The city of El Perú-Waka’ (Figure 1)—referred to henceforth as Waka’ (Guenter Reference Guenter2007; Martin Reference Martin and Trejo2000:116)—in northwestern Peten, Guatemala, was a politically and economically strategic kingdom, given its geographic position atop a massive escarpment overlooking the juncture of two major riverine arteries across the Peten (the San Pedro and San Juan Rivers). Because of this, it was drawn into the political rivalry between the Classic-period Kaan regime and its Tikal adversaries. A handful of Waka's documented carved monuments relate aspects of this history. These details, when woven into the city's archaeological record, narrate the strategies employed by individuals who were directly engaged in these struggles. Among various figures mentioned, we focus on two royal women and how they linked the Kaan regime with the Wak polity. We examine the political and diplomatic nature of their roles in crafting Waka's place in the overarching narratives of alliance and conquest during the sixth through the early part of the eighth centuries. We argue that the uniquely rich and complementary pairing of archaeological and textual data surrounding Ix Ikoom (in the sixth century) and Lady K'abel (primarily during the seventh century) provides an invaluable opportunity to interrogate the nature of women's prominence with respect to Kaan regime-building strategies during these centuries.

Figure 1. Map of Waka’ core area. Map by Damien Marken. Figure courtesy of the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala.

In our modeling, we look to recent work on the nature of political systems, both in terms of their resiliency and their fragility (McAnany Reference McAnany and Yoffee2019), which helps us conceive of how these political orders were framed and how factions competed. Certain aspects of the stranger-king model (Graeber and Sahlins Reference Graeber and Sahlins2017; see also Iannone Reference Iannone, Iannone, Houk and Schwake2016) are attractive because its proponents do not distinguish between politics and cosmology but rather view these as intertwined domains—features that are consistent with Mesoamerican ontologies. We focus here on the element of outsider marriage practices employed in that model (Graeber and Sahlins Reference Graeber and Sahlins2017).

Yet most indicative of stranger-kingship is the marriage of these powerful foreigners to native women—in the paradigmatic case, the union of the original stranger-king with the daughter or daughters of the autochthonous ruler—an alliance that is, in effect, the fundamental contract of the new society (Sahlins Reference Sahlins, Graeber and Sahlins2017:224)

However, we seek to modify and/or clarify three points. First, the powerful foreigners, in this case, are the women. It is with them—not the daughters of the local nobility—that local male rulers are wed, and it is through such arrangements that powerful polities become subordinate to the multipronged regime known as Kaan, with which these women are affiliated. In consideration of the model and its use of the term “stranger-kings,” we operate with the term “queen.” We follow Nelson's (Reference Nelson and Nelson2003:1) use of this term as one broadly defined to encompass “the various roles” held by “women in public leadership.” It is also a term that appropriately characterizes their elevated status in these hypogamous marriages (see also Lamoureux-St-Hilaire Reference Lamoureux-St-Hilaire2018:452; Marcus Reference Marcus1976:163–164; Martin Reference Martin2020:183–190). Our focus on these royal women of the Kaan realm and their roles in the rise of that regime during the sixth through the early part of the eighth centuries not only encourages more holistic consideration of Kaan's development but also contributes to a robust literature on the political lives of women in the ancient Maya world and Mesoamerica more broadly (e.g., see Ardren Reference Ardren2002, Reference Ardren2008; Joyce Reference Joyce2000; Miller Reference Miller1988; Spores Reference Spores1974).

Second, we briefly address the concept of “foreigner” or “stranger,” which Graeber and Sahlins (Reference Graeber and Sahlins2017) utilize as derivative from ethnological work across vastly distinct sociogeographic pre-state societies. From within a Mesoamerican perspective, the concept of a stranger may not itself be fully understood because ethnicity and identity and their rootedness to a geographic locality are still very much the subject of widespread discussion (Beyyette and LeCount Reference Beyyette and LeCount2017). Confusion about ethnicity and ancient identity among the Maya may be compounded by scholars’ expanded use of the Yukatek endonym maya to refer to a tremendously diverse population— geographically and linguistically—on the basis of shared cultural traits, including but not limited to artistic conventions and expressions, cosmovision, symbol systems, and social structures. This Yukatek word (Restall Reference Restall2004) would not have been utilized or indeed understood in antiquity in the way scholars use it today. Our reliance on this term to reference shared cultural traits across vast distances, may mask—to outside researchers—the degree to which distinctions in ethnicity, language, identity, and loyalty existed. Recent research, however, by Joanne Baron (Reference Baron2016) and others (Christenson Reference Christenson2003; Lacadena and Wichmann Reference Lacadena, Wichmann and Wichmann2004; Watanabe Reference Watanabe1990) on patron deities and how they reflect both the identity with and the attachment people have to a particular place provides insights on how regional identities were strongly rooted to place and the fact that factionalism was a potential outcome of such distinctions in the ancient Maya world (Brumfiel and Fox Reference Brumfiel and Fox2003). In the context of such factionalism and regional distinction, women from a northerly region would be the strangers to the southerly region of ancient Peten.

Third, the stranger-king model, proposed by David Graeber and Marshall Sahlins (Reference Sahlins, Graeber and Sahlins2017:315–325) is based largely on dynastic kingship, although they do feature queens in some instances. We assert that this blood-lineage form of succession is but one strategy that may have been in operation in Mesoamerica throughout the Classic period (Carballo Reference Carballo, Hirth, Carballo and Arroyo2020), and variable institutions of succession may have been one basis for this Maya Lowland factionalism during the sixth through eighth centuries. Indeed, although not the subject of this article, there is an emerging discourse in our discipline recognizing the possibility of multiple and competing models of authority and that this may have been a basis for the factionalism that characterized both Early and Late Classic political histories across the region (see Freidel and Rich Reference Freidel, Rich, Renfrew, Morley and Boyd2018; McAnany Reference McAnany and Yoffee2019). Although we acknowledge that the model is far more expansive, we limit our focus to the element of outsider marriage. We consider the role of the Kaan-affiliated women at Waka’ as the strangers of high status marrying into the local lineage (for more extensive cross-cultural comparison, see Navarro-Farr, Kelly et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Kelly, Rich and Robles2020). We argue that because these women pertain to distinct generations during the rise of Kaan, the data surrounding them provide a unique opportunity to interrogate how they helped shape Kaan's political hegemony over time.

