MZ twins have long been assumed to be genetically identical, which is an important assumption for twin studies, where phenotypic correlations between MZ twins and dizygotic twins are compared in order to estimate the relative contribution of genes and environment in human traits (Boomsma et al., Reference Boomsma, Busjahn and Peltonen2002). MZ twins are, in fact, genetically identical at conception, but can accumulate mutations after the zygote splits, making MZ twins informative for the study of somatic mutations. Post-twinning point mutations have been reported (Kondo et al., Reference Kondo, Schutte, Richardson, Bjork, Knight, Watanabe and Murray2002; Reumers et al., Reference Reumers, Rijk, Zhao, Liekens, Smeets, Cleary and Del-Favero2012; Sakuntabhai et al., Reference Sakuntabhai, Ruiz-Perez, Carter, Jacobsen, Burge, Monk and Hovnanian1999; Vadlamudi et al., Reference Vadlamudi, Dibbens, Lawrence, Iona, McMahon, Murrell and Berkovic2010; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Beekman, Lameijer, Zhang, Moed, van den Akker and Slagboom2013), but are expected to be scarcer than post-twinning de novo CNVs. CNVs, the most studied type of structural variant, are segments of DNA ranging from 1 kb to several Mb that differ in copy number (CN) across different members of the species. CNVs have a higher mutation rate than single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and affect larger segments of the genome (Itsara et al., Reference Itsara, Wu, Smith, Nickerson, Romieu, London and Eichler2010; Lupski, Reference Lupski2007; van Ommen, Reference van Ommen2005). Even though post-twinning de novo CNVs are expected to be rare, they can potentially aid in finding causal variants for genomic disorders. After Bruder et al. (Reference Bruder, Piotrowski, Gijsbers, Andersson, Erickson, Diaz de Ståhl and Poplawski2008) demonstrated the existence of CNV discordance in MZ twins, many studies followed that tried to find CNV discordances that might be explanatory for phenotypic MZ discordances.

Table 1 shows an overview of studies attempting to detect CNV differences between MZ twins since 2008. Forsberg et al. (Reference Forsberg, Rasi, Razzaghian, Pakalapati, Waite, Thilbeault and Dumanski2012) conducted the largest study of this kind to date, examining 159 MZ pairs, and validated five post-twinning mutations >1 Mb and five <1 Mb, all found in the older twin pairs of their sample (>60 years old). An estimate of the post-twinning mutation rate for CNVs is difficult to make with this design, since it is likely to depend on the age of the twins, with older individuals having an increased chance for somatic mutations (Forsberg et al., Reference Forsberg, Rasi, Razzaghian, Pakalapati, Waite, Thilbeault and Dumanski2012; Ye et al., Reference Ye, Beekman, Lameijer, Zhang, Moed, van den Akker and Slagboom2013), and likely also depends on tissue (Piotrowski et al., Reference Piotrowski, Bruder, Andersson, de Stahl, Menzel, Sandgren and Dumanski2008). The majority of studies looking for CNV discordances in MZ twins did not detect reproducible post-twinning CNV mutations, indicating that relatively large CNV discordances between MZ twins are a considerably rare phenomenon, or are at least hard to detect, even among phenotypically discordant twins.

TABLE 1 List of Studies Searching for Post-Twinning De Novo CNVs

Most studies on post-twinning de novo CNVs first scan the entire genome using genome-wide microarray technology, making them only sensitive for relatively large CNVs (>10–100 kb), and then validate suggestive signals with additional and more sensitive molecular assays, such as qPCR. In practice, CNVs have been considered relatively noisy when using currently available genome-wide microarray technologies, and qPCR has shown to be effective in validating CNV signals from microarray data (Weaver et al., Reference Weaver, Dube, Mir, Qin, Sun, Ramakrishnan and Livak2010; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Qian, Akula, Alliey-Rodriguez, Tang, Gershon and Liu2011).

