First-generation antipsychotic long-acting injections (FGA–LAIs) were introduced in the 1960s, Reference Johnson1 and continue to be widely used today in both the USA Reference Shi, Ascher-Svanum, Zhu, Faries, Montgomery and Marder2 and the UK Reference Paton, Lelliott, Harrington, Okocha, Sensky and Duffett3,Reference Barnes, Shingleton-Smith and Paton4 for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. In meta-analyses antipsychotics are superior to placebo in reducing relapse in schizophrenia, Reference Leucht, Barnes, Kissling, Engel, Correll and Kane5 and randomised studies have shown that continuous maintenance medication is associated with lower relapse rates than intermittent targeted medication given only when there are early warning signs of a possible relapse. Reference Carpenter, Hanlon, Heinrichs, Summerfelt, Kirkpatrick and Levine6,Reference Herz, Glazer, Mostert, Sheard, Szymanski and Hafez7 In practice the effectiveness of maintenance antipsychotic treatment is often undermined by poor adherence, with Cramer & Rosenheck estimating a medication adherence rate in schizophrenia of 58%. Reference Cramer and Rosenheck8 Stopping antipsychotic medication is a common cause of relapse, Reference Robinson, Woerner, Alvir, Bilder, Goldman and Geisler9 and even a 10-day period of missed medication has been associated with an increased risk of readmission due to relapse. Reference Law, Soumerai, Ross-Degnan and Adams10 Partial adherence may lead to poor symptom control irrespective of an increased risk of relapse, so by improving medication adherence LAIs may reduce relapse and improve symptom control. The regular contact with nursing staff that accompanies LAI treatment may have further benefits. An important proviso is that this argument assumes that those who adhere poorly to a regimen of tablets will accept an injection. Some patients will not, and so LAIs are not a panacea for adherence problems nor are they the only strategy by which to improve adherence.

In summary, there are intuitive reasons why LAIs may improve clinical outcomes but the key issue is whether evidence supports this. In this article we systematically review studies that compare the effectiveness of FGA–LAIs with both first- and second-generation antipsychotic oral medication in schizophrenia. First-generation antipsychotic LAIs are used in other disorders, including bipolar disorder, Reference Bond, Pratoomsri and Yatham11 but this is less frequent and outside the remit of this review. We have reviewed both randomised controlled studies and observational studies as they assess different outcomes. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assess efficacy, i.e. does a drug lead to benefit in ideal circumstances. Observational studies assess effectiveness, i.e. does a drug have benefit in the real world where dose, patient characteristics and follow-up may be more variable than in an RCT.

Method

Search strategy

A systematic search of the MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO databases was conducted in September 2008 using the terms antipsychotic, depot and long-acting injection, and mapping to MeSH terms, with the limits humans, adults, clinical trial, meta-analysis, randomised controlled trial, comparative study, English. There were no limitations by date. Abstracts of articles were reviewed against our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The references cited by included studies were reviewed for additional relevant cited articles, and the citation search facility was employed to identify further potentially relevant original studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For inclusion, studies were required to:

-

(a) include a group of patients treated with an FGA–LAI;

-

(b) include an oral antipsychotic comparator (first- or second-generation);

-

(c) provide original quantitative data on efficacy or effectiveness;

-

(d) (for RCTs and prospective observational studies) be restricted to those that recruited patients with schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder or schizophreniform disorders.

The last inclusion criterion was not applied to retrospective studies as these frequently reported on the outcome of a cohort of patients treated with LAIs irrespective of diagnosis. No specific quality threshold was set for inclusion of studies. Studies were excluded if there were fewer than 20 patients in the LAI arm, if no original patient data were reported (e.g. ‘modelling’ studies) or if the comparator group was given a placebo, another FGA–LAI or risperidone LAI.

Statistical analysis

Included studies were divided into four groups: RCTs, prospective observational studies, mirror-image studies and other retrospective observational studies. Quantitative data were extracted. In some mirror-image studies admission and in-patient data were presented only in graph form in the original articles and/or P-values were not given. Where possible we have extrapolated the missing data and calculated P-values using data from the original publications. The summary table for mirror-image studies (see Table 2) indicates where secondary calculations have been made. No further statistical analysis was applied.

Table 1 Prospective observational studies with a first-generation antipsychotic long-acting injection cohort

| Country | Selection of participants a | Follow-up period | LAI group | Oral comparator groups | Main outcome b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conley et al (2003) Reference Conley, Kelly, Love and McMahon23 | USA | Patients discharged from in-patient care on LAI or oral medication | 1 year | Fluphenazine decanoate (n = 59) and haloperidol decanoate (n = 59) | Clozapine (n = 41), risperidone (n = 149), olanzapine (n = 103) | One-year risk of readmission for each oral antipsychotic was lower than for haloperidol decanoate but not significantly different from fluphenazine decanoate |

| SOHO study (Haro et al 2006, 2007) Reference Haro, Novick, Suarez, Alonso, Lépine and Ratcliffe21,Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 | 10 European countries | Patients who switched 3 years antipsychotic on out-patient basis | 3 years | Various FGA–LAIs (n = 348 at baseline) | Conventional cohort and various atypical cohorts. Statistical analysis limited to comparing other cohorts, including the LAI cohort, with the olanzapine cohort (n = 4247 at baseline) | 1. Compared with olanzapine, LAIs associated with lower odds ratio of achieving remission, higher odds ratio of relapse, and higher rate of all-cause discontinuation of medication. |

| 2. Outcome measures given above similar for oral conventional and LAI cohorts (P-values not provided) | ||||||

