Sleep disturbances have become quite common for the general public in modern society due to factors such as increased pace, stressful lifestyles and increased travel (Souza, Magna, & Reimao, Reference Souza, Magna and Reimao2002; Tsuno et al., Reference Tsuno, Jaussent, Dauvilliers, Touchon, Ritchie and Besset2007; Zielinski, Polakowska, Kurjata, Kupsc, & Zgierska, Reference Zielinski, Polakowska, Kurjata, Kupsc and Zgierska1998). Sleep disorders are encountered in all age groups, all societies and segments of society (Joo et al., Reference Joo, Shin, Kim, Yi, Ahn, Park and Lee2005; Kaneita et al., Reference Kaneita, Ohida, Uchiyama, Takemura, Kawahara, Yokoyama and Akashiba2005; Liu, Uchiyama, Kim et al., Reference Liu, Uchiyama, Kim, Okawa, Shibui, Kudo, Doi, Minowa and Ogihara2000; Liu, Uchiyama, Okawa, & Kurita, Reference Liu, Uchiyama, Okawa and Kurita2000; Ohayon & Lemoine, Reference Ohayon and Lemoine2004; Ohida et al., Reference Ohida, Osaki, Doi, Tanihata, Minowa, Suzuki and Kaneita2004). The prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) varies in different settings from 2 to 37% in the general population to 7 to 84% in working populations such as resident doctors, nurses, shift workers, business process outsourcing (BPO) employees and internet technology (IT) professionals (Doi, Minowa, & Futija, Reference Doi, Minowa and Futija2002; Hanlon, Hayter, Bould, Joo, & Naik, Reference Hanlon, Hayter, Bould, Joo and Naik2009; Howard, Gaba, Rosekind, & Zarcone, Reference Howard, Gaba, Rosekind and Zarcone2002; Mello et al., Reference Mello, Santana, Souza, Oliveira, Ventura, Stampi and Tufik2000; Suzuki, Ohida, Kaneita, Yokoyama, & Uchiyama Reference Suzuki, Ohida, Kaneita, Yokoyama and Uchiyama2005).

There are some segments of society where problems related to sleep primarily result from external factors, such as night-shift work, and may have a substantial impact on the productiveness of their work (Akerstedt, Reference Akerstedt2003; Defoe, Power, Holzman, Carpentieri, & Schulkin, Reference Defoe, Power, Holzman, Carpentieri and Schulkin2001; Saxena & George, Reference Saxena and George2005). The medical profession is not untouched by this malady, particularly in the case of resident doctors and nursing staff (Suzuki et al., Reference Suzuki, Ohida, Kaneita, Yokoyama and Uchiyama2005; Veasey, Rosen, Barzansky, Rosen, & Owens, Reference Veasey, Rosen, Barzansky, Rosen and Owens2002).

Long work hours are a time-honoured tradition in most residency programs in hospitals. Demanding schedules are often said to be necessary for learning and development of professionalism among doctors (Wols, Kramer, & Strange, Reference Wols, Kramer and Strange1995). The use of resident physicians to provide relatively inexpensive coverage has also become an important economical factor for teaching hospitals all over the world. In such a scenario, disturbed sleep has become an accepted norm of residency training (Defoe et al., Reference Defoe, Power, Holzman, Carpentieri and Schulkin2001; Gander, Purnell, Garden, & Woodward, Reference Gander, Purnell, Garden and Woodward2007; Howard et al., Reference Howard, Gaba, Rosekind and Zarcone2002). However, consequences of sleep problems in medical and nursing professions can have serious repercussions because of the life-saving responsibilities of these individuals (Gaba & Howard, Reference Gaba and Howard2002; Papp et al., Reference Papp, Stoller, Sage, Aikens, Owens, Avidan and Strohl2004; Veasey et al., Reference Veasey, Rosen, Barzansky, Rosen and Owens2002).

