1 Introduction

It is a longstanding question in lexical semantics which normally transitive verbs in English can omit their objects to describe an event with an unexpressed theme, which cannot, and why.Footnote 2 Even near-synonyms differ in how natural they sound with their objects omitted (1) (Fillmore Reference Fillmore1986; Rice Reference Rice1988; Mittwoch Reference Mittwoch, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005; Gillon Reference Gillon2012), making it difficult to explain omission in terms of meaning, and leading some researchers to characterize this phenomenon as partly or fully arbitrary (Fillmore Reference Fillmore1986; Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff2002; Ruppenhofer Reference Ruppenhofer2004; Gillon Reference Gillon2012; Ruppenhofer & Michaelis Reference Ruppenhofer, Michaelis, Bourns and Myers2014).

(1)

(a) I ate__vs. ?I devoured__

(b) I drank__vs. ?I guzzled__

(c) I wrote__vs. ?I penned__

(d) I raked__vs. ?I bagged__

This article focuses mainly on cases where the omitted object is said not to require a discourse antecedent, rather than anaphoric cases such as I noticed (Allerton Reference Allerton1975; Fillmore Reference Fillmore1986; Condoravdi & Gawron Reference Condoravdi, Gawron, Kanazawa, Piñón and Swart1996; Olsen & Resnik Reference Olsen and Resnik1997); but, since this distinction becomes fuzzy in practice, the article does not attempt to separate so-called indefinite/existential from definite/anaphoric object omission in corpus data.

Joining those who strive for a predictive explanation of which verbs allow object omission to what extent and why (Resnik Reference Resnik1993, Reference Resnik1996; Cote Reference Cote1996; Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Rappaport Hovav, Levin, Butt and Geuder1998; Velasco & Muñoz Reference Velasco and Muñoz2002; Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Rappaport Hovav, Levin, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005; Iten et al. Reference Iten, Junker, Pyke, Stainton, Wearing, Junker, McGinnis and Roberge2005; Martí Reference Martí2015), this article aims to disentangle three factors suggested to facilitate object omission (section 2):

• selection: how much statistical information a verb provides about the taxonomic nature of its object (Resnik Reference Resnik1993, Reference Resnik1996).

• frequency: the per-million-word frequency of a verb in a corpus (Goldberg Reference Goldberg, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005).

• routine: the degree to which a verb describes a conventional action within a community (Lambrecht & Lemoine Reference Lambrecht, Lemoine, Fried and Boas2005; Martí Reference Martí2010, Reference Martí2015; Levin & Rapaport Hovav Reference Levin, Hovav, Pensalfini, Turpin and Guillemin2014).

Ultimately, the article draws on data from corpora and experiments to argue that routine – distinguished from selection and frequency – is an important factor in facilitating object omission. The contrasts in (1) are argued to arise when one half of the minimal pair is more strongly associated with a routine than the other.

Selection and frequency are easily measured, but a verb's association with a routine is inherently an elusive social/mental concept, likely to correlate with both selection and frequency in corpora, not strictly entailed, and thus very difficult to measure directly. To make headway, the article leverages the assumption that a verb's association with a routine is a gradient notion which varies across social communities (Eckert & McConell-Ginet Reference Eckert and McConell-Ginet1992). Even if we cannot say absolutely whether a verb such as lift describes a routine, we may establish that it is relatively more strongly associated with a routine in one community (strength-training enthusiasts) than another (laypeople). Comparing across communities, we can ask: does lift omit its object more often in the writings of strength-training enthusiasts? If lift omits its object more often in a given community's writings, can it be shown that lift describes an action that is more strongly associated with a routine for that community?

Section 3 presents corpus studies of Reddit, a web forum organized into more or less specialized subcommunities, where a combination of natural language processing tools and human labor is used to identify object omission at a large scale.Footnote 3 Comparing specialty communities (such as r/strengthtraining) to generalist ones (such as r/AskReddit), verbs are identified which differ statistically significantly in the proportion of object-omitting tokens between a specialty community versus the generalist one. The result is a dataset of 134 of verbs (including lift) used significantly more often without an object in various specialty communities. These data allow the selection, frequency and (arguably) routineness of the same verb to be compared across communities, offering evidence consistent with the claim that verbs more readily omit their objects when they describe routines.

Crossing routine with selection and then with frequency in controlled experiments, and again leveraging the fact that certain actions are more or less routine for different people, section 4 offers further evidence that routine itself facilitates object omission. Section 5 sketches a semantics of object-omitting verbs taken from prior literature, but supported with new evidence: object-omitting tokens are analyzed as intransitive aspectual activities describing the routine actions of an agent. Section 6 situates the article against previous work, acknowledging that there are many factors contributing to this complex phenomenon, but arguing that the current proposal synthesizes earlier insights. In sum (section 7), this article offers data to advance the decades-old debate on object omission; tackles the challenge of empirically measuring routine; and aims to illuminate verbs as social artifacts, shaped by the practices of the people who use them.

2 Selection, frequency, routine

2.1 Selection

In a rigorous corpus study which inspires this one, Resnik (Reference Resnik1993, Reference Resnik1996) shows that object omission is facilitated for verbs providing more statistical information about the nature of their object, using the WordNet taxonomy of Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Fellbaum, Kegl and Miller1988). Eat ‘selects’ objects that refer to food, explaining why eat a dumpling is well-attested while eat a thunderstorm is nonsensical. Resnik frames selection in terms of information theory: how much information does the verb provide about the taxonomy of its object? When trying to predict the taxonomic WordNet class of a random object of a random verb, how much uncertainty is reduced by knowing the particular verb?

Perhaps overall very few objects of verbs in a corpus are classified as food in WordNet, so without knowing the verb, the probability of its object referring to a food is low. But when the verb is known to be eat, the probability of its object referring to food is much higher: meaning, statistically, that eat ‘selects’ food to a degree which can be measured mathematically (2) by the change in probability distributions over taxonomic classes of objects (relative entropy) before and after knowing the identity of the verb.

(2) selectional strength S of a verb v is defined as (Resnik Reference Resnik1993, Reference Resnik1996):

$$\eqalign{&S( v ) = \sum _cP( {c\vert v} ) \log \displaystyle{{P( {c\vert v} ) } \over {P( c )}} \cr&{\rm where \ v = verb,\ c = WordNet\ class}$$

$$\eqalign{&S( v ) = \sum _cP( {c\vert v} ) \log \displaystyle{{P( {c\vert v} ) } \over {P( c )}} \cr&{\rm where \ v = verb,\ c = WordNet\ class}$$

Using this definition, eat strongly selects food objects; enjoy has much weaker selection because it appears with objects from many different taxonomic classes.

Resnik shows in a study of 34 frequent verbs (binary-classified into those allowing and disallowing omission) that those allowing object omission tend to have higher selectional strength than those resisting it, and that the more strongly selective verbs also omit their objects proportionally more often.

Resnik does not claim that selection itself drives object omission, but sees selection as a way of quantifying deeper causes posited elsewhere. It is often claimed that a verb's object can only be omitted if the object's identity can be ‘recovered’ (an idea which dates back to Jespersen Reference Jespersen1927: volume II;Footnote 4 Lehrer Reference Lambrecht, Lemoine, Fried and Boas1970; Rice Reference Rice1988; Cote Reference Cote1996). Resnik's finding – that verbs facilitate omission when they provide more selectional information to recover the omitted object – substantiates that claim. Moreover, Hopper & Thompson (Reference Hopper and Thompson1980) group together morphosyntactic and semantic features that they associate with high and low ‘transitivity’, viewed as a gradient property of clauses. For them, the most ‘transitive’ clauses involve objects which are informationally distinct from the verb, while less-transitive clauses involve informationally unsurprising objects. Resnik builds on that observation by showing that object omission, associated with lower transitivity, is favored for objects that are easily inferred.