| Tiihonen et al (2006) Reference Tiihonen, Walhbeck, Lönnqvist, Klaukka, Ioannidis and Volavka19 | Finland | Consecutive patients discharged after first admission | Mean 3.6 years | Perphenazine LAI (187 person-years of follow-up) | Various antipsychotic cohorts. Statistical comparison with oral haloperidol (107 person-years of follow-up) | Compared with oral haloperidol, perphenazine LAI was associated with lower relative risks of both rehospitalisation and all-cause discontinuation of treatment |

| US–SCAP (Zhu et al, 2008) Reference Zhu, Ascher-Svanum, Shi, Faries, Montgomery and Marder20 | USA | Patients starting oral or LAI haloperidol or fluphenazine | 1 year | Haloperidol decanoate (n = 47) or fluphenazine decanoate (n = 50) | Haloperidol (n = 109) or fluphenazine (n = 93) | Compared with oral medication, those treated with LAI had longer mean time to all-cause discontinuation of medication and were twice as likely to stay on medication |

FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; LAI, long-acting injection; SCAP, Schizophrenia Care and Assessment Program; SGA, second-generation antipsychotic; SOHO, Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes

a. All participants had schizophrenia, schizoaffective or schizophreniform disorders

b. Differences in outcomes between LAI and oral treatment are statistically significant unless otherwise stated

Table 2 Summary of mirror-image studies of first-generation antipsychotic long-acting injections

| Country | Entry criteria: duration of LAI treatment | Mean duration of LAI treatment | LAI (no. of participants) | Analysis of index admission | Total in-patient stay (previous treatment v. LAI), days | Total no. of admissions (previous-treatment v. LAI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denham & Adamson (1971) Reference Denham and Adamson25 | UK | More than 1 year | 24.8 months | Fluphenazine decanoate or enanthate (n = 103) | Excluded | 8713 v. 1335 (P not given) | 191 v. 50 (P < 0.005 a ) |

| Gottfries & Green (1974) Reference Gottfries and Green26 | Sweden | No minimum treatment period | Not stated (most treated for 2–4 years) | Flupentixol decanoate (n = 58) | Not stated | 12562 v. 2981 a (P < 0.005 a ) | 103 v. 37 (P < 0.005) |

| Morritt (1974) Reference Morritt27 | UK | 1 year | 12 months | Fluphenazine decanoate (n = 33) | Not stated | 2379 v. 801 (P<0.005 a ) | 60 v. 17 (P < 0.005 a ) |

| Johnson (1975) Reference Johnson28 | UK | > 1 year | 15 months | Fluphenazine decanoate (n = 140) | Excluded | 56% reduction b (P not given) | 38% reduction b (P not given) |

| Lindholm (1975) Reference Lindholm29 | Sweden | > 1 year | 28.8 months a | Perphenazine enanthate (n = 24) | Excluded | 6607 v. 1151 a (P<0.005 a ) | 76 v. 34 (P < 0.05) |

| Marriott & Hiep (1976) Reference Marriott and Hiep30 | Australia | > 1 year | 22.7 months | Fluphenazine decanoate (n = 131) | Split by first dose | 12434 v. 5619 (P < 0.005 a ) | Not assessed |

| Polonowita & James (1976) Reference Polonowita and James31 | New Zealand | No minimum period of treatment required | 13.4 months | Fluphenazine decanoate (n = 35) | Split by first dose | 1463 v. 327 (P<0.005) | 60 v. 22 (P < 0.005) |

| Devito et al (1978) Reference Devito, Brink, Sloan and Jolliff32, c | US | Adherent for > 3 consecutive months | Not stated | Fluphenazine decanoate (n = 61) | Not stated | 3329 v. 314 a (P < 0.05) | 93 v. 33 (P < 0.05) |

| Freeman (1980) Reference Freeman33 | UK | > 1 year | Not stated (12.5 years follow-up) | Not stated (n = 143) | Excluded | 19510 v. 4376 (P not given) | Not assessed |

| Tan et al (1981) Reference Tan, Ong and Chee34 | Singapore | 2 years | 24 months | Fluphenazine decanoate (n = 127) | Not stated | 5264 v. 2533 (P not given) | 175 v. 140 (P not given) |

| Tegeler & Lehmann (1981) Reference Tegeler and Lehmann35 | Germany | > 1 year | 62.4 months | Various d (n = 76) | Excluded | 18620 v. 3192 (P < 0.005) | 198 v. 68 a (P < 0.005) |

| Total e | 25.4 months (n = 669) | Various | 90 881 v. 22 629 (n = 791) Per patient: 114.9 v. 28.6 | 956 v. 401 (n = 517) Per patient: 1.8 v. 0.8 |

LAI, long-acting injection

P-values were stratified into the following groups: P < 0.05 and P < 0.005

a. Denotes P-values or approximate figures we have extrapolated from the original published data

b. Absolute figures not available

c. In addition to the mirror-image analysis, the LAI group in Devito et al was compared with a separate oral cohort (see Table 3)

