1. Introduction

Professor Susan J. Pharr pioneered the political study of Japanese women. Her book, Political Women in Japan, was the first on the topic in English. When published in 1981, Japan had very few female politicians at either the national or the local level. Pharr interviewed 100 young politically active women (aged between 18 and 33) to find out why. She discovered that most of her interviewees accepted the prevailing gender norms except for a minority of women she called Radical Egalitarians (about 20% of the interviewees). The vast majority (60% of her interviewees) embraced their future roles as wives and mothers, even if they also considered it acceptable for women to engage in activities beyond the confines of their home. Pharr named this majority group New Women. A further 20% of women who adhered to the most traditional gender expectations, she named Neo-Traditional women.

The aim of this paper is to reconsider Pharr's groundbreaking work in the light of changes over the last few decades. Like Pharr, this paper draws upon interviews and biographical details to assemble a picture of how women in different cohorts view their gender roles and political representation. Today Japan still stands out for its dearth of women in decision making in politics, government agencies, and corporations. The most recent Global Gender Gap Report 2021 ranks Japan at 147th out of 155 countries in the political empowerment of women (World Economic Forum, 2021). When we turn to the private sector, the picture remains the same. The Global Gender Gap Report ranks Japan at 117th out of 156 countries (World Economic Forum, 2021). It is no wonder that when the foreign media writes about Japanese women – whether women in the imperial family or ordinary women – the stories emphasize the traditional and gender-discriminating nature of Japan. In 2018, the Abe Administration passed the Law on the Promotion of Gender Equality in Politics. However, just like the earlier Equal Employment Opportunity Law of 1985, the new law imposed no penalty on political parties that failed to meet the targets. Abe's critics doubt that his government made much progress on reducing gender inequality (Miura, Reference Miura2016; Dalton, Reference Dalton2017; for a more favorable view, see Noble, Reference Noble and Steel2019).

My focus in this paper is on the changes that have occurred in the political representation of women in Tokyo rather than Japan as a whole. Since 1990, the share of women in the Special Ward assemblies in Tokyo has risen threefold from roughly 10 to 30%. In the last general local elections in 2019, the top vote getters were female candidates in 15 of Tokyo's 23 Special Wards (Tokubetsu-ku). Furthermore, in the latest election for Tokyo's Metropolitan Assembly (the prefectural level assembly) in 2021, the share of female assembly members rose to 32%. The Metropolitan Assembly members are elected from 41 districts and female candidates were the top vote getters in 16 of them. The Governor of Tokyo is also a woman, Yuriko Koike. Given Japan's persisting gender inequality, the rise in the share of women at local assemblies in Tokyo is impressive.Footnote 1 Japan is a highly centralized country and Tokyo, as the political, social, and economic center, attracts young people from the rest of the country. This makes Tokyo the best place to understand the scope of socio-economic changes affecting women in Japan. This article asks the following inter-related questions. What parties fielded the largest number of female candidates? Who were these female candidates? Have there been any shifts in the composition of female candidates and, if so, why? To what extent, have political women in Japan changed since Pharr's Political Women in Japan?