2.2 Frequency

The frequency of a verb, of course, is the number of times that verb occurs (per million words) in a lemmatized corpus. Goldberg (Reference Goldberg, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005) notes that in minimal pairs such as (1) (eat versus devour), the member of the pair that allows omission is the more frequent one. Following Fellbaum & Kegl (Reference Fellbaum, Kegl, deJong and No1989), she also observes that generic and habitual sentences (Carlson Reference Carlson and Binnick2012) facilitate object omission more than episodic sentences: that dog bites is said to sound more natural than that dog bit yesterday (the ‘characteristic property’ verb alternation of Levin (Reference Levin1993); cf. the idea from Hopper & Thompson (Reference Hopper and Thompson1980) that the most prototypically ‘transitive’ sentences describe particular episodes).Footnote 5

Extrapolating from Goldberg's brief remarks, the suggestion is that if a verb appears frequently in generic or habitual contexts, it is likely to omit its object in those contexts, a pattern which would diachronically generalize to episodic contexts as well.Footnote 6 A verb's frequency, both in generic/habitual contexts and overall, is predicted to positively correlate with object omission.

Contrary to Goldberg's prediction, Ruppenhofer (Reference Ruppenhofer2004: chapter 4) studies 34 verbs, binary-classified into those said to allow or disallow object omission, and finds no association with their frequency in corpora. He concludes that object omission is idiosyncratic.

This disagreement between Goldberg and Ruppenhofer evokes a larger theme in the study of object omission: that relative quantitative claims can succeed where absolute quantitative claims may fail. Goldberg compares across minimal pairs to argue that the member allowing omission tends to be the relatively more frequent one; Ruppenhofer finds that omission does not depend on a verb's absolute frequency. Resnik compares across verbs judged to allow versus disallow omission, finding that those allowing omission tend to have relatively higher selection than those disallowing it; but notes that there is no absolute threshold distinguishing these two types of verbs. This article, too, ultimately presents relative but not absolute quantitative findings.

2.3 Routine

A routine is a series of actions that are well-known and conventional within a community. Routines are rooted in the work of Schank & Abelson (Reference Schank and Abelson1977) and Fillmore (Reference Fillmore1976), who argue that language understanding requires rich background knowledge (called scripts, frames, or schemas) about typical real-life situations. To understand a discourse about a restaurant, one must be familiar with the purposes (dining, commerce), events (ordering, eating, paying), and roles (servers, cooks, diners) typical of restaurants.

A routine is a script for a series of goal-directed actions of an agent that are conventional within a community. Even among verbs describing similar events, some are more strongly associated with a routine than others; exercise evokes routines such as going outdoors or to a gym, wearing workout clothes, and moving around in various ways for a sustained period in order to improve one's health and mood (Levin & Rapaport Hovav Reference Levin, Hovav, Pensalfini, Turpin and Guillemin2014); while jump describes a way of moving one's body but is not associated with a routine for most speakers. (But, to fore-shadow sections 3 and 4, jump may well be associated with a routine for enthusiasts of horseback riding or ice skating.) Many elements of a verb's associated routine are not entailments, but are understood as typical of the events described by that verb.

Transitive verbs describing routines have been suggested to facilitate object omission. Lambrecht & Lemoine (Reference Lambrecht, Lemoine, Fried and Boas2005) observe that French déguster ‘to taste’ allows object omission in a tasting-room context where tasting wines is conventional. Ruppenhofer & Michaelis (Reference Ruppenhofer and Michaelis2010), noting qualitatively that argument omission varies across genres such as diaries and labelese, suggest that omission is favored for verbs describing ‘canonical’ actions within the genre. Martí (Reference Martí2010, Reference Martí2015) analyzes object omission as a silent version of the incorporation of object nouns into verbs, such as berry-pick, which Mithun (Reference Mithun1984) argues is cross-linguistically only available for verb-object pairs describing a community's ‘institutionalized’, ‘name-worthy’ actions. Levin & Rapaport Hovav (Reference Levin, Hovav, Pensalfini, Turpin and Guillemin2014) invoke routine to explain why clean can omit its object (I cleaned yesterday) even though in other contexts it behaves as a ‘result’ verb entailing a change in its theme argument, which in their view requires the theme to be expressed (Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Rappaport Hovav, Levin, Butt and Geuder1998, Reference Rappaport Hovav, Levin, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005; Rappaport Hovav Reference Rappaport Hovav and Rothstein2008; Levin & Rappaport Hovav Reference Levin, Hovav, Arsenijevic, Gehrke and Marin2011). In an analysis intended to generalize to object-omitting tokens of all verbs that otherwise entail a change in their theme argument, they propose that clean is polysemous between a causative change-of-state requiring an object, and an aspectual activity (dynamic and atelic) describing routine actions of an agent typically leading to such changes of state (vacuuming, sweeping), in which case the object can be omitted. Because changes of state commonly co-occur with the routines that bring them about, clean comes to polysemously describe both of them, and can omit its object when it describes a routine.Footnote 7

The claim that verbs facilitate object omission if they describe routines is therefore an old one, but one so far supported by introspective data and often localized to particular case studies. The goal of this article is to test and defend this claim at a large scale. Facing the challenge of measuring the elusive social/mental concept of routine empirically, this article's strategy is to compare the speech/writings of communities who share different routines.

3 Corpus studies of Reddit

Reddit is a popular web forum where users submit content and discuss it in comment threads, organized into communities (subreddits) of different sizes dedicated to more or less specific interests. These subreddits are also more or less linguistically distinctive (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Hamilton, Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil, Jurafsky and Leskovec2017); extremely large, generalist subreddits such as r/worldnews and r/AskReddit use varied vocabulary (by turn discussing popular culture, current affairs, and personal life), whereas smaller, specialty subreddits such as r/bicycling use distinctive, recurring vocabulary related to their central interest.

After explaining the blend of natural language processing and human judgment used to identify object omission in Reddit (section 3.1), I explore features of verbs which might predict how often they omit their objects in generalist subreddits (section 3.2), but find no clear absolute patterns. Next (section 3.3), I find evidence consistent with the claim that verbs are more strongly associated with routines in the subreddits where they omit their objects significantly more often.

3.1 Corpus construction

This study uses the text of Reddit comments from January 2014, cleaned to remove non-ASCII characters, links, deleted and removed comments, and those written by self-identified bots. A dependency parser (SpaCy; Honnibal & Johnson Reference Honnibal and Johnson2015) was used to probe the argument structure of each token of several hundred normally transitive verb types adapted from Levin (Reference Levin1993).