Sleepiness is commonplace among hospital staff. For example, more than 10% of resident doctors perceive sleepiness as an almost daily occurrence for themselves (Rosen, Bellini, & Shea, Reference Rosen, Bellini and Shea2004). This raises concerns about whether increased sleepiness and fatigue impair the cognitive and performance skills of resident doctors (Krueger, Reference Krueger and Bogner1994; Papp et al., Reference Papp, Stoller, Sage, Aikens, Owens, Avidan and Strohl2004). The effects of EDS on daytime functioning, cognition, memory, accidents and work errors is well studied in some countries such as the United States (US), Australia, Japan and France (Bartel, Offermeier, Smith, & Becker, Reference Bartel, Offermeier, Smith and Becker2004; Roth & Roehrs, Reference Roth and Roehrs1996, Reference Roth and Roehrs2003; Suzuki et al., Reference Suzuki, Ohida, Kaneita, Yokoyama and Uchiyama2005; Van Cauter et al., Reference Van Cauter, Holmback, Knutson, Leproult, Miller, Nedeltcheva and Spiegel2007; Webb, Reference Webb1995). However, similar studies on sleep are lacking in the Indian population.

Research in the US has shown a steady decline in the time adults spend asleep, accompanied by an estimated yearly cost to society of sleep problems ranging in the tens of billions of US dollars.(Daley, Morin, LeBlanc, Gregoire, & Savard, Reference Daley, Morin, LeBlanc, Gregoire, Savard and Baillargeon2009; Leger, Reference Leger1994; Webb, Reference Webb1995) This is creating an interest in improving sleep quality as well as sleep habits, which have been shown to improve sleep quality (Daley, Morin, LeBlanc, Gregoire, & Savard, Reference Daley, Morin, LeBlanc, Gregoire, Savard and Baillargeon2009; Daley, Morin, LeBlanc, Gregoire, Savard, et al., Reference Daley, Morin, LeBlanc, Gregoire and Savard2009; Jennum, Knudsen, & Kjellberg, Reference Jennum, Knudsen and Kjellberg2009; Kleinman, Brook, Doan, Melkonian, & Baran, Reference Kleinman, Brook, Doan, Melkonian and Baran2009; Leger, Reference Leger1994; Presser, Reference Presser1999; Vauth & Greiner, Reference Vauth and Greiner2009; Webb, Reference Webb1995).

Sleep hygiene has been defined as practising behaviours that facilitate sleep and avoiding behaviours that interfere with sleep (Brown, Buboltz, & Soper, Reference Brown, Buboltz and Soper2002; Mindell, Meltzer, Carskadon, & Chervin, Reference Mindell, Meltzer, Carskadon and Chervin2009). They are simple behaviours that can be undertaken at little to no extra cost by simple lifestyle modifications. Most are thought to influence good functioning and performance by ensuring better quality restorative sleep.

Sleep hygiene has recently been made quantifiable by the development of valid scales such as the Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI; Mastin, Bryson, & Corwyn, Reference Mastin, Bryson and Corwyn2006) and has been linked to EDS. The purpose of this study is to examine the dose–response association between sleep hygiene and EDS using available quality measuring instruments like SHI and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS; Johns, Reference Johns1991). There are no studies that have examined sleep hygiene and sleepiness in India.

Regardless of nation, the literature available on quantification of sleep hygiene is scant and, given the importance of good sleep quality and quantity on short- and long-term health of individuals, this should be studied and understood scientifically. Understanding the relationship between sleep hygiene and sleepiness will widen the avenue into the therapy of sleep problems regardless of etiology. Recent literature suggests the role of nonpharmacological therapies is important in treating many sleep problems (Azad, Byszewski, Sarazin, McLean, & Koziarz, Reference Azad, Byszewski, Sarazin, McLean and Koziarz2003; Chesson et al., Reference Chesson, Anderson, Littner, Davila, Hartse, Johnson and Rafecas1999; Harsora & Kessmann, Reference Harsora and Kessmann2009; Hoch et al., Reference Hoch, Reynolds, Buysse, Monk, Nowell, Begley and Dew2001; Siriwardena et al., Reference Siriwardena, Apekey, Tilling, Harrison, Dyas, Middleton and Qureshi2009; Stepanski & Wyatt, Reference Stepanski and Wyatt2003; Weiss, Wasdell, Bomben, Rea, & Freeman, Reference Weiss, Wasdell, Bomben, Rea and Freeman2006; Wildschiodtz & Rasmussen, Reference Wildschiodtz and Rasmussen1981). Further, clarifying the sleep hygiene–sleepiness relationship should be particularly useful in population groups where hours are long and/or unpredictable, such as resident doctors, shift work employees, IT and BPO professionals.

