This essay explores meanings extracted from styles through combining multiple perspectives, some old (design structure, information exchange) and others newer, drawn from visual culture, literary studies, and semiotechnology. This hybrid approach was applied to a small sample of salvage-excavated pottery from modern, heavily populated Flores Island, Guatemala. During the Postclassic (ca. A.D. 1000–1525) and contact (ca. A.D. 1525–1700) periods, Flores was Tayza, capital of the Itza Maya in a conflict-ridden lacustrine landscape. The goal was to untangle relations among style, meaning, and sociopolitical identities through analyzing the spatial distributions of the slipped and decorated ceramics over the island.

Pottery Stylistic Analysis

The study of pottery decorative styles has long basked in the Americanist archaeological and ethnoarchaeological limelight, from the rise of processualism in the 1960s through the early 1990s (see, e.g., Conkey and Hastorf Reference Conkey and Hastorf1990; Hegmon Reference Hegmon1992; Rice Reference Rice2015:392–410). Numerous theories were advanced about styles and their components: what they are, how they are transmitted, and their social meanings. Since then, similar analyses of decorative styles have largely fallen into desuetude, replaced by other concerns (e.g., agency). I propose that certain enduring contributions of the earlier positions can be combined with newer approaches to cultivate a hybrid analytical vigor.

Here, I consider style to be a system of visual expression and communication, distinctive to a particular time, place, group, or individual. Styles are culturally specific combinations of resources, processes, themes, media, and forms. They are at least partly technological—and technology is partly stylistic. Far from being fixed or static, styles are open and dynamic, and they change as relevant new information—social, religious, political, or other—enters the cultural system.

Early Approaches: Design Structure and Information Exchange

Hierarchical design-structure analysis (HDSA), as applied ethnographically to pottery decoration, focuses on the potter's sequential decisions involved in embellishing a vessel (Friedrich Reference Friedrich1970). It begins with identifying the distinct spaces of the decorated vessel's surface: the layout that establishes the design field(s), which may be formally demarcated by boundary markers or framing lines. Analysis then focuses on decisions that determined the location of decorations. The smallest component in HDSA is a design element, which may be a single stroke of a paint-brush or an incising/impressing tool. Elements are combined into more complex patterns or arrangements called motifs or configurations, placed within the defined fields. This step-wise sequence, with early decisions affecting later ones, establishes the hierarchy of the design structure, that is, its rules or logic. In this approach, a dialectic can be seen between agency (choice of design components) and structure (overall style; Hegmon and Kulow Reference Hegmon and Kulow2005).

In 1977 Marvin Wobst published an influential essay about how styles communicate in what has come to be known as stylistic messaging or information-exchange theory. He offered numerous propositions about the information incorporated into styles and symbols and its communication, based on visibility and the social and physical distance between the sender and receiver. For example, he suggested that (1) the intensity of stylistic behavior should correlate positively with the size of social networks (Wobst Reference Wobst and Cleland1977:326). It follows, then, that (2) a positive relationship exists among the visibility or ease of recognition of a style or symbol, the size of the geographic area of its distribution, and the size of the group being identified (Wobst Reference Wobst and Cleland1977:330, 335). Similarly, (3) artifacts are more likely to carry stylistic messages if they are potentially visible to large numbers of people, rather than only within a household (Wobst Reference Wobst and Cleland1977:328–329). (4) Objects with a relatively restricted distribution and low visibility will express themes of local specificity (Wobst Reference Wobst and Cleland1977:335). And (5), in times of social, demographic, or economic stress and competition, information exchange through stylistic messaging will manifest as group-specific or regionalized styles. Variability within these styles signals group affiliation, highlights elites, and enhances boundary maintenance (Wobst Reference Wobst and Cleland1977:329, 332–333; see also Hodder Reference Hodder1979:447–450; Plog Reference Plog1980:129–139).

A long-standing argument about pottery decorative styles concerned whether their communicative role was active or passive. One position viewed decoration as consciously and actively chosen to convey messages of identity and boundary identification and maintenance (e.g., Bowser Reference Bowser2000; Hegmon Reference Hegmon1992; Hodder Reference Hodder1977; Weissner Reference Weissner1983). Alternatively, styles can be seen as passive, unconscious repetitions of customary behaviors and designs: “isochrestic” (Sackett Reference Sackett1985) like Pierre Bourdieu's (Reference Bourdieu1977) habitus.

With respect to Petén Postclassic pottery, it is difficult to know if the motifs had the same meanings throughout the lakes region or how they survived disjunctions over time and space (see Kubler Reference Kubler and Lothrop1961), given that some can be found in Classic times (A.D. 200–900/1000). Moreover, meanings are constructed from experience, and to communicate effectively these meanings should be decodable by both sender (artisan) and vessel viewer/user through shared experience. The absence of intersubjectivity—shared experiences among Postclassic Maya and twenty-first-century academicians—obliges us to explore other approaches to interpreting meaning in visual culture.

Some Newer Approaches: Investigating Meaning

More recent approaches to style continue to focus on its communicative role, but with greater emphasis on how its messages or meanings are constructed by an audience of viewers. The communicative function of objects, motifs, and symbols is semasiographic: meanings are conveyed visually by signs and images rather than by written or spoken words and their semantic values.

