Combine several well-established theories of the sociology of knowledge and motivated reasoning with a good deal of data demonstrating the dominance of an ideological perspective in the discipline and a host of serious problems rear their ugly heads: self-satisfied arrogance and denial on the left; resentment and paranoia on the right; ideologically skewed and sloppy research and teaching; and an erosion of trust, respect, and support for the discipline. Multiply that across the fields of academia as well as journalism and science more broadly and you have a brewing national crisis, claims and counterclaims of fake news and fake science, and a breakdown in the trust of society’s knowledge institutions as honest brokers. Good luck restraining intense differences of polarized politics when each side claims a monopoly on the truth and believes its opposition suffers from delusions and distorted perceptions.

THE IGNORED BREAKDOWN

The progress of any collective intellectual enterprise depends on the fair and vigorous competition of ideas. Scholars from different perspectives are needed to challenge one another so that findings, interpretations, and conclusions are honestly and rigorously tested; that different hypotheses are raised and considered; and that a wide range of interesting questions are asked and explored. With liberal perspectives now prevailing in political science and across academia, that competition of perspectives has broken down. This is especially troubling when ideological implications are involved, as they often are.Footnote 2 The lack of ideological diversity affects every aspect of the profession, from those who enter and stay as students and faculty to what is researched, published, and taught.

Despite the pervasiveness of the problem, it has been ignored by most political scientists and the discipline’s leadership. Unimpeded, it has grown more severe. Whether from denial or indifference, the lack of ideological diversity is not high on the APSA’s agenda or that of most of its members; it does not even warrant an APSA committee. The lengthy list of APSA “status” committees includes blacks, Latinos, Asian Pacific Americans, women, lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgenders, but there is no committee on intellectual diversity (or on conservatives). In the APSA Task Force’s 74-page report on Political Science in the 21st Century, there was not a single mention of ideological or intellectual diversity—and this in a profession whose raison d’etre is the intellectual understanding of politics.

Why the utter lack of concern? One reason is that many of the consequences of ideological homogeneity go unnoticed. What diversity there was has eroded gradually, and those in the dominant majority have not been disturbed by its loss. Likeminded scholars tend to like what other likeminded scholars do and everything proceeds smoothly. Who has reason to notice or do anything about the questions unasked about different subjects, alternative hypotheses arising from a different perspective, measurements and tests that might not have been pushed hard enough, or different interpretations of findings? Business is as usual. The status quo is comfortable for those on the dominating ideological side. They do not think it is broken, it works for them, so what needs to be fixed?

For those on the minority conservative side, however, the problem of ideological homogeneity is plainly obvious—and it is not only a problem for whining conservative malcontents. Whether recognized or not, it is a problem for everybody—moderates, liberals, political science as a discipline, and those in the broader public seeking a better understanding of politics.

For those on the minority conservative side, however, the problem of ideological homogeneity is plainly obvious—and it is not only a problem for whining conservative malcontents. Whether recognized or not, it is a problem for everybody—moderates, liberals, political science as a discipline, and those in the broader public seeking a better understanding of politics.

IDEOLOGICAL ORTHODOXY IN ACADEMIA

Although there is not much data specifically on the distribution of ideological perspectives within political science (perhaps owing to ideological orthodoxy being a common condition across academia), a good deal of data have been collected about the ideologies of social scientists and academics more generally.Footnote 3 Since Ladd and Lipset (Reference Ladd and Martin Lipset1975) studied the matter nearly a half-century ago, the American professoriate has become much more politically liberal than it was, both across academia as well as within the social sciences (Brookings Institution 2001; Klein and Stern Reference Klein and Stern2005; Konnikova Reference Konnikova2014; Maranto and Woessner Reference Maranto and Woessner2012; Mariani and Hewitt Reference Mariani and Hewitt2008; Rothman, Lichter, and Nevitte Reference Rothman, Lichter and Nevitte2005).