Method

Participants

Data were solicited from 430 volunteering junior resident doctors (M = 26.6 years, SD = 2.2 years; 80.6% male, 16.4% female) from an urban teaching hospital in India over the course of 12 months. The sociodemographic factors (refer to Table 1) showed 80.6% of the participants were male and 19.4% were female. The age range of the respondents was from 21 to 37 years. Among the study participants 26.3% were married and 73.3% were unmarried. Of the 430 resident doctors contacted, 2 were excluded and 350 responded. The response rate was 81.77%. The study was approved by a university institutional review board and all participants provided written consent prior to being enrolled in the study.

TABLE 1 Socio Demographic and Lifestyle Profile of Study Participants

Prevalence of Sleepiness and Poor Sleep Hygiene

Of the 350 participants studied in the survey, 303 (86.6%) belonged to clinical departments and 47 (13.4%) to nonclinical departments. The clinical participants primarily came from the departments of anaesthesia (10.6%), medicine (16.9%), surgery (24%), and paediatrics (15.7%). The nonclinical participants primarily came from the departments of biochemistry (0.9%), microbiology (2.9%), pathology (1.4%), pharmacology (2.9%), community medicine (2.6%) and radio-diagnosis (2.6%).

Measures

Sleep assessment proforma

Information was collected on sociodemographics and sleep-related factors for descriptive purposes (Sandia National Laboratories & Sandia Corporation, 2007).

Epworth sleepiness scale

The ESS is an 8-item self-administered questionnaire producing scores that range from 0 (low sleepiness) to 24 (high sleepiness) with scores exceeding 10 indicating abnormal levels of sleepiness (Johns, Reference Johns1991). The ESS has demonstrated good validity in correlating with objective measures of sleepiness and an ability to discriminate between control subjects and those with significant sleep disorders (Johns, Reference Johns1991, Reference Johns1992; Miletin & Hanly, Reference Miletin and Hanly2003). Scores were evaluated as 0–9 normal, 10–12 mild EDS, 13–14 moderate EDS, >14 severe EDS (Zielinski et al., Reference Zielinski, Polakowska, Kurjata, Kupsc and Zgierska1998).

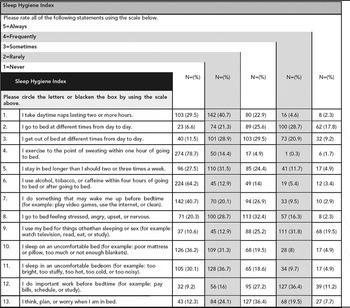

Sleep hygiene index

The SHI is a 13-item self-administered Likert scale index that assesses behavioural patterns associated with sleep hygiene practices. Responses to each item are based on the frequency with which the person engages in the behaviour from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Items are summed to provide a global assessment of sleep hygiene with scores ranging from 13–65. Higher global scores are indicative of more maladaptive sleep hygiene practices (Mastin et al., Reference Mastin, Bryson and Corwyn2006). For the purposes of this study, a score below 26 was considered good, 27–34 as average, and 35 and above was considered as poor sleep hygiene (Mastin et al., Reference Mastin, Bryson and Corwyn2006). The internal consistency for the SHI is moderate (α = 0.66), and expected for an instrument with independent causal indicators. Mastin and colleagues (Reference Mastin, Bryson and Corwyn2006) demonstrated good test–retest reliability for the SHI (r = 0.71). The SHI has been correlated with the PSQI and ESS (Mastin et al., Reference Mastin, Bryson and Corwyn2006).

