in The Schoole Of Mvsicke (1603), Thomas Robinson (c.1560–1610) – after discussing the ‘Gam-vt’ and its relationship to tablature – explicitly incorporates singing ‘eight vnder’ into his definition of singing ‘with the Lute in the vnison’:

‘Now you haue gotten the way to tune your voice, (note for note) with the Lute in the vnison, (that is: all in one tune or sound, or eight vnder) then you may rule your voice to the Viol also … ’Footnote 120

Francis Bacon (1561–1626) likewise notes in his Sylva Sylvarvm (1627) that the ‘Diapason or Eight in Musicke […] is in effect an Vnison’, as in bass courses on lutes tuned ‘one an Eight aboue another; Which make but as one Sound’.Footnote 121 Additional related evidence further substantiates contemporary performance of lute song melodies an octave below the written pitches by a tenor or baritone voice.Footnote 122 Yet what about a man singing the songs at the written pitch using falsetto voice (or loft register) and only occasional modal register for lower notes? (Image 7).

Image 7 Anonymous (c.1615), Wall painting of lute player, originally in a bedroom in the west wing of The Swan Inn, No.1 London End, Beaconsfield, now in Aylesbury Museum (© Bucks Free Press, with permission).

The male falsetto voice and the lute song

According to Michael Praetorius (1571–1621), the ‘falsetista’ of Continental polychoral music had the same range as the ‘Evnuchus’ and ‘Discantista’, that is from b or c′ to somewhere between e″ and a″.Footnote 123 Praetorius therefore primarily considered the falsetto voice to be a soprano voice (not alto, as it is typically used today). This ‘male soprano’ range is clearly sufficient to execute the cantus parts of lute songs as written, assuming the full upper range up to a″ is usable (which, incidentally, is usually not the case for modern countertenors or falsettists apart from specialist sopranists).Footnote 124 The word ‘falsetto’, however, appears to have been virtually unknown in England: it only seems to occur in the 1598 and 1611 Italian-English dictionaries of John Florio (1553–1625), who defines it as ‘a false treble or counter-tenor in musicke’.Footnote 125 Florio’s phrase ‘false treble’ also seems to be absent from other English sources until later on.Footnote 126 The Italianate context of this source is thus noteworthy, since falsetto singing seems to have been known in Italy, as famously described by the English traveller Thomas Coryat (c.1577–1617) on his travels to Venice in 1608.Footnote 127

Similarly, the modern association of male falsetto singing with the word ‘countertenor’ (which Florio could appear to substantiate) seems not to reflect general usage in England at this time, which may indicate Florio’s difficulty in finding a clear definition for ‘falsetto’.Footnote 128 The word ‘countertenor’ normally occurs alongside various combinations of ‘treble’, ‘mean’, ‘tenor’, and ‘bass’ in contexts ranging from choirs to bell sizes and forest birds;Footnote 129 its primary function as a part name is underlined through conflation with terms like ‘contra-tenor’, ‘counterbase’, and ‘counterpoynt’.Footnote 130 Only one source – Campion’s description of the 1613 entertainment at Reading for Anne of Denmark (1574–1619) given by Lord Knowles – apparently describes a ‘counter-tenor voice’ in music that may have resembled the lute song.Footnote 131 Its accompaniment by ‘two vnusuall instruments’, however, may suggest a specific intended effect here; perhaps this ‘counter-tenor voice’ sang a harmony part (like the altus) instead of the melody.Footnote 132 More significantly, the only example of a contratenor in Campion’s lute song books is actually written in a C3-clef with the range d to f′.Footnote 133 This range is not only virtually identical to other tenor parts in Campion’s songs,Footnote 134 but it also matches exactly two of the tenor ranges stipulated by Morley in A Plaine and Easie Introdvction: the ‘Tenor’ in the ‘low key’ and the ‘Tenor primus’ in the ‘compositions for men onely to sing’ (both in C4-clef, range d–f′).Footnote 135 The ‘counter-tenor voice’ Campion describes in the 1613 entertainment was thus probably a high tenor, not a falsettist.Footnote 136 Further support for this reading may be found in Le Roy’s description of lute strings (‘the high Tenour, called in Latine Contratenor […] is nexte to the highest, or Treble’) and Dowland’s translation of Micrologvs (‘the high Tenor, is the vppermost part, saue one of a Song’), amongst others.Footnote 137 Indeed, this meaning of ‘countertenor’ most likely derives from the term’s origins in late medieval music, where the ‘contratenor’ originally occupied a similar range to the ‘tenor’ and was later subdivided into ‘contratenor altus’ and ‘contratenor bassus’ respectively.Footnote 138