One subset of the relatively new field of visual culture studies (or visual studies) concerns visual rhetoric as an analogue to verbal rhetoric: how “visual elements are used to influence people's attitudes, opinions, and beliefs” (Helmers and Hill Reference Helmers, Hill, Hill and Helmers2004:2). With reference to pottery, the interest is in how images and symbols, such as forms and decoration, communicate meaning to an audience and how the audience formulates these meanings (Foss Reference Foss, Hill and Helmers2004:306). Analysis addresses the “nature” of an artifact and its distinguishing features, which may be presented or suggested. Presented features or elements include overt visual characteristics such as medium, color, texture, and so on. Suggested elements are the “concepts, ideas, themes, and allusions that a viewer is likely to infer from the presented elements,” that is, their messages or meanings (Foss Reference Foss, Hill and Helmers2004:307). Much like Bruno Latour's (Reference Latour2005) concept of object agency in constructing the social, visual studies engage a dialectic involving “the social construction of the visual field [and] the visual construction of the social field” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2002:170–171). For archaeologists, the rhetorical focus subsumes the objects and symbols that affected past lives in a broad range of human experiences, echoing habitus (see Foss Reference Foss, Hill and Helmers2004:303).

Another way to consider meaning is through the concept of an interpretive community. The meaning of a work of art, or a text, or a set of icons, symbols, or motifs, is partly that intended by the creator/artist but also that of the viewer or reader. With reference to texts, the reader-response school of literary theory is concerned with the reader's reaction to, and creation of, the meaning of a literary work as distinct from that of the author. Similarly, visual rhetoric scholars do not see the intentions of an artifact's creator as determining its correct interpretation (Foss Reference Foss, Hill and Helmers2004:308). Literary theorist Stanley Fish (Reference Fish1976, Reference Fish and Fish1980:171), through a critical reading of the Variorum Commentary on Milton's poems, invented the concept of an interpretive community, whose members share the same epistemology or set of “interpretive strategies . . . for constituting [a text's] properties and assigning their intentions.” Much as with the shared “doing” or praxis through interactions in communities of practice (Lave and Wenger Reference Lave and Wenger1991), these interpretive strategies are culturally constructed and learned (in part through language sharing and also through academic training), based on generally subjective assumptions about what things (words, texts, icons, motifs) mean and how they should be interpreted. Elsewhere, Fish has explained these communities in terms of members sharing “a point of view or way of organizing experience . . . [and] distinctions, categories of understanding, and stipulations of relevance and irrelevance” (Fish Reference Fish1989:141, quoted in Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:98).

Still another way of approaching meaning comes from the concept of semiotechnology, employed in recent studies of systems of communication through modern social media. The term refers to analyses of technocultural assemblages that combine the ideas of semiotics (the science of signification—how signs convey meaning; see Bauer Reference Bauer2002) with studies of modern communications technology. Many studies build on debates concerning how the meanings of signs—written words and fixed significations—can be distorted in these media in comparison to face-to-face verbal communication, where much of the message is conveyed not only by words themselves but by body language.Footnote 1 A recent exploration of semiotechnology by Ganaele Langlois (Reference Langlois2011, Reference Langlois2014) confronts this debate from the viewpoint of meaning and “making sense” of the world. Meanings of things and events are both individually and collectively (culturally) constructed paths by which we decipher the known and unknown and situate ourselves within. These pathways are constructed by often unseen “power formations that mobilize language, signification, [and] representational and informational technologies” (Langlois Reference Langlois2011:2). The making of meanings is an everyday task, but also a complex exercise that simultaneously empowers, emancipates, and subjugates (Langlois Reference Langlois2014). Meaning is not simply signification per se but instead, with respect to technology, can be thought of as a liminal space where “the transition from signification to making sense” unfolds (Langlois Reference Langlois2014). Semiotechnologies “can serve to organize a reality, or a set of common expectations, and therefore maintain, or challenge, relations of power” (Langlois Reference Langlois2011:11).

The semiotechnologies of the early twenty-first century—online communications technologies, participatory media, Facebook, Google, various proprietary software, Wikipedia, and so on—are generally commercialized, and are often manipulative or invasive, mechanical ways of producing signs and meanings from data that can be collected and used in targeted advertisements, or in surveillance or other ethically questionable platforms (Langlois Reference Langlois2014). Traditional or “older media forms,” by contrast, were primarily designed to communicate meanings through construction of both signs and practices of making sense of the world. The focus of semiotechnology studies, then, should be less on signification and more on the “regimes of production and circulation of meaning” (Langlois Reference Langlois2011:1).

What do these new pathways to the study of objects and symbols—visual rhetoric, interpretive communities, and semiotechnology—add to older ones (information exchange, design-structure analysis)? How can they contribute to understanding the meanings of Petén Postclassic pottery decoration? First, Postclassic settlements can be considered interpretive communities with shared categories of understanding concerning the visual objects and symbols in the daily lives of people. Second, the pottery forms, layouts, colors, and motifs constitute power-laden rhetorical devices and a vocabulary for communication. Third, Postclassic pottery style and decoration can be considered a kind of “older media form” of semiotechnology: pottery is a technology, and its decoration consists of signs or icons (motifs). Pottery as a semiotechnology can be studied from the viewpoint of material culture having agency, à la actor-network theory (Latour Reference Latour2005), in constructing the social. Thus decorated pottery helped the Postclassic- and contact-period Itzas, and their rivals the Kowojs, make sense of their world and its changing power relations, because the decoration had meanings (sometimes semantic) and agential force. The key, then, is to decode the visual rhetoric—the “concepts, ideas, themes, and allusions”—mobilized and deployed in the styles, layouts, and motifs.

Background: The Central Petén Postclassic

The lakes region of the Department of Petén, northern Guatemala, is defined by an east-west line of lakes formed along a fault line at approximately 17° north latitude. These bodies of water, from west to east, are Sacpuy, Petén Itzá (the largest), with tiny Petenxil and Quexil to the south, Salpetén, Macanché, Yaxhá, and Sacnab (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of the central Petén lakes, showing the territories of the Itzas, Chakʹan Itzas, and Kowojs, and sites mentioned in the text.

