Addressing caregiver mental health in pediatrics

The importance of addressing caregiver mental health needs in pediatric settings

It is well recognized that the mental health of caregivers (parent or other primary caregivers) has direct and indirect consequences for children and that addressing caregiver mental health is critical for their own and their children’s well-being. The connection compels attention within the pediatric hospital (i.e., ambulatory/subspecialty clinics and inpatient) where stress and stakes are high. Caregivers of children with medical conditions may have a greater burden of mental health concerns than caregivers of healthy children (e.g., Bayer et al. Reference Bayer, Wang and Yu2021). Rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and post-traumatic stress symptoms have been found to be elevated relative to caregivers of healthy children in samples of families affected by a range of serious pediatric health conditions (Carmassi et al. Reference Carmassi, Dell’Oste and Foghi2020; Cohn et al. Reference Cohn, Pechlivanoglou and Lee2020; Pinquart Reference Pinquart2019). Similarly, a recent systematic review of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit indicated that 42–53% of caregivers were at risk for one of the measured psychiatric conditions (Yagiela et al. Reference Yagiela, Carlton and Meert2019). Caregivers of ill children report higher levels of parenting stress than caregivers of healthy children (Cousino and Hazen Reference Cousino and Hazen2013) and can also experience changes in employment status and financial burden. The effect of caregiver functioning is pervasive and affects each family member, including the ill child. Thus, interventions developed for caregivers have often prioritized potential benefits to the ill child and their treatment course (Kahhan and Junger Reference Kahhan and Junger2021).

Caregivers routinely receive psychosocial support, but it is generally incorporated within the child’s care and is designed to address basic needs (e.g., housing) or provide supportive psychotherapy narrowly focused on adjusting to the child’s health condition rather than treatment targeting caregiver mental health disorders (Kahhan and Junger Reference Kahhan and Junger2021). For example, caregivers may engage with pediatric medical social workers or their child’s mental health provider (e.g., pediatric psychologist or psychiatrist) who can provide recommendations for their own self-care, help them problem-solve acute issues (e.g., communication with their child’s medical team), or address common needs and reactions to caregiving. Caregivers may also feel supported in other efforts (e.g., patient- and family-centered rounds) related to “family-centered care” which have been employed as a model to enhance psychosocial outcomes for the entire affected family (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Foster and Mitchell2016). However, none of these efforts routinely involve providing separate, but integrated, mental health screening or treatment as advocated by groups such as the National Alliance for Caregiving (2021). This paper describes practical and legal considerations when addressing caregivers’ mental health through screening and intervention delivered within the pediatric hospital setting.

Current state of standards for caregiver support

Some pediatric medical subspecialties are now guided by standards for providing care to caregivers. Many national organizations have adopted protocols for routine mental health screening of caregivers of chronically ill children. One example is the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, which recommends annual screening for at least one primary caregiver for children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis (Quittner et al. Reference Quittner, Abbott and Georgiopoulos2016). Similarly, increasing rates of distress noted in caregivers, and especially in mothers, in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) has resulted in calls for caregiver mental health screening (e.g., Mounts Reference Mounts2009), and the National Perinatal Association described 6 key standards for supporting caregivers of babies in the NICU (Hynan and Hall Reference Hynan and Hall2015). To address the needs of families of children with cancer, the Psychosocial Standards of Care in Pediatric Oncology state that “Parents and caregivers of children with cancer should have early and ongoing assessment of their mental health needs. Access to appropriate interventions for parents and caregivers should be facilitated to optimize parent, child and family well-being” (Kearney et al. Reference Kearney, Salley and Muriel2015). In line with this standard, some pediatric oncology psychosocial programs have begun to identify approaches to meet the standard in ways that meet the needs of their unique patient population and are feasible in their setting (e.g., screening and referral programs or providing treatment to the caregiver on-site).

