The passage from pre-modern to modern is always understood as a rupture and separation, whether of a rational self from a disenchanted world, of producers from their means of production, or of nature and population from the processes of technological control and social planning. Each of these so-called ruptures is a way of accounting for a world increasingly staged according to the schema of object and subject, process and plan, real and representation.

— Timothy Mitchell (Reference Mitchell2000, 18)Today a growing body of spatially conceptualized scholarship focuses on state commemorations, transportation, and urban infrastructure in colonial Korea.Footnote 1 As a counterpoint to this research on public spaces, this reading will draw from The Heartless (Mujŏng, 1917),Footnote 2 modern Korea's first “novel” and its most studied text, to emplot colonial identity onto the private, less visible places in colonial Seoul (Keijō) and the larger Japanese empire. Certeau (Reference Certeau1984) and Lefebvre (Reference Lefebvre and Nickelson-Smith1991) have observed in their influential writings on space that the processes of individual actors “from below” are sometimes uncharted, or do not cohere with master plans, as people on the ground always diverge from maps to maneuver or resist. Collaborating with social and architectural historians, I have become increasingly convinced that literature is also an ideal site for excavating the everyday processes of the disenfranchised whose practices were hidden from official view. This was often the case for the colonized who did not wish to be legible in official maps and government plans, or become coerced and coopted into public assimilation projects (Scott Reference Scott1998).Footnote 3 Literary works depict local everyday practices in winding and rundown alleys, family homes, boarding houses, female entertainer (kisaeng) quarters, and other quotidian places of the old capital, and not so much in glittering department stores, exhibitions, and main boulevards, thus supporting the characterization of Seoul as a segregated “dual-city” whose unevenness invited yet defied assimilation (Kim Baek Yung Reference Yung2009, Reference Yung and Chongyŏn2012; Uchida Reference Uchida2011).Footnote 4

Yi Kwangsu, author of The Heartless, was colonial Korea's most famous writer, nationalist, and modernizer, yet its most problematic historical figure following his collaboration with the Japanese from 1939 on (Im Reference Chongguk1963; Treat Reference Treat2012; Yi Kyŏnghun Reference Kyŏnghun1998).Footnote 5 He was also a celebrated travel writer whose observations on trips spanning some fifty years of early twentieth-century East Asian history shed important light on the colonial subject's positionality within the empire. Contrary to his prominence in the Korean literary sphere and his much-studied complicity with the Japanese, because Yi was colonized elite in the larger expanse of the Japanese empire, he was rendered invisible in Tokyo. Much of Yi Kwangsu's lifelong cultural and political anxieties stemmed from his belief that he was from a “backward” homeland not yet as modern as the glittering Tokyo of his formative school years.

Set against this cultural backdrop, The Heartless depicts a transitioning Seoul of Modern Boys and New Women exploring free love as a metaphor for enlightened modernity, the object of colonial desire itself. This is because “love for Yi Kwangsu was not just a simple lyrical motif or symbol, but operated at the level of a world view or ideology” (Seo Reference Yongchae2004, 9). As Korea's first modern novel, The Heartless was selected for inclusion in Franco Moretti's (Reference Moretti2006) world literature anthology, The Novel, as representing the universal (deterritorialized) trope of youth coming of age in a modernizing landscape, and located transnationally with parallel texts, from Futabatei Shimei's The Floating Cloud (Ukigumo, 1886) in Japan, to Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart (1958) from Nigeria (Field Reference Field and Moretti2006; Jongyon Hwang Reference Jongyon2005, Reference Jongyon and Moretti2006; Julien Reference Julien and Moretti2006). It has been celebrated for its “forward-moving drive of modernization and its reliance on the nation for ethical and narrative closure” (Poole Reference Poole2014, 40–41). Extant studies on this seminal literary work are too numerous to cite here, but most scholarship to date on The Heartless likewise focuses either on the text's significance as an early modern literary form or on the above depictions of new subjectivity, values, romance, education, and even fashion reflecting the zeitgeist of modern “civilization and enlightenment” (munmyŏng kyehwa) (J. Shin Reference Shin2004; M. Shin Reference Shin, Shin and Robinson1999).

Yi's influential early writings on the minjok (ethnic nation, J. minzoku) include not just his fiction but a body of essays and voluminous travelogues, which reintroduced an old king-centered Chosŏn society (1392–1910) as a modern ethnic nation-within-empire to a very small but increasingly literate colonial readership.Footnote 6 In 1916, young Yi Kwangsu himself described the modernization he observed during his travels as an unstemmable, universalizing force that organized individuals, labor, communication, movement, education, and even leisure into rationalized forms circulating rapidly through an intimidating new world order. This modern, capitalist sphere dominated by industry and power sustained itself through the repetitions of railways, factories, telephones, and sewing machines clacking “busily” towards the future, and operated along a temporal trajectory Yi felt most Koreans were oblivious to (“One minute, one second of a Thomas Edison's time is more valuable than a hundred, or several hundred years for a powerless ethnic minjok”; Yi Kwangsu [Reference Kwangsu1916] 1963b, 487). Yi conceptualized time as functioning differently in “awakened” civilized and “sleeping” backward spaces, configuring an affect of temporal difference that was experienced as a “rupture” from the Korean self and the Western (Japanese), modern Other. Contact with the West and modernity was felt even more violently when introduced through a colonial mechanism involving the inevitable loss of both cultural and political authority (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2000).

Yi Kwangsu's novel was more than a pioneering work showcasing modern enlightenment and social mores to the colonial imagination, however. Despite the text's much noted celebration of the new, The Heartless was an equally compelling testament to what had been forgotten and lost in that very rigorous march to attain modernity, not just in the writer's colonial imagination, but also in the field of “Yi Kwangsu studies,” which has become an industry in itself in Korea. The travelogues from his 1916–17 period therefore frame The Heartless as a series of interconnected moments on one collective map that recast the writer's socio-historical identity at personal and communal levels against a shifting global empire. The colonial Keijō (Seoul) mapped in The Heartless was the novelistic dream for a Korean minjok, and the location of a new “national” identity in all its subsuming power, but one that had not yet actually been realized. Despite the modernity (subject formation, education, technology, fashion) portrayed in Yi's novel of Seoul, his travelogues ironically depict Korea itself in the 1910s as a “dead” space, with an incomplete modernity, and one that would need to be reconstructed and rigorously redrawn to become a space for the nation.Footnote 7

Korea's decrepit state comes into clearer view with the sun's ascent. Look at the naked mountains.… Worn with long drought like a girl raised by a stepmom, the grass and even the trees look so pathetic that I can't bear it.… I'm also sure that the bare mountains will one day be covered with thick, lustrous forests, and that the dried-up streams will overflow with clear water.… Slowly, gradually, draw up something glorious and long-lasting. (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917c, episode 11; emphasis added)Footnote 8

The young modernizers here returning to Pusan on the Shimonoseki (KanFu) ferry from study abroad in Tokyo experienced the task of “drawing up” the minjok as a “rupture, a separation” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2000) from their origins and pasts, and a project requiring resolution and heartlessness: “Little brother (tongsaeng), please don't call me heartless (mujŏng). Of course, I want to stay and comfort you, but we aren't people driven by our emotions. Our goals mean we're to be separated by great distances, shedding tears…” (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917c, episode 1).