Procedure

All participants completed a package that included a demographics form, SHI, ESS, sleep assessment questionnaire and informed consent. Participants were able to complete the package in less than 50 minutes. All data was stored in a secure location and subjects were assured all responses would remain confidential. Subjects were met in their respective department or place of work and, for those volunteering, appointments were made for data collection. Informed consent and sociodemographic data were collected followed by self-administration of the instruments in sequence of the sleep assessment proforma, ESS and SHI. The data collection was conducted mainly in the afternoons, postlunch sessions and early evening. A significant number of subjects (about 70%) were allowed to return the forms after completing them in their free time. Subjects who were pregnant, sick or admitted as patients to the hospital were excluded from the study.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Included in Table 1 are participant characteristics that might be associated with poor health or sleep disruption. For example, the consumption of more than two cups of tea/coffee was reported by 34.3% of the study participants and 42.3% of the study participants consumed coffee or tea within four hours of bedtime. Smoking tobacco was reported by 8% of the study participants. Body mass index (BMI) was found to be normal in 66.9%, obesity range in 24.9% and lower range in 5.1% of the study participants. Some behaviours of interest, and potentially associated with health and sleep outcomes are reported, but beyond the scope of this article. For example, physical activity other than work was reported by 39.3% of participants.

Prevalence of Sleepiness and Poor Sleep Hygiene

As seen in Table 2, excessive sleepiness, as detected by the ESS was found in 47.4% of our participants (26% were classified as mildly sleepy, 9.4% as moderate, and 12% as seriously sleepy). Maladaptive sleep hygiene, as measured by the SHI, was prevalent among 85.7% of residents.

TABLE 2 Total ESS and SHI Scores

Prevalence of Poor Sleep Quality

Prevalence of Poor Sleep Quality

Table 3 shows the self-rating by the respondents to the question ‘What is the quality of your sleep?’ with eight options ranging from extremely good to extremely poor. Results were 45.6% responded extremely good to good, 43.8% fair or adequate, 10.5% responded poor to extremely poor. In those with EDS, 36.7% rated quality as extremely good to good and 48.2% rated as fair or adequate and 15.1% responded poor to extremely poor.

TABLE 3 Self Rated Sleep Quality on 1-8 Ordinal Scale by the Study Participants*

Prevalence of Subjective Sleepiness and Tiredness

Prevalence of Subjective Sleepiness and Tiredness

Participants were asked to indicate on a 0–10 scale both how sleepy and how tired they were on the test day, with lower scores indicating less of these states. The mean score for self-rated responses to sleepiness was 4.41 (SD = 2.33) and tiredness 4.73 (SD = 2.62).

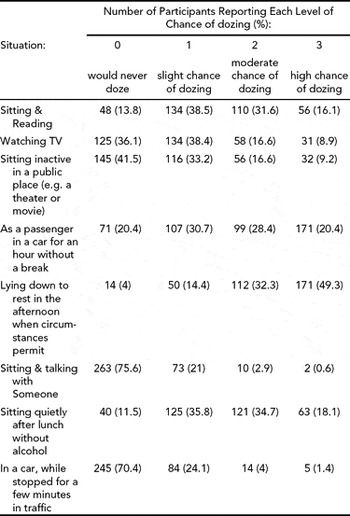

Table 4 shows the responses to Epworth Sleepiness Scale items, where the proportion of responses to moderate- to high chance of dozing was higher with items, ‘Sitting & Reading’, Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit’, and ‘Sitting quietly after lunch without alcohol’.

TABLE 4 Item Wise Responses to Epworth Sleepiness Scale by Study Participants

Relationship of EDS to Poor Sleep Hygiene

Relationship of EDS to Poor Sleep Hygiene

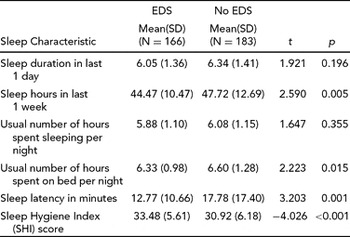

Table 5 shows comparisons of mean SHI scores in No EDS and EDS groups. The mean score for 183 respondents with No EDS was 30.92 (SD = 6.18) and for 166 respondents with EDS 33.48 (SD = 5.61). The difference in means was statistically significant.