There is considerable variability in how clinicians can meet guidelines related to caregiver mental health. In subspecialty populations, it may not always be feasible for a pediatric psychologist to meet each individual family, and triage is an important part of getting caregivers to the appropriate resources. In many pediatric settings, other psychosocial providers, typically medical social workers or licensed clinical social workers (LCSWs), are often the first behavioral health provider to be informed of children who are new to the subspecialty or to interface with families. In addition to assessing for basic needs, they often identify mental health concerns among the child or caregivers. In some cases, the LCSW may be able to provide psychotherapeutic support to the caregivers or the family as a whole. However, particularly in the face of more acute mental health concerns, they may refer to, or collaborate with, a pediatric psychologist or psychiatrist for evaluation.

In addition to proactive efforts of members of the psychosocial team, screening programs play an integral role in identifying caregivers presenting with, or at risk for, difficulties with mental health. While screening is increasingly popular, such programs are not without risk of unintended consequences. These include the risk of identifying a caregiver’s mental health condition but not having sufficient resources to help; other risks are discussed in the Legal and ethical section below. Cadman et al. (Reference Cadman1984) proposed criteria for deciding on a screening program including examination of the effectiveness of screening, the availability of treatment options, and the ability of the health system to manage the screening program, among others. A formal caregiver screening program requires developing processes and procedures for selecting, implementing, and responding to the screening measures, in addition to administering the screening. Additionally, appropriate resources must be allocated, and screening tools should be empirically validated. Those administering screens must be identified and trained to implement and respond to screening measures. This includes having the capacity and resources to respond swiftly to urgent and acute matters of safety such as suicidal or homicidal ideation. Finally, clinicians must examine the effectiveness and the availability of follow-up resources for positive screens.