Itzas, Kowojs, and Their Factions

My nearly 40-year interest in the Postclassic- and contact-period ceramics of this area began with perplexity at the pronounced differences, particularly in pastes and decoration, between the pottery from the Topoxté Islands in Lake Yaxhá in the east (Bullard Reference Bullard and Bullard1970; Rice Reference Rice1979) and that around Lake Petén Itzá in the west (Chase Reference Chase and Chase1983; Cowgill Reference Cowgill1963). The sites of these lake basins were further differentiated by the presence of distinctive temple assemblage architecture in the east, which was absent in the west (Rice Reference Rice, Sabloff and Wyllys1986). Grant Jones's (Reference Jones1998) archival studies partly clarified the situation. Two feuding “ethnopolities” occupied opposite ends of the lake chain—the powerful Itza confederacy in the Lake Petén Itzá basin and the Kowojs in the Yaxhá basin, with settlements on the Topoxté Islands. The reality was, of course, more complex, with factional divisions within each polity.

Archaeological research on the Topoxté Islands indicated they were largely abandoned around A.D. 1450–1475 (Wurster and Hermes Reference Wurster, Hermes and Wurster2000:249). It is likely that the inhabitants departed in two factions. One apparently settled one day's travel north of Lake Petén Itzá (Atran et al. Reference Atran, Lois and Ucan Ekʹ2004:6; Jones Reference Jones1998:280), perhaps at the Tikal ruins. Another faction, better known historically and archaeologically, began aggressively moving westward, usurping former Itza territory, establishing a center at Zacpeten in Lake Salpetén and constructing two of their signature architectural temple assemblages there (Pugh Reference Pugh2001, Reference Pugh2003, Reference Pugh, Rice and Rice2009). By the late seventeenth century, this expansionist group had taken over the Itza port town of Ixlu on the narrow isthmus separating Lakes Salpetén and Petén Itzá, where they built another temple assemblage (Rice and Rice Reference Rice and Rice2016) and established settlements over much of the northern shore of the latter.

Among the late seventeenth-century Itzas, the ruling group was led by the Ajaw Kan Ekʹ, who lived, along with his relatives, in the capital known variously as Tayza or Nojpeten (modern Flores Island), in the southern basin of Lake Petén Itzá. But the Ajaw's leadership was strongly contested by the Chakʹan Itza faction, who occupied the western mainland area of Lake Petén Itzá and Lake Sacpuy, and who had entered into alliance with the Kowojs against Kan Ekʹ.

Postconquest, both the Itzas and Kowojs told the Spaniards of ties to the northern Yucatán Peninsula (Jones Reference Jones1998). The Petén Itzas claimed family and lands at Chichen Itza, in eastern Itza territory. The Kowojs told the Spaniards that they had recently left Mayapan, and I consider them to be a lineage involved in the western Xiw alliance (Rice and Rice Reference Rice and Rice2009). Although the northern Itzas and Xiws had jointly governed Mayapan, their relationship was strained. Political disruptions prompted repeated southward migrations of members of both groups to join kin in the heavily forested and isolated lakes region. In Petén, Late Postclassic conflicts, perhaps related to those plaguing the north, accelerated factionalism. By the end of the seventeenth century these hostilities—exacerbated by sharp disagreements about how to respond to the Spanish invaders’ demands for capitulation to the Spanish crown and conversion to Christianity—had escalated to civil war, with the Kowojs burning a part of Tayza (Jones Reference Jones1998:326, 444n33, 497n12).

For archaeologists investigating communities or factions within them that are embroiled in such contested circumstances, it is difficult to materially distinguish the participants, their collective identities, their physical locations, their strategies for asserting power and instituting resistance, and more. I wondered if decorated pottery styles might shed light on these complex ethnopolitical identities at Tayza.

Pottery Styles and Components

Although Kowoj pottery has been widely studied (Bullard Reference Bullard and Bullard1970; Cecil Reference Cecil2001; Hermes Reference Hermes and Wurster2000; Rice Reference Rice1979; Rice and Cecil Reference Rice, Cecil, Rice and Rice2009), that of the Itzas has received far less attention; the scholarship that exists is generally old, superficial, unpublished, or in venues with limited circulation (e.g., Berlin Reference Berlin1955; Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1983; Cowgill Reference Cowgill1963; Forsyth Reference Forsyth1996; Gámez Reference Gámez, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2007; Hansen Reference Hansen1997; Romero et al. Reference Romero, Luís, Ramírez Baldizon and Castellanos1999; Soto Reference Pérez and Marina2006). Recent fieldwork in Itza territory indicates that the Kowoj and Itza polities deployed similar but distinct pottery decorative styles. The most useful criteria for differentiating them are the “presented” components of their rhetoric (Foss Reference Foss, Hill and Helmers2004:307): design structure or layout, colors, and motifs. Thus, although the decorated pottery of both was red-slipped, the two can be distinguished on multiple criteria, beginning with paste ware. Itza potters produced tan-gray, silty, Snail-Inclusion Paste (hereafter SIP) ware; the Kowojs made marly Clemencia Cream Paste (CCP) ware (see Cecil Reference Cecil2001, Reference Cecil, Rice and Rice2009a).

With respect to layout, potters and pottery decorators in both Itza and Kowoj settlements shared a template for how and where to apply decoration: in bands. This is evidence of a single community of interpretation and practice. The decorative field, framed by two lines above and one or two below, encircled the interior wall of shallow bowls and tripod dishes, and the exterior of forms with restricted orifices (Figure 2a, 2b). The band might be quadripartitioned, formally by vertical lines or informally by the positioning of isolated motifs. This simple structure was widespread, typically painted (Itzas black; Kowojs red), and less commonly incised.