Table 3 Retrospective observational studies with a first-generation antipsychotic long-acting injection cohort (excluding mirror-image designs)

| Study | Country | Participants | Follow-up period | LAI group | Oral comparator groups | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devito et al (1978) Reference Devito, Brink, Sloan and Jolliff32, a | USA | Out-patients from general clinic or depot clinic. Most had schizophrenia. Groups were not matched | 1 year | Fluphenazine decanoate (n = 61) | Various (n = 61) | Fewer patients in the LAI group were admitted than in the oral group (25% v. 44%) during the 1-year follow-up |

| Marchiaro et al (2005) Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 | Italy | Patients who had completed 2 years' treatment on an oral drug or LAI. All had schizophrenia. Groups were matched as closely as possible on demographic and clinical variables | 2 years | Various FGA–LAIs (n = 30) with most common being haloperidol decanoate | Various second-generation drugs (n = 30) | No difference in terms of 1- and 2-year readmission rates or the number of episodes of self-harm. During the study anticholinergic drugs were prescribed more frequently in the LAI group than in the oral group (47% v. 13%, P = 0.01) |

FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; LAI, long-acting injection

a. In addition to comparing the LAI cohort with a separate oral cohort these authors conducted a mirror-image analysis of the LAI cohort by making comparison with preceding oral treatment (see Table 1 for results)

d. Includes penfluridol, fluphenazine decanoate, fluspirilene and flupentixol decanoate

e. Total values based on available data in each column, e.g. mean LAI treatment duration is based on 8 studies, total in-patient stay based on 10 studies, etc.

Results

Search strategy

The initial search strategy revealed 249 potentially relevant study abstracts, which were individually scrutinised against the inclusion criteria. Seven further possible studies were identified through citation search. After inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, the remaining studies were categorised as RCTs (1 meta-analysis that considered FGA–LAIs as a total group and 1 RCT); prospective observational studies (4 studies); mirror-image studies (11 studies); other retrospective observational studies (2 studies).

The one meta-analysis of FGA–LAIs v. oral medication that we identified was part of a comprehensive systematic meta-review of LAIs by Adams et al. Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12 This review was based on a synthesis of data from eight Cochrane reviews of individual FGA–LAIs in patients with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses. Since the Adams review was published, five of the Cochrane FGA–LAI reviews on which it was based have been updated. Reference Adams, David and Quraishi13–Reference Dinesh, David and Quraishi17 These updates either contain no data comparing LAIs with oral medication or show no significant difference in efficacy between oral and LAI. Consequently the updated Cochrane reviews give no reason to doubt a key result of the meta-analysis by Adams et al, namely that relapse rates do not differ between LAI and oral medication. Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12 In view of this the individual updated Cochrane reviews are not detailed further in this paper.

Randomised controlled trials

The meta-analysis by Adams et al of FGA–LAIs v. oral antipsychotics provided data on several outcomes, including relapse (Fig. 1). Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12 The relapse data are based on a total sample of 848 patients randomised to an FGA–LAI (fluphenazine decanoate, fluspirilene decanoate, pipotiazine palmitate) or an FGA–oral medication (including chlorpromazine, haloperidol, penfluridol and trifluoperazine) (Fig. 1). The duration of included trials varied (4 weeks to 2 years), but most patients took part in trials of at least a year in duration. The risk of relapse did not differ between the two groups (RR = 0.96, 95% CI 0.8–1.1). In an analysis of 127 patients treated with three FGA–LAIs (fluphenazine decanoate, fluphenazine enanthate and haloperidol decanoate), global improvement (assessed using the Clinical Global Impressions scale) was more likely with FGA–LAI than with FGA–oral medication, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 4 (95% CI 2–9). The FGA–LAI and FGA–oral groups were similar in terms of study attrition, the need for adjunctive anticholinergic medication and incidence of tardive dyskinesia (Fig. 1). Anticholinergic medication, a proxy marker for the presence of extrapyramidal symptoms, was prescribed to 69% of the FGA–LAI cohort and 65% of the FGA–oral cohort. The prevalence of tardive dyskinesia in the FGA–LAI cohort was 9.0% and in the FGA–oral cohort it was 14.1%.

Fig. 1 Outcomes for antipsychotic treatment: long-acting injection (LAI) v. oral. From Adams et al, Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12 reproduced with permission.

We identified one RCT not included in the original or updated Cochrane reviews of FGA–LAIs, namely that by Arango et al. Reference Arango, Bombin, Gonzalez-Salvador, Garcia-Cabeza and Bobes18 This small RCT compared oral zuclopenthixol (n = 20) with zuclopenthixol decanoate (n = 26) over 1 year in patients with schizophrenia and a history of violence. A lower frequency of violent acts was seen in the LAI group but end-point scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) did not differ.

Prospective observational studies

We identified four prospective observational studies that compared an FGA–LAI with one or more oral antipsychotic cohorts (Table 1). Reference Tiihonen, Walhbeck, Lönnqvist, Klaukka, Ioannidis and Volavka19–Reference Conley, Kelly, Love and McMahon23 These studies had various pragmatic outcome measures, including risk of readmission and time to all-cause discontinuation of medication. Results were mixed. Two studies found a better outcome for FGA–LAI compared with an FGA–oral. Reference Tiihonen, Walhbeck, Lönnqvist, Klaukka, Ioannidis and Volavka19,Reference Zhu, Ascher-Svanum, Shi, Faries, Montgomery and Marder20 The Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes (SOHO) study found poorer outcomes for FGA–LAI than oral olanzapine, Reference Haro, Novick, Suarez, Alonso, Lépine and Ratcliffe21,Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 and a fourth study found oral antipsychotics to be superior to haloperidol decanoate but equivalent to fluphenazine decanoate. Reference Conley, Kelly, Love and McMahon23