Three proposed pathways to address caregiver mental health in pediatrics

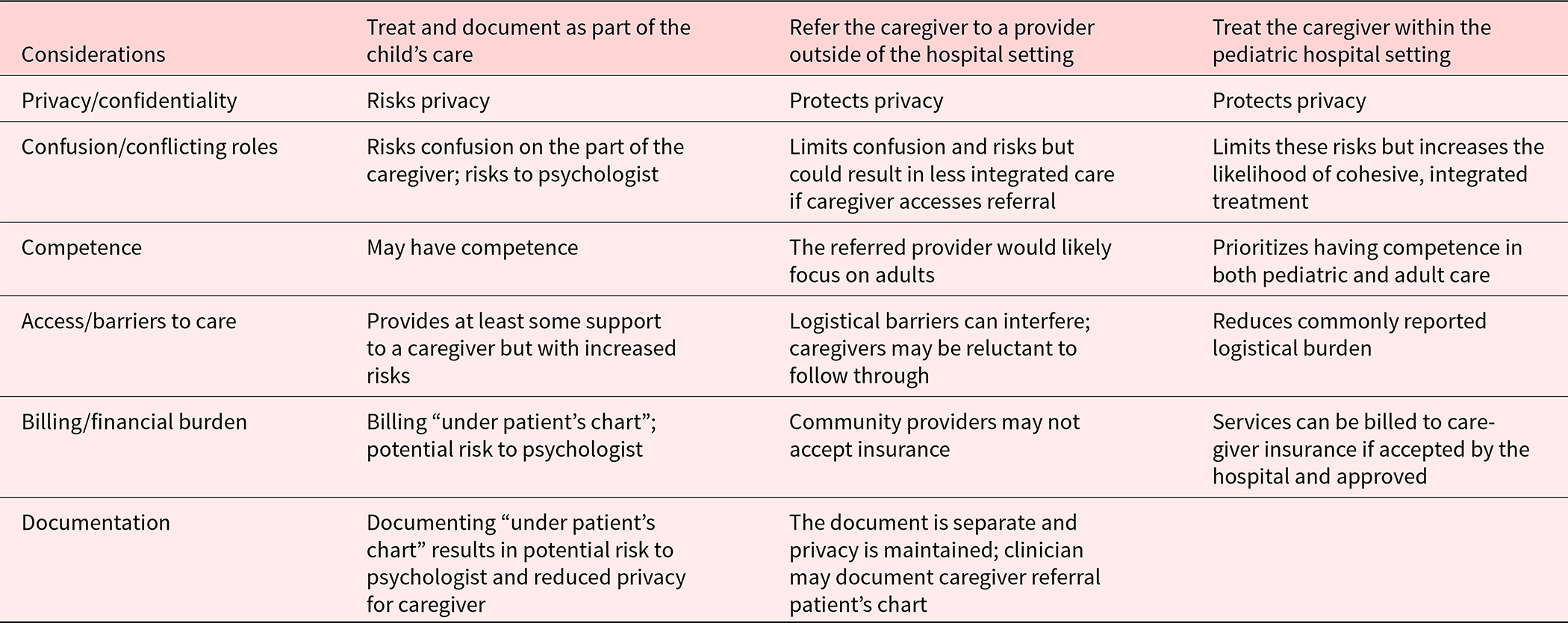

When the need for caregiver intervention is identified by proactive efforts of the psychosocial team, formal screening program, or otherwise, clinicians may follow one of the several pathways, each with strengths and weaknesses. The pathways (see Table 1) most frequently utilized within pediatric hospitals are as follows: (1) subsume caregiver support as part of the child’s care, (2) refer the caregiver to a provider outside of the hospital setting, or (3) treat the caregiver within the pediatric hospital setting.

Table 1. Pathways to address caregiver mental health in pediatric settings

Pathway 1: Treat and document as part of the child’s care

The first pathway, subsuming caregiver care as part of the child’s treatment, is common. Clinicians may use this option when the need for caregiver help is identified through formal screening, by the child’s medical team – who may communicate it informally to the psychologist – or by the psychologist when providing treatment to the child. In this latter case, it may be only upon reflection that the provider realizes they have fallen into the role of a psychologist for the caregiver rather than, or in addition to, the identified pediatric patient. Through the course of treating the child, the provider often gets to know the caregiver well and may be able to provide care to the caregiver in the context of the child’s therapeutic intervention. This can occur when the caregiver’s mental health symptoms are assessed to be primarily situational. Even so, it raises concern regarding conflicts of interest/conflicting roles as it is typically recommended that one provider refrains from treating multiple members of the same family if it could be reasonably expected that the multiple engagements could impair the psychologist’s objectivity, competence or effectiveness, or risks harm to the existing client. (APA code, 3.05(a); see also, 10.02(b)). In most cases, within the community, this is avoided by providing members of family referrals for their own providers even if within the same clinical setting. However, because of the multiple barriers to referring caregivers “out” (see below), the child’s pediatric psychologist may be the most feasible access to a licensed mental health professional available to caregivers. When this approach is used, providers should clearly communicate boundaries, confidentiality, and therapeutic goals with both the child and the parent.

Thus, despite the widespread use, this first pathway and systematic screening come with multiple potential hazards. For example, it is important to attend to caregiver privacy and the practicalities of documentation. Caregiver privacy should be protected in documenting results of screenings or encounters, which is likely to contain protected health information (PHI). Documentation processes should balance the protection of caregiver privacy with the need to share information that is clinically relevant to the care of the child. Other concerns include caregiver consent for the appropriate identified patient (e.g., consenting for their child but actually obtaining treatment for themselves) and billing (e.g., is the child’s insurance being billed when the treatment is specific to the caregiver’s identified mental health needs). Potential solutions for these challenges are often far from clear and accessing system resources and expertise in the areas of compliance, legal/risk, and medical records can be useful. Legal and ethical considerations regarding these hazards are described below.

Pathway 2: Refer caregiver to a provider outside of the hospital setting

A second pathway for addressing caregiver mental health in the pediatric hospital context is to refer caregivers to community providers. This is the least burdensome option for the provider and the pediatric hospital for the long-term, as it significantly reduces the likelihood of conflicting interests that arise from treating multiple related patients, and is essential if the caregiver needs inpatient or intensive outpatient therapy. However, this pathway may require considerable effort and ultimately, often results in caregivers not getting help due to caregiver lack of insurance benefits for mental health; community lack of provider availability; cancellation payment policies (e.g., if the child is unexpectedly hospitalized and caregiver not infrequently has to late cancel a visit); discomfort with leaving their child to access their own appointment outside of the hospital setting; community provider lacking knowledge about child’s health condition and the toll it can take on caregivers; and caregiver reluctance to seek help outside of the child’s core treatment team. Each of these barriers perpetuates unmet mental health needs. If this second pathway must be used, providers may be able to enhance this process by considering the possibility of telehealth for the caregiver and developing collaborative relationships with community providers and a deeper understanding of specialists in the area to whom they might appropriately refer caregivers. Psychologists should consider outreach and providing training to community providers to increase their knowledge of common caregiver presentations and concerns.