Prelude: The political landscape

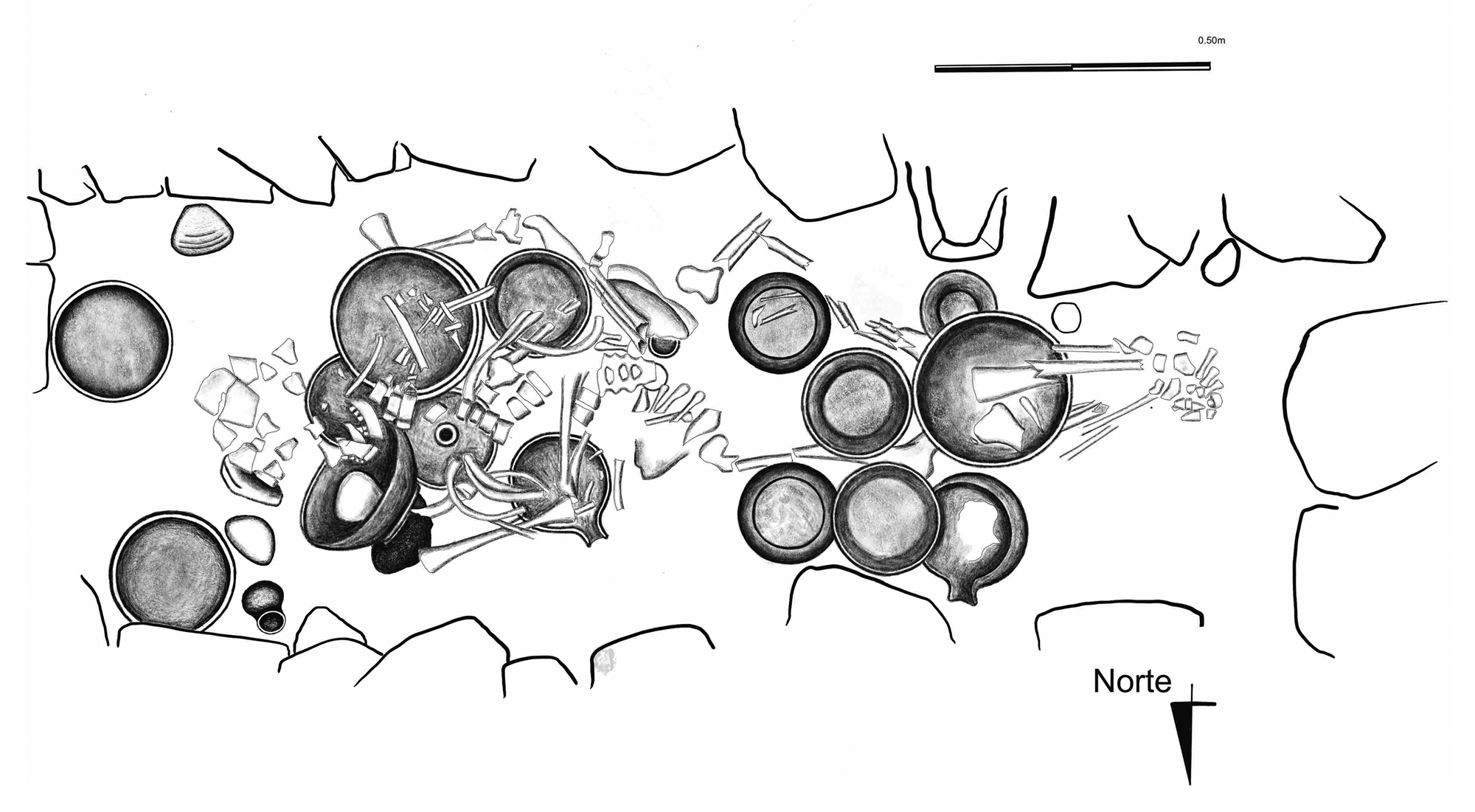

Although the primary events relevant to our discussion are those of the Kaan regime's political machinations in the sixth through eighth centuries a.d., we briefly contextualize the role of Waka’ in the broader historical narrative. Textual evidence indicates that Waka's royal dynasty was probably founded in the second century a.d. (Guenter Reference Guenter, Escobedo and Freidel2005, Reference Guenter, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014). Although Classic dynasties, like those of Tikal and Naranjo, later boast of the deep antiquity of their dynasties (Martin Reference Martin, Traxler and Sharer2016), Tikal's dynastic founder, Yax Ehb Xook, likely lived in the late first or early second century a.d. (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008) and is evidently the first dynast with archaeological remains in Burial 85 in the North Acropolis (Coe Reference Coe and Willey1965, Reference Coe1990). A Wak dynasty king, “Leaf” Chan Ahk is probably the early fourth century a.d. king in Waka’ Burial 80 (Figure 2) discovered by Griselda Pérez and Juan Carlos Pérez in the Palace Acropolis (Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Pérez and Pérez2018; Pérez Robles et al. Reference Pérez Robles, Pérez Calderón and Freidel2020). Although not likely the first Wak-dynasty king, he is, currently, the oldest dynast to be discovered in Peten outside Tikal (see Źrałka et al. Reference Źrałka, Jarosław, Koszkul, Martin and Hermes2011 for another early king in Peten). We therefore propose that the Wak dynasty is presently second to the Tikal dynasty as an institutional presence in Peten and likely an ally and trade partner to that emerging realm (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Auld-Thomas, Arredondo, Hirth, Carballo and Arroyo2020:382–384: Figure 12.3). This early connection was strengthened during the late fourth century entrada, when Waka’ hosted Sihyaj K'ahk’ on his route to Tikal (Stuart Reference Stuart, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000).

Figure 2. Burial 80, the tomb of an early fourth-century a.d. Waka’ ruler. Drawing by Juan Carlos Pérez and Griselda Pérez Robles. Figure courtesy of the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala.

Waka’ was therefore an important ally, targeted by Kaan leaders not only because of its strategic location at the juncture of two trade routes—the east–west route linking Tikal to Teotihuacan as mentioned, and the north–south route connecting the lowlands with the highlands, from which many prestige items were sourced (Canuto and Barrientos Q. Reference Canuto and Barrientos Q.2013; Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Escobedo, Lee, Guenter, Meléndez, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2007)—but also for its historical prominence in the region. Kaan regime rulers subsequently prosecuted a long-term campaign of both military and diplomatic imposition of hegemony on kingdoms in Peten, beginning at least in the early sixth century (Freidel and Guenter Reference Freidel and Guenter2003; Martin Reference Martin2008; Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008). We argue that the key diplomatic features of this campaign involved stranger-queens who married into the local lineage.

Maya stranger-queens: A brief contextual history

Ix Ikoom and Lady K'abel of Waka’ were in the company of other powerful Maya queens who married into foreign royal bloodlines (Freidel and Guenter Reference Freidel and Guenter2003; Martin Reference Martin2008; Navarro-Farr, Kelly et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Kelly, Rich and Robles2020; Reese-Taylor et al. Reference Reese-Taylor, Mathews, Guernsey, Fritzler, Orr and Koontz2009; Vázquez López Reference Vázquez López2017). Martin (Reference Martin2020:183) states that at least 35 exogamous marriages, or 15% of the total number of known or assumed marriages, are recorded in the inscriptions, although substantially more may have existed. Many of the prominent exogamous marriages involve women who have Kaan affiliation either by bloodline or political ties. It is noteworthy that there are three Kaan princesses, each of distinct generations, who are celebrated on La Corona Panel 6, previously known as the Dallas Altar (Figure 3; see also Martin Reference Martin2008). Other renowned Kaan queens include the mother of Bird Jaguar IV at Yaxchilan (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008:128) and Ix Wak Jalam Chan, who, although the daughter of the factional Dos Pilas ruler, married into the Naranjo royal line under the auspices of Kaan, and therefore astutely emphasized those political affiliations (Helmke Reference Helmke2017; Martin Reference Martin2020:177). These women were part of a cohort whose role was to connect the Kaan regime with the polities of the south (Reese-Taylor et al. Reference Reese-Taylor, Mathews, Guernsey, Fritzler, Orr and Koontz2009:62). Martin acknowledges that these and other women married off to foreign rulers were “not necessarily passive players” (Reference Martin2020:183); however, we take an even stronger view: these women were decisive and agential leaders deeply familiar with how to maneuver the politics within which they were enmeshed. Martial engagement and prowess, as proposed by Reese-Taylor et al. (Reference Reese-Taylor, Mathews, Guernsey, Fritzler, Orr and Koontz2009), is one role associated with some that are portrayed with overt battle imagery such as captives or shields. Beyond this, we argue that the queens of Waka’ bore responsibilities to their adoptive home's patron deities, intimately connecting them to the local religious traditions. Their arrival was frequently marked with the verb huli, a verb that “often heralds a transformative event… suggest[ing] that these arrivals are politically transformative” (Canuto and Barrientos Q. Reference Canuto, Barrientos Q., Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020:184–185; see also Martin Reference Martin2020:121–128; Stuart Reference Stuart, Carrasco, Jones and Sessions2000). We therefore take the use of this verb in association with their arrival as further testament to their political power and agency.