TABLE 5 Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI) Mean Scores in Participants With and Without EDS

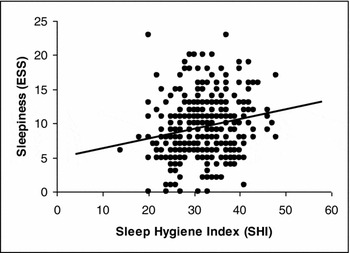

Figure 1 shows the small but significant positive relationship between sleepiness and sleep hygiene (r(348) = 0.186; p < .001).

FIGURE 1 Linear regression curve of SHI scores with original ESS scores.

Table 6 shows the odds ratio for association between sleep hygiene and excessive daytime sleepiness. The Mantel–Haenszel (Nichols, Reference Nichols1994) common odds ratio was estimated to be 2.98, with Breslow-Day and Tarone tests of homogeneity of odds ratio and Mantel–Haenszel test for conditional independence being significant (p < 0.001). The Mantel–Haenszel chi-square is 10.85 with a p value of .000988. The role of chance for odds ratio was ruled out with p < .001. The 95% confidence interval ranged from lower bound limit 1.54 and upper bound limit 5.83.

TABLE 6 Association of Sleep Hygiene with EDS

Table 7 shows that actual ratings of SHI items by resident doctors as having performed these behaviours always to never on an ordered scale. Items 2, 3, 9, 12, and 13 have been reported as frequently to always by relatively more number of resident doctors.

TABLE 7 Item Wise ratings of SHI by Study Participants

Table 8 shows the mean differences and statistical difference in the means between EDS and No EDS groups. The EDS group was significantly more likely than the No EDS group to have variable bedtimes (t(346) = −3.38; p < .05), to have variable wake times (t(347) = −2.63; p < .05), to stay in bed longer than they should two to three times per week (t(347) = −2.16; p < .05), to go to bed feeling stressed, angry, upset or nervous; to use their bed for things other than sleeping or sex (t(347) = −3.85; p < .05); and to think, plan, or worry in bed to have variable bedtimes (t(347) = −1.83; p < .05).

TABLE 8 Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI) Item Means in Study Subjects With and Without EDS

Relationship of EDS to Sleep Duration and Work Time

Relationship of EDS to Sleep Duration and Work Time

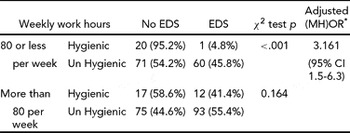

Prevalence odds ratios show that there is a 1.7 times greater chance of developing EDS when working >80 hours (Table 9), suggesting that limiting work hours to 80 hour per week is associated with lower levels of EDS.

TABLE 9 Association of Duration of Weekly Work Hours With EDS

Table 10 shows the self-reported mean hours of sleep duration in the recent past in resident doctors with and without EDS on Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). Compared to the EDS group, the No EDS group obtained significantly more sleep in an average week, spent significantly more time in bed on an average night and took significantly less time to fall asleep.

TABLE 10 Comparison of Means of Self Reported Sleep Characteristics Between EDS and No EDS Groups

These participants showed a significant relationship between weekly work hours, sleep hygiene and EDS. Table 11 shows that, for participants working 80 hours per week or less, good sleep hygiene is associated with low probability of EDS; but that even with low work hours poor sleep hygiene showed a significant increase in EDS. For participants working more than 80 hours per week, sleep hygiene was not statistically associated with EDS.