Pathway 3: Treat the caregiver within the pediatric hospital setting

Ideally, however, children’s hospitals are moving toward the third pathway: providing mental health care for caregivers on-site. A model that fully integrates caregiver mental health where the child is being treated is the least burdensome for families, as the onus is not on the already struggling caregiver to find a community provider that accepts their insurance, travel to see that provider, and explain their child’s situation to the provider. Thus, this pathway may increase access to care and reduce health disparities. A deeper dive into this third model is presented here.

On-site treatment at the pediatric hospital may be especially effective for caregivers of children requiring frequent or lengthy subspecialty clinic visits (e.g., dialysis or chemotherapy infusion) or during long-term inpatient hospitalizations (e.g., stem cell transplant). Long-term hospitalizations or treatment journeys are uniquely distressing, often prompting an increased need for caregiver mental health care. Mental health needs for caregivers sometimes arise while the child is experiencing serious medical issues, may require significant (caregiver) decisions related to the quality of life, or, in some cases, may be approaching end-of-life. Second, because caregivers are frequently present, hospital staff often become more aware of mental health issues or complex family dynamics that may affect the tenor of interactions with staff or the patient. These challenges may be exacerbated by poor sleep and self-care during hospitalizations and other stressors such as lack of employment and the inability to care for other children as caregivers are needed at the child’s bedside.

A primary consideration of this “bedside” care of caregivers is ensuring that providers are performing within their scope of practice. In order to directly treat psychiatric conditions at the bedside, providers should have the requisite training to engage in assessment, diagnosis, and intervention with the adult population. Experience in crisis situations is necessary, as suicidal/homicidal ideation and/or intent are among the mental health needs that need to be addressed. Other key considerations for bedside care include protecting caregiver privacy and limiting disruption of the pediatric patient’s medical care. If the caregiver is going to be seen in a private location, it is important to coordinate with nursing and other staff so the caregiver can be found if needed. Volunteers, sitters, Child Life, or other staff may be willing to spend time with the child during these visits.

Collaboration with hospital administration is critical to design and implement this model. It may be useful to identify an administrative “champion” who becomes familiar with this service. Additional administrative support may be required to facilitate increased and different kinds of insurance authorizations and billing. With this model, depending on the hospital and payer billing policies, coverage may still be a barrier. Consultation with hospital legal/ethical teams can also be beneficial in designing this model, as these advisors have important perspectives related to insurance (e.g., telehealth regulations), state law (e.g., mental health regulations can vary by state), and ethical considerations.

Clinical judgment may be needed in allocating the psychological services as a resource based on the evaluation of the caregiver, circumstances including barriers to treatment specific to that caregiver, and the scope of the providers’ expertise and availability. Similarly, the psychologist may need to set expectations about the possible limits on the duration of the caregiver’s psychological treatment if the child’s condition improves, upon the child’s death, or if there are other significant changes in the family’s circumstances that may require facilitation of services outside the hospital setting.

Presenting the proposed model for addressing caregiver mental health to other providers in the hospital system to create a widespread understanding of the model will result in improved utilization, coordination of care, and communication while respecting confidentiality. Limits to the services should also be described, as not all adult mental health concerns can be addressed in a pediatric hospital setting, and those needing special treatment or treatment for serious mental illness (e.g., schizophrenia) should be referred out when clinically indicated.

Some pediatric psychologists may hesitate to move toward the integration of caregiver mental health services within the pediatric hospital setting. Evaluation and treatment of adult mental health disorders differ from those of children. The training background of pediatric psychologists varies with some coming from programs relevant to both children and adults while others trained on a more “child” oriented track. Thus, some providers may feel their expertise and experience treating adults is limited, leading to discomfort in this role. However, continuing education efforts and peer consultation could be used to mitigate some of these concerns. Second, most pediatric psychologists carry full caseloads with long waitlists of pediatric patients. Setting aside provider time devoted to caregivers’ needs may be a daunting task, particularly as the mental health of children continues to be a major public health concern (CDC 2022) and staffing remains limited. Thus, continuing effort to expand personnel, perhaps including adult-focused providers, is necessary.

