Introduction

Suicide is a global health concern. In the Republic of Ireland, 506 people died by suicide in 2016 ( Central Statistics Office). Young men (15–39 years) and middle-aged women (45–55 years) have been considered traditionally to be at highest risk of suicide (Malone, Reference Malone2013), but in the last decade in Ireland, 45–55 years is the highest risk age group for both men and women ( Central Statistics Office).

The Irish National Self-Harm Registry has highlighted a concerning trend in recent years, demonstrating an increasing proportion of self-harm presentations involving high-lethality methods (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, McTernan, Wrigley, Nicholson, Arensman, Williams and Corcoran2019; Joyce et al. Reference Joyce, Daly, McTernan, Nicholson, Griffin, Arensman, Williamson and Corcoran2020). Recent US data suggest that increased suicide rates are associated with both an increased incidence in suicidal acts (i.e. completed and attempted suicide) and increased use of higher-lethality methods (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Sumner, Simon, Crosby, Annor, Gaylor, Xu and Holland2020). Furthermore, while overdose is viewed as a low-lethality method, and women are more likely to use this method than men (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, McTernan, Wrigley, Nicholson, Arensman, Williams and Corcoran2019), a national case fatality study of intentional drug overdose demonstrated that male sex is associated with a fatal outcome (Daly et al. Reference Daly, Griffin, Corcoran, Webb, Ashcroft, Perry and Arensman2020). This is consistent with the well-documented suicide paradox: suicide attempt rates are higher among females, whereas lethality is higher among males (Stone & Crosby, Reference Stone and Crosby2014).

Psychological autopsy and record linkage studies have led to a greater understanding of risk factors for completed suicide, including mental disorders (in particular mood, psychotic and personality disorders) (Too et al. Reference Too, Spittal, Bugeja, Reifels, Butterworth and Pirkis2019) and physical illness (Webb et al. Reference Webb, Kontopantelis, Doran, Qin, Creed and Kapur2012; Qin et al. Reference Qin, Agerbo and Mortensen2013). However, suicide is a complex phenomenon and survivors of high-lethality suicide attempts may be a clinical proxy for understanding more about completed suicide (Hawton, Reference Hawton2002; Gvion & Levi-Belz, Reference Gvion and Levi-Belz2018). This approach has several advantages which include investigating the psychological processes leading up to the suicide attempt, and following survivors and their treatment outcomes (Gvion & Levi-Belz, Reference Gvion and Levi-Belz2018).

A small but increasing body of longitudinal research is investigating the association between the lethality of a suicide attempt and eventual death by suicide, and high-lethality methods confer an increased risk of future completed suicide (Runeson et al. Reference Runeson, Tidemalm, Dahlin, Lichtenstein and Långström2010; Beautrais et al. Reference Beautrais, Larkin, Fergusson, Horwood and Mulder2012). A cross-sectional study of high-lethality suicide attempts in Korea has shown that age and previous suicide attempts using a high-lethality method were independent predictors of attempted suicide using a high-lethality method (Oh et al. Reference Oh, Lee, Kim, Park, Kim and Kim2014).

To date, research involving high-lethality suicide attempters has tended to compare high-lethality attempters with non-suicidal psychiatric or general populations, which limits the ability to understand how high-lethality attempters differ from low-lethality attempters (Gvion & Levi-Belz, Reference Gvion and Levi-Belz2018). This study hopes to add to the small body of literature comparing high-lethality attempters to low-lethality attempters and suicide ideators. We hypothesised that high-lethality attempters will align more closely to the demographic and clinical features observed in completed suicide in the national and international literature (i.e. male, middle-age, psychiatric diagnosis, previous attempt and medical comorbidity) compared to low-lethality attempters and ideators. In addition, we aimed to explore other possible demographic (e.g. deprivation status) or clinical [e.g. history of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (NSSI) and engagement with psychiatric services] differences between high-lethality attempters, low-lethality attempters and ideators.

Methods

Study design and sample

A retrospective random analysis of adult (≥18 years) suicide ideators and attempters presenting to a Dublin university hospital over a 1-year period (1 January 2017–31 December 2017) was performed. The hospital serves a local catchment area of approximately 600 000 people. All referrals to the Liaison Psychiatry team were identified by reviewing the team’s record of referrals – an Excel spreadsheet which categorises referrals by reason of referral to the team. All referrals for suicidal ideation (n = 327) and self-harm/suicide attempt (n = 488) in adults were identified.

The medical records of referrals were reviewed (randomly, according to increasing medical record number) to identify 50 suicide ideators and 50 suicide attempters (vs. presentations of self-harm/non-suicidal self-injury) for inclusion in this study. Fifty suicide attempters were identified after reviewing a total of 75 referrals categorised as self-harm/suicide attempt. Repeat presentations were not excluded from the study.

