Introduction

The older adult segment of the population is growing at a faster rate than before (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020a). As such, healthy ageing has become a public policy priority (WHO, 2020a). During the 73rd World Health Assembly in August 2020, the WHO declared 2021–2030 the Decade of Healthy Ageing to encourage multi-sectoral and collaborative action to improve the lives of older adults (WHO, 2020a). Maintaining independent mobility is a component of healthy ageing. Mobility is a basic human need associated with independence, health and wellbeing (Goins et al., Reference Goins, Jones, Schure, Rosenberg, Phelan, Dodson and Jones2015). Mobility is also important for older adults wishing to ‘age in place’, defined as continuing to live in one's home or community with some level of independence, rather than in residential care as one ages (Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2011). Most older adults prefer to age in place, an option associated with increased independence, autonomy and connection to social networks (friends, family, neighbours), than relocating to residential care (Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2011). However, ageing in place requires an equilibrium between older adults’ competences (e.g. functional frailty) and their environment (e.g. housing modifications) (Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Windley and Byerts1982). To age in place successfully, older adults must also remain mobile to stay physically and mentally active, to access desired people and places, to meet their daily needs and to participate in social life (Luiu et al., Reference Luiu, Tight and Burrow2017).

Empirical evidence has found that older adults stay mobile through driving, particularly in the North American context (Davey, Reference Davey2007). However, not all older adults drive and as health problems arise many older adults must either reduce their driving or ‘give up the keys’ (Chihuri et al., Reference Chihuri, Mielenz, DiMaggio, Betz, DiGuiseppi, Jones and Guohua2016). Though the rate of Canadians who use public transit decreases with age, e.g. while 12.8 per cent of millennials use transit, only 5.1 per cent of Canadians aged 56–64 years and 3.1 per cent of those aged over 65 years use public transit (Newbold and Scott, Reference Newbold and Scott2018), transit has been put forward as an affordable and environmentally friendly way for older adults to maintain their independent mobility (Gilhooly et al., Reference Gilhooly, Hamilton, O'Neill, Gow, Webster, Pike and Bainbridge2002; Shrestha et al., Reference Shrestha, Millonig, Hounsell and McDonald2017).

In her article ‘Meeting transportation needs in an ageing-friendly community’, Sandra Rosenbloom (Reference Rosenbloom2009: 33) warned ‘there is little evidence that the United States is prepared to meet the mobility challenge facing older Americans’. She argued that part of the problem is many wrongly assume older adults will simply turn to public transit when they can no longer drive. The same challenge faces seniors in Canada today: there is little evidence that older Canadians take up transit as they age (Newbold et al., Reference Newbold, Scott, Spinney, Kanaroglou and Páez2005; Turcotte, Reference Turcotte2012; Newbold and Scott, Reference Newbold and Scott2018). In Rosenbloom's words:

Many assume that older people who face mobility problems or must cease driving will be served by public transit and by special demand responsive transportation services. Yet all indications are that neither traditional public transit services nor special demand services will come anywhere near meeting the mobility needs of the country's ageing population … There is no evidence that older people suddenly begin to use public transit upon retirement. In fact, there is far more evidence that older adults are even less likely to use public transit when they retire than when they are in the labor force … the overwhelming number of people now 65-plus probably never used public transit when in the workforce. (Rosenbloom, Reference Rosenbloom2009: 33)

In response to Rosenbloom's (Reference Rosenbloom2009) warning, the aim of this paper is to explore the processes of transitioning to public transit use as an older adult. Transitioning to a new travel mode is often a complex process; many continue to use other modes to meet all their travel needs (e.g. begin using transit to visit friends, but continue to drive to grocery shops). In this study, some participants suddenly became dependent on transit as their sole approach to travel, but most use transit as one of their many travel options. Further, we compare the experiences of those who have always used transit to those who begin using transit as older adults herein to shed light on the processes underlying this transition. Taken together, we concur with Rosenbloom and others (Newbold et al., Reference Newbold, Scott, Spinney, Kanaroglou and Páez2005; Turcotte, Reference Turcotte2012; Newbold and Scott, Reference Newbold and Scott2018) that ‘older people [do not] suddenly begin to use public transit’ (Rosenbloom, Reference Rosenbloom2009: 33). Instead, we argue that travelling using public transit as an older adult can involve the acquisition of skills, skills that are developed over time and through practice. Those with experience using public transit have already acquired these skills and can more easily maintain independent mobility as an older adult through public transport. We begin the paper by reviewing literature on travel behaviour change, focusing on public transit and literature on self-efficacy, the concept that theoretically frames this research. We then outline the methods used in our qualitative study on older adults’ experiences using transit. The Results section is divided into three sections exploring confidence, skill acquisition and how transit use self-efficacy can change over time. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications of the results, including a section on policy recommendations.