Figure 3. La Corona Panel 6, Dallas Museum of Art, The Eugene and Margaret McDermott Art Fund, Inc., in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Frederick M. Mayer. Image courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art. 1988.15.McD.

As rulers, these women were doubtless considered strangers by the men and women of their courts and by their people at large. Marshall Sahlins writes of stranger-kings as a worldwide structural phenomenon of sacred rulership and as “an alliance that is in effect the fundamental contract of a new society” (2017:224). In the context of La Corona queens, Lamoureux-St-Hilaire (Reference Lamoureux-St-Hilaire2018:452) proposes that Kaan hegemonic strategies applied this stranger-kingship practice but with “gender role reversal,” in which the women were the crucial connection. We propose that Maya queens who ruled as paramounts and not just as consorts were “strangers” not merely in the fact that they were from a region of some distance farther to the north but, more critically, because of their being both female and paramount in authority. The definitive nature of their authority (and their mandate) resided not only in their diplomatic responsibilities to enmesh cities along major trade arteries through marriage diplomacy (after Teufel Reference Teufel and Grube2008) but through their role as conjurers, diviners, and embodiments of deities. This pattern of female co-rule may have been another “stranger” concept in a region in which the institutional landscape more often reflected males as the more visible founders of political order. This contrasts with the north, which Reese-Taylor et al. (Reference Reese-Taylor, Mathews, Guernsey, Fritzler, Orr and Koontz2009) suggest more often employed ambilineal descent. Rather than male dominance as the default social order, the politics of descent reckoning in the north were more fluid.

Kaan-affiliated queens of Waka’

Two powerful queens ruled at Waka’. In the sixth century, Ix Ikoom bore the titles ix sak wahyis and k'uhul “cha”tahn winik, and in the late seventh and early eighth centuries, Lady K'abel bore the titles ix kaan ajaw and ix kaloomte’. Following Martin's (Reference Martin2020:67–101) recent work on titles and their transmission, we believe that titles are naming traditions that link an individual in complex ways to both to a lineage and a geographic location, as we discuss below. We identify them as strategic Kaan regime agents and powerful co-rulers of Waka’. Our evidence derives from contextual analyses of inscriptions, grave goods, and the collective human actions that situated these contexts, anchoring these women in Waka's social memory.

Ix Ikoom

The first of these Kaan-affiliated women at Waka’ is Ix Ikoom. We consider her political position, gleaned from evidence surrounding how she was remembered, both epigraphically and from the offerings placed in her tomb during interment and upon re-entry. The evidence therefore underscores her role as an ancestress revered by Lady K'abel and K'inich Bahlam II.

