INTRODUCTION

The desire of the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and those in Eastern Europe to transform their economies into innovation economies has stimulated a push for entrepreneurship and experimentation with new business models. A business model is a holistic concept that ‘explains’ how firms create and capture value, (e.g., Volberda, Van Den Bosch, & Heij, Reference Volberda, Van den Bosch and Heij2018). It has been described at various levels of abstraction, ranging from a narrative to activity systems (Massa & Tucci, Reference Massa, Tucci, Dodgson, Gann and Philips2014). Hamel (Reference Hamel2000) has provided what is possibly the simplest definition, describing a business model as a ‘way of doing business’ or a ‘business concept’. Amit and Zott (Reference Amit and Zott2001: 493) give a more complicated definition. They describe a business model as a bundle of specific activities designed ‘to create value through the exploitation of business opportunities’ by highlighting ‘the content, structure and governance of transactions’.

In a way, the business model describes the structure of the value chain that is needed to create and distribute a value proposition, as well as the extra assets required for this process (Foss & Saebi, Reference Foss, Saebi, Foss and Saebi2015; Morris, Schindehutte, & Allen, Reference Morris, Schindehutte and Allen2005; Spieth, Schneckenberg, & Ricart, Reference Spieth, Schneckenberg and Ricart2014). The value proposition describes how value is realized for specific target groups and markets. For example, it can provide cost advantages, meet previously unmet needs with new products and services, offer greater information and choice, or confer status associated with a brand (Mitchell & Coles, Reference Mitchell and Coles2003; Osterwalder & Pigneur, Reference Osterwalder and Pigneur2009). A business model results in substantial added value if it makes new combinations possible, involves greater switching costs for customers (lock-in effects), creates a strong interdependency between activities, and delivers substantial cost savings as a result (Amit & Zott, Reference Amit and Zott2001).

Aided by idiosyncratic customer needs, increasing demand, and often less encumbered by an established infrastructure, the transforming economies have become a fascinating context for business model innovation, with incumbent firms adapting their business model or coming up with entirely new models. Similarly, start-up companies may invent new business models that challenge or leapfrog ‘tired’ old models. However, research that specifically explores business model innovation in transforming economies is still in its initial stages. Although we have witnessed a fast increase in research on business models over the past decade (cf. Foss & Saebi, Reference Foss and Saebi2017; Massa, Tucci, & Afuah, Reference Massa, Tucci and Afuah2017; Zott, Amit, & Massa, Reference Zott, Amit and Massa2011), the overwhelming majority of studies have focused on developed economies. A keyword search for ‘business model innovation’ in the titles, abstracts, and keywords of articles in the Management and Business categories on the Web of Science results in 468 articles, whereas restricting the location to transforming economies gives only 43 articles.Footnote [1] Figure 1 depicts the growing research interest for business model innovation and shows that research with a specific focus on transforming economies is lagging behind by some distance.

Figure 1. The growth of research on business model innovation (BMI)

This stark imbalance is both surprising and worrisome as the transforming economies are at the forefront of business model innovation. For instance, apps such as Alipay, created by Alibaba in China, have revolutionized online retailing and can be used for all types of transaction that are hindered by a lack of trust between the parties involved. Furthermore, business model innovation helps firms to compete successfully on the global stage, as shown, for example, by Huawei's emergence as the global leader in telecommunication networks and the decline of incumbents such as Lucent and Ericsson. This lack of scholarly attention to transforming economies as the context for business model innovation is limiting our understanding, since many of these innovations not only have important implications for the local communities but also create new global competitive dynamics as firms in those economies start to internationalize. To advance business model innovation research, it is of paramount importance to shift our attention to transforming economies.

