Toward an Alternative Understanding of Cultural Interaction in the Caribbean

The mixing or blending, the homogenizing or cultural merging, the diverging or converging cultural, linguistic, and genetic transformations or transitions from one culture to another or in acquiring another culture as a consequence of or related to European colonization processes, the plantation economy, subjugation, cultural hegemony, or globalization have been referred to as processes of acculturation, deculturation, syncretism, transculturation, ethnogenesis, hybridization, métissage, and creolization (e.g., Cusick Reference Cusick1998; Glissant Reference Glissant1997; Hannerz Reference Hannerz1987; Mintz and Prize Reference Mintz and Price1976; Mullins and Paynter Reference Mullins and Paynter2000; Ortiz Reference Ortiz1995; Silliman Reference Silliman2015; Stewart Reference Stewart2016; Stockhammer Reference Stockhammer2012). These concepts vary in meaning among scholars, countries, and world regions, and their use has been challenging because of their different meanings in diverse settings, the differential impact of colonialism on the various peoples still visible today, and the incorrect analysis of the long-term and spatially diverse processes with unlimited sociocultural interactions and inclusion of all peoples (for a general review and reflection on these concepts, see Silliman Reference Silliman, Orser, Zarankin, Funari, Lawrence and Symonds2020).

The development of the concept of creolization has been synonymous with the Caribbean and the formation of its multi- and transcultural societies following the European invasion of the Americas. The voluntary and involuntary cultural interweaving of various communities through conquest, enslavement, and colonization forged new societies and identities, making the Caribbean a unique microcosm of cultural interaction and change (Bolland Reference Bolland1998; Glissant Reference Glissant1997; Hannerz Reference Hannerz1987; Palmié Reference Palmié2006; Webster Reference Webster2001). Creolization was viewed as having occurred in a precise time and space and under the specific conditions of the cultural interactions between primarily Europeans and Africans, melding in a cauldron of enslavement and colonialism, with the role of the Indigenous peoples who occupied the Caribbean islands not seen as integral to that process (Brathwaite Reference Brathwaite1971; Glissant Reference Glissant1997, Reference Glissant2008; Mintz and Price Reference Mintz and Price1976). Recently, it has become evident that this process can be applied to multiple societies worldwide and in various eras by using similar metrics to understand their formation (e.g., Hannerz Reference Hannerz1987; Khan Reference Khan2001; Palmié Reference Palmié2006). As a result, the process of creolization is being applied to the broader understanding of blended societies as old as the Roman Empire and as far away from the Caribbean as the Pacific, demonstrating the applicability of the approach in examining cultural interaction and change under variable conditions and in fluctuating time periods and locations (Birmingham Reference Birmingham, Torrence and Clarke2000; Webster Reference Webster2001). In the broader context of the research presented here, it has also been applied to study material culture and the processes of appropriation, integration, and reinterpretation of objects produced by interacting populations. Since the late 1970s, it has been used to describe stylistically mixed artifacts, with a focus on cultural dynamics and social interactions with diverse spatiality and temporality (see Ferguson Reference Ferguson2000; Stewart Reference Stewart2016; van Pelt Reference van Pelt2013).

This broader application of creolization has in turn had an impact on how the process is understood in the Caribbean. It is now clear that the concept should be used to increase understanding of the region's entire history, including before European colonization; of cultural interactions seen through human mobility and the exchange of ideas and goods; and by incorporating the Indigenous population as an integral part of the process in the colonial period (Curet Reference Curet and Lozny2011; Khan Reference Khan, Palmié and Scarano2011). An area such as the Windward Islands, for example, was a space where peoples and ideas from both the Lesser and Greater Antilles blended with those from the South American mainland and later with those from Africa and Europe, creating new identities and societies (Ferguson and Whitehead Reference Ferguson and Neil L.1992; Hofman, Borck, et al. Reference Corinne L., Borck, Laffoon, Slayton, Scott, Breukel, Falci, Favre and Hoogland2021; Hulme Reference Hulme1986; Sued Badillo Reference Sued Badillo and Whitehead1995). The Windwards can be described as a Caribbean crossroads because of its geographic position and the spontaneous creation of a cultural and biological open space. From the onset of settlement, these islands received a continuous infusion of people, materials, and ideas, which increased after European colonization (e.g., Boomert Reference Boomert2000; Curet and Hauser Reference Antonio and Hauser2011; Hofman and Bright Reference Hofman, Bright, Hofman and Bright2010; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Mol, Hoogland and Rojas2014). The Windwards retained strong and continuous links to the South American mainland after colonization; there was a constant movement back and forth in almost every aspect of society. For example, legal and illegal trade between the southern Caribbean and northern South America occurred well into the 1800s (Goslinga Reference Goslinga1971; Watts Reference Watts1987). The islands also retained a strong Indigenous heritage via the Kalinago, Kalina, and other ethnic groups for a sustained period. Biological and cultural diversity continued because of the islands’ crossroads status and the diversity of European colonizers—Spanish, Dutch, French, English, and even Portuguese from South America—who visited and partly settled the archipelago. The interactions among the Indigenous populations (on cultural and biological levels) of the Kalinago, Kalina, the so-called Taino, and others, and later with Africans, Europeans, and Asians, resulted in the creole societies that are celebrated today. Thus, the Windward Islands can be viewed as a fluid space up until the 1760s, by which time all the islands had fallen under the control of European colonizers, with Indigenous-dominated islands (Saint Vincent and Dominica) losing their status as “neutral” territories (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019).

The first objective of this article is to examine some possible witnesses to the complex process of creolizationFootnote 1 in the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles (Figure 1) through the lens of material culture and via a longue durée perspective (sensu Braudel Reference Braudel1958). We look at the cultural interactions expressed in stylistic data and the manufacturing processes of ceramic traditions that emerged among the Indigenous inhabitants before European colonization. These interactions increased after colonization, expanding to include interactions between the various Indigenous peoples and diverse African ethnic groups. We discuss contemporary Afro-Caribbean potters in the southwestern district of Saint Lucia where the legacies of the Indigenous–African–European cultural dynamics in society today come to the fore. The second objective of this article is to demonstrate how a detailed and homogeneous technological analysis of the ways of doing things makes it possible to better understand the similarities and differences in ceramic assemblages, which contributes to the debate on creolization. We review published data and conclude with an example of a detailed analysis of the chaîne opératoire, or operational sequence.

Figure 1. Map of the Caribbean with insert of the Lesser Antilles showing the Indigenous sites mentioned in this article (figure by Menno L. P. Hoogland).