Positioned thus in between Korea and the Japanese empire, Yi dedicated himself to the “goal” of civilization, claiming to know and speak for the Korean minjok, but his elite Waseda University education complicated his position and alienated him from the people (Chosŏn saram). Yi's ideas on the primacy of an organic minjok over other collective identities, and his translation of the concept of nation into Chosŏn, stemmed from this in-between position co-figuring Korea and Japan, which, in turn mimicked Japanese thinkers’ own in-betweenness with the East and West (Sakai Reference Sakai2006). Yi Kwangsu translated modernity and national consciousness from this representative in-between position to an actual lived place, a place that I show was essentially incommensurate with the new vision of Korean minjok adopted by the international student during his travels. This ideal future for Korea came to be drawn up in The Heartless, which depicted self-awakened young people melding their individual desires into that of this new collective national identity. The novel helped forge a topographical imaginary of that nation from a field of contested claims.

English-language studies on travel to date tend to focus more on the colonial aspect of imperial space, not giving equal voice to local processes,Footnote 9 because the centralizing discourses of modern empire-building (and simultaneous nation-building) sublimated other memories and localities. My reading by contrast will complicate extant scholarship on Yi's novel, which focuses only on the forward-looking face of modernity in The Heartless. The minjok projected through the novel is read as a simulation of how “Korea” was to be, and not how it actually was, leading us to uncover through the city of Seoul both the visible and the veiled layers of space and time made possible by Yi's literary representation of the urban landscape. The question posed by Homi Bhabha ([Reference Bhabha1994] 2006, 139–70)—“What is the ‘now’ of modernity?”—is particularly germane here, reminding us that the “modernity” we isolate in interpreting these transitional literary forms testifies more to a desire for a culturally constructed futurity (the Korean minjok), rather than the “now” in its unrepresentable multiplicity. I similarly take issue with the representational claims of modern temporality figured in the novel—what I call the dream of a future minjok (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2000). My reading is thus postcolonial in its challenging of assumptions about capitalist, modern time as a universal one, and its questioning of the tendency to over-emphasize “modernity” and development, which, this article suggests, is conducted at the cost of forgetting what was relinquished in that same long march towards progress.

Although the protagonists in The Heartless are depicted resolutely marching towards the “national” time of the new nation, I suggest that their hearts and minds are in the north, not in Seoul nor in Japan. There were other temporalities co-existing with the more dominant modern (national) times that arrived through a universalizing, colonial mechanism. By delineating the protagonists’ peregrinations in and around the north, I show that the “now” depicted in The Heartless involved multiple spatio-temporalities and that Yi Kwangsu was more ambivalent about Korea's past, tradition, and the local than previous scholarship on the author had suggested.

Forgotten people, as well as faraway places, add spatial and temporal strata to the imperial-national binary of the represented colonial city, cocooned in the mnemonic landscapes of colonial writers who were living far away from their actual hometowns. Other (Foucault [Reference Foucault and Miskowiec1967] 1984, 4) places existed under the Korea-Japan axis of the visible colonial modern, for even though Yi would become a representative Seoulite, his home (古鄕 kohyang, furusato) was Chŏngju, near the gendered (Massey Reference Massey1994) northern capital of P'yŏngyang, a faraway place in South Korean popular memory and in extant studies on Yi Kwangsu.Footnote 10 The unidirectional thrust of global capitalism put modern identity at odds with the fact that individuals such as Yi Kwangsu identified with a plurality of often contradictory spatio-temporalities. The Heartless shows Yi Kwangsu's positionality as complicated by an embodied condition of alterity (Otherness within the self), wherein registers of belonging were not only Tokyo and Seoul, but also remote hometowns.Footnote 11

Departures (Sanggyŏng 上京) and Returns (Kwihyang 歸鄕)

Yi Kwangsu is criticized in Korean politics as having belonged to the bourgeois elite, neither entirely disenfranchised nor invisible in Seoul. While acknowledging Yi Kwangsu's place as colonial elite, I will attempt to configure through the forgotten practices of past selves and faraway places those processes that were less legible to both nationalist and colonial readings and in the official state maps. The juxtaposition of minjok and empire was mapped onto the colonial city (Keijō in Japanese; Hanyang/Hansŏng in old Korean), but served to veil these local memories. Thus, Yi's early position in the Japanese empire can be understood through The Heartless’s semi-autobiographical male protagonist, Yi Hyŏngsik, who is depicted moving repeatedly between Seoul and Tokyo, and, as I will demonstrate more significantly here, between Seoul and the distant northern P'yŏngan Province, his local hometown region.

Against the expanding spatial axes of the colonized imagination (in this case, moving away from his hometown area of Chŏngju to P'yŏngyang to Seoul to Tokyo and finally to the “West”), the reality was that in the larger empire, Yi belonged to the colonial “lumpen” (Choi Reference Choi2009). Yi Kwangsu wrote The Heartless from Tokyo, where international students were displaced without a place at home or at work.Footnote 12 Back home, the student's position towards less-educated countrymen became pedagogical insofar as Yi constantly placed expectations adopted in Tokyo on Korea. The colonial elite's “location of culture” (Bhabha [Reference Bhabha1994] 2006), which contained his anxiety-inducing registers of modern cultural referentiality, remained the imperial metropole, Tokyo. This meant that the international student was as dislocated back “home” in Seoul as he had been in the intimidating classrooms and bustling streets of Tokyo.

This problematic position between Japan/West and Korea was negotiated by thinkers like Yi Kwangsu through what Naoki Sakai (Reference Sakai2006, 74) calls a “regime of translation,” which was a universalizing schema from which Japanese intellectuals had translated the nineteenth-century concept of the nation as the neologism “minzoku” during the Meiji period. Korean cultural nationalists, many of whom, like Yi Kwangsu, had been international students in Tokyo, similarly translated the idea of nation into Korea as the minjok ethnie. Yi's vision of minjok is translated through the development (Bildung) of Yi Hyŏngsik, the protagonist of the story, as he moves across the east-west Chongno Street axis of the “dual-city” of colonial Seoul, travels north to P'yŏngyang, and doub les back to the imperial metropole of Tokyo (Anderson Reference Anderson1998; Harootunian Reference Harootunian2000a, Reference Harootunian2000b). Thus through the translative processes of departures and returns, the early works of Yi Kwangsu allowed the Korean readership to experience minjok identity, insofar as travel instilled self-awareness and brought colonial difference into greater relief within the physical contours of a new national imaginary (Hong Reference Kal2005).

In 1903, Yi Kwangsu left Chŏngju (a small city outside of P'yŏngyang) at the age of eleven and “went up” to P'yŏngyang, which was a northern regional capital.Footnote 13 He then “went up” to the capital of Seoul (Keijō), and finally, to Tokyo, the imperial metropole in 1905, as an international student. In keeping with global migrations in the rapidly modernizing turn of the twentieth century, each leg of the journey signified Yi's entry into a larger cultural regime (regionalism → nationalism → empire → global cosmopolitanism; see figure 1). Yi would visit Tokyo many more times during the colonial period and also dreamed about visiting the United States, even though he missed his opportunity when World War I broke out. Travel was important in such a layered context, in retroactively opening up through returns and memories the coeval (and heterotopic) spaces closed off by empire to forgotten narratives and stories. In mapping the repetitions of “going up” (上京 sanggyŏng; J. jōkyō) to regional centers, The Heartless simultaneously revisits the hometown in the north, portrayed with uncharacteristically warm, evocative feelings (chŏng) and nostalgia. Thus, postcolonial alterities embody both departures and returns, challenging the overarching focus on Western modernity historically identified with this seminal text.

Figure 1. This diagram captures the repetitions of “going up to the capital” in a universalizing sense, a socially upward move that eventually creates the conditions for global cosmopolitanism.