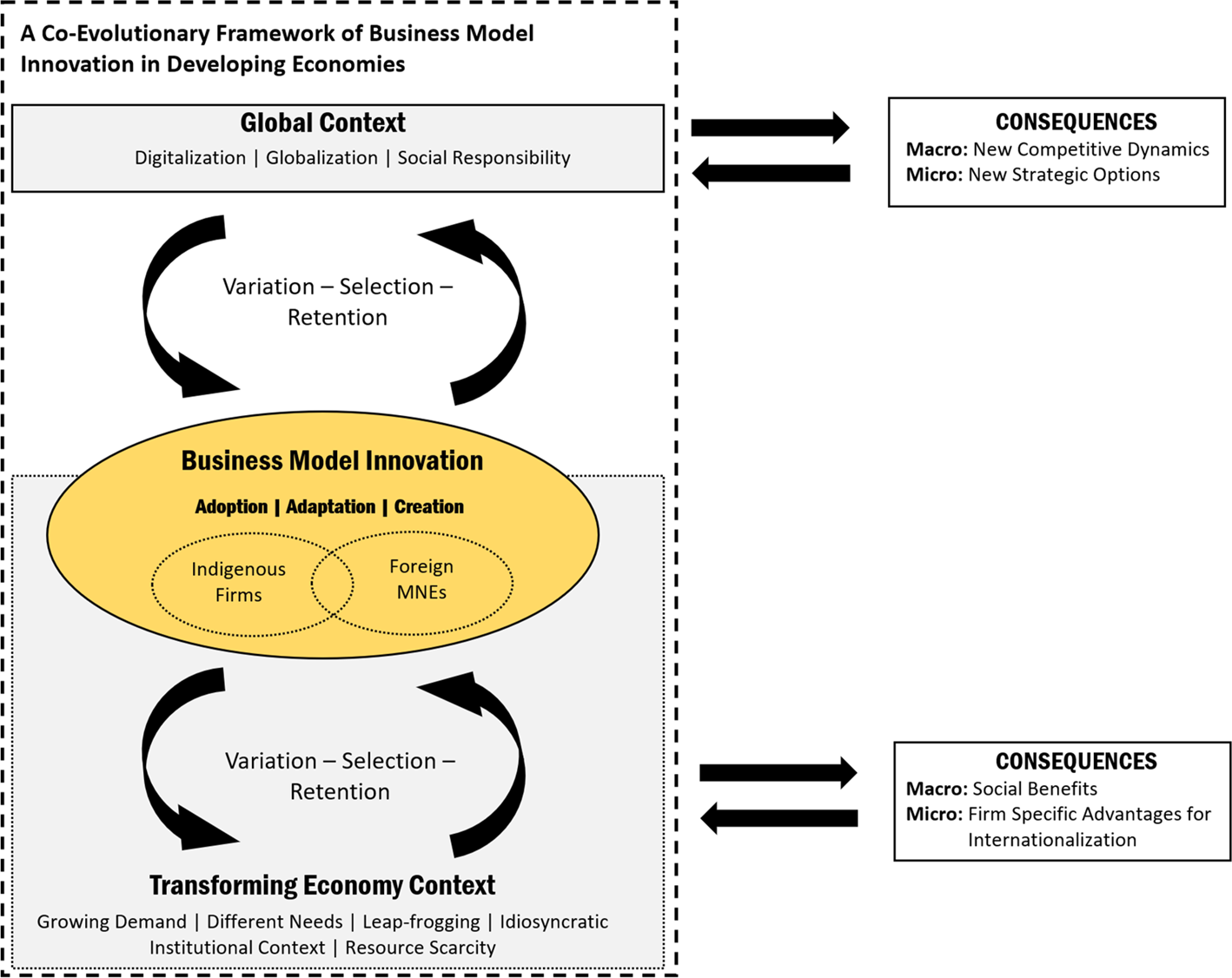

In this article, we develop a co-evolutionary framework of business model innovation in developing economies. Business model innovation in transforming economies refers to the process through which firms react to the idiosyncrasies of their local environment as nested within the global context to develop new ways of doing business, which not only improve the firms’ local and global competitiveness but also, because of their social and competitive implications, have the potential to alter the local and global environment. Specifically, our co-evolutionary framework proposes that business model innovation in transforming economies depends on the characteristics of the local environment and developments in the global environment. In turn, the new models developed in transforming economies shape the local environment though their influence on the social and economic aspects of the society and potentially affect competitive dynamics of the global context as they give organizations firm-specific advantages as they begin to compete outside of their national borders. These co-evolutionary dynamics rest on variation-selection-retention processes that take place both within and outside transforming economies.

We structure our discussion of the proposed co-evolutionary framework by considering which types of firms are most active in business model innovation in transforming economies (indigenous firms or MNEs) and what business model innovation involves in transforming economies (adoption, adaptation, or even creation). We also show how and why firms in transforming economies have begun to challenge the position of global industry leaders, despite not having their resource advantages, proprietary technology, or market power. We also show the consequences for the domestic and global environment. Figure 2 depicts our co-evolutionary framework of business model innovation in transforming economies.

Figure 2. The co-evolutionary framework of business model innovation in transforming economies

In addition, we highlight the main contributions of the articles in this special issue by considering their implications for the co-evolutionary perspective of business model innovation in transforming economies. The studies span a variety of topics including different types of business model innovation (adoption-adaptation-retention), those involved (indigenous firms and foreign multinationals), and the locations, motivations, and consequences. We also suggest various avenues for future research. These ideas are based both on what we see as current gaps in our understanding of the co-evolution of business models and transforming economies and on current developments in the global environment that are likely to influence business models in those economies.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, we develop a co-evolutionary framework of business model innovation in transforming economies. To this end, we synthesize insights from previous research that addresses relevant elements of our framework. Second, we highlight the main ideas of the seven contributions to the special issue, giving particular consideration to how they inform the co-evolutionary perspective. Lastly, we present avenues for future research.

A CO-EVOLUTIONARY FRAMEWORK OF BUSINESS MODEL INNOVATION IN TRANSFORMING ECONOMIES

Who Innovates the Business Model: Indigenous Firms vs. MNEs?

The transforming economies provide an important arena for experimentation for both indigenous firms and foreign multinationals, and each have their own advantages when it comes to developing new business models. Indigenous firms are particularly attuned to customer needs and are well positioned to tap into local resources. They can leverage their knowledge of the market and relationships with local stakeholders to introduce business models designed around a deep understanding of their potential customers and the country's context. Examples of indigenous business model innovation range from the food industry, including new ways of providing healthy food in the favelas (Colovic & Schruoffeneger, Reference Colovic and Schruoffeneger2021), to the high-tech applications that include platform firms (Su, Zhang, & Ma, Reference Su, Zhang and Ma2020), social media (e.g., Ma & Hu, Reference Ma and Hu2021), or mobile payments (Gnatzy & Moser, Reference Gnatzy and Moser2012).

In contrast, foreign MNEs can devise new ways of creating and capturing value by experimenting with novel combinations of firm-specific advantages and the transforming economy's particular context. For instance, in an analysis of 15 international retailers doing business in China, Cao, Navare, and Jin (Reference Cao, Navare and Jin2018) argue that business model innovation can be undertaken by exploiting the firm's home-based resources and making changes to fit the local market by making changes to the target client, shopper value, or value chain. Similarly, Landau, Karna, and Sailer (Reference Landau, Karna and Sailer2016) describe how a German luxury automobile manufacturer adapted its business model in India, using a phased process in which it paid differing degrees of attention at various points to value proposition, value creation and delivery, and value capture. However, while the transforming economies might provide opportunities for business model innovation, MNEs, being embedded in multiple contexts, need to develop capabilities that enable them to overcome the challenges of managing multiple business models (Demir & Angwin, Reference Demir and Angwin2021). Thus, both indigenous and foreign MNEs can take advantage of the vibrant environment of transforming economies to engage in business model innovation, even though they may be doing so in different ways.