TABLE 11 Stratified Analysis for Association Between EDS and Weekly Work Hours

* MH-Mantel-Haenszel Odds Ratio

Discussion

The sociodemographic profile of the resident physicians (see Table 1) revealed no differences in the prevalence of EDS due to sex, marital status, coffee intake or tobacco use. The present study revealed that 47.4% of the resident physicians studied were excessively sleepy (see Table 2). There have been no previous studies to assess country-level or specific work group prevalence of EDS in India. The results are comparable with the previous studies conducted with resident physicians in US and Europe (Handel, Raja, & Lindsell, Reference Handel, Raja and Lindsell2006; Papp et al., Reference Papp, Stoller, Sage, Aikens, Owens, Avidan and Strohl2004; Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Bellini and Shea2004). A similar high prevalence of EDS had also been recorded in and outside of the US in other professions that are similar in respect to long work hours (Gallup Organization, 2003; Joo et al., Reference Joo, Shin, Kim, Yi, Ahn, Park and Lee2005; Mello et al., Reference Mello, Santana, Souza, Oliveira, Ventura, Stampi and Tufik2000; Tsuno et al., Reference Tsuno, Jaussent, Dauvilliers, Touchon, Ritchie and Besset2007).

A little more than half of the physicians rated their sleep quality as fair to extremely poor (see Table 3). Of those doctors with EDS, nearly two thirds reported fair to extremely poor sleep quality. It is generally accepted that poor sleep quality is an important precursor of EDS (Hasler et al., Reference Hasler, Buysse, Gamma, Adjacic, Eich, Rossler and Angst2005; LeBourgeois, Avis, Mixon, Olmi, & Harsh, Reference LeBourgeois, Avis, Mixon, Olmi and Harsh2004; Vignatelli et al., Reference Vignatelli, Bisulli, Naldi, Ferioli, Pittau, Provini, Plazzi, Vetrugno, Montagna and Tinuper2006). It appears that the residents with EDS had some awareness of their own sleep difficulties. However, scores from a visual analogue scale self-rating 0–10 for ‘How sleepy are you today?’ and ‘How tired are you today?’, although statistically higher for the EDS group, were not generally high for either group. It may be that the studied physicians had some awareness of sleep quality problems, but either were unwilling to admit or were unaware of the presence of their own excessive daytime sleepiness.

An examination of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores, where respondents were asked to self-report their own chances of falling asleep under various environmental conditions (see Table 4), revealed that almost 25% of the studied physicians reported a slight or greater chance of falling asleep while sitting and talking to someone and over 25% admitted they had a slight or greater chance of falling asleep while stopped in traffic. In summary, it appears that although many subjects described poor sleep quality and the potential to fall asleep, most rated their current levels of tiredness and sleepiness as moderate. If these physicians are unable and/or unwilling to identify current levels of tiredness or sleepiness, it becomes more important to understand why these states exist and what interventions could be suggested.

The mean sleep hygiene scores were higher (i.e., more maladaptive) for the sleepy physicians (see Table 5) and a positive correlation was found between sleepiness and sleep hygiene (see Figure 1). The prevalence of EDS in the group with more maladaptive sleep hygiene was 48.8%, whereas the prevalence of EDS in the more adaptive sleep hygiene group was 26%. Another means of communicating this relationship is that physicians with more maladaptive sleep behaviours as indicated by SHI had a three times higher chance of experiencing EDS (see Table 6). As the Sleep Hygiene Index is constructed by a set of potentially independent items, it is as important to consider the items individually.

Five SHI items (see Table 7) were identified (2, 3, 9, 12 and 13) as having been engaged in as frequently to always by relatively more physicians. Of the overall total SHI scores, 44.32% was contributed by the frequently to always categories of these items. Items two and three (‘I go to bed and get out of bed at different times’) pertain to maintaining a regular time for going to and rising from bed. We suggest these maladaptive behaviours are likely a result of unstable work schedules. Item nine and thirteen (‘I use my bed for things other than sleeping or sex’ and ‘I think, plan, or worry when I am in bed’) are likely related to limited space available in hostel rooms where many of these residents reside. Most medical residents in India are assigned a single ten by ten foot room with a study table, a chair and a cot. This may have led the subjects to use their bed for nonsleep purposes such as work, study or other activating behaviours. Finally, item 12 (‘I do important work before bedtime’) may reflect their effort to manage time when working extended work schedules.