Literature review

As the negative externalities of car-dependent transportation systems on the environment and population health are becoming increasingly clear, there has been increased attention in research and public policy on how to encourage people to shift from travelling by car to more sustainable modes of transport including public transport, walking and cycling (Brog et al., Reference Brog, Erl, Ker, Ryle and Wall2009; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Delbosc and Currie2019). As such, a large body of work examines the processes underlying travel decision-making. Research suggests that people's decisions about how to travel are shaped by habits and routine (Banister, Reference Banister1978; Middleton, Reference Middleton2011; Beige and Axhausen, Reference Beige and Axhausen2012), which can be barriers to travel behaviour change (Ramadurai and Srinivasan, Reference Ramadurai and Srinivasan2006). Therefore, transitioning from private car to public transit, for instance in anticipation of driving cessation, may be particularly challenging for older adults who are accustomed to driving (Alsnih and Hensher, Reference Alsnih and Hensher2003; Adler and Rottunda, Reference Adler and Rottunda2006).

Many studies have focused on factors that influence travel behaviour change by disrupting habits. For instance, key events, such as retirement or becoming a parent, can disrupt individuals’ routines and make them susceptible to change their travel behaviour (Beige and Axhausen, Reference Beige and Axhausen2012; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Chatterjee, Melia, Knies and Laurie2014; Müggenburg et al., Reference Müggenburg, Busch-Geertsema and Lanzendorf2015; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Delbosc, Currie and Molloy2021). Retirement is one such event that has been found to influence older adults’ travel behaviour change. For instance, one study found that retirement results in reduced car use and mileage over time, even though car use for leisure purposes increases after retirement (Siren and Haustein, Reference Siren and Haustein2016). More broadly, Berg et al. (Reference Berg, Levin, Abramsson and Hagberg2014) argue that retirement alters people's space-time restrictions which influences their mobility demands and mode choice. Here, resources can be used to overcome such restrictions, such as becoming mobile through partners, friends and family, being able to walk or cycle, and the availability of services.

Other work has examined the travel behaviour change in response to external events, such as highway closures (Fujii et al., Reference Fujii, Garling and Kitamura2001) or ‘Ride to Work Day’ cycling events (Rose and Marfurt, Reference Rose and Marfurt2007). Further, the introduction of new transit services (Nordlund and Westin, Reference Nordlund and Westin2013) or the implementation of free passes (Gould and Zhou, Reference Gould and Zhou2010; Skarin et al., Reference Skarin, Olsson, Friman and Wästlund2019) have been found to encourage travel behaviour change. However, the process of travel behaviour change, or how one learns and habituates to new modes of travel, is still understudied in the literature (Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Delbosc and Currie2019). In fact, Müggenburg et al. (Reference Müggenburg, Busch-Geertsema and Lanzendorf2015) argue that theoretical understandings of travel behaviour change remain limited. This paper contributes to this field by exploring processes underpinning older people's transition to public transit use.

Understanding how older people transition to public transit use is important as many older adults experience driving regulation or cessation as they age. Foley et al. (Reference Foley, Heimovitz, Guralnik and Brock2002) estimate that Americans will outlive their driving days by six years for men and 11 years for women. The proportions of Canadians with a valid driving licence decreases dramatically with age: while 84.8 per cent of those aged 65–74 have a valid driving licence, this percentage drops to 61.3 per cent for the 80–84 age group and to 25.3 per cent for those aged 90 years or more (Turcotte, Reference Turcotte2012). Driving cessation is often a difficult and emotional transition associated with loss of independence, reduced mobility, social isolation and reduced self-esteem (Turcotte, Reference Turcotte2012; Haustein and Siren, Reference Haustein and Siren2014; Nordbakke and Schwanen, Reference Nordbakke and Schwanen2014; Dickerson et al., Reference Dickerson, Molnar, Bédard, Eby, Berg-Weger, Choi, Grigg, Horowitz, Meuser and Myers2019; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Newbold, Scott, Vrkljan and Grenier2020). Of course, these negative associations may be due to a lack of adequate transport alternatives to the car for older people in many western contexts (Alsnih and Hensher, Reference Alsnih and Hensher2003). For instance, research in small towns and rural areas near Hamilton found that a lack of transportation options resulted in dependency on private vehicles amongst older residents (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Newbold, Scott, Vrkljan and Grenier2020). Further, driving cessation is often preceded by a gradual process of driving regulation, a self-imposed reduction in driving to preserve safety and independence (e.g. only driving during daylight hours) (Goins et al., Reference Goins, Jones, Schure, Rosenberg, Phelan, Dodson and Jones2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Porter, Cull and Mazer2016; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Newbold, Scott, Vrkljan and Grenier2020). Both driving cessation and driving regulation have been found to result in reduced trip frequency and reduced participation in social activities (Nordbakke and Schwanen, Reference Nordbakke and Schwanen2014; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Newbold, Scott, Vrkljan and Grenier2020).