We conducted a genome-wide scan for post-twinning de novo CNVs (>100 kb) in 1,097 unselected MZ twin pairs with a wide age range (0–79 years old). DNA was extracted from blood for about half of the samples, which included the majority of adult subjects >18 years old, and the other half of the samples (mainly children) had their DNA extracted from buccal swabs (see Figure 1). CNVs are measured with the Affymetrix 6.0 microarray, and after stringent Quality Control (QC), a selection of post-twinning de novo CNV candidates is made for qPCR replication. Phenotypic data based on extensive longitudinal questionnaires (Boomsma et al., Reference Boomsma, Geus, Vink, Stubbe, Distel, Hottenga and Bartels2006) were available to be examined for twin pairs with validated post-twinning mutations. In addition, we examined the concordance rates of CNV calls within MZ twin pairs and compared those between the different sources of DNA. Finally, we selected CNVs concordant within MZ pairs to conduct gene-enrichment tests in order to test whether CNV events impacting gene sets involved in neuronal processes are associated with TP or AP. The TP and AP scales measure heritable constructs (Abdellaoui et al., Reference Abdellaoui, Bartels, Hudziak, Rizzu, Van Beijsterveldt and Boomsma2008; Reference Abdellaoui, de Moor, Geels, van Beek, Willemsen and Boomsma2012; Derks et al., Reference Derks, Hudziak, Boomsma and Kim2009) that are predictive for schizophrenia (Kasius et al., Reference Kasius, Ferdinand, Berg and Verhulst1997; Morgan & Cauce, Reference Morgan and Cauce1999) and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Derks et al., Reference Derks, Hudziak, Dolan, Ferdinand and Boomsma2006) respectively, for which CNVs have been shown to be a risk factor (Cook Jr., & Scherer, Reference Cook and Scherer2008; Stefansson et al., Reference Stefansson, Meyer-Lindenberg, Steinberg, Magnusdottir, Morgen, Arnarsdottir and Doyle2014; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Zaharieva, Martin, Langley, Mantripragada and Gudmundsson2010).

FIGURE 1 Age distribution of twins per tissue type for all samples (above) and the 152 putative de novo CNVs (below).

Methods

Participants

The 1,097 MZ twin pairs included in this study were registered with the Netherlands Twin Registry (NTR) (van Beijsterveldt et al., Reference van Beijsterveldt, Groen-Blokhuis, Hottenga, Franić, Hudziak, Lamb and Schutte2013, Willemsen et al., Reference Willemsen, Vink, Abdellaoui, Braber, van Beek, Draisma and van Lien2013), and were not selected based on phenotypic information. SNPs from the Affymetrix 6.0 microarray confirmed that all twins were indeed MZ. The mean age of the twins was 25.04 (SD = 15.86), and ranged from 0 to 79 years old (see Figure 1). DNA was extracted from blood for 1,163 twins (mean age = 35.53, SD = 13.24), and from buccal epithelium for 1,031 twins (mean age = 13.11, SD = 8.39). There were 566 pairs in which both twins had their DNA extracted from blood, 500 pairs in which both twins had their DNA extracted from buccal epithelium, and 31 pairs where one had DNA from blood and the other from buccal epithelium. Methods for buccal and blood collection and genomic DNA extraction have been described previously (Willemsen et al., Reference Willemsen, De Geus, Bartels, Van Beijsterveldt, Brooks, Estourgie-van Burk and Kluft2010).

CNV Calling

Data from 1,097 MZ twin pairs were extracted from a dataset containing a total of 13,188 samples that were genotyped on the Affymetrix Human Genome-Wide SNP 6.0 Array according to the manufacturer's protocol. This array contains 906,600 SNP and 940,000 CN probes. Of the CN probes, 800,000 are evenly spaced across the genome and the rest across 3,700 known CNV regions. SNPs were called using Affymetrix Powertool, and were used during the QC stage and to confirm the zygosity of MZ twins. CNVs were called with the Birdsuite (Korn et al., Reference Korn, Kuruvilla, McCarroll, Wysoker, Nemesh, Cawley and Darvishi2008) and PennCNV (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Hadley, Lium, Glessner, Grant and Bucan2007) algorithms.