A notable benefit of an integrated caregiver psychosocial treatment program is that it establishes a protocol for the creation of a caregiver chart for documentation, an option currently not available in many pediatric facilities. Similarly, this is not the norm in hospitals working with caregivers of adults who are seriously ill, although calls to create a chart for “adult” caregivers have been made (Applebaum et al. Reference Applebaum, Kent and Lichtenthal2021). Separate charts allow detailed documentation by the psychologist both for established treatment and for any emergent mental health contact with a caregiver not previously in treatment. For example, in the case of a mental health crisis such as suicidality, documenting in the caregiver’s own medical record will reduce liability and protect confidentiality. A separate chart also allows documentation for follow-up outreach and services for bereaved caregivers.

No widely recognized approach for integrating mental health treatment for caregivers within the child’s hospital setting exists, as the initiation of these programs is still in its infancy (Kahhan and Junger Reference Kahhan and Junger2021). However, some pediatric oncology psychosocial programs are offering assessment and mental health treatment to caregivers of children with cancer either in person (e.g., Kearney Reference Kearney2014; McTate et al. Reference McTate, Szulczewski and Joffe2021) or via telehealth (Elliott et al. Reference Elliott, Corneau-Dia and Turner2021). In these programs, the caregiver becomes an identified patient, which results in a separate electronic medical record permitting documentation and billing of the caregiver’s insurance. Within pediatric primary care, addressing caregivers’ needs can lend to the more comprehensive care of children and families (Maragakis et al. Reference Maragrakis, Ham and Bruni2021). One example of co-located care for caregivers in a pediatric setting is HealthySteps, a national program that screens for maternal depression and other family needs. Lessons from these programs can be beneficial to establishing an integrated model of addressing caregiver mental health in the pediatric hospital setting.

Regardless of the pathway chosen, legal and ethical challenges arise when addressing (or choosing not to address) a caregiver’s mental health care in the pediatric hospital setting.

Legal and ethical considerations

Legal considerations relevant to addressing caregiver mental health needs in the context of pediatric health care are emphasized here; however ethical aspects are also addressed because some states incorporate a version of the American Psychological Association Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (APA) into their state regulations (e.g., Tenn. Admin. Code § 1180-01-.09(1) and (2); Nev. Admin. Code § 641.250; Ga Comp. R. & Regs. 510-4-.02). Legal and APA Code citations are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. Many of the considerations addressed below have been discussed previously from the clinician’s perspective; now we take a closer look at these issues from a legal/ethical perspective. Some elements are similar to that described by Maragrakis et al. (Reference Maragrakis, Ham and Bruni2021) who discussed considerations focused primarily in pediatric primary care settings.

As noted previously, relevant to the first and third pathways for providing mental health care to caregivers within the pediatric medical context by dual treatment or by an integrated care model, programs must consider whether the available mental health providers have sufficient training, competence, and, where applicable, hospital privileges, to screen and address the needs of adults (APA § 2.01). Ubiquitous psychological caregiver screening may pose risks to the caregiver, the psychologist, and the hospital if screening discloses significant mental health issues without a clear pathway to help the caregiver.

Specifically, addressing caregiver mental health issues in tandem with the child’s mental health-care risks caregiver confusion about the role of the psychologist, even when the psychologist discloses the risks of the “multiple relationships” under APA §§ 3.05 and 3.07. As noted above, screening or tandem treatment, where caregiver-directed intervention is subsumed within the pediatric patient’s care, may inadvertently create a provider/patient relationship with the caregiver. The psychologist would then owe the same legal and ethical duties to the caregiver as to any other patient, including recognizing and disclosing the possibility of conflicting interests under APA § 3.05. The psychologist might be exposed to professional discipline, a malpractice suit, or other legal liability for alleged violations of these duties. Separate care that is integrated into the pediatric health-care delivery system may avoid some of these risks by directly establishing an acknowledged client relationship with the caregiver.