Epigraphy

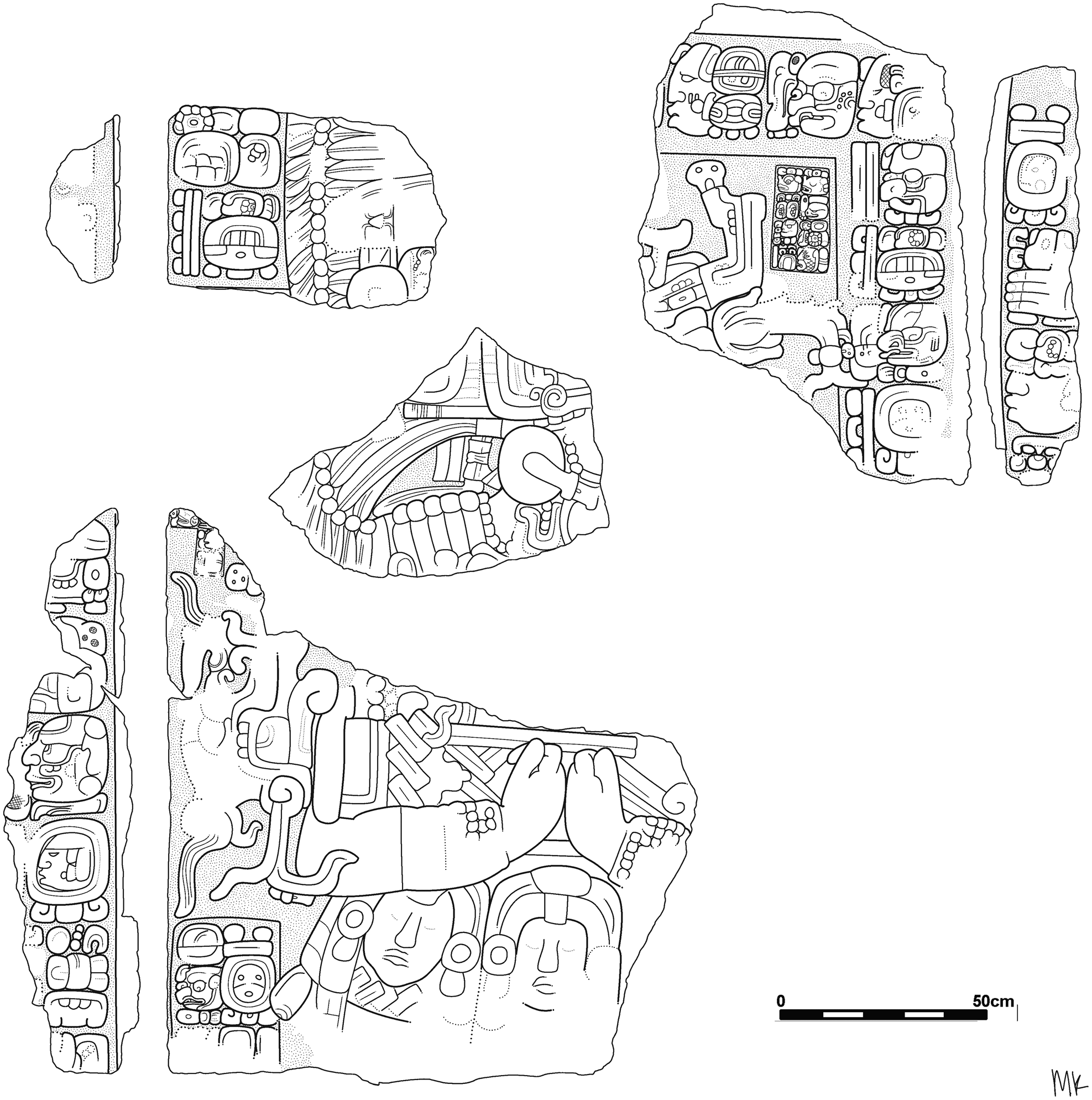

Two hieroglyphic monuments, dating to eras a century and a half apart, point to the prominence of a sixth-century woman connected to Kaan but integrated into the Wak dynasty. Her name comes to us from Stela 43 (Figure 4), of which fragments were reset into the terminal fronting platform or adosada terrace walls of Waka's main civic-ceremonial shrine, Structure M13-1 (Navarro-Farr, Eppich et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Eppich, Freidel, Robles, Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020, Navarro-Farr, Pérez-Robles et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Robles, Menéndez, Pérez Calderón, Stanton and Brown2020). Here, her name is spelled out IX-i-ko-ma yo-?, ix ikoom ?, the last glyph of which has not been deciphered. Consequently, we call her simply Ix Ikoom (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Navarro-Farr, Freidel, Pérez Calderón and Pérez Robles2024; Pérez Robles and Navarro-Farr Reference Pérez Robles, Navarro-Farr, Calderón and Freidel2013). The next glyph block gives her title, IX-SAK-WAY, ix sak wahyis, which is connected with allies of Kaan and, in particular, the site of La Corona (Canuto and Barrientos Q. Reference Canuto, Barrientos Q., Houk, Arroyo and Powis2020:178–179; García Barrios Reference García Barrios2011; Grube Reference Grube2013:130–131). Stela 43, dating to a.d. 702, was erected long after Ix Ikoom's death. It portrays K'inich Bahlam II wielding the ceremonial bundle. The mention of Ix Ikoom recalls her engaged in some unknown event in a.d. 573. This event, as well as two others, are associated with 7 Ahau period ending dates that appear on the stela. Although the associated verbs are all unknown, we infer that the act she performed in 573 was significant and recalls her role as a revered ancestress.

The second mention of this woman was found on Stela 44 (Figure 5), discovered inside Structure M13-1 (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Navarro-Farr, Freidel, Pérez Calderón and Pérez Robles2024; Pérez Robles and Navarro-Farr Reference Pérez Robles, Navarro-Farr, Calderón and Freidel2013). This monument was reset to align with Structure M13-1's reestablished centerline and incorporated into the penultimate adosada phase; that same phase had been built to encompass the tomb of Lady K'abel. Stela 44, carved in a.d. 564, only a decade before the unknown event on Stela 43, identifies a woman by the same ix sak wahyis title seen on Stela 43. The visible part of her name associated with this title on Stela 44 does not include the IX-i-ko-ma yo-? glyph sequence we saw on Stela 43, although we may be missing part of her name. Nevertheless, we believe that the close overlap in time and the use of the ix sak wahyis title on both texts strongly suggests that this is one and the same woman. Her name is given as a part of the longer parentage statement of Wa'oom Uch'ab Ahk, who lists his father as Chak Tok Ich'aak, and goes on to give his own accession date in a.d. 556. That both of the monuments known to mention Ix Ikoom at Waka’ occur at Structure M13-1 underscores the importance of linking her historical narrative to Lady K'abel, whose remains were interred in an earlier phase of the same building. Moreover, the two mentions of this earlier queen and her ix sak wahyis title, used frequently at the nearby Kaan ally of La Corona, point to her Kaan affiliation. In fact, an additional title given to her on Stela 44, k'uhul “cha”tahn winik, further associates her with Kaan elite (Velásquez and García Barrios Reference Velásquez García and Barrios2018). These discoveries chronologically and materially connect with the archaeology of Burial 8, the interment of a royal woman discovered in 2004 (Lee Reference Lee2012; Lee and Piehl Reference Lee, Piehl, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014).

Figure 4. El Perú Stela 43: fragments feature the Waka’ ruler Kinich Bahlam II. Illustration by Mary Kate Kelly. Figure courtesy of the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala.

Figure 5. El Perú Stela 44, featuring the Waka’ ruler Chak Tok Ich'aak. Illustration by Mary Kate Kelly. Figure courtesy of the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala.

Archaeology

Burial 8 was situated directly under the floor of the central room of an audience building at Waka's northwest palace acropolis (Figure 6). Burial 8 was sexed as female based on the width of the pelvis’ sciatic notch (Piehl Reference Piehl, Escobedo and Freidel2006). The remains were placed atop a wooden bier that was itself atop a stone dais with complex ritual deposits on and around it. The cranium and femora had been removed (Piehl Reference Piehl, Escobedo and Freidel2006) in a clear act of ancestor veneration (Lee Reference Lee2012; McAnany Reference McAnany1995, Reference McAnany and Houston1998), but much of the lower torso, forearms, and hands, were still in place. Strontium data demonstrated values overlapping with Waka’ and Calakmul (Piehl Reference Piehl, Escobedo and Freidel2006), although it was not definitive for either locale. The tomb was left open as a shrine during the eighth century, mimicking Copan's Margarita tomb (Bell Reference Bell and Ardren2002). David Lee (Reference Lee, Escobedo and Freidel2005) determined that the tomb was accessed through a hole in the floor of the summit room, the focal structure and reception area in the Palace's upper patio.

Figure 6. Burial 8, the tomb of the sixth-century a.d. queen Ix Ikoom. Illustration by Mary Jane Acuña, Sarah Sage, and Evangelia Tsesmeli. Figure courtesy of the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala.

Dating

Burial 8 included 23 ceramic vessels that feature a majority of sixth- or early seventh– century types with two items (a miniature Chablekal Grey tripod and a huunal jewel; Figure 7) clearly dating to the eighth century (Lee Reference Lee2012). This chronological mix, although consistent with the pattern of an open tomb, nevertheless complicates dating the remains. A dearth of carbonized materials and insufficient collagen in the human remains made radiometric dating impossible (Lee Reference Lee2012). The Burial 8 materials on and around the stone dais were significantly disturbed when the tomb was discovered. David Lee (Reference Lee2012; Lee and Piehl Reference Lee, Piehl, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014) argued that the queen had been laid to rest in her jade finery on a wooden bier placed on the stone dais and that much of the resulting pattern of deposition in the space between the dais and the tomb's west wall was caused by cascading debris following deterioration and collapse of the bier. The wooden bier, by this argument, had to have extended out from the dais so that, upon its deterioration, the materials atop it fell to the tomb floor below, along the western wall of the chamber where archaeologists located them. Based on the taphonomy of the associated materials and their position, Lee reasoned that the tomb was that of a late queen, possibly Ix Pakal, who ruled Waka’ in the late eighth century. Lee believed that most of the earlier sixth-century vessels were incorporated relics.

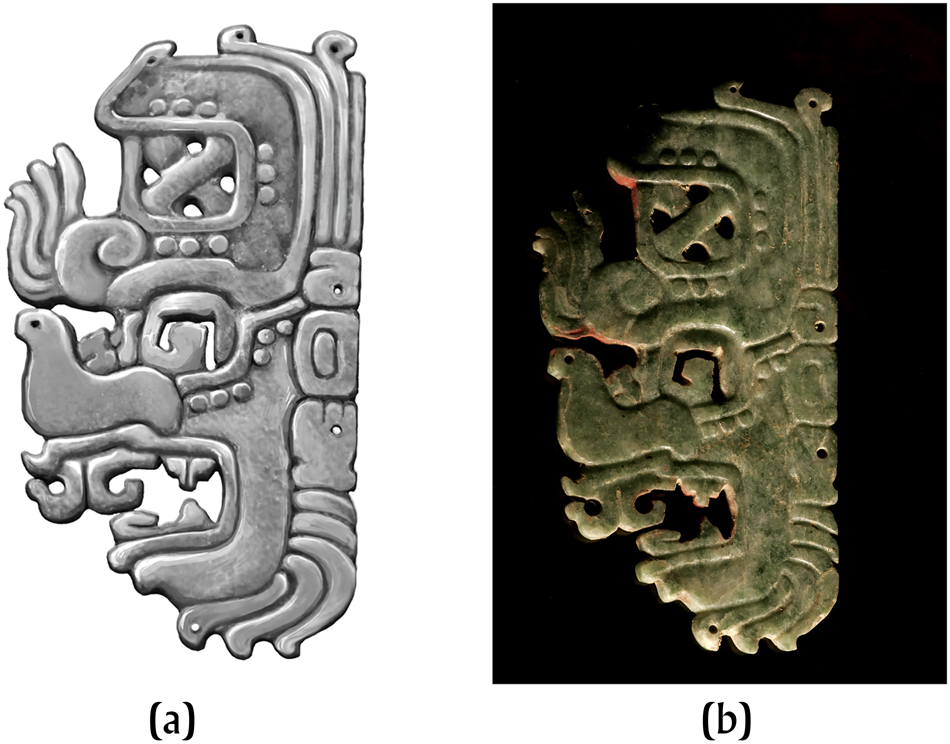

Figure 7. Huunal jewel: (a) illustration by Sarah Sage; (b) photo by Patrick Aventurier. Figure courtesy of the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala.