To understand better how older adults can maintain independent mobility by transitioning to public transit use, this paper draws on the physical activity literature's concept of self-efficacy, defined as ‘someone's belief in his/her capabilities to successfully execute necessary courses of action to satisfy situational demands’ (McAuley and Blissmer, Reference McAuley and Blissmer2000: 85). The relationship between self-efficacy and physical functional performance has been studied in the physical activity literature (McAuley and Blissmer, Reference McAuley and Blissmer2000; McAuley et al., Reference McAuley, Konopack, Morris, Motl, Hu, Doerksen and Rosengren2006). Specifically, self-efficacy has been found to be both a determinant and a consequence of physical activity: if one is confident in their ability to complete a task, they are more likely to do so, and as one completes tasks, one becomes more confident. Four factors influence self-efficacy: past accomplishments, social modelling, persuasion and physiological arousal (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1982; McAuley and Blissmer, Reference McAuley and Blissmer2000). Past accomplishments have been found to be the most influential in influencing self-efficacy (McAuley and Blissmer, Reference McAuley and Blissmer2000). People bring a wide variety of past experiences, some positive and some negative, with them when they complete a task. Past accomplishments that are interpreted as the result of a skill developed influence self-efficacy positively and are likely to lead to confidence in one's ability and future success. Social modelling, on the other hand, occurs when role models (friends, family members, mentors, etc.) succeed at a task. Seeing people successfully complete a task can influence self-efficacy by increasing their belief that they too can possess the skills required to complete said task. Social persuasion can also influence self-efficacy, this time through positive social or verbal feedback while undertaking a task. Finally, physiological arousal includes positive emotional and physical reactions that can facilitate self-efficacy. Negative reactions, such as anxiety or self-doubt, can have the opposite effect and reduce one's belief they can accomplish a task (Bandura, Reference Bandura1977, Reference Bandura1982).

Self-efficacy has been used to understand behaviour change, such as tobacco use and exercise behaviour (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Patrick, Deci and Williams2008; Skarin et al., Reference Skarin, Olsson, Friman and Wästlund2019). Further, some research has explored the role of self-efficacy in travel behaviour change (Crudden et al., Reference Crudden, Anotonelli and O'Mally2016; Skarin et al., Reference Skarin, Olsson, Friman and Wästlund2019). Focusing on a travel behaviour change intervention (i.e. free transit passes), Skarin et al. (Reference Skarin, Olsson, Friman and Wästlund2019) find that both self-efficacy and social support increase an individual's likelihood of achieving travel behaviour change. In Crudden et al. (Reference Crudden, Anotonelli and O'Mally2016), self-efficacy and social problem-solving skills are found to help people who are blind or visually impaired identify and evaluate transportation options and travel arrangements. This paper builds on this research by exploring older adults’ experiences of becoming public transit users through a self-efficacy lens.

Methods

This study took place in Hamilton, Canada, a mid-sized, post-industrial city on the shores of Lake Ontario. Hamilton is served by a municipal transit system (the Hamilton Street Railway (HSR)) and regional transit connecting the city to other urban areas of southern Ontario (GO transit). The focus of this paper is the city's HSR. The HSR comprises a network of buses with an annual ridership of over 20,000 (City of Hamilton, 2020a) and Accessible Transportation Services (ATS) for those unable to access fixed-route public transit (City of Hamilton, 2020b). Seniors aged 65 years or older are eligible for discounted HSR fares and Hamilton residents aged 80 or older can access HSR services for free when they register for a Golden Age Pass (City of Hamilton, 2020b).

This paper draws on a community-engaged study titled Understanding Older Adults Transit Use that was approved by the McMaster Research Ethics Board. Hamilton residents aged 65 years or older who use public transit (defined as having used the city's bus since January 2020 or being registered with the city's ATS) were recruited to take part in this study. Recruitment took place between March and August 2020 and was completed through community organisations’ listservs, posters on the City of Hamilton's official poster kiosks and snowball sampling. Interested older adults were sent an information letter and consent form by email or mail ahead of the interview. Because this research took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, all interviews were done over the phone or online to practise physical distancing. Therefore, oral consent was acquired over the phone or internet call before each interview. Participants were thanked with a Can $20 gift card to a well-known café chain.

While the interviewer had initial concerns about how conducting the interviews over the phone rather than in-person would impact the content and quality of the interview, they were impressed with how comfortable respondents were sharing their experiences, and sometimes painful ones at that, over the telephone. If anything, many respondents expressed how they were eager to share their experiences, and some human connection, through the interview because they felt isolated since lockdowns began. The original research design also included bus-along interviews where the interviewer was meant to join the participants as they prepared for and went on a journey by bus. However, these interviews did not take place due to the public health restrictions in place at the time. We believe valuable insight could have been gained through these mobile interviews and call for future research to do this kind of research, once it is safe to do so.

Though interviews took place during the pandemic, participants were asked to detail both their current and past experiences using public transit and other travel modes. Because this paper presents the results of older adults’ transition to public transit, which occurred in the past for most participants, most of the results presented in this paper reflect the time before lockdowns, concern about virus transmission and reduced travel. A paper presenting older adults’ experiences using public transit during the pandemic has been published elsewhere (Ravensbergen and Newbold, Reference Ravensbergen and Newbold2021). It is, of course, possible that the pandemic influenced participants’ telling of their past experiences, even though the interviewer purposefully designed the interview guide to distinguish current and past experiences on public transport. Further, some participants transitioned to public transport a few years ago, meaning their recall of this time of their lives may not be as accurate as those who more recently transitioned, or were in the process of transitioning, to public transport use.