Kalinago/Kalipuna Society in the Windward Islands

The Lesser Antilles were first settled between about 8,000 and 5,000 years ago by people traveling to the islands from both South America and possibly Central America via the Greater Antilles (Hofman and Antczak Reference Hofman and Antczak2019; Pagán-Jiménez et al. Reference Pagán-Jiménez, Ramos, Reid, van den Bel and Hofman2015). These first settlers occupied both the coastal and interior parts of the islands, transformed the island environments, practiced plant management, and maintained a yearly mobility cycle based on seasonality and resource availability. The onset of agriculture in the archipelago was not a sudden event, but on the contrary was the result of a process of fusions and mixtures of endogenous and exogenous traditions among myriad groups of peoples in the so-called Archaic and Ceramic ages (Hofman and Antczak Reference Hofman and Antczak2019; Rodríguez Ramos Reference Rodríguez Ramos2010). Between cal 400 BC and AD 400, most islands of the Lesser Antilles were inhabited, gradually intensifying their social relationships and creating a vast web connecting island communities to each other and to mainland communities (e.g., Bérard Reference Bérard2019; Crock Reference Crock2001; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Bright, Boomert and Knippenberg2007). Throughout their entire precolonial history, the Lesser Antilles are known to have been a dynamic arena where people from different areas of the insular Caribbean and the coastal zone of mainland South America interacted (Boomert Reference Boomert2000; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Boomert, Bright, Hoogland, Knippenberg, Samson, Antonio Curet and Hauser2011). Intensive networks of human mobility and exchange of goods and ideas created various ethnic and cultural communities across the region, today designated with such labels as “Taíno,” “Carib,” “Huecoid,” “Saladoid,” “Ostionoid,” “Troumassoid,” “Meillacoid,” “Suazoid,” “Chicoid,” and “Cayoid” (e.g., Boomert Reference Boomert2000; Keegan and Hofman Reference Keegan and Hofman2017; Rouse Reference Rouse1992). However, it is important to realize that these labels mask a diversity of human agency reflected in the archaeological record of the Caribbean, resulting from complex fissions and fusions and the constantly shifting alliances among its various Indigenous peoples (Bright Reference Bright2011; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Mol, Hoogland and Rojas2014; Rodríguez Ramos Reference Rodríguez Ramos2010; Ulloa Hung Reference Ulloa Hung2014). In other words, the process described today as creolization invariably formed an attribute associated with the archipelagic constellation of Caribbean society before European colonization.

During the sixteenth century, most of the larger Caribbean islands and parts of the mainland were settled by the Spanish (Keehnen et al. Reference Keehnen, Hofman, Antczak, Hofman and Keehnen2019). Their lack of interest in the Lesser Antilles and a series of settlement ventures that failed partially because of the fierce resistance of Kalinago/Kalipuna kept these islands beyond their control. During the early years of colonization, Spanish slavers raided the Lesser Antilles, and from 1503 Real Cédulas were issued by the Spanish Crown, legally permitting the capture and enslavement of the Indigenous peoples under the pretext that they were man-eaters (Ferguson and Whitehead Reference Ferguson and Neil L.1992; Hulme Reference Hulme1986). Simultaneously, the Lesser Antilles functioned as a refugium for peoples from the Greater Antilles, as well as the South American mainland, who in some cases served as “middlemen” in the trade between the Spanish Caribbean and continental South America (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019; Sued Badillo Reference Sued Badillo and Whitehead1995). Approximately 130 to 150 years passed until other European nations permanently settled in these small islands despite fierce “Island Carib” (Kalinago/Kalipuna) resistance. The Kalinago/Kalipuna claimed origin from the mainland and lived in a series of strongholds between Tobago and Saint Kitts (Allaire Reference Allaire and Wilson1997).

The Island Carib represented a creole society as shown by linguistic, anthropological, and archaeological evidence (Honychurch Reference Honychurch2000; Taylor and Hoff Reference Taylor and Hoff1980). They spoke two variants of what was basically Maipuran Arawakan: a female and a male register, of which the latter showed numerous Cariban lexical borrowings. This male register originated as a contact vernacular (pidgin) bridging the gap between Maipuran Arawakan, the women's native tongue, and Kalina, the Cariban language of the men (and women) who had immigrated into the Lesser Antilles from the South American mainland and mixed with the local population. The persistence of the Cariban-affiliated male register can be ascribed to the continuous interaction between the Island Carib and the Kalina of the Guianas for joint (male) expeditions of trade and war. Sociopolitically, Island Carib society closely resembled that of the mainland Kalina as is reflected in, for example, the layout of their villages (Boomert Reference Boomert1986). The Island Carib men used the name “Kalinago” to refer to their people, a term derived from Kalina to which the honorific suffix –go was added, illustrating feelings of joint ethnicity with their mainland kinsmen. The Island Carib women, however, used the Maipuran Arawakan term “Kalipuna” as the name of their people (Hoff Reference Hoff1995; Taylor Reference Taylor1977; Taylor and Hoff Reference Taylor and Hoff1980).

The early chroniclers depicted the southern Lesser Antilles as land and seascape contested by the various Indigenous peoples and the Europeans (e.g., Anonyme Reference Anonyme, Roget and Crosnier1975 [1659]; Anonyme de Carpentras 2002 [ca. 1618–1620]; Breton Reference Breton1665, Reference Breton1666, Reference Breton1978; Chanca Reference Chanca and Jane1988 [1494]; Coppier Reference Coppier1645; Du Tertre Reference Du Tertre1667–1671; Labat Reference Labat2005 [1722]; Nicholl Reference Nicholl1605; Pinchon Reference Pinchon1961; Rochefort Reference Rochefort1658). The Windward Islands, containing dominant populations of Indigenous peoples with direct links to South America where they raided and traded, represented the last remaining stronghold of the Kalinago (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019). Throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries there are multiple reports of concerted efforts by the Kalinago/Kalipuna and others to defend this highly contested space against the Spanish and their local allies (Boucher Reference Boucher1992; Cody Holdren Reference Cody Holdren1998; Martin Reference Martin2013; Shafie et al. Reference Shafie, Schoch, Mans, Hofman and Brandes2017). However, from the 1620s onward, the Indigenous peoples of the Lesser Antilles were besieged by the English, French, and Dutch who invaded the islands and successfully established colonies (Du Tertre Reference Du Tertre1667–1671).