Tokyo and Seoul in the 1910s were marked by vast differences in social and educational policies governing young people (Caprio Reference Caprio2009; Uchida Reference Uchida2011).Footnote 14 The reality was that while colonial Korea was experiencing “the Dark Period” (“Amhŭkki” in Korean memory), Japan was buoyed by recent Meiji triumphs and experiencing the so-called era of Taishō (1912–26) “liberalism.” The diversity and range of intellectual and political ideas taught in top Japanese universities contributed to a spirit of “liberalism” that belied the conservative statism undergirding political praxis (J. S. Han Reference Han2007, Reference Han2013). This inconsistency was veiled in the metropole, but in the imperial peripheries the political lag between inner (naichi) and outer (gaichi) was explained as a problem of space and time. For colonial nationalists, the very act of travel was a negotiative process of trying to flatten this unevenness into a collective, redemptive future, where Korea would become as modern as Japan. Thus the project of minjok-building for cultural pioneers like Yi Kwangsu involved the rigorous projection of an imagined visual field of a future not yet built in the 1910s. The Heartless therefore captures a specific moment in Korean cultural history when the past, present, and future coevally dwell in a colonial subject's experience, revealed in the novel in flashbacks to the characters’ former selves, as well as in their visions of futurity. Reflecting this in literary form, the novel creates a colonial modern “world picture,” a “minjok-as-picture” that was yet to be, functioning like a cinematic work that cast modernized new citizens together “into a collective future” of a Korean minjok ideal not yet realized in the 1910s (Heidegger [Reference Heidegger, Young and Haynes1938] 2002, 57–85; Hughes Reference Hughes2012, 5; Mitchell Reference Mitchell1991, 7).Footnote 15

Yi Kwangsu was a second-year Waseda University student when he wrote The Heartless and had never really lived in Seoul. He had spent his childhood in northwestern Korea (Sŏbuk 西北)Footnote 16 where he was from, and had been abroad in Tokyo since his teenage years. He taught at the Osan School, again in northern Korea, before returning to Tokyo to resume his education in 1915. Except for short visits to Seoul during his school vacation, Yi was, during The Heartless’s composition, another modern transient in the capital, despite having been one of two colonial intellectuals, along with Ch'oe Namsŏn (1890–1957), dominating the 1910s student literary scene.

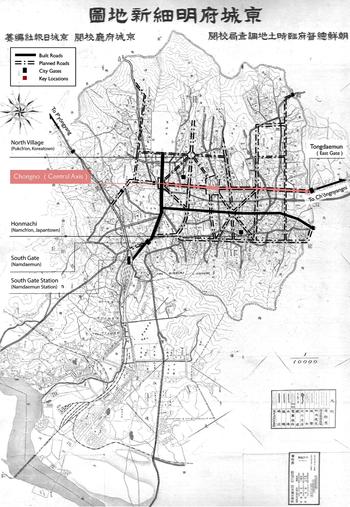

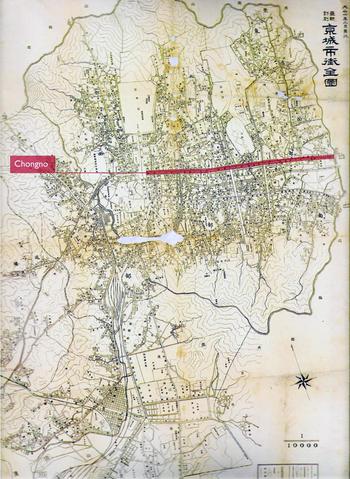

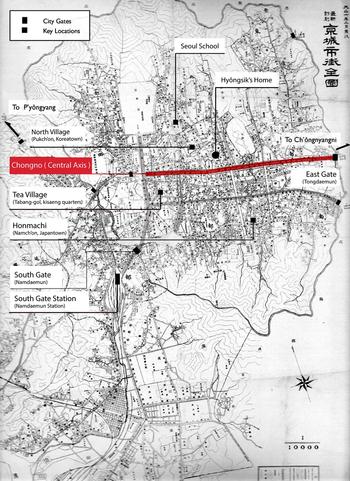

Movement and the act of walking discursively emplot national identity on the city's spatial grid, as railway travel within the larger empire (in this case, back to and returning from P'yŏngyang) creates the impetus for the protagonist's development into a rationalized subject conversant in both minjok nationalism and Tokyo modernity. The planned rationalization (Hausmannization) of the colonial city, captured here in the Government General's 1914 master plan for a better assimilated future Seoul/Keijō (see figure 2), along with the 1917 “after” map of the failed Hausmannization (see figure 3), testifies to the contentious transformation of old Hanyang (premodern Seoul) into a modern imperial-national city of Keijō (colonial Seoul). The winding alleys, which remained despite the state plans, spoke to the tenacity of residents who lived in both North Village (Pukch'on), the underdeveloped Korean residential area of the old city north of the dividing Chongno Street line, and Honmachi (Japantown or South Village), the Japanese settlement area to the south of that same main throughway. Colonial difference was often narrated in spatio-temporal terms through the city itself, where North Village was read as “backward” compared to the glittering spaces of the more modern Honmachi. Yet this confluence of spatio-temporality in colonial terms is not sufficient on its own to account for the complexities in time and space in The Heartless as a text that is more than colonial or modern. This configuration will be important for reconsidering Yi's significance in understanding the nation-within-empire and more deeply layered subjective alterities.

Figure 2. An ambitious 1914 master plan for “Hausmannization” of Seoul. Published with permission from the private collection of Yoon Daehyung of Bumsoosa Publishing. (Labels added by the author.)

Figure 3. A 1917 map of Seoul after failed Hausmannization. Published with permission from the private collection of Yoon Daehyung of Bumsoosa Publishing. (Labels and shaded line added by the author.)

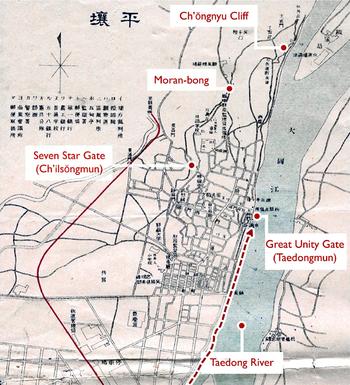

The novel's Yi Hyŏngsik is an inhabitant of North Village (Koreatown) in Seoul, north of the central Chongno Street, which separated the previously mentioned Korean and Japanese neighborhoods. He is a poor former international student without any social connections in Seoul and embodies the author as a young man, well before Yi Kwangsu became a prominent figure in the 1920s colonial sphere as the editor-in-chief of the Tonga Ilbo (East Asia Daily News). The imagined future is the modernizing city of Seoul, but strong evocative feelings are associated with northern Korea, especially with Hyŏngsik's (and Yi Kwangsu's) memories of coming to the regional capital of P'yŏngyang when he was a country bumpkin, an invisible local inhabitant entering through the forgotten Seven Star Gate (Ch'ilsŏngmun) of the ancient northern city. Homi Bhabha ([Reference Bhabha1994] 2006, 139–70) takes the postcolonial position in speaking about the metaphor of landscape as the “inscape” of national identity, stating that “[t]here is, however, always the distracting presence of another temporality that disturbs the contemporaneity of the national present.…” Taking my cue from Bhabha, I will reconsider the persistence of other temporalities that interrupted the minjok’s national time that serves as the narrative frame of the story. Country bumpkins in straw shoes and white clothes (like the author as a young boy) who have just arrived in Seoul existed coevally with Modern Boys and Girls living their national time. Most importantly, however, neither the country bumpkin nor the Modern Boy is privileged or celebrated over the other but together are considered an embodiment of alterity.