Six SHI items (see Table 8) were identified (2, 3, 5, 8, 9 and 13) as having been engaged in more frequently by physicians with EDS. Of the overall total SHI scores, 53.6% was contributed by these items. Items 2 and 3 (‘I go to bed and get out of bed at different times’) and item 9 (‘I use my bed for things other than sleeping or sex’) were again identified as problematic. Additionally, item 5 (‘I stay in bed longer than I should two or three times a week’) is likely a result of attempted extended recovery sleep. Items 8 (‘I go to bed feeling stressed, angry, upset, or nervous’) and 13 (‘I think, plan, or worry when I am in bed’) suggest emotional disruption in combination with a sleep debt resulting in stimulus discrimination problems.

Among the residents with EDS, 36.7% were working 80 or fewer hours per week and 63.3% were working more than 80 hours per week. The frequencies (see Table 9) were significantly different and suggest a 1.7 times greater risk of EDS for those subjects working more than 80 hours per week. An association between higher work hours in a week and EDS has been demonstrated in several studies from a number of different countries, including Canada (Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Hayter, Bould, Joo and Naik2009), New Zealand (Gander et al., Reference Gander, Purnell, Garden and Woodward2007), United States (Defoe et al., Reference Defoe, Power, Holzman, Carpentieri and Schulkin2001; Gander et al. Reference Gander, Purnell, Garden and Woodward2007), Australia (Dorrian et al., Reference Dorrian, Lamond, van den Heuvel, Pincombe, Rogers and Dawson2006), Japan (Kaneita et al., Reference Kaneita, Ohida, Uchiyama, Takemura, Kawahara, Yokoyama and Akashiba2005) and others (Groeger, Zijlstra, & Dijk, Reference Groeger, Zijlstra and Dijk2004; Jagsi et al., Reference Jagsi, Weinstein, Shapiro, Kitch, Dorer and Weissman2008; Jewett, Dijk, Kronauer, & Dinges, Reference Jewett, Dijk, Kronauer and Dinges1999; Kaneita et al., Reference Kaneita, Ohida, Uchiyama, Takemura, Kawahara, Yokoyama and Akashiba2005; Klerman & Dijk, Reference Klerman and Dijk2005; Liu, Uchiyama, Kim, et al., Reference Liu, Uchiyama, Kim, Okawa, Shibui, Kudo, Doi, Minowa and Ogihara2000; Ohida et al., Reference Ohida, Osaki, Doi, Tanihata, Minowa, Suzuki and Kaneita2004; Skeff, Ezeji-Okoye, Pompei, & Rockson, Reference Skeff, Ezeji-Okoye, Pompei and Rockson2004; Steinbrook, Reference Steinbrook2002).

The self-reported total hours slept in one week by resident doctors differed significantly between the EDS and No EDS groups (6.05 vs. 6.34; see Table 10). The effect of inadequate sleep on EDS is well documented in resident physicians and the general population, (Dorrian et al., Reference Dorrian, Lamond, van den Heuvel, Pincombe, Rogers and Dawson2006; Groeger et al., Reference Groeger, Zijlstra and Dijk2004; Jewett et al., Reference Jewett, Dijk, Kronauer and Dinges1999; Kaneita et al., Reference Kaneita, Ohida, Uchiyama, Takemura, Kawahara, Yokoyama and Akashiba2005; Klerman & Dijk, Reference Klerman and Dijk2005; Liu, Uchiyama, Kim, et al., Reference Liu, Uchiyama, Kim, Okawa, Shibui, Kudo, Doi, Minowa and Ogihara2000; Liu, Uchiyama, Okawa, et al., Reference Liu, Uchiyama, Okawa and Kurita2000; Ohida et al., Reference Ohida, Osaki, Doi, Tanihata, Minowa, Suzuki and Kaneita2004; Takegami, Sokejima, Yamazaki, Nakayama, & Fukuhara, Reference Takegami, Sokejima, Yamazaki, Nakayama and Fukuhara2005), but this is the first study of its kind available from India (Gupta, Pati, & Levi, Reference Gupta, Pati and Levi1997; Kannan, Malhotra, Bajaj, Pershad, & Chari, Reference Kannan, Malhotra, Bajaj, Pershad and Chari1996). Suggested explanations for an association between sleepiness and work hours includes stress related to work, burnout, inadequate sleep hours, sleep deprivation and sleep debt and other work-related characteristics like floating shift work.