2. Female political representation in Tokyo in a national perspective

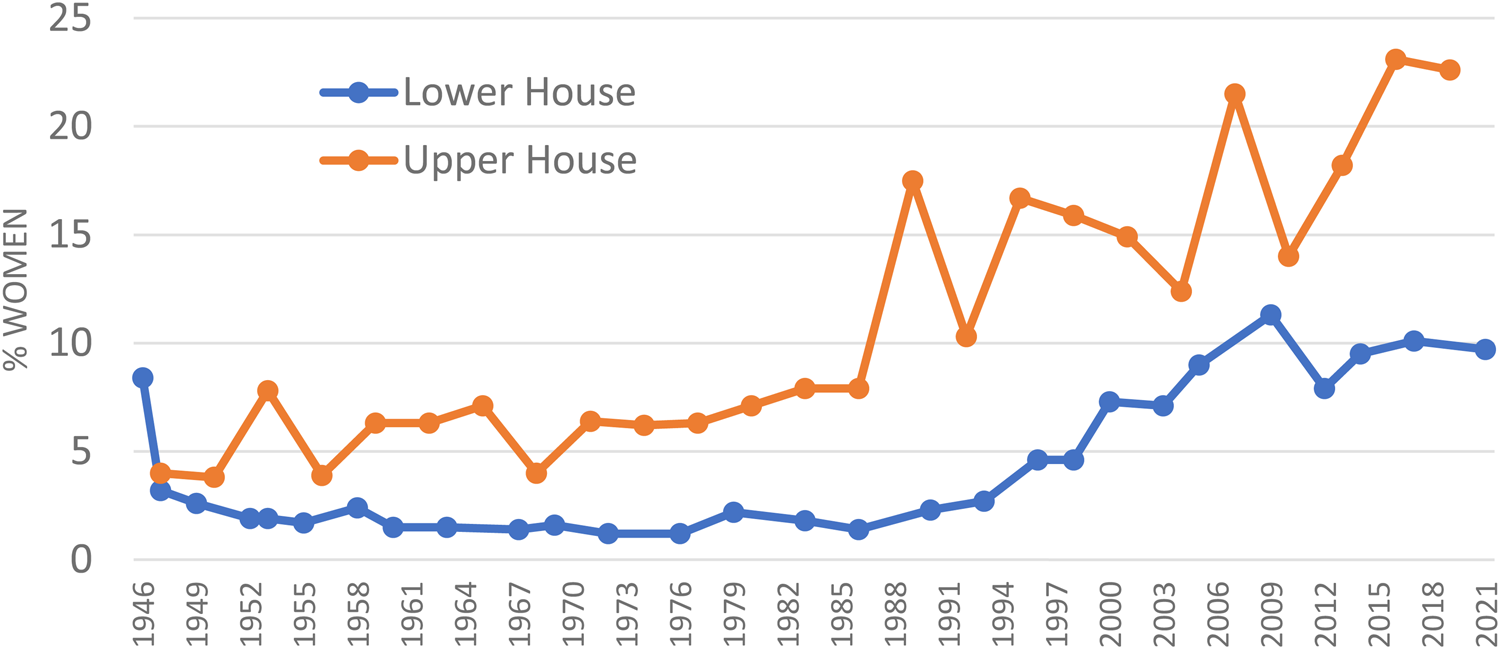

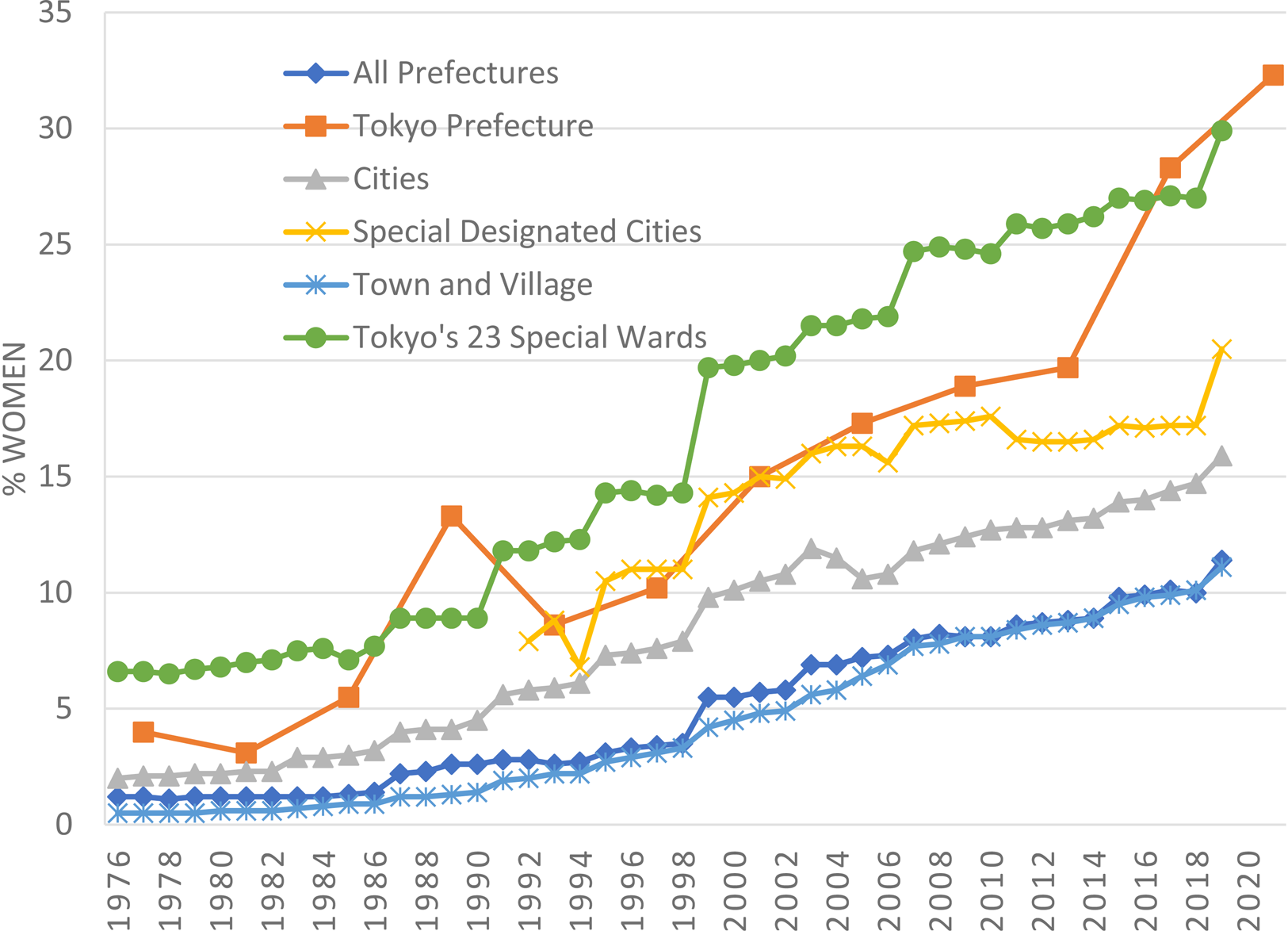

Pharr noted in 1981 that the pattern of female political representation in Japan was the opposite of the USA as the share of women in local assemblies was smaller than the share of women in the Diet. At the aggregate level, this is still true. Figures 1 and 2 show the shares of women in the Diet (Shugiin and Sangiin) and in different local assemblies, respectively. When we compare Figure 1 to the blue diamond-dotted line in Figure 2, we can see that the national average share of women in all local assemblies is lower than the share in the Diet. However, when we go beyond the national average and look at the share of women in different types of local assemblies, a very different picture emerges. Figure 2 shows that the share of women increased much more rapidly in some local assemblies than in others: the more urban the municipality is, the greater the share of female assembly women. The average share of women in city assemblies is several points higher than that in village and town assemblies and even higher in more densely populated large cities (called Seirei Shitei Toshi, Special Designated Cities) relative to smaller cities. Furthermore, the share of women in local assemblies in the 23 Special Wards (Tokubetsu-ku) – the most urban areas of Tokyo – is three times greater than for village and town assemblies. The share of women in the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly is also three times higher than the average for all prefectural assemblies nation-wide.

Figure 1. Share of women in the lower (Shugiin) and upper house (Sangiin).

Source: Figures for the Shugiin, the Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office, https://www.gender.go.jp/about_danjo/whitepaper/r03/zentai/html/honpen/csv/zuhyo01-01-01.csv, figure for the Sanngiin, the Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office, https://www.gender.go.jp/about_danjo/whitepaper/r03/zentai/html/honpen/csv/zuhyo01-01-02.csv, and the figure for the 2021 Shugiin election is from https://www.soumu.go.jp/senkyo/senkyo_s/data/shugiin49/index.html.

Figure 2. Share of women in local assemblies by type of administrative unit in %.

Source: The figures for the Tokyo Prefectural Assembly are from the Bureau of Citizens and Cultural Affairs, Tokyo Metropolitan Government, https://www.seikatubunka.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/danjo/houkoku/data/files/0000001316/2019-2-5-3.csv. The rest of the figures are from the Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office, https://www.gender.go.jp/about_danjo/whitepaper/r02/zentai/html/zuhyo/zuhyo01-01-06.html.

The historical shifts in the share of women in local assemblies shown in Figure 2 differ distinctively from the pattern shown in Figure 1 for the two chambers of the Diet. The lines dotted with circles (Special Ward assemblies) and squares (Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly) in Figure 2 stand in stark contrast to the line for the Upper House (Sangiin) in Figure 1. It is striking how the line of the Sangiin zigs and zags while the line for Tokyo's Special Ward assemblies shows a steady and uniform upward trend. However, we can observe a spike in the line for the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly in 1989 – a similar spike is evident for the Sangiin in the same year, but the Sangiin continues to experience ups and downs in ways that the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly does not. Note that, as Figure 1 shows, the share of women in the Upper House (Sangiin) is twice as high as in the Lower House (Shugiin). This is just the opposite of the USA, where more women are elected to the Lower House (the House of Representatives) than to the Upper House (the Senate).

Why does the level of female political representation vary so widely from one assembly type to another? Political scientists usually consider the following three factors as the main culprits: (i) district magnitude; (ii) the relative strength of the opposition parties; and (iii) the electoral strategies of political parties. Martin (Reference Martin and Steel2019) shows that large district magnitudes are more favorable to women in Japan. In fact, Tokyo's 23 Special Wards have district magnitudes significantly larger than less urban municipalities. A larger district magnitude translates to a lower electoral threshold and a greater proportional outcome, which makes it easier for opposition party candidates and independent candidates to be elected. This logic can be applied to the gender gap between the Sangiin and the Shugiin. The Sangiin has always had a larger median district than the Shugiin, making it easier for the opposition parties to win seats. If the opposition parties are more likely to field female candidates, a large district magnitude will result in the election of more women.