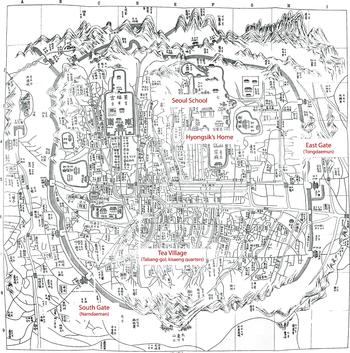

Hyŏngsik rents a room next to Pagoda Park (erected under King Kojong's reign in 1900 by McLeavy Brown),Footnote 17 within a short walking distance from the Seoul School in An(guk-)dong where he works, to the east of the central palace (Kyŏngbok) where the previous Chosŏn dynasty's court officials had once lived (see figure 4). He is a lonely bachelor whose rare personal connection to the city is through his sympathetic landlady who provides a modicum of maternal warmth with her rotten bean paste (toenjang) soup. Unlike the detailed, intimate portrayals of domestic spaces—for example in Natsume Sōseki's And Then (Sorekara, Reference Sōseki and Field1909) and Yŏm Sangsŏp's On the Eve of the Uprising (Mansejŏn, Reference Sangsŏp and Park1924)—with similar male university student protagonists, The Heartless’s urban landscapes reveal that Hyŏngsik is an outsider in Seoul, just as he had been in Tokyo as an international student.Footnote 18

Figure 4. Hyŏngsik's everyday life is mappable in locations that have existed since the Chosŏn dynasty era, as is shown in this 1900 map of Hanyang (Seoul). Published with permission from the Royal Asiatic Society of Korea. (Labels added by the author.)

Brilliant but also shy and indecisive, Hyŏngsik is torn between two women, Sŏnhyŏng and Yŏngch'ae, who have conventionally been interpreted as catalysts for his Bildung. From a wealthy Christian family, Sŏnhyŏng (born in Seoul) has graduated from a Western-style school and is planning to study in the United States. Yŏngch'ae (born in the north) is the daughter of Hyŏngsik's old mentor Scholar Pak from the P'yŏngyang area, who had died tragically while working for the Korean people. Hyŏngsik, also originally from the north, was separated from Yŏngch'ae by the social changes sweeping through Korea and has moved on, but Yŏngch'ae has remained devoted to Hyŏngsik, her childhood love. Though reunited in Seoul, Yŏngch'ae is soon heartbroken to find that Hyŏngsik's life no longer holds a place for her. Now celebrated in Seoul as the famous female entertainer (kisaeng), Kyewŏrhyang,Footnote 19 Yŏngch'ae is raped by profligates, and returns bereft to P'yŏngyang, leaving a suicide note declaring that she will “throw herself into the Taedong River.” Hyŏngsik follows after her, but ultimately gives up his search for Yŏngch'ae in P'yŏngyang and what she represents (tradition, Confucian loyalty), and chooses a life with Yŏngch'ae's Westernized foil, Sŏnhyŏng, who is depicted framed by a modernizing Seoul and the promise of study abroad in the United States (Kwak and No Reference Youngmi and No2007).Footnote 20

A Future City

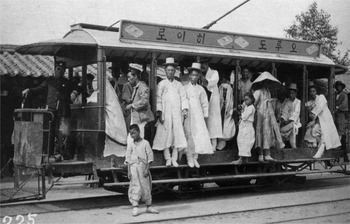

The city in The Heartless is a marvel, a literary simulation, a futuristic world picture maintained by an active but isolated interiority (see figure 5): “Oh! Is this a dream? Then I will make money writing and working as an instructor, and we will build a clean house and have fun starting a family and raising children…. As is the custom in the West, we will embrace and kiss each other on the lips…” (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 103, episode 12). Hyŏngsik has trouble living in the now, and often imagines how Westerners do things, dreaming of future scenarios.

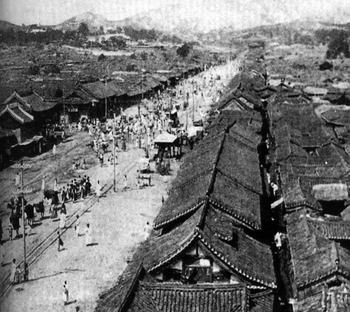

Figure 5. This photograph of an electric streetcar on Chongno Street (1902) captures the relationship between the past and the future in the transforming city. The advertisement on the streetcar reads, “O-ru-do Hi-yi-ro cigarettes.” Published with the permission of Garnet Publishing and Terri Bennett.

Even the interiority projected on the city is one of future forms (“clean” houses, married couples kissing on the lips, automobiles) taking over the “now,” a representational affect described by Mitchell as a double claim: “Something set up as representation [novel] denies its own reality … [but] in asserting its own lack, a representation claims that the world it replicates [Seoul, minjok] … must be… real” (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2000, 18; see also Hughes Reference Hughes2012, 406).

Groups of students in twos and threes ran about between the people on the street, chattering amongst themselves, as though on some urgent business. There were some women who still covered their heads when they left the house, and went about with a girl carrying a lantern to light their way, in the traditional style. The noise of a Western orchestra could be heard from the Umigwan, where what was known as an “action movie” (taehwalgŭk) was probably showing. Through the windows of the second floor of the Youth Association building flickered the shadows of youths walking about energetically, perhaps playing billiards. (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 140, episode 29; emphasis added)

In the novel's world picture of a modern Seoul above, “there were some women who still covered their heads … in the traditional style,” but their presence is fleeting against the universalizing sights and sounds of a “Western orchestra,” “action movie,” and YMCA building. Hence, the scenes make a double claim: first, as literary representation, and second, of a Seoul not yet “real” in the novel's 1910.

Hyŏngsik looked around the inside of the trolley, then sank his head down and closed his eyes. The trolley seemed to be going too slow deliberately [sic].… Flames rose in Hyŏngsik's breast. He thought of how Westerners in motion could ride a car at a time like this. Hyŏngsik imagined himself getting in a car at Chongno, and going across Ch’ŏlmul Bridge, then passing Paeogae and Tongdaemun, then going through the willow trees in front of the Mulberry Garden where the Royal Household cultivated silkworms, then passing Ch’ŏngnyangni, and racing towards Hongnung. (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 149, episode 37; emphasis added)

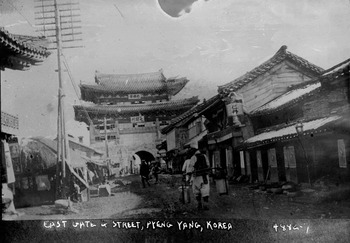

Here Hyŏngsik's mind projects onto the city a much more modern “West” where people in private automobiles whizz past electric streetcars that are “too slow.” The problem is that even the “now” that The Heartless claims to represent is not commensurate with the underdeveloped Korea that actually existed in the 1910s, testified to by the fact that Hyŏngsik's interiorized depictions of the city streets exaggerate the modernity of the Chongno Street captured in this 1920 image, with a view of the East Gate (Tongdaemun; see figure 6). Here, in between pedestrians, there are still palanquins alongside electric streetcars, but not one single automobile. The old belfry and city market area, Posingak, is visible in the center.

Figure 6. Chongno Street in 1920 (Sŏul Tŭkpyŏlsi Pangmulgwan 1998). Published with permission from the Seoul Historical Museum Archives.

