In this article, I show that two faces of sexism—hostile and benevolent—operate differently to shape Americans’ electoral decisions and evaluations of their leaders. Drawing on a nationally representative survey that included measures of Americans’ views of their congressional candidates and members of Congress, plus a conjoint experiment using fictitious candidates, I show that hostile sexism increases support for men and opposition to women. On the other hand, benevolent sexism—a subjectively positive yet disempowering reaction to traditional women—operates symbolically: it increases support for traditional masculine leadership styles and opposition to feminine styles, regardless of the leader’s actual sex. Because political science research on sexism in American politics has focused primarily on its hostile face, we have only a partial understanding of the ways that sexism shapes candidate evaluations and voting behavior. We have missed, in particular, the ways that symbolically gendered political styles engage benevolent sexism.

After explicating the concepts of hostile and benevolent sexism and briefly discussing the prominent place of gender in modern American politics generally and in the 2016 election specifically, I draw on unique, nationally representative survey data to demonstrate the importance of both faces of sexism for voter decision-making at the presidential and congressional levels. I present three empirical analyses. The first shows that both faces of sexism led voters to favor Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton, with a combined impact rivaling those of racism, partisanship, and economic anxiety. The second analysis demonstrates that hostile sexism shaped congressional evaluations as well: hostile sexist voters were less favorable toward women and more favorable toward men who were running for or serving in Congress. Surprisingly, in this analysis, benevolent sexism did not matter at all.

The third analysis deploys a conjoint experiment to explain this surprise and to unpack the different political-psychological mechanisms by which hostile and benevolent sexism operate. I found that hostile sexism’s impact was moderated by the candidate’s sex, as it was in the observational analyses: it generated opposition to women and support for men. In contrast, benevolent sexism was moderated by candidates’ gendered leadership styles but not by their sex. Benevolent sexists opposed candidates with collaborative and cooperative (i.e., feminine) styles and favored candidates with decisive and forceful (i.e., masculine) styles, regardless of whether the candidate was male or female. Benevolent sexism shaped reactions to symbolically masculine and feminine traits or leadership styles. This impact came through clearly in the experiment, in which I randomly assigned candidate sex and gendered style; it was obscured in the observational analysis because it lacked measures of candidates’ leadership styles.

Politics and Gender in 2016

The gendered focus of the 2016 presidential contest grew out of long-standing American debates about gender and men’s and women’s roles. Anti-feminist activism and the defense of traditional gender norms played an important role in the modern conservative movement (Spruill Reference Spruill, Schulman and Zelizer2008), and feminist and anti-feminist groups became central to the Democratic and Republican coalitions, respectively. Reviewing these developments, Wolbrecht (Reference Wolbrecht2000, 6) concludes that on gender issues, the partisan “lines have thus been drawn with considerable clarity since 1980.” This led ordinary citizens, in turn, to think of the two parties in gendered terms (Winter Reference Winter2010).

The 2016 presidential campaign built on these associations. Hillary Clinton has long embodied changing gender roles in the family, society, and politics, beginning with her role as first lady and reinforced by her roles as secretary of state and U.S. senator, by her candidacy in the 2008 Democratic primary, and especially by her nomination as the first woman to represent a major party. On the other side, Donald Trump enacted a particularly aggressive masculine dominance, while also emphasizing the vulnerability of men and male authority to feminist threat (Johnson Reference Johnson2017). He linked male power with the power of the state (Smirnova Reference Smirnova2018) and conflated political power with masculine dominance over women and over other men (Pascoe Reference Pascoe2017). And, of course, Trump has a long history of sexist remarks and accusations of sexual harassment and assault (Cohen Reference Cohen2017), while at the same time claiming to “cherish” women—a combination that perfectly reflects the mixture of hostile and benevolent sexism (Glick Reference Glick2016). Finally, gender and sexism featured prominently on the public agenda in 2016, a year that saw Roger Ailes’s resignation from Fox News amid sexual harassment allegations by Gretchen Carlson and others; the arrest of Bill Cosby on rape charges in late 2015; the lenient sentencing for rape of Stanford student Brock Turner;Footnote 1 and the continuing controversy over a retracted Rolling Stone article about rape at the University of Virginia.

The Two Faces of Sexism

Glick and Fiske (Reference Glick and Fiske1997, 120) argue “that sexism is fundamentally ambivalent, encompassing both subjectively benevolent and hostile feelings toward women.” This combination, they say, is rooted in “the basic structure of gender intergroup relations. . . a curious combination of power difference and intimate interdependence… . this seemingly peculiar (though not unique) combination creates hostile and benevolent ideologies about both men and women” (Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske2001, 115–16). As Burns and Gallagher (Reference Burns and Gallagher2010, 427) describe, gender is “managed by role segregation mixed with intimacy. . . gender is a hierarchy we often perpetuate in our families, with people we love, not just strangers and acquaintances. It is a hierarchy accommodated by those at the bottom, by women themselves.” That is, the combination of hierarchy and interdependence produce contrasting stereotypes and emotional reactions: on the one hand, warm feelings toward women who are seen as moral and pure, yet weak and needing male protection; on the other hand, cold feelings toward women who reject this traditional arrangement between the sexes. Glick and Fiske call this “ambivalent sexism,”Footnote 2 which comprises hostile sexism, an antagonistic reaction to women who seek power or threaten the gender status quo, plus benevolent sexism,Footnote 3 “a subjectively positive orientation of protection, idealization, and affection directed toward women” who accept traditional power arrangements and enact a conventional gender role (Glick et al. Reference Glick2000, 763).

Benevolent sexism, say Glick and colleagues, encompasses three interrelated beliefs: complementary gender differentiation, the belief that women and men have fundamentally different and complementary traits, roles, and inclinations; heterosexual intimacy, the conviction that women should provide intimacy and support to men; and protective paternalism, the belief that men can and should protect women. Hostile sexism is directed at women who do not play their part—that is, at women who have or seek power over men, who deny men intimate access, or who infringe on male authority.Footnote 4 Thus, hostile and benevolent sexism together produce polarized evaluations women: positive toward “good women” who deserve protection because they are moral and pure and defer to men, and negative toward “bad women” who are seen as deserving punishment for threatening gender hierarchy. This “Madonna/whore” dichotomy has deeps roots in Western society, from ancient Greek depictions of women (Pomeroy Reference Pomeroy1975) through modern media and cultural representations (e.g., Macdonald Reference Macdonald1995).