What Form of Business Model Innovation is Being Used in Transforming Economies: Adoption, Adaptation, or Creation?

Business model innovation refers to new ways of creating and capturing value. Depending on the degree and type of newness, there can be three types of business model innovation in transforming economies. The first is adoption, which is when firms implement new ways of creating and capturing value but simply copy these from other firms, either in developed or transforming economies, and use off-the-shelf solutions (i.e., without significant modification). In this literal geographical replication, an existing business model is applied in a different country or region (Baden-Fuller & Winter, Reference Baden-Fuller and Winter2007; Dunford, Palmer, & Benveniste, Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010; Volberda et al., Reference Volberda, Van Den Bosch and Mihalache2014).

The second type is adaptation, when firms also copy a business model from another firm but make significant changes to it to leverage their own resources and competencies more effectively or to create a fit with the environment in which they are operating (Volberda et al., Reference Volberda, Van Den Bosch and Mihalache2014). Business model adaptation by indigenous firms is not about cloning the original model but creating a model that is broadly similar (Baden-Fuller & Winter, Reference Baden-Fuller and Winter2007). The focus is on improving existing methods of value creation and appropriation by making incremental changes to an existing model that has proven successful elsewhere (e.g., Baden-Fuller & Winter, Reference Baden-Fuller and Winter2007; Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, Reference Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart2011). Adaptation involves reconstructing a system of activities and processes that are often imperfectly understood, causally ambiguous, complex, and interdependent (Szulanski & Jensen, Reference Szulanski and Jensen2008; Winter & Szulanski, Reference Winter and Szulanski2001). It is a dynamic and evolving process (Dunford et al., Reference Dunford, Palmer and Benveniste2010) that requires the right balance between learning, change, and precise replication (Winter, Szulanski, Ringov, & Jensen, Reference Winter, Szulanski, Ringov and Jensen2012). The more proficiently a firm replicates a business model in another setting, the more effectively it can reap the rewards of that adaptation (Volberda et al., Reference Volberda, Van den Bosch and Heij2018).

Studies on the adoption and adaptation of business models overwhelmingly look at how firms from transforming economies adopt and adapt business models from developed nations. An example discussed in this issue (Mehrotra & Velamuri, Reference Mehrotra and Velamuri2021) is the business model innovation of Goli Vada Pav Private Limited (GVPPL), an Indian fast-food restaurant that adapted the McDonalds franchise model in a way that enabled it to create new ways of identifying and engaging with customers that were appropriate for the Indian market while imitating the value chain setup – they even used the same supplier as McDonalds.

The third type of business model innovation is the creation of new models in-house that are sufficiently different from existing ones to be classed as new to the industry or to the world. Business model creation can be defined as the introduction of new business model components or new interdependencies between those various components that go beyond the framework of an existing model in order to create and capture new value (e.g., Morris et al., Reference Morris, Schindehutte and Allen2005). It involves radically appraising a firm's current business model (e.g., Amit & Zott, Reference Amit and Zott2001; Eyring, Johnson, & Nair, Reference Eyring, Johnson and Nair2011) in order to arrive at a new or more sustainable competitive position for the firm (Giesen, Riddleberger, Christner, & Bell, Reference Giesen, Riddleberger, Christner and Bell2010; Markides & Oyon, Reference Markides and Oyon2010). There are two key steps in business model creation. First, a firm obtains new business model components (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Schindehutte and Allen2005), either by developing them itself (making), acquiring them (buying), or accessing external components (e.g., by making alliances). Next, it creates new interdependencies between those components (e.g., Johnson, Christensen, & Kagermann, Reference Johnson, Christensen and Kagermann2008; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Schindehutte and Allen2005). This is done either by fundamentally revising the existing model (Cavalcante, Kesting, & Ulhøi, Reference Cavalcante, Kesting and Ulhøi2011) or by developing an entirely new model (e.g., Govindarajan & Trimble, Reference Govindarajan and Trimble2011). For instance, Meyer (Reference Meyer2017) describes a business model developed by the Haier Group, a Chinese multinational in the home appliances and consumer electronics industry, in which the company leveraged its strong reach into rural China to create value by renting out its distribution and service channels to foreign competitors. Another example featured in this issue (Ma & Hu, Reference Ma and Hu2021) is ByteDance's development of a unique business model with TikTok; this model creates value by combining elements of social networking and video-sharing platforms with a proprietary artificial intelligence algorithm and experiments with novel ways of capturing value such as advertisements, in-app purchases, and collaborations with various brands.

As all three types of business model innovation – adoption, adaptation, and creation – are a manifestation of the interaction between firms and the environment, to understand more about business model innovation in transforming economies we need to understand how firms introduce new ways of creating and capturing value and why environmental factors and managerial intentionality drive this process. Although the conventional view taken by scholars is that indigenous firms typically use imitation, where the main goal is total reproduction of a product, strategy, trait, or behavior in order to mimic global industry leaders, what we are arguing with our co-evolutionary perspective on business model innovation in transforming economies is that firms in transforming economies use a mixture of adoption, adaptation, and creation.

How and Why Can Resource-Constrained Firms in Transforming Economies Develop New Business Models?

We put forward a co-evolutionary model of business model innovation in transforming economies. Co-evolutionary theory, which forms the basis for our perspective on business model innovation in transforming economies, holds that firms and the macro-environment affect one another over time (Volberda & Lewin, Reference Volberda and Lewin2003). That is, the environment shapes business model innovation as it affects opportunities and resources available due to idiosyncrasies in customer and institutional factors. In turn, through their business model innovation firms shape the environment, because the models used affect the firms’ competitiveness, create social value, and alter institutions. This mutual influence develops over time, as the dynamics between business model innovation and the environment of transforming economies are formed gradually and in different areas.