The existence of the early colonial Island Carib has long been doubted because of the lack of archaeological evidence (Davis and Goodwin Reference Davis and Christopher Goodwin1990; Ferguson and Whitehead Reference Ferguson and Neil L.1992; Hulme and Whitehead Reference Hulme and Whitehead1992), and they were regarded by anthropologists and archaeologists as a culture that developed after European colonization. They were seen as the inheritors of all the cultural traditions of the Indigenous Caribbean peoples and the mainland Kalina/Galibis, who temporarily manifested themselves on the empty stage of the early colonial period (Boomert Reference Boomert1986; Hofman and Hoogland Reference Hofman and Hoogland2012; Honychurch Reference Honychurch2000; Sued Badillo Reference Sued Badillo and Whitehead1995). A pattern of exchange developed in the late sixteenth century between the European nations and the Kalinago/Kalipuna, which culminated in their cultivation of tobacco for sale to passing European traders (Boomert Reference Boomert2002; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019) and in the first European trading posts on the islands with evidence of Kalinago/Kalipuna presence (Hauser et al. Reference Hauser, Armstrong, Wallman, Kelly and Honychurch2019). Early colonial Spanish, Dutch, French, and English sources provide vivid testimonies of the slow but inevitable encroachment of European nations in the Lesser Antilles and the marginalization of Indigenous culture and society. Meanwhile, Island Carib communities on some of the islands absorbed increasing numbers of escaped enslaved Africans (originally from west and west-central Africa), leading to the formation of a “Black Carib” ethnic identity alongside those communities that remained purely Indigenous (“Yellow Carib”; Gullick Reference Gullick and Whitehead1995). Many “Black Carib” were deported from Saint Vincent to Central America in 1797 by the English, where they still self-identify as Garifuna, which obviously is a derivative of Kalipuna, the name by which women in Island Carib society referred to their people. The Kalinago/Kalipuna on other islands of the Lesser Antilles such as Grenada are known to have taken both Africans and Europeans as captives, shaving their hair and piercing their ears as signs of enslavement (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019; Martin Reference Martin2013).

The Indigenous peoples of the Lesser Antilles first encountered captive Africans by the mid to late 1500s. They had been brought to the region by the Portuguese and others and put to work on the Spanish plantations in the Greater Antilles and South America. There are reports of several enslaved Africans being captured by Indigenous groups like the Kalinago/Kalipuna as part of their raiding, captive-taking, and trading activities (Barome Reference Barome1966; Boucher Reference Boucher1992; Moreau Reference Moreau1992; Pritchard Reference Pritchard2004). These African captives were taken to the Indigenous villages where they were reportedly kept as “slaves,” working as household workers, concubines, and laborers for menial tasks. As late as April 1658 two Africans who had been captured from the Portuguese and enslaved by the Kalinago were caught running away by French colonists; the Africans begged to be rescued because they could not live among the “savages” as they were “Christians” (Anonyme Reference Anonyme, Roget and Crosnier1975 [1659]:163). Incidents like these, though limited and also little researched, suggest early interactions between Africans and the Indigenous peoples of the region. But it is the often-reported wrecking of a slave ship on Saint Vincent in the sixteenth century and the immigration of escaped slaves from other islands, especially Barbados, that resulted in the creation of the historical “Black Carib” of Saint Vincent, which probably led to the most-referenced interaction between the two groups (Honychurch Reference Honychurch and Skelton2014; Taylor Reference Taylor1977).

Saint Vincent and Dominica were not officially colonized. The French and English designated these islands as “neutral” and left them in the possession of the Kalinago/Kalipuna until well into the eighteenth century. By 1800, a major collapse in the Indigenous population dramatically reduced the Island Carib presence in much of the Lesser Antilles, and the Indigenous populations became increasingly marginalized (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019). Descendants of the Kalinago/Kalipuna, however, still live today on Dominica, Saint Vincent, and Trinidad and are dispersed on other islands where they actively proclaim their Indigenous origins as an integral part of their identity in Caribbean society (Boomert Reference Boomert2016; Honychurch Reference Honychurch2000). The persistence of the Indigenous cultural traditions and knowledge in present-day creolized Caribbean society strongly counters the idea of their substitution, displacement, or disappearance, as suggested by traditional historiographies. Indigenous elements exist along with African and European ones and are still visible in forms of traditional agriculture (slash-and-burn; conucos, or small plots of cultivated lands), house building, an array of cultural traditions and ritual practices, and the intensive use of Indigenous plant species for economic and curative purposes, all aspects that constitute an important part of everyday life in the Caribbean today (Boomert Reference Boomert2016; Ulloa Hung and Valcárcel Rojas Reference Ulloa Hung and Rojas2016; Valcárcel Rojas and Ulloa Hung Reference Valcárcel Rojas and Hung2018). As such these intercultural dynamics are mirrored in today's locally produced creole, Afro-Caribbean earthenware or folk pottery, evidencing Suazoid and maybe some Cayoid influences (Fay Reference Fay2017; Hauser and Handler Reference Hauser and Handler2009; Hofman and Bright Reference Hofman and Bright2004; Vérin Reference Vérin1967). The longue durée approach taken in this study is thus more than justified, and our emphasis on ceramic traditions as an expression of sociocultural behavior in the creolization process is useful in reimagining the concept and emphasizing the oft-forgotten Indigenous component. It should be clear, however, that caution is called for in assuming that ceramics, traits, or, in this case, technological operations reflect specific identities (Dietler and Herbich Reference Dietler and Herbich1994; Hauser and deCorse Reference Hauser and DeCorse2003; Mouer et al. Reference Mouer, Ellen N, Hodges, Potter, Renaud, Hume, Pogue, MacCartney, Davidson and Singleton1999).

The Kalinago/Kalipuna Ceramic Tradition

The development of ethnological research in Caribbean ceramic studies has revealed the importance of technological studies focusing on pottery manufacturing processes (for a review, see Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland and van Gijn2008). Such studies investigate the link between chaînes opératoires and social groups (Roux Reference Roux2019). A social group may consist, for example, of a family, clan, caste, or ethnic group. Variability in the “way of doing” may be related to differences in these social groups, with each embedding potters in different social learning networks (Hofman, Hoogland, et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Jacobson, Manem, Boomert, Cristiana Barreto, Lima, Rostain and Hofman2021; Manem Reference Manem, Lehoërff and Talon2017; for studies outside the Caribbean, see Roux Reference Roux2019). Indeed, a way of doing things is “part of a heritage that develops on an individual (learning) [involving an interaction between a learner and a tutor whose way of doing things is the model to be reproduced through the acquisition of motor habits] and collective level (transmission)” (Roux Reference Roux2019:4). Therefore, a technical tradition is an inherited and transmitted way of doing things reflecting a social group. The social perimeter of its transmission is superimposed on the social boundaries of the clan, the ethnic group, and so on. Here, we focus on some steps of the production process—from clay sourcing to the finished product—illustrating the similarities and differences in technical and stylistic traditions through space and time to highlight possible processes of creolization. We argue that these processes reflect the cultural, economic, and social dynamics of a social group, as well as the persistence and continuities or discontinuities and transformations of practices through time.