We argue that the resulting artifact rearrangement was deliberate and part of the eighth-century reentry, and that the artifact patterns left on the dais and below it were intentional rather than the result of the deterioration of the bier. This alternative interpretation was supported by project ceramicist Keith Eppich (Reference Eppich2013), who noted the strong correlation between the vessels of Burial 8 and Burial 37, which was a sealed tomb discovered in 2006 (Escobedo and Meléndez Reference Escobedo, Meléndez, Escobedo and Freidel2007) that dates to the sixth century a.d. Specifically, he notes that the vessel forms, surface treatment, and types from Burials 8 and 37 were so similarly rendered as to indicate that they pertained to the same typological category and, therefore, to the same chronological period. He argues that the later-dating materials were included in the context of subsequent reentry event(s). Juan Carlos Meléndez (Reference Meléndez2019) has since argued that Burial 37 is the tomb of Wak-dynasty king Chak Tok Ich'aak, who died in a.d. 556. Stela 44, mentioned earlier, lists this ruler and Ix Ikoom in the parentage statement associated with Wa'oom Uch'ab Ahk, indicating that she was likely his mother and therefore wife to Chak Tok Ich'aak. The weight of evidence therefore indicates that Burial 8 contains the remains of Ix Ikoom. She was placed in a sacred sanctuary into which eighth-century supplicants later reentered, placing important funerary offerings, including the huunal, while removing sacred remains for bundling before leave-taking acts of high ceremony.

Several archaeological and epigraphic patterns underscore the importance of this royal woman for sixth-century Waka’, a period during which the city transitioned politically away from Tikal and, according to Stela 44, was now under the sway of Kaan (see also Martin and Beliaev Reference Martin and Beliaev2017). Her husband is identified on Stela 44 as Chak Tok Ich'aak and given the title wak ajaw, which names him as the lord of Waka’. Stuart and colleagues (Reference Stuart, Canuto, Barrientos and González2018) believe, and we agree, that a second reference to this same Chak Tok Ich'aak is found on La Corona Altar 5, where he is given the title sak wahyis (see also Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Navarro-Farr, Freidel, Pérez Calderón and Pérez Robles2024). As mentioned earlier, this is a title frequently found at La Corona and intimately affiliated with the Kaan regime. Although the details are murky regarding his reign over La Corona and Waka’—whether simultaneous or sequential—the role of his wife, Ix Ikoom (as noted above, also connected to La Corona with her sak wayhis title), must have been significant during this period. If Chak Tok Ich'aak was simultaneously responsible for both Waka’ and La Corona, Ix Ikoom must have been pivotal to the rule of Waka’ during that period, particularly in times of his absence. If her arrival to Waka’ as his wife postdates his rule at La Corona, we know from Stela 43 that she maintained an active role for at least 17 years after the death of her husband, performing an unknown but certainly significant event in 573 that was recorded reverentially 129 years later.

Ample material evidence indicates the degree of her influence at the site as well, both in the form of her interment and the ritualized manner of its reentry generations later. Indeed, an impressive array of jade and shell artifacts was discovered adorning the queen (Figure 8). Many were also recovered between the stone dais and the western or rear wall of the tomb. Perhaps the most impressive among that array was the large string-sawn jade huunal, with a profile deity head rendered in an eighth-century style (Fields Reference Fields, Robertson and Fields1991; Schele and Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986). Analyses of microtraces of manufacture on that jewel (Meléndez Reference Meléndez2019; Melgar Tisoc and Andrieu Reference Melgar Tisoc, Andrieu, Arroyo, Salinas and Άlvarez2015, Reference Melgar Tisoc, Andrieu, Pérez and Pérez2016) indicate that it was made with obsidian grit polish, a distinctive method of crafting jade from La Corona, 30 km north of Waka’. This jewel style is represented in carved depictions of eighth-century kings at the site of Machaquila in southeastern Peten (Just Reference Just2007), all of whom are titled kaloomte’.

Figure 8. Various jades adorning Burial 8 (jades not arranged in situ). Photo by Patrick Aventurier. Figure courtesy of the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala.

Archaeologists also discovered a large inverted red basin with a large ovoid kill hole placed over the abdomen, where the hands and wrists were crossed. A concentration of shell tokens and whole shells were clustered under the basin. Among these, archaeologists recovered three jades carved in the form of the glyph for ik’ (spirit, breath, wind) concentrated by the hands underneath the basin. The inverted basin is the womb signature of the young Moon/Water Goddess at Teotihuacan on the Tepantitla Mural (Pasztory Reference Pasztory1976; Robb Reference Robb2017) and is generally associated in Postclassic Maya imagery with the old goddess Chak Chel (Milbrath Reference Milbrath1999). In Classic-period inscriptions, the inverted water jar is an insignia of noble women (Grube Reference Grube2012).

Lady K'abel

The second Kaan-affiliated woman in Waka’ history is Lady K'abel, a figure who has long been known from El Perú-Waka’ Stela 34, which is on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art (Guenter Reference Guenter, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014; Wanyerka Reference Wanyerka1996).

Epigraphy

There are two artifacts that name Lady K'abel in the archaeological record of Waka’: Stela 34 (Figure 9) and a small alabaster lidded jar (Figure 10a) discovered in Burial 61 (see Guenter Reference Guenter, Escobedo and Freidel2005, Reference Guenter, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014; Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Olivia, Robles, Pérez Calderón, Menéndez Bolaños, Patterson, Eppich and Kelly2021; Wanyerka Reference Wanyerka1996). Stela 34 shows her donning elaborate regalia and attended by a dwarf. This monument was originally paired with Stela 33, which portrays her husband, K'inich Bahlam II, whose monument is located at the Kimbell Art Museum.

Figure 9. El Perú-Waka' Stela 34, depicting Lady K'abel. Front Face of a Stela (Free-standing Stone with Relief), 692. Mesoamerica, Guatemala, Department of the Petén, El Perú (also known as Waka’), Maya people (a.d. 250–900). Limestone; 274.4 x 182.3 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1967.29.

Figure 10. Illustration of Burial 61 featuring a selection of tomb offerings: (a) alabaster jar (photo by Griselda Pérez); (b) Burial 61, the tomb of Lady K'abel (illustration by Olivia Navarro-Farr based on photogrammetry by Francisco Castañeda); (c) tubular jade bead (photo by René Ozaeta); (d) Don Gordon–molded carved snuff jar (photo by Francisco Castañeda); (e) stuccoed mirror (photo and illustration tracing by René Ozaeta); (f) zoomorphic figurine (photo by Juan Carlos Pérez); and (g) anthropomorphic figurine (photo by Juan Carlos Pérez). Figures courtesy of the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala.