Figure 2. Layouts of decorated Petén Postclassic pottery: a) banded and quadripartite paneled, b) banded and informally quadripartitioned, c) distributive.

In the Late Postclassic the Kowojs initiated a new, ethno-specific, non-banded “distributive” layout on their CCP ware (Figure 2c). This arrangement featured two circumferential lines above curvilinear, dotted, red-painted decoration covering the entire interior of tripod dishes (Hermes Reference Hermes and Wurster2000; Rice Reference Rice1979). The Itzas later adopted this horror vacui style on their SIP dishes, primarily Macanché Red-on-paste: Macanché variety, but also Sacá Polychrome.

Color “was a central element of ancient Maya experience, crucial to the making of meaning and identity” (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Brittenham, Mesick, Tokovinine and Warinner2009:69), and thus it likely established some of the “themes and allusions” (Foss Reference Foss, Hill and Helmers2004:307) of the visual rhetoric of the pottery. The Maya observed deep and long-standing cosmological color senses, particularly directional associations tracking the path of the sun and the order of ritual circuits (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Brittenham, Mesick, Tokovinine and Warinner2009:27–40). Red (chak) is associated with east and sunrise; extensional meanings include hot and great. White (sak), associated with north and up (sun at zenith), has secondary meanings of pale, artificial, and beautiful. Black (ekʹ), aligned with west (setting sun), has generally negative extensions to darkness and restricted vision. Yellow (kʹan) represents south or down, the night sun traversing the Underworld from west to east; secondary meanings include ripe, mature, and precious. A fifth direction, center, was yax, blue, green, or blue-green; senses include fresh, new, first, and precious.

With respect to Maya pottery, various shades of red and black were the most common paint colors. These, plus a light, creamy background, represent a “high-contrast triad” having lasting associations with function and meaning (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Brittenham, Mesick, Tokovinine and Warinner2009:72). Colors used to decorate pottery may also correspond to body painting (Cecil Reference Cecil, Cecil and Pugh2009b:244). In 1696, the allied Kowojs and Chakʹan Itzas reportedly came to Tayza wearing red body paint and black face paint. The faces of Itza men also were scarified (“incised”; Avendaño Reference Fray and Comparato1987:38, 48, 51 [1696]). Compositional analyses revealed that Kowojs and Itzas used different sources for the red and black pigments painted on different pottery types (Cecil and Neff Reference Cecil and Neff2006; see also Pugh and Cecil Reference Pugh and Cecil2012).

Pottery and body paint colors and directional symbolism might be ethnopolitically specific. Kowoj territory was in the eastern lakes, expanding north and westward in the Late Postclassic; their pottery was red (east) on white (north). Itza territory was in the west (black) and south (yellow) of the lakes region and their pottery was painted black. Yellow colors were not used by either group. The background color of some Itza black-painted banded decoration was occasionally a pale yellow-orange, but this was not used consistently. Incense burners and slipped vessels among both Kowojs and Itzas sometimes featured a post-fire coating of Maya Blue.Footnote 2 This yax pigment signified some aspect or function of the vessel as fresh or precious, and conferred sacrality.

Tayza, the Island Capital of the Itza

Although Tayza was also known as noj peten, “big island,” Flores is actually small, covering only 9.6 ha (23.7 acres), its elevated center rising ~17 m above the ever-fluctuating lake level. The premodern occupations of the island are completely entombed by densely packed residences, commercial buildings, and tourist facilities along paved streets. Consequently, space for systematic archaeological excavation is extremely scarce.

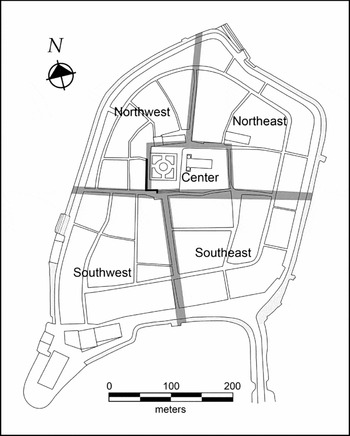

We will never get a detailed picture of what Tayza looked like before conquest, but some hints come from the writings of Spanish missionaries and military men. The town was noted for its white appearance—stuccoed limestone structures—and its elevated center was, then as now, its politico-religious core. Three “temples” stood there, one of which had nine tiers resembling the Kukulcan temples of Chichen Itza and Mayapan. The Spaniards were told that the island had four named barrios (Jones Reference Jones1998:84, 99–100) and indeed, Flores's major streets, descending from the plaza, divide the island into unequal quadrants that may be vestiges of the Itza settlement (Figure 3). At the same time, two circumferential thoroughfares, inner and outer, support the notion of concentric patterning. A key question concerns the location of the residence and temple of the Ajaw Kan Ekʹ, reportedly a short distance from one of the many canoe landing places on the island.

Figure 3. Map of Flores Island, showing the four quadrants and center.

Pottery at Tayza: General Observations

Between 2004 and 2014, during brief visits to Flores for other purposes, I was occasionally able to examine bags of pottery recovered in excavations associated with various public-works projects; these were accessible in local lab facilities and private pottery collections. I was interested in the relations between pottery and ethnopolitical identities. I began with Spanish observations that members of the Itza governing council—leaders of the four cardinally oriented provinces of Itza territory and other nobility, including the ruler Ajaw Kan Ekʹ himself—resided in their respective quadrants of the island (Jones Reference Jones1998:60–61, 71). Was the social pluralism of Late Postclassic- and contact-period Petén reflected in the abundant decorated pottery recovered at Tayza/Flores—for example, in the spatial disposition of motifs?