To find tokens where a transitive verb is used with an object, I relied on SpaCy's ‘dobj’ (direct object) dependency. But while ‘dobj’ identifies the presence of a direct object, there is no equally reliable indicator of the absence of one. Among cases where a transitive verb is used without a ‘dobj’ dependency, only a small percentage truly qualify as object omissions; the rest are false positives – passives (it was seen); the middle voice (it washes well); verbs with propositional or infinitival complements (wrote that …); relative clauses (the sandwich that I ate); prepositional complements (trust in God, hate on them); particle verbs (sign up for a race); incorrect part-of-speech tags (Best Buy), and more. Other false positives arise from the causative-inchoative alternation (Smith Reference Smith, Jazayery, Polomé and Winter1970; Levin Reference Levin1993), where the same verb can either appear with an agent subject and a patient object (the campers burned a fire) or just a patient subject (the fire burned) – in contrast to object omission, where a verb has an agent subject and no object (I ate).

These false positives were addressed using a blend of automated and human methods. First, I automatically excluded all sentences containing passives; all verbs with particles, prepositional phrases, clausal, or adverbial complements as dependents; all verbs inside relative clauses; all verbs used as auxiliaries; and all verbs related to anything else by a conjunction. To avoid biasing the data, these exclusions applied equally to verbs with a ‘dobj’ dependent as well as those without. In an attempt to remove inchoative tokens of causative verbs (the fire burned), I used a semantic role labeling tool (He et al. Reference He, Lee, Lewis and Zettlemoyer2017) available through the AllenNLP tool suite (Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, Grus, Neumann, Tafjord, Dasigi, Liu, Peters, Schmitz and Zettlemoyer2018), excluding tokens with an automatically labeled patient ‘arg1’ but no agent ‘arg0’ – although this tool still lets many inchoative uses slip through undetected.

After all of these automatic exclusions, the result was a fairly accurate set of sentences where transitive verbs were used with direct objects; and a set of sentences with no ‘dobj’ dependency which still contained more false positives than true positives for object omission. I then read all of these sentences and removed all remaining false positives for object omission by hand, to yield a corpus that is both large and trustworthy.

3.2 Object omission in generalist subreddits

As a first look at object omission in the Reddit, I use data from generalist subreddits to test and then reject hypotheses drawn from the work of Resnik (Reference Resnik1993) and Goldberg (Reference Goldberg, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005):

(3) The Absolute Selection → Omission Hypothesis [Resnik (Reference Resnik1993); not empirically supported]: There should be a positive correlation between the strength of a verb's selection for its object and that verb's propensity to omit its object.

(4) The Absolute Frequency → Omission Hypothesis [Goldberg (Reference Goldberg, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005); not empirically supported]: There should be a positive correlation between a verb's frequency and that verb's propensity to omit its object.

For each of the 832 normally transitive verbs studied, the dataset (available at https://osf.io/kxe3u/) records a list and count of all uses of the verb with and without a direct object; the percentage of the time the verb omits its object; the verb's per-million-word frequency; and two different metrics for its selectional strength, which as expected are highly correlated: (i) Resnik's metric ![]() $S( v ) = \sum _cP( {c\vert v} ) \log {{P( {c\vert v} ) } \over {P( c ) }}$, where v = verb, c = WordNet class; and (ii) a ‘simple’ metric from Chambers & Jurafsky (Reference Chambers and Jurafsky2010): of all tokens of the verb with a direct object, the percentage of tokens with the verb's most common lemmatized object which is not a pronoun (undefined, and excluded from all analyses, if there is no most-common non-pronoun object).

$S( v ) = \sum _cP( {c\vert v} ) \log {{P( {c\vert v} ) } \over {P( c ) }}$, where v = verb, c = WordNet class; and (ii) a ‘simple’ metric from Chambers & Jurafsky (Reference Chambers and Jurafsky2010): of all tokens of the verb with a direct object, the percentage of tokens with the verb's most common lemmatized object which is not a pronoun (undefined, and excluded from all analyses, if there is no most-common non-pronoun object).

To test the Absolute Selection → Omission Hypothesis, a linear regression model was used to predict the percentage of the time that a verb omits its object as a function of its selectional strength.Footnote 8 Neither a verb's Resnik selection nor its simple selection has any meaningful effect on the percentage of the time that it omits its object, as reflected by multiple R2 values of less than 0.01 – meaning that the models explain less than 1 percent of the variability across verbs. Contrary to Absolute Selection →Omission Hypothesis, and in contrast to Resnik's findings which used data from 34 verbs, these data offer no convincing evidence that selection facilitates object omission.

As for the Absolute Frequency → Omission Hypothesis, another linear regression was used to predict the percentage of object-omitting tokens of each verb as a function of its per-million-word frequency.Footnote 9 Consistent with Ruppenhofer (Reference Ruppenhofer2004), and contrary to the Absolute Frequency → Omission Hypothesis, there is no relationship between a verb's frequency and the percentage of the time that its object is omitted.Footnote 10

In sum, this section finds no support for the hypotheses (3)–(4). Next, I compare generalist subreddits to specialty subreddits where certain verbs are arguably comparatively more associated with routines, this time finding more meaningful results.

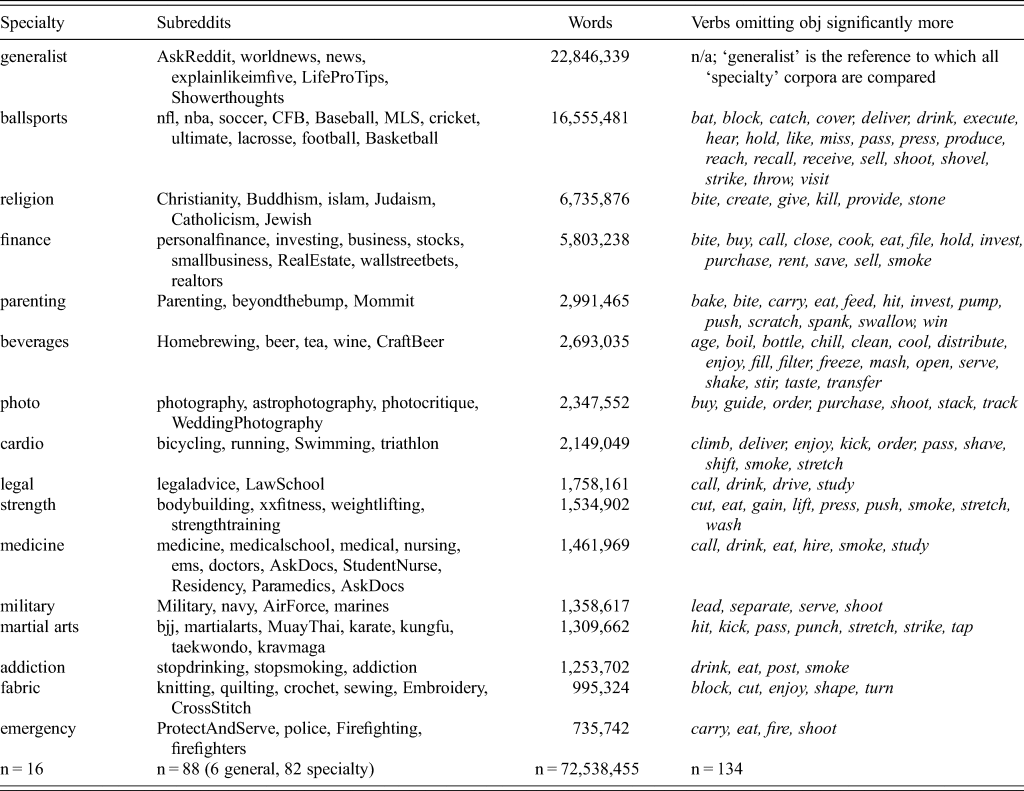

3.3 Comparing across generalist versus specialty subreddits

In addition to the data from generalist subreddits, I further collected tokens of transitive verbs with and without objects from 82 specialty subreddits grouped by hand into 15 culturally diverse specialties (for example, r/bodybuilding, r/xxfitness, r/ weightlighting, and r/strengthtraining were grouped into a ‘strength’ specialty, which yields more data than if each small subreddit were taken alone). Table 2 presents all of the specialty subreddits grouped by speciality and listed in decreasing order of size.