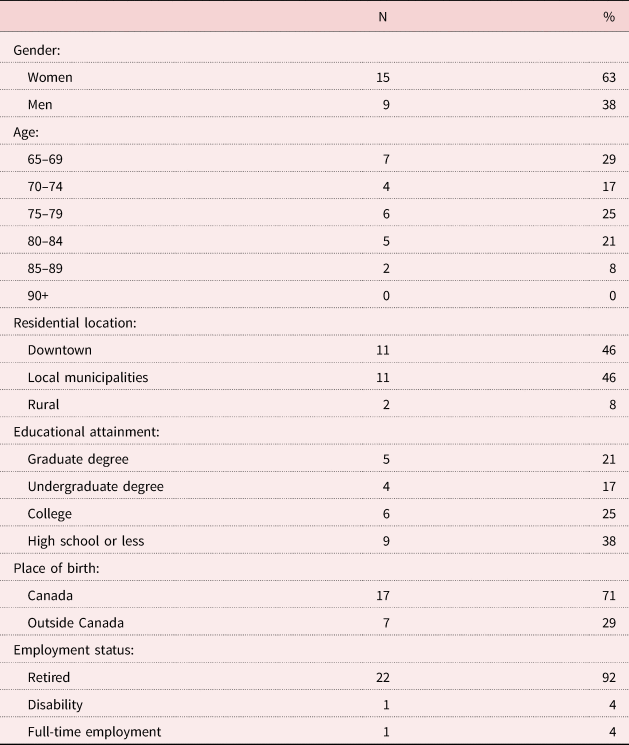

Overall, 32 older adults completed one-on-one semi-structured interviews on their experiences using public transit, 24 of whom used the public bus, the focus of this study. The sample was diverse, through a greater proportion of interviewees were female and retired (Table 1). More than half of the sample (N = 14; 58%) held a valid driver's licence when they were interviewed. Of the ten that did not, only two had never had a licence.

Table 1. Research participant characteristics

The lead author conducted all interviews, which were approximately one hour in length. The interview guide contained two sections. Firstly, participants were asked general demographic and travel questions (10–15 minutes), and then they were asked about their past and current experiences using public transit (45–50 minutes). The second section began by asking older adults to detail their experiences when they first started using public transit. Here, they were probed on when, where and why they started using transit. Participants’ responses to these questions, questions related to travel behaviour change from diverse modes to public transit, are the focus of this paper.

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim in their entirety. The lead author transcribed the first four interviews while the remainder were completed through a professional transcription service. At this point, participants were given pseudonyms to ensure anonymity.

Once all interviews were transcribed, they were systematically and inductively analysed by the lead author using NVivo software. This analysis involves open coding, axial coding and selective coding (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1990; Bryman et al., Reference Bryman, Bell and Teevan2012). First, open coding took place: all transcripts were read line by line and all potential themes were tagged on NVivo. Then, during the axial coding phase, the resultant themes were analysed. Keeping in mind the broader context of the study, some themes were combined while others were divided. During the final phase, selective coding, the key themes, those that came up most frequently or had the most impact, were selected.

During the open coding phase, themes that emerged related to this paper include Past Experience, Sudden Transition, Skill, Confidence and Challenges. During axial coding, these themes were combined, as they all related to the transition towards public transit use. Most of these data comprised interviewees’ responses to the questions about their experiences when they began to use transit. These data were identified as a key theme during selective coding that was named Travel Behaviour Change. All interviews touched on the sub-theme Skill, which led the lead author to explore the literature on skill acquisition. Here, self-efficacy emerged as a framework that helped to explain participants’ experiences. In this paper, case studies from five individuals’ experiences are presented in narrative form and framed with the concept self-efficacy to shed light on the processes shaping travel behaviour change, a gap in the literature identified by Schmitt et al. (Reference Schmitt, Delbosc and Currie2019). The selected case studies represent key informants whose experiences were shared with other respondents; therefore, these narratives are supported by other interviewee quotes throughout.

Results

A clear pattern emerged from the interviews: those who had always travelled using public transit were rarely aware of the sometimes-difficult transition to public transit use some older people experience. For instance, seven interviewees were life-time experienced riders who never had to learn how to use transit as an older adult. These ‘expert’ riders found using public transport easy, for instance Mabel (88 years) shared: ‘I always call myself “The Bus Person” (laughs), I've no other way to get places’; while Olive (66 years) said: ‘But I've always taken the bus, so it doesn't bother me taking a bus.’ These experienced riders were rarely aware of the ways in which transit can be poorly designed to meet their needs as older adults. Those experienced riders who were mindful of the challenges older adults can face accessing transit shared how this awareness was developed through hearing the experiences of other, less-experienced, older adults. For instance, Mike (68), a confident public transit user, shared:

I have no complaints about the HSR … the only thing is learning – and when you talk to people that don't use the buses, that's kind of what they indicate is that, ‘…ah, I never know when it's coming…’, or it's this, or it's that … and sure, I had a little, uh, anxiety … when you first start doing it, you, uh, you figure it out and then; then it's good.