Attempting to answer that question proved exceedingly—indeed, laughably—ambitious for several reasons. Although decorated pottery was common on the noj peten, it was unclear how the town was organized spatially. Representative spatial sampling and excavation controls (other than coarse-grained horizontal provenience data) were absent in the recovery of much of the Flores rescate material.Footnote 3 Moreover, research at Late Postclassic Mayapan in northern Yucatán failed to identify any “clear distinctions among household pottery assemblages” that might relate to the ethnopolitical identities of resident members of the League confederacy (Masson and Peraza Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014:6). There, decorated serving wares occurred in low frequencies and were not concentrated in elite contexts.

Given these circumstances, I reoriented my focus to a more open-ended inquiry exploring differences in spatial disposition of decorated Postclassic pottery types, varieties, forms, layouts, styles, and motifs over the island (Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2017a). I also compared these with evidence from mainland sites. I was interested in the visual culture aspects of the pottery: what styles did and “said,” and how they held meanings for the makers and users.

In general, I found that vessels of almost all forms and types recovered on Flores Island were larger than those from other lacustrine sites and showed a greater range in sizes, from very large to miniatures. Unslipped pottery and incensario fragments, particularly composite types, occurred in virtually all excavations. Comal rims were occasionally noted. Globular ollas were used for urn burials of infants and children. Most of the slipped and decorated pottery was SIP ware, primarily types in the Paxcamán ceramic group. Trapeche group pottery was present, mostly in the north and west sectors, but generally uncommon. Augustine Red fragments occurred unevenly, found primarily around the perimeter roads. The most common forms were large monochrome jars and grater bowls, suggesting utilitarian (rather than serving) functions, perhaps in kitchens; drums were also common. Only two polychrome-decorated Augustine group sherds were noted (Figure 5d). Imports included small quantities of Yucatán types (Mama Red, Chichen Red, Tacopate Trickle, and slate wares) on the island and also at mainland sites, plus scarce Fine Orange and rare Plumbate. Spanish imports are extremely rare throughout the lakes district, and tin-enameled wares (majolica) at Tayasal were primarily products of colonial Antigua.

Decorated Pottery at Tayza

I pursued spatial analysis of the decorated pottery fragments of Flores Island by sector or quadrant. Regardless of whether the claim that the Itzas’ noj peten was organized around four barrios is empirically true, intercardinal quadrants can be distinguished by modern streets: northeast, northwest, southwest, and southeast, plus the center, the civic-ceremonial core (Figure 3). Sometimes, because of unclear provenience data, I categorized locations simply as north, center, or south.

Forms and Types

Decorated vessels were primarily for food or beverage service and were categorized by form as bowl (simple, collared, other), tripod dish or plate, jar, tecomate (neck-less globular jar), or miniature. Tripod dishes were the most common decorated form everywhere on the island (37 percent), especially in the southeastern quadrant, followed by bowls and collared bowls (31.7 percent), the latter particularly noted in the center of the island. The major types and varieties of decorated wares are tabulated in Table 1. Most sherds were Paxcamán-group types, including Ixpop (black-painted decoration), Sacá (red-and-black), Tachis variety of Macanché Red-on-paste (geometric motifs), and fine-line Picú Incised.

Table 1. Frequencies of Decorated Pottery of the SIP-Ware Paxcamán Ceramic Group and Other Wares at Flores, by Sector.

a “Other” refers to Postclassic decorated materials other than the Paxcamán group, and includes rare sherds of the Trapeche ceramic group (SIP ware) and VOR, CCP, and Fine Orange wares.

Motifs and Icons

Technically, the terms motif and icon have different senses: a motif is a decorative or ornamental design or the pattern created by that design; an icon is an image of something (often religious) that has meaning(s), which are frequently semantic. Icons are motifs with significant symbolic loading. Both may be symbols or pictograms—that is, exhibiting similarity between form and meaning (iconicity). Complex decorative arrangements (of motifs and layouts) may be considered symbolic codes.

Postclassic Maya decorated pottery displayed numerous motifs and icons, some of which are localized and regionalized expressions of the Postclassic International style and symbol set, also seen in murals (Boone and Smith Reference Boone, Smith, Smith and Berdan2003). Others are drawn from a durable lowland repertoire and some also appeared on earlier Classic polychromes. The motifs on the Tayza pottery are grouped into four categories: glyphs, geometric, naturalistic, and abstract-cursive (see Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2017a).

Glyphs include glyph-like elements, and comprise day signs (e.g., Ajaw), solar and lunar disks, Venus/star symbols, and curls, hooks, and volutes that may relate to flowers or feathers (Figure 4a). They typically appear in banded and paneled layouts. The “supernatural eye” icon, also known as the God M (god of trade) name glyph, consists of a scrolled U-shape with a circle (the pupil) in the interior loop. Widely distributed in Mesoamerica and resembling Zapotec Glyph C, it pertains to deities, serpents, and Venus/stars. The RE or reptile-eye glyph is a left-facing profiled head showing an eye and topped with a curled feather or crest (Figure 4c). A well-known day sign in highland Mexico, the RE icon typically appears on Ixpop Polychrome vessels on Flores and elsewhere. The woven mat (pop), a distinctive icon of Maya royal regalia since Classic times (Robiscek Reference Robiscek1975), is also a “month” name and symbol of the seat of power. Rare in the International/Mixteca-Puebla symbol set, mats and related twists and knots typically occur in quadripartite banded decoration, painted or incised, and frequently as separators or boundary markers (Figure 4d–f).