Gender, of course, includes much beyond a binary distinction between male and female. In contrast with “sex” or “sex category,” gender encompasses the psychological, social, and cultural aspects of identity and behavior that mark a person as masculine or feminine. “Virtually any activity can be assessed as to its womanly or manly nature,” write West and Zimmerman (Reference West and Zimmerman1987, 136), and political leadership is no exception (Conroy Reference Conroy2015; Heldman, Conroy, and Ackerman Reference Heldman, Conroy, Ackerman, Heldman, Conroy and Ackerman2018; Parry- Giles and Parry-Giles Reference Parry-Giles and Parry-Giles1996; Cooper Reference Cooper2008). The two faces of sexism work together to enforce a particular set of expectations for how women enact their gender; in so doing, they justify gender inequality and a traditional gendered division of labor. Hostile sexism is the “iron hand” that punishes women, such as feminists or “career women,” who violate gender prescriptions, while benevolent sexism serves as the “velvet glove” that rewards women who remain morally pure and subordinate (Jackman Reference Jackman1994). The political impact of this velvet glove it illustrated by Becker and Wright’s (Reference Becker and Wright2011, 62) finding that exposure to “benevolent sexism undermines and hostile sexism motivates collective action for social change” among women.

Hostile sexism is directed especially at nonconforming women (Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske1996), while benevolent sexism is closely connected with the regulation and evaluation of how women—and, as I discuss later, men—enact gender by shaping “evaluations of women based on whether or not they fit the traditional, sexually pure, virtuous female” (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Fiske, Glick and Chen2010). Abrams and colleagues’ research on reactions to rape demonstrates the distinct yet complementary roles of the two faces of sexism. They found that men’s hostile sexism predicted proclivity toward committing acquaintance rape, but only in a scenario in which the woman was seen as violating chastity norms by wanting sex or “leading on” a man. Men and women high in benevolent sexism both blame an acquaintance-rape victim who initially wanted sex or was engaging in infidelity, again based on the perception that she lacked feminine virtue. On the other hand, benevolent sexism was unrelated to victim blame in a stranger-rape scenario in which nonconsent was unambiguous (Abrams et al. Reference Abrams, Viki, Masser and Bohner2003; Viki and Abrams Reference Viki and Abrams2002). Moreover, benevolent sexism predicted less blame and shorter sentence recommendations for the perpetrators in acquaintance—but not stranger—rapes (Viki, Abrams, and Masser Reference Viki, Abrams and Masser2004).

Benevolent sexism shapes reactions to other aspects of gender performance. Herzog and Oreg (Reference Herzog and Oreg2008) found that participants recommend shorter sentences for women who conform to traditional roles than for men and nontraditional women. Several studies show that benevolent sexism is associated with valorizing (and enforcing) traditional motherhood norms. For example, benevolent sexism predicts endorsement of behavioral rules for pregnant women, while hostile sexism predicts punitive attitudes toward women who do not follow them (Murphy et al. Reference Murphy, Sutton, Douglas and McClellan2011). Also, benevolent sexism is associated with approving of breastfeeding in private and disapproving of it in public (Acker Reference Acker2009), illustrating how it works simultaneously to valorize motherhood and to consign it to the private sphere.

Benevolent sexism also affects evaluations of men, shaping reactions to the ways that they enact the protector role (Glick and Fiske Reference Glick and Fiske1999; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Fiske, Glick and Chen2010). Saucier and colleagues (Reference Saucier, Stanford, Miller, Martens, Miller, Jones, McManus and Burns2016) show that benevolent sexism predicts endorsement of “masculine honor beliefs” that require men to retaliate for insults to their honor, and Viki, Abrams, and Hutchinson (Reference Viki, Abrams and Hutchison2003) show that benevolent—but not hostile—sexism is related to endorsement of “paternalistic chivalry beliefs.” These interlinked expectations for women and men together generate a chivalric “logic of masculinist protection” (Young Reference Young2003) with distinct gender scripts: good (masculine) men are strong and sacrifice to protect and provide; good (feminine) women defer to male authority in return for the protection they are thought to need.

Though hostile and benevolent sexism originate in the dynamics of the heterosexual nuclear family, they have implications beyond. For example, Cikara et al. (Reference Cikara, Lee, Fiske, Glick, Jost, Kay and Thorisdottir2009) show that hostile and benevolent sexism work together to obstruct women in the workplace. Hostile and benevolent sexism, with their focus on questions of power, legitimate authority, and deference, are also well positioned to shape political perceptions. We know very little, however, about how hostile and benevolent sexism shape reactions men and women in the most public of spheres: electoral politics.

Expectations

Hostile sexism is directed at women who seek or wield power, and a number of analyses have shown that hostile sexism powerfully shaped presidential voting in 2016 (Schaffner, MacWilliams, and Nteta Reference Schaffner, MacWilliams and Nteta2018; Valentino, Wayne, and Oceno Reference Valentino, Wayne and Oceno2018; Frasure-Yokley Reference Frasure-Yokley2018; Bock, Byrd-Craven, and Burkley Reference Bock, Byrd-Craven and Burkley2017; Bracic, Israel-Trummel, and Shortle Reference Bracic, Israel-Trummel and Shortle2019; Setzler and Yanus Reference Setzler and Yanus2018; Ratliff et al. Reference Ratliff, Redford, Conway and Smith2018; Cassese and Barnes Reference Cassese and Barnes2019) and congressional voting in 2018 (Schaffner Reference Schaffner2022). In line with this work, I expect that female candidates will elicit disapproval from those high in hostile sexism and support from those low in hostile sexism. I expect this to hold both at the presidential level and down-ballot.Footnote 5

The electoral role of benevolent sexism is less well studied, and it is not obvious what net impact it will have. On the one hand, it could simply generate opposition to women holding political power, reinforcing the impact of hostile sexism. On the other hand, because benevolent sexism involves subjectively positive feelings toward women, it might generate support for female candidates. Ratliff and colleagues (Reference Ratliff, Redford, Conway and Smith2018) found that benevolent sexism did not affect the presidential vote in 2016 after controlling for hostile sexism and ideology. On the other hand, Gervais and Hillard (Reference Gervais and Hillard2011) found that benevolent sexism—more than hostile sexism—predicted favorability toward Sarah Palin in 2008, due, they argue, to the traditional feminine connotations of her “hockey mom” image. Intriguingly, Cassese and Holman (Reference Cassese and Holman2019, 55) found that benevolent sexism was associated with approving of Clinton, but only among those aware of Trump’s explicitly sexist “playing the woman-card” attack, “consistent with benevolent sexism’s focus on protecting women.” These studies raise the prospect of a more subtle role for benevolent sexism in electoral judgments.

Benevolent sexism shapes reactions to women’s and men’s perceived adherence to traditional gender prescriptions. Thus, benevolent sexists blame women for acquaintance rape insofar as they see them as unchaste, sentence nontraditional women more heavily, valorize private motherhood, judge men on their success as providers, and so on. More broadly, Feather (Reference Feather2004, 7) found that benevolent—but not hostile—sexism is correlated with endorsement of the values of “respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas provided by traditional culture or religion.” Jost and Kay (Reference Jost and Kay2005) show that that experimental exposure to benevolent sexism increases system justification, a finding that Lee and colleagues (Reference Lee, Fiske, Glick and Chen2010, 585) say “provides another link between [benevolent sexism] and a desire to maintain the status quo.”