We develop our co-evolutionary model of business model innovation in transforming economies based on the processes of variation, selection, and retention and discuss how these processes are influenced by and influence the environment. Variation in business models arises as a response to particular needs in the market. Consequently, business model innovation depends on the one hand on environmental characteristics and, on the other, on firms’ ability to identify opportunities and act on them.

Variation – Environmental drivers

In transforming economies, the environment plays a particularly prominent role in stimulating business model innovation. Since the transforming economies are growing rapidly and striving to become innovation economies, firms are encountering changing customer needs and increasing purchasing power, new technologies, volatile regulatory systems, and varied government support programs. As studies have shown, these conditions provide ample opportunities for business model innovation.

Indigenous firms are particularly well positioned to identify these opportunities. For instance, Colovic and Schruoffeneger (Reference Colovic and Schruoffeneger2021) describe the rising need for and increasing customer openness to healthier food alternatives in Brazil's favelas (i.e., poor neighborhoods). They show how a restaurant chain developed a business model to address this need using a creative business model that involved local stakeholders. In another study of business model innovation in Brazil, Sousa-Zomer and Cauchick-Miguel (Reference Sousa-Zomer and Cauchick-Miguel2019) argue that successful implementation of business models that move away from the concept of ownership (e.g., bike-sharing or renting water purification systems) depends on social factors including people's attitudes towards ownership, administrative programs for lowering carbon emissions, and technological factors for connecting with customers. Research also shows that, in India, it was the combination of advances in mobile payment technologies and regulatory support from government and NGOs that created the conditions for business model innovation in the health insurance industry (Gnatzy & Moser, Reference Gnatzy and Moser2012). In addition, in countries where people have low income, customer needs for inclusive healthcare form the basis for business model innovation in that sector (Angeli & Jaiswal, Reference Angeli and Jaiswal2016).

Idiosyncratic costumer needs and institutional characteristics are important also when discussing business model innovation by foreign MNEs doing business in transforming economies. For instance, Oyedele (Reference Oyedele2016) argues that market conditions in transforming economies, such as the power of non-governmental institutions, clientelism (i.e., the exchange of goods and services in return for political support), and informal institutional flux shape the cost structures and revenue streams: MNEs might therefore need to change their value proposition accordingly. MNEs may also need to change their business model when doing business in emerging markets in order to gain legitimacy as there may be different regulative, normative, and cognitive legitimacy needs associated with different regulatory bodies, customers, and partners (Wu, Zhao, & Zhou, Reference Wu, Zhao and Zhou2019).

Interaction between the global and local environment can also stimulate business model innovation. A case in point is the relationship between the growing shift from our current linear economy to a circular economy, where the focus is on reducing consumption and reusing or recycling items or materials. In India, which produces three million truckloads of solid waste each day there are great opportunities for business model innovation based on the principles of a circular economy (Goyal, Esposito, & Kapoor, Reference Goyal, Esposito and Kapoor2018).

Variation – Firm drivers

While the environment creates problems and opportunities that can stimulate business model innovation, the next question that arises is why some firms engage in business model innovation and not others, even though they all operate in the same environment. Since firms have their own particular characteristics and resources, there are significant differences in how they identify and tackle problems and opportunities that lead to new business models.

Research points to several firm characteristics that are important in stimulating business model innovation. One of these is exploratory orientation; in a sample of Chinese firms Guo, Su, and Ahlstrom (Reference Guo, Su and Ahlstrom2016) find that this type of orientation increases a firm's ability to recognize opportunities and to engage in entrepreneurial bricolage. An even stronger finding, in a study of Chinese platform enterprises, is that entrepreneurial orientation is a necessary condition for business model innovation (Su et al., Reference Su, Zhang and Ma2020). Likewise, firms’ market orientation is also important for business model innovation. Yang, Wei, Shi, and Zhao (Reference Yang, Wei, Shi and Zhao2020) find that, for Chinese firms, both responsive and proactive market orientation stimulate business model innovation, but their effect depends on how flexible firms are in coordinating their resources; flexibility strengthens the effect of responsive market orientation but weakens the effect of proactive orientation. In addition, entrepreneurial alertness also can stimulate business model innovation, because it enhances explorative and exploitative learning (Zhao, Yang, Hughes, & Li, Reference Zhao, Yang, Hughes and Li2020).

Research also highlights several organizational capabilities that allow firms to spot and act on opportunities that help them to develop and implement new business models. Two important capabilities are agility in capitalizing markets, which is related to monitoring and responding quickly to customer needs (Liao, Liu, & Ma, Reference Liao, Liu and Ma2019), and integrative capability, which helps business model innovation as it allows firms to combine information and resources from inside and outside the organization (Pang, Wang, Li, & Duan, Reference Pang, Wang, Li and Duan2019). In addition to capabilities, studies also indicate that firms’ resources are important for business model innovation. Firms’ networks with customers, financial investors, and collaborators are particularly important in this regard, as they play a key role not only in developing new business models but also in implementing them successfully (Liu & Bell, Reference Liu and Bell2019).

In addition, in a study of the introduction of a microcredit platform in China, Zhang, Daim, and Zhang (Reference Zhang, Daim and Zhang2018) argue that the firm's IT infrastructure was a key factor in its business model innovation, allowing it to connect customer needs with other internal resources and to provide flexibility in how it delivered value to consumers. Similarly, Wu, Guo, and Shi (Reference Wu, Guo and Shi2013) argue that, for IT-based business model innovation, the IT system is a key resource, because it contributes to value delivery by providing better access to knowledge for both firms and customers; it also enables firms to capture value as it reduces the costs of increasing revenue streams. Also, research on a sample of Eastern European firms shows that technological innovation is positively related to business model innovation, since firms may experiment with new business models to get maximum value from new products (Smajlovi, Umihanic, & Turulja, Reference Smajlović, Umihanic and Turulja2019).