As a modern stroller and an immobile passenger in electric streetcars, Hyŏngsik crosses the length of Seoul from South Gate Station (Namdaemun Station) to the southwest, to old Tea Village (Tabang-gol 茶洞) bordering Honmachi, and beyond the East Gate to the outskirts of Ch’ŏngyangni—the new pleasure grounds for the colony's rebellious youth (pullyang ch’ŏngnyŏn; see figure 7). Despite Seoul's centrality in this colonial modern experience, the story unfolds not only in the city's North Village, around and north of Chongno Street—the old east-west axisFootnote 21—but also in northern Korea's P'yŏngyang, around old Seven Star Gate and the famous Taedong River. In fact, this early text suggests that for Yi Kwangsu, Korea's representative modernizer, warmth and authenticity are not associated with the urban landscape but with a discarded northerly place. In thus delineating national and imperial centers (Seoul, Tokyo), the text simultaneously configures peripheries (colonial Korea) and localities (P'yŏngyang) that dwell all together in the author's alterity and maps a new topographical order.

Figure 7. On the same 1917 map shown in figure 3 are emplotted places of the everyday from The Heartless. Published with permission from the Yoon Daehyung Collection at Bumwoosa Publishing. (Labels added by the author.)

In P'yŏngyang, the Seven Star Gate was the local marketplace for the commoners of the premodern city, and the Taedong River is a famous site (myŏngji 名地) in Korean literary history. Just as Ongnyŏn's mother evoked powerful emotions pacing in search of her family on the familiar hills of P'yŏngyang's Peony Hill in the earlier Blood of Tears—Hyŏl ŭi Nu, a “new fiction” precursor to The Heartless by Yi Injik (Reference Injik1906–7)—so too does Hyŏngsik's walking in Chŏngju and P'yŏngyang unearth warm memories of belonging and childhood not identified with Seoul or Tokyo in the text.Footnote 22 In Yi's writing the metanarrative of the nation, invisible processes and memories of locals who still walked the area around Seven Star Gate were thus silenced by the rationalizing trajectory of national time, but yet remain legible in this literary representation.

The Heartless can be regarded as the first Korean work projecting the minjok onto the landscape through the movements and imagination of the male character Hyŏngsik (M. Shin Reference Shin, Shin and Robinson1999). Notably, however, Yŏngch'ae, the discarded female figure from the north, is the most dynamic character, imbued with an integrity and inner resolve lacking in both Hyŏngsik and Sŏnhyŏng. In fact, it is important to remember that Yi had initially begun The Heartless as The Story of Yŏngch'ae (Yŏngch'ae Chŏn), and not focusing on the male protagonist (Seo Reference Yongchae2011, 9; Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1936). So why does the author employ the most evocative traditional northern literary topoi (the famous “P'yŏngyang kisaeng” Kyewŏrhyang, Ch’ŏngnyu Cliff, the Taedong River, Peony Hill) to reference Yŏngch'ae? This article argues that although Yi Kwangsu and his protagonist are moving forward in “national time”—“The Heartless is the space of the origins of modern Korean culture, and also the space of the discovery of the male colonial elite's interiority” (Kwak and No Reference Youngmi and No2007, 548)—their hearts and minds (maŭm) are still in the north, not in Seoul, nor in Tokyo. I do not aim to plot male interior development through their objectification of female characters, but rather to argue in the Lefebvrian and Foucauldian sense for the simultaneity of disparate and layered spatio-temporalities as represented by Hyŏngsik, Yŏngch'ae, and Sŏnhyŏng (and their younger selves), even in a work like The Heartless, which has traditionally been heralded as a paean to modernity. This is why Yŏngch'ae the female character is as much a protagonist of the novel as is Hyŏngsik, and also why Hyŏngsik is depicted constantly running into fellow northerners in Seoul speaking the “P'yŏngyang dialect” (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 157, episode 36).Footnote 23 Thus through Hyŏngsik and Yŏngch'ae's relationship with the modernizing city we realize that the space of real people is never simply horizontal (Bhabha [Reference Bhabha1994] 2006), and in the figure of Yŏngch'ae, who is abandoned yet celebrated through P'yŏngyang's famous places, even the homecoming process is shown to be complicated.

Other-ness and Other Spaces

Many have remarked on the awkward tone of The Heartless, in both content and language (M. Shin Reference Shin, Shin and Robinson1999). I believe the “uncomfortable” tenor of the book does not stem from some formal or linguistic lack, but from the novel's function as a spatial projection of a transitional city. Stated differently, what is “lacking” and uncomfortable is the object of desire—the Korean “minjok”—itself. The awkwardness stems from a protagonist who has a rigorous relationship with a minjok, not really there in the “now” of the novel's 1910. This forward-moving colonial Seoul is both doubled by simulating Tokyo and haunted by suppressed memories of the north, a gendered space in the chauvinistic trajectory of imperial-national time (U Reference Miyoung2011).

This particular constellation of colonial alterity creates in Hyŏngsik an indecisive, neurotic central figure; a youth simultaneously dwelling in an Other place while going about his everyday affairs. Hyŏngsik regards himself a lonely pioneer almost singularly responsible for the future of Korean youth, while others in his age group enjoy the city.Footnote 24 Hyŏngsik is a figure in motion. He just came from Tokyo; works in Seoul; and, once he marries Sŏnhyŏng, will go study abroad in the United States, a metaspace representing the future. Although brilliant, Hyŏngsik is fundamentally detached and uncomfortable in the moment because his alterity is prefigured by the specter of multiple places, as well as of former and future selves.

International student travelogues from the period, such as Hyŏn Sangyun's “Life of Korean Students in Tokyo” (Tonggyŏng Yuhaksaeng Saenghwal, Reference Sangyun1914) and Yi Kwangsu's “Miscellaneous Letters from Tokyo” (Tonggyŏng Chapsin, 1916), describe lonely, challenging days trying to catch up in Japanese universities (see figure 8). As Benedict Anderson (Reference Anderson1998) notes in more general terms, the traveling colonial intellectual was constantly haunted by the “spectre of comparisons”; walking through Tokyo's Ginza, Yi Kwangsu's mind is projected back to and “doubles” Chongno (see figure 9), the old Seoul market, where listless “white-clad Korean people” loiter without an understanding that the rest of the world is speeding past them.Footnote 25 Yi is only able to engage in street voyeurism, overcome by colonial desire, and describes the Tokyo study period as lonely, without a place at home or work. Yi Kwangsu describes in vivid detail walking down the Tokyo streets, envying the confident postures of the rebellious bankara Footnote 26 First High School and Tokyo Imperial University students (“the Himalaya of universities”) with their wooden clogs (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 476).

Figure 8. Waseda University students in the 1910s. From section dated 1913–25 (the Taishō era; Waseda Hyakunen Hensan Iinkai Reference Hensan Iinkai1979). Published with permission from the Waseda University Library Archives.

Figure 9. Listless, white-clad Koreans in Chonggak, the central marketplace of the old city between 1900 and 1910, which is doubled while walking through Ginza (Ginbura) (Sŏul Tŭkpyŏlsi Pangmulgwan 1998). Published with permission from the Seoul Historical Museum Archives.

Ironically, the protagonist, Hyŏngsik, is just as isolated back in Seoul as he had been in Tokyo; there is work but still no home, no kohyang (furusato) or family. Yi Kwangsu had envied Tokyo's strutting bankara students, but in colonial Korea, Hyŏngsik is depicted as set apart from other young men like Sin Usŏn and Kim Hyŏnsu, who frequent Tea Village and Ch’ŏngnyangni, respectively the old and new pleasure quarters of the Seoul city in flux.