Thus, benevolent sexism is attuned to the way people enact the traditional gendered expectations associated with the context of their behavior. In most research on benevolent sexism, studies cue a context of direct interactions between literal men and women; in other words, they prime attention to the fit between women’s and men’s behavior and traditional role expectations for interpersonal interactions. This ensures that judgment turns on the fit between the sex each protagonist and gendered expectations—that is, women who enact or fail to enact female gender roles, and men who enact or fail to enact male gender roles in a scenario involving sex, gender, heterosexual intimacy, and/or sexual violence.

In contrast, work on gender stereotypes in voting shows that candidate sex is often not salient in electoral contexts, even in the presence of female candidates. Traditional gender stereotypes of “women” are often irrelevant to candidate evaluation below the presidential level (Brooks Reference Brooks2013; Hayes and Lawless Reference Hayes and Lawless2015, Reference Hayes and Lawless2016); more influential are stereotypes about “politicians” or “female politicians,” both of which are quite distinct from those of “women” (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2013).

Nevertheless, American political leadership carries strong symbolic associations with male patriarchal authority and protective masculinity, dating to the founding and very much still with us today (Kann Reference Kann1998; Conroy Reference Conroy2015). If benevolent sexism attends to the fit between gendered norms and the style or mode of behavior—rather than to sex per se—then it may shape evaluations based on how leaders enact a symbolically masculine political role, rather than whether they are men or women. In other words, benevolent sexism focuses on the fit between context and gendered norms; in electoral politics, those norms are masculine regardless of the sex of the candidate.

To recap, then, I expect the impact of hostile sexism to be moderated by the sex category of a candidate, increasing support for men and reducing support for women. On the other hand, I expect benevolent sexism to be engaged not by the sex of a candidate, but by the fit between a candidate’s behavior or style and the masculine norms of patriarchal political leadership. I expect those high in benevolent sexism to prefer strong, agentic leaders, and those low in benevolent sexism to reject this traditional model of leadership, preferring candidates with collaborative, symbolically feminine leadership styles. That is, I expect hostile and benevolent sexism to be moderated by literal candidate sex and by gendered political style, respectively. Finally, it is important to note that I expect opposite effects among those who are high and low in each face of sexism. Thus, my question is not whether women and/or those with feminine leadership styles are disadvantaged overall. Rather, I seek to understand individual differences, to learn about the role of both faces of sexism in voter decision-making, and thereby to explore how ideas about sex and gender infuse Americans’ perceptions of American politics both literally and figuratively.

Data

I draw on the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES), a large-scale internet survey that uses matching to achieve a nationally representative sample of American citizens over age 18 (Ansolabehere and Schaffner Reference Ansolabehere and Schaffner2018). Half of the survey is common content, asked of the full sample of 64,600 respondents; the other half is split among individual team modules that are asked of separate subsamples of respondents. My analysis draws on common content and the University of Virginia (UVa) module. YouGov conducted the survey and provided sampling weights to allow generalization to the U.S. adult population.Footnote 6 Respondents were interviewed in two waves: first before the election and again afterward.Footnote 7 The UVa module includes 1,500 respondents in the pre-election wave; of them, 1,269 (85%) also completed the post-election interview.

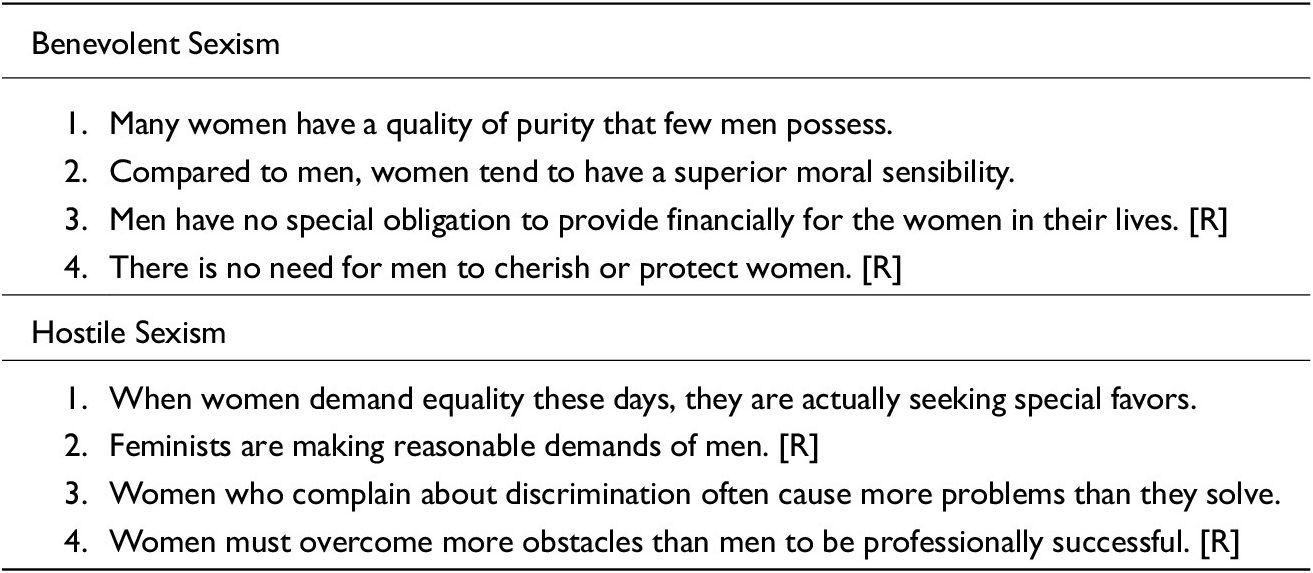

To measure sexism, I developed an eight-item battery, with four questions devoted to hostile sexism and four to benevolent sexism (see Table 1). I aimed for items with clear face validity and coverage of each construct; I also sought items that are relatively distant from politics, in order to avoid conflating sexism with support for women in politics or views on gender-relevant policy issues (see Schaffner Reference Schaffner2021). Finally, I included equal numbers of forward- and reverse-coded items to eliminate the impact of response acquiescence.

Table 1. Sexism Items

For benevolent sexism, I adapted questions from Glick and Fiske’s (Reference Glick and Fiske1996) Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI). My first two items measure complementary gender differentiation; the second two focus on protective paternalism. These items are all quite remote from politics, with their reference to men’s and women’s allegedly essential natures and to dyadic financial and protective personal relationships between the sexes.