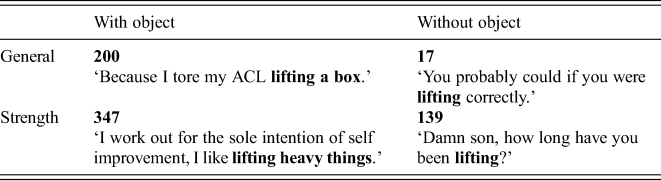

Using the process for identifying tokens of verbs with and without objects described above, including the labor-intensive hand-correction (section 3.1), I compared the proportion of tokens of each transitive verb with and without an object in each specialty corpus compared to the generalist corpus (as for lift in table 1).

Table 1. Fisher test showing that the proportion of object-omitting uses of lift differs significantly between generalist and strength-specialty subreddits

For each verb and each specialty corpus, such a contingency table was used in a Fisher Exact Test (a more exact cousin of the χ2 test) to determine whether the proportion of object omissions differs significantly between the specialty corpus and the generalist one. In table 1, lift indeed omits its object significantly more often in the strength specialty (p < 0.001).

Ultimately, this process yields a dataset of 134 verbs across 15 specialties found to omit their objects significantly more often (p < 0.05) in those specialty corpora. These verbs are listed in table 2.Footnote 11 The online Appendix provides an example object-omitting sentence for each verb; the full data are available at https://osf.io/kxe3u/

Table 2. ‘General’ and ‘specialty’ Reddit corpora; the subreddits they comprise; their total word count; and the 134 verbs significantly more often omitting objects in the specialty corpora compared to the generalist one

Impressionistically, some of the verbs in table 2 indeed seem to describe community-specific routines, while others are more debatable. Some verbs polysemously take on a narrower sub-sense within a given community: for police officers, carry involves guns; for photographers, shoot involves photographs; for martial artists, tap means tapping on a mat to end a fight. Such polysemy is consistent with the claim that verbs are more disposed to omit their objects in the communities in which they are more strongly associated with a routine: if a verb describes a routine in a particular community, then it takes on a narrower sense to describe that routine.

Other verbs already robustly omit their objects in generalist subreddits (perhaps because they already describe routines in mainstream society?), but omit their objects even more often in certain specialty subreddits. People interested in personal finance discuss the cost of eating out or cooking at home, while fitness enthusiasts eat to achieve health goals; sports fans drink while watching a game, while those battling addiction try not to; law students discuss studying.

While I did not attempt to distinguish between ‘definite/anaphoric’ and ‘indefinite/existential’ object omission in corpus data, some tokens clearly map onto those categories. In discussions of religion and finance, bite is anaphoric to a discourse-given topic (okay, I'll bite) – whereas parents instruct their children not to bite people in general. For beer-brewers, bottle and chill describe steps in a recipe, perhaps anaphoric to a discourse referent, and perhaps introducing a confound that recipes particularly favor object omissionFootnote 12 – though many object-omitting tokens have first-person subjects (I sold my kegging setup and went back to bottling) rather than the second-person imperatives used in recipe instructions. Among sports enthusiasts, I like! is used to comment on a development in a discourse-given sports game. In contrast, many other object-omitting tokens would be paraphrased using non-anaphoric objects: lift (weights), shoot (photos/guns), shift (gears), pump (breastmilk). Still other object-omitting tokens blur the boundary between ‘definite/anaphoric’ and ‘indefinite/existential’, illustrating why I did not attempt to separate these: for sports fans, do catch, throw and pass refer to the discourse-given ball, or to balls in general? For those interested in finance, does file refer to one's specific taxes or to taxes in general?

In all these ways, the object-omitting verbs that emerge from specialty subreddits are quite heterogeneous. But rather than using my own judgment to exclude some of them, I keep all of them to explore what they tell us quantitatively.

There is no quantitative metric for routine. But one might expect that generalists would discuss lifting all sorts of things, while strength enthusiasts would discuss lifting weights in particular; and that strength enthusiasts would use the verb lift more often than generalists. In other words:

(5) The Comparative Routine → Selection Hypothesis: If a verb is more strongly associated with a routine in Community A compared to Community B, that verb should more strongly select its object in the speech/writings of Community A.

(6) The Comparative Routine → Frequency Hypothesis: If a verb is more strongly associated with a routine in Community A compared to Community B, that verb should occur more frequently in the speech/writings of Community A.

(7) The Comparative Routine → Omission Hypothesis:

(a) If a verb is more strongly associated with a routine in Community A compared to Community B, that verb should omit its object more often in the speech/writings of Community A.

(b) If a verb omits is object more often in the speech/writings of Community A compared to Community B, then that verb should be more strongly associated with a routine in Community A (and thus, by (5) and (6), should more strongly select its object and occur more frequently in the speech/writings of Community A).