Seventeenth-Century Descriptions of Island Carib/Kalinago/Kalipuna Pottery

According to the seventeenth-century European chroniclers, the production of Island Carib/Kalinago/Kalipuna pottery was in most cases carried out by women (Breton Reference Breton1665, Reference Breton1666). Few illustrations of this pottery are known, and their reliability is doubtful. The pottery includes open bowls and necked jars, some with handles and pointed or rounded bases. The descriptions allude to the existence of a ceramic repertoire of well-finished ceremonial vessels with Cariban names related to the men's realm, and of less finished domestic pottery with Maipuran Arawakan or European names related to the female sphere of activities (Boomert Reference Boomert1986, Reference Boomert and Whitehead1995). The male-connected vessels were employed for communal use during meals, the preparation of cassava beer, or serving that beer during drinking feasts. In contrast, the female-affiliated forms were used for purely domestic purposes. In all, 10 vessel shapes are described, of which some have both a female- and a male-associated name such as the griddle (boutalli or bourrelet) and the pepper pot (tomali acae or tomali hiem). The exclusively male-affiliated vessels include the chamacou, a beer-brewing container; the rita, a drinking bowl; and the taoloua or touloua, a serving bowl for cassava beer. The female-connected vessels comprise the rouara, a cooking pot, and the comori and boutella, both cooling jars for keeping liquids (Boomert Reference Boomert1986, Reference Boomert and Whitehead1995; Breton Reference Breton1665, Reference Breton1666; Hofman and Bright Reference Hofman and Bright2004). The manufacturing process is described in great detail in terms of clay processing, shaping, finishing or surface treatment, decoration, and firing. The mention of a wild tree resin used for the coating of vessel surfaces is noteworthy (Breton Reference Breton1665, Reference Breton1666). All-over red painting or the application of black designs on red surfaces is mentioned for couis, small calabash containers used for serving food and cassava beer, but not for pottery.

Suazoid and Cayoid Pottery before European Colonization until the Early Seventeenth Century

The archaeological quest for identifying the material evidence of the Island Carib presence in the islands has lasted decades (Bullen and Bullen Reference Bullen and Bullen1972; Davis and Goodwin Reference Davis and Christopher Goodwin1990). In the 1960s and 1970s a link was established with the so-called Suazoid ceramic series, which is still recognized as such in several islands. In the 1980s and 1990s, initial attempts were made to associate the Cayo complex of Saint Vincent with the Island Carib presence on the islands. This was based on stylistic and morphological similarities between Cayo and Koriabo ceramics from the Guianas (Boomert Reference Boomert1986, Reference Boomert and Whitehead1995). Koriabo is regarded as the ancestral pottery tradition of the contemporary Kalina or “Mainland Carib” of the Guianas and Orinoco Valley, which emerged in Suriname, French Guiana, the interior of the Guianas, and northeastern Brazil around AD 1100–1250 and continued to exist well into the early colonial period (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Lima, Rostain and Hofman2021; Boomert Reference Boomert1986; Rostain and Versteeg Reference Rostain, Versteeg, Delpuech and Hofman2004). Currently, about 20 Cayoid sites have been identified in the Lesser Antilles in the area between Grenada and Guadeloupe, with the majority documented on Saint Vincent, Grenada, and Dominica (Boomert Reference Boomert, Delpuech and Hofman2004, Reference Boomert, Hofman and Duijvenbode2011; Bright Reference Bright2011; Hofman, Hoogland, et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Jacobson, Manem, Boomert, Cristiana Barreto, Lima, Rostain and Hofman2021).

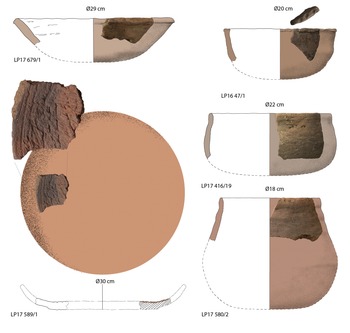

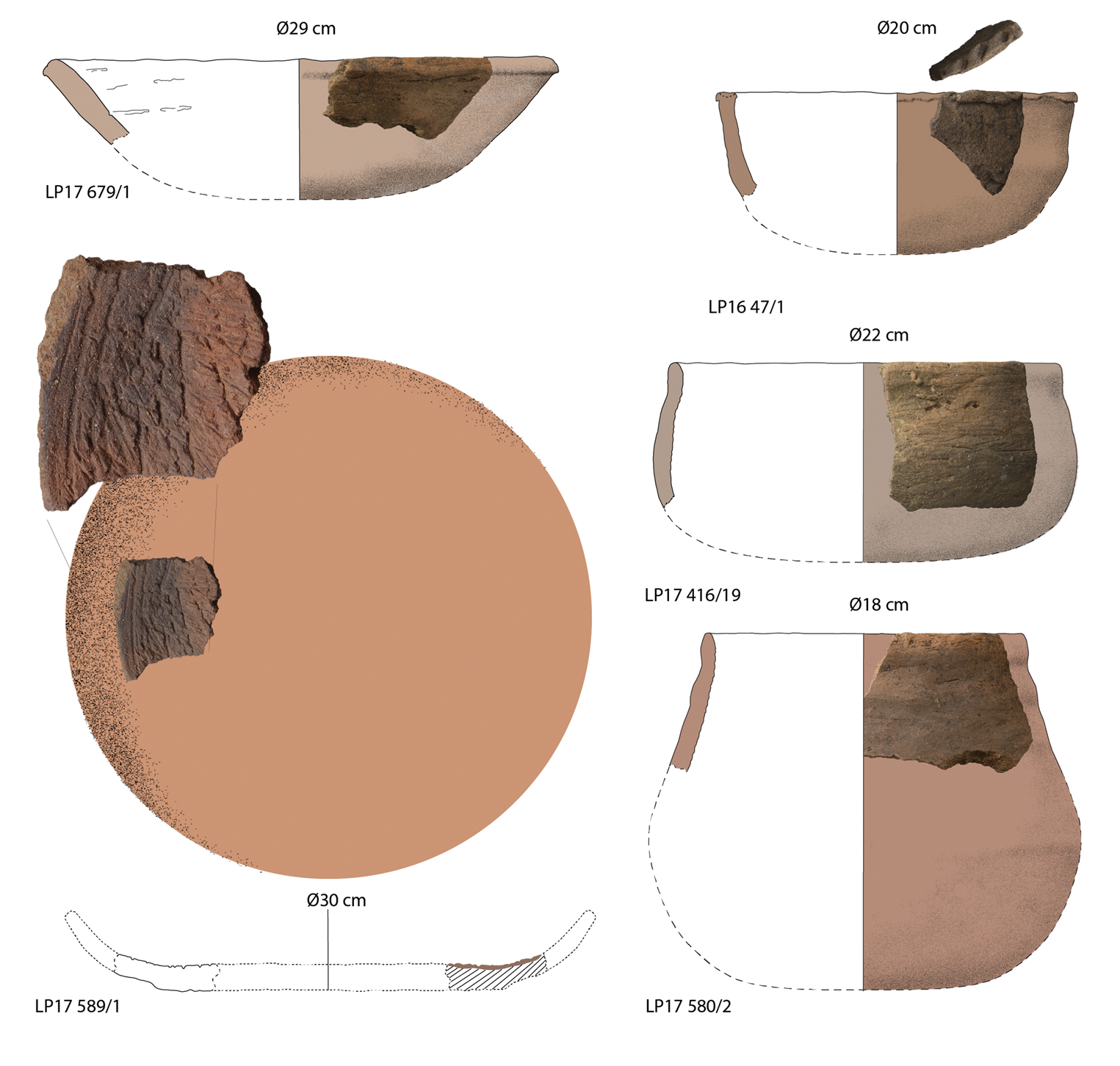

Suazoid pottery (AD 1100–1500) clearly reflects a local development from the previous so-called Troumassoid series of ceramic styles in the Windward Islands (Rouse Reference Rouse1992). The Suazoid series appears somewhere around AD 1100 and is suggested to end with the colonial period. But. in fact, its end date is virtually unknown, and it may well have continued into the early colonial period (Hofman and Bright Reference Hofman and Bright2004). In archaeological surveys late Suazoid pottery is often very difficult to distinguish from present-day Afro-Caribbean or folk pottery (Figure 2; see also Hofman and Bright Reference Hofman and Bright2004).

