At war with water: the Maoist state and the 1954 Yangzi floods

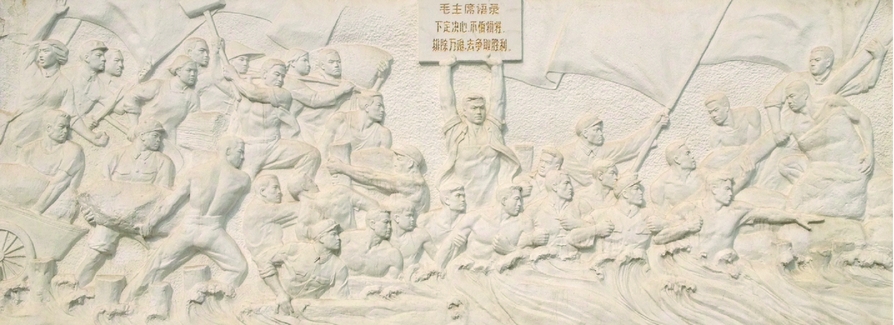

On the banks of the Yangzi River in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, the face of Mao Zedong stares down from a large stone obelisk. A casual observer might be forgiven for assuming that this image adorns some kind of war memorial. In fact, this imposing architectural feature commemorates a great flood that swept down the Yangzi in 1954. Yet this is not a sombre monument, but instead a celebration of a triumphant human victory over nature. Embossed reliefs depict heroic figures doing battle with torrents of water, clutching farm tools, shoulder poles, and political paraphernalia such as flags and banners. Figure 1 shows one such relief, in which a worker holds a slogan that reads: ‘Quotations of Chairman Mao: Be resolute and do not fear sacrifices, surmount every difficulty in order to win victory.’Footnote 1 Erected at the height of the Cultural Revolution in 1969, this monument produces an unambiguous image of a commanding state. Scholars today tend to be suspicious of propaganda produced during this period, given the extent to which the state monopolized all forms of representation. Surprisingly, however, no historian has yet challenged the triumphal narrative depicted upon this monument.

Figure 1. The 1954 Flood Memorial, Wuhan.

This article offers a critical reappraisal of the Maoist state's response to the 1954 Yangzi floods. It focuses upon Hubei province, the epicentre of the disaster. Building upon the methodology developed by scholars such as Ralph Thaxton and Jeremy Brown, it utilizes a combination of textual and oral sources.Footnote 2 Contemporary newspapers and official publications yield little reliable information, yet offer a critical insight into the operations and mentality of state, revealing how governors wanted the crisis to be understood. Internal cadre reports and disaster investigations conducted by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) provide a far greater insight into the reality on the ground, albeit one still steeped in politicized rhetoric.Footnote 3 Oral histories, in the form of 15 interviews conducted with flood survivors, help to unpick the stitches of the official narrative.Footnote 4 The memories of Hubei residents have, of course, been eroded by time and shaped by the exigencies of half a century of life experiences. Imperfect as they may be, the voices of former refugees still offer a vital corrective to otherwise mono-vocal state discourse.

The picture that emerges from these sources differs profoundly from that offered by previous histories.Footnote 5 Far from being a victory over nature, the 1954 flood precipitated a humanitarian catastrophe—possibly the most lethal inundation suffered anywhere on Earth during the latter half of the twentieth century.Footnote 6 Almost 150,000 people were killed in Hubei alone. Most casualties were concentrated in rural areas that the government flooded deliberately in order to protect urban industries. Contrary to contemporary reports, this strategy was not wholly successful, as large swathes of Wuhan were flooded, causing 20,000 people to become refugees.

What can the 1954 flood teach us about the Maoist state? Anthony Oliver-Smith has argued that disasters often act as crise revelatrice. When they strike, ‘the fundamental features of society and culture are laid bare in stark relief by the reduction of priorities to basic social, cultural, and material necessities’.Footnote 7 The flood revealed much about the political and economic imperatives governing life under the early Maoist state. One of the most pressing of these was the desire to eradicate all enemies—even if these happened to be environmental. Flood prevention was represented as a war against water, in which the state would marshal its great human resources to conquer a disaster. Given that the CCP had known little but war over the past few decades, it is perhaps unsurprising that governors treated the flood as yet another foe to be vanquished. The weapons governors chose were a series of sluice gates that released water from the Yangzi onto the plains. Unfortunately, very little thought was given to the humanitarian consequences of this hydraulic intervention. The results were catastrophic, as sluice gates were opened onto still inhabited areas.