Variation – Managerial drivers

Variation in business models also arises because of differences in managers’ characteristics and behaviors. For instance, studies have found that the Big Five personality traits of the top managers affect the extent to which firms engage in business model innovation: Extroversion, agreeableness, and openness have a positive effect on business model innovation, whereas neuroticism has an adverse effect (Anwar, Shah, Khan, & Khattak, Reference Anwar, Shah, Khan and Khattak2019). Also, important for business model innovation are top managers’ managerial skills, which help them coordinate and configure resources, entrepreneurial skills such as alertness, which help them sense and seize opportunities, and professional ties, which allow them not only to collect information from clients and suppliers but also to redefine the value network (Guo, Zhao, & Tang, Reference Guo, Zhao and Tang2013). Similarly, the boundary-spanning behavior of top management teams can stimulate business model innovation as it leads to increased bricolage (Yan, Hu, Liu, Ru, & Wu, Reference Yan, Hu, Liu, Ru and Wu2020).

Selection

Business model innovation is no guarantee of success. That is, not all new models will survive. In other words, variation is followed by selection. Models that are not appropriate for the transforming economy will not perform well and unless they are transformed in some way to address deficiencies in performance, they will fall out of use. Whereas variation is born out of perceived needs in the environment, selection processes test the appropriateness of firms’ responses to those needs.

Research on the selection of business models in transforming economies attempts to identify what factors make business more likely to lead to improved performance. These factors range from strategic choices to firm resources or the characteristics of the managers concerned. A particularly important strategic choice for the success of a new business model is when it is deployed and what environmental conditions are like at that point. Chen, Zang, Chen, He, and Chieh (Reference Chen, Zang, Chen, He and Chieh2020) identify four areas that firms could consider when deciding on the timing: governmental strategic priorities, customer characteristics, technological sophistication, and industrial opportunities. Also, in terms of strategic factors, the strategy employed by these firms seems to be key. Supporting this idea, Pang et al. (Reference Pang, Wang, Li and Duan2019) find in their sample of Chinese firms that while a differentiation strategy enhances the positive effect of business model innovation on firm performance, a cost leadership strategy has the opposite effect. Another important factor could be the developmental stage of the firm itself; Wang and Zhou (Reference Wang and Zhou2020) find that business model innovation may enhance the performance of social enterprises as it can increase their legitimacy, but this effect is more positive in the early stages of growth.

Characteristics of the top management teams can also affect the performance of new business models. Distinguishing between efficiency-centered and novelty-centered business models, Guo, Pang, and Li (Reference Guo, Pang and Li2018) find that the functional diversity of the top management team can enhance the link between novelty-centered models and firm performance, and that diversity in tenure enhances the link between efficiency-centered models and firm performance.

Importantly firms from transforming economies go through a business model selection process for not only for their domestic market but also for overseas markets, as business model innovation is also required for internationalization. Although some research acknowledges the importance of business model innovation for the internationalization performance of firms from transforming economies (Jean & Tan, Reference Jean and Tan2019), more in-depth study of the selection process for the global stage, particularly given the rapid increase in the internationalization of firms from transforming economies, is now needed. Thus, the firm–environment dynamics at the selection stage provide some indication of the appropriateness of business model variants.

Retention

At this stage, successful business models will diffuse within the economy as other firms try to adopt and adapt those models that appear to be working well. Central to the diffusion process is human agency: entrepreneurs, managers, and business consultants identify business models variations that they deem to be promising and attempt to adopt and adapt them. It is important to acknowledge the direction of diffusion and the boundaries – or rather the lack of boundaries – for diffusion. That is, diffusion can take place within the transforming economy; it can be outside-in when business models are identified outside of the transforming economy (predominantly from developed economies), and conversely it can be inside-out when new models from within the transforming economy spread to other countries.

Most existing research shows how business models spread from developed to transforming economies. This process is driven both by MNEs who attempt to compete in transforming economies by transferring their existing models to them (e.g., Cao et al., Reference Cao, Navare and Jin2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Zhao and Zhou2019) and by indigenous firms who look abroad for new business model ideas (e.g., Mehrotra & Velamuri, Reference Mehrotra and Velamuri2021). An example of this type of business model diffusion is that of food delivery platforms from firms such as GrubHub, JustEat, or Takeaway.com in developed economies to firms in transforming economies (e.g., hipMenu in Romania).

Less well-studied is the reverse direction of diffusion: business models created in the transforming economies spreading to other transforming economies or to developed economies. In this issue, Ma and Hu (Reference Ma and Hu2021) highlight the importance of this type of diffusion by discussing TikTok's business model developed by the Chinese technology company ByteDance. As TikTok expanded and became successful outside of China, its business model spread to other countries as firms tried to emulate its success. One example is the Chingari app launched in India to provide similar functions to TikTok after TikTok was banned from operating there. TikTok's business model also spread to developed economies such as the US, where Instagram developed the Reels app based on the TikTok model.

Thus, the dynamics of the variation-selection-retention processes highlight the intricate relationships between indigenous and foreign firms and between the transforming economy environment and the global environment.

Consequences for the Domestic and Global Environment

Business model innovation in transforming economies has implications for both the domestic and the global environment. First, it can change the competitive dynamics in the domestic environment. This happens because business model innovation can lead to improved business performance (e.g., Queiroz et al., Reference Queiroz, Mendes, Silva, Ganga, Miguel and Oliveira2020; Smajlovi et al., Reference Smajlović, Umihanic and Turulja2019; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ma and Shi2010) and to new ways of interacting with customers, suppliers, and local institutions.