Stela 34 is carved with great skill on a fine limestone that preserved much of the original detail, including two examples of her name, IX- “waterlily-hand” (-le). It is composed of ix, meaning “lady,” and a second element that depicts a hand holding a waterlily, which has not been deciphered but has been provisionally read as K'AB (hand), resulting in her nickname ix k'abel, or Lady K'abel, although it almost certainly does not read as such. She is also given two titles: ix kaan ajaw, indicating her status as a member of the Kaan regime, and ix kaloomte’, a very high-ranking title understood to be hierarchically above ajaw (lord). On this monument, Lady K'abel is said to be portrayed in the act of impersonating the Waterlily Serpent (see Houston and Taube Reference Houston, Taube, Isendahl and Persson2011:31, n4; Stuart Reference Stuart2007). Martin (Reference Martin2020:184) also notes that the text references her “arrival” through use of the term huli, although the date is missing.

The second artifact bearing her name was discovered in Burial 61, carved on a small alabaster jar (Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Olivia, Robles, Pérez Calderón, Menéndez Bolaños, Patterson, Eppich and Kelly2021; see also Figure 10a). The four-glyph inscription names the jar as the yotoot (container) for some as-yet undeciphered object or substance and gives her name as the owner of the jar with the same IX-“waterlily-hand” that was found on Stela 34, along with her ix kaan ajaw title. This was clearly a personal item owned by Lady K'abel, and its inclusion in Burial 61 (Figure 10b) strongly supports the identification of the individual therein as Lady K'abel herself.

Archaeology

Elements of Lady K'abel's story are embellished by rich contextual evidence from varied mortuary contexts at Waka’. One of these sources of narrative contextual data comes from an intricate figurine scene buried in the tomb of a Waka’ ruler (Burial 39; for more on this tomb, see Rich Reference Rich2011) whose funeral, according to the narrative scene, Lady K'abel and Yuhknoom Ch'een II apparently presided over (Freidel and Rich Reference Freidel, Rich, Renfrew, Morley and Boyd2018). Yuhknoom Ch'een II, then ruler of Calakmul, was also the overseer of the accession of K'inich Bahlam II and father to Lady K'abel (Martin Reference Martin2020:184). These figurines have since been scientifically affirmed through instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) (Rich et al. Reference Rich, Sears, Bishop and Reents-Budet2019) to have been produced with clay that has the same elemental composition as objects from Calakmul—including ceramics from Tomb IV of Temple II of that city, the tomb believed to house the remains of Yuhknoom Yich'aak K'ahk’ (Carrasco Vargas et al. Reference Carrasco Vargas, Boucher, González, Blos, Vierna, Moreno and Negrete1999). The figural funerary scene (Figure 11) features Lady K'abel in her youth, suggesting that she came as a young princess from Calakmul to Waka’ at the time of the death of the Wak king interred in Burial 39 around a.d. 657. This ruler, likely Bahlam Tz'am, was the predecessor of K'inich Bahlam II, the man she would marry and with whom she would share rulership (Rich Reference Rich2011; Rich and Matute Reference Rich, Matute, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014). We therefore posit that Lady K'abel comes to Waka’ with her father, presides with him over the funeral of the deceased Waka’ ruler (see also Freidel and Rich Reference Freidel, Rich, Renfrew, Morley and Boyd2018), and marries their successor. Importantly, this new Waka’ ruler was given the same regnal name as the king who was vassal to Sihyaj K'ahk’ centuries earlier—K'inich Bahlam I. The conferring of this name to the acceding Waka’ ruler under the auspices of Yuhknoom Ch'een II positions the latter, who conquered Tikal in 657, as akin to the conqueror Sihyaj K'ahk’; it conveys that he is repeating important history. His daughter Lady K'abel, like Ix Ikoom generations before, is the stranger-queen who co-rules at Waka’ during Kaan's seventh-century Golden Age. Evidence from her mortuary tableau both suggests that she became a beloved figure in her adoptive homeland and conveys how she skillfully navigated the politics of her time.

Figure 11. The figurine scene discovered in Waka's Burial 39, the tomb of a mid-seventh-century a.d. Waka’ ruler. Photo by Ricky López. Figure courtesy of the Dirección General del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Ministerio de Cultura y Deportes of Guatemala.

Because the data that speak to the identity of the interred both as a Kaan royal woman more generally and as Lady K'abel herself have been discussed elsewhere (Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Olivia, Robles, Pérez Calderón, Menéndez Bolaños, Patterson, Eppich and Kelly2021), we focus here on contextual analyses. We also consider the cosmological and martial implications for those accoutrements that are indicative of her political roles, with the understanding that warfare and cosmologies are deeply connected politically. To contextualize certain politically salient elements of Lady K'abel's funerary offerings and how we interpret these, we first reference the city's three patron deities, noted on Waka’ Stelae 16 and 44. This triad of patrons includes the Jaguar Paddler, an aspect of Akan the death god, and a moon deity. As argued elsewhere (Navarro-Farr, Kelly et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Kelly, Rich and Robles2020), her regalia—such as the bivalve xoc shell near her pelvis, spondylus bangles possibly adorning a cape, and her small paint jar possibly featuring an aged aspect of the moon deity—demonstrate her not only as a Kaan woman but as the embodiment of the moon goddess in her afterlife performance. This embodiment is typical for Kaan-origin royal women (Looper Reference Looper and Ardren2002; Reese-Taylor et al. Reference Reese-Taylor, Mathews, Guernsey, Fritzler, Orr and Koontz2009; Vázquez López Reference Vázquez López2017). Another salient element of her funerary offerings is a tubular jade jewel carved in the form of the face of an animate deity (Stuart Reference Stuart, Guernsey, Clark and Arroyo2010:295) situated near her midsection on her right side (Figure 10c).

A small snuff jar of the Don Gordon–molded type with pseudoglyphs on all sides (Figure 10d) was likely utilized to carry tobacco snuff (Eppich and Navarro-Farr Reference Eppich, Navarro-Farr, Loughmiller-Cardinal and Eppich2019). Various examples of this type of vessel exist in the Kerr archive, and strikingly similar ones were recovered in Copan's residential zone (Willey et al. Reference Willey, Leventhal, Demarest and Fash1994). Additionally, a recent publication (Card and Zender Reference Card and Zender2016) features a remarkably similar snuff bottle from the excavation of a seventh-century tomb at Tazumal, El Salvador. At Waka’, most snuff bottles occur in eighth-century contexts (Eppich and Navarro-Farr Reference Eppich, Navarro-Farr, Loughmiller-Cardinal and Eppich2019). The presence of the snuff jar in her burial further underscores Lady K'abel's responsibility for acts of sorcery (Wilbert Reference Wilbert1987).

In addition, her possession of one of the finest examples of a decorated mirror at Waka’ is suggestive of her role as a diviner. This specimen has a finely stuccoed backing (Figure 10e) with vibrant red and Maya blue paint and black-lined figures. The reconstructed image reveals a person seated above a giant centipede. The ancient Maya used mirrors to conjure visions of gods (Healy and Blainey Reference Healy and Blainey2011; Taube Reference Taube, Gallaga M. and Blainey2016). Seeing was essential to recording, and mirrors and plates were instruments for writing words and calculations that brought events and supernaturals into being (Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Masson and Rich2017). The linkage between divination and agriculture, warfare, and general well-being cannot be overstated in terms of its importance for a population as densely concentrated as Waka's was (Marken Reference Marken, Marken and Fitzsimmons2015). Adding to that, the political context of a polity with a mercurial history of shifting alliances geographically strategic to competing political interests situates the importance of effective rulership, for which divinatory prowess was critical.