Transitioning to public transit use as an older adult, on the other hand, can require the acquisition of skills. As will be discussed throughout, these skills include trip planning, boarding, knowing where to sit (or where not to sit) and exiting the bus. During the interviews, 16 research participants discussed their experience acquiring these skills when they began using transit, while one was still in the process of learning when they were interviewed. Framed by self-efficacy, we argue that those older adults with experience riding the bus earlier in their lives were more confident in their ability to ride transit while those with less experience had to gain confidence through practice. We explore older adults’ experiences of becoming public transit users in three sections. The first section, ‘Gaining confidence through experience’, presents the story of Emily, the interviewee who was in the process of learning how to use transit as an older adult, to highlight the role confidence plays in influencing travel behaviour change. The second section, ‘Acquiring skills’, presents two narratives: a participant with a smooth transition to public transit use and one who had a difficult transition. Comparing their narratives demonstrates how transition to public transit can be supported by the four factors found to influence self-efficacy. The final section, ‘Ongoing transitions’, expands on current understandings of self-efficacy by highlighting how transitions to public transit use are ongoing. This is done through two narratives, one of a participant who loses confidence through sudden lack of experience, and another who gains it through sudden regular transit use.

Gaining confidence through experience

For older adults with little experience using public transit, a lack of confidence was a major barrier to bus use. For example, take Emily, an 81-year-old participant who lives rurally just outside Hamilton and was in the process of learning how to use transit during the interview. Her travel needs have always been met through driving, something her husband would primarily do. Emily is committed to staying in her farmhouse for as long as possible but is also facing challenges meeting her mobility needs by car now that her husband has passed away and she is partially visually impaired. She has begun regulating her driving by only driving during daylight and to places she is familiar with because: ‘I don't want to lose my licence and ah I need my licence to stay rural. They go together.’

Emily is actively preparing to remain in her rural home with little use of a car. She plans on doing this through a combination of riding the bus, rides with friends and the use of the HSR's ATS. Though she intends on using the bus, she lacks the confidence to do so comfortably, something she shared with her friend, a frequent public transit user:

I said to my friend ‘you know what? I don't think I can get on that bus!’ She said ‘why not? You're able to get on that bus’ and I said ‘I don't feel confident to go on that bus’.

After this exchange, her friend joined her on a bus ride to help her gain confidence: ‘I went down to her place, she met me and then we got on the bus at [names location], that's how I know about that bus.’ This accompanied bus ride helped Emily gain confidence:

When I was on that bus in February, I just said ‘oh my god this is like a king!’ you know, sitting up there. I mean if I was using it all my life I wouldn't feel that way, but I do feel that way.

In fact, it helped so much, she now wants to go on a practice bus ride on her own: ‘So yeah basically what I might do is just get on it and go for a bus ride! (laughs).’

Emily's story highlights the importance of confidence in travel behaviour change. Even though she is keen on using public transit, she did not ‘feel confident’ using it until her friend showed her how to. She directly associates this lack of confidence with her lack of experience: she anticipates needing to ‘go for a bus ride’ to gain that valuable experience and acknowledges that things would be different ‘if I was using it all my life’. This result aligns with self-efficacy: Emily is not confident in her capabilities to use transit successfully because she has too few past accomplishments travelling using transit. She remains optimistic that she will acquire the confidence and skills necessary over time and through experience. In her words:

I mean the anticipation of going to do it … once I've done it two or three times, and that's everything, once I've done it two or three times, I'll be fine.

Acquiring skills

Sixteen research participants transitioned to public transit use as an older adult. All discussed the skills they had to develop to do so confidently and comfortably. Of these 16, 13 described their travel behaviour change as relatively smooth while three found this transition very difficult. This section explores two case studies: Shirley, who experienced a smooth transition to transit use, and Nora, who had a difficult transition. Framed by self-efficacy, we compare their stories to demonstrate how the four factors found to influence self-efficacy, past accomplishments, social modelling, persuasion (social or verbal) and physiological arousal (McAuley and Blissmer, Reference McAuley and Blissmer2000), shape older adults’ transition to public transit.

Shirley's transition to public transport: ‘that's the kind of thing you learn to think about’

Shirley is 81, holds a Golden Age Pass and lives in a suburban area in the upper city of Hamilton. She began using the bus in Hamilton just over a year ago, however, she has past accomplishments using transit: she lived in Europe for most of her adult life where public transportation was her main travel mode. Shirley shared during the interview that her transport needs are currently being met; she can walk to all her necessities, has a car (though she regulates how much she drives) and is generally happy with the bus service, which provides some physiological arousal:

Well for me it's free: number 1. Number 2: Umm, you get to listen to the most interesting conversations, ’cause everybody just talks out loud: especially the young kids ’cause they put the white things in their ear, and they don't realise that they're telling the whole bus! (laughs) … So I always find that kind of amusing, you know?

During her interview, Shirley mentioned many of the skills she had to learn when she transitioned to public transit use, such as getting on and off buses with high steps, riding in crowded buses, navigating snowy/icy sidewalks and bus stops, and getting to her final destination on foot (especially, she shared, when there are limited pedestrian crossings). However, Shirley learned how to overcome these challenges through experience riding the bus. When walking through the steps involved in her travel using the city bus, she began by discussing how she learnt to plan her trips. Here, her granddaughter played a key role by helping her download and use the city's public transit app:

I'm still not great on it, but she put it on my phone so I can look up when the bus is coming … she had to help me quite a bit … it's not all that simple, because you have to press a lot of buttons.