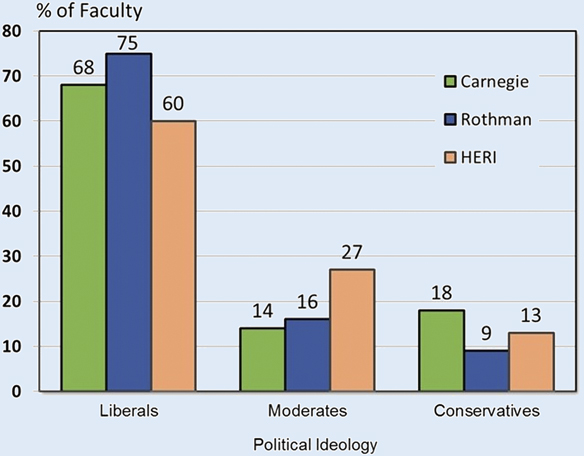

Figure 1 presents the ideological distributions of social science and general undergraduate faculties reported in three studies. The first series is of social scientists from the National Survey of Faculty in 1997 (Zipp and Fenwick Reference Zipp and Fenwick2006).Footnote 4 The second series, also of social scientists, is from the 1999 North American Academic Study Survey (NAASS) (Rothman, Lichter, and Nevitte Reference Rothman, Lichter and Nevitte2005).Footnote 5 The third series includes all faculty (because the subset of social scientists was unavailable) from the 2013–2014 Undergraduate Teaching Faculty Survey conducted by the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) at the University of California–Los Angeles (Eagan et al. Reference Eagan, Stolzenberg, Berdan Lozano, Aragon, Suchard and Hurtado2014).

Figure 1 Political Ideologies in Social Sciences and Academia in Three Studies

Despite some differences, these data document how little ideological diversity there now is in the social sciences and across academia. Other studies concur (Gross and Simmons Reference Gross and Simmons2007; Luntz Research 2002). A study of the party registration of faculty in 51 liberal arts colleges, for example, found that political science faculty were more than eight times more likely to register as Democrats than as Republicans (Langbert Reference Langbert2018). Other studies of smaller sets of institutions, campaign contributions, party identifications, and recalled vote choices, as well as the few studies that could be filtered to political scientists, confirm a strong liberal skew.Footnote 6

It is hardly surprising that a large majority of social scientists are liberal. What is notable, however, is the degree of homogeneity and that this liberal homogeneity is embedded within a general public in which conservatives have outnumbered liberals since at least the 1970s, when standard survey questions on political ideology became regularly available. About 36% of Americans report they are conservatives and only about 22% declare themselves liberals (Campbell Reference Campbell2018, 248). The American public is polarized with a tilt to the right. Academia is relatively unpolarized with a very strong skew to the left.

WHY LIBERAL DOMINANCE MATTERS

Liberal dominance of academia, including political science, is not seriously in question. Liberals in political science outnumber conservatives by a wide margin and even outnumber conservatives and moderates combined. But does this make a difference?

According to some defenders of the faith, liberal dominance makes no difference. As they see it, there is no significant evidence that it affects what we study, how rigorously we examine our research questions, how fair and effective our peer-review process is in separating the wheat from the chaff, what gets published and promoted by the best journals and presses, who takes our classes and is admitted to our best programs, which faculty are hired or promoted, who gets awards and recognitions, who runs our journals and associations, what is taught to our students, and so on. The contention is that our political beliefs make no difference in our study of politics.

Hard to believe? Impossible to believe. Impossible based not only on experience but also on common sense as well as a raft of highly confirmed theories about human behavior. Political science, as in every intellectual enterprise, allows for a great deal of discretion—and discretion leaves the door open for bias, the application of one’s values and preferences. Rigorous methodologies can restrain this, but not as much as we might like to think. There are choices to be made at every stage of every analysis. Furthermore, some methodologies provide precious little restraint to the application of a scholar’s opinion. Moreover, even the most rigorous methodologies provide no restraint to interpretations, commentary, and many other decisions we make.

Professionalism, the commitment to “getting it right,” fairness, and seeing issues from the other side may also impede bias, but this self-restraint goes only so far. We are not always on guard about bias (and it does not take many behaving unprofessionally to wreak havoc when a single negative anonymous review can kill an article’s acceptance or a promotion case) and sometimes we are not as critical about our own work as we ought to be. Political scientists are humans (perhaps with a few exceptions), which is to say imperfect. As James Madison wistfully wrote, “[i]f men were angels....” Well, they are not and neither are women (to amend Madison); so bias happens.