Two small cave-stone effigies can be broadly considered nonhuman communicating objects (after Astor-Aguilera Reference Astor-Aguilera, Pugh and Cecil2009, Reference Astor-Aguilera2010). The zoomorphic figure (Figure 10f) appears to be a mammal—possibly a White-nosed coati (Nasua narica), with paws positioned as if holding a ceremonial bar and with stylized scrolls emanating from the mouth. These scrolls could represent any number of bodily essences, including breath, blood, or perhaps vomit. We posit that this figure might represent a wahy entity (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1989) or perhaps, more generally, a communicating object (Astor-Aguilera Reference Astor-Aguilera, Pugh and Cecil2009, Reference Astor-Aguilera2010).

The other figurine (Figure 10g), which was more crudely fashioned, was situated face down in the pelvic region, replicating a birthing position, with the head toward the western end of the chamber. Because this figurine has been described in detail elsewhere (Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Olivia, Robles, Pérez Calderón, Menéndez Bolaños, Patterson, Eppich and Kelly2021), it is sufficient to state that it is discernably anthropomorphic, is light bluish-gray in color, and has surfaces smoothed from frequent handling. The figure wields an axe with a blade at the right side of the neck, where red cinnabar paint offers the appearance of self-decapitation. We therefore identify this figure as an iteration of Akan (Grube Reference Grube, Behrens, Grube, Prager, Sachse, Teufel and Wagner2004; Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1998; see also Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Olivia, Robles, Pérez Calderón, Menéndez Bolaños, Patterson, Eppich and Kelly2021). This likelihood is underscored by the fact that an aspect of Akan is the most prominent of Waka's three patron deities. Moreover, epigraphic records convey that an effigy of this god was taken after the events of this interment during the Star War of Tikal's Yik'in Chan K'awiil against Waka’ in a.d. 743, described in Tikal Structure IV Lintel 3 (Martin and Grube Reference Martin and Grube2008). If this figure represents Akan, its inclusion in the birthing position suggests that it is being symbolically birthed by the city's queen in her death for all eternity. Although initially uncertain, we now believe Lady K'abel's tomb was reentered. We do not know whether this object may have been included as part of that event, in which case, its placement would signal the restoration of this deity to Waka’ via the birthing process. Alternatively, it may have been part of the original mortuary arrangement. In either case, its position is unmistakably one of birthing and therefore meant to underscore the queen's fertility and its associated power.

The small, lidded white alabaster jar bearing Lady K'abel's name as its possessor is shaped in the form of a nautilus shell on one side (Figure 10a). On the adjacent side, an aged human head emerges from the vessel. Below the emerging head appears the deliberately ambiguous rendering of an object that is either the figure's hand or a paint brush. This detail, plus the shell form, is further suggestive that this jar may have been used as Lady K'abel's paint container for rendering herself as a red-painted moon goddess. We interpret the aged figure as an aged aspect of the Moon Goddess (Navarro-Farr, Kelly et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Kelly, Rich and Robles2020), which likely references the queen's role as diviner, an activity also represented by the plate she bore across her left arm like a shield ornamented with painted divining tokens similar to those that occur as miniature spindle whorls in Waka’ Burials 38 and 39 (Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Masson and Rich2017). The jar was fractured on the side bearing the nautilus-shell carving. As noted, this tomb was likely reentered (Navarro-Farr et al. Reference Navarro-Farr, Olivia, Robles, Pérez Calderón, Menéndez Bolaños, Patterson, Eppich and Kelly2021). If so, this deliberate rupture may have been carried out in the context of that reentry event as a means to release the ch'ulel, or “soul force,” (Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Schele and Parker1993; Vogt Reference Vogt1969) therein. White alabaster cups were placed in the tombs of two other rulers: early fourth–century Burial 80 and sixth-century Burial 37, the tomb of King Chak Tok Ich'aak of Waka’. Although the “white soul flower cache vessels” (Fitzsimmons Reference Fitzsimmons2009; Freidel and Guenter Reference Freidel, Guenter, Guernsey and Reilly2006:76; Scherer Reference Scherer2015) of the Maya could take the form of jade earflares and other artifacts, it is possible that these white containers served this function at Waka’. Regarding the imagery, Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos (Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos2017:99–102) has recently cited similar examples of human emergence from shells as suggestive of intercourse and childbirth. The representation of birthing on a personal paint jar belonging to Lady K'abel is not an inconsequential association; rather, it is one that deliberately links her with the intrinsic power of her sex and her fecundity.

Lady K'abel's afterlife performance conveys her as a diviner, priestess, and conjurer of the city's patrons. Recent research has emphasized the broader ritual, political, and martial importance of conjuring and divinatory practice as tools for manipulating and leveraging elite power (Coltman and Pohl Reference Coltman and Pohl2021; Harrison-Buck and Freidel Reference Harrison-Buck and Freidel2021:3; Healy and Blainey Reference Healy and Blainey2011). Although the conjuring of patron deities is a task most commonly attributed to male rulers (Baron Reference Baron2016), we argue that, at its core, conjuring derives metaphorically from the acts of birthing and midwifery, which are uniquely female processes. The physical act of bringing life from the watery liminal womb into the terrestrial world is at once entirely commonplace while also utterly specific to the female body and, we argue, it is the metaphorical basis for ritual conjuring (see also Tate Reference Tate and Sweely1999; Taube Reference Taube and Ker1994; Vail Reference Vail2019). Associated instruments that underscore Lady K'abel's role as a powerful ritual conjurer include the mirror, the two effigies, the snuff jar, and the paint pot detailed above. Conjuring work establishes her as a critical political figure; her ability as a foreigner to conjure the local patron deities epitomizes her success at bridging the foreign with the local. Moreover, that Waka's patron deities—Akan and the Moon Goddess—figure so prominently in her mortuary performance reveals that Lady K'abel conveyed herself in death as intrinsic to Waka's protection and its people (after Baron Reference Baron2016) and would thus ensure the successful fusion of the stranger with the local. We surmise that in life it must have been so as well, given that the locus of her tomb was enshrined during Waka's gradual abandonment, with offerings representing the majority nonelite sectors of the population (Navarro-Farr Reference Navarro-Farr2009). Her marriage brokered an alliance between a critical vassal commanding a major trading nexus, which also had considerable historical significance as likely one of the oldest dynasties in Peten, with the most powerful Maya regime of the period.

Discussion

At the outset, we discussed outside marriage as the key element of the Graeber and Sahlins “stranger-king” model that we sought to interrogate in view of the data on Ix Ikoom and Lady K'abel. They describe these unions between foreign kings and local women as alliances to forge new societies (Sahlins Reference Sahlins, Graeber and Sahlins2017:224). That newness of society is relevant because it would seem to suggest that the first of such marriages between the stranger and the local gives rise to a new alliance of kinship that emerges through offspring (Sahlins Reference Sahlins, Graeber and Sahlins2017:185). The data on the Kaan queens, however, seems to depart from this notion in an important respect. There is not one foundational marriage alliance dependent upon the bonds forged from descendants; instead, there are successive marriages. This is clearly demonstrated in the retrospective texts on La Corona Panel 6 discussed above. It is also clear at Waka’ that we are not talking about one but two distinct and successive marriages between Kaan-affiliated royal women and Waka’ rulers. This suggests that bonds are formed through the actions of multigenerational marriage alliance rather than through (or in addition to) offspring; this is a key feature that further propels the importance of women in this regime. We posit that Kaan regime builders are expanding their hegemony through multigenerational marriage alliance because it reinforces the ontological creation principle of gender complementarity (Bassie-Sweet Reference Bassie-Sweet2000). The legitimacy of their regime is therefore made manifest by the arrival of Kaan women who marry local rulers.