As is the case in other countries, the relative electoral strength of left-leaning opposition parties has also affected political representation of women in Japan. The Japan Socialist Party (JSP) and the Japan Communist Party (JCP) have always fielded more female candidates than the conservative ruling party, Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). There have been more female local politicians in Tokyo's municipal assemblies because the JSP, the JCP, and independents have historically won more seats in urban municipalities – particularly in Greater Tokyo – as evidenced by the rise of Kakushin Jichitai from the late 1960s into the 1970s (Scheiner, Reference Scheiner2006). Of the opposition parties, the JCP has been by far the most gender egalitarian (Oki, Reference Oki2008, Reference Oki2019). In fact, when the JCP introduced internal de facto gender parity in fielding candidates, it led to an increase in the female share of local assembly women in Tokyo's Special Districts (Oki, Reference Oki2008). At the local level, the Komeito – a pro-welfare party but not-socialist – has been only second to the JCP in the number of female candidates that it fields (Oki, Reference Oki2008; Martin, Reference Martin and Steel2019). The JCP and the Komeito both have very solid organizational foundations in urban districts and can hence more easily recruit female candidates from within and mobilize their members to vote for these women.

There is a strong synergy between the district size and the relative strength of the opposition. The median district size or the local assembly elections in Tokyo's 23 Special Wards is 28 exceeding the district size in other local assemblies. This large district magnitude has made it easier for smaller parties such as the JCP, the Komeito as well as independent candidates to win seats, which translated into more women being elected. By the same token, a wave of mergers of cities and towns that took place in 2007 – the so-called Heisei Daigappei – favored female candidates by increasing the district magnitude in many local assemblies (Iwamoto, Reference Iwamoto2011; Martin, Reference Martin and Steel2019). Iwamoto (Reference Iwamoto2011) reports that while the Heisei Daigappei reduced the overall number of local politicians from 60,200 in 2003 to 39,789 in 2007, the share of women increased between 2003 and 2007.

Electoral strategies of political parties also matter greatly. The so-called Madonna Boom in 1989 most vividly illustrates this point. The LDP's Takeshita Administration introduced a new consumption tax in 1989 just before the two important elections – the Sangiin and the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly – were scheduled to take place. Takako Doi, the leader of the JSP – the first women to lead any major political party – spearheaded a successful campaign mobilizing housewives' discontent against the new consumption tax and LDP's political scandals. Her strategy to nominate female candidates casting them as morally superior to male incumbents led LDP to lose its absolute majority in the Sangiin. The JSP's electoral success in the 1989 Sangiin election led to a dramatic increase in the number of female Sangiin politicians (see Figure 1). The opposition parties rode on this political tide in the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly election to win more seats and their gains dramatically increased the female share (see the line dotted with squares in Figure 2). The Japanese media coined the term Madonna Boom to refer to these twin big spikes in female political representation in the Sangiin and the Metropolitan Assembly. Many observers were initially astonished that Japanese voters would perceive female candidates so favorably despite the prevailing traditional gender norms in Japan. Nonetheless, more recent studies confirm that Japanese voters indeed hold favorable views of female candidates (Kage et al., Reference Kage, Rosenbluth and Tanaka2019; Eto, Reference Eto2020).

The lesson of the Madonna Boom was not lost on other opposition parties. They saw the electoral merit of fielding female candidates. Female candidates were perceived as ‘less corrupt’ and ‘more in touch’ with the needs of ordinary families. The JSP, JCP, and the Komeito were not the only parties that learned the lesson. The Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), which emerged as a major opposition party in the 2000s, fielded significantly more female candidates in local elections than the LDP (Gaunder, Reference Gaunder2012). Most recently, in 2016, the former LDP Diet member, Yuriko Koike, cleverly took advantage of the benign image of female politicians to become the Governor of Tokyo accusing her predecessor, Yoichi Masuzoe – an LDP colleague – for his unethical use of public funds and successfully defeating the candidate nominated by the LDP to replace Masuzoe. She also criticized the LDP-dominated Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly and founded a new local political party called Tomin Fasuto (Tokyo Residents First) to contest the assembly election in 2017. Prior to the founding of the Tomin Fasuto, Koike organized a series of workshops for people interested in running for office and recruited some female participants to run as Tomin Fasuto candidates in the upcoming election. Tomin Fasuto's electoral success contributed to the big jump in the number of women elected to the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly in 2017 (as evidenced in Figure 2). Koike also maneuvered a merger of the DPJ into her new national political party, Kibo no To (the Hope Party), and caused the DPJ to be disbanded and split into smaller parties in 2017. These developments, as we shall see, affected the local elections that took place in 2019.

As already noted, the share of women in the Tokyo's Special Ward assemblies grew steadily in a more or less linear manner from the early 1990s onward (see Figure 2). Nonetheless, we can observe three distinctive stages in the historical rise of female political representation in Special Wards: the first stage begins in 1991; the second stage begins in 1999; and the third stage begins in 2007. There is again a big increase in 2019, which may signal the beginning of the fourth stage. In order to understand how the female political representation increased in Tokyo's Special Districts, we have to move beyond the three factors discussed so far (i.e., the district size, the electoral strategies, and performance of the opposition parties) and also pay close attention to the socio-economic transformations, which changed women's lives. These transformations reshaped the supply of female candidates as well as the demand for policies in Tokyo. Once the electoral competition intensified in Tokyo, more parties began to recruit new different types of female candidates in their attempt to attract specific types of female voters.

The following sections discuss: (i) the specific socio-economic developments that affected women's choices and their political representation; and (ii) new types of female politicians that emerged in Tokyo as a result.

3. Rise of housewives' political movement Seikatsusha Nettowaku in the 1990s

Until the 1991 general local elections, well over half of local assembly women in Japan had been Communist and Socialist women. During the 1980s, the JCP alone elected more than 40% of local assembly women, the Komeito trailed behind the JSP – and far behind the JCP (Ichiikawa Fusae Kinenkai, Reference Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai2018: 39). Profound changes came about during the 1990s. The partisan composition of female assembly women changed, and so did the types of women who became politicians. While communist and socialist women used to dominate the scene, the Komeito began to field a lot more women consequently becoming the second largest political party in terms of the number of local assembly women. The Komeito nearly doubled the number of women it elected to local assemblies in Japan. Furthermore, in the wealthy suburbs of Tokyo – located both in Tokyo and Kanagawa prefectures – a movement-based group called the Seikatsusha Nettowaku (Netto) surged to become the third largest group of female assembly women after the JCP and the Komeito (ibid.).

The Netto – along with the Komeito – contributed a lot to the rise in female political representation in the 23 Special Wards and outer suburbs in Greater Tokyo. The Netto is a political offshoot of a cooperative movement called the Seikatsusha Club whose members mainly consist of suburban housewives in affluent residential areas in Tokyo and Kanagawa prefectures. The Netto was a political movement of housewives who felt that ordinary citizens should have a say in local policies and began fielding their own members to run for prefecture-, city-, and Special Ward-level assembly elections in the late 1980s (Gelb and Estévez-Abe, Reference Gelb and Estévez-Abe1998; LeBlanc, Reference LeBlanc1999). By 1995, the Netto was second only to the JCP in the number of female politicians in city- and ward-level assemblies (Gelb and Estévez-Abe, Reference Gelb and Estévez-Abe1998). In 1999, the Netto assembly women in Tokyo totaled 57 – second only to the JCP (112 women) and the Komeito (69 women) – in contrast to the LDP and the DPJ which trailed far behind with 17 and 18 women, respectively (Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai, Reference Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai1999). Why did this change happen in the 1990s? Were the new assembly women different from the JCP and the JSP assembly women? The following passages answer these questions by closely looking at the case of the Netto women.