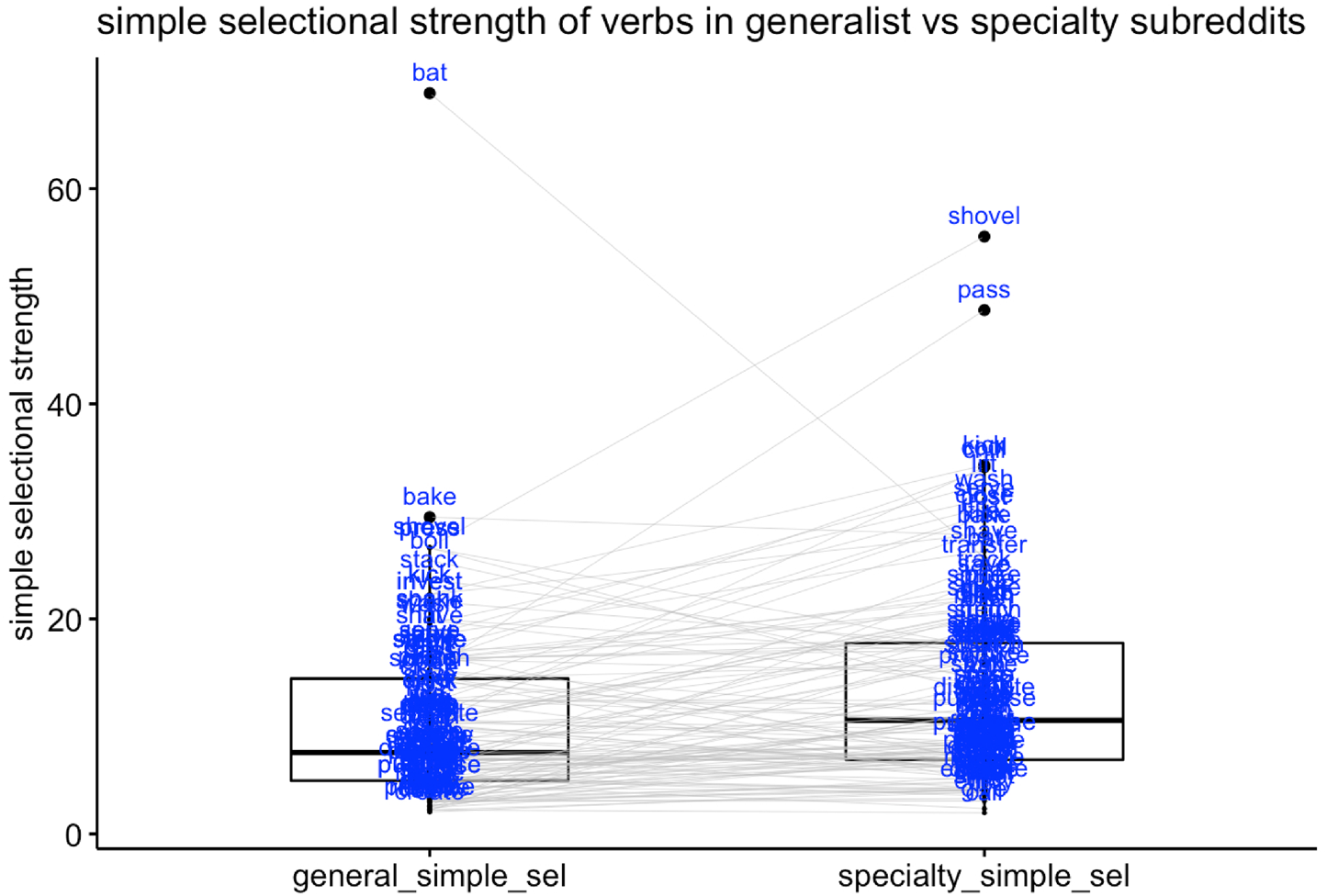

To test part (7b) of the Comparative Routine → Omission Hypothesis with respect to selection, figure 1 plots the ‘simple’ selection of these verbs in both the generalist corpus and in the speciality corpus where they omit their objects significantly more often; figure 2 plots their selectional strength calculated using Resnik's formulation. According to a Wilcoxon test for paired samples in R (Wilcoxon Reference Wilcoxon1945), these verbs have significantly (p < 0.001) higher selection in the specialty subreddits, using both metrics of selection, compared to the generalist onesFootnote 13 – consistent with part (7b) of the Comparative Routine → Omission Hypothesis.

Figure 1. Comparing the selection of 134 verbs in both generalist subreddits and in the specialty subreddits in which they omit their objects significantly more often, using ‘simple selection’ (of all the times that the verb appears with an object, what percentage of the time does it occur with its most common lemmatized, non-pronoun object?) (in generalist subreddits, bat strongly selects eyes/eyelashes)

Figure 2. Comparing the selection of 134 verbs in both generalist subreddits and in the specialty subreddits in which they omit their objects significantly more often, using Resnik's selection metric. Note that in generalist subreddits, bat strongly selects eyes/eyelashes; and that bite appears multiple times on the right side of the graph because it omits its object more often in religion, finance and parenting specialties compared to generalist subreddits

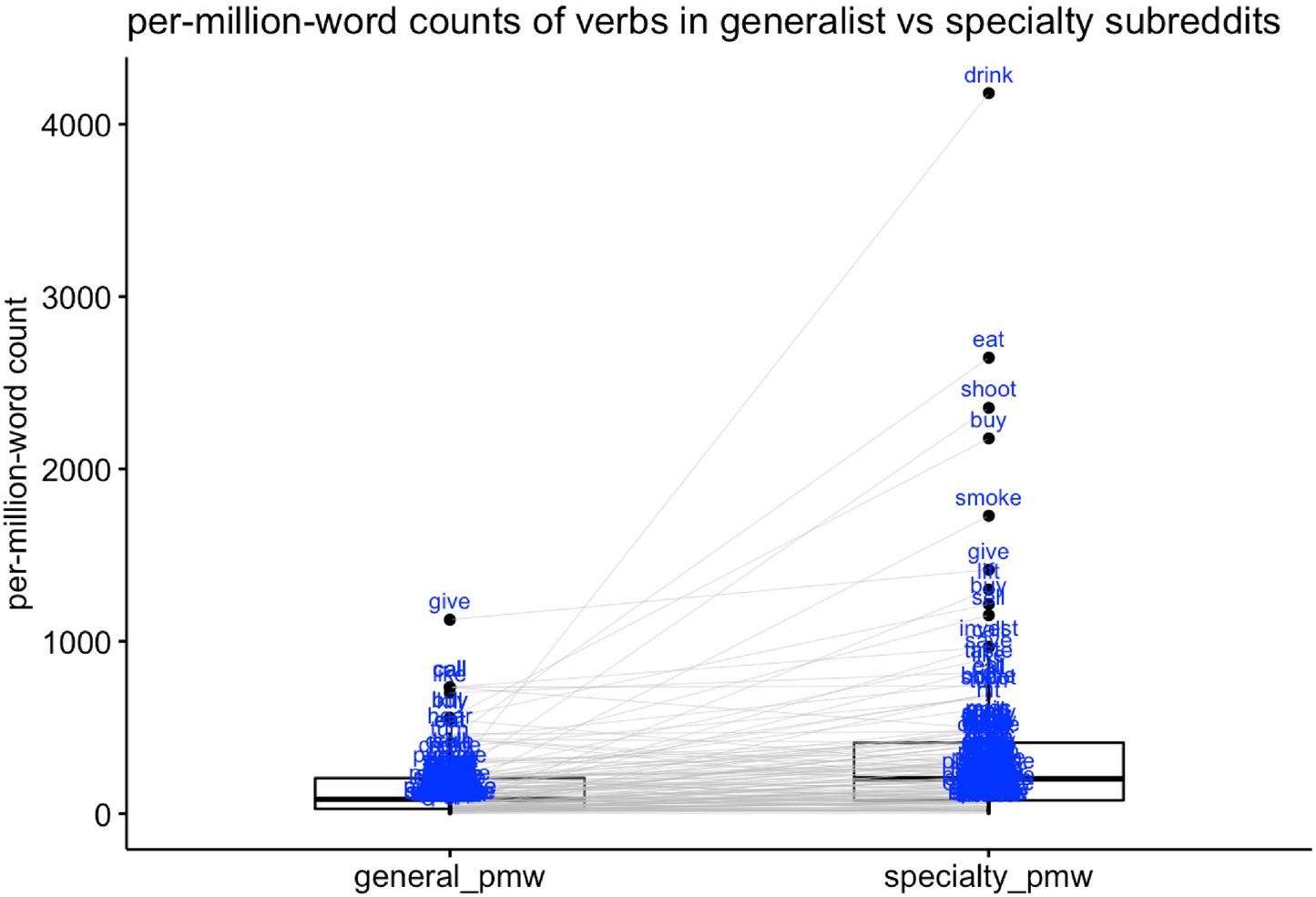

To test Part (7b) of the Comparative Routine → Omission Hypothesis with respect to frequency, figure 3 plots the per-million-word frequency of these verbs in both the generalist corpus and in the speciality corpus where they omit their objects significantly more often.Footnote 14 These results are also highly significant in a Wilcoxon test for paired samples (V = 1488, p < 0.0001): verbs are much more frequent in the specialty subreddits where they omit their objects more often, consistent with Part (8b) of the Comparative Routine → Omission Hypothesis.