For hostile sexism, I drew on the ASI and on Swim and colleagues’ (Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995) modern sexism scale; these two commonly used scales are conceptually and empirically interchangeable (Masser and Abrams Reference Masser and Abrams1999; Schaffner Reference Schaffner2021). The items all deal directly with questions of relative power and authority between men and women. The first two assess negative reactions to feminists and others who seek gender equality; the second two measure denial of gender inequality and discrimination. While these items are inevitably political in their mentioning of feminism, equality, and power, none directly mentions policy, and the final two arguably bring to mind a professional rather than a political context.Footnote 8

To create scales or hostile and benevolent sexism, I averaged the relevant items after reversing as needed and scaling to run from 0 (least sexist) to 1 (most sexist). Cronbach’s α for hostile sexism is 0.80, and for benevolent sexism it is 0.47. I suspect that benevolent sexism’s reliability is particularly affected by the reverse-worded items, because it involves respect for traditional authority—a trait also associated with acquiescence, or the tendency to agree with statements regardless of their content (Couch and Kenniston Reference Couch and Kenniston1960). Consistent with this, the reliabilities of the forward- and reverse-coded items, considered separately, are 0.69 and 0.67, respectively. If so, then α is artificially depressed and does not preclude the scale’s validity.Footnote 9

The Two Faces of Sexism Among the American Public

The distributions of hostile and benevolent sexism are shown in Figure 1. Americans express moderate levels of hostile sexism (mean = 0.43) and somewhat more benevolent sexism (mean = 0.57). There is good variation in both measures, with somewhat more in hostile sexism (SD = 0.24) than in benevolent sexism (SD = 0.17). They are very slightly negatively correlated (rho = −0.13).

Figure 1. Distribution of hostile and benevolent sexism

Men express more hostile sexism than women (difference of means = 0.13, p < .01), while women express a bit more benevolent sexism (difference = 0.05; p < .01).Footnote 10 As shown in Figure 2, there are sharp partisan differences in hostile sexism: Republicans average 0.28 higher than Democrats, with independents in between, although they are closer to Republicans (all pairwise differences p < .01).Footnote 11 Across partisan groups, men express more hostile sexism than women; this gender difference is largest among independents (0.16) and smaller among Republicans (0.08) and Democrats (0.09; all gender differences p < .01).

Figure 2. Mean hostile and benevolent sexism, by party identification and gender

In contrast, there are no notable partisan or gender differences in benevolent sexism.Footnote 12 Democrats, independents, and Republicans express similar levels of benevolent sexism. Among Democrats and independents, women express slightly more benevolent sexism than men (differences of 0.06 and 0.05, respectively); among Republicans, they are essentially identical. This pattern implies that appeals to benevolent sexism—even more than hostile—may have the ability to divide Democrats and draw those higher in benevolent sexism toward candidates who present an image of masculine protection.

Presidential Analysis

I begin with citizens’ views of the two major-party candidates: Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. I use several measures of voter’s reactions to them: a thermometer rating that asked respondents how warmly or coldly they feel toward each; questions asking whether each candidate had ever made the respondent feel “angry or mad” or “disgusted or sickened”; and presidential vote choice. I averaged the two emotional reactions to create an index of negative emotional reactions to each candidate.Footnote 13

Model and Control Variables

I focus on the impact of hostile and of benevolent sexism on each outcome. I include in the models a number of other predispositions that are correlated with sexism and affect these outcomes: respondents’ racial predispositions, economic evaluations, personal financial situation, partisanship, and sex category. For racial predispositions, I rely on four items included in the CCES core. Two focus on denial of racism and color-blind racial attitudes, and two assess empathy toward, or fear of, people from other racial groups.Footnote 14 I include two economic measures. The first is the average of retrospective and prospective evaluations of the economy as a whole; the second asks whether the respondent’s household income rose or fell in the past year.Footnote 15 I operationalize party identification as a pair of indicator variables for Democratic and Republican identification, and sex category as an indicator variable for female respondents.Footnote 16 Thus, my models, which I estimate using ordinary least squares (OLS), include measures of the major contending explanations for voting in 2016: sexism and gender attitudes, racism and racial attitudes, economic considerations, partisanship, and gender.Footnote 17

Results

Figure 3 shows the impact of hostile and benevolent sexism on each presidential outcome.Footnote 18 Hostile sexism has a large effect that is quite consistent across the five outcomes. Compared with those low on the scale, Americans who are high in hostile sexism rate Clinton lower (b = −0.283, p < .01) and are much more likely to express anger or disgust with her (b = 0.283, p < .01). Conversely, they rate Trump higher (b = 0.230, p < .01), are much less likely to express anger or disgust with him (b = −0.363, p < .01), and are less likely to vote for Clinton (b = −0.310, p < .01). These are large effects—for example, an otherwise average voter at the 5th percentile of hostile sexism has a probability of 0.61 of voting for Clinton, but this drops to 0.36 for a similarly average voter at the 95th percentile of hostile sexism. Conversely, of those at the 5th percentile of hostile sexism, about two-thirds report anger or disgust with Trump, compared with only 34% of respondents at the high (95th percentile) end.

Figure 3. Impact of hostile and benevolent sexism on presidential evaluations and vote

These effects are also substantial relative to the other predictors in the model: across the dependent variables, the impact of hostile sexism is about three-quarters as large as racism’s, about 80% the size of the partisan divide, and on a par with sociotropic economic evaluations (see Appendix A3 in the supplementary materials online).

Benevolent sexism also affects presidential-level evaluations, with an impact about half that of its hostile counterpart. It has the strongest effect on the expression of anger and disgust with Trump (b = −0.225, p < .01), and more moderate but still notable effects on emotional reactions to Clinton (b = 0.152, p < .05), evaluations of Trump (b = 0.157, p < .01), and vote choice (b = −0.126, p < .05). Across the models, benevolent sexism has about 40% of the impact of racism and partisanship, half that of sociotropic economic evaluations, and double that of personal finances.Footnote 19 Interestingly, benevolent sexism has little impact on thermometer ratings of Clinton. This may reflect offsetting effects: Clinton is not the sort of traditional woman whom benevolent sexists valorize, yet Trump’s attacks may have evoked paternalistic protection, consistent with Cassese and Holman’s (Reference Cassese and Holman2019) findings. Sexism’s benevolent face played a larger role in reactions to Donald Trump, with benevolent sexists perhaps especially drawn to his expressions of male dominance.Footnote 20

Congressional Analysis

I turn now to congressional voting and evaluations of members of Congress, which allows me to explore the impact of the two faces of sexism in 2016 beyond the sui generis presidential race.

Congressional Vote

In 2016, 167 women ran as major-party House candidates (120 Democrats and 47 Republicans), and 104 women were serving in Congress.Footnote 21 About a quarter of the respondents faced a female Democrat on the ballot, and 1 in 10 faced a female Republican.Footnote 22 To determine the impact of hostile and benevolent sexism on congressional vote, separately for male and female candidates, I estimated a probit model of vote choice that includes hostile sexism, benevolent sexism, each candidate’s gender, and their interactions, plus the same control variables: respondent party identification, racism, economic evaluations, personal financial situation, and sex.Footnote 23

Figure 4 presents the results for hostile sexism. The left-hand panel compares the probability of voting for a Democratic man or woman who faces a Republican man as a respondent’s hostile sexism varies from the low end to the high end of the scale. The solid line, which shows the probability of voting for a male Democrat running against a male Republican, has a moderate negative slope (probit coefficient = −0.755, n.s.); this indicates that in a race between two male candidates, respondents who are higher in hostile sexism have a slight preference for Republican candidates, holding constant respondent partisanship, racism, economic evaluations, and gender. A voter at the 5th percentile of hostile sexism has a probability of 0.54 of voting for a male Democrat; this drops to 0.40 for a voter at the 95th percentile of hostile sexism.Footnote 24

Figure 4. Impact of hostile sexism on House vote

The dashed line shows the probability of voting for a female Democrat running against a male Republican. This line is notably steeper, indicating that female candidates considerably increase the impact of hostile sexism. All else equal, voters scoring high in hostile sexism are more likely to vote against the woman; conversely, voters scoring low favor the woman.