Despite initial challenges learning, Shirley went on to describe regularly using the app when she took the bus.

Other preparations include checking the weather (‘if you need an umbrella, you need an umbrella. If it's snowing, you make sure you have your boots on’), making sure she is not carrying too much (‘you don't want to have to be lugging parcels and stuff, at least I don't, ’cause if the bus gets crowded then where you gonna put the parcel?’), and having her bus pass ready (‘if you keep your bus pass on the outside of your purse you don't really have to do anything because you can just touch that to the screen…’). When asked whether this planning and preparation was difficult, Shirley explained how it has become seamless for her: ‘you kinda learn these things’.

These things Shirley needs to think about and plan for are skills that Shirley has learned through practice. These skills do not stop there, as boarding, riding and exiting the bus require skills as well. In Shirley's word:

…and you get on the bus, you gotta think, that's the kinda thing you learn to think about: So you're going to get on with your right hand (if you're right-handed), and then you need to have your bus pass right ready – ’cause that's the first thing that you do – and then you find a seat. So you just have to kinda make sure that your hand – that's why you can't have a lot of bags – at least I can't; as an older person … getting on, you just get used to it, and also you know, sometimes, like when I first got on the bus, I used to go up the stairs at the back of those buses, and that's not very good for getting off, ’cause then you've gotta really hang on to come down those steps … So I never sit up there anymore, I know exactly where I sit (laughs) you know, you need to be near a pole that you can hold on to, and you can tell the bus to stop when you need to … I've learned … I've learned, ya know.

Gaining the knowledge and skills, as Shirley described, to ride the bus successfully can be a challenge to older adult riders experiencing declining mobility and new to transit ridership. Shirley, however, has overcome these barriers through experience. These initial barriers are things ‘you learn to think about’, things one must ‘get used to’ to become a confident and skilled transit user. For example, Shirley's experiences show how one can learn where to sit through experience, and specifically through bad experiences having trouble getting off the bus when seated near the back.

Shirley's transition to transit use at 80 years old was a success. During the interview she shared how she had decided to give up her car, but then decided not to when the COVID-19 pandemic was declared, and she decided to temporarily avoid transit to reduce her risk of being exposed to the virus. Shirley's experiences of becoming a public transit user highlight the skills required to do so as an older adult. Her story also supports the interdependent relationship between self-efficacy and experience. As she became more experienced, she became more confident and more likely to travel by bus, which in turn gave her even more experience. Further, all four factors found to influence self-efficacy according to McAuley and Blissmer (Reference McAuley and Blissmer2000) influenced Shirley's transition to becoming a transit user: she had past accomplishments using transit regularly when she lived in Europe; her grand-daughter provided social modelling and persuasion; and there is some evidence she experienced physiological arousal, for instance when listening-in on others’ amusing conversations. These four factors were identified in many other respondents’ stories of their transition to public transit use. Past accomplishments, in particular, were regularly found to support older adults’ transition to public transport use. Indeed, of the 13 participants who had a relatively easy time learning to use public transport as an older adult, all but one directly connected their ability to transition to past experience of being a regular transit user earlier in their lives, be it, like Shirley, in Europe (as was the case for two interviewees), in nearby Toronto (the case for three interviewees), or many years ago in Hamilton when they were teenagers or young adults (the case for seven interviewees).

Nora's difficult transition to public transport use: ‘I'm still in transition. I detest it’

Not all older adults’ transition to public transit use was supported, like Shirley's, through past accomplishments, social modelling, persuasion and physiological arousal. For example, take Nora (66), who drove as her primary mode of travel until 2007 when she experienced a serious health problem that made her stop working and resulted in, in her words, ‘immediate poverty’. She explained: ‘I couldn't afford my car, I sold it and then I had to figure out how to ride the bus.’ This ‘figuring out’ was a difficult transition for Nora: ‘I'm still in transition. I detest it.’ Unlike Shirley, who can access many amenities by foot and still owns and drives her car (though she regulates her driving), Nora suddenly had to meet her daily travel needs through transit. She shared how ‘It's overwhelming at the start.’ Unlike Shirley, no one supported her transition to public transit and using transit elicits no physiological arousal: ‘I'm kind of exhausted from riding the bus for almost 14 years, it's like God, I got to do this again?’

Though Nora's transition was challenging, she has still acquired the skills necessary to meet her daily travel needs using transit through experience. She explained how she learnt how to ‘plot your travel’, for instance: ‘If you need groceries, a book, the bank, your medication, you have to think OK how many of this – how much of this is on a straight line, how – because buses are linear.’ Nora has even developed a system to carry everything she needs with her, all the while keeping her hands free, which is especially important for her as she experiences balancing issues:

into my backpack goes the umbrella, the water bottle, you know, the pashmina, the scarf, the little things you buy when you're out and then, you see, when you got it on your back your hands are free.