Even full adherence to rigorous methodologies and complete dedication to professional standards—neither of which can be realistically expected—would still allow bias to creep into our work. As in politics, ultimately, the best way to bring bias to light and to keep it in check is through the vigorous competition of political perspectives. Our ideological orthodoxy has cost us a great deal of this healthy competition of perspectives, especially on matters most politically relevant.

THE IRON THEORIES OF ORTHODOXY

The conclusion that the lack of ideological diversity has had no impact on the profession defies three highly regarded, well-established, and interrelated theories of science and human behavior. First, Kuhn’s (Reference Kuhn1962) landmark treatise on The Structure of Scientific Revolutions makes a strong case for the sociology of knowledge. A prevailing view develops an inertia or something of an immunity from challenge—what could be interpreted as “groupthink.”

Second, Noelle-Neumann’s (Reference Noelle-Neumann1984) classic study of the power of orthodoxy, The Spiral of Silence, explains how dominant views within a group intimidate those in the minority, inducing their quiescence. Those in a distinct minority “lay low” to avoid drawing attention to their deviant views. “Go along to get along” or, at least, keep your differences to yourself.Footnote 7 Although there is no obvious threshold of when a majority becomes large enough to induce submission by the minority, the lopsided distributions of figure 1 appear well into intimidating territory.

The third theory is actually a group of widely accepted theories of predisposition reinforcement, confirmation bias, and motivated reasoning (Glynn et al. Reference Glynn, Herbst, Lindeman, O’Keefe and Shapiro2016; Klapper Reference Klapper1960; Kunda Reference Kunda1990; Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013; Nickerson Reference Nickerson1998). People are inclined to believe what they already believe and disinclined to believe what they do not already believe. Preexisting views are defended. If the preexisting views of the group are mostly liberal, good luck in convincing them of anything not fitting or reinforcing those views.

So, can we believe that political scientists are somehow exempt from these theories that describe and explain thought and behavior everywhere else? In a word, no.

Based on these theories, it would be extraordinary for political science—or any discipline so homogeneously liberal—to be anything but particularly welcoming to those producing and teaching research friendly to liberal views and far less receptive to conservatives. In the context of our highly polarized politics, these differences are magnified. So, can we believe that political scientists are somehow exempt from these theories that describe and explain thought and behavior everywhere else? In a word, no.

THE TRUTH ABOUT CONSEQUENCES

If these theories provide strong reasons to suspect harmful consequences from ideological orthodoxy, why have these effects not been detected in general analyses? I suspect they have largely escaped detection because, as one would expect, these effects are neither overt nor easily measured. This does not, however, make them any less real. Journal reviewers, for example, would not explicitly admit—or might not even be aware themselves—that they are recommending acceptance of a submission because they favor the ideological implications of its conclusions. This does not mean, however, that they have not given the piece a more sympathetic reading if it came from a perspective they share or are not pickier about a piece opposing their views. Any of the dozens of things we do or decide about (e.g., in writing and research, teaching and grading, hiring and firing, and public commentary) could be substituted in place of the reviewing of a journal submission to understand how bias routinely “flies under the radar.”

In my experience, the effects of liberal orthodoxy have been exhibited in many ways. Some are clearly linked to the imbalance of ideological views and others I have only suspicions of a link. Some do not amount to much (but should not happen) and some are more serious (e.g., a horror story involving a paper challenging research claims favorable to the Democrats and a reviewer at a prominent journal claiming that I was “perhaps dishonest” and “making stuff up” though the data were easily accessible government-collected data I had already shared with the editor!). Others are not quite so outrageous and still others I have heard about from a distance. Some are within political science and some are with university “colleagues” in other disciplines (e.g., use of a broad listserv to faculty with nasty slurs directed at conservatives, apparently assuming none could possibly be on the listserv). Some are personal and some institutional—for example, the APSA’s failure to speak up in defense of John McAdams’s academic free speech against its infringement by his university’s administration (Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty 2019).

As troubling as many of these consequences of ideological orthodoxy have been, its most disturbing effects concern students. I suspect a good deal of student cynicism and the game-playing approach to academics (e.g., passivity or humoring professors by feeding back to them what they have been taught) is associated with ideological orthodoxy. Several years ago, I received an email from a student at another university asking to chat at the APSA meeting. He was deciding whether to go to graduate school in political science and had concerns about how he might be treated as a conservative. Another very gifted conservative student told me he was not going into the profession because it was “too far gone.” This is a shame.