Thus, the Democratic candidate’s sex has a substantial effect on the role of hostile sexism: the interaction term between hostile sexism and the presence of a female Democratic candidate (i.e., the difference between the two slopes) is −1.996 (p < .01). This interaction yields a net probit coefficient on hostile sexism in a race between a Democratic woman and a Republican man of −2.751—quite a bit larger than the corresponding coefficient on racism (−1.984) or economic evaluations (1.315). A voter at the 5th percentile of hostile sexism has an average probability of 0.72 of voting for a female Democrat, compared with 0.24 for a voter at the 95th percentile of hostile sexism.

Turning to Republican candidates, the right-hand panel of Figure 4 compares the probability of voting for a Republican man or woman running against a Democratic man. The solid line again represents a race with two male candidates; it is the same as on the left figure, but reversed to show the probability of voting for the Republican. The dashed line slopes downward, showing that support for Republican women decreases as hostile sexism increases. Thus, the model indicates that the presence of a female Republican candidate has a substantively large, though somewhat statistically ambiguous, impact on the role of hostile sexism. The interaction between hostile sexism and the presence of a female Republican candidate is −1.541 (two-tailed p = .097).

For the least hostile sexist voters, support for male and female Republicans is about equal. As hostile sexism increases, so does the gap in support between a female and a male candidate: for those at the 95th percentile, this gap is 26 points (0.60 versus 0.33, p = .02). In sum, voters in 2016 reacted differently to male and female candidates in a way that depended critically on their level of hostile sexism. Voters with higher levels of hostile sexism were more likely to vote against women and for men from both parties.

On the other hand, benevolent sexism had little or no impact on congressional vote choice. The left panel of Figure 5 shows the impact of benevolent sexism on support for a male or a female Democrat running against a male Republican, controlling for hostile sexism and the other variables in the model. The results are quite clear: there is no relationship. The right-hand panel presents corresponding results for the relationship between benevolent sexism and voting for a Republican man or woman facing a Democratic man. For male Republicans, there is no relationship. The dashed line implies that voters low in benevolent sexism oppose female Republicans, which is opposite of my expectations. However, the paucity of Republican women and the consequent noisiness of the estimation mean that I cannot reject the null hypothesis of no effect of benevolent sexism on vote for female Republicans;Footnote 25 therefore, I hesitate to interpret this counterintuitive finding absent additional research suggesting that it is real.

Figure 5. Impact of benevolent sexism on House vote

Approval of Current Member of Congress

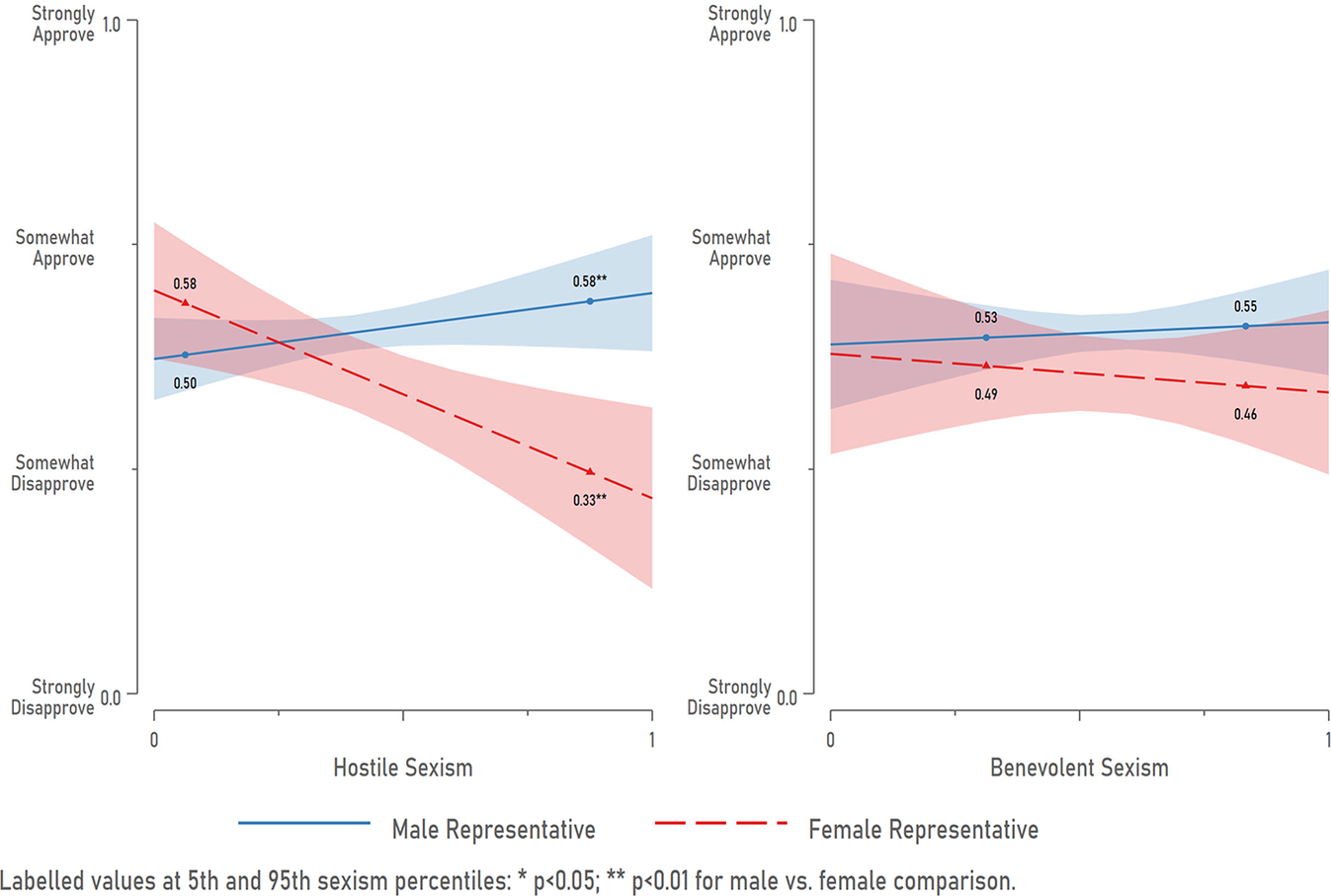

This pattern of results—candidate sex moderates hostile sexism, while benevolent sexism has no apparent effect—is replicated when I turn to congressional representative approval. Figure 6 displays results from a regression model of approval of one’s current member of Congress; this model, like that for vote choice, includes hostile and benevolent sexism, representative sex, and their interactions, plus the usual control variables and interactions between representative and respondent party identification.