Figure 2. Suazoid pottery from the Windward Islands (figure and photos by Menno L. P. Hoogland). (Color online)

The Suazoid potters used forming techniques such as coiling and molding that were applied not only independently from each other but also in combination, depending on the size and shape of the intended vessel. Ceramic or calabash molds were probably used for this purpose. Scraping of the vessel wall was done with a shell or calabash sherd, and many utilitarian vessels have rather thick walls and a clumsy appearance. Most are crudely finished and show scratched surfaces. These scratches are the result of rubbing the surface with grasses when the clay was in a wet condition. In addition to purely domestic pottery, especially during early Suazoid times, a fine ceremonial ware often with polychrome painted designs was manufactured. Vessels were fired in an open fire in a controlled way, oxidizing to neutral conditions at low temperatures. The fire was built up as an open structure so the wind could blow through. Vessels were placed upside down in the fire to obtain a more equal spread of the heat (Hofman and Bright Reference Hofman and Bright2004).

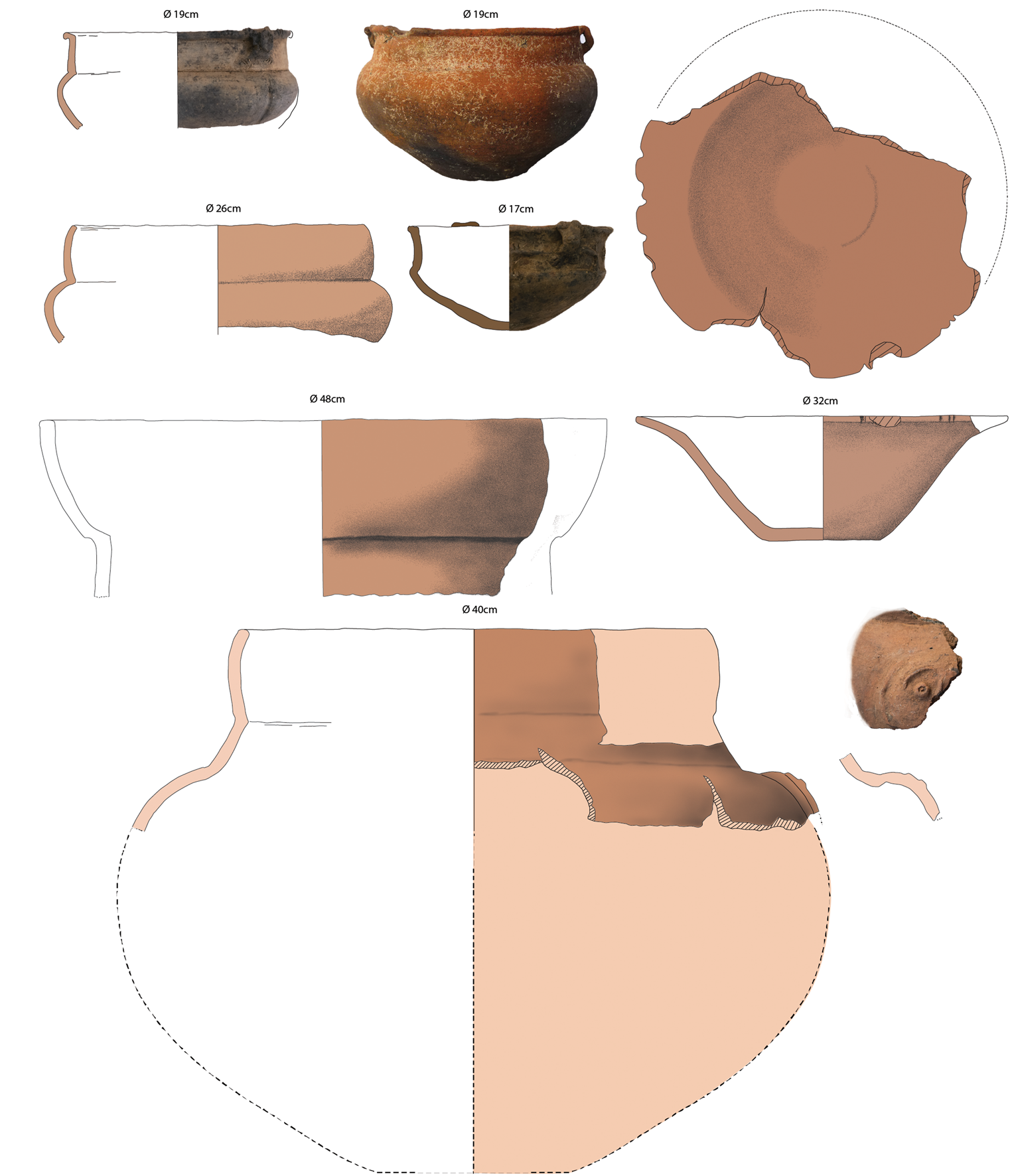

Cayoid pottery (AD 1450–1620) is clearly an interweaving of local Windward Islands and Greater Antillean (Meillacoid/Chicoid) and mainland (Koriabo) traditions (Figure 3; see also Boomert Reference Boomert1986, Reference Boomert and Whitehead1995; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019): it represents an outstanding example of a ceramic complex created by the process of creolization. A large variety of vessel shapes show modeled zoomorphic decorations, incisions, punctuations, notched fillets, and painted surfaces. Characteristic of these vessels are wide-mouthed bowls (so-called flowerpots) with lobed (indented) rims. Many have white-slipped interior surfaces, showing red, yellow, or black painted designs. These typical Koriabo bowls are known from the Guianas and as far as northern Brazil (Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Lima, Rostain and Hofman2021). On the mainland they often show fine-line red- and black-painted motifs on white-slipped surfaces. Large, restricted jars with strongly corrugated inner surfaces are similarly characteristic; these most likely functioned as containers for cassava beer (ouicou/cachiri), also mentioned by early seventeenth-century chroniclers as the ouchou. Some have modeled anthropo-zoomorphic decorations identical to those of mainland Koriabo vessels (Rostain and Versteeg Reference Rostain, Versteeg, Delpuech and Hofman2004). In contrast, various elaborately modeled-incised ornamental designs and some vessel shapes reflect direct influence from the Chicoid/Meillacoid ceramics of the Greater Antilles (Hofman, Hoogland, et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Jacobson, Manem, Boomert, Cristiana Barreto, Lima, Rostain and Hofman2021). Most likely they show the influx of people from the Greater Antilles (Hispaniola, Puerto Rico) into Island Carib society in the Lesser Antilles. This influx may have occurred because of the historically attested Kalinago/Kalipuna raiding of these islands or the flight of Indigenous people from the Greater Antilles into the Lesser Antilles due to Spanish pressure in the sixteenth century, especially after the 1511 Indigenous rebellion in Puerto Rico. Clearly, all this reflects the composite origin of the Island Carib/Kalinago/Kalipuna ceramic complex.