For Birdsuite 1.5.5, the Affymetrix Powertool (APT-1.10.2, plug-in to Birdsuite 1.5.5) was used for plate-wise normalization. This algorithm searches for consistent evidence for CNVs across multiple neighboring probes. Information from neighboring probes is integrated into a CN call (0, 1, 2, 3 or 4) for the segment covered by the probes using a hidden Markov model (HMM)-based algorithm. A logarithm of the odds ratio (LOD)-score was generated for each CNV segment, indicating the likelihood of a CNV relative to no CNV in the region. CNV segments were only included if they had a LOD-score >10. We followed the recommendation from the manual in creating batches (http://www.broadinstitute.org/science/programs/medical-and-population-genetics/birdsuite/birdsuite-faq), and processed a maximum of 96 samples per batch. If the plate of origin was known, samples from the same plate were included in the same batch, resulting in 178 batches. Samples where the plate of origin was not known (~3%) were randomly distributed across five batches.

PennCNV was used to call genotypes, extract allele-specific signal intensities, cluster canonical genotypes, and finally generate a standard input file including log-R ratio (LRR) values and the ‘B allele’ frequency (BAF) for each marker in each individual. PennCNV uses a HMM-based approach for kilobase-resolution detection of CNVs. We followed the recommendation from the manual in creating batches (http://www.openbioinformatics.org/penncnv/penncnv_tutorial_affy_gw6.html), and processed as many samples per calling batch as possible, resulting in four batches (one batch including all twins and duplicates with N = 4,182, and three batches with N = 3,002 per batch).

The CN calls of Birdsuite and PennCNV were compared with a script written in Perl. CN segments were only included in further analyses if the following conditions were met: (1) the CN calls agreed between both algorithms, (2) the overlapping part of the segments from both algorithms was >100 kb, and (3) the segment was not in a centromere. Calls were also included if the CN call in Birdsuite was equal to the expected CN (CN = 2) and the segment was not present in the PennCNV output, since PennCNV only gives the CN state when the CN deviates from the expected CN, and Birdsuite gives CN states for all segments. Since calling algorithms can produce artificially split CNV calls, adjacent CNV calls were merged after manual inspection of LRR and BAF plots, if the gap in between was ≤50% of the entire length of the newly merged CNV.

Individuals were excluded from CNV calling if they had: (1) contrast QC < 0.4 (CQC, a quality metric from Affymetrix representing how well allele intensities separate into clusters); (2) SNP missingness > 10%; (3) had excess genome-wide heterozygosity/inbreeding levels (F, as calculated in PLINK (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Neale, Todd-Brown, Thomas, Ferreira, Bender and Daly2007) on an LD-pruned set, must be greater than -0.10 and smaller than 0.10); (4) if they had >50 CNVs with CN ≠ 2. After QC, 12,559 samples remain with a mean CQC of 2.17 (datasets are considered problematic if the mean CQC is smaller than 1.70).

Identifying Putative Post-Twinning De Novo CNVs

CN calls of complete MZ twin pairs passing QC (N = 1,097, mean CQC = 2.25) were analyzed to detect possible post-twinning de novo CNV events. Segments with CN differences between MZ twins were extracted with a purpose written Perl script, which compares segments with the same start and end positions between twins, as well as overlapping segments.