When he eventually reached his quarters in Kyodong, three young men, each in a rickshaw, raced past him towards Ch’ŏlmul-gyo [Bridge], bells ringing. Each man was dressed in a flashy new Western suit, and leaned back in his rickshaw half-drunk, with a kisaeng in another rickshaw in front of him. Hyŏngsik jumped out of the way and stood watching the six rickshaws race away in clouds of dust. (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 130, episode 24)

The rebellious bankara attitude Yi Kwangsu had so envied in Tokyo is a first-world posture, not suited for a backward Korea, with its yet incomplete modernity. In both Tokyo and Seoul, Hyŏngsik exhibits no sense of play (Maeda Reference Maeda and Fujii2004, 10); he is an outsider, looking but not engaging.

Hyŏngsik is equally displaced in the domestic spaces of Seoul. He enters his employer and future father-in-law Elder Kim's house for the first time. The Elder Kim character parallels Natsume Sōseki's father figure, Nagai Toku, from Sorekara, who is likewise a wealthy modernizer in the transitioning space, but one who exhibits only the surface trappings of modernity (Sōseki [Reference Sōseki and Field1909] 1988, 30).

His home was quite large, with more than ten rooms sprawled about on either side of the front door, for servants’ quarters. Intimidated by such status and wealth, Hyŏngsik felt frightened on the one hand, and had unpleasant qualms on the other. He cleared his throat and called out for a servant to answer the door. “Is anyone home?” No matter how hard he tried, though, his voice did not sound authoritative, but young and quavering, exactly like the voice of a person who has just come to Seoul from the countryside for the first time and is calling out for a servant to answer the door. (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 80, episode 2; emphasis added)

Above, Hyŏngsik has just returned from the more modern Tokyo, but when visiting Elder Kim's house, he feels like some country bumpkin who has just “come up” to Seoul. Elder Kim's daughter, Sŏnhyŏng, eventually becomes Hyŏngsik's fiancé, and they are to be sent abroad together. Hyŏngsik will marry the girl “of his dreams” and go to the land of his dreams (the United States), but he cannot seem to leave behind his past, a coeval past that interrupts Hyŏngsik's everyday life the moment he reunites with Yŏngch'ae: “As the two of them looked at each other, events from over ten years ago flashed through their minds like a motion picture. The events appeared vividly before their eyes as though it were yesterday. The happy times they had spent together” (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 91, episode 6).

P'yŏngyang and Yŏngch'ae: Chŏng 情 and Memories of a Hometown (Kohyang, Furusato)

The reunion in Seoul of the two northerners, Hyŏngsik and Yŏngch'ae, is a portal through which their past ephemerally reveals itself and ruptures Seoul time (Chakrabarty Reference Chakrabarty2000): “The memories flashed through Hyŏngsik's mind like lightning, and he wiped his tears away and looked at Yŏngch'ae, who had put her head down on the desk and was weeping” (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 90, episode 6).Footnote 27 After Hyŏngsik finds Yŏngch'ae's suicide note, he rushes to South Gate Station and boards the train (Seoul-Ŭiju) to P'yŏngyang. Nearing the traditional northern capital, he looks upon the landscape, now imbued with images of Yŏngch'ae and, simultaneously, heroic “famous kisaeng” (myŏnggi 名妓) throwing themselves into the famous Taedong River in P'yŏngyang.

Hyŏngsik opened the window and looked in the direction of Nŭngna Island. Nothing could be seen distinctly in the early morning haze, but Hyŏngsik had seen P'yŏngyang several times and could place the general terrain. “That must be Nŭngna Island,” he thought. “That would be Moran [Hill], and that must be Ch’ŏngnyu Cliff.” He thought of the letter from Yŏngch'ae that he had read the day before. “I am going to throw myself into the blue waters of the Taedong Tiver,” she had written. He sighed. He could see in the darkness near Nŭngna Island. “I want to let the waves wash my unclean body. I want the heartless creatures of the water to tear this body to pieces.” Hyŏngsik could almost see Yŏngch'ae body floating beneath the steel bridge. He stuck his head out the window and looked down at the waters. He could see the waves flowing in round currents against the pillars of the bridge…. (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 197, episode 55; emphasis added)

During the Hideyoshi Invasions (Imjin Wars, 1592–98), Kyewŏrhyang—the legendary sixteenth-century kisaeng whose name Y’ŏngch'ae had assumed professionally—had lured her lover, the Japanese general Konishi Yukinaga (1555–1600), into a trap and sacrificed herself for Chosŏn, while, some accounts say, pregnant with his child (Chŏng Reference Chiyŏng2007).Footnote 28 Nongae, another “famous kisaeng,” had hurled herself into the river while holding another Japanese general in her deadly embrace. Travel to and walking around the P'yŏngyang area thus opens up space to “the body of legends that is currently lacking” in the colonized space being covered over by the veil of capitalist modernity (Certeau Reference Certeau1984, 106–7).

Wandering around the familiar P'yŏngyang streets looking for Yŏngch'ae conjures up for Hyŏngsik memories of the first time he had “come up” to the regional capital from a small village in Chŏngju. Hyŏngsik's mind is now displaced when he comes upon an old man at Seven Star Gate whom he recognizes from his past, sitting on a wooden platform in the exact same spot as before. The area has become rundown and deteriorated, but the old man has not changed at all, “swaying his body back and forth,” watching time go by: “[The old man] knew nothing about railroads, telegraphs, telephones, submarines or torpedoes. He lived outside Seven Star Gate, less than five li away from Great Unity Gate Street, and yet he knew nothing about what took place every day and every night within the city of P'yŏngyang” (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 215, episode 63). Hyŏngsik thinks the old man is made of stone, calling him a “petrified man,” and when asked if he knew the old man, Hyŏngsik says, “Before, but not anymore.” Hyŏngsik walks right by, and yet, traversing the shantytown area around Seven Star Gate, he remembers vividly in his mind the first time he had been there as an eleven-year-old.

Sitting in his rickshaw, Hyŏngsik remembered the first time he had come to P'yŏngyang. He had arrived one morning in the early spring through [the Seven Star Gate] Ch'ilsŏngmun, his feet wrapped in cotton cloth, his hair still in a long braid, with a white ribbon because he was in mourning for his parents. It certainly is a big city, he had thought, looking down at the city streets from just inside Ch'ilsŏngmun. … Hyŏngsik had seen, for the first time, a Japanese store on a street near Taedongmun (the Great Unity Gate). (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 200, episode 56; emphasis and parentheses added)

Hyŏngsik had gone through the old Seven Star Gate (see figure 10), through which the “invisible” local population had been entering for generations, and not the Great Unity Gate (Taedongmun; see figure 11), the site of the Japanese-built railway station, and therefore the focus of new urban planning in modern P'yŏngyang (see figure 12). Hyŏngsik recounts his first time seeing the Japanese then. Returning home now from the “national” capital of Seoul (and in a sense, also from Tokyo), however, Hyŏngsik enters P'yŏngyang on the modern train, this time through the flourishing city center of the Great Unity Gate area and not the old Seven Star Gate.

Figure 10. “Forgotten” Ch'ilsŏngmun (Seven Star Gate). Published with permission from the University of Southern California, the Reverend Corwin & Nellie Taylor Collection.

Figure 11. Taedongmun (Great Unity Gate), the modernized area in P'yŏngyang (1915–20), where the Japanese-built railway station was. Published with the permission of the Library of Congress.