Second, business model innovation affects the environment of the transforming economy as it can create social value by providing needed services and addressing institutional voids. For instance, Velamuri, Anant, and Kumar (Reference Velamuri, Anant, Kumar, Baden-Fuller and Mangematin2015) show that the business model innovation (particularly changes in customer identification and engagement and in the value chain and monetization) that allowed two Indian hospitals both to gain financial benefits and to provide social value is likely to change the way that healthcare is delivered in India because it shows new ways of achieving seemingly contradictory goals: doing well and doing good. Also, as Colovic and Schruoffeneger (Reference Colovic and Schruoffeneger2021) demonstrate, business model innovation can create social value by driving institutional change. They show how the innovative business model of a new salad-based, fast-food business changed societal attitudes towards healthy eating and led to the development of local business networks by providing meaningful employment in disadvantaged areas. In their analysis of three cases in India, Hossain, Levänen, and Wierenga (Reference Hossain, Levänen and Wierenga2021) highlight how frugal innovation (i.e., innovation under serious resource-constraints) can help to improve various aspects of transforming economies, including social conditions (by providing access to basic services, improving participation), economic conditions (by creating new jobs, providing affordable products), and environmental conditions (by using local resources, lowering pollution) aspects of the transforming economies. Furthermore, Goyal et al. (Reference Goyal, Esposito and Kapoor2018) argue that business model innovation that is based on the principles of a circular economy could help improve sustainability in India by promoting the reduce, reuse, and recycle paradigm.

In addition, business model innovation can also have implications far beyond the borders of the transforming economy in which it originated as it can affect global competitive dynamics. One leading example of this is TikTok's business model (Ma & Hu, Reference Ma and Hu2021). While above we explained how this business model led to a new category of apps as Western developers started to adopt it, its influence on the global environment reaches beyond the digital realm, also changing the competitive dynamics in the retail sector. This is evident in Walmart's expressed intent to invest in TikTok and to develop a close relationship that would allow the mostly bricks-and-mortar retailer to gain a competitive advantage in the retail sector by using TikTok as a market research tool, as a new way to engage with consumers, and as a new channel through which to sell its products (Repko & Palmer, Reference Repko and Palmer2020). Thus, business model innovation has implications for the global environment. As transforming economies develop further towards innovation economies, there are likely to be more examples of business model innovation from these economies that alter the competitive dynamics on the global stage.

Overall, our co-evolutionary framework of business model innovation in transforming economies shows the interrelations not only between indigenous firms and the economy in which they are based but also between those firms and foreign MNEs, between the local and global contexts, and between indigenous firms and the global context.

ARTICLES IN THIS SPECIAL ISSUE

This special issue aims to highlight the transforming economies as hotbeds of innovation and, at the same time, to show how they are a key context for business model innovation that should be considered in future research. The seven contributions in this special issue advance our understanding of business model innovations in transforming economies by covering topics ranging from how business model innovation happens to its various consequences. These studies also relate to the different areas of the co-evolutionary framework we put forward in this study. Table 1 outlines the specific contributions of each study. Below, we introduce each one and emphasize its main contributions.

Table 1. Studies in this special issue

Mehrotra and Velamuri (Reference Mehrotra and Velamuri2021) advance our understanding of the drivers of business model innovation in transforming economies. Analyzing two quick service restaurant chains – one from China with over 1,400 outlets and one from India with over 300 outlets – they describe the process of business model innovation in transforming economies as one that involves taking elements from business models that have proven successful in developed markets and combining them with other elements created specifically to fit the particular needs of transforming economies. That is, they decompose business model innovation into imitative and creative elements. They refer to this process of replicating business models through inter-organizational learning as secondary business model innovation (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ma and Shi2010). Their study also reveals the mechanisms that drive the development of these business model elements. While the imitative elements result from a vicarious learning process comprising inspiration, observation, study, hiring talent from successful foreign organizations, and partnering with vendors of international brands, the creative elements result from contextual learning, involving opportunity recognition through cultural participation and learning through immersion in the industry. Thus, by providing insights into how firms from transforming economies conduct their business model innovation, this study contributes to the variation stage of our co-evolutionary model.

Ngoasong, Wang, Amdam, and Bjarnar (Reference Ngoasong, Wang, Amdam and Bjarnar2021) focus on how MNEs engage in business model innovation in transforming economies. As the transforming economies have particular characteristics, MNEs may often have to innovate their business model in order to compete in these markets. Examining a Norwegian maritime multinational with operations in China, the study shows that the differences between the business model employed in the transforming economy and the one used at home create structural tensions (e.g., how activities are organized globally), behavioral tensions (e.g., between HQ and subsidiary managers), and cultural tensions (e.g., the guanxi network). Furthermore, the study spotlights the subsidiary managers as being central to resolving the business model's integration/local responsiveness dilemma. It suggests that these managers can help to integrate the transforming economies into the MNE's global production network by engaging in market sensing and knowledge transfer activities and can help to solve behavioral and cultural tensions through relationship management. Thus, the study makes important contributions to understanding how MNEs can manage organizational tensions to allow business model innovation to take place in transforming economies.

Demir and Angwin (Reference Demir and Angwin2021) put forward the concept of ‘multidexterity’, which refers to ‘the ability to develop, nurture, and execute several distinctive BM strategies simultaneously across different levels and functions of the MNC and its host markets’. They develop this concept based on a case study of a European healthcare firm entering China, a firm that also has operations in other parts of the world. The study suggests that there are two main approaches that MNEs can use for managing multiple business models developed for the transforming economies alongside their global business model: loose vs. tight coupling and strong vs. weak coherence. Importantly, which approach might prove most effective depends on the characteristics of the transforming economy, including the ambiguity of its regulatory frameworks and industry standards as well as its rules for foreign ownership of local assets. Thus, the study advances research on the drivers of business model innovation in transforming economies by showcasing different strategies that MNEs can employ to manage multiple business models developed for countries with different conditions.