Lastly, it is important briefly to address the ‘Evnuchus’ mentioned by Praetorius. Although known to English readers through literary texts, the eunuch represented something theoretical, not real, in English society, as exemplified by those sources that refer to the Biblical passage in Acts 8 where Philip the Evangelist met the Ethiopian eunuch;Footnote 139 indeed, actual English contact with eunuchs was seemingly had solely by English ambassadors abroad.Footnote 140 Only a tiny handful of English sources mention a eunuch singing to a lute, a character that is primarily used to conjure up exotic authenticity in ancient and foreign settings.Footnote 141 Unlike in Continental princely chapels,Footnote 142 eunuchs seem not to have been employed in English royal or ecclesiastical choirs, nor are they apparently mentioned in descriptions of actual English music-making – a fact exemplified by the letters of Richard Champernoun of Modbury (c.1558–1622) to Sir Robert Cecil (1563–1612) in 1595, in which he fiercely denied ‘an ydle & vntrew report of mee as a gelder of boyes for preserving theyr voyces’, noting that such action would be ‘agaynst reason, & the law’.Footnote 143 More importantly, eunuchs were generally believed to represent an odd middle gender (‘lesse then a man, & halfe a woman’),Footnote 144 and were seen as ‘vnperfect’, ‘effeminate’, and ‘womanish’.Footnote 145 These negative assessments link to more general contemporary suspicion aroused by effeminate men, who were considered to ‘have degenerated into women’ and thus to have transformed ‘from the more perfect to the imperfect’;Footnote 146 indeed, he who ‘hath the voyce lyke a woman, is estemed of the wise to haue litle vnderstanding or knowledge’ – something that the aspiring courtly amateur male musician could hardly think it worth emulating.Footnote 147

On the face of it, therefore, evidence for the falsetto voice in the lute song appears to be absent. Nevertheless, the possibility that contemporary Englishmen used different terminology to ours to mean falsetto singing remains open. Indeed, the vocabulary used c.1600 to describe spoken and sung voices reveals slight differences between Elizabethan and modern English, and careful analysis is required to unravel the subtle nuances and meanings intended. For example, whether spoken, sung, female, or male, a ‘low’ voice often simply meant one that was quiet, weak or submissive (rather than indicating pitch), as in Thomas Ravenscroft’s (c.1588–1635) prefatory singing directions in The Whole Booke Of Psalmes (1633), which contrasts ‘low’ with ‘loude’.Footnote 148 Likewise, a ‘high’ voice frequently indicated excitement, emotion, or a loud volume rather than exclusively describing pitch per se; this is exemplified by Stephen Batman’s (d. 1584) observation that the ‘perfect voyce’ in music should (amongst other things) be ‘high to bee well heard’.Footnote 149 This conflation of ‘high’ and ‘loud’ versus ‘low’ and ‘quiet’ is frequently seen in contemporary descriptions of (loud) ‘treble’ versus (soft) ‘tenor’ and ‘bass’ voices,Footnote 150 and it can be traced back through several previous centuries in literary, musical, and theoretical sources from across Europe.Footnote 151 Thus, it seems that ‘high’ and ‘low’ often relate only partially or indirectly to pitch except where musical ‘notes’ or ‘sounds’ are explicitly described, but even here, the terms must be understood in a relative sense and therefore fail to provide clear evidence for falsetto singing.Footnote 152 Other words used to describe voices include ‘small’ and ‘litle’ – generally for women, children and eunuchs – or ‘great’ and ‘deepe’ – generally for men. This distinction occurs frequently and was linked to understanding of biological differences between ages and genders;Footnote 153 indeed, ‘a great voyce in a woman’ was considered to be ‘an euill sygne’, whereas men who had a ‘small voyce’ were thought to be weak.Footnote 154