As an additional quality control, LRR and BAF plots were created for the putative de novo CNV segments and were visually inspected by AA and EE. CNVs with LRR and BAF plots that showed the strongest discordance were chosen for qPCR validation candidates.

qPCR Validation for Putative Post-Twinning De Novo CNVs

Calibrator sample selection

We selected a sample with CN = 2 in the regions included in the qPCR experiments as a calibrator sample, which was used to calibrate the qPCR assay to what a signal from CN = 2 should look like. Calibrator samples were selected using Affymetrix 6.0 and next generation sequence data from the partially overlapping NTR-GoNL (Boomsma et al., Reference Boomsma, Wijmenga, Slagboom, Swertz, Karssen, Abdellaoui and van Dijk2014) database (total overlap between the NTR-Affymetrix 6 and GoNL dataset = 81 samples). For these 81 individuals, we first selected samples that showed CN = 2 in Birdsuite and no call from PennCNV in the candidate regions. From this set, we then selected samples that showed no CN calls in the GoNL sequence data for two CNV calling algorithms, CNVnator (Abyzov et al., Reference Abyzov, Urban, Snyder and Gerstein2011) and DWAC-seq (http://tools.genomes.nl/dwac-seq.html), since these algorithms, like PennCNV, only make calls when CN ≠ 2. After visual inspection of the LRR & BAF plots for the remaining samples, we then selected one calibrator sample with CN = 2 for the qPCR experiments.

CNV Confirmation by qPCR

Samples identified as possible carriers of post-twinning de novo CNVs (N = 20 MZ pairs) were removed from -20˚C storage at the Avera Institute for Human Genetics, quantitated using Qubit 2.0 Broad Range Assay (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and normalized to 5ng/μl. Proposed CNVs were validated using qPCR. Four TaqMan Copy Number Assays (see Table 3) were run on a Viia7 real-time PCR machine (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). TaqMan Copy Number Reference Assay RNase P (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was used as an internal reference because it is known to exist in two copies in a diploid genome. The copy number assay reporter was FAM and the RNase P reference assay reporter was VIC. All four assays were performed on genomic DNA and run in 384 well PCR plates, with individual reaction volumes of 10 μl. Each sample was run with four replicates for accuracy. The four assay plates each contained the respective CNV candidates along with one non-template control sample and one calibrator sample (CN = 2). Using ViiA7 Software v1.2, the Ct threshold was set to manual with a value of 0.2 and auto-baseline was selected to ‘ON’. PCR conditions included an initial hold at 95°C for 10 min, and then 95°C for 15 s followed by 60°C for 1 min, together repeated for 40 cycles.

TABLE 2 CNV Calls from Affymetrix 6.0 and qPCR Experiments for 20 Putative De Novo CNVs

TABLE 3 TaqMan Copy Number Assay Names and Chromosome Locations

Data generated from the four CNV assays were analyzed with CopyCaller Software v2.0 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Ct values from both the copy number assay and the reference assay were exported as (.txt) files to CopyCaller. Analysis settings incorporated a calibrator sample with CN = 2. Comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) relative quantitation analysis was performed and sample copy numbers were called using the software algorithm. The ΔΔCt analysis method first determines the difference in Ct value (ΔCt) between the target regions and the reference assay, then it determines the difference between those ΔCt values and the calibrator sample (ΔΔCt). With this information, the CopyCaller Software generates both a calculated and a predicted CN value.

Statistical Analyses

CNV discordance within MZ pairs

Pearson correlations of LOD-scores between co-twins and Pearson correlations of the number of probes between co-twins were computed in IBM SPSS Statistics 21. A chi-squared test was conducted in order to test whether the putative de novo CNVs were associated with the source of DNA. The difference in age between samples that showed a putative de novo CNV and the rest of the samples was tested with a t test for blood and buccal epithelium separately.