Figure 4. Decorative motifs in bands (island sector): a) feathers, Picú Incised collared bowl rim (center); b) Ajaw face between feathers(?), Ixpop Polychrome (center); c) RE glyph, Ixpop Polychrome tripod dish (eye eroded; no provenience); Picú Incised mat motifs on collared bowls, d) with traces of blue pigment (north); e) (southeast); angular motifs, f) triangles over twist over reptilian with supernatural eye, Picú Incised collared bowl (Tayasal Peninsula); g) step-fret, Ixpop Polychrome jar shoulder (northwest).

Geometric motifs may be angular or rounded. Angular motifs typically but not invariably occur in bands; they may be painted red or black or incised. Rounded motifs—circles, ovoids, U-shapes—may be plain, concentric, or embellished with dots (Figure 5a, b), and may represent water, eyes, jade, or vegetal elements.

Figure 5. Decorative motifs in bands (island sector): round motifs, a) nested circles with crosshatching, Ixpop Polychrome bowl (southwest); b) dotted circle, Ixpop Polychrome (southwest); c) abstract-cursive, Saca Polychrome tripod dish (southwest); d) Graciela Polychrome (northwest); e) double bands, Ixpop Polychrome dish (northwest).

Naturalistic motifs include snakes, reptiles, birds, humans, and vegetation (Figure 6a, b). Snakes and reptiles, often indistinguishable and frequently part of composite creatures that include avian elements, such as beaks or feathers, are relatively common. They are likely local or regional variants of the supernatural feathered serpent from the International painting style. Birds are shown as profile heads with large curving beaks, suggesting raptors, parrots, macaws, or the curassow.Footnote 4 Feathery elements frequently accompany all these creatures. Humans, body parts, and varied animals are well-known in the International style but rare on Petén pottery.

Figure 6. Decorative motifs (island sector): a) distributive style with supernatural eye in bird head, Macanché Red-on-paste, Macanché variety tripod dish (southeast); b) naturalistic motif, composite avian-reptile with feathers below, Sacá Polychrome basin (center); c) abstract-cursive, plaque, Sacá Polychrome lid (southeast).

Abstract-cursive motifs, difficult to characterize, are primarily ornate, curvilinear elements similar to those of the distributive style but occurring in isolation or as embellishments of rectangular “plaques” (Figures 5c, 6c). Some may be feathers or vegetation. Generally uncommon, they tend to appear in Sacá Polychrome-type pottery.

Spatial Distributions

It is here that the findings of this project become most tenuous because of small and non-probabilistic samples (see note 3), making statistical analysis inappropriate. Most motifs were distributed throughout the island, albeit in low frequencies, but some gross generalizations about quadrants can be put forward, especially in concert with other information (Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2017a, Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2017b).

The ceremonial core of the island, its elevated center, yielded common Ixpop Polychrome and Picú Incised types. Incising often features feathers as primary or secondary motifs, or triangles and twists in encircling bands (Table 2; Figure 4f). Two examples of an unusual, heavily decorated Picú chalice form with a pedestal base came from the center, along with common effigy censer fragments.

Table 2. Frequency of Nine Motifs at Flores, by Sector.

a RE is reptile eye glyph.

b The bird head with a “supernatural eye” is counted twice.

In the north, pottery decoration seemed to emphasize black-painted Ixpop Polychrome with reptile motifs, including the RE glyph. Sacá Polychrome and Macanché Red-on-paste were rare. Two molds for forming effigy censer faces were found in the northwest quadrant, which also yielded more pottery and more elaborate decoration than the northeast (e.g., Figure 5e), although this might be a consequence of minimal sampling of the latter. An excavation at the extreme northern edge of the island recovered abundant fauna, several chert points, and a broken grinding stone fragment used as a pounder, suggesting the area was involved in cooking or butchering.

Beautifully painted Sacá Polychrome and its varieties are common in the southern part of the island, with unusual forms including dome-shaped lids (Figure 6c) and flaring-sided basins (Figure 6b), often decorated on both interior and exterior surfaces. Some Sacá vessels displayed the distributive style of decoration characteristic of the Kowoj CCP ware, but with motifs painted red rather than black. Mats and twists are slightly more evident in the south.

The southeast quadrant is comparable to the ceremonial center in terms of high frequencies of types and variety of motifs (e.g., Ajaw, birds), but the southeast yielded a greater variety of forms. Sacá Polychrome and other decorated wares were particularly common in the southeast, along with Macanché Red-on-paste and unusual SIP sherds dubbed “Petén Plomizo.” Motifs include feathers, plaques, and mats, and the supernatural eye appears in the profile head of a large-beaked bird on a Macanché Red-on-paste tripod dish (Figure 6a). A few fragments of Augustine Red, Kowoj CCP ware, and effigy and composite censers were found, plus other stuccoed and painted wares. Imports included Fine Orange, Chichen Red, Plumbate, and a replica of a Mixtec-style openwork censer made of “local” (presumably SIP) paste (Chase Reference Chase and Chase1983:1221, Figures 4–13).

Public-works excavations near the center of the southeast quadrant revealed the edge of a masonry platform with a talud-like wall, a large sculptured stone serpent head, stuccoed and painted red, and the legs of an exceptionally large effigy censer.Footnote 5 A private collection from a construction site near this area included sherds of large Sacá and other vessels. Fragments of eight or nine SIP tripod dishes were possibly paired by type: Ixpop, Sacá, and Macanché Red-on-paste (Macanché and Ivo varieties).

All these data—platform, serpent head, censers, paired dishes, nonlocal pottery—support the likelihood that influential structures and activities existed in the southeast area of Tayza. We believe this quadrant was the location of the residence and personal temple of the Itza ruler, the Ajaw Kan Ekʹ. A visiting Spanish priest described the residence in 1696 as a “tandem” or two-room, open-hall structure, probably also serving as a council house (popol nah). The Ajaw Kan Ekʹ received guests in the front room or vestibule, where there were 12 seats around a masonry “table” (Avendaño Reference Fray and Comparato1987:34 [1696]). The abundance of highly decorated pottery in this area is consonant with these royal functions.