Back in the 1970s, when Pharr interviewed young political women in Japan, most of them had tertiary or post-secondary education. Yet 80% of them – 20% Neo-Traditional women and 60% New Women – envisioned their future life as housewives and stay-home mothers. Pharr's interviewees would have been the cohort born between the 1940s and the mid-1950s. This cohort of women entered adulthood well before the legislation of the Equal Employment Opportunity Law (EEOL) in 1985, which legally obligated employers not to discriminate against female job applicants. Until 1985, Japanese large corporations did not hire university-educated women because they expected women to quit upon marriage in their mid-20s. Instead they preferred younger women with high school or junior college degrees (Brinton, Reference Brinton1993). The EEOL came too late for the birth cohorts of the 1940s and 1950s. Barred from the most desirable jobs in corporate Japan, they would marry men with such jobs and become housewives and stay-home mothers. These women, even when they were interested in politics, became housewives unlike their Radical Egalitarian peers who rejected traditional gender roles.

However, by the 1990s – the period immediately after the Madonna Boom in 1989 – the cohort of women born in the late 1940s and the 1950s found themselves in a different stage of their life course. These women had already raised their children and had more time for themselves. The first generation of the Seikatsu Club women who began organizing for the Netto movement belonged to this cohort. Women in the Seikatsu Club and the Netto allow us to see what had become of Pharr's New Women. We had an opportunity to interview Netto members in 1997 when Netto was becoming a big force in local assemblies in the Tokyo/Kanagawa suburbs. Our interviewees mirrored the New Women that Pharr had depicted in her book: they belonged to the same age cohort and with the same acceptance of gender norms (Gelb and Estévez-Abe, Reference Gelb and Estévez-Abe1998). They were well-educated women born in the late 1940s and the 1950s and shared a similar profile. They had all worked before marriage but quit upon marriage. To these women, marriage meant motherhood. They all accepted the gender roles assigned to them by their husbands, parents and the society.

Wealthier suburbs of Greater Tokyo were the Mecca for educated housewives married to employees of Japan's best companies. All this explains why Tokyo – when compared to other prefectures – had a lower employment rate among women in their child-rearing years despite having a bigger share of highly educated women (Iwamoto, Reference Iwamoto2011). No big surprise then that the Netto women emerged and thrived in the Mecca of educated housewives. Netto as a movement was not interested in work–family reconciliation issues even in the late 1990s although they were deeply concerned with eldercare (of their aging parents and in-laws) (Estévez-Abe Reference Estévez-Abe, Schwartz and Pharr2003). Nonetheless, they were not the Neo-Traditionalists of Pharr's book. They were more modern women who engaged in policy-oriented volunteer activities but as mothers and housewives. In this sense, they were Pharr's New Women.

The biography of Masako Ogawara, the most prominent Netto woman, helps illustrate how the Netto women embodied the profile of Pharr's New Women. Ogawara (born in 1953) worked for a small film company after graduating from the International Christian University (a highly regarded 4-year university). Recall that Ogawara's generation of university-educated women were not welcomed in large corporations. Upon marriage in 1979, she quit her job and followed her husband – first moving to Chiba prefecture and then to Setagawa ward always following her husband's job postings. She joined the Seikatsu Club and volunteered in activities related to food safety and environment. In 1993, when she was 40 years old – and having finished with the raising of three children – she successfully ran for a seat in the Tokyo prefectural assembly representing the Netto. Because the Netto believes members and representatives are all equals, no one was supposed to monopolize the same seat. Ogawara hence ‘graduated’ from the Tokyo prefectural assembly in 2005 and successfully ran for a seat in the Upper House in 2007 as a candidate for the DPJ. In 2017, she was elected to the Lower House and reelected again in 2021. Ogawara is the only Netto woman to reach the Diet. Her story hence also tells us a lot about the DPJ's candidate recruitment strategy. The DPJ had no real local organizational network other than the old union-based networks, which it inherited from the predecessors such as the union-backed Democratic Socialist Party and sought cooperation with successful grassroots civic groups in their attempt to recruit high-quality candidates. When Ogawara became the highest ranking ‘housewife politician’ in Japan, not only were there very few female Diet members of her cohort, but those few women in the Diet had very different profiles. The typical profile of female Diet members was either female celebrities recruited by the LDP as vote getters or lawyers, such as the former Socialist party leader, Takako Doi. Someone like Takako Doi, who never married, would fall into Pharr's category of Radical Egalitarians.

Ogawara can be described as Pharr's civic-minded New Woman, who entered politics after her children had grown up. A brief comparison with female local politicians representing the JCP and the Komeito would be useful here. The JCP candidates are professional women – typically nurses and teachers from public sector unions – committed to the ideological positions of their party. In this sense, they belong to Pharr's category of Radical Egalitarians. The Komeito candidates are all members of the religious group Soka Gakkai and are recruited from their women's sections. While it is difficult to fit religiously motivated women into Pharr's three categories of political women, the Komeito women resemble in many ways Neo-Traditionalists.

4. Changing face of women in Tokyo: from housewives to working women and working mothers

The Netto women we interviewed in 1997 were already concerned that the decline in marriage rates and the increase in female employment rates might stall recruitment of new members (i.e., highly educated housewives). Their worries were to become a reality within a decade: the Netto's electoral fortune began to decline in 2007. The number of the Netto representatives reached its peak in 2003 when it boasted 63 representatives – including six of them in the Tokyo Prefectural Assembly (Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai, Reference Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai2003). The Netto representatives stood to be the third largest group of assembly women in Tokyo after the JCP (104 women) and the Komeito (85 women) compared to 16 and 24 women for the LDP and the DPJ, respectively (Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai, Reference Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai2003). In 2007, the Netto with its 55 representatives in urban districts in Tokyo still ranked as the third largest group ahead of the DPJ, a close fourth with 50 women elected. By 2019 the Netto had fallen behind the LDP and the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ; Rikken Minshuto) – the main successor to the DPJ after it split up (Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai, Reference Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai2019).

The electoral demise of the Netto did not result in the drop in the overall number of women in Special Ward assemblies. On the contrary, the share of women continued to rise. Two factors explain these trends. First, socio-economic changes dramatically reduced the share of suburban housewives among younger cohorts – negatively affecting the organizational basis of the Netto. Second, the emergence of the DPJ as a major national opposition party (and later, the emergence of the Tomin Fasuto as a local party) changed the landscape of local elections in urban areas creating opportunities for new types of women to run for office. These two factors together also diversified the types of women who ran for office.