CNV concordance within MZ pairs

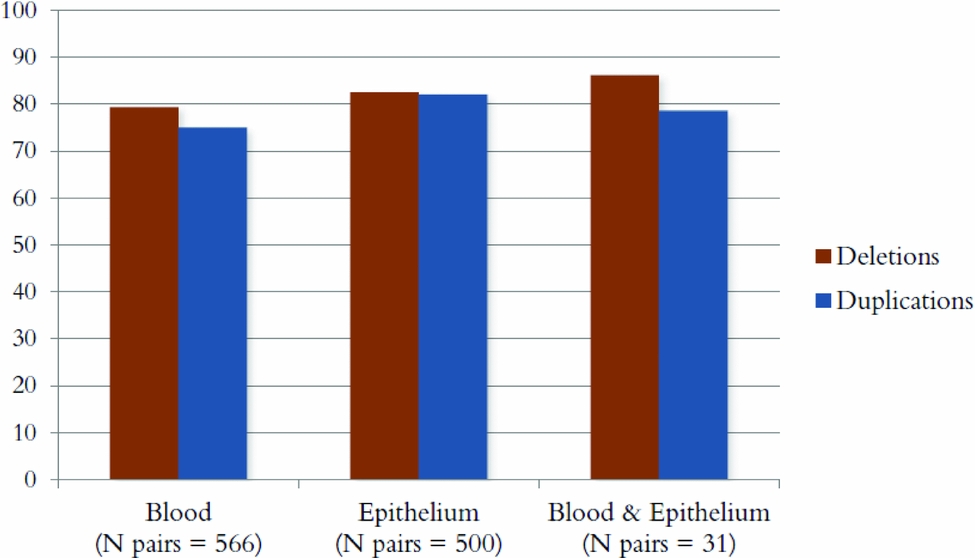

We performed chi-squared tests in IBM SPSS Statistics 21 to test whether CNV calls with CN ≠ 2 were equally concordant within MZ pairs for three groups of twin pairs: twins pairs with DNA from blood, twin pairs with DNA from epithelium, and twin pairs were one twin had DNA from blood and the other from epithelium. A CNV was regarded as concordant if the overlap between MZ pairs was > 100 kb. A total of 4,415 deletions and 3,037 duplications were included in these analyses. It was also tested whether the total number of concordant CNVs with CN ≠ 2 per twin pair differed between these three groups of twin pairs with a one-way ANOVA.

Concordant CNVs versus psychiatric symptoms

A gene-enrichment test was performed in PLINK (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Neale, Todd-Brown, Thomas, Ferreira, Bender and Daly2007, Raychaudhuri et al., Reference Raychaudhuri, Korn, McCarroll, Altshuler, Sklar, Purcell and Consortium2010) in order to test whether CNV events impacting gene sets involved in neuronal processes were associated with TP or AP. TP and AP were measured longitudinally with the adult self-report questionnaires (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2003), which is part of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment. The maximum TP and AP scores over four measurement time points was used for the gene-enrichment analyses. We randomly selected one twin per MZ pair, unless one twin had a missing phenotype, in which case the twin with the non-missing phenotype was selected (TP N = 674, AP N = 461). The gene sets involved in neuronal processes were downloaded from the Molecular Signature Database, and were derived from the GO Biological Process Ontology (http://www.geneontology.org/GO.process.guidelines.shtml), and included genes involved in the generation of neurons (83 genes), neuron development (61 genes), neuronal differentiation (76 genes), and neuron apoptosis (17 genes).

Results

CNV Discordance within MZ Pairs

There were 556 CNV segments that showed a CN discordance between MZ twins >100 kb. The LOD-scores from the Birdsuite calls (a quality metric indicating the likelihood of a CNV relative to no CNV in the region) showed a significant negative correlation within twin pairs (r = -0.247, p = 3.5 × 10−9), as did the number of probes encompassing the CNV (r = -0.248, p = 3.1 × 10−9), indicating systematic quality differences in CNV calls within twin pairs. More than 70% of these calls (N = 400) showed an overlap of <10% between twins from the same twin pair (note that the overlap was >100 kb). This indicates that many CN discordances may be caused by inaccurate CNV breakpoint estimates and/or a quality difference in CN calls. After only including CNVs with an overlap between twins of >10%, 153 putative de novo CNVs >100 kb remained, of which the correlations of the LOD-scores and number of probes between co-twins were no longer significant (r = -0.029, p = .724, and r = -0.036, p = .654, respectively). Of these 153 CNVs, more than half (N = 90; 58.8%) were from chromosome 15q11.2, ranging from bp positions 18,466,953 to 20,776,822 (build 36). LRR and BAF plots were generated for both twins for all 153 CNVs. These LRR and BAF plots were inspected manually in order to select putative de novo CNVs suited for qPCR replication. Twenty CNVs were chosen based on discordance in the LRR&BAF plots (inspected by AA and EE), of which 19 were in chromosome 15q11.2, and were followed up with qPCR validation experiments.