Among the duties in a psychologist/patient relationship are privacy and confidentiality. In various forms, these duties are imposed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations, state laws, and APA §§ 4.01, 4.02, 4.04, 4.05, and 6.02. Maintaining confidentiality when the caregiver is treated during the patient’s sessions (under the first pathway) is almost impossible, poses ethical and legal risks for the psychologists, and may curtail caregiver candor. Following the second pathway, a psychologist must still maintain a record of the referral to an outside provider, which will find a home either in the patient’s medical record or in a separate “shadow” file, discussed below, neither of which is ideal. The third pathway allows separate appointments, somewhat separate professional relationships, separate documentation, and separate billing – and all of these can be done while maintaining caregiver confidentiality.

Beyond the duty of confidentiality is a state-law legal privilege, found in some form in most or all states (e.g., Tenn. Code Ann. § 63-11-213; NY CPLR § 4507; TX Rules of Evidence, Rule 501; WI Stat. Annot. 905.04). Although the scope of the psychologist/patient privilege varies by state, generally speaking, the privilege may impose a further non-disclosure duty on the psychologist. However, if the privilege is challenged and the caregiver is not considered the client by the court, for example under the first pathway, where the client is the pediatric patient, the psychologist could be compelled to testify in legal proceedings about what the caregiver said, believing it was confidential. Consider a caregiver who discloses that they are in recovery from addiction, a fact not known to their partner, and which could be revealed in a legal proceeding in which the psychologist is called to testify, even if this is not charted in the patient’s medical record. This risk, too, is minimized when the caregiver is a separate patient of the psychologist, as the privilege would, by law, apply.

Another important legal duty of the psychologist is to maintain a record for each patient detailing diagnosis, treatment plan, test results, and outcomes. This duty arises under APA § 6.01, federal hospital regulations (42 CFR § 482.24), and state laws governing hospitals (e.g., Tenn. Admin. Code §1200.08.01-.06(5)(d); 10 NY Admin. Code 405.10) and psychologists (e.g., Tenn. Admin. Code § 1180.01-.06; 22 TX Admin. Code § 465.22). How and the extent to which this duty applies is unclear if the caregiver is not the identified patient because caregiver mental health issues are being addressed only under either the first or second pathway. Does discussion of the caregiver’s mental health issues create a psychologist/patient relationship that necessitates documentation? If so, and if there is not a separate chart for the caregiver, recording in the pediatric patient’s chart a caregiver’s personal history and presenting concerns can pose both legal and ethical issues. Charting about the caregiver in the patient’s medical record may breach caregiver confidentiality (APA § 4.01) and fail to minimize intrusions into privacy (APA § 4.04). A caregiver might reveal, for example, a history of childhood sex abuse by someone who is no longer alive and poses no threat to the pediatric patient or anyone else . This information placed in the pediatric patient’s record will be accessible to anyone else accessing the patient’s medical record for medical, administrative, legal, or other reasons. This may “out” the caregiver’s confidence and even make them available for use against the caregiver in custody or other court proceedings. Further, the caregiver’s charted confidences under the first pathway, or their referral for more intensive mental health care under the second pathway, will be visible to the patient upon emancipation or reaching the age of majority. A patient could then learn, for example, of the caregiver’s “secrets,” or that the patient’s illness prompted marital conflict.

To avoid charting in the patient’s record when the third pathway – a separate but integrated care model with the caregivers having their own charts – is not available, options that hospital psychologists may have used to protect caregiver confidentiality include: (1) Documenting caregiver information in “psychotherapy” notes under HIPAA (45 CFR §§ 164.501, 164.524(a)(1)(i), 164.524 (a)(2)(i)). These are notes anticipated to be used only by that one provider and may not meet the need to inform other providers of various disciplines of important information about the patient and family. (2) Using “shadow charts” to record certain information that needs to be recalled but not shared. This is strongly disfavored or prohibited at many institutions and also fails to inform other providers (Ley, Reference Ley2014). (3) Documenting in an oblique and non-informative fashion, only as relevant to the patient, giving as little detail as possible; this may not jog the provider’s memory when needed and also fails to inform other providers. 4) Documenting more completely but withholding the caregiver’s mental health information under HIPAA if the disclosure is reasonably likely to endanger the life or physical safety (45 CFR 164.524(a)(3)) – so long as withholding does not violate the relatively new Information Blocking Rule (45 CFR Part 171).