Figure 6. Impact of hostile and benevolent sexism on approval of current representative

On the left panel, the solid line indicates that for male representatives, approval increases slightly with hostile sexism (b = 0.098, n.s.). The dashed line shows the relationship between hostile sexism and approval of a female representative. It slopes sharply downward: approval drops sharply as hostile sexism increases (b = −0.309, p < .01).Footnote 26 Approval of a female representative decreases from 0.58 for an otherwise average constituent with low (5th percentile) hostile sexism to 0.33 for a constituent at the high end (95th percentile). Comparing male and female representatives, we see evaluations polarizing with hostile sexism. Americans high in hostile sexism have extremely polarized views of male and female representatives: they rate women 0.25 lower than men, which is about three-quarters of the distance between “somewhat approve” and “somewhat disapprove.” And finally, the right-hand panel of Figure 6 shows that benevolent sexism continues to have no impact on approval of House members of either sex.

These congressional results are strong. Although I control statistically for other factors that influence ratings and vote, I cannot be sure that it is the sex of the representative and not some other feature of the members or the districts that makes hostile sexism loom larger for evaluations of women. Perhaps, for reasons having nothing to do with the representative, hostile sexism is simply more salient to voters in districts that happen to have female candidates and representatives. To get some leverage on this possibility, I ran three placebo models, in which I replaced the dependent variable with evaluations of President Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Hillary Clinton. Here, I do not expect an interaction between hostile (or benevolent) sexism and the sex of the congressional representative. And in fact, there is none: all interactions between having a female congressional representative and both hostile and benevolent sexism are substantively small and nonsignificant (see Table A11 in the appendix). These placebo tests are reassuring, but even more reassuring would be a true experiment.

Conjoint Experiment

I now turn to a conjoint experiment that I included in the UVA post-election module; it was completed by the 1,269 respondents in that wave. The experiment involved fictitious House candidates, which affords me two analytic opportunities. First, I test directly and replicate the interaction between candidate sex and hostile sexism. With this move, I lose some realism and external validity, but I gain experimental control and thereby strengthen causal inference. Second, I extend my analysis from candidate sex to candidate gender; that is, I experimentally vary the masculine or feminine traits that are ascribed to candidates independent of the randomly assigned sex category.

To do so, I described candidates as having a leadership approach that is either feminine (“collaborates and cooperates with others”) or masculine (“acts decisively and takes charge”). These dimensions evoke empathy and leadership, traits central to candidate evaluation (Kinder et al. Reference Kinder, Peters, Abelson and Fiske1980). They also correspond with the two fundamental dimensions of social judgment: (symbolically feminine) warmth/communality and (symbolically masculine) competence/individualism/agency (Judd et al. Reference Judd, James-Hawkins, Yzerbyt and Kashima2005).Footnote 27

Conjoint experiments, with a long history in marketing and a recent renaissance in political behavior research, facilitate analysis of the impact on voters of multiple candidate attributes. Respondents are presented with a repeated series of choices between a pair of candidates. The fundamental logic is simply that of a fully factorial experiment, with each dimension assigned randomly and independently to take one of a number of values. Conjoint experiments depart from typical political communication studies in three ways: First, they include relatively many dimensions, which increases external validity and realism, especially compared with studies that omit partisanship and other information beyond a candidate’s gender. Second, conjoint experiments randomize the features of both candidates, rather than holding one candidate constant or presenting a single candidate; this means the results are not conditioned on particular values for any of the dimensions. And third, they ask respondents to choose repeatedly between pairs of candidates, with each candidate in each pair constructed independently. This yields more information from a given number of respondents, enabling analysis of so many dimensions.

I presented respondents with information about six dimensions. Two are the focus of this analysis: candidate sex category (unobtrusively signaled by male versus female given names)Footnote 28 and their gendered legislative styles (feminine versus masculine). In addition, respondents saw four other pieces of information on each candidate: party (Democrat or Republican), legislative effectiveness (“highly effective” or “not effective”), educational prestige (“college degree” or “Ivy League degree”), and political experience (“held state-level office” or “new to politics”). Each of the 12 factors (6 per candidate) was assigned independently with equal probability for each possible value.Footnote 29

Respondents chose their preferred candidate from each of four pairs; the pairs were presented one at a time in a tabular format as shown in Figure 7.Footnote 30 Following standard practice for conjoint analysis, I estimate OLS regression models on the individual responses, clustered by respondent (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).Footnote 31 The model includes indicators for each experimentally manipulated dimension in the candidate profiles, plus interactions between candidate and respondent partisanship, and between candidate sex and traits, to allow the possibility that traits operate differently for male and female candidates.Footnote 32

Figure 7. Conjoint experiment presentation

Basic Model

I begin with a model that simply estimates the impact of each conjoint factor on candidate choice. I find that candidate sex has a small direct effect: the preference for a woman is 0.027 higher (2.7 percentage points) than for a man, and it is not statistically significant. This is consistent with prior candidate choice studies (Schwarz and Coppock Reference Schwarz and Coppock2021).Footnote 33 The ascribed traits of the candidate do have a notable effect: compared with one who “acts decisively and takes change,” respondents are 7.8 percentage points more likely to favor a candidate who “collaborates and cooperates with others” (b = 0.078, p < .01). This preference for feminine leadership is utterly unaffected by the sex of the candidate: the coefficient for the interaction between candidate sex and traits is −0.001. This baseline preference for feminine leadership in 2016 is consistent with Rachel Bernhard’s (Reference Bernhard2021) experimental evidence that California voters preferred both male and female candidates who were described as having stereotypically feminine, as opposed to masculine, leadership styles. The rest of the results also make sense: partisanship works as we would expect: partisan voters favor candidates from their own party by wide (and symmetric) margins and independents are indifferent between Democratic and Republican candidates.Footnote 34 Not surprisingly, respondents strongly prefer a candidate described as “highly effective,” by 0.265 (p < .01). Finally, prior political experience and having an Ivy League degree are irrelevant to voter choices.Footnote 35

I turn now to my central question: how do hostile and benevolent sexism shape reactions to candidates who are male versus female, and masculine versus feminine? To answer this, I add to the model respondent-level measures of hostile and benevolent sexism, plus the full set of interactions among candidate sex, candidate traits, and each sexism scale. To clarify the implications of these two- and three-way interactions, I display the results in Figure 8 for hostile sexism and Figure 9 for benevolent sexism.Footnote 36

Figure 8. Impact of hostile sexism on candidate choice (conjoint experiment)

Figure 9. Impact of benevolent sexism on candidate choice (conjoint experiment)

Sexism 1: Candidate Sex Engages Hostile Sexism

First, hostile sexism. In Figure 8, the probability of voting is indicated by the solid lines for a male candidate and by the dashed lines for a female candidate. Feminine candidates appear on the left and masculine on the right. The crossing lines indicate that the sex of the candidate conditions the impact of hostile sexism, with those high in hostile sexism favoring male candidates and those low in hostile sexism favoring female candidates. On the left, the figure shows that hostile sexism has a notable impact on support for cooperative female candidates (b = −0.113, p < .01) and essentially no impact on support for cooperative male candidates (b = 0.019, n.s.); the key test of my expectations is the difference between these two slopes, −0.132 (p = .06). The labeled probabilities at the low end of this figure indicate that a voter at the 5th percentile of hostile sexism has a probability of 0.59 of favoring a cooperative female candidate, compared with 0.52 for a cooperative male candidate (p < .05). In contrast, a voter at the 95th percentile of hostile sexism favors the cooperative man by a small margin (0.53 versus 0.50, n.s.).