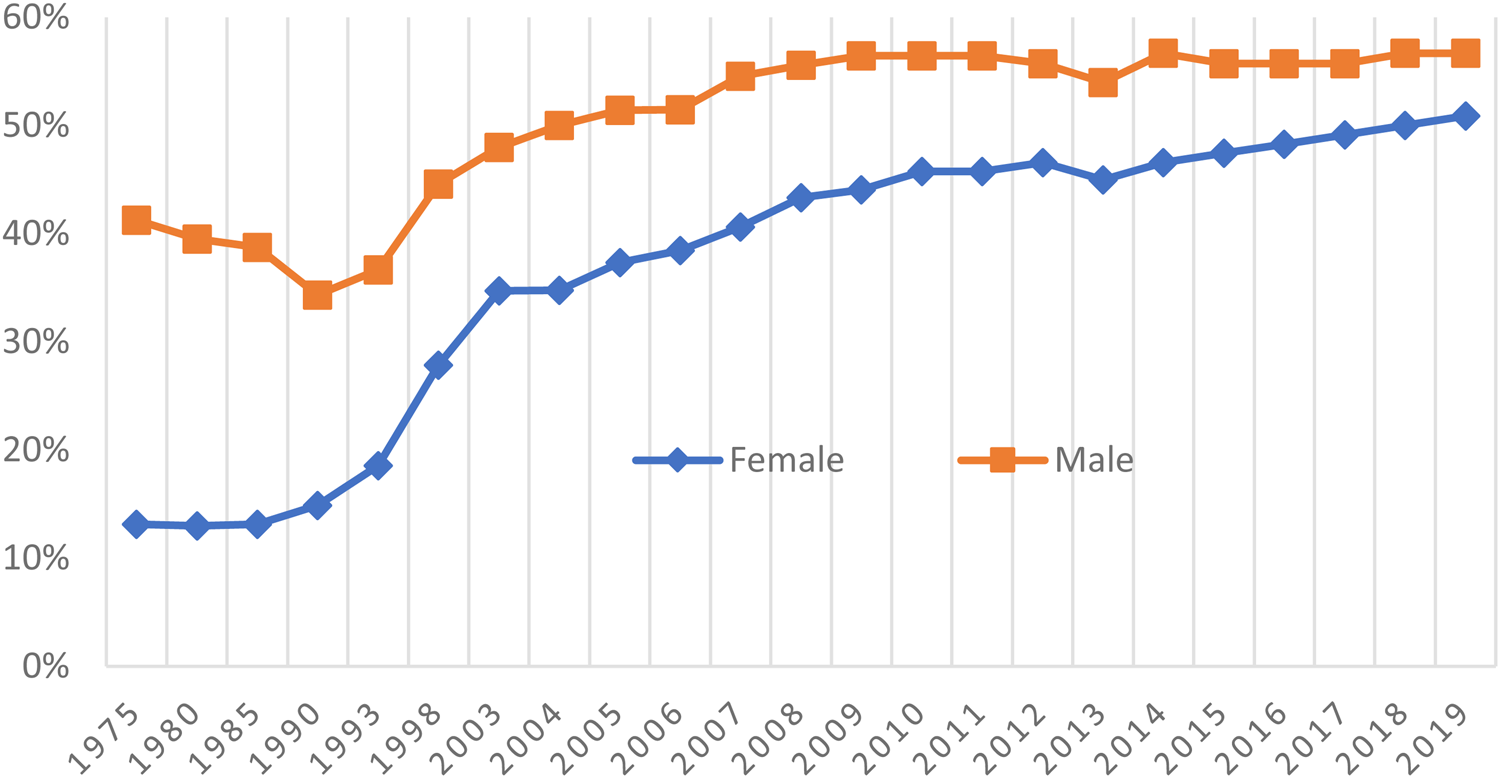

Let me first discuss the socio-economic factors. A lot has changed in Japan especially for younger cohorts of highly educated women. As Figure 3 shows, women's enrollment in 4-year universities started to increase after the legislation of the EEOL in 1985. Once the labor market penalty of 4-year university education decreased, the number of female high school graduates who decided to continue their education increased very rapidly. By the early 2000s more than 30% of 18-year-old women were enrolled in 4-year universities rather than junior colleges. The shrinking of the young age cohorts due to the continued decline in Japan's total fertility rate since the 1980s has led large corporations to hire more university-educated women. In particular, the labor market environment for the cohort of university-educated women born in the 1980s and later has become much more favorable than what the previous cohorts faced.

Figure 3. Four-year university enrollment rate of 18 year olds.

Source: Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Basic Statistics of Schools, https://www.mext.go.jp/content/20201126-mxt_daigakuc02-000011142_9.pdf.

Women's occupational choices changed accordingly. The ranks of young women interested in professional careers grew. When we look at journalists and lawyers – two occupations common among Diet members – we observe a rapid increase in the share of women since 2000. Only 3.7% of lawyers were women in 1980, but the share rose to 8.9% in 2000 and then to 18.9% in 2019 (Japan Federation of Bar Associations, 2019: 44). As for journalists, the female share was only 0.7% in 1980, but it rose to 10.2% in 2000 and then 23.5% in 2021.Footnote 2 These figures indicate that the EEOL legislated in 1985 did not improve the career prospects of women in the birth cohort of 1960s and the early 1970s, but it helped women in later birth cohorts reap the fruit of their educational investment.

As women increased their educational investment, many of them also delayed or forewent marriage and motherhood. In discussing the gender revolution in the USA, Claudia Goldin (Reference Goldin2006) notes how crucial it was for young women to establish their own identity through their professional experience before becoming mothers. Young women who had established their identity as professionals would try to hold onto their jobs even after marriage and childbirth. While this shift in the USA occurred to women of Hillary Clinton's generation – the generation who came of age during the 1960s – it only occurred to those who came of age after the mid-1990s in Japan. The timing of this shift in Japan explains why both the supply and demand for female politicians increased in the 2000s and 2010s.

Today the average ages of first marriage and motherhood are much higher in Japan than before. This is because, younger women stay at school and at work for more years before getting married and having children. The trend is more pronounced in Tokyo. In 2019 in Tokyo, women marry on average at 30.5 years old and become mothers at 32.2 – older than the corresponding national averages of 29.6 and 30.7.Footnote 3 Back in 1985, the average age of women at their first marriage in Tokyo was 26.3 and the national average was 25.5.Footnote 4 As the number of women who formed their identity as professionals increased, so did the number of dual-earner families where both the husband and the wife worked full-time. Two factors have been critical in expanding young women's choices: one, investing in university education; and two, getting a full-time regular job. In total, 49.5% of university-educated women married to university-educated men now have full-time regular jobs.Footnote 5 The figure is 52% for women aged 35–44. In contrast, when we also include women with less than university education married to university-educated men, the share of wives with full-time regular jobs drops to 36.4%.

Interestingly, while Tokyo still has a high rate of unmarried women aged 30–34, the marriage rate has started to rise. Tokyo's rate of unmarried women aged 30–34 was 19.5% in 1985, 42.9 in 2005, and 39.5% in 2015.Footnote 6 Many educated young women who get married no longer necessarily accept the same gender pact of their mothers' generation. University-educated women in Tokyo, where the best career options exist, are increasingly willing to balance parenthood and career. Although many highly educated women in Japan still quit their jobs upon marriage or motherhood, the number of women who hold onto their jobs has increased. According to the most recent Gender Equality White Papers, the share of women who stay at the current employment after becoming mothers has increased from 39.2% during the 1985–1989 period to 53.1% in the 2010–2014 period.Footnote 7 When we look only at women who have regular full-time jobs, the change between the two periods is even greater – an increase from 40.7 to 69.1%.Footnote 8 In 2007, only 17% of mothers of small children (0–5) worked in full-time regular jobs, but the share increased to 27% in 2017. The change in women's labor market behavior has been slow to arrive in Japan but it is finally happening. Kuga (Reference Kuga2017) notes that the number of high-income dual-earner couples has been on the rise. Due to the concentration of well-paid professional jobs in Tokyo, these couples tend to reside in areas of Tokyo within short commutes to business districts such as Marunouchi.