Figure 12. In The Heartless, Hyŏngsik enters this time through the modernized Great Unity Gate (Taedongmun) area railway station, shown here in this 1910s P'yŏngyang map. The old Seven Star Gate area is no longer even noted in this modern map. Published with permission from Professor Changmo Ahn. (Labels added by the author.)

Hyŏngsik's journey “backward in time” from Tokyo to Seoul to P'yŏngyang, during which the lost memories of home ephemerally emerge as Other stories, punctures through stratified temporal axes (Tokyo → Seoul → P'yŏngyang → Chŏngju), arriving finally at his birthplace, Chŏngju, with its memories and family.

When he heard her say “older brother,” though, he felt somewhat embarrassed. Hyŏngsik had one younger sister, and three female cousins.… Whenever he went to his hometown on vacations, Hyŏngsik would go to see his three cousins first. His cousins were very fond of him, and were glad to see him.… Indeed, Hyŏngsik went to his hometown on school vacations just to hear those two cousins calling him “older brother [oppa].” (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 214, episode 62; emphasis added)

He thought of the small village outside of Chŏngju where he was born, with its single water bearer and noodle shop: “There sure are a lot of water bearers here [P'yŏngyang], he thought. The only water bearer in the village where Hyŏngsik grew up was at a small tavern where wine was brewed, and where noodles were made in winter” (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 200, episode 55; emphasis added). Northerly memories are inscribed with uncharacteristic warmth and bittersweet nostalgia for his scattered family and cousins who call him, affectionately, “older brother” (oppa). Chŏngju, outside of P'yŏngyang, is the under-noted home, which in the 1900s Yi Kwangsu had left to become a modern subject, and is today a forgotten locality, further obscured in a divided Korea and also in Yi Kwangsu studies.

Benjamin's Angel

Michael Shin (Reference Shin, Shin and Robinson1999) has argued that the much-studied final flood scene—where Hyŏngsik, Sŏnhyŏng, and Yŏngch'ae (rescued from herself fantastically by female student Pyŏnguk on another train ride, and herself developed into a “new woman”) disembark from the train en route to study abroad in Japan and the United States—is the climactic moment of the discovery of the minjok. The characters “see” the inner person (sok saram) in the flood victims and perform an impromptu fundraising concert in the spirit of compassion and a newly discovered “national” solidarity. This, structurally, is the pedagogical apex (Bhabha [Reference Bhabha1994] 2006, 139–70) of the novel wherein minjok as a regime of translation is cast on the population, but it also reads to us as a somewhat affected moment, testifying to the “uncomfortable” and projected state of national identity itself on the as yet untransformed landscape.

A lived performative moment (Bhabha [Reference Bhabha1994] 2006) also occurs on a railway car, but in a previous train ride scene where Hyŏngsik is depicted having left Yŏngch'ae for dead in P'yŏngyang, heading back towards Seoul, the city of his future. Returning to the colonial capital where the task of nation-building awaits, Hyŏngsik is characteristically torn, caught between past and future, hometown and the city, Korea and empire.

Yŏngch'ae's face appeared the most often, and for the longest time.… “Have I been wrong?… Have I not been too heartless ( 無情)? Shouldn't I have spent more time looking for Yŏngch'ae? If she were dead, shouldn't I have at least looked for her body? Shouldn't I have stood by the Taedong River and wept hot tears into the waters? Yŏngch'ae took her life, thinking of me. I shed no tears for Yŏngch'ae, though. Ah, how cruel I am. I am not a human being.” The train raced towards the South Gate (Namdaemun). Hyŏngsik wanted to turn the train around and go back to P'yŏngyang. Hyŏngsik finally arrived at Namdaemun and got off the train, but, his mind was drawn towards P'yŏngyang. (Yi Kwangsu Reference Kwangsu1917a, 222, episode 66; emphasis added)

Yŏngch'ae represents tradition and slavish devotion to Confucian pasts, which all modernizers had to relinquish to move forward. Likewise P'yŏngyang was, for the forward-moving Seoul, the “sister city” Hyŏngsik abandoned to run towards civilization and achieve modern nationhood, like Benjamin's (Reference Benjamin and Zohn1969, 257) angel of history (“Angelus Novus”). Hyŏngsik hurls himself into the future on the railway, but is facing backward with uncertainty. Yi Kwangsu says this moment marks the discovery of Hyŏngsik's inner person (sok saram)—and yet, this is strangely the point at which Hyŏngsik calls himself “not a human being,” in the same way Yi Kwangsu had entreated his “little brother” (tongsaeng) at the train station in Japan in the earlier “From Tokyo to Seoul” travelogue not to think him “heartless” because he had to return to Korea to achieve “their goals” and reconstruct (kaejo) their homeland.

Yi Kwangsu's letters, travelogues, and fiction of the 1910s suggest that the very condition of global cosmopolitanism at its most upwardly mobile was built upon similar ambivalent movements away from local hometowns to “heartless” centers of capitalist development. Warm attachments and personal recollections nonetheless persist, cocooned in layers of memories, which, despite the violent erasure that is modernity and the minjok itself, exist coevally as local images and remembrances of brave heroines like Yŏngch'ae's namesake Kyewŏrhyang, who sacrificed themselves for love and country. To be modern required heartlessness, and, like Benjamin's angel, Hyŏngsik heartlessly rushes towards the future. What we had forgotten, however, is that even in the midst of this breakneck trajectory, the angel is not facing forward, but is looking back at the things it has destroyed in its horrible path.

Conclusion

Minjok is a violent epistemic regime that, in the translation process, veils lived practices of alterity and subsumes other identities, places, and memories under the sign of nation. This reading engages a postcolonial problematic borne of the inevitable outcome of capitalism's spatial encroachment. Modernity was a universalizing force that Yi as a colonial intellectual had to stem by creating a particular, national interior, reflected in a novelistic urban space that showcased a city transforming from ancient Hanyang (premodern Seoul) to the modern capital, Keijō (colonial Seoul). Still, unacknowledged spatial practices in and around historical Seoul and its sister city of P'yongyang persistently disrupted the modern time of The Heartless’s capital. The competing identities of nation-versus-empire that played out over the visible landscapes of the transforming city veiled—as Hyŏngsik, Yŏngch'ae, and the other northerners’ movements show—the layered stories behind the processes of “going up” (sanggyŏng 上京) to urban centers from forgotten hometowns.

Yi was a key Korean nationalist; at the same time he was a bilingual, Waseda University–educated Japanese imperial subject. Starting in the 1920s, Yi Kwangsu became a dominant member of the colonial intellectual sphere; hardly an invisible Seoulite. Colonial bourgeoisie enjoyed the consumerism and cultural capital their class afforded them, and yet despite their cooption by the state, they remained politically marginalized and disenfranchised in the realm of realpolitik, even in their own capital city of Seoul. A discursive nod to Yi Kwangsu's invisibility in the larger empire (colonial difference) is always challenged in Korean studies by the insistence of his centrality in the colony as bourgeois elite (class). This uncomfortable juxtaposition created by the axes of class and colonial difference remains unresolved, as long as Korean politics itself continues to be polarized by the two often conflicting imperatives of overcoming peninsular division (left versus right) versus becoming more globally visible as a nation. This is also why Yi Kwangsu remains one of the most controversial figures in left-leaning Korean politics, but remains at the same time one of a small handful of writers from the peninsula whom other East Asianists can readily identify in a global academe where Korean studies is only just starting to become visible.