Wu, An, Zhen, and Zhang (Reference Wu, An, Zhen and Zhang2021) advance understanding of the consequences of business model innovation by considering which configurations of business model design are associated with higher levels of firm growth. Interestingly, the study specifically acknowledges the interdependencies between managerial decisions and the characteristics of the transforming economy environment in driving the performance of a particular business model. That is, a configurational approach is used to uncover which combinations of firm factors (i.e., state vs. private ownership, the development stage of the firm), business model design factors (i.e., novelty-centered, efficiency-centered), and environmental volatility are associated with higher levels of firm growth. To this end, the study analyzes data from 277 Chinese firms. Thus, it adds to our understanding of the selection process for business models in transforming economies as it shows when particular business model designs are more likely to contribute to firm growth.

Colovic and Schruoffeneger (Reference Colovic and Schruoffeneger2021) present a case study of a new salad-based fast-food restaurant chain in Brazil's favelas (i.e., disadvantaged neighborhoods) that employs an innovative business model. The study makes at least two important contributions. First, it details how this business model provides new ways of identifying customers, customer engagement, value chain linkages, and monetization by creating close links with deprived communities, for example, by engaging suppliers from the local favelas and offering affordable prices. Second, it addresses two important benefits of business model innovation: (i) addressing the institutional void by improving market functioning in deprived communities and enabling market participation by marginalized or socially excluded groups and (ii) creating social value in several ways by promoting social inclusion, improving the image of a stigmatized community, and establishing links between people from disadvantaged areas and other social groups. Overall, this study contributes to the co-evolutionary framework of business model innovation in transforming economies by highlighting the characteristics of such innovation and showing how it shapes the local environment.

Hossain, Levänen, and Wierenga (Reference Hossain, Levänen and Wierenga2021) highlight the social benefits of frugal innovation. They consider three Indian ventures that introduced products based on this type of innovation: a fridge made of clay aimed at consumers without access to electricity, a milking machine for small-scale farmers, and sanitary pads manufactured by local women in remote areas. The study maps the social, environmental, and economic improvements associated with frugal innovation. In many cases, firms in transforming economies have few resources at their disposal. This study emphasizes the far-reaching potential of business model innovation to provide benefits even in dire situations.

Ma and Hu (Reference Ma and Hu2021) showcase ByteDance's business model innovation in developing the TikTok mobile app, which quickly became one of the most downloaded and widely used apps globally. Their description of this business model innovation is particularly interesting as it exemplifies how a new business model can be created by crossing categories: TikTok is a hybrid of social networking and video-sharing. By combining aspects of these two technologies and adding a proprietary artificial intelligence algorithm, ByteDance developed new ways of creating and capturing value with TikTok. Importantly, the case highlights how the success of this business model is also due to the characteristics of the environment; ByteDance benefitted from China's increasingly strong IT infrastructure as well as from its large and ever more demanding home market. The TikTok case also shows the potentially far-reaching implications of business model innovation from transforming economies for global competitive dynamics, as the home market provides opportunities for experimenting with new ways of creating and capturing value that can provide competitive advantages when internationalizing.

Overall, the studies in this special issue make important contributions to advancing a co-evolutionary perspective of business model innovation in transforming economies. They show that environmental characteristics may offer different opportunities for business model innovation, illustrate how firms can capitalize on them, and indicate the consequences for the local and global environment.

FUTURE RESEARCH

While it has already been recognized in previous studies that the characteristics of transforming economies require firms to use different business models to those found in established economies, much work remains to be done to expand and deepen our understanding of new indigenous business model applications. More studies are needed to demonstrate new ways in which startups and incumbent organizations can cope with the universal limitations of bounded rationality, and to investigate how and why the new business models are successful in these transforming economies. Factors to consider include the history of these economies, the institutional configurations in force, the cultural philosophical roots, and specific notions such as the role of trust. How can indigenous firms, which may lack some important core competencies, devise new business models that can outcompete models from better resourced and more powerful rivals from advanced economies? Indigenous firms in transforming economies are able to identify a set of resources available in the market that they can purchase and combine them in a way to create new business models that are adaptable to market requirements (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015). They are able to creatively combine elements of successful Western business models and add new elements in such a way that they can develop extended offerings (e.g., new product functions, a superior consumer experience, and total business solutions), rapid market responses, and superior price–value ratios that are particularly well suited to local markets. Underpinning this variation in business models by local firms in transforming economies is managerial intentionality, manifested in market intelligence, organizational resilience, creative use of imitation, and entrepreneurial capabilities (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015: 380). Future research on business model innovation in transforming economies should explore the various managerial drivers involved.

Another critical area for more research is the development process and the micro-foundations of new business models in transforming economies. Of course, firm-level factors such as leadership, extreme philosophical beliefs, (e.g., Lewin, Välikangas, & Chen, Reference Lewin, Välikangas and Chen2017; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016), and organizational culture (e.g., Morris et al., Reference Morris, Schindehutte and Allen2005) can and do account for business model innovation. However, a much more nuanced understanding is needed of the various influences at different levels of analysis and the possible interplay between them (Ngoasong et al., Reference Ngoasong, Wang, Amdam and Bjarnar2021). The micro-coevolution of subsidiary managers’ market sensing and knowledge transfer in response to local market demands and institutional selection forces may create tensions with the macro-coevolution of plans at headquarters to replicate and refine well-proven global business models to exploit global market needs. As transforming economies move further up the added value chain, the institutional and technological environments are undergoing a transition, making it especially important to elucidate the co-evolution of firms’ business models innovation and national competitiveness. For instance, the growth and widespread use of the Internet and advances in virtual software applications such as block chain applications (Lansit & Lakani, Reference Lansist and Lakani2017) have given rise to new business models, new app-based services, and new ways of organizing work. Similarly, cloud applications and the gig economy are changing how companies organize work, where it is executed, and by whom (e.g., Kaganer, Carmel, Hirschheim, & Olsen, Reference Kaganer, Carmel, Hirschheim and Olsen2013; Malone, Laubacher, & Scot Morton, Reference Malone, Laubacher and Scott Morton2003).