Figure 3. Cayoid pottery from the Windward Islands (figure and photos by Menno L. P. Hoogland). (Color online)

Generally, there are notable variations in coiling techniques, including coiling by pinching and spreading. Surface finishing and decoration techniques also show some variability. XRF and petrographic analyses have shown that 99% of the Cayoid pottery was locally made, confirming its production by communities that had moved to the Windward Islands, fusing their ancestral traditions with local ones (Hofman, Borck, et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Jacobson, Manem, Boomert, Cristiana Barreto, Lima, Rostain and Hofman2021). The painted “flowerpots,” which are tempered with caraipé (the burnt bark of a small savanna tree, Licania apetala), are the only exception. This temper material may have been brought in from the mainland (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Neyt, Hofman and Degryse2018).

The Mayoid ceramics of Trinidad that appear around the time of colonization and the contemporary Kalina pottery of the Guianas are also tempered with caraipé (Boomert Reference Boomert2016; Boomert et al. Reference Boomert, Faber-Morse and Rouse2013; Stienaers et al. Reference Stienaers, Neyt, Hofman and Degryse2020). Mayoid pottery is known from Trinidad's first Spanish capital San José de Oruña (the present-day St. Joseph, founded in 1592) and various seventeenth- to eighteenth-century Spanish-Indigenous mission sites. It is typified by nine, relatively thin-walled vessel shapes, including open and restricted bowls, bottles, and sizable cassava-beer brewing jars. Jars with sharply everted necks, resembling the nineteenth-century Arawak (Lokono) “buck-pots” of the Guianas, are most characteristic. Another Mayoid necked vessel is nearly identical to the Cayoid necked jar. Decoration is rare, although a few vessels are monochrome red painted; others show narrow black zones along the vessel rims. Oval, undecorated, punctuated, or nicked wall and rim knobs are most popular (Boomert Reference Boomert1986; Boomert et al. Reference Boomert, Faber-Morse and Rouse2013).

European trade wares (sixteenth to early seventeenth centuries) first appear in the Cayoid context when the Kalinago/Kalipuna strongholds participated in a complex transatlantic system that combined new colonial and trade strategies with preexisting Indigenous exchange and alliance networks (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Mol, Hoogland and Rojas2014, Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019). Most of this trade took place with Spanish ships or along the coast of the Guianas, where the Dutch had settled since the early 1600s. Goods imported from Europe (Spain, Portugal, Holland, France, and England) were exchanged for foodstuffs, tobacco, cotton, turtle carapaces, hammocks, and Indigenous ornaments made of a gold-copper alloy (kalikulis). Iron implements—including nails, knives, needles, hooks, bills, sickles, hoes, hatchets, saws, and griddles—were in great demand among the Island Carib, as were adornments such as colored glass beads, trinkets, mirrors, and combs. In addition, spirits and, rarely, firearms were traded (Boomert Reference Boomert2002, Reference Boomert2016). All these items were integrated into the Indigenous material repertoire and sometimes within one single object. An example of the latter is an Indigenous vessel inlaid with European seed beads found on an eroded cliff at the Cayoid settlement site of Argyle, Saint Vincent (Allaire Reference Allaire1994; Hofman and Hoogland Reference Hofman and Hoogland2012). Toward the end of the sixteenth century, iron nails and hatchets had in fact become indispensable to the Island Carib for the construction of their canoes, and vessels stranded in the Windwards were invariably stripped of nails for this purpose. The peaceful trade, especially with the nations of northwestern Europe, ended in the 1620s when they established plantation colonies based on the cultivation of tobacco in the Lesser Antilles. The site of La Soye 2 in Dominica is evidence of a very early trading post in which Cayoid pottery occurs in a European context (Hauser et al. Reference Hauser, Armstrong, Wallman, Kelly and Honychurch2019).

Afro-Indigenous or Afro-Caribbean Pottery

Seventeenth to Early Eighteenth Centuries

Beginning in the 1620s when the first English, French, and Dutch planters settled in the Windward Islands and introduced European earthenware, Indigenous and African intercultural dynamics led to the development of another creole ware, in which Indigenous manufacturing techniques were sometimes combined with African vessel shapes and finishing techniques. The recent development of very detailed analyses of the chaîne opératoire according to a homogeneous observation procedure allows better understanding of the similarities and differences between ceramic assemblages from the settlement site of La Poterie on Grenada. At this site the ceramic material was found in the habitation area among a dense palimpsest of postholes. These features belong to a succession of structures dating between AD 600 and 1620, corresponding with Troumassoid, Suazoid, Cayoid, and Afro-Indigenous or Afro-Caribbean pottery (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019; Hofman, Borck, et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Jacobson, Manem, Boomert, Cristiana Barreto, Lima, Rostain and Hofman2021).

The chaîne opératoire shows continuity in the Suazoid and Cayoid ceramic manufacturing techniques, the selection of clay sources and temper materials, and use of the coiling technique. However, clear changes are apparent in vessel forms, techniques of decoration, and surface finishing (Figure 4). The most interesting changes between the Cayoid and Afro-Indigenous traditions at La Poterie are probably in shaping, because of the strong identity character of Afro-Indigenous pottery and the distinguishing of social groups through their technical traditions (Roux Reference Roux2019); in addition, forming techniques appear to be more resistant to change than other traits such as morphology and decoration (Manem Reference Manem2020; Roux Reference Roux2019).