Casting the analytical framework outside national discursive space to consider the larger Japanese empire and beyond can render colonial Korea doubly colonized and veiled, however, insofar as Japan frames itself as culturally colonized, thereby masking its colonizer status. What are doubly relinquished and forgotten, underneath the more vociferous narratives of Japanese empire and Korean minjok, are the local stories. Reading beyond the metanarratives of class, nation, and empire, we are able to glimpse the practices of everyday folk and “country bumpkin” past selves in the memories opened up in this novel through the homecoming act of a younger Hyŏngsik who had moved up to the regional center of P'yŏngyang years ago. Memories of a hometown, now even more inaccessible through decades of national division, add another layer to Yi's much-studied in-betweenness. This trajectory was narrated as temporal, since refigurations of hometown and originary space were felt as movements backward through time. Such local peregrinations were largely illegible to the state, but are inscribed in colonial literature, testifying to a glocal (global yet local) identity in which colonized urbanites were cosmopolitan and yet regularly code-switched to their hometown dialects (Appadurai Reference Appadurai1996).

As Hyŏngsik is depicted in The Heartless’s colonial Seoul running into people speaking the P'yŏngan dialect, so too did contemporaries recall Yi Kwangsu often slipping into the northern accent with hometown friends like Chu Yohan and his mentor, An Ch'angho.Footnote 29 Yi Kwangsu read Western philosophy at a top Tokyo university, but when he lost his first son Ponggŭn to blood poisoning in 1934, the writer resigned from his prestigious position as editor of the Chosŏn Daily News, shaved his head (sakbal 削髮), and retreated into the Korean Diamond Mountains (Kŭmgangsan 金剛山), intending to live out his days as a monk. Just five years later, Yi would serve as president of the Chosŏn Writer's Association (Chosŏn Munin Hyŏphoe), which was founded to bring the colonial literary world into closer collaboration with the empire. Yi Kwangsu thus embodied the local past, the colonial present, and the national future of the minjok together throughout his life.

In juxtaposing these uncomfortable cultural and temporal regimes, one is reminded of the description of India as a country that “lived hundreds of years at once” from Chakrabarty's Provincializing Europe (Reference Chakrabarty2000), a call to arms for postcolonial voices to articulate agency from positionalities beyond the now old imperial centers. This study similarly emphasizes these stories, not only in the 1930s, an era more conventionally identified with the later “overcoming modernity” (“return to Japan”) movement within the larger empire, but from as early as the 1910s in a time usually periodized by modernity's forward-moving drive. Insistence on spatiality to neutralize the totalizing aggressions of capitalist, national, and imperial time sets even the much-politicized labels of traitor and bourgeoisie against a more expansive landscape of glocality wherein the universal and the local, the Japanese and Korean, city and country together create the alterity fundamental to the modern condition—a more forgiving postcolonial move that, of course, is not without its detractors (Em Reference Em2013).

Modern capitalism was a spatial encroachment transforming all it touched across the globe, subsequently clearing the way for unprecedented movement across shifting borders. Thus mobility became a proud badge of the modern. Yi Kwangsu, both patriot and collaborator, was in the 1910s one of the first Korean travelers to transcend the political nation by desiring global cosmopolitanism along with its immanent departures to the glittering modern cities, and its inevitable returns to the country, to hometown, to the past. It is specifically because The Heartless is Korea's first modern novel that the text bears witness to the fundamental condition of alterity in (post)colonial subjectivity, where neither the modern nor the colonial is privileged over the local. This is a way of analyzing fiction that is capable of reading against the author's intention and professed ideology (“civilization and enlightenment”) by what the text itself uncovers. The point is that even though colonial writers described broken, dislocated, and lonely alterities making their ways through the uncertainties and anxieties reflecting their loss of cultural authority, by reading beyond the authors’ intentions and beliefs, we are able to arrive at a story that is not just about loss nor political betrayal, but about departures and returns, and about survival and futurity.Footnote 30

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of the Journal of Asian Studies for their helpful comments, as well as Brett de Bary, Todd Henry, Seo Yongchae, Kim Baek Yung, Ahn Changmo, Leslie Adelsen, the 2014–15 Cornell Mellon Society Diversity Fellows, and Andrew Harding for their insights and editing suggestions. This article is published to commemorate the centenary of The Heartless’s publication.

Appendix: Glossary of People and Places

People:

Elder Kim—Wealthiest man in Seoul, father to Sŏnhyŏng.

Kim Sŏnhyŏng—Hyŏngsik's new love, from a wealthy Seoul family, will study in the United States.

Kyewŏrhyang—Famous sixteenth-century kisaeng, c. the Hideyoshi Invasions (Imjin Wars, 1592–98), who sacrificed her life for her country by luring General Konishi Yukinaga into a trap.

Pak Yŏngch'ae—Old love of Hyŏngsik from the north. Now a female entertainer (kisaeng), “Kyewŏrhyang.”

Pyŏnguk—Young female international student who meets Yŏngch'ae when she is on a train heading to P'yŏngyang to throw herself into the Taegong River. Pyŏnguk takes Yŏngch'ae to her home and mentors her.

Scholar Pak—Hyŏngsik's old mentor from the north, Yŏngch'ae's late father.

Sim Usŏn—Hyŏngsik's friend from school in Tokyo.

Yi Hyŏngsik—Male protagonist, English teacher recently arrived from study abroad in Tokyo.

Places in Seoul:

An (guk)-dong—A neighborhood in North Village where many landed elite lived.

Central Palace—Kyŏngbok Palace.

Chongno Street—Central east-west axis demarcating North Village and South Village (Honmachi), also where the old central market was located.

Ch’ŏngnyangni—New suburb to the east of old Seoul, where a modern train station was built. It became a new pleasure ground for Modern Boys and Girls.

East Gate—Tongdaemun.

Hangyang/Hansŏng—Names of Seoul during the previous Chosŏn dynasty (1392–1910).

Honmachi—South Village, or Japantown.

Keijō—Name of colonial Seoul.

North Village—Pukch'on, or Koreatown.

Pagoda Park—The first modern park in Seoul, built in the late nineteenth century by foreign adviser McLeavy Brown during the reign of King Kojong, to commemorate the site of the fifteenth-century Wŏngak Temple, and an ancient ten-story pagoda, thought to have been a gift from the in-law Mongol emperor to the Koryŏ state.

South Gate—Namdaemun.

South Gate Station (Namdaemun Station)—Main railway station, linking Seoul to the rest of Korea.

Tea Village (Tabang-gol)—Neighborhood near Chongno Street where kisaeng (female entertainers) worked. Described with lanterns glowing in the streets.

Places in the North:

Chŏngju—Town outside P'yŏngyang where Yi Kwangsu (also the characters Yi Hyŏngsik and Pak Yŏngch'ae) was from.

Ch’ŏngnyu Cliff—Famous stone cliffs at Taedong River, north of the old city.

Great Unity Gate (Taedongmun)—Eastern gate of P'yŏngyang, where the Japanese built a modern railway station, making it the bustling new city center.

Nŭngna Island—Island to the east of P'yŏngyang, on the Taedong River.

Peony Hill (Moranbong)—A very famous place in Korean cultural history.

P'yŏngyang—North(west)ern capital.

Seven Star Gate (Ch'ilsŏngmun)—Northwestern entryway into the historical P'yŏngyang city, often described in popular literature as a local spot with poor residents and shantytowns, but not depicted in later modern maps.

Taedong River—Main river in the city of P'yŏngyang. “Throwing oneself into the Taedong River” is a famous Korean cultural trope.