More work is also needed to determine how business model innovation affects the competitiveness of firms from transforming economies. Similarly, it is important to develop a much more nuanced understanding of how the relationship between a new business model and the rapid change in transforming economies allows firms to implement and leverage new ways of doing business. Also, as these firms increasingly venture outside their national borders (Ramamurti, Reference Ramamurti2012), there is an urgent need to develop deeper insights into the socio-political and economic context and why and how their business models allow them to compete with multinationals from established markets that are often better resourced and have more international experience (Luo & Child, Reference Luo and Child2015). Biocon, for instance, an Indian pharmaceutical company, has a mission of making drugs and medicine affordable to all, with a business model that seeks to reduce disparities in access to safe, high-quality medicines as well as to address the gaps in scientific research in order to find solutions that would affect a billion lives (McKinsey, 2020). Biocon's ‘Mission 10 cents’ offers human insulin to diabetes patients in lower- and middle-income countries for less than ten cents a day. Biocon's range of products also includes oncology and immunology treatments available in more than 120 countries. The business models of firms in transforming economies have tended to be focused very much on scale, size, and market share, while the Western model is to capture as much value as possible through innovation and intellectual property and to outsource other activities. Of course, there is also an opportunity for business models devised in transforming economies to innovate and mimic some elements of successful Western business models. In this way transforming economies can move up the value chain and get the best of both worlds: a value-twin track of the traditional model (based on scale, size, and market share) on the one hand, and the innovative, high-value model, on the other.

Creatively combining elements from indigenous business models with elements from successful global businesses allows firms from transforming economies to create unique value. These firms can leverage their domestic base to experiment with new business model features, which can then be used for internationalization (Hutzschenreuter, Pedersen, & Volberda, Reference Hutzschenreuter, Pedersen and Volberda2007). Internationalization is the result of both management intentionality and experience-based learning. In other words, managers and entrepreneurs in transforming economies are assumed to have the ability and intention to influence what route a firm takes in its internationalization. Where the internationalization trajectories of these firms are based on new business models, they cannot be interpreted as incremental learning journeys as was suggested in Johanson and Vahlne's (Reference Johanson and Vahlne1977) well-known internationalization process model.

So far the international business literature has paid far more attention to the incremental, gradual, experience- and knowledge-based aspects of internationalization and to business model replication undertaken by Western firms. For instance, IKEA and McDonalds continually opened new branches on different continents (Johnsson & Foss, Reference Jonsson and Foss2011), and their enriched knowledge of operations, products, services, and markets, gathered over time, enabled them to refine their business models (Volberda et al., Reference Volberda, Van den Bosch and Heij2018). That is, MNEs that are pursuing global integration generally replicate their existing business models in transforming economies, making only incremental evolutionary changes in response to local market demands, local institutional settings, and regional regulatory requirements. However, the uncertain and volatile nature of transforming economies requires MNEs to experiment with fundamentally new business models while simultaneously exploiting their existing global business models (Demir & Angwin, Reference Demir and Angwin2021).

Unilever, for instance, had to experiment with fundamentally new business models in the homecare category to meet some of the demands of low-income buyers in India. How far should a giant company go to understand poor customers in faraway markets? How does such a company manage to sell its product profitably to hundreds of millions of people, dispersed and isolated, with hardly any disposable income? Unilever's global business model was based on selling high-price, high-profit brands to middle-class customers. Hindustan Lever, a subsidiary of Unilever and the largest consumer goods company in India, has embraced a different business model. It sells everything from soups to soaps by going wherever its customers are, whether that is the weekly cattle market or the well where the village women wash their clothes. Unilever recognizes that meeting the demands of poor consumers is not just about lowering prices but is also about creativity and experimenting with multiple business models – and in the end developing products and processes that do more with less. This implies that MNEs entering transforming economies should experiment with multiple business models while simultaneously exploiting their existing models. However, we need more research on how, in their internationalization strategies, MNEs can meet the unique requirements of transforming economies, which differ both from their global business model and from the unique local business models for other specific markets. The study by Demir and Angwin (Reference Demir and Angwin2021) showed various ways in which MNEs can develop and combine competing business models in transforming economies, depending on the degree of ambiguity in the regulatory frameworks and industry standards. The concept of multidexterity seems to be an appealing one, as it would enable MNEs to deploy multiple conflicting business models during market entry, but we definitely need more empirical research on internationalization of this kind.

Finally, most studies on paths to internationalization and business model innovation are written from the standpoint of MNEs from developed economies and examine the underlying factors that enable them to exploit or adapt their business models successfully when entering transforming economies. In this special issue, we make a plea for more fine-grained research on how indigenous firms in transforming economies can refine, extend, and upscale their business models and internationalize successfully when entering other transforming economies as well as developed economies. We seriously doubt whether existing theories on evolutionary internationalization, based mainly on Western MNEs, are likely to hold for the internationalization of firms with innovative business models from transforming economies. For this special issue we have therefore developed a co-evolutionary framework of business model innovation in transforming economies. Moreover, the role of managerial intentionality, and how it affects the business model innovation of firms in transforming economies, is still largely unexplored. To create new business models, firms in these economies engage in cross-industry imitation, using various elements from iconic business models from more advanced economies. However, they also make local adaptations and add new components to the business model (Mehrotra & Velamuri, Reference Mehrotra and Velamuri2021). More work is needed to understand what role managerial intentionality, together with the local selection environment, plays in achieving business model innovation in transforming economies. The articles in this special issue clearly show that transforming economies can provide a good arena for new business models.