To the Editor—Switzerland is one of the few countries where routine postdischarge surveillance (PDS) for the surveillance of surgical site infections (SSIs) is practiced by telephone interview 1 month (and for implanted devices a second interview at 12 months) after the procedure, which is comparable with the system in the Netherlands.Reference Manniën, Wille, Snoeren and van den Hof 1

This survey was designed to analyze the perceptions on work load and value of PDS by Swiss infection control practitioners in order to assess the efficiency of resource utilization. The online questionnaire was distributed in December 2015 and January 2016. A major limitation of the study is the subjective assessment method of the survey, but the high response rate of 76 (62.3%) of the 122 Swiss hospitals that were asked to participate provides a representative sample.

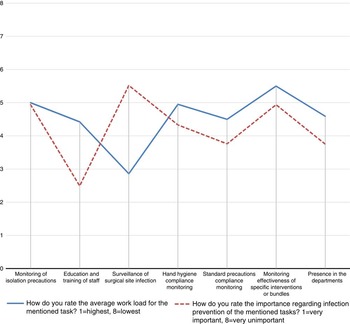

Although the practical value of PDS related to clinical infection control is rated moderate on an 8-item Likert scale, the work load is rated high compared with other duties (Figure 1). A total of 23 (37.1%) of the 62 respondents for this item say that they definitely have curtailed other duties owing to the requirements of PDS and 13 (20.9%) feel that sometimes they neglect other duties because time is needed for PDS. A total of 30 respondents (48.4%) would define the costs and effort for PDS for the hospital as high but 34 (55.8%) agree that without PDS many SSIs would not be detected. The time effort for one telephone interview and data logging was estimated with a mean (SD) of 26.3 (12.4) minutes and average costs per interview calculated with 19.69 CHF (Swiss francs). This corresponds to approximately 1,510,892 CHF for 76,734 telephone interviews in the surveillance period 2013-2014.

FIGURE 1 Comparative overview of reported workload effort and perceived importance of typical tasks of Swiss infection control practitioners.

Although PDS is able to produce more reliable SSI data compared with surveillance systems that limit the data acquisition period to the time in the hospital and readmissions, most additional captured SSIs are superficial ones,Reference Horan, Andrus and Dudeck 2 so the cost-effectiveness of routine PDS has been questioned.

In Germany efforts are underway to conduct SSI surveillance for all inpatient and outpatient surgical procedures with an algorithm based on health insurance data and using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, German procedure codes, and diagnosis-related group administrative datasets as part of the mandatory quality assurance program starting in January 2017. This approach will include the postdischarge period but will not need any input by infection control practitioners, thus freeing up their time. However, physicians who treat a case of presumed SSI detected by the automatic algorithm will be required to fill out a short questionnaire to verify the classification. International benchmarking will become more difficult, given the variety of surveillance systems from active PDS in Switzerland and the Netherlands to future “big data” mining in Germany to classical active surveillance reporting using standardized definitions.

Therefore, we believe that an internationally synchronized effort to streamline a cost-effective surveillance approach to detect SSIs is warranted, keeping in mind the RUMBA rule of meaningful quality indicators: Reliable, Understandable, Measureable, Behaviorable, and Achievable.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support. None reported.

Potential conflicts of interest. S.S.-S. reports that he is co-owner of the Deutsches Beratungszentrum für Hygiene (BZH GmbH) and receives royalties for book publishing from Springer and Schattauer publishers, Germany. E.T. reports that he is co-owner of the Deutsches Beratungszentrum für Hygiene (BZH GmbH) and receives royalties for book co-publishing from Mediengruppe Oberfranken publishers, Germany. All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.