In line with self-efficacy, Nora has acquired the skills necessary to ride the bus through experience, and this experience has made her more confident. Framed by self-efficacy, her difficult transition to transit use can be understood through a lack of past experience, social modelling, persuasion and physiological arousal. Nora wishes she still had access to a car: ‘It's a very different city when you ride the bus, it's a very different – I'm controlled by the bus.’ Her transition to public transit use, though successful in that she acquired the skills required through experience, was not a choice but a decision forced upon her when she experienced health problems and could no longer afford her car. Nora also did not want to transition to public transit, she would have preferred to continue driving, which may have further contributed to her difficult transition. Unlike Shirley, discussed above, Nora had no choice but to use transit after financial hardship and feels ‘controlled by the bus’. Her difficult transition was shared by two others, who, like Nora, did not regularly use public transit in the past (past accomplishments), nor social modelling or persuasion by friends or family, nor any physiological arousal from travelling by public transport.

Ongoing transitions

Not only does riding the bus require acquiring skills that are developed through experience, but interviewee narratives demonstrate how these skills can also be lost through lack of practice or gained through sudden regular transit use. In this section, two narratives are presented to demonstrate how transitioning to public transport can be a dynamic and ongoing process.

When it comes to losing skills through lack of practice, take Robert, who is 79 and has been using public transit daily since he stopped driving five years ago. This daily travel by bus stopped abruptly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather than this being due to worries about virus transmission on public buses, he shared how this sudden stop was because all his usual destinations were closed, meaning there was nowhere he needs to travel to: ‘I haven't been on the bus since the quarantine went into effect.’ Though normally a frequent and confident bus rider, he shared how this break from public transit has made him lose his confidence:

But I am acquiring an anxiety about getting back on the bus. I'm going to have to make an extra effort to get back into what was a very matter of fact routine … Yeah, I'd be anxious. I will be. But I'll get on. But after a trip or two I will acquire my confidence again.

The COVID-19 pandemic was an event that derailed Robert's mobility routine and reduced his confidence through a temporary lack of experience riding the bus, a break in his usual ‘very matter of fact routine’. A frequent saying amongst older adult participants during the interviews was ‘If you don't use it, you lose it.’ Most said this to justify why they continued to do difficult physical tasks (such as climbing stairs or carrying heavy groceries). Here, Robert's anxieties about getting back on the bus after the pandemic show how riding the bus is also an acquired skill that you can lose if you stop practising the behaviour. Robert's story supports the concept of self-efficacy in that it highlights how riding the bus requires skills, and that these skills can be acquired through practice, or ‘a trip or two’, practice which is needed to ‘acquire [his] confidence again’. It also shows how this process can be dynamic: skills can be gained through practice and be lost through lack of practice.

Events that derail routines can also help older adults gain confidence using public transit. For instance, Don (68) shared how his transition to public transit use was accelerated by a volunteering experience that provided him with free monthly bus passes. Like many others, Don shared how his initial transition had its challenges:

Well it was [challenging] for a little bit but you know trying to find out scheduling and all that. What buses run where and what times. But I gradually got used to it.

Like others, it also took time for Don to gain confidence through experience: ‘[It took] maybe five, six months before I really got the hang of it as to what went where and stuff.’ Unlike many others, however, Don's transition to bus use was helped by a volunteering opportunity that provided him with free monthly transit passes:

It sort of helped then too because I was in this programme … like an 11-month programme. And what they did there you got a monthly pass. HSR pass. ’Cause anywhere we went we had to catch the bus to the person's house. So, I did that for 11 months and that really got me used to what buses went where.

Here, Don's transition to public transit use was supported by an event that provided him with ample experience: ‘I pretty well know where every bus goes now. I've been all over.’ This experience made him a confident public transit user. Taken together, Robert's and Don's experiences highlight how confidence and self-efficacy can be strengthened and diminished through life events.

Discussion and conclusion

In 2009, Sandra Rosenbloom warned: ‘there is no evidence that older people suddenly begin to use public transit upon retirement’ (Rosenbloom, Reference Rosenbloom2009: 33). This paper explores this warning by framing older adult's transition to public transit use with self-efficacy. Results indicate that riding public transit as an older adult can require the acquisition of skills and knowledge such as trip planning, boarding, finding appropriate seating and exiting the bus. Those with little or no experience using transit face a more significant learning curve than those with past accomplishment travelling by transit as they must acquire these skills and gain confidence in their ability to ride transit through practice. Therefore, this paper supports Rosenbloom's (Reference Rosenbloom2009) claim: we cannot assume that all older adults simply ‘become’ transit users once they can no longer drive, even if they live within access to these services. Rather, becoming a transit user can involve a dynamic process of skill acquisition, and many older adults must first gain the confidence required through experience.