This pattern, in which candidate sex conditions the effect of hostile sexism, is repeated—and sharpened slightly—for masculine candidates, in the right-hand panel of Figure 8. Here hostile sexism has a substantial positive impact on support for masculine male candidates (b = 0.120, p < .01) and a slight negative impact on support for masculine female candidates (b = −0.046, n.s.); the difference in slopes, therefore, is −0.166 (p < .01). Again, these combine to polarized reactions to male and female candidates: voters at the low end of the scale favor female candidates by 8 percentage points (i.e., with probability 0.49 for female and 0.41 for male masculine candidates, p < .01), whereas voters at the high end favor male masculine candidates by 4 points (n.s.).

Sexism 2: Candidate Gendered Traits Engage Benevolent Sexism

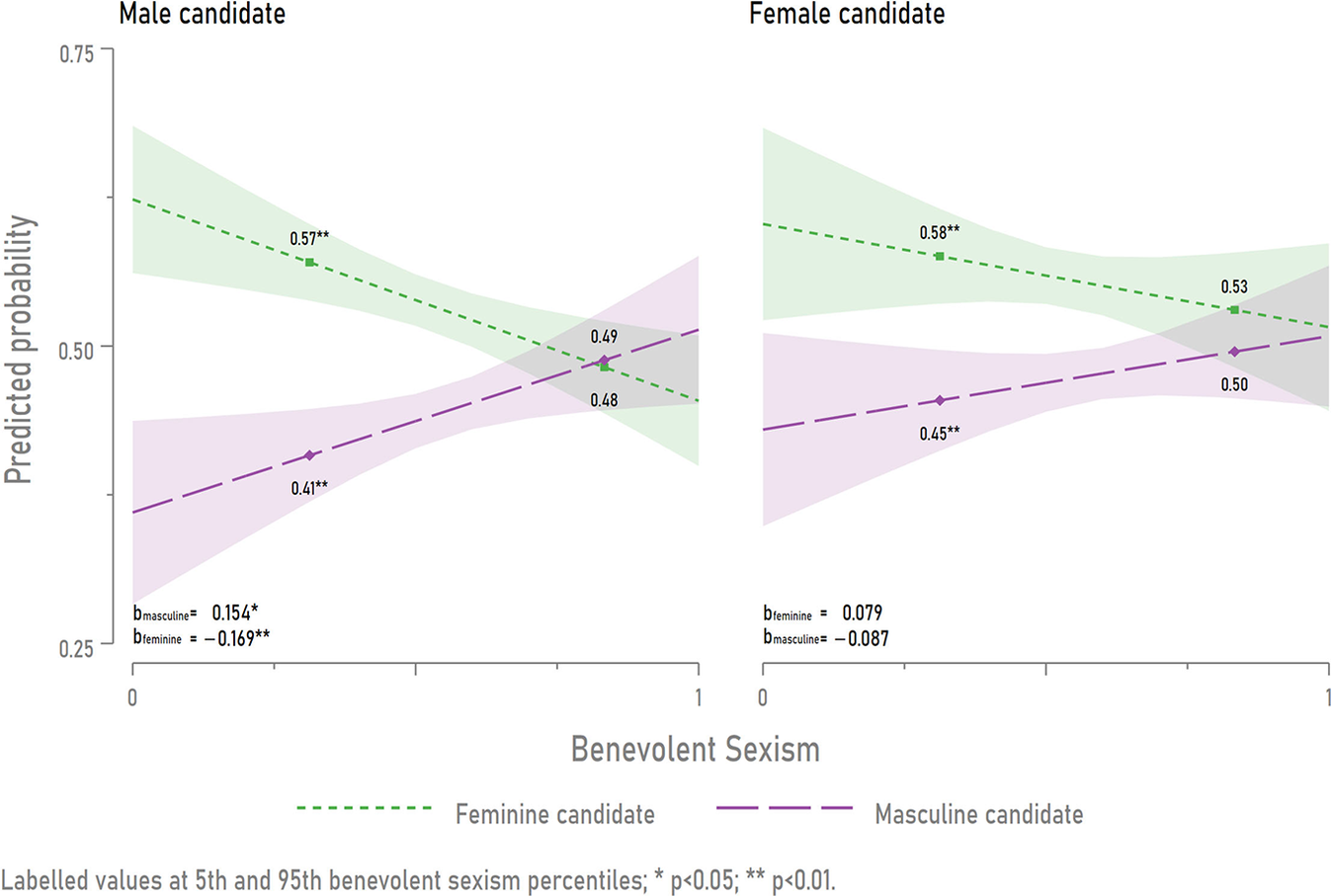

The impact of benevolent sexism is sharply conditioned by the gendered traits of the candidate, but not by candidate sex. As benevolent sexism increases, support decreases for feminine candidates regardless of sex. As shown in the left-hand panel of Figure 9, this impact of benevolent sexism is stronger for feminine male candidates (b = −0.169, p < .01) and about half as steep for feminine female candidates (b = −0.087, n.s.). In contrast, the right-hand panel shows that benevolent sexism increases support for masculine candidates, again regardless of whether they are male or female. Again, the impact of benevolent sexism is larger if the masculine candidate is male (b = 0.154, p < .05) and smaller if the masculine candidate is female (b = 0.079, n.s.).

Figure 10 shows these same benevolent sexism results, rearranged to make clearer the contrast between masculine and feminine candidates who are male (left panel) or female (right panel). For male candidates, those who are low in benevolent sexism (i.e., at the 5th percentile) have a strong preference for a feminine, collaborative candidate over a masculine, decisive one, by a margin of 16 points (57% favor the feminine man, compared with 41% favoring the masculine man).

Figure 10. Impact of benevolent sexism on candidate choice—rearranged (conjoint)

This gap narrows as sexism increases, to the point that those highest (95th percentile) in benevolent sexism are indifferent between the masculine and feminine male candidates. The right-hand panel shows a somewhat less dramatic version of the same pattern: those lowest in benevolent sexism favor a collaborative woman over a decisive woman by a margin of 13 points. Among the most benevolently sexist, this narrows to a trivial, 3-point preference for the feminine over the masculine candidate.

Thus, benevolent sexism, unlike hostile sexism, is moderated by gendered traits. This is especially true for male candidates; for female candidates, the difference in slopes in Figure 10 is somewhat more muted, though it runs in the same direction.Footnote 37

These findings are consistent with the idea that benevolent sexism involves sensitivity to gendered behavioral norms. In the modern American electoral context, the relevant norms are those associated with traditional patriarchal leadership, not those associated with the candidate’s sex.