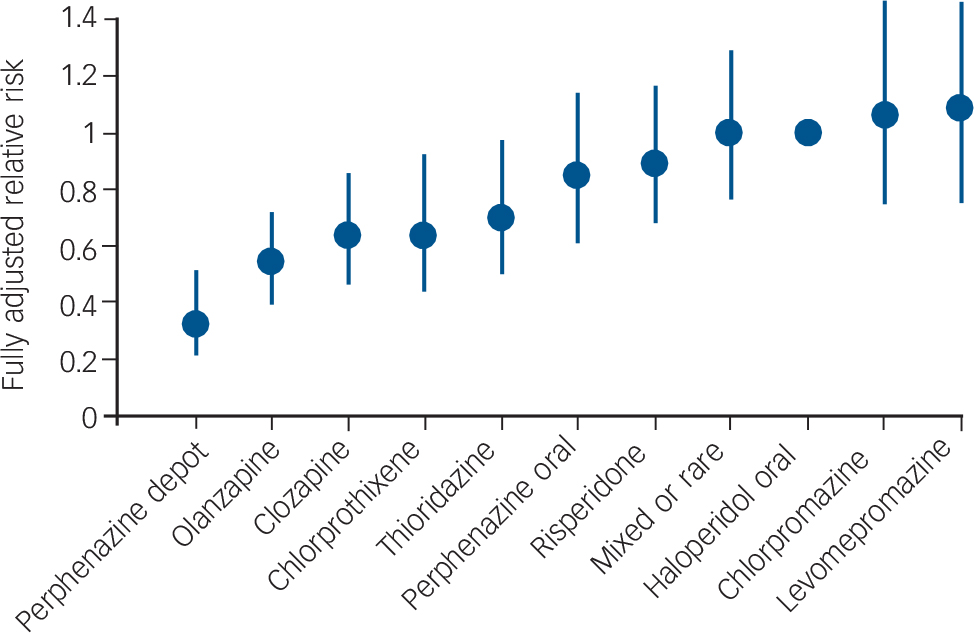

Tiihonen et al assessed the outcome of patients after their first admission with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Reference Tiihonen, Walhbeck, Lönnqvist, Klaukka, Ioannidis and Volavka19 The other studies in Table 1 had samples wholly or largely comprising patients who had had schizophrenia for several years. The Tiihonen study assessed a nationwide cohort, all first admissions in Finland occurring over a 5½-year period, and had a mean follow-up period of 3.6 years. Analysis was performed on the ten most commonly used antipsychotics, which included one injectable formulation: perphenazine LAI. Multivariate models and propensity score methods were used to adjust estimates of effectiveness, and comparisons were made with oral haloperidol. Initial use of perphenazine LAI was associated with a significantly lower adjusted risk of all-cause discontinuation than that for haloperidol and the second lowest discontinuation rate of the ten drugs studied. In an analysis of rehospitalisation rates, calculated according to the ongoing antipsychotic, perphenazine LAI had the lowest risk of rehospitalisation (68% reduction in fully adjusted relative risk compared with haloperidol) (Fig. 2). Oral perphenazine showed no difference from oral haloperidol in terms of adjusted risk of discontinuation and rehospitalisation, suggesting that it was the mode of administration rather than the drug per se that was responsible for the improved outcome with perphenazine LAI. Reference Haddad and Niaz24

Fig. 2 Risk of rehospitalisation associated with current ongoing antipsychotic compared with oral haloperidol. Vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Adjusted for gender, calendar year, age at onset of follow-up, number of previous relapses, duration of first hospitalisation, and length of follow-up by a multivariate regression and the propensity score method. From Tiihonen et al. Adapted by permission from BMJ Publishing Group (© 2006).

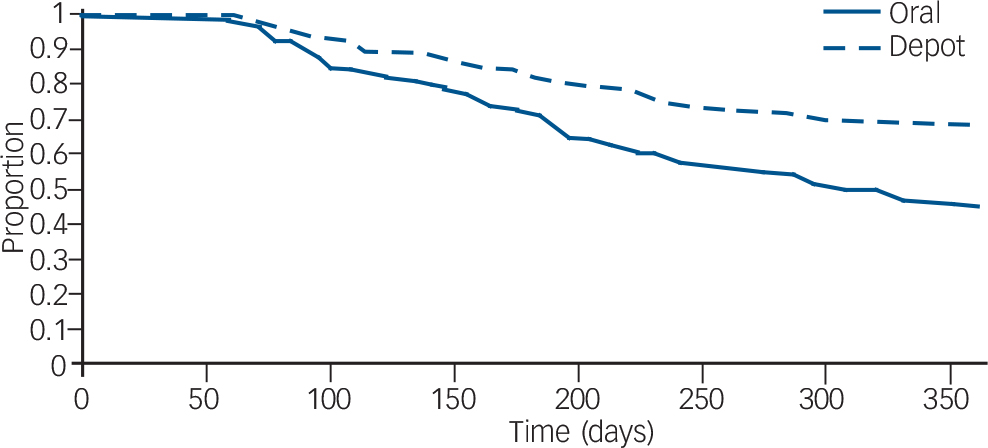

Zhu et al used data from the US Schizophrenia Care and Assessment Program (US–SCAP) study to assess the time to all-cause medication discontinuation in the first year after initiation of an FGA–LAI or oral antipsychotic. Reference Zhu, Ascher-Svanum, Shi, Faries, Montgomery and Marder20 The study assessed the same two antipsychotics – haloperidol and fluphenazine – in oral or LAI form. Compared with those treated with oral medication, those treated with LAI had a significantly longer mean time to all-cause medication discontinuation and were twice as likely to continue taking the medication (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Survival analysis of time to discontinuation for any reason of first-generation antipsychotics (injected or oral) in the first year after medication initiation. From Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Ascher-Svanum, Shi, Faries, Montgomery and Marder20 Reprinted with permission from Psychiatric Services (© 2008). American Psychiatric Association.

