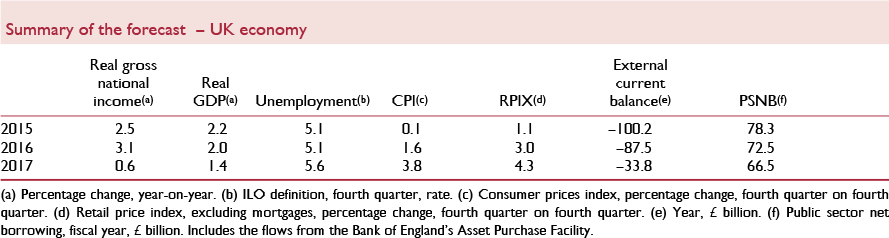

The ONS’ preliminary estimate for third quarter GDP growth of 0.5 per cent was more robust than we expected back in August. However, the outlook remains one of a slowing economy, confronted with significant risks. We have revised up our GDP forecasts from August to 2 per cent in 2016, slowing to 1.4 per cent in 2017. Rather than a significant change to our view of the future, this is largely due to revisions to historic data. Our projections for quarter-on-quarter GDP growth over the next two years are broadly in line with the figures published three months ago.

There are signs of substantial impending inflationary pressure, especially when one looks at the price indices that tend to lead consumer prices. Much of this is driven by the dramatic fall in sterling, which has been one of the most striking features of the post-referendum data. In the past three months, sterling has hit a 31-year low against the dollar and a 5-year low against the euro. As this depreciation is passed through to consumer prices, we expect CPI inflation to accelerate rapidly, reaching around 4 per cent in late 2017 and only returning to the Bank of England's 2 per cent target in 2020.

This outlook of weak demand and above target inflation presents a trade-off for monetary policy. We expect the Bank of England to look through the near-term inflation increase and hold the stance of policy constant until the second half of 2019. After this point, Bank Rate is expected to tighten gradually, reaching just 1¾ per cent by the end of our forecast horizon. Our analysis suggests that the policy measures announced by the Monetary Policy Committee in August could add as much as 2/3 per cent to the level of GDP. We also find that they will have a notable impact on the public finances, improving them by around £4 billion per annum over the next five years.

The slowdown in activity coupled with uncertainty could lead to a delay in firms’ hiring plans which we expect to be only partially offset by weak real wage growth. We project unemployment to peak at 5.6 per cent in 2017, before gradually returning to its long-run level. The corollary of this is that labour productivity growth remains muted.

The trade balance is expected to benefit from the depreciation of sterling with both increased export volumes and a reduction in import volumes. Alongside an improvement in the primary income balance, the current account deficit is predicted to narrow sharply from 4.5 per cent of GDP this year to 1.7 per cent in the next and reaches surplus in 2019.