What Do Itza Pottery Styles and Motifs Mean?

Despite the limitations of the sample, this overview of spatial variability in slipped and decorated Postclassic pottery on Flores Island provides hints of the social and functional differentiation of the poorly understood Petén Itza capital. I suggest that the southeast was occupied by royal elites, the southwest probably by non-royal nobles, and the north by persons of lesser status. The center was primarily civic-ceremonial. The most elaborate decoration, such as variants of Sacá Polychrome with innovative layouts and color use or Macanché Red-on-paste, was primarily seen in the south, but no specific motifs predominated. The painted pottery in the center and northern sectors appears to emphasize traditional black, banded Ixpop Polychrome with reptile and feather motifs, all of which were less common in the collections I reviewed from the south.

The SIP types and decoration seen in the northern part of Tayza are similar to those of the pottery recovered at mainland sites in the Lake Petén Itzá basin (Table 3). The dearth of decorated pottery at mainland sites, first noted by George Cowgill (Reference Cowgill1963:43, Tables 5 and 6), was also observed in more recent excavations at Ixlu in the east (Rice and Rice Reference Rice and Rice2016:81), at Nixtun-Chʹich' in the west (Chakʹan Itza territory), and on the islands in Lake Quexil (see Shiratori et al. Reference Shiratori, Zetina, Salas, Soto, Arroyo, Paiz, Linares and Arroyave2011). Throughout this area, decoration on black-painted Ixpop Polychrome and the rare Pek Polychrome (Augustine group) favored symbolically loaded reptilian icons (Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1983:Figure 25b; Rice Reference Rice1987:Figures 43, 44a–c) or more neutral motifs such as glyph-like elements. The complex design structures and motifs of Sacá Polychrome variants seen on the island, for example, are lacking. This differential occurrence may be explained by Wobst's proposals about stylistic messaging; the widespread reptile imagery illustrates his proposition that easily recognized symbols carry information that identifies large groups over large areas.

Table 3. Frequencies of Five Types of Decorated Pottery at Sites around Lakes Petén Itzá and Sacpuy.

Note: Cowgill Reference Cowgill1963:Tables 5, 6. Figures are “after mending” totals and include his “near [type]” figures.

But what explains the differential occurrence of decorative types and motifs between northern and southern sectors of Tayza? One easy answer is economic: Ixpop Polychrome and Augustine Red monochrome vessels might have been less “costly” (in resources or producer time) than multicolor painted or fine-incised pots. The latter would have been less accessible to the lower-status populations in the north of the island (and those on the mainland, who may also have been of lower status). Or, perhaps the highly decorated ware was specifically denied to non-nobles. Or, the producers of the fancy vessels used by elites and in temple ritual may have been so-called attached specialists, enjoying the patronage of the Itza royals. Again, Wobst's propositions are relevant: intense stylistic messaging correlates with larger social networks among the elite and broad visibility outside the household (particularly around the Ajaw's residence).

Further insights come from the “visual rhetoric” of this pottery. If we take the position that styles are modes of expression and communication, we must address questions about the content of the messages and the identities of senders and recipients. Who formatted the meaning, selecting the signs and images—the inferred elements of rhetoric—and determined their location on Petén Postclassic vessel surfaces? The differential spatial distributions of the decorated pottery suggest not only that variable information or messages were being sent but also that the intended audiences varied, raising issues of power.

Following semiotechnological concerns with “regimes of the production and circulation of meaning” (Langlois Reference Langlois2011:1), we can investigate the power formations that mobilized the symbols and styles. Postclassic Petén potters and decorators were probably male, as potters were in colonial northern Yucatán (Clark and Houston Reference Clark, Houston, Costin and Wright1998:34, 37), among the Lacandon (McGee Reference McGee1990:51; Soustelle Reference Soustelle1937:39), and in the Classic period (Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet1994; Rice Reference Rice, Cecil, Rice and Rice2009).They were members of an interpretive community that possessed a powerful visual rhetoric of shared beliefs—Sonja Foss's (Reference Foss, Hill and Helmers2004:307) underlying “concepts, ideas, themes, allusions,” or meanings, in other words—that they activated through motifs and layouts. This rhetoric included vocabularies of design structures and icons with histories dating back into the Classic period, such as quadripartite bands, red and black colors, mats, and certain glyphs; others drawn from the Quetzalcoatl cult, such as reptile heads and RE glyphs; and still others from the Late Postclassic International painting style. Decorators may have also possessed a degree of hieroglyphic literacy that would have informed use of some of the motifs.

If we consider Petén Postclassic decorated pottery to be a “meaning-full” semiotechnology, what were the power relations underlying the production and circulation of its meanings? Itza potters may have produced elaborately decorated pots and unusual forms specifically for elite patrons at the island capital. Circulation of these items may have been restricted, given that such highly decorated wares are rare at mainland sites. Patrons may have encouraged stylistic innovation and the potters may have felt free to innovate, perhaps competitively, creating the numerous decorative variants of SIP pottery recovered at Tayza but absent elsewhere. These innovations, which potters creatively negotiated by combining them with traditional, timeless vessel forms, colors, layouts, and icons, can be construed as elites asserting new affiliations and sources of political power.