The SOHO study was a pan-European observational study funded by Eli Lilly that recruited over 10 000 patients with schizophrenia when they began a new antipsychotic medication regimen on an out-patient basis. Reference Haro, Novick, Suarez, Alonso, Lépine and Ratcliffe21 Patients were assessed at regular intervals for up to 3 years or until discontinuation of the baseline antipsychotic. The study included various SGA–oral cohorts plus a mixed cohort prescribed various FGA–LAIs and another mixed cohort taking various FGA–orals. Statistical comparisons were made relative to oral olanzapine. The likelihood of not achieving remission, the risk of relapse and the all-cause discontinuation rate of medication were all higher for those treated with FGA–LAI compared with oral olanzapine. Reference Haro, Novick, Suarez, Alonso, Lépine and Ratcliffe21,Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 The proportion of individuals who had stopped medication by 3 years was 36.4% for those taking olanzapine, 50.2% for those who began FGA–LAI treatment and 53.1% for those taking an oral FGA. Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 The hazard ratio (risk) for discontinuation relative to olanzapine for FGA–orals was 1.70 (95% CI 1.46–1.97) and for FGA–LAIs it was 1.43 (95% CI 1.19–1.70). Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22

Conley et al assessed the risk of readmission in patients discharged from several in-patient psychiatric units in the State of Maryland, USA. Reference Conley, Kelly, Love and McMahon23 Cohorts discharged on fluphenazine decanoate and haloperidol decanoate were compared with cohorts discharged on one of three SGA–orals. The 1-year readmission risk (with adjustment for baseline variables) for each of the three SGA–oral groups was lower than for the haloperidol decanoate group but similar to that seen with fluphenazine decanoate.

The only study in Table 1 that presented tolerability data was the SOHO study, albeit descriptive data without statistical analysis. Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 The presence of extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia was based on clinical judgement rather than rating scales. The period prevalence for extrapyramidal symptoms (present at any time during follow-up or until medication discontinuation) was 42.8% for the FGA–LAI cohort and 31.4% for the FGA–oral cohort, and within the various SGA–oral cohorts values ranged from 13.4% (quetiapine) to 32.2% (risperidone). The prevalence of tardive dyskinesia was 12.9% for the FGA–LAI cohort and 8.7% for the FGA–oral cohort, and within the SGA–oral cohorts values ranged from 5.9% (olanzapine) to 9.8% (amisulpride). Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 The proportion of patients who gained more than 7% in weight from baseline to medication discontinuation was higher for FGA–LAI than for FGA–oral (21.8% v. 15.7%), as was mean weight gain (2.6 kg v. 1.5 kg). Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22