However, psychologists may need to document information related to a caregiver’s mental health more formally, even if only in the patient’s chart, for patient safety, to limit the psychologist’s own potential liability, and to inform themselves and other professionals in rendering future care. (APA § 6.01). For example, psychologists must document in the child’s record actions taken to protect the patient when the caregiver is impaired, such as arranging for another caregiver to transport and care for the patient. Similarly, if the caregiver indicates suicidal or homicidal ideation, a record must be maintained that shows the psychologist assessed and took appropriate action to refer the caregiver or warn a potential victim, even if the child’s record is the only place to chart this information. While this is an extreme (but not uncommon) example, it shows the need for integrated care allowing a separate caregiver chart. A separate psychologist/client relationship and a separate chart in the pediatric hospital will protect the caregiver’s confidentiality and privacy by keeping secrets out of the patient’s record and enable the psychologist to assert that the related communications are protected by the state-law psychologist/patient privilege. This approach also minimizes the risk of confusion on the part of the patient and caregiver as to who is the client and what is confidential and reduces the likelihood of the psychologist being held liable for inadvertently creating a client relationship where none is intended. It may also reduce the likelihood of liability for failing – in an effort to protect privacy – to adequately document the caregiver’s disclosures and the psychologists’ appropriate assessment and response. More forthright documentation can protect the psychologist, and inform other health-care providers of information they may need to know. At the same time, this approach enables the psychologist to gain a more robust understanding of and relationship with the family through discourse outside the hearing of the pediatric patient and to more fully support their various mental health needs.

As noted above, if the third pathway of an integrated but separate care model is adopted, an institution may be faced with the need to allocate this possibly scarce resource, as the available mental health providers may not have time to schedule separate appointments with all caregivers with these needs. Selecting those with the greatest barriers to access to outside care is one option, and requesting an ethics consult to assist with an algorithm to allocate the resource, as is sometimes done in the case of drug shortages, would be a responsible approach.

Conclusions

Evidenced-based interventions are available to treat mental health symptoms in adults. Common mental health concerns, which are also often of particular concern for caregivers of ill children, such as insomnia, depression, anxiety, and chronic stress can respond well to treatment with evidenced-based interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (Trauer et al. Reference Trauer, Qian and Doyle2015; van Dis et al. Reference van Dis, van Veen and Hagenaars2020), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Twohig and Levin Reference Twohig and Levin2017), and Mindfulness strategies (Goldberg et al. Reference Goldberg, Tucker and Greene2018). Additionally, interventions have been developed specifically to target needs of caregivers of children in some illness groups, most of which are adapted from already established evidenced-based treatments for mental health concerns (Law et al. Reference Law, Fisher and Eccleston2019). For example, Bright Ideas (Dolgin et al. Reference Dolgin, Devine and Tzur-Bitan2021) and PRISM-P (Rosenberg et al. Reference Rosenberg, Bradford and Junkins2019) have been developed to enhance functioning in caregivers of children with cancer. Mothers of infants have responded well to supportive psychotherapies delivered in the NICU (Hatters Friedman et al. Reference Hatters Friedman, Kessler and Nagle Yang2013). Family-focused interventions, such as those developed for families coping with pediatric chronic pain conditions, have also demonstrated a benefit to caregivers (Law et al. Reference Law, Fisher and Howard2017). However, despite the availability of these, and other, interventions pediatric psychologists and hospitals face challenges in determining the most suitable approach for care.

Consideration of available institutional and community resources, professional competencies, legal requirements, ethical guidelines, circumstances unique to the pediatric hospital setting, and clinical judgment are all necessary. Of the three most common pathways in the pediatric setting, the development of “fully integrated” programs, where caregivers are registered as patients with their own medical records, ensures caregivers receive access to needed care while also giving psychologists the best solution to satisfy their own legal, ethical, and professional duties. Separate, but integrated and informed psychological care of caregivers is likely to be the most beneficial and least risky for all parties.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951522001353.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this paper were presented at the 2021 Annual Society of Pediatric Psychology Conference (Virtual). Legal information and opinion are those of the author alone (K.S.) and are not attributed to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.