Two CNVs in the same twin pair showed a CNV discordance in the qPCR experiments for two CNVs in 15q11.2 (~350 kb in 18,491,920–18,841,578, and ~280 kb in 19,090,388–19,369,260; see Table 2 and Figure 2). The twin pair was 13 years old at the time of sampling, and their DNA was extracted from a buccal epithelium sample. They do not show large phenotypic differences with respect to overall health, behavior, (birth) length, (birth) weight, or other physical appearance in longitudinal parental and self-report questionnaires from age 1 to 21. The twin with CN = 3 for both CNVs (twin 2 in Table 2 and Figure 2) did perform better in school and finished high school two levels higher than the twin with CN = 1 and CN = 2, consistent with their CITO (http://www.cito.nl/) score difference (10 points higher for twin 2). Of the remaining 18 non-replicated de novo CNVs, 17 were due to a failure to detect a CNV with CN ≠ 2 in one of the twins (Table 2).

FIGURE 2 Log-R Ratio (LRR) for CNV probes & B allele frequency (BAF) for SNP probes of the two validated post-twinning mutations in the same 13-year-old twin pair (see Table 1 for bp positions and more details on the qPCR results for a and b, respectively). LRR is shown in vertical bars and BAF in solid points. The LRR & BAF values are shown in color in the region of the post-twinning de novo CNV (red and blue, respectively), and in black in the flanking regions.

The remaining 133 putative de novo CNVs were not independent from the source of DNA, χ2(2) = 7.91, p = .019. Post-hoc tests showed that this was due to de novo CNVs being found significantly more often in DNA from blood than in DNA from buccal epithelium; 65.5% had blood-derived DNA; χ2 (1) = 7.77, p = .005. As nearly all young twins were done on buccal epithelium, and adult samples in blood, we checked whether the age difference might have contributed to the overrepresentation of blood-derived samples. For both blood and buccal epithelium samples, samples with a putative de novo CNV showed a higher average age than the rest of the samples from the same source without a putative de novo CNV (38.63 vs. 35.70 for blood; 14.84 vs. 12.67 for buccal epithelium samples), but these differences were not significant (p = .119 and p = .294 respectively).

CNV Concordance within MZ Pairs

Figure 3 shows the percentage of CNVs that were concordant between MZ pairs for deletions and duplications for each source of DNA. The percentages were ~80% for all three groups: DNA from blood for both twins, epithelium for both twins, and one twin from blood and one from epithelium. A one-way ANOVA showed that the small differences in concordance rates between different sources of DNA were significant; deletions: χ2(2) = 8.69, p = .013; duplications: χ2(2) = 20.24, p = 4 × 10−5. Post-hoc tests showed these differences to be significant between blood and buccal epithelium-derived samples only (deletions: p = .012; duplications: p = 7 × 10−6), with buccal epithelium-derived samples showing a slightly higher concordance rate. Note that there were very few twin pairs where one twin had his/her DNA extracted from blood and the other from epithelium (N = 31 pairs), which likely makes a comparison between this group and the other two groups underpowered.

FIGURE 3 The percentage of CNVs that was concordant within MZ pairs for three groups: DNA from blood for both twins, epithelium for both twins, and one twin from blood and one from epithelium.