Figure 4. Afro-Indigenous pottery from the site of La Poterie, Grenada (figure and photos by Menno L. P. Hoogland). (Color online)

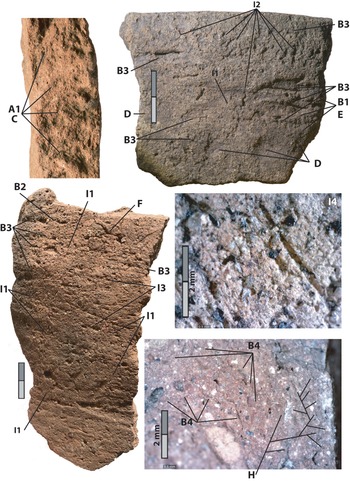

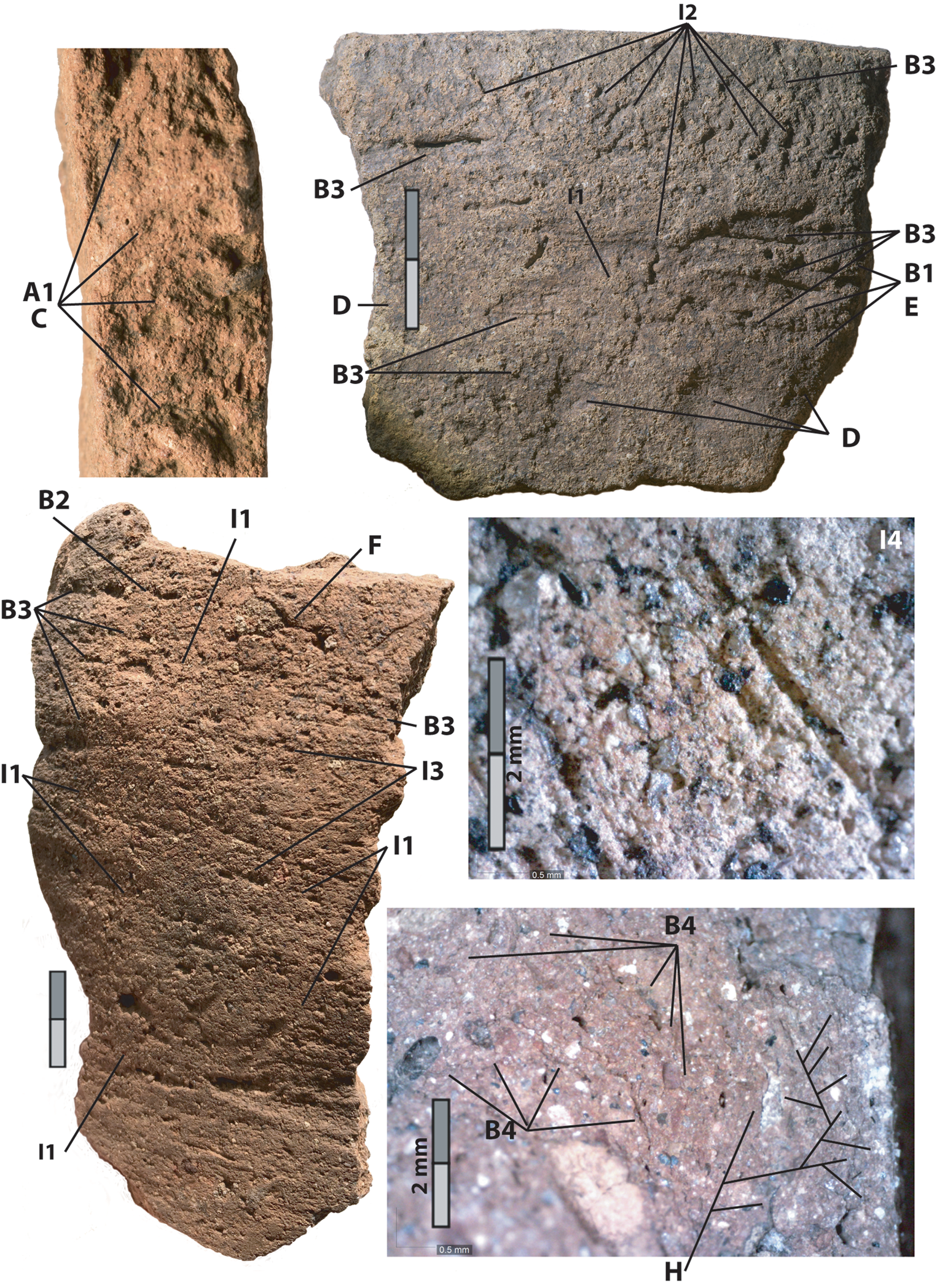

A brief description of an Afro-Indigenous sherd from La Poterie, which only includes a vessel body and neck due to fragmentation, shows this difference from the Indigenous wares discussed earlier. The roughout was obtained from a heterogeneous elementary volume by which coils were made by pinching (Figure 5). The procedure for making coils seems to be a segment procedure with small segments or, in other cases, long segments. The junction between each assembled element is made by a semicircular (U-shaped) joining. Therefore, the coils are superimposed. The preform was obtained on leather-hard paste by shaving the clay using horizontal movements (see Supplemental Text 1 and Supplemental Figure 1 for diagnostic features and a detailed description). The main difference between the Cayoid and Afro-Indigenous ceramic traditions is currently visible in the preforming techniques (see Hofman, Borck, et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Jacobson, Manem, Boomert, Cristiana Barreto, Lima, Rostain and Hofman2021; Hofman, Hoogland, et al. Reference Corinne L., Borck, Laffoon, Slayton, Scott, Breukel, Falci, Favre and Hoogland2021:Figure 6). The preforming was achieved on wet clay by scraping in Cayoid pottery and on a leather-hard clay in Afro-Indigenous ceramics. These differences in ceramic technical traditions clearly indicate the presence of two social groups in La Poterie, as a result of the migration of a new group. A Suazoid sherd from a midden deposit of the settlement site of Giraudy on Saint Lucia seems to illustrate this diversity of technical traditions and social groups but with a certain proximity to Cayoid and Afro-Indigenous pottery from Grenada (see Supplemental Text 1 and Supplemental Figure 2 for diagnostic features and a detailed description). The roughing out—coiling by pinching—is similar to that of the Afro-Indigenous sherd, and the preforming, by scraping, is also a visible technique in Cayoid sherds of La Poterie. However, there are differences between these three cases. In contrast to the Afro-Indigenous and Cayoid sherds from Grenada, the Saint Lucia coils are not prepared beforehand by a revolving movement. The operating procedures for the junction between each coil are also different for the Saint Lucia sherd, which has a bevel joining. Our forthcoming cross-site analysis will allow us to better understand the similarities and differences among these three cases.

Figure 5. Afro-Indigenous ceramic tradition: roughing out by coiling technique, by pinching (a1 to f) and preforming on leather-hard paste by shaving (h and i). Diagnostics features: (a1) discontinuity, (b1) rhythmic and horizontal undulations, (b2) over-thicknesses, (b3) horizontal and equidistant fissures, (b4) relic coils on fresh section, (c) U-shape, (d) discontinuous pressures, (e) undulations on both surfaces confirming the absence of support, (f) joint between two ends of coils, (h) laminar fissuring subparallel to the wall visible fresh section, (i1–i6) crevices, compact microtopography with inserted grains, erratic striations and horizontal secant planes (see full descriptions in Supplemental Text 1; photos by Sébastien Manem). (Color online)