Medical records at the study site are stored in the form of both paper (e.g. inpatient notes) and electronic (e.g. MAXIMS – Emergency Department software; Microsoft Office Word Documents – Liaison Psychiatry assessments) records. Anonymous data collection was performed by authors AD and NC by reviewing electronic and paper medical records for each presentation. An Excel proforma was used to extract the following data for the final sample (n = 100 presentations): date of presentation, hospital medical record number, sex, age, deprivation index, method and lethality of suicide attempt, history of previous suicide attempt, history of non-suicidal self-injury, psychiatric diagnosis [i.e. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) Axis 1 or 2, American Psychiatric Association, 2000] physical health diagnoses, current engagement with mental health services, psychiatric outcome and reattendance during period of study. Data extraction for the first five presentations was performed by both AD and NC to establish interrater reliability, which was 100% on all variables.

Measures

Method and lethality of suicide attempt were coded using the medical Lethality Rating Scale (LRS) (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Beck and Kovacs1975), which has been demonstrated to have adequate inter-reliability (r = .80) (Lester & Beck, Reference Lester and Beck1975). The LRS rates the medical severity of an attempt using a scale of 0 (no/minimal consequences) to 8 (death). Anchor points are different and specific for each type of method, but for all methods high-lethality attempts are defined as a lethality score ≧4, which equates to injury requiring hospitalisation. Deprivation indices were assigned based on Pobal HP Deprivation Indices (https://maps.pobal.ie), a national Geographical Information System. The Pobal HP Deprivation Indices assign addresses in Ireland a category (from extremely disadvantaged to extremely affluent).

Statistical analyses

Statistics were performed using JASP (Version 0.14.1). Independent one-way ANOVA was performed to compare age between groups. Pearson’s chi-square test was performed to compare the categorical demographic (sex and deprivation index) and clinical characteristics (psychiatric diagnosis, history of NSSI, previous suicide attempt, engagement with psychiatric services and physical health comorbidity) between ideator, and low- and high-lethality attempter groups. An exploratory analysis, using Pearson’s chi-square test, investigated differences in psychiatric management between groups.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

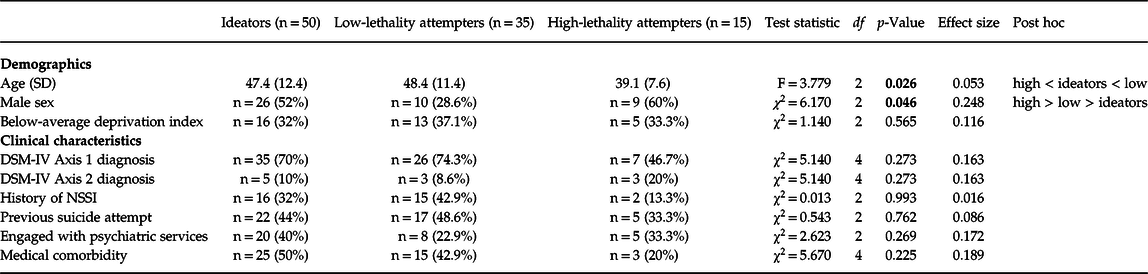

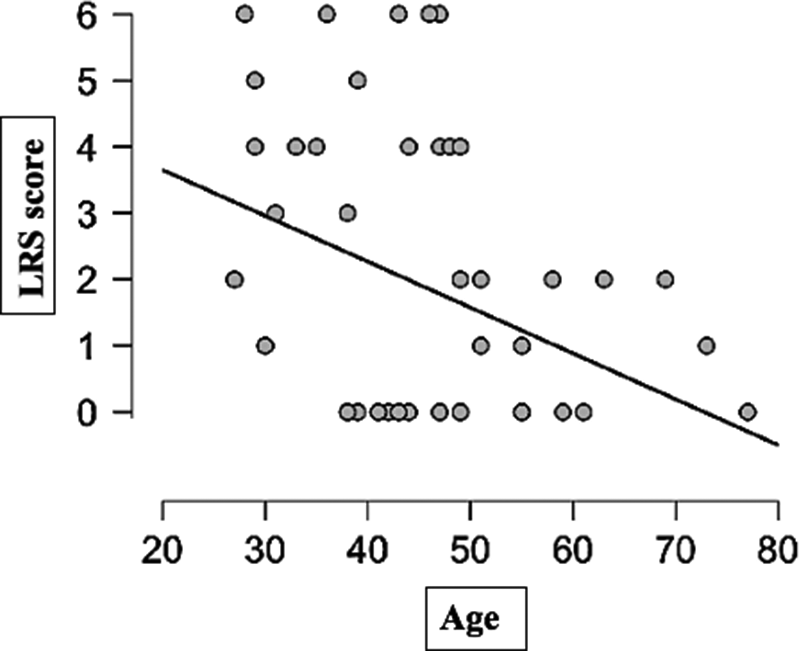

Table 1 summarises the comparisons between ideators, low-lethality attempters and high-lethality attempters. Independent one-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of group on age (F (2,97) = 498.858, p = 0.026, η2 = 0.072 with an effect size (ω2) of 0.053. Post hoc testing using Tukey’s correction revealed that high-lethality attempters were significantly younger than both low-lethality attempters (p = 0.026) and ideators (p = 0.041). There was no significant difference in age between low-lethality attempters and ideators (p = 0.910). In suicide attempters, a significant correlation was found between the LRS and age (rs = −0.335, p = 0.017; see Fig. 1).