The overall mean work hours per week in our study exceeded the weekly work hour norms established by medical education regulation boards in some countries (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2007; Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education, 2002; Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety, 2008). For example, in 2003 in the US, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education set up legally binding guidelines limiting the work hours to 80 per week and not more than 24 consecutively (Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education). Such regulations also exist in Australia (Gander et al., Reference Gander, Purnell, Garden and Woodward2007), Canada, the United Kingdom (Cappuccio et al., Reference Cappuccio, Bakewell, Taggart, Ward, Ji, Sullivan, Edmunds, Pounder, Landrigan, Lockley and Peile2009) and other European countries. Recent recommendations from the Institute of Medicine in the US have reaffirmed the need for stricter adherence (Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety, 2008). Even though the problem of unregulated long hours and their consequences exist, there are no policy documents available limiting the work hours of trainee doctors or medical professionals in India. At the particular institution studied here (Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research), there were no set guidelines on resident work hours and working conditions.

It appears that for these resident doctors, hours worked interacted with hours slept and a maladaptive sleep lifestyle leading to EDS (see Table 11). In the group working 80 or less hours a week, the prevalence of EDS differed significantly between the adaptive and maladaptive sleep hygiene groups (4.8% vs. 45.8% respectively; see Table 11). Whereas the prevalence of EDS in those with adaptive and maladaptive sleep hygiene for residents working 80 hours per week and more was not significantly different (41.4% vs. 54.4% respectively). It is likely that individuals working more than 80 hours a week are sleepy regardless of sleep hygiene practices.

We suggest that for these residents, sleep hygiene and work hours interact as risk factors to predict EDS. In residents with 80 or less hours of work, sleep hygiene plays an important role in anticipating EDS and when the work hours extend beyond 80 hours, sleep time and sleep hygiene may become curtailed/disrupted to the extent that avoiding sleepiness may be difficult.

Limitations

Of the 430 resident doctors in this study who were solicited to volunteer, 350 responded. The response rate was 81.77%, better than similar studies on with attendees in India (65.3%; Alattar, Harrington, Mitchell, & Sloane, Reference Alattar, Harrington, Mitchell and Sloane2007), in junior doctors in New Zealand (63%; Gander et al., Reference Gander, Purnell, Garden and Woodward2007), and in Canadian anaesthesia residents (77%; Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Hayter, Bould, Joo and Naik2009).

This study was based on self-report. There were chances of biases such as socially desirable responses and the accuracy of reported information. In addition, some of the responses involved reporting of events up to one month prior such that recollection may have been an issue.

Even though the tools were validated in the context of western countries and some Asian nations, good quality studies validating the ESS and SHI from India were not available. Fluency in written English is a requirement for the subjects and was not considered an issue. The relevance of these instrument items in the Indian context for resident doctors is unknown. Some junior residents reported that they did not face some of the situations mentioned in the ESS in the recent past. The effect of responses in such cases on results is unknown.

Conclusion

Almost half of the resident physicians studied reported a problem of EDS and maladaptive sleep hygiene practices. Sleep hygiene and number of hours slept should be considered as EDS prevention and treatment strategies, especially for physicians working less than 80 hours per week. Physicians working more than 80 hours per week were much more likely to report EDS. We suggest the most salient intervention for physicians working more than 80 hours per week is one of workplace advocacy where the government is encouraged to adopt legally binding guidelines as seen in other countries, such as limiting the work hours to 80 per week and not more than 24 hours consecutively.