Figure 3. Comparing the per-million-word frequency of 134 verbs in both generalist subreddits and in the specialty subreddits in which they omit their objects significantly more often

It is also notable that fully 61 percent of all object-omitting verb tokens are -ing gerunds in specialty subreddits (bottling), whereas only 23 percent of tokens with objects are gerunds (see the online Appendix for data). Gerunds straddle the border between verbs and nouns (Malouf Reference Malouf1998), so perhaps it is not surprising that gerunds allow object omission more freely than other verb forms. Semantically, too, progressive gerunds are more common with aspectual activities than with other aspectual classes (Shirai & Andersen Reference Shirai and Andersen1995), so this finding is also consistent with the proposed analysis (section 5) of object-omitting verbs as activities describing the routine actions of an agent.

Expanding the data considered in the literature on object omission, these results are consistent with the claim that verbs omit their objects more often in the communities where they describe routines. But without a direct metric for whether a verb describes a routine in a corpus or not, the evidence is still somewhat indirect. Therefore, the next section uses an experimental setup to target the notion of routine directly.

4 Experiments

Two experiments are presented, one crossing routine with selection (Experiment 1) and one crossing routine with frequency (Experiment 2), both consistent with the hypothesis (adapted from (7) above) that routine itself facilitates object omission:Footnote 15

(8) The Comparative Routine → Omission Hypothesis [empirically supported]: If a verb is more strongly associated with a routine in Community A compared to Community B, that verb should (be judged by experimental participants to) omit its object more easily in the speech/writings of Community A.

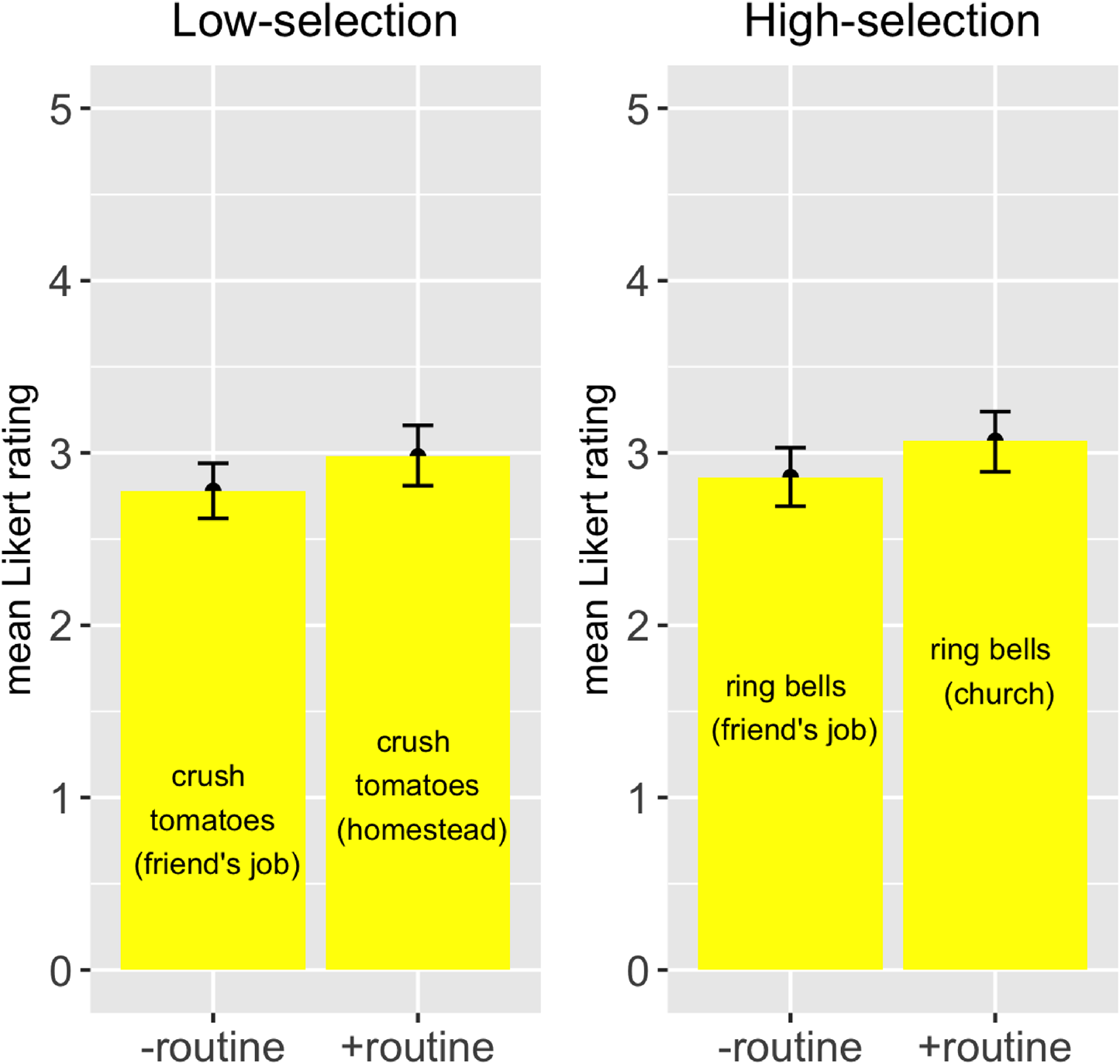

4.1 Experiment 1: Routine versus selection

Experiment 1 used items of the form in (9), each one randomly assigned to a high-routine or low-routine condition. A narrator tells a three-sentence story about their day using a past-tense transitive verb with an object; then participants rate on a five-star Likert scale the likelihood of that narrator using a past-tense, episodic, object-omitting form of that verb.

(9) Your friend Helen tells you about her day:

(a) (High-routine condition:) I worked at my homestead. Just like I always do, I crushed some tomatoes. Then I made sauce.

(b) (Low-routine condition:) I visited a friend's job. Just because people wanted me to try it, I crushed some tomatoes. Then I took some photos.

The next time Helen talks about crushing tomatoes the day before, how likely do you think she is to say the following?:

‘I crushed yesterday.’ ✩✩✩✩✩

In the high-routine condition, the first sentence mentions a workplace where the action described by the verb might be undertaken routinely (people might crush tomatoes at a homestead or ring bells at a church); the second sentence indicates that the speaker engages in this action regularly; and the final sentence describes another related activity. In the low-routine condition, the first sentence mentions a friend's job (evoking no particular routines); the second sentence indicates that the speaker pursues the action only haphazardly; and the last sentence describes an unrelated activity.

The target verb is chosen from among eight verbs of moderate frequency – all in the middle 50 percent of verbs by frequency in the generalist Reddit data, and all normally resistant to object omission. Half of these verbs come from the top quartile with respect to their selectional strength in the generalist Reddit data (ring strongly selects bells), and half from the bottom quartile (tomatoes are one of many diverse objects that can occur with crush). These verbs are intended to hold frequency relatively constant, allowing comparison of weaker and stronger selection.

Eight items like (9) were presented on Qualtrics in a random order and interspersed with ten fillers (all given in the online Appendix). A total of 130 participants using United States I.P. addresses were recruited via Amazon's Mechanical Turk with an official IRB exemption from my institution, paid $1.20 for a median work duration of less than six minutes; after being advised that they would be paid regardless of their answer, all but two indicated their native language to be English, leaving 128 participants for analysis.