Occasionally, specific musical terminology is also used. Several texts mention a man’s ‘treble voyce’, which could initially seem to indicate falsetto singing, although it should be noted that none of these references occur in relation to lute accompaniment.Footnote 155 A number of these describe the typical ‘ballad-monger’ or ‘common Fidler’ who, amongst other things, ‘can Match his Treble to the Uioll’.Footnote 156 However, these are illiterate singer-sellers who are usually portrayed in unambiguously unflattering terms – for example, as so impoverished that ‘his totall meanes amounts but to fiue markes, which he hath miseraby [sic] beene scraping all his life-time’ and whose best source of income is ‘Drunkards, and such as are lasciuiously inclin’d’ – a somewhat different context, audience, and performer from those of the printed lute song collections.Footnote 157 Furthermore, the collective references that describe a man’s ‘treble’ voice are not only tiny in number but they also seem to be predominantly metaphorical (meaning ‘at the top of his range’) rather than indicating literal pitches in a G2-clef.Footnote 158 The same is true of references to a man singing or exclaiming ‘a note aboue Ela’ (‘Ela’ was the highest note in the Guidonian system, i.e. e″), where a literal reading is undermined by the existence of similar wording in relation to women’s voices.Footnote 159

Discussions of the voice in contemporary anatomical and rhetorical works and almanacs provide further context here. In his Mikrokosmographia (1615), for example, the royal physician Helkiah Crooke (1576–1635) noted that a man might ‘vary’ his spoken voice ‘high, low, or in a middle key, or as we say Treble, Base or Tenor’,Footnote 160 whilst others like Robert Robinson (fl. 1617) and Richard Mulcaster (?1530–1611) used more generic terminology to describe man’s spoken range (from ‘shrill and lowd’ to ‘base and deep’).Footnote 161 Several writers noted that the ‘meane’ was the optimal spoken voice for a man, since a ‘meane voyce in sounde and in greatnes, declareth the man to bee wyse, circumspecte, iuste, and trew’.Footnote 162 Clearly, in such passages, ‘meane’ does not indicate the musical pitch associated with the ‘meane’ sung voice of a boy; rather, it relates here to a midrange adult male voice, and such usage was not confined exclusively to ‘scientific’ texts.Footnote 163 These writings about a man’s spoken voice in turn contextualize descriptions of a man’s singing voice that imply a similarly large range, like that of Philemon Holland (1552–1637), who noted that ‘Musicians are woont to guide and rule the voice gently by little and little up and downe, betweene base to treble, according to everie note as they would themselves, teaching their scholars thereby to have a tunable voice’.Footnote 164 Furthermore, the general preference for a ‘meane’ (i.e. midrange) adult male spoken voice convincingly explains why some texts that discuss man’s singing actually seem to conflate ‘a Meane, or Tenor’.Footnote 165 In any case, the rarity of references to a man’s ‘treble’ voice can be set alongside equally unusual descriptions of female voices that use words such as ‘alt’, ‘tenour’, and even ‘bace’.Footnote 166

Finally, the verb ‘faine’ or ‘feign’ (and its related adjectives) has sometimes been assumed to indicate the ‘falsetto’ voice in scholarship to date.Footnote 167 The musical use of this word seems to have been linked closely to its more typical nonmusical definitions: ‘to counterfeit’, ‘to inuent a lie’, ‘to falsifie’, etc., much like the modern ‘feign’. For example, the lexicographers Richard Huloet (fl. 1552) and Thomas Cooper (?1517–94) translate the Latin verb ‘incino, incinere’ respectively as ‘Singe a tryple, properly to fayne a small breast’ and ‘To sing: to feyne a small voyce: to sowne pleasantlye and with melodie’, thus equating singing a treble part with imitating or pretending to have a high voice.Footnote 168

A famous musical use of ‘faine’ that might perhaps indicate falsetto singing (possibly for a specific effect) occurs in Thomas Campion’s description of the 1613 entertainment cited above, where ‘the Robin-hood-men faine two Trebles’ in a five-voice song.Footnote 169 Yet the idea that this word generally meant falsetto singing at this time is questionable. John Florio, for example, does not link ‘faine’ to ‘falsetto’ (or ‘false treble’), even though he uses this word in another musical context, in his entry for ‘Croma’: ‘ … pleasant and delightsome musike with descant, faining or quauering’, a description which closely resembles Philemon Holland’s definition of ‘Chromaticke Musicke’.Footnote 170 Other sources also suggest a link between ‘faine’ and ornamentation, such as Nicholas Breton’s The Court and Country (1618), which twice contrasts ‘faine’ with ‘sing plaine’.Footnote 171