The most dramatic innovation in Petén Postclassic pottery was the Kowoj's creation of the red-painted, swirly, distributive style (Rice Reference Rice1979). The circumstances of this style's origins are unclear, but the Late Postclassic was a time of expansion, in-migration, factionalism, and growing hostilities between Kowojs and Itzas. This highlights another of Wobst's proposals: in times of competition and social stress, group-specific styles will be mobilized to signal affiliations, statuses, and boundaries. I consider the later adoption of this style in the Itzas’ SIP ware (Macanché Red-on-paste: Macanché variety) to reflect the Kowoj–Chakʹan Itza factional alliance.

One avenue to understanding the circulation of meaning—and the semiotechnological and rhetorical meaning of the decoration itself, as well as its active agency within sociopolitical networks—relates to contexts. Context here concerns both the spaces on the vessel surfaces on which the embellishment appears and the sociopolitical contingencies in which these containers were mobilized. Decoration on serving vessels’ interiors transmits messages that can be decoded by members of the interpretive community who are using or are physically close to the vessel, manipulating or consuming the contents. But such information would have been obscured by those contents (unless they were clear liquid) and largely invisible until the vessels were emptied. Exterior decoration, particularly its structure, displays information not only to persons nearby but also to those viewing the pottery from a greater distance, which might include those outside the interpretive community. On vessels with restricted orifices, for example, decoration is on the exterior.

On the large bowls and basins in the southeast quadrant, this decorative rhetoric appeared on both interior and exterior, suggesting more forceful and simultaneous proclamation of varied identities, affiliations, and power to an audience. These vessels might have been used in the kinds of “diacritical feasts” described among the Classic Maya (Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2016:25; see LeCount Reference LeCount2001), or possibly larger inclusionary affairs. Similarly, the intricate fine-line incising of Picú Incised may appear on both interior and exterior, making the messages especially complex to decode. This may reflect the visually restricted and privileged use of the vessels in the ceremonial center of the capital, with locally (i.e., priestly) specific themes, per Wobst.

Conclusions

This essay has examined the styles—design structures, colors, motifs, and icons—and meanings of decorated Postclassic pottery made and used by the Postclassic- and contact-period Itzas of central Petén, Guatemala. Tayza was the island capital of the powerful and pluralistic Itza kingdom, its residents interacting with immigrants, trading partners, and neighboring—often antagonistic—ethno-linguistic-political groups. The island was said to be occupied by provincial governors (and their families and retinues), and large pottery vessels played conspicuous rhetorical roles in civic-ceremonial activity. These objects, prominent in serving sizeable groups, visually communicated power by their sheer size and elaborate decorations.

Style has been defined as practice, as “a way of doing” (Hegmon Reference Hegmon1992:517–518), but I see it also as a “way of meaning.” The varied spatial distributions of pottery styles on the noj peten, as brought to light through this unsatisfactory—but nonetheless unique and culture-historically significant—sample, provide a preliminary basis for interpreting meanings. The central and southern sectors yielded greater quantities of both pottery in general and pottery with more elaborate decoration, particularly in the southeast. Such decoration—on vessel interiors and exteriors—was rare to nonexistent at Itza mainland sites. The stylistic complexity likely relates to multilayered identities of residents of (and visitors to) the Itza capital, and probably helped the Itzas and Kowojs confront the complexities of their world.

The southeast quadrant is particularly interesting as the proposed location of the residence of Ajaw Kan Ekʹ. Throughout the south, but especially in the southeast, the colors, layouts, and motifs on SIP pottery were singularly emblematic of Itza supreme leadership. Meanings were conveyed internally to users and externally to a viewing audience of visiting elite “others.” Rhetorically, the pottery communicated messages of elite or royal status, wealth, power, legitimacy, and singularity.

The northern part of the island displayed fewer but locally and regionally significant motifs (primarily reptilian—signifying some identification with the feathered serpent cult—and mats) and more traditional colors and design structures, such as Ixpop Polychrome. Moreover, Ixpop is the most common decorated type at Itza mainland sites. This traditional, conservative, banded layout and associated motifs proclaimed a collective Itza ethnopolitical sense of “us” throughout the Lake Petén Itzá basin. Rhetorically, Ixpop's “meaning” was integrative, reinforcing the enduring politico-religious power of the regionally feared Itza confederacy and its leadership. It communicated Itza identity.

The pottery and related materials on which this preliminary study is based were, unfortunately, recovered under less than ideal circumstances and thus the conclusions that can be confidently drawn are limited. Nonetheless, the multipronged theoretical and methodological approach to interpreting decorative style developed here is applicable to a variety of circumstances where intense urban construction precludes extensive, systematic archaeological investigations. Minimally, this approach and similar attention to serendipitous finds can be used to develop hypotheses that can later be tested, should such opportunities appear, whether at Tayza or at other, similar urban sites. In the case of Tayza, to ignore this material because of lack of proper provenience controls would be to disregard a significant complement to sparse Spanish documentary sources on the contact-period Itzas, and to ignore a rare glimpse into the material and visual culture of the capital of the last Maya kingdom to fall to the Spaniards.

Acknowledgments

My work in Petén was facilitated through a permit granted to Timothy W. Pugh by the Guatemalan Instituto de Antropología e Historia. In 1997 Richard Hanson and Donald Forsyth generously allowed me to study the pottery they recovered from authorized excavations on Flores. I thank Mario Zetina, who kindly gave me access to pottery from some of the later public-works projects on the island. Leslie Cecil and I examined pottery from the 2004 project thanks to the late Julio Roldan. I am grateful to Marco Tulio Pinelo for the opportunity to study the sherds he collected from the southeastern quadrant. Cynthia Kristan-Graham contributed important insights into visual culture that greatly enriched my interpretations. Thanks, as always, to Don Rice for the illustrations. No financial or institutional conflicts of interest exist.

Data Availability

Data are available in the published sources cited in this paper. Additional data may be made available for research purposes by contacting the author.