Mirror-image studies

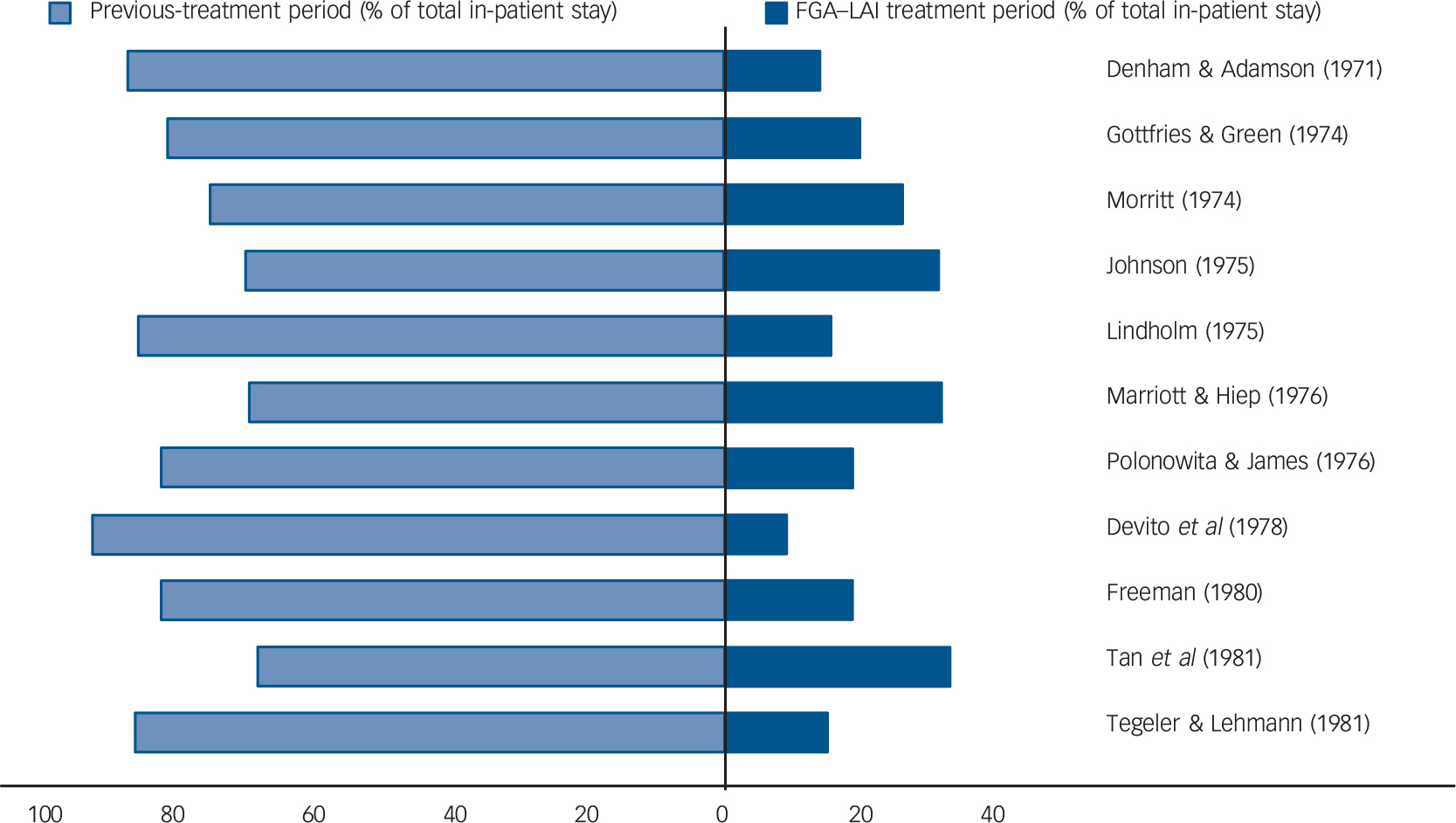

Mirror-image studies are a specific type of retrospective observational study in which a cohort of patients receiving LAIs is identified and the total number of in-patient days or admissions during LAI treatment is compared with that during an equal time period immediately preceding LAI initiation. For each patient, the duration of treatment on LAI and the duration of the preceding period are the same, i.e. each patient acts as their own comparator. Our search identified eleven mirror-image FGA–LAI studies. Reference Denham and Adamson25–Reference Tegeler and Lehmann35 In each study, total in-patient days and number of admissions were lower on FGA–LAI than during the preceding treatment period, and where P-values were available or could be calculated the differences were statistically significant (Table 2, Fig. 4). Based on the 10 studies with specific in-patient data, the mean number of in-patient days per patient fell from 114.9 in the pre-FGA–LAI period to 28.6 during FGA–LAI treatment (Table 2).

Fig. 4 Distribution (%) of total in-patient stay between previous treatment and first-generation antipsychotic long-acting injection (FGA–LAI) treatment periods for each of 11 mirror-image studies. Reference Denham and Adamson25–Reference Tegeler and Lehmann35 Each horizontal bar is equivalent to 100%.

Other retrospective observational studies

We identified two retrospective observational studies that compared two different patient cohorts, one treated with an FGA–LAI and one with oral medication (Table 3). Reference Devito, Brink, Sloan and Jolliff32,Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 The readmission rate was lower in the FGA–LAI group in one study, Reference Devito, Brink, Sloan and Jolliff32 butdid notdiffer between LAI and oral medication in the other. Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 One of the two studies provided tolerability data. Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 Baseline anticholinergic drug use was similar, but during the subsequent 2 years anticholinergic drugs were prescribed more frequently to the patients given injections than to those prescribed an oral drug (47% v. 13%, P = 0.01).

Discussion

Randomised controlled trials

Adams et al interpreted the equivalent relapse rates and tolerability of LAIs and oral medication in their meta-review (see Fig. 1) as indicating that FGA–LAIs were well tolerated and effective. Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12 The lack of difference in relapse rates is a robust finding given the large sample (n = 848), the narrow confidence interval and the fact that most included studies had a duration in excess of 1 year. However, RCTs are likely to selectively recruit adherent patients, resulting in a bias towards finding no difference between the oral and LAI arms. For example, RCTs often exclude patients with comorbid substance misuse, which is strongly associated with poor adherence. Reference Cooper, Moisan and Grégoire37,Reference Hudson, Owen, Thrush, Han, Pyne and Thapa38 Adams et al acknowledged this bias, commenting: ‘Those for whom depots (LAIs) are most indicated may not be represented’. Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12 Furthermore, in double-blind trials of long-acting injections v. oral medication, the oral treatment group receive placebo injections in addition to active oral medication to preserve study masking. Reference Chouinard, Annable and Steinberg39 The placebo injection and associated regular staff contact are both absent in the usual care of patients taking oral medication and may enhance the outcome of the oral cohort.

Adams et al found that global clinical improvement was twice as likely in the FGA–LAI group than in the FGA–oral group (see Fig. 1). Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12 This may reflect partial adherence to oral medication, i.e. the rate of non-adherence with oral medication was not high enough for the oral group to show a higher relapse rate than the LAI group (as might have been expected) but was sufficient to undermine symptom control.

Prospective observational studies

Observational studies have several advantages over RCTs in that they include ‘real world’ patients, can assess large populations, have long follow-up periods and clinically relevant outcome measures and are financially cheaper to conduct. Their main weakness is the lack of randomisation, which means that selection bias and not allocated treatment may account for outcome. This is a particular problem when LAIs are compared with oral antipsychotics, as the individual characteristics of patients prescribed these two treatments often differ. Shi et al used data from the US–SCAP study to compare the characteristics of patients starting an FGA–LAI with those starting an SGA–oral or FGA–oral. Reference Shi, Ascher-Svanum, Zhu, Faries, Montgomery and Marder2 Independent factors that predicted use of an LAI over oral medication included more severe psychotic symptoms, a higher rate of psychiatric hospitalisation in the previous year, a higher rate of current substance misuse, and a higher likelihood of being African American and having a history of arrest. Selection bias means that patients treated with an LAI would be expected to have a worse outcome than those treated with oral medication even if treatments were equally effective. Observational studies usually employ statistical techniques to correct for baseline variables, for example multivariate analysis and propensity scoring, but these may not adequately adjust for the selection bias if unknown or unmeasured variables affect outcome.