The word ‘faine’ elsewhere seems to relate to a soft volume in musical contexts. A pertinent example occurs in Cooper’s translation of a Latin quotation of Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (c.35–100 AD) (‘elisa voce canere, vel loqui’): ‘To feygne in singing: to speake in a small feygning voyce: also to speake or singe as one coulde heardely vtter his voyce’.Footnote 172 Other musical references appear to conflate ‘faine’ with ‘faint’ or ‘faintly’,Footnote 173 recalling in turn the frequently seen link between ‘tenor’ or ‘bass’ singing and a ‘soft’ delivery, as in contemporary translations of the Latin ‘succino, succinere’ (rendered variously as ‘to fain in singing’ and ‘To make a soft noyse: to sing a base or tenor’, etc.).Footnote 174 Indeed, in his 1593 translation of a French description of a nightingale’s singing, in which the bird traverses different polyphonic voice parts (from treble to bass), John Eliot renders the verb ‘contrefaire’ in four ways – ‘sings’, ‘counterfeiteth’, ‘quauereth’ and ‘faineth’ – significantly, pairing ‘faineth’ with ‘the base’.Footnote 175

Other examples of ‘faine’ in musical contexts seem to indicate a manner of delivery, such as the use of cunning or pretence, as in A Midsommer nights dreame (1600) by William Shakespeare (1564–1616), where Egeus complains that Duke Lysander has stolen his daughter’s heart after having (amongst other things) ‘by moone-light, at her windowe sung, / With faining voice, verses of faining loue’.Footnote 176 This may link to nonmusical definitions such as Abraham Fraunce’s (1558–92) explanation of the literary device prosopopoeia – the ‘fayning of any person, when in our speach we represent the person of anie, and make it speake as though he were there present’Footnote 177 – in turn perhaps explaining why some sources appear to distinguish ‘faine’ from ‘sing’.Footnote 178

Whatever ‘faine’ therefore means in any given example from a musical context, it clearly represents problematic evidence for the falsetto voice in the lute song repertory. Moreover, it would appear that it was not always used exclusively to describe male voices, since at least one contemporary literary text – The second Tome of the Palace of Pleasure (1567) by William Painter (?1540–94) – describes ‘three Amorous Gentlewomen’ who each had ‘a heauenlie voice to faine and sing’.Footnote 179 Similarly, almost none of the numerous contemporary English literary references that describe a man singing to a lute use the word ‘faine’, and those that do seem to fall outside the immediate period in which the lute song collections were printed (1597–1622; see Appendix 2). Instead, most sources simply use ‘sing’ or sometimes ‘warble’, or more rarely words like ‘accord’, ‘sought out’, and ‘sound’.Footnote 180 The tiny handful of references which mention a man ‘faining’ to a lute are also primarily translations of foreign texts from countries where falsetto singing may have been more known.Footnote 181

In view of all of the above, it therefore seems likely that lute songs were not intended for a man singing in his falsetto voice. Indeed, this manner of singing can only be justified in the lute song repertory by assuming that words like ‘sing’ and ‘warble’ function as generic umbrella terms for any vocal technique or style of performance imaginable. Contemporaries also seem to have favoured a ‘naturall voyce’,Footnote 182 and even some modern exponents of the falsetto voice do not consider it to be ‘natural’.Footnote 183 Furthermore, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writers clearly distinguished the sound of a ‘mannes voyce’ from a ‘boyes voyce’,Footnote 184 and unambiguous evidence for English men singing in a soprano range to lute accompaniment seems to be similarly absent.

Conclusions

Having analysed the printed lute song collections alongside evidence both for the lute and also singing in late Tudor and early Stuart England, the following conclusions may be drawn. Firstly, it is evident that all of the lute song collections were printed in a format which was supposed to facilitate instant performance, primarily with a mean lute in g′ or bass viol (or both together) and, except in rare cases where the voice has to fit the lute’s differently pitched tablature, without the need for any transposition. Secondly, this repertory was intended for singers of all ages and both genders, with women and children singing the song melodies in the written treble register and men singing them in the octave below (excluding the occasional songs that use low clefs like C4 and F4-clefs, which were clearly intended primarily for a male voice at pitch). It also seems very questionable that this performance solution might have changed simply depending on the amateur or professional background or context of the singer.Footnote 185 Perhaps more importantly, these specific conclusions about the lute song provide further support for the recent research which has challenged the use of falsetto singing in England more generally at this time (particularly within a sacred context). In short, perhaps the lost soundworld of ‘the sweetest Lute, and best composed song’ in England c.1595–1625 is finally emerging with more clarity via a better understanding of the likely voices which would ‘to the lute full many a dittie sing’.Footnote 186