There was also a significant difference between the different sources in the total number of concordant CNVs per twin, F(1, 1,094) = 7.24, p = .001. A post-hoc test showed that this was due to blood-derived samples showing significantly more CNVs per twin (mean = 2.88, SD = 1.74) than epithelium-derived samples (mean = 2.48, SD = 2.01; p = .001). Twin pairs discordant for source of DNA showed 3.19 CNVs per twin on average (SD = 1.76). The difference in the total number of concordant CNVs between sources was also significant when analyzing deletions and duplications separately; deletions: F(2, 1,094) = 4.21, p = .015; duplications: F(2, 1,094) = 5.04, p = .007.

Concordant CNVs versus Psychiatric Symptoms

CNVs that were concordant within MZ pairs were tested for association with AP (ADHD symptoms) and TP (schizo-obsessive symptoms) using the gene-enrichment test in PLINK (Purcell et al., Reference Purcell, Neale, Todd-Brown, Thomas, Ferreira, Bender and Daly2007, Raychaudhuri et al., Reference Raychaudhuri, Korn, McCarroll, Altshuler, Sklar, Purcell and Consortium2010). The enrichment was tested for all genes, and gene-sets involved in generation of neurons (83 genes), neuron development (61 genes), neuronal differentiation (76 genes), and neuron apoptosis (17 genes).

The only significant association was observed between AP and the gene set involved in neuronal apoptosis (p = 4×10−39). This association disappeared after permutations. Permutations (10 k) were performed within four clusters based on gender and source of DNA.

Discussion

We searched for post-twinning de novo CNV mutations >100 kb in ~1,100 unselected MZ twin pairs using the Affymetrix 6.0 microarray. CNVs were called using two algorithms, which resulted in 153 putative de novo CNVs, of which the majority came from the 15q11.2 region. Twenty candidates, of which 19 were from 15q11.2, were selected for qPCR replication based on visual inspection of 153 LRR and BAF plots. Two were validated, suggesting the remaining 133 putative de novo mutations also likely contain a substantial proportion of false positives. The large majority of non-replicated de novo CNVs (17 out of 18) are due to a failure to detect a CNV with CN ≠ 2 in one of the twins (Table 2). The significant overrepresentation of blood-derived samples among the remaining 133 putative somatic mutations may be explained by quality differences between blood- and buccal epithelium-derived samples, but may also partly be explained by true mutations that increase with age, as (1) blood-derived samples were predominantly adult as opposed to buccal-derived samples, (2) carriers of putative de novo CNVs from both blood and buccal epithelium showed a higher average age than the rest of the samples from the same tissue (although non-significant), and (3) previous studies have shown that de novo mutations increase with age (Forsberg et al., Reference Forsberg, Rasi, Razzaghian, Pakalapati, Waite, Thilbeault and Dumanski2012, Kong et al., Reference Kong, Frigge, Masson, Besenbacher, Sulem, Magnusson and Jonasdottir2012, Ye et al., Reference Ye, Beekman, Lameijer, Zhang, Moed, van den Akker and Slagboom2013).

Two post-twinning CNVs in 15q11.2 were replicated in a young MZ twin pair that showed no large phenotypic differences. CNVs in 15q11.2 have been associated with Prader–Willi and Angelman syndromes (Donlon, Reference Donlon1988), schizophrenia (Stefansson et al., Reference Stefansson, Rujescu, Cichon, Pietiläinen, Ingason, Steinberg and Buizer-Voskamp2008), behavioral disturbances (Doornbos et al., Reference Doornbos, Sikkema-Raddatz, Ruijvenkamp, Dijkhuizen, Bijlsma, Gijsbers and Kerstjens-Frederikse2009), developmental and language delay (Burnside et al., Reference Burnside, Pasion, Mikhail, Carroll, Robin, Youngs and Papenhausen2011), epilepsy (de Kovel et al., Reference de Kovel, Trucks, Helbig, Mefford, Baker, Leu and Ostertag2010), and more recently with decreased fecundity, dyslexia, dyscalculia, and brain structure changes that are associated with schizophrenia and dyslexia (Stefansson et al., Reference Stefansson, Meyer-Lindenberg, Steinberg, Magnusdottir, Morgen, Arnarsdottir and Doyle2014). The 15q11.2 region is one of the genomic regions rich in segmental duplications (Zody et al., Reference Zody, Garber, Sharpe, Young, Rowen, O’Neill and Cuomo2006), which makes CNVs in these regions harder to detect and therefore more likely to contain false positives, but also means this region is enriched for CNVs and more prone to de novo CNV mutations through non-allelic homologous recombination (Redon et al., Reference Redon, Ishikawa, Fitch, Feuk, Perry, Andrews and Chen2006).