The two prospective studies in which FGA–LAI was superior to oral medication used an FGA–oral comparator, Reference Tiihonen, Walhbeck, Lönnqvist, Klaukka, Ioannidis and Volavka19,Reference Zhu, Ascher-Svanum, Shi, Faries, Montgomery and Marder20 whereas the two studies that showed a worse outcome for FGA–LAIs selected an SGA–oral comparator (Table 1). Reference Haro, Novick, Suarez, Alonso, Lépine and Ratcliffe21,Reference Conley, Kelly, Love and McMahon23 The conflicting results may be because selection bias is greater when comparing between formulation (oral or LAI) and simultaneously between class (FGA or SGA). Consistent with this, outcomes in the SOHO study appeared similar for the FGA–LAI and FGA–oral cohorts (P-values not provided). Reference Haro, Novick, Suarez, Alonso, Lépine and Ratcliffe21 In the study by Conley et al outcomes did not differ significantly between fluphenazine decanoate and SGA–orals, whereas haloperidol decanoate was inferior to SGA–orals. Reference Conley, Kelly, Love and McMahon23 This may reflect the poorer tolerability of haloperidol decanoate compared with fluphenazine decanoate.

Mirror-image studies

We identified 11 mirror-image studies (see Table 2) in contrast to the 6 mirror-image studies identified in an earlier review of FGA–LAIs by Davis et al. Reference Davis, Matalon, Watanabe and Blake40 Although these studies consistently showed reduced in-patient care after switching to an LAI, methodological issues mean that this cannot be accepted as categorical evidence that LAIs are superior. It is well recognised that mirror-image studies can be confounded by independent events that occur during the study, for example a reduction in hospital beds or the introduction of improved community support. Reference Davis, Matalon, Watanabe and Blake40 In addition, admission length can be influenced by non-clinical factors such as the availability of discharge accommodation. Mirror-image designs have other methodological weaknesses that have been largely neglected in the literature. These include an inherent bias towards improvement, the issue of how ‘index admissions’ are analysed for those who begin LAI treatment as in-patients, and selection of LAI responders. These issues are discussed further in this section.

Mirror-image studies have an inherent design bias, namely that the initial treatment (in this case oral medication) ends with treatment failure, otherwise the second medication (in this case an LAI) would not be commenced. If the reason for switching is lack of efficacy rather than intolerability, then subsequent improvement in terms of admissions or bed-days could represent natural remission (i.e. a regression to the mean effect) rather than the superiority of a new medication. Hospital admission for people with schizophrenia is especially liable to regression to the mean because it represents extreme decompensation in a chronic fluctuating illness.

Another methodological issue, for those who start LAI treatment as an in-patient, is how the index admission (i.e. the admission during which LAI is started) is analysed. This is important, as a high proportion of LAI patients begin treatment as in-patients. As the index admission results from failure of the preceding oral medication, the initial assumption is to attribute it to prior treatment. However, the duration of the index admission may be lengthened when switching to an LAI as opposed to an oral antipsychotic, owing to the need for a test dose with FGA–LAIs and the longer time required to achieve a therapeutic plasma level. Three ways of analysing the index admission exist: exclude it from analysis (this may introduce a bias against the LAI); allocate it totally to prior treatment (this may introduce a bias in favour of the LAI); or divide it between the two treatments according to the start date of the LAI (a compromise between the two previous methods of analysis). There is no right or wrong way to analyse the index admission and different researchers have taken different views. Of the 11 mirror-image studies we reviewed, 5 excluded the index admission, 2 divided it between preceding treatment and LAI, and the remaining 4 studies did not specify the approach adopted. We recommend that future mirror-image studies are explicit about how the index admission is analysed.

Some mirror-image studies select LAI responders by restricting analysis to those who have completed a minimum length of LAI treatment rather than considering all those who started an LAI during a defined period. Seven of the 11 studies we identified assessed those who had completed at least 12 months of LAI treatment, and a further study included only those who had completed 2 years of LAI treatment (see Table 2). Reference Tan, Ong and Chee34

Other retrospective observational studies

Of the two retrospective studies with a separate oral comparator group, matching was attempted in one. Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 However, this study was limited by the patients being highly selected, unrepresentative and biased towards an adherent group. Entry criteria included completing 2 years of treatment on the same drug and no Axis I diagnosis other than schizophrenia. This meant that patients with comorbid substance misuse – a predictor of poor adherence Reference Cooper, Moisan and Grégoire37,Reference Hudson, Owen, Thrush, Han, Pyne and Thapa38 and rehospitalisation Reference Olfson, Mechanic, Boyer, Hansell, Walkup and Weiden41 – were excluded. These factors may contribute to the finding of comparable readmission rates for oral medication and LAI. Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 The other study in this category found a lower readmission rate for patients on LAI compared with those on oral medication. Reference Devito, Brink, Sloan and Jolliff32 However, the small sample (n = 61 in each arm) and lack of randomisation mean that the result needs to be viewed with caution.