Table 1. A comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics in ideator, low-lethality attempter, and high-lethality attempter groups

SD, standard deviation; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; NSSI, Nonsuicidal Self-Injury; df = degrees of freedom. Bold values indicate statistical significance (i.e. p < 0.05).

Fig. 1. Lethality of attempt (Lethality Rating Scale score) vs. age (years).

The highest proportion of male subjects was in the high-lethality attempters group (60%). Pearson’s chi-square test demonstrated a significant effect for sex between groups (χ2 (2) = 6.170, p = 0.046) with an effect size (Cramer’s V) of 0.248. Post hoc testing using a standardised residual showed that while more men were observed in the high-lethality (z = 0.87, p > 0.05) and ideator (z = 0.73, p > 0.05) groups than expected, and less men were observed in the low-lethality group than expected (z = −1.45, p > 0.05), the difference between expected and observed counts in each group was not significant. There were no significant between-group differences in terms of deprivation index, psychiatric diagnosis, history of NSSI, previous suicide attempt, engagement with psychiatric services and physical health comorbidity.

Psychiatric management

An exploratory analysis using Pearson chi-square test was performed looking at differences between groups in psychiatric management (i.e. psychiatric admission, outpatient follow-up, discharge to GP/other service and left against medical advice) following the index presentation. There was no significant difference between groups (χ2 (3) = 2.695, p = 0.441) in terms of psychiatric management with similar proportions of each group referred for psychiatric admission (ideators n = 12, 24%; low-lethality n = 7, 20%; high-lethality n = 5; 33.3%) and outpatient follow-up (ideators n = 23, 46%; low-lethality n = 17, 48.5%; high-lethality n = 5, 33.3%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Ireland to identify younger age as a predictor of higher-lethality suicide attempts using a standardised Lethality Rating Scale. However, except for a higher proportion of males in the high-lethality group (non-significant), high-lethality attempters did not differ from low-lethality attempters or ideators in other known risk factors for suicide (i.e. psychiatric diagnosis, previous attempt and medical comorbidity), nor other factors explored in this study (deprivation status, history of NSSI and engagement with psychiatric services).

This research complements the Irish data regularly published by the National Suicide Research Foundation. While NSRF’s publications capture all self-harm presentations (i.e. all levels of intent), we have focused on suicide attempts where there is evidence of expressed lethal intent. This study also adds to the small body of literature comparing high-lethality to low-lethality suicide attempters. Understanding the unique group of high-lethality attempters is crucial not least because of the higher risk of later completed suicide (Beautrais et al. Reference Beautrais, Larkin, Fergusson, Horwood and Mulder2012; Fowler et al. Reference Fowler, Hilsenroth, Groat, Biel, Biedermann and Ackerman2012), and the field would benefit from longitudinally followed cohorts of high- versus low-lethality attempters.

Consensus (both clinically, and in the literature) on the interpretation of the concept of lethality, its nomenclature and its measurement, is currently lacking (Gvion & Levi-Belz, Reference Gvion and Levi-Belz2018). Some studies categorise lethality by the method of attempt (e.g. violent or high-risk methods including hanging and drowning, while others categorise lethality by medical outcome, either by using a Lethality Rating Scale, or by establishing a defined cut-off of medical care required to prevent death following the attempt. Invariably, this has limited the interpretations that can be made, or models that could otherwise potentially be drawn, to further understand the risk factors for completed suicide (Gvion & Levi-Belz, Reference Gvion and Levi-Belz2018). Future research would be aided by the widespread acceptance of a definition of high-lethality (or ‘serious’) suicide attempts, which would also enable systematic review of relevant studies. Furthermore, an accepted definition would help the clinician in identifying high-lethality attempters at the time of psychiatric review.

Limitations

Sample size was determined to establish differences between ideator and attempter groups. However, given that the attempter group was subdivided into high- and low-lethality attempters, our small sample size limits the conclusions that can be made and is likely to have undermined power to detect further between-group differences. The study is also limited by its retrospective design, in particular in relation to the assessment of intent and lethality (both of which should ideally be assessed contemporaneously using an objective measure) and reliance on medical record data, which was not always complete.

Conclusions

Our study adds to the small but increasing body of literature investigating the characteristics of high-lethality suicide attempters and suggests younger adult age is a risk factor for a high-lethality attempt. Further understanding of this unique group would be aided by widespread agreement on the definition of a high-lethality suicide attempt, and longitudinal studies of this cohort.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Ethics approval was sought and obtained from the hospital’s Ethics and Medical Research Committee on 23 April 2019.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.