Data were analyzed using a mixed-effects linear regression model in R (lmer; Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015), predicting rating (on a continuous 1–5 scale) as a function of selection, routine and their interaction, with random intercepts for both items and participants.Footnote 16 This model (table 3; figure 4) finds that high-routine items have statistically significantly higher ratings than low-routine items. No effect is found for selection nor for any interaction of selection with routine, from which nothing can be concluded. But the finding for routine is consistent with the hypothesis (8) that routine, separated from selection and with frequency held constant, facilitates object omission.

Figure 4. Mean Likert rating of object omission for high versus low ‘selection’ and high versus low ‘routine’ conditions

Table 3. Model's predictions for Likert rating of object omission of ‘rating’ based on selection, routine and their interaction (results also replicate in an ordered categorical regression, treating Likert stars as ordered but not linear)

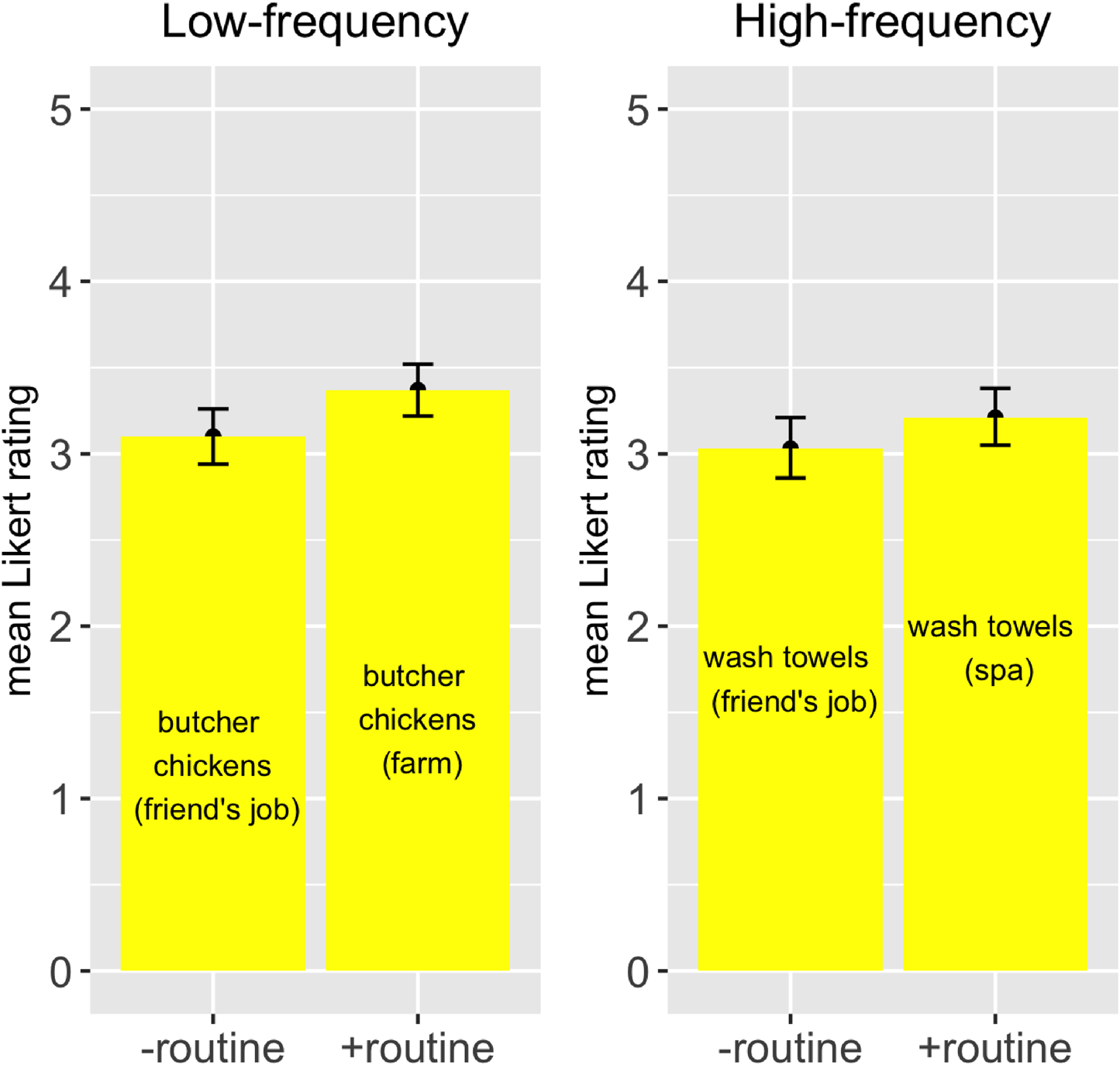

4.2 Experiment 2: Routine versus frequency

Experiment 2 parallels the design of Experiment 1, with items (10) randomly assigned to a high-routine condition (people might routinely butcher chickens at a poultry farm or wash towels at a spa) or a low-routine condition (a friend's job).

(10) Your friend Caroline tells you about her day:

(a) (High-routine condition:) I worked at my poultry farm. Just like I always do, I butchered some chickens. Then I gathered some eggs.

(b) (Low-routine condition:) I visited a friend's job. Just because people wanted me to try it, I butchered some chickens. Then I went for a walk.

The next time Caroline talks about butchering chickens the day before, how likely do you think she is to say the following?:

‘I butchered yesterday.’ ✩✩✩✩✩

The target verb is chosen from among eight verbs of moderate selectional strength – all in the middle 50 percent of verbs by selection in the generalist Reddit data. Four of these verbs come from the top quartile in the generalist Reddit data with respect to frequency (close, wash), and four from the bottom quartile (butcher, replenish).

Eight items (given in the online Appendix) were presented on Qualtrics in a random order, interspersed with the same ten fillers as in Experiment 1. A total of 130 self-identified-native-English-speaking participants with United States I.P. addresses were recruited via Amazon's Mechanical Turk, none of whom participated in Experiment 1.

Parallel to Experiment 1, data were analyzed using mixed-effects linear regression models in R, predicting rating (on a continuous 1–5 scale) as a function of frequency, routine, and their interaction, with random intercepts for both items and participants.Footnote 17 Also parallel to Experiment 1, this model (table 4; figure 5) finds that high-routine items have significantly higher ratings than low-routine items. No effect is found for frequency, nor for any interaction of frequency with routine. In sum, Experiment 2 is consistent with the hypothesis (8) that routine, separated from frequency, facilitates object omission.

Figure 5. Mean Likert rating of object omission for high versus low ‘frequency’ and high versus low ‘routine’ conditions

Table 4. Model's predictions for Likert rating of object omission of ‘rating’ based on selection, routine, and their interaction (results replicate in an ordered categorical regression, treating Likert stars as ordered but not linear)

5 Semantic representation of object omission

Semantically, this article adopts the analysis of Levin & Rapaport Hovav (Reference Levin, Hovav, Pensalfini, Turpin and Guillemin2014): a change-of-state verb such as lift or clean is polysemous between a transitive change-of-state verb (11a) and an intransitive activity verb (Allerton Reference Allerton1975; Mittwoch Reference Mittwoch1982; Velasco & Muñoz Reference Velasco and Muñoz2002) describing the routine actions of an agent conventionally associated with bringing about that change of state (12a). For other object-omitting verbs that do not describe changes of state (surface contact verbs such as punch and hit; consumption verbs such as eat), the verb already describes an agent's activity, one which also (typically) involves a theme argument; without an object, such a verb is analyzed to describe an agent's routine actions without specifying a theme.