One challenge the model poses is how and whether to define “stranger” in association with these queens given that conceptions of foreignness may not correlate squarely with geographic distance. Specifically, Lady K'abel arrives from a comparatively greater geographic distance (from Calakmul) than Ix Ikoom, who likely came to Waka’ from La Corona, only about 30 km away. Irrespective of whether distance informs on the degree to which each of these queens can be considered “strangers” in Graeber and Sahlins' model, neither woman is local to Waka’ or its immediate environs, nor did they use the local wak ajaw title. Yet they were both integrated into the city's physical and social memory, and they were both revered. Moreover, the archaeological and textual evidence demonstrates that they were exceptionally powerful and important to the Waka’ realm. In life, each held significant roles connecting the Kaan regime with the Wak dynasty and as powerful members of the Waka’ elite.

Ix Ikoom bore the titles ix sak wahyis and k'uhul “cha”tahn winik, affiliating her with La Corona and Kaan by extension. Her title of ix sak wayhis suggests that she was originally from La Corona and went to Waka’ to forge a dynastic relationship through marriage. This marriage to Chak Tok Ich'aak was likely the first in a series of multigenerational diplomatic arrangements connecting these kingdoms. The evidence that demonstrates Ix Ikoom's elevated status comes as much from indications during her lifetime (Stela 44 and Burial 8) as they do from retrospective remembrances (Stela 43 and the reentry into Burial 8). She is remembered on Stela 43, carved in a.d. 702—for her participation in the period-ending rituals in 573—on the occasion of the 7 Ahau k'atun ending, an event that appears to have been particularly important at Waka’. This monument was dedicated by Lady K'abel and her co-ruling spouse, K'inich Bahlam II, in part, as an active commemoration of Ix Ikoom as an earlier stranger-queen. We believe that this is an important claimed connection that we interpret as retrospectively incorporating her into an order of idealized Kaan stranger-queen personae that was well established by Lady K'abel's lifetime.

Lady K'abel is given the prominent titles of ix kaan ajaw and ix kaloomte’, and she is tasked with representing Kaan at Waka’ while also positioning herself as intrinsic to the well-being of the polity to which she is a stranger. Such work would also represent the completion of her journey—a task she conveys as accomplished in death. She travels in life to Waka’ as a young stranger from Calakmul (likely by way of La Corona). Once there, she presides over numerous pivotal ceremonies, one of the first of which was probably the funerary rites of the deceased predecessor in Waka's Burial 39. We believe, following Freidel and Rich (Reference Freidel, Rich, Renfrew, Morley and Boyd2018), that the individual in that tomb was also represented as the resurrected being in the narrative figurine scene included in that tomb. Those figurines, crafted in Lady K'abel's homeland, Calakmul, were likely brought with her as a gift to mark the ceremony. In this political union sealed with Lady K'abel's hypogamous marriage to K'inich Bahlam II of Waka’, it is important that we clarify that Lady K'abel and other Snake Queens in similar positions, including Ix Ikoom in her union with Chak Tok Ich'aak, were not mere commodities or pawns of exchange and alliance. Rather, they were central, agential, and responsible for doing their part as regime makers.

Their integral roles in the Wak dynasty are cemented in their mortuary remains, and their journeys from being strangers to revered queens are complete in death. They are thus rendered the cosmic bonds that link Kaan and Wak. Ix Ikoom was remembered as the Moon Goddess, indicated by the deliberate inversion of a ritually “killed” water basin atop a scattering of shell tokens and three ik’ jewels in her burial—evidence that we regard as materialized notation of this deific association (per Langley Reference Langley1991) and a feature consistent with her high status. Representations of Maya queens as the Moon Goddess have also been interpreted as having martial connotations, given that the moon is cyclical and associated with divinatory properties (Milbrath Reference Milbrath1995, Reference Milbrath1999; Nondédéo et al. Reference Nondédéo, García-Gallo and Cases Martín2019; Thompson Reference Thompson1939). Moreover, her treatment as revered ancestress, evident from both her inclusion on Stela 43 and the maintenance of her tomb as a site of ritual revisitations, is a further testament to the importance of her memory as a political glue binding the Wak dynasty to Kaan. This was later reinforced in the analogous role assumed by Lady K'abel from the seventh through the early eighth centuries. Given that the diadem jewel placed in Ix Ikoom's tomb was carved at another strong Kaan affiliate city, La Corona, during the eighth century, we view its inclusion as a further indication of the linkage between these Snake Queens and their counterparts at La Corona and likely elsewhere across the realm. In addition, Lady K'abel's own tomb bears evidence of her essential connection to the patron deities, Akan and the Moon Goddess. We interpret Lady K'abel's work as conjurer as being central to her role as a stranger-queen.

How could a queen simultaneously impersonate, wield, and even birth the deities of a patron city if she is foreign to that city? How could a foreign queen be expected to successfully conjoin two disparate kingdoms, one notably subordinate to the other, in ways that would resonate with the subordinate city's populace? In life, these queens took on the roles of priestesses to conjure and care for Waka's triad of patron deities while focusing efforts on the well-being of their new people. Their marriages and the unification of these two polities rendered the inhabitants of Waka’ people of Kaan. However well and good this symbology might have been for the sake of appearances, we believe that Ix Ikoom and Lady K'abel understood that the union of these polities had to have resonance for the people of this city. We believe their understanding of this, and their embodiment of this complicated role, is captured in their carefully planned mortuary tableaux. Moreover, both women were revered long after their deaths. Ix Ikoom's tomb was reentered and lain with additional offerings, and her actions were referenced on Stela 43 almost 130 years later. For Lady K'abel, the investigations of the reverentially enshrined (Navarro-Farr Reference Navarro-Farr2009) civic-ceremonial building within which she was entombed indicate that her endeavoring to be both Kaan and Wak proved successful and that attachment to sacred memory of her by elite and nonelite Waka’ folk endured for a century and a half after her death.

Conclusions

The archaeological and epigraphic data surrounding two foreign queens, Ix Ikoom and Lady K'abel, who ruled in distinct generations at Waka’ underscore their political and social importance. Consideration of outside marriage as a tenet of Graeber and Sahlins' (2017) stranger-kings model applied to these women and their marriages as stranger-queens yields deepened understanding of their place in the regime during the times in which they ruled. We see Lady K'abel as the quintessential stranger-queen, who arrives from a distant place to co-rule at the height of the regime she represented. She is conveyed as a powerful sorceress and the embodiment of the moon deity in her mortuary offerings. By comparison, we see that Ix Ikoom, who was herself a powerful and influential queen in her day, is commemorated in later years to position her in retrospect as Kaan queen predecessor to Lady K'abel. This affords insight into how the role of foreign queens—such as those of Ix Ikoom in the sixth century and Lady K'abel in the seventh and eighth centuries—evolved and became further concretized/codified over time, a position that has been advanced by Vázquez López (Reference Vázquez López2017). We hope that this research lends itself to further investigation into other aspects of the stranger-kingship model, such as the role and expression of divine rulership in the context of these women.

Ultimately, these strategies proved successful in that their influence persisted among those who revered them for the centuries that followed. These women held profound significance for the people of this ancient city. In later years, their significance was likely less about Kaan per se and more about the symbols of power and influence they wielded and how social memory surrounding their deeds and significance endured.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.