Tolerability

There was a scarcity of reported tolerability data. Most related to extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia, but only the prevalence rate for tardive dyskinesia in the meta-analysis by Adams et al was based on the use of objective rating scales. Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12 Two studies used the prescription of anticholinergic drugs as a marker for extrapyramidal symptoms, Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12,Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 and in the SOHO study the presence of extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia was based on clinical judgement. Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 Three period prevalence rates (maximum duration of 3 years) for extrapyramidal symptoms in patients on FGA–LAI were available: 42.8% in the SOHO prospective study, Reference Haro, Novick, Suarez, Alonso, Lépine and Ratcliffe21,Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 47.0% in a retrospective case-note study, Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 and 69.5% in a meta-analysis. Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12 Two period prevalence rates (maximum duration 2 years) were available for tardive dyskinesia: 9.0% in a meta-analysis and 12.9% in the SOHO study. Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12,Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 Despite the methodological limitations, these prevalence rates are high, possibly reflecting a high use of haloperidol LAI in two studies. Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22,Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 The only study to make a statistical comparison between rates of extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia in patients prescribed FGA–LAI and FGA–oral drugs was that by Adams et al, and the rates were comparable. Reference Adams, Fenton, Quraishi and David12

Two observational studies, the SOHO study and that by Marchiaro et al, reported higher rates of extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia in a cohort prescribed various FGA–LAIs than in patients prescribed SGA–oral drugs. Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22,Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 This suggests that SGAs may be associated with a lower incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia than some FGA–LAIs (haloperidol LAI was the predominant LAI in the study by Marchiaro et al, Reference Marchiaro, Rocca, LeNoci, Longo, Montemagni and Rigazzi36 and the breakdown of LAIs in the SOHO study is not given.) Reference Haro, Suarez, Novick, Brown, Usall and Naber22 Future studies should compare the extrapyramidal symptoms liability of specific drugs rather than make generalisations about SGAs and FGAs as the risk varies between different drugs within both respective groups. Reference Haddad and Sharma42 A recent meta-analysis showed that all SGAs were associated with much fewer extrapyramidal symptoms than haloperidol, but the advantage was either absent or much less apparent in a comparison with low-potency FGAs. Reference Leucht, Corves, Arbter, Engel, Li and Davis43 In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) and Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia Study (CUtlASS) trials, Reference Lieberman, Stroup, McEvoy, Swartz, Rosenheck and Perkins44,Reference Jones, Barnes, Davies, Dunn, Lloyd and Hayhurst45 the prevalence of extrapyramidal symptoms did not differ between SGAs and the FGA comparator – perphenazine in CATIE, Reference Lieberman, Stroup, McEvoy, Swartz, Rosenheck and Perkins44 and various FGAs (but predominantly sulpiride) in CUtlASS. Reference Jones, Barnes, Davies, Dunn, Lloyd and Hayhurst45

Conclusions and future research

Randomised controlled trials and observational studies have different strengths and weaknesses, and reviewing them alongside each other as in this systematic review provides the most comprehensive assessment. Overall we found variable and inconclusive results. The four study designs we considered (RCTs, prospective observational studies, mirror-image studies and other retrospective studies) all showed some evidence of better outcome with FGA–LAIs than with oral antipsychotic medication, but some studies showed the converse or no difference between the two groups. The variability in results may partly reflect methodological issues. Selective recruitment into RCTs and lack of randomisation in observational studies can bias against LAIs, whereas regression to the mean in mirror-image studies can favour LAIs. Overall the results suggest that FGA–LAIs may have a benefit over oral medication but this is far from conclusive.

Given these inconclusive results, a pragmatic RCT comparing an oral antipsychotic drug and an FGA–LAI would be of value. The primary outcome should be relapse (operationally defined) and the trial should be of sufficient duration to assess this. Secondary outcome measures could include symptomatic improvement, a range of adverse effects (including extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, weight gain and metabolic parameters), user satisfaction and cost-effectiveness. It would be important to recruit patients at risk of relapse in whom antipsychotic adherence has been poor, because this is the primary group for whom clinicians consider using LAIs. Exclusion criteria should be minimal. Such a trial is relevant as FGA–LAIs remain widely prescribed and recent pragmatic RCTs, including CATIE and CUtLASS, Reference Lieberman, Stroup, McEvoy, Swartz, Rosenheck and Perkins44,Reference Jones, Barnes, Davies, Dunn, Lloyd and Hayhurst45 have shown similar outcomes for oral FGAs and oral SGAs other than clozapine.

There are accumulating data from long-term RCTs of SGA–LAIs v. oral medication. Reference Keks, Ingham, Khan and Karcher46–Reference Citrome49 This allows for an updated meta-analysis that compares both FGA–LAIs and SGA–LAIs with oral antipsychotics. Future research could also compare an FGA–LAI with an SGA–LAI; in theory a single trial could compare an FGA–LAI, an SGA–LAI and an oral antipsychotic.

The high prevalence rates of extrapyramidal symptoms (43–70%) and tardive dyskinesia (9–13%) reported over periods up to 3 years with FGA–LAIs emphasises the importance of screening patients regularly for extrapyramidal symptoms, although in practice this is often neglected. Reference Mitra and Haddad50,51 Screening should cover a full range of potential adverse effects, including weight gain and metabolic abnormalities, and ideally occur in a systematic manner using a practical but valid scale. Reference Waddell and Taylor52

Current guidelines recommend that long-acting injections be considered for patients with schizophrenia who adhere poorly to oral medication regimens and for patients who express a preference for this treatment. Reference Kane, Leucht, Carpenter and Docherty53–57 Despite the inconclusive results of our review we support these recommendations. Even if LAIs do not reduce relapse rates beyond those seen with oral medication, they prevent covert non-adherence, which is beneficial. Reference Barnes and Curson58 The decision to use an LAI should be made on an individual patient basis, usually as a joint decision by the clinician and patient. Long-acting injections can only lead to improved outcomes if a patient is committed to this form of treatment.

Acknowledgement

We thank Andrew Bradley, Eli Lilly, for creating Fig. 2 from data in the corresponding paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.