In doing so, this paper contributes to the literature on travel behaviour change, and specifically on the research gap identified by Schmitt et al. (Reference Schmitt, Delbosc and Currie2019) on the processes underlying travel behaviour change. This paper also supports the role of self-efficacy in influencing the transition to public transit use. Further, we find some evidence that the four factors identified by McAuley and Blissmer (Reference McAuley and Blissmer2000), namely past accomplishments, e.g. experience using public transit from years ago or from living in another city, social modelling, such as having friends who also use transit, social or verbal persuasion, including encouragement from friends and family, and physiological arousal, such as enjoying travelling by transit, shape self-efficacy. These results are supported by recent research on travel behaviour change that has found that past experience using a travel mode, even in other places, can shape current travel behaviour (Morgan, Reference Morgan2020; Jain et al., Reference Jain, Rose and Johnson2021). We also contribute to this literature by highlighting the ongoing process of self-efficacy: confidence in one's ability to ride transit can be shaped, both positively or negatively, by events such as a pandemic or a volunteer experience involving frequent transit use.

Participants in this study had to have used public transit at least once since January 2020. Therefore, a limitation of this research is that all older adults had either already transitioned to or were in the process of transitioning towards public transit use. Therefore, future work can examine barriers to public transit use amongst older adults who do not currently use transit. This research could determine whether the skills required to use public transit reported herein prevent older adults from changing their travel behaviours altogether. Further, because this research took place over the phone during a global health crisis, participants’ stories may have been influenced by the unique situation in which they were living. Also, the retrospective nature of the stories told may not have been perfectly accurate, especially for those who were sharing experiences that took place years in the past. There is also some evidence that self-efficacy may vary across social characteristics, such as gender (McAuley et al., Reference McAuley, Konopack, Morris, Motl, Hu, Doerksen and Rosengren2006). Participants were not probed during the interviews on how their gender, class, race/ethnicity or other axes of identity may have shaped their transition to public transit use, therefore, future work could explore how these processes vary across axes of social difference.

Results indicate that learning the skills necessary to ride the bus as an older adult can be relatively seamless for those who have past experiences using transit or whose transition to public transit use is supported (e.g. by friends, grandchildren, etc.). This highlights the importance of programmes that provide the opportunity and supports for older adults to try transit. This finding is supported by Shrestha et al. (Reference Shrestha, Millonig, Hounsell and McDonald2017), who stress the importance of older adults becoming familiarised with mobility alternatives to the private car. We agree with Shrestha et al. (Reference Shrestha, Millonig, Hounsell and McDonald2017) that there is a need to develop and implement targeted interventions for those transitioning to public transit in their older years.

Such targeted interventions have taken place in Hamilton. For example, to encourage physical activity levels amongst older adults, the Hamilton Council on Ageing developed the Let's Get Moving programme in 2017, which included a workshop called Let's Take the Bus (WHO, 2020b). This training was part of a three-part series that also included workshops called Let's Take a Walk and Let's Ride a Bike, all of which were facilitated by older adults (WHO, 2020b). Twenty-nine Let's Get Moving workshops attended by 704 older adults took place between 2017 and 2019 (WHO, 2020b). The Let's Take the Bus workshops allowed older adults to try public transit, an experience argued to facilitate the transition to public transit use in this paper. None of the research participants of this study participated in these workshops, therefore, future work can evaluate Let's Take the Bus success in supporting older people's transition to public transit use.

Similar user training programmes have also taken place across cities in Germany and Austria (Marin-Lamellet and Haustein, Reference Marin-Lamellet and Haustein2015). Further, other interventions to aid in older adults’ transition to public transit might include the provision of detailed information targeted for older adults, such as walking distances, number and size of stairs, and presence of elevators and/or ramps (Marin-Lamellet and Haustein, Reference Marin-Lamellet and Haustein2015). Further, programmes that match older adults with someone to accompany them as they make a trip may provide the social support required to gain confidence (Shrestha et al., Reference Shrestha, Millonig, Hounsell and McDonald2017). Pricing incentives are another practice to support older adults’ mobility on transit (Marin-Lamellet and Haustein, Reference Marin-Lamellet and Haustein2015); perhaps further discounting senior fares in Hamilton, e.g. by lowering the eligibility age for the Golden Age Pass (currently set at 80+), to ensure older adults are provided with an incentive to try public transit at a younger age. Transit agencies can also take steps to reduce the physical burden of this transition for older passengers as well. For instance, more accessible bus interiors (e.g. ramps to board, spacious interiors, additional prioritised seating, etc.) may reduce the number of skills required to learn how to use public transport. For instance, skills identified in this study that may be reduced through more accessible design include boarding, finding appropriate seating and exiting the bus.

Of course, public transit is not the only type of mobility that requires the acquisition of skills and the development of confidence through practice or experience. For instance, many participants shared how they regulated their driving because of a lack of confidence in their abilities, often specifically for certain trips or times of day (like Emily and Shirley above). Also, some participants shared how they believed riding the bus kept them active and able to participate more fully in other aspects of social life. Therefore, though we find that using public transit as an older adult can require the acquisition of skills and confidence, we wish to avoid framing public transit as unsuitable for older people. Rather, we argue that easing the transition to transit use for older adults is an important objective in this WHO Decade of Healthy Ageing.

Financial support

This work was supported by the McMaster Institute for Research on Aging.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

This paper draws on a study titled Understanding Older Adults Transit Use that was approved by the McMaster Research Ethics Board.