The electoral demise of the Netto women dates to the 2007 local elections. That year, ironically, marked the beginning of the third stage of rise in female political representation in Tokyo's Special Wards. Although the decline in the number of university-educated housewives hurts the Netto, new electoral opportunities were emerging for younger women. The realignment of party system was under way as the female population in Tokyo was becoming more heterogenous, and the timing of these two changes proved to be important for female political representation in Tokyo.

The emergence of the DPJ as the biggest challenger to the LDP in national politics created a new demand for electoral candidates at the local level. As already mentioned, unlike the JCP and the Komeito, the DPJ had no solid organizational basis aside from the backing of moderate corporate unions. This meant that recruitment of good candidates for all levels of elections – particularly local elections – presented a lot of difficulties for the DPJ. As the DPJ began to differentiate itself from the LDP as a party more responsive to the needs of urban voters, civic leaders who were lobbying municipal governments for more assistance with childcare or better urban planning became very attractive candidates for the DPJ. Many of these civic leaders were working mothers with professional careers. When the 1999 local elections resulted in a big increase in the number of local assembly women in Tokyo's Special Wards (see Figure 2), the DPJ played an important role as a recruiter of female candidates in addition to the Netto, the JCP, and the Komeito. Furthermore, during the 2000s, it became increasingly clearer that female voters in Tokyo no longer consisted of housewives (and future housewives). The DPJ positioned itself to appeal to younger more heterogenous cohorts of female voters in Tokyo by fielding new types of female candidates such as female community activists, female staffers of Diet members, and professional women with prior media exposure such as freelance TV casters. As the DPJ strengthened its electoral position in urban local elections, their success also prompted the LDP to readjust its electoral pledges and candidates in local elections in Tokyo. Oki (Reference Oki2008) and Shin (Reference Shin2020) note that even the Netto, originally a movement of urban housewives, has since modified their recruitment strategy by diversifying the pool of candidates to include professional women. Today the Seikatsu Club, the Netto's ‘mother-organization,’ offers new offshoot activities including childcare services in their attempt to recruit younger members. However, the Netto has not been able to regain their electoral fortune.

In short, the composition of female voters in Tokyo was changing rapidly in the 2000s as the electoral landscape in Tokyo was also becoming more competitive. It was this combination of factors that contributed to the rise in the share of female politicians in Tokyo even after the Netto's historical role was coming to an end. The next section turns to how the Netto's ‘housewife politicians’ came to be replaced by a new type of female local politicians, who were ‘working mothers’ (Mama Giin).

5. Rise of Mama Giin: the new supply and demand

The social transformation described in the previous section has impacted the electoral strategies of political parties. Politically speaking, the greater educational and career investments by younger women affected both the supply and demand sides of local politics in Greater Tokyo. On the supply side, the number of high-quality female candidates with professional experience willing to run for local elected office grew dramatically in the past 20 years. At the same time, the increase in young professional women who want to continue working past childbirth led to a greater demand for public services such as childcare services, after-school programs, and daycare services for sick children.

Supply and demand-side factors explain why the rise in female representation is most salient in Tokyo area. On the supply side, Tokyo has a higher share of university-educated women (and men) than in the rest of the country. This happens partly because of two reasons. One is the concentration of universities in Greater Tokyo, which makes it cheaper for young people from Tokyo families to attend university while living at home. The other reason is the concentration of good corporate jobs in Tokyo, which attracts young people from the rest of the country. On the demand side, the stronger labor market attachment of highly educated women and the rise in the share of dual-full-time-earner families in Tokyo increases the demand for policies catering to the needs of such families. Because multi-generational households are less prevalent in Tokyo, the availability of childcare – especially full-day care – is a lifeline for working mothers in Tokyo (Iwamoto, 2011). After the legislation of EEOL in 1985 and especially during the 1990s, the national government began to respond to the rise in the number of working mothers by expanding eligibility to publicly subsidized childcare places and by deregulating the entry requirement for childcare center operators (Estévez-Abe, Reference Estévez-Abe2008; Sunahara, Reference Sunahara and Takenaka2017). The more daycare services the government provided, the greater the number of young mothers who desired to hold onto their careers. This dynamic has given rise to a phenomenon that the Japanese call ‘Taiki Jido Mondai (the childcare waiting list problem).’ The problem was particularly acute in those areas of Tokyo where many young dual-career couples resided thereby making it very difficult for these couples (particularly women) to balance childcare and career. Mothers with children with chronic health issues or disabilities faced even greater hardship. Some of these young mothers became local activists and ran for local elections as independents or were recruited by the DPJ, which was on the lookout for good candidates to take on the LDP. These mothers – many of them working mothers or those who had to give up their careers – gave rise to Mama Giin.

Mama Giin are female politicians who seek highly educated working mothers' votes by emphasizing their sameness: they share the same struggles, the same frustrations, and the same disappointments of trying to balance career aspirations and childcare responsibilities. In other words, Mama Giin are not just female politicians who happen to be mothers but those whose message to voters stresses their status as professional working mothers and their lived experience of struggling to balance parenthood and career. In the 2010s, working mother politicians – Mama Giin – have replaced the Netto's housewife politicians as a new group of female local politicians who represented ‘ordinary women.’ It should be clearly noted here that Mama Giin are not the only type of new female politicians. However, many women who become Mama Giin are from the same socio-economic group that had once produced housewife politicians, and, as such, provide us with a useful perspective to compare how Japan's political women have changed.

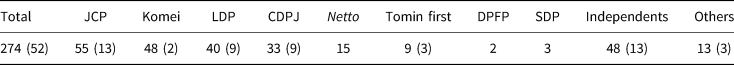

Table 1 shows the number of Mama Giin and the party breakdown of female politicians elected in the latest round of elections in Tokyo's 23 Special Wards.Footnote 9 Of the 274 assembly women in the 23 Special Wards, I have been able to find personal websites and social media profiles of 260 of them. I then identified those who highlighted their experience and struggles as working mothers and their advocacy of policies for parents. Many of them present detailed narrative of who they are and why they became politicians offering a great source of information that used to be only available by interviewing politicians. On the basis of the personal narratives listed in their websites, 52 of these 260 women fit my definition of Mama Giin. All of these women prominently display their status and experience as working mothers in their websites and posters, promise to change politics for working mothers, and some even use the term Mama Giin to describe themselves. Female politicians, who are mothers, do not count as Mama Giin as defined here, unless they highlight their status as working mothers in their messaging to voters.

Table 1. Party breakdown of female winners and the number of Mama Giin (in parentheses) in the latest Special Ward elections

JCP, Japan Communist Party; Komei, Komeito; LDP, Liberal Democratic Party; CDPJ, Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan; Netto, Seikatsusha Nettowa-ku; Tomin first, Tomin first no Kai; DPFP, Democratic Party for the People; SDP, Social Democratic Party.

Source: The data have been compiled by the author from the detailed election results posted at https://seijiyama.jp as well as the personal websites of the assembly women.

Unlike the housewife candidates from the Netto in the 1990s, Mama Giin are a heterogenous group when it comes to partisan affiliation. As Table 1 shows, Mama Giin are found among assembly women from the JCP, the Komeito, the LDP, the CDPJ (Rikken Minshuto), Tomin Fasuto, and independents. However, the number of the Komeito's Mama Giin is negligible. This is not very surprising as Komeito candidates rely on their organizational votes and hence do not need to appeal to other voters.