MZ twins provide the opportunity for an extra QC step for the relatively noisy microarray CNV data. About 80% of CNV calls were concordant between MZ pairs. It was difficult to judge which source of DNA is more suitable for CNV detection, as buccal epithelium-derived DNA showed a significantly higher concordance rate between MZ pairs, but blood-derived DNA allowed us to pick up significantly more concordant CNVs per twin pair. It was clear, however, that it is important to account for the source of DNA in association analyses, as a highly significant association between AP and CNVs affecting genes involved in neuronal apoptosis disappeared after accounting for source of DNA. Besides a relatively small sample size, another reason for not replicating associations with psychiatric symptoms may be false negative CNV calls in one of the twins. Since nearly all discordant CNVs that were included in the qPCR experiments (17 out of 18, excluding the replicated de novo CNVs) showed either a deletion or duplication in both twins, it is likely that a substantial part of the CNVs that showed a discordance within the MZ pairs reflect true CNV events (i.e., events with CN ≠ 2) that were missed by the CNV calling algorithm(s) in one of the twins. In other words, even though the confidence level of CNV calls is increased when only including concordant (i.e., replicated) CNVs, it may also result in missing true CNV calls.

In short, this study confirms the importance of qPCR replication when attempting to detect large post-twinning de novo CNVs and shows the importance of accounting for the source of DNA in studies using microarray CNV data. It is not clear yet why the 15q11.2 region is over-represented among CNVs discordant within twin pairs, since these may also reflect true post-twinning de novo CNVs. Association studies may also benefit from qPCR validation and genetic duplicates, as the large majority of discordant CNVs that were followed up with qPCR validation experiments turned out to be deletions or duplications that were concordant within MZ twin pairs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the twins and family members for their participation. This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO: MagW/ZonMW grants 904-61-090, 985-10–002,904-61-193,480-04-004, 400-05-717, Addiction-31160008 Middelgroot-911-09-032, Spinozapremie 56-464-4192, Geestkracht program grant 10-000-1002), Center for Medical Systems Biology (CMSB, NWO Genomics), NBIC/BioAssist/RK(2008.024), Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (BBMRI–NL, 184.021.007), the VU University's Institute for Health and Care Research (EMGO+) and Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam (NCA), the European Science Foundation (ESF, EU/QLRT-2001–01254), the European Community's Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013), ENGAGE (HEALTH-F4–2007–201413); the European Science Council (ERC Advanced, 230,374), Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository (NIMH U24 MH068457–06), the Avera Institute for Human Genetics, Sioux Falls, South Dakota (USA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH, R01D0042157–01A). Part of the genotyping was funded by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN) of the Foundation for the US National Institutes of Health (NIMH, MH081802) and by the Grand Opportunity grants 1RC2MH089951–01 and 1RC2 MH089995–01 from the NIMH. AA was supported by CSMB (http://www.cmsb.nl/). Part of the analyses was carried out on the Genetic Cluster Computer (http://www.geneticcluster.org), which is financially supported by the Netherlands Scientific Organization (NWO 480-05-003), the Dutch Brain Foundation, and the Department of Psychology and Education of the VU University Amsterdam.