Benevolent sexists prefer strong masculine leaders, and those low in benevolent sexism prefer non-traditional feminine leaders, whether or not the leader is a man or a woman. As I mentioned earlier, this preference for masculine over feminine leadership is somewhat stronger for male candidates than for female candidates, as shown by the steeper slopes for men than for women in each panel of Figure 10. I do not want to overinterpret this contrast, as it does not achieve statistical significance.Footnote 38 That said, it suggests that a candidate’s sex may not be entirely irrelevant for benevolent sexism. Rather, its impact is greatest when the symbolic masculine associations of the electoral context are reinforced by the literal sex category of the candidate.

This pattern is consistent with the idea that voters project their views about appropriate interpersonal power relations metaphorically onto the political realm, and that benevolent sexism is attentive to the fit between a candidate’s style and the masculine imperatives of traditional leadership. A strong, decisive leader who takes charge in the political realm is analogous to the strong, decisive husband and father who takes charge to protect his family. Benevolent sexists favor this model of leadership; those low in benevolent sexism reject this patriarchal model in the public sphere, just as they do in the intimate realm. This metaphorical projection is facilitated by male candidates, whose sex matches their role in the metaphorical political family; it is hindered (a bit) by female candidates, whose sex carries opposing gender implications.

Interesting, and consistent with this pattern, benevolent sexists prefer—and those low in benevolent sexism reject—candidates with other markers of traditional patriarchal authority. In a model with a full set of interactions (see Figures A4 and A5 and the third column of Table A13 in the appendix), I find that benevolent sexists favor candidates with prior political experience and an Ivy League education, and oppose political newcomers and those with a simple college degree. Both experience and Ivy League education—like decisiveness and the inclination to take charge—are markers of a traditional model of masculine political leadership.

Discussion and Conclusion

Social psychologists have long demonstrated that sexism encompasses two conceptually and emotionally distinct faces. My findings demonstrate that in 2016, each played an important and distinct role in shaping Americans’ reactions to presidential candidates, congressional candidates, members of Congress, and fictitious candidates who varied in their sex and gender-relevant traits. Hostile sexism powered opposition to Hillary Clinton and support for Donald Trump. Hostile sexism also motivated opposition to women and support for men at the congressional level, both observationally for actual candidates and members of Congress, and experimentally for fictitious candidates.

Benevolent sexism engendered support for Trump, and in more modest measure, opposition to Clinton. In my experiment benevolent sexism generated support for candidates who embody traditionally masculine political traits, and opposition to feminine candidates. This impact was identical regardless of the candidate’s sex. In analyzing reactions to actual congressional candidates and members of Congress, on the other hand, benevolent sexism did not play a role. The experiment explains why: benevolent sexism’s impact is moderated by a candidate’s gendered style, for which I have no measure in the observational analysis. Although candidates and members of Congress certainly vary in their gendered leadership styles, that variation is relatively independent of their sex.Footnote 39

My findings are consistent with the scholarly consensus that below the presidential level, women candidates are not hurt on average. Footnote 40 Note that the lines in the left-hand panel of Figure 4 cross very close to the average level of hostile sexism. This implies that in the aggregate, the penalty that female candidates face from sexist voters is offset by their advantage among anti-sexist voters. However, male and female candidates’ prospects will vary: in more (hostilely) sexist districts, female candidates are likely disadvantaged; in anti-sexist districts, they are advantaged vis-à-vis similarly situated men. Thus, these findings may speak to the literature on “woman-friendly districts” and the places where women are more or less likely to run and to be elected (Palmer and Simon Reference Palmer and Simon2008; Ondercin and Welch Reference Ondercin and Welch2009). These findings also have implications for debates over whether women should run “as women” or “as men.” The strategic choice to emphasize masculine or feminine leadership styles may depend more on voters’ benevolent sexism than on the candidate’s sex. In districts high in benevolent sexism, women and men should both adopt traditional masculine leadership styles; in districts low in benevolent sexism, both women and men should do the opposite.

More broadly, my benevolent sexism findings suggest an additional pathway by which gender shapes electoral outcomes. Benevolently sexist beliefs manifest politically in a commitment to traditional power hierarchies and modes of leadership that goes beyond the literal sex category of the leader. In the conjoint experiment, benevolent sexists punished candidates who did not evince the trappings of traditional symbolically masculine leadership and rewarded those who did, whether or not they were male or female. This came through clearly in the interaction with candidate traits; there was also some indication that other markers of traditional power—political experience, high-status education—also appeal to benevolent sexists. Conversely, those who reject benevolent sexism also reject this political style and other markers of traditional authority.

More broadly, these findings reflect the deeper struggle underway in the United States over political—and ultimately social and cultural—power. One face of this struggle concerns ceding power from men to women. In this context, hostile sexism is the basis for polarization, with those high in hostile sexism (men and women both) resisting female leadership and those low in hostile sexism welcoming it. A second face of this struggle reflects the place of symbolically feminine leadership styles, and on this front, benevolent sexism divides those who welcome it from those who resist it. It is worth noting that disagreement over gendered leadership styles has played an important role in recent politics. Many noted, for example, that Barack Obama brought a feminine style to his campaigns and the presidency and that this served as part of his appeal in 2008 (e.g., Cooper Reference Cooper2008; Conroy Reference Conroy2015) as well as the basis for sustained criticism of his presidency. Most broadly, these results suggest that the politics of sexism in 2016 were not restricted to the presidential race, but rather run through much of contemporary American electoral politics.

Thus, disagreement over masculine and feminine styles of leadership is relatively disconnected from disagreement about male and female leadership, with each driven by a different face of sexism. (This is especially striking given the fact that the two forms of sexism are relatively uncorrelated.) That is, citizens seem to distinguish “male” from “masculine” leadership and “female” from “feminine” leadership. These differences are consistent with other research on the relationship between hostile and benevolent sexism, on the one hand, and feelings about power relations, on the other. In my results, hostile sexism is linked with dominance by the traditionally powerful, while benevolent sexism is linked to broader ideas about proper behavior for leaders. Both Christopher and Mull (Reference Christopher and Mull2006) and Sibley, Wilson, and Duckitt (Reference Sibley, Wilson and Duckitt2007) find that hostile sexism is correlated with social dominance orientation—a tendency to endorse domination of subordinate groups by the more powerful—while benevolent sexism is correlated with right-wing authoritarianism, which involves, among other things, valorization of submission to (legitimate) authority. (Unfortunately, the 2016 CCES did not include measures of social dominance orientation or authoritarianism, so I cannot explore these connections directly.) My findings are also consistent with the idea that underlying many political conflicts through American history are moral conflicts, often powered by contestation over gender roles and the proper place of women and men in American society and politics (Morone Reference Morone2004). There is clearly room for more research about the relationships between citizens’ views about power in general (as encompassed by social dominance orientation and authoritarianism) and in the realm of gender specifically, and about how both shape and respond to election campaigns and debates over political and moral issues in American society.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X22000010.