The last local elections in 2019 highlight how successful female candidates were in Tokyo. All Special Wards held their assembly elections in 2019 except for Katsushika ward. Of the 22 ward-assembly elections, the top vote getters were women in 12 of them. Mama Giin were the top vote getters in five of them. The number of Mama Giin from the LDP in Table 1 might come as a surprise. As the section below explains, this reflects an attempt by the LDP to emulate the DPJ's success. In the Tokyo local elections in 2007, 2011, and 2015, the DPJ recruited more female candidates than its rival LDP and these female candidates had done well. By the 2019 local elections, the new party Tomin Fasuto opted for fielding more women and the LDP had also increased the number of female candidates – including Mama Giin. As the DPJ broke up into multiple parties, the LDP even recruited one of the former DPJ Mama Giin to run as an LDP candidate in 2019. This indicates how the LDP was trying to appeal to the same group of female voters that the DPJ had successfully captured in some electoral districts in Tokyo.

The DPJ was the pioneer of fielding Mama Giin, but both the LDP and the JCP gradually emulated the strategy. The DPJ, as a new party, fielded younger women some of whom were harbingers of Mama Giin. The average age of the DPJ's female assembly women for the new-comer DPJ were 48.1 and 48.6 after the 2007 and 2011 local elections, respectively. In contrast, the average ages for the female assembly women affiliated with the JCP and the Komeito and the LDP were much older: 53.8 and 54.3 for LDP, 54.5 and 55.6 for the Komeito, and 54 and 55.7 for JCP after the 2007 and 2011 elections, respectively. As the DPJ successfully elected female candidates, the LDP began to recruit younger women. By the 2019 local elections, the age gap between the LDP and the CDPJ (the most gender egalitarian of the successor parties of the DPJ) politicians had significantly narrowed. The average ages of the first-term assembly women in cities and Special Wards were 47.7 and 47.1 for LDP and CDPJ, respecitvely (Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai, Reference Ichikawa Fusae Kinenkai2019: 37). The JCP too started fielding younger female candidates although the majority of candidates were older women who had moved up through the ranks within the party organization. The aging of their organizational membership prompted the JCP to field younger candidates as a way to attract younger voters. Some of the young female candidates were Mama Giin who appealed to voters by connecting to them with the shared experience as ‘working mothers.’ That said, all JCP candidates for local elections including Mama Giin run on the same policy platform which emphasized issues common to all workers and the importance of equal treatment of all workers (men and women).

6. Paradox of New New Women: biographic profiles of Mama Giin

A paradoxical combination of the social advancement of Japanese women and unchanging patriarchy lies at the core of the emergence of Mama Giin. Highly educated young women have a lot more options today than their mothers' generation. At the same time, little has changed in the domestic role of women because large corporations have been slow to change their practices, which are more suitable for male breadwinners with stay-home wives. Highly educated women who want both a family and a career ‘look to daycare as the solution for the hours that companies demand’ to borrow Gill Steel's astute observation (Steel, Reference Steel2019). In other words, rather than demanding that their employers and their husbands change, they demand that public authorities provide more daycare slots and varied daycare services (such as looking after a sick child or staying open longer, etc.).

As the following biographies of selected Mama Giin illustrate, a good share of the Mama Giin ran for office because it became too difficult for them as mothers to reconcile the demands of work and family. Compared to corporate life, the life of a local politician can be more child-friendly. In fact, those Special Wards such as Chuo ward and Minato ward right next to Tokyo's business districts – ideal locations for university-educated dual-career couples with children – have higher shares of Mama Giin. The largest concentration of Mama Giin is found in Minato ward – a ward in the very center of Tokyo where many affluent dual-earner families live for the convenience of a short commute. The Minato ward elected 13 women in 2019 of which six are Mama Giin and no Netto housewife politicians. A close examination of seven Mama Giin – including three who were the highest vote-getters in their Special Wards – reveals who they are and why they decided to run for office. Here I mostly focus on LDP and DPJ women and contrast them to Mama Giin in the JCP only at the end.

The top vote getter in Minato ward, Ai Seike, is a Mama Giin. Her biographical profile is representative of a university-educated career-oriented woman who encountered difficulties in balancing work and family because of what she perceived as the failure of local government to improve the public infrastructure for working mothers. Ai Seike (born in 1974) graduated from Aoyama Gakuin University in Tokyo and joined Sankei Shimbun as a journalist.Footnote 10 In Japan, joining a national newspaper company or a TV company is highly competitive as career-track jobs in these companies are few, well-paid, and high status. However, a career as a journalist involved long and unpredictable hours and Seike found it difficult to balance her family life after she got married and had a child. She quit Sankei to become a freelance journalist instead. However, due to the long queue in the waiting list for a daycare spot in Minato ward, no place was available for her child forcing her to quit work altogether. She started a network of working mothers in Minato ward called Minatoku Mothers' Group and successfully ran for a seat in the local assembly as a DPJ candidate in 2011. She was reelected in 2015 and yet again in 2019 as an independent after the split of the DPJ.

Seike's fellow Minato ward assembly member, Aki Yanagisawa, also fits this description. Aki Yanagawa (born in 1981) graduated from Kagawa University and joined Shiseido, a cosmetics company long known for hiring women for career-track positions (Sogoshoku).Footnote 11 Yanagisawa worked for Shiseido as a career-track professoinal and experienced various assignments while she saw many of her colleagues quit due to difficulties in managing the work–family balance. She continued to work post-marriage but when she became a mother, she came to realize how hard it was for a new working mother to secure a daycare spot for her child in order to go back to work. She researched and discovered that Minato ward had the longest waiting list for daycare spots in Tokyo, and she decided to run for local assembly herself in 2011. She first ran and was elected as a DPJ candidate but switched parties and was re-elected twice in 2015 and 2019 as an LDP candidate. During her first term, she got divorced and became a single mother and did something unusual in Japan – she changed her last name back to her maiden name. She portrays herself not only as a working mother but a single mother and vows to make life easier for all mothers.

The top vote getter in Meguro ward, Hiroko Yamamoto (born in 1976), has a similar story.Footnote 12 She graduated from Saitama University and spent a few years working although her priority was backpacking in foreign countries during holidays. She then studied to become an IT specialist and landed an IT job in a foreign financial institution. Yamamoto got married and had three girls. She held onto her IT job because she managed to secure daycare places for her children. Although she herself was fortunate to find the necessary daycare slots, she nonetheless found the process of finding and qualifying for daycare places unreasonably daunting for working mothers. Yamamoto strongly felt that it should not be so difficult for working mothers to find a daycare place and decided to run for local assembly to change the system. She makes a statement very similar to Yanagawa in the Minato ward. When she decided to run, the Meguro ward had the longest waiting list for daycare places in Tokyo (she was first elected in 2015). Yamamoto initially ran as a DPJ candidate and ran as a CDPJ candidate in 2019 after the split of the DPJ. Her poster prominently advertises her as an IT engineer and a mother of three children. Her policy slogan goes beyond work–family policies and includes bringing technology to local government. After securing the highest number of votes in her reelection bid in 2019, she unsuccessfully ran for the mayor of the Meguro ward.