(11)

(a) [x CAUSE [BECOME [y <STATE>] (Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Rappaport Hovav, Levin, Butt and Geuder1998)

(b) Alice lifted weights.

(c)

$\exists e[ {lift( e ) \wedge agent( {e, \;Alice} ) \wedge theme( {e, \;weights} ) } ] $

$\exists e[ {lift( e ) \wedge agent( {e, \;Alice} ) \wedge theme( {e, \;weights} ) } ] $

(12)

(a) [x ACT <MANNER>] (Rappaport Hovav & Levin Reference Rappaport Hovav, Levin, Butt and Geuder1998)

(b) Alice lifted.

(c)

$\exists e[ {lift( e ) \wedge agent( {e, \;Alice} ) } ] $

$\exists e[ {lift( e ) \wedge agent( {e, \;Alice} ) } ] $

To interpret an object-omitting token (12b), the hearer's task is not to recover any missing object (as argued by, e.g., Cote Reference Cote1996), but instead to infer the routine associated with the verb – to understand that, for strength-training enthusiasts, lift describes a routine of exercising with weights. To the extent that such a routine is common knowledge between speaker and hearer, the object-omitting token can be produced and interpreted. As for the much-discussed contrast between eat and devour, this analysis posits that eat is associated with a routine in our culture, whereas it is less clear what routine is described by an object-omitting token of devour.

By analyzing object-omitting tokens as intransitive (Fodor & Fodor Reference Fodor and Fodor1980, with no theme argument in the framework framework of Davidson Reference Davidson and Rescher1967; Parsons Reference Parsons1990), this analysis captures the fact that omitted objects vary widely: in terms of how they would be paraphrased; how specifically they can be inferred; and even whether they exist at all (in the context of martial arts drills, I kicked may describe an event with no patient) – difficult to capture if all omitted objects shared a single, silent semantics such as existential quantification (Recanati Reference Recanati2002). Instead, true to what is pronounced, there is no semantic object, but one may be conceptually inferred (Rice Reference Rice1988) depending on the routine described.

6 Synthesizing related work

The main claim of this article – that verbs describing routines facilitate object omission – explains at most one part of a complex phenomenon. Many other elements play a role too: the subject/agent, the omitted object/theme, the tense/aspect/modality and structure of the full sentence, and the larger discourse (Cote Reference Cote1996).

A verb may facilitate object omission if its subject/agent is affected by participating in the event described by the verb, or if the object/theme goes in or out of existence as a result of the verb event (Næss Reference Næss2011), on the grounds that such sentences are associated with lower transitivity on the prototype scale of Hopper & Thompson (Reference Hopper and Thompson1980). Generic, habitual, modal, progressive, and negated sentences – also associated with lower transitivity on the scale of Hopper & Thompson (Reference Hopper and Thompson1980) – favor omission more than regular episodic sentences do (Fellbaum & Kegl Reference Fellbaum, Kegl, deJong and No1989; Cote Reference Cote1996; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2001, Reference Goldberg, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005; Mittwoch Reference Mittwoch, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005). While it is difficult to automatically identify generic/habitual tokens, the easily-identified class of verbal gerunds (how long have you been lifting?) are indeed over-represented among object-omitting tokens in the Reddit studies (see online Appendix). Sentences involving contrastive focus also favor omission (Fellbaum & Kegl Reference Fellbaum, Kegl, deJong and No1989; Cote Reference Cote1996; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2001, Reference Goldberg, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005); you push and I'll pull). And of course, object omission takes place within a discourse, so it is shaped by what has already been said, and what speakers and hearers believe and care about (Groefsema Reference Groefsema1995; Cote Reference Cote1996; Goldberg Reference Goldberg2001, Reference Goldberg, Erteschik-Shir and Rapoport2005; Scott Reference Scott2006). All of these elements must come together for a full account of object omission in English.

While object omission is influenced by many forces, I would like to suggest that some classic insights are derived from the claim that verbs more readily omit their objects when they describe routines.

There is a longstanding idea that an object can only be omitted if it can be somehow recovered (Lehrer Reference Lehrer1970; Rice Reference Rice1988; Cote Reference Cote1996); Resnik formalizes this idea by quantifying the information that a verb provides to recover its object (selection). But if recoverability facilitates object omission, then it is not clear why objects resist omission when they are easily recovered from the discourse rather than from the verb: did you like the film? / I loved sounds odd in English, even though the object is recoverable. If recoverability facilitates object omission, then it is also puzzling why a verb such as devein – strongly associated with shrimp in corpora – does not readily omit its object (?I deveined today; Ruppenhofer Reference Ruppenhofer2004). But that observation is easily explained if routine drives omission, since devein does not constitute a routine for most speakers. (And if chefs who regularly devein shrimp do say I deveined today, that is further evidence consistent with the routine analysis.) On this analysis, recoverability and selection do not themselves drive object omission, but instead appear to be associated with omission because object-omitting verbs describing routines are regularly used with the objects involved in those routines (the Routine → Selection Hypothesis).

As for Goldberg's suggestion that frequency drives object omission, I would like to suggest that the real driver of object omission is routine, roughly correlated with relative frequency. Comparing across corpora, a verb is more likely to omit its object in the corpus where it is more strongly associated with a routine; and is also likely to be more used more frequently in the community where it is more strongly associated with a routine (the Routine → Frequency Hypothesis).

It has also been observed that object-omitting verbs tend to evoke a narrower range of objects than those that can appear with the verb overtly (Fillmore Reference Fillmore1986). I ate evokes a meal rather than a raisin; I lifted evokes weights rather than boxes. This observation is derived if object-omitting verbs evoke the objects involved in their associated routines: a routine associated with lift for fitness enthusiasts involves weights. Because routines vary across communities and time, this analysis further explains why object omission may be judged differently by different speakers, and makes synchronic and diachronic predictions about where it may emerge.

7 Conclusion

Object omission has attracted decades of interest because it requires us to disentangle syntax, word meaning, discourse and world knowledge (Cote Reference Cote1996; Velasco & Muñoz Reference Velasco and Muñoz2002); and because our desire for far-reaching explanations conflicts with the messiness of the data – where we observe differences within near-synonyms as well as across languages. Seeking regularity in this realm, this article has offered both production and perception evidence consistent with the claim that verbs facilitate object omission when they describe routines. A corpus study comparing specialty to generalist subreddits finds evidence consistent with the claim that verbs omit their objects more often in the communities where they are more strongly associated with a routine – illustrating the value of natural language processing tools and social media data for studying linguistic theory and grammatical variation (e.g. Bamman et al. Reference Bamman, Eisenstein and Schnoebelen2014; Acton & Potts Reference Acton and Potts2014; Futrell et al. Reference Futrell, Mahowald and Gibson2015). Experiments show that when routine is crossed with selection and with frequency, and all other factors held constant, routine drives object omission. Semantically, object-omitting tokens are analyzed as intransitive aspectual activities describing the routine actions of an agent, which must be familiar to both speaker and hearer.

Most broadly, this article offers evidence that language, down to its structure, is fundamentally social. The syntax of verbs is argued to be shaped by the conventions of the people who use those verbs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674321000022