THE WINNERS AND THE LOSERS

If history is any guide, and it usually is, like past complaints about the lack of ideological diversity, this one will fall on deaf ears—dismissed as whining; or not conclusively proving the general ill-effects of orthodoxy; or not taking into account that liberals are simply smarter, more hardworking, or more deeply caring about politics, inequality, and social justice. Behind those denials is the comfort the status quo provides liberals and those posing no challenge to them. They are the winners in this situation—at least in the short run—and perhaps that is all that matters to them.

In the long run, however, ideological orthodoxy serves no one well. Most obviously, conservatives face a hostile environment for their work. It normally is not openly hostile, but certainly not as hospitable as it is for others. Less obvious is the cost to liberals. They may not be challenged as strenuously as they would be in a more ideologically diverse climate. We might expect their work to be not as sharp as it might have been otherwise had it gone through the rigors of a more critical process. Drawing again on personal experience in reviewing submitted work and responding to already published work with liberal implications (some award-winning), most work can benefit from input from both sides of the spectrum. This is a premise of peer review—but a premise no longer safely assumed, at least as far as ideology matters.

The big loser in the long run is the discipline itself and those who might look to it for a serious and dispassionate understanding of politics. Its legitimacy as an academic discipline rests on being regarded as above politics or, at least, balanced in its politics. If it is perceived as politicized—as it already is regarded by many (witness the frequent attacks on the National Science Foundation’s political science program)—those in the center and on the right will perceive it as a propaganda mill of the left rather than a serious and authoritative source of knowledge (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2009; Fain Reference Fain2017). Students may still come by to have their tickets punched for their diplomas and liberals will come by to elaborate their perspectives, but the enterprise will continue to suffer diminished public esteem, trust, and support.

BIGGER THAN POLITICAL SCIENCE

The problems associated with the lack of ideological diversity are by no means limited to political science. They are problems throughout academia—worse in some sectors than in others, but problems in virtually every field (Abrams Reference Abrams2018; Eagan et al. Reference Eagan, Stolzenberg, Berdan Lozano, Aragon, Suchard and Hurtado2014; Klein and Stern Reference Klein and Stern2005; Konnikova Reference Konnikova2014). Liberal orthodoxy extends as well into journalism (Groseclose Reference Groseclose2011) and across the natural sciences. A 2014 survey of members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science found 57% liberals, 32% moderates, and only 9% conservatives (Pew Research Center 2015, 30).

As it now stands, knowledge institutions in America—higher education, journalism, and science—are dominated by liberals. The American public, on the other hand, is highly polarized with a tilt away from liberals. Is it any wonder that Americans—particularly moderate and conservative Americans—have lost their trust in what these institutions have to say? According to Gallup (Swift 2017), only 14% of conservatives trusted the national media for full, accurate, and fair news coverage. According to Pew, 73% of Republicans think higher education is moving in the wrong direction and most (79%) attribute this to the political leanings of professors (Brown Reference Brown2018). The trust in our knowledge institutions has deteriorated, and this will make compromise in our polarized politics all the more difficult.

SO, WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

First, we should admit that, like polarization of the public, there is no “big fix” for the ideological orthodoxy of our discipline. The problem is too wide (across all knowledge institutions) and too deep (ingrained in our fundamental orientations). So, we can either resign ourselves to growing ideological homogeneity and the dismal future that entails or take whatever small steps we can to address the lack of intellectual diversity.

As in other dilemmas of collective action, the only hopeful course is to do what we can to make a difference, however slight. In that regard, I have two suggestions. The first is for the APSA to declare (or admit) that ideological orthodoxy is a serious problem. Second, the APSA should formally endorse the statement of purpose of Heterodox Academy (2019) and work with it on ideas to increase viewpoint diversity. Ideological orthodoxy is a broad problem, and it might be fruitful to work with those across other disciplines dealing with the same problems. These are small steps, but even small steps should be welcomed by conservatives in the profession who would like a reason to disagree with those telling them that the discipline is “too far gone.”