Some Mama Giin also have had international work experience. Some of them, like Yamamoto, worked for foreign companies in Tokyo, but others had professional experience abroad. Risa Kamio (born in 1982) graduated from Seishin Women's University and then left for the USA to work as a Japanese language instructor. After a few years of working as an educational travel coordinator, she worked for 10 years as a director of educational programs at The Japan–America Society in Washington, D.C. She came back to Japan in 2018 as a working mother and was astonished how difficult life was in Japan so decided to run for local assembly in Setagaya ward as an independent. Her appeal was her overseas experience. She appealed to voters as a working mother and as someone who could internationalize Setagaya by building a more inclusive society.

Some of the Mama Giin became politicians while advocating for their special needs children. Mari Seo of Shinagwa ward and Yuko Hyodo of Minato ward provide examples of such cases. Mari Seo (born in 1977) graduated from Seikei University and then went to a nursing school and become a certified nurse working in a hospital. She got married but could not conceive a child so shifted to part-time work to devote more time to infertility treatment. Her first born child had special needs and she came to identify problems in the way the government was handling services to families with children like her son. Seo began to connect with other mothers in similar situations and lobbied Kyoko Morisawa, an assembly woman in the Tokyo Prefectural Assembly, who encouraged her to run for local office herself. This led to her candidacy. She ran for local assembly for the first time in 2019 and was elected.

Yuko Hyodo (born in 1967), although older than other Mama Giin who have younger children, is a Mama Giin in the sense that she is still caring for her disabled son. She graduated from Tokai University and joined a cosmetics company. She raised twins while she continued working but then one of her parents became ill requiring personal assistance. She also discovered one of her twins had cognitive disabilities. Around the same time, the company she worked for merged with another drastically affecting her working conditions. She became keenly aware of the limits of self-help and became interested in government services for children with medical and other special needs. In 2015 she ran as a DPJ candidate and was elected. In 2019, she was reelected as a CDPJ candidate.

Other Mama Giin consist of the youngest group of mothers who worked in the private sector but decided to run for local assembly and then became mothers once in office. This group of women ran for office on the basis of their professional expertise while also promising to improve conditions of working mothers. Sayo Honme represents this group. Sayo Honme (born in 1982) was the top vote getter in Taito ward in the 2019 election.Footnote 13 She is slightly different from the previous Mama Giin whose biographies we have already discussed. Honme, too, was a working mother before she ran for local assembly in 2011 as a DPJ candidate. She was working in the human resources department of an IT company and dealt with female employees who encountered difficulties in returning from maternity and parental leaves as they struggled to find daycare slots for their children. Unlike the other Mama Giin examined so far, Honme has a Ph.D. in psychology and her dissertation investigated how fathers' participation in childcare alleviated the mothers' stress caused by childrearing. The combination of her academic knowledge and workplace experience of seeing multiple cases of working mothers leaving employment motivated her to pursue a career in politics. She was elected as a DPJ candidate in 2011 and has been reelected twice since. Like Seike in Minato ward, Honme decided to run as an independent after the split of the DPJ. Unlike Minato ward, which elected six Mama Giin, Honme is the only Mama Giin in Taito ward.

The biographies of Mama Giin support the view that the social changes discussed in this paper did indeed change the supply of female political candidates as well as the demand for policies. While some young women ran for office first and became mothers while serving their legisltive terms, many highly qualified women became politicians to fight the system that had failed them. The latter group includes Mama Giin like Ai Seike, who found it impossible to combine her profession in journalism with motherhood. What stands out from their biographies is that most of the Mama Giin complain little about the corporate system or the persisting patriarchy in Japan. They seem to accept the fact that mothers are primarily responsible for childcare. In this sense, they contrast starkly against other types of female politicians – from their own parties sometimes – who take issue with what they perceive to be more structural problems in the Japanese economy and governments. In their acceptance of mothers' responsibility and scant reference to fathers, they resemble Pharr's ‘New Women’ more than ‘Radical Egalitarians.’ We hence might call these Mama Giin ‘New New Women.'

It is worth noting that the JCP's Mama Giin are slightly different. Mama Giin from the LDP and the DPJ are clearly signaling to university-educated women in relatively high-income dual-earner households or divorced mothers from such households. They tend to be elected in affluent Special Wards. In contrast, JCP's Mama Giin are elected from less affluent Special Wards. While they talk about their struggles as working mothers and are clearly signaling to working mothers in their districts, they also highlight the overall gender inequality in Japan and talk about how female wages should be raised. The JCP's Mama Giin are the only ones that express their opposition to Japan's patriarchy. In this sense, the JCP's Mama Giin are the same as the rest of the JCP politicians in their Radical Egalitarian gender norms.

7. Conclusion

This article has investigated how the social transformation that changed Japanese young women's life course decisions also diversified the types of women who could run for local elected office in Japan – especially in Tokyo. While the number of Netto's housewife politicians has been in decline in Greater Tokyo, the number of professional women who run for local office has been on the rise since the 2010s. Some of these women fall into the category of Mama Giin as defined in this article. They are female politicians who had established themselves as professional women before becoming mothers and explicitly promote themselves as advocates for other working mothers. Their rise in Tokyo is not a coincidence. As this article has demonstrated, the concentration of educational and professional opportunities in Greater Tokyo has led to the rise in the number of career-oriented women and dual-career couples. The supply and demand for female politicians have thus changed more dramatically in Tokyo than elsewhere.

Mama Giin, who are ‘professional women,’ contrast sharply with their mothers' generation, who primarily took part in local politics as ‘housewives’ and ‘consumers.’ In this sense, they represent the changing face of Japanese women. At the same time, however, their biographies are marked by conflicting forces facing Japanese women: opportunities have expanded for women – especially those who can work male-breadwinners' hours – but most of the childcare responsibilities still primarily fall upon women in Japan. Mama Giin – except for those affiliated with JCP – choose to solely focus on the failure of the government in providing adequate childcare services rather than question the Japanese corporate life or patriarchy in Japan. Mama Giin appear to be ‘good daughters’ of Pharr's ‘New Women’ and this is why I have called them the ‘New New Women.’ This does not, however, mean that they are not ambitious. One of the Mama Giin discussed in this article, Hiroko Yamamoto of the Meguro ward, ran for a mayoral race in her special ward. Although Yamamoto lost her bid, her story shows that when the pipeline of female local politicians grows bigger, more women as Yamamoto will emerge. Indeed, a few of Mama Giin who won ward-level local assembly seats in 2019 successfully ran for Tokyo Prefectural Assembly in 2021. Tsuji (Reference Tsuji2017) also chronicles a new trend: more and more women are running for mayoral and gubernatorial races in Japan. Someone like Yanagawa of the Minato ward, who switched her party affiliation from DPJ to LDP, is likely to be seeking to move up.

Although this article has focused on the rise of Mama Giin, other types of female politicians have been successfully running for local office (Oki, Reference Oki2019). Political parties are beginning to field specific types of younger candidates to appeal to specific groups of younger voters. Given the low turnout rates and low electoral thresholds in local elections, the payoff for a strategy to field candidates who cater to each sub-population of voters can be large. Characteristics of local politicians have thus become much more diverse reflecting the diversity of voters in Tokyo. Whether the diversity in local assemblies in Tokyo can extend to the national political scene is an important question. The case study of local assembly in Tokyo suggests that it is unlikely as far as the LDP's dominance continues under the current electoral system based on small district magnitude.

Conflict of interest

The author declares none.