Contemporary Potters at Pointe Caraïbe and Morne Sion, Saint Lucia

Indigenous–African–European intercultural dynamics are still mirrored in today's locally produced creole pottery in the Lesser Antilles, such as that of southern Saint Lucia (Pointe Caraïbe, Morne Sion, Delcer, Industrie, and Martin; Fay Reference Fay2017). Most vessels produced in these villages have French Creole names. The kanawi (Fr. canari) or cooking pot is the most popular vessel type on the island today. It resembles the Island Carib canalli described by the early chroniclers of the seventeenth century. The kanawi is a vessel with a simple contour and a handle at opposite ends. The dimensions of this vessel vary from small to very large and are also associated with the lid couvèti kanawi (Fr. couvercle de canari). For cooking, these pots are placed on three stones called fouyé (Fr. foyer). The tèson or coal pot is an outward-flaring vessel, sometimes with finger indentations on the rim, and is wider at the top than at the bottom. A perforated base separates the top from the bottom, which has an opening for the placement of fuel. The chòdyè (Fr. chaudière) is a large, flat-shaped vessel for frying. This flat-shaped pot is placed on top of the coal pot. Then there is the téyè, the teapot; the pòt a flè (Fr. pot à fleur), the flowerpot the jar (Fr. jarre), a water container the pla (Fr. plat) to put food on at meals, and the téwin (Fr. terrine) showing two loop handles, used for washing, cooking food, or to as a water container. Finally, there is the platin (Fr. platine), a very large plate to bake cassava bread, which is also recognizable from the Indigenous repertoire (Figure 6; see also Hofman and Bright Reference Hofman and Bright2004).

Figure 6. Afro-Caribbean pottery from Morne Sion, Saint Lucia: (A) coal pot, (B) pla, pòt a flè, (C) chòdyè, couvèti, (D) Gwan kanawi, (E) téyè, (F) Gwan kanawi, (G) Kanawi (photo by Corinne L. Hofman). (Color online)

The pottery tends to be heavy and coarse. The mineralogical content of the paste is similar to that used in Suazoid and Cayoid pottery. The clay derives from the immediate environs of the potter's workshed, the place known to hold the best-quality clay. It is used as such or sometimes with temper “tè blan” or “tè roug” (white or red clay). Coiling and modeling are used, rather than wheel manufacture. Decoration is rare, but the finger-notched or finger-indented patterns on rims are very similar to those on Suazoid ceramics. Firing is done very quickly and in an open fire where the clay pots are piled up and covered with branches, which is also very similar to what is assumed for the firing of Suazoid and Cayoid pottery.

Discussion and Concluding Note

Today, the Caribbean is celebrated because of its diverse and multicultural societies that have developed over the last five centuries. What created these diverse societies, however, was a painful and difficult process defined as creolization stemming from the European invasion of the Americas after 1492, followed by the colonization, destruction, and neglect of its Indigenous populations and the introduction and exploitation of enslaved Africans and indentured Europeans as part of the colonial enterprise. These creole societies are regarded as distinct in the way they were created under the dominance of Europeans over diverse peoples, often through violence; yet they were not culturally representative of any of the individual groups but of all of them (Brathwaite Reference Brathwaite1971; Glissant Reference Glissant1997, Reference Glissant2008; Palmié Reference Palmié2006; Mintz and Price Reference Mintz and Price1976). This process of cultural change was a dynamic one that created societies that were new to the archipelago and differed from each other, as reflected in their overall cultures, with new languages, religious practices, music, rhythms, foods, architecture, dress, and even the people themselves. The Caribbean and its new societies came to represent the multi-loci process of cultural change established on an Indigenous landscape by multiple European colonial enterprises using enslaved Africans yet showing how each contributed to the formation of these distinctive societies.

In this article we highlighted the divergent origins and developmental trajectories in pottery tradition in the Windward islands of the Lesser Antilles from the time before European colonization until today, suggesting that creolization, as proposed earlier by Curet (Reference Antonio and Hauser2011) and Kahn (Reference Khan, Palmié and Scarano2011), forms the central concept through which these processes of cultural interaction can be understood. We argue that the chaîne opératoire of pottery manufacture is yet another lens through which creolization can be visualized. It is also essential not to underestimate other processes responsible for the evolutionary trajectories of technical traditions; for example, a chaîne opératoire may be modified to produce a new ceramic shape to meet new functional needs of consumers, while other social groups will adopt (or not) the same vessel without modifying their tradition or will do in an even different way. The number of carriers of a technical tradition and thus the size of the transmission network (restricted to a few potters or a large number) will be affected if the social group is mixed with a new one that may or may not be a carrier of another technical tradition. Therefore, our perception of creolization will not be the same from one context to another, and this process will not necessarily affect material culture in a homogeneous way. Thus, creolization may affect only visible traits of the material culture (form or decoration, interaction between consumers), whereas in other cases borrowing processes will modify the technical tradition (interaction between producers).

Suazoid pottery represents an Indigenous tradition of the Lesser Antilles that probably partially carried on into the period after European colonization. Cayoid pottery is a development that started in the late fourteenth to fifteenth centuries and continued until the early seventeenth century, reflecting the processes of population movement into the Lesser Antilles and the formation of a new Kalinago/Kalipuna identity. The Afro-Indigenous pottery identified at La Poterie is a first reflection of very early Indigenous–African interaction in the Windward Islands. Finally, present-day Afro-Caribbean pottery clearly has its roots in West Africa but is also the result of a creolization process involving Indigenous, European, and African traditions. The disruption of the Indigenous cultures, the impact of European colonization, the African diaspora, and the movement of indentured laborers from various parts of the globe to the region have led to the emergence of today's complex cosmopolitan Caribbean cultural tradition. The spheres or lines of social interaction among communities from different parts of the world cemented a regional history marked by differential responses to the colonial incursion in which coexistence, interaction, and transculturation were fundamental in the shaping of modern creole society.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results received funding from the European Research Council for the project Nexus 1492 (ERC grant no. 319209), the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO Open Competition grant no. 360-62-060) as part of the research program Island Networks; and NWO-CaribTrails. A first version of this article was presented at the 83rd Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in 2018, in Washington, DC, in the symposium “Material Culture and Multivocal Cultural Dialogue in the Construction of the Criollo Universe in the Caribbean,” organized by Antonio Curet and Jorge Ulloa Hung. We thank Loe Jacobs, Becki Scott, Anneleen Stienaers, and Patrick Degryse for sharing their insights and knowledge on the fabric and mineral composition of the studied clays and ceramics. We would especially like to acknowledge the community of La Poterie, Grenada; the Kalinago and Garifuna communities in Dominica and Saint Vincent; and the community of potters in Morne Sion, Saint Lucia, for their participation, co-creation, knowledge exchange, and collaboration in the various research projects.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not yet openly accessible.

Supplemental Materials

For supplemental text and figures accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2021.102.

Supplemental Text 1. Description of the chaîne opératoire of ceramic traditions from Grenada and Saint Lucia.

Supplemental Figure 1. Ceramic chaîne opératoire of an Afro-Indigenous or Afro-Caribbean sherd, Grenada.

Supplemental Figure 2. Ceramic chaîne opératoire of a Suazoid sherd, Saint Lucia, Giraudy.