Acknowledgements

A version of this paper was presented at the Medieval and Renaissance Music Conference in Basel, July 2019. I am indebted to John Bryan, Katherine Butler, Christopher Page, John Potter, Anthony Rooley, Richard Wistreich and Crawford Young for their advice on early versions of this article. I am also grateful to Michael Fleming for providing several references in Appendix 1a, and to Christopher Goodwin, Elisabeth Leedham-Green, John Milsom, Robert Thompson and David van Edwards for their assistance with various other queries.

APPENDIX 1a

References to Lutes in Noble and Gentry Inventories, Wills, & Other Documents (1585–1635).

Note. This table aims to give a representative overview (and as comprehensive as possible) of lute ownership across the period in question; it excludes references to lute strings and/or lute books unless these are explicitly listed with a lute, and it also omits the other instruments that are sometimes listed alongside these lutes. The repository and shelf mark abbreviations follow the format used in ‘Records of Early English Drama’.

Source. In addition to several references generously supplied by Michael Fleming, this list was compiled with the aid of staff in the Hull History Centre, Norwich Records Office, Durham Record Office / Durham University Library, Oxfordshire History Centre, Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service, and Dulwich College. In addition, the following sources were used: the multivolume collections of ‘Records of Early English Drama’ (REED, 1979–), http://reed.utoronto.ca; ‘The Henslowe–Allen Digitisation Project’, https://henslowe-alleyn.org.uk; Lionel Cust, ‘The Lumley Inventories’, Walpole Society, 6 (1918), 15-35; Michael Fleming, ‘Some Points Arising from a Survey of Wills and Inventories’, The Galpin Society Journal, 53 (2000), 301–11; Michael Fleming, ‘Unpacking the ‘Chest of Viols”, Chelys, 28 (2000), 3–19; Michael Gale, ‘Learning the Lute in Early Modern England c.1550–c.1640’ (Ph.D. diss., University of Southampton, 2014); Historical Manuscripts Commission (HMC), The Manuscripts of his Grace the Duke of Rutland GCB Preserved at Belvoir Castle, 4 vols (London: HMSO, 1888–1905); Peter Holman, Four and Twenty Fiddlers: The Violin at the English Court 1540–1690 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993); Lynn Mary Hulse, ‘The Musical Patronage of the English Aristocracy, c.1590–1640’ (Ph.D. diss., King’s College, University of London, 1992); Elisabeth Leedham-Green, Books in Cambridge Inventories; Teresa Ann Murray, ‘Thomas Morley and the Business of Music in Elizabethan England’ (Ph.D. diss., University of Birmingham, 2010); Tessa Murray, Thomas Morley: Elizabethan Music Publisher; David C. Price, Patrons and Musicians of the English Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

APPENDIX 1b

REFERENCES to LUTES in COURT RECORDS 1585–1635.

Note. This table aims to give a representative overview of references to lutes in court archives. It generally excludes references to lute strings and/or lute books unless these provide more information about the lute’s size, number, or purpose (references marked *) or unless these are explicitly listed with a lute.

Source. The information is taken from the nine-volume collection by Andrew Ashbee, ed., Records of English Court Music; the relevant volume and page number are given in brackets in the source details column.

APPENDIX 2

Descriptions of a Man Singing to a Lute in English Printed Literary Sources (1595–1625)

The following list closely follows the date range of the printed lute song collections under consideration. The literary references from this relatively narrow spectrum may be seen as representative in type and in the vocabulary used of earlier and later sources describing a male singer with lute across the period 1550–1650. This table excludes: a) references to male singing and lute with other instruments (i.e. ensemble performance); b) descriptions of a man playing a lute that do not mention him singing to it; c) references that mention a eunuch who sings to the lute; and d) texts that relate generically to singing with lute that do not specify the singer’s gender or where this is unclear.

In the book titles and subheadings, words in capital letters have been rendered with small letters, but capitals have been retained at the start of words as they appear in the original. All letters have been kept as they appear in the original (including ‘u’ and ‘v’). Additions or omissions are indicated with square brackets (i.e. []).