The 1954 flood was not simply a technical failure. It was a disaster incubated by politics. With few exceptions, historians studying Maoist disaster governance have focused upon the famine of the late 1950s. This is not without justification, as it was one of the worst catastrophes in history. Recently, Lauri Paltemaa has taken a more comprehensive view, examining how the state coped with a series of disasters affecting the city of Tianjin throughout the Maoist period. He does not deny the horror of the famine, and the key role that the state played in its genesis. Yet Paltemaa also observes that, during other crises, the state responded relatively effectively. The organized labour force and the command economy facilitated efficient and expedient relief.Footnote 8 Although this article highlights a hidden tragedy at the heart of disaster governance, it concurs with Paltemaa in recognizing that, in certain respects, the Maoist state responded effectively to the 1954 flood.

At the same time, the draconian and often repressive policies enacted during the early 1950s fostered a caustic political environment, which led many citizens to distrust state representatives. This seriously inhibited disaster governance. Propagandists attempted to generate compliance by projecting an image of control and encouraging self-sacrifice. On occasions, this seemed to work. Some citizens appeared to embrace an ethos of voluntarism, if only as a somewhat instrumental performance of regime compliance. Elsewhere, communities actively resisted disaster governance, believing that the CCP was using evacuation to dupe them into forced collectivization. Ultimately, the 1954 flood revealed both the best and worst elements of CCP rule. The same structures of control that facilitated rapid mobilization and the distribution of resources also generated a sense of distrust and insecurity that was not conducive to an effective disaster-prevention campaign.

Taking over Hubei

In April 1949, a ragtag armada began to cross the Yangzi. Tens of thousands of soldiers packed onto boats, clung onto bales of straw, or drifted on inflated pigskins. These were the advanced troops of the People's Liberation Army, which had amassed 2,000,000 strong on the northern banks of the river, awaiting the final push south to secure CCP victory.Footnote 9 Having taken the erstwhile capital of Nanjing, one of the three divisions moved west. On 15 May, it entered Wuhan—the political and economic capital of the middle-Yangzi region. Five days later, a guerrilla veteran named Li Xiannian, the son of a local carpenter, was appointed as Party Secretary of Hubei.Footnote 10 As he set about pacifying the province, his forces were confronted not only by military resistance, but also by unruly rivers. In 1949, Hubei experienced the worst floods since the catastrophic deluge of 1935. Soon the dykes of the Yangzi and Han Rivers had begun to collapse.Footnote 11 The inundation slowed the advancing army, which did not complete its takeover of Hubei until November 1949.Footnote 12 The rule of the CCP had been baptized in floodwater. Over the next few years, the regime would seek to use hydraulic engineering to control the capricious rivers that had delayed their victory.

The water-control policies of the early Maoist state formed part of a broader portfolio of reforms, which were designed to consolidate political hegemony and reconfigure the economy. The government initially adopted somewhat conciliatory policies towards merchants and industrialists in urban areas such as Wuhan, limiting their activities to imposing a more disciplined system of taxation. No doubt many businesspeople longed for the days when duties could be evaded by a discreet payment to a corrupt Nationalist official.Footnote 13 Yet it was not until 1952, with the so-called Five Antis (Wufan) campaign, that the assault upon commerce began in earnest. By eroding the power of traditional elites, and organizing urban citizens through the system of work units (danwei), the CCP hoped to replace the commercial economy with state-owned enterprises.Footnote 14 This new configuration of the urban economy would have a profound influence upon the outcome of the 1954 flood. Hydraulic engineers would be called upon to protect state-owned industries at any cost, even if this involved sacrificing the countryside.

Profound as the changes to urban life were, they paled in comparison to the seismic shifts occurring in rural Hubei. Between 1950 and 1952, the countryside underwent a policy of radical land reform. Local cadres categorized families according to an inflexible class taxonomy. Those deemed landlords (dizhu) or rich peasants (funong) not only lost land and property, but were also subjected to violent persecution and even execution. Meanwhile, the army undertook a series of pacification campaigns to obliterate the last vestiges of resistance.Footnote 15 Land reform proved highly popular amongst its beneficiaries. Before long, however, it became clear that this great redistribution was not all that it appeared. Rural communities were subjected to highly extractive requisitioning policies. The state grain monopoly, which was introduced in 1953, compelled farmers to sell their surplus to the local government at a fixed price. This was followed in the spring of 1954 with a nationwide drive to subsume individual households within larger agricultural cooperatives. The presumed efficiency savings offered by these policies were to form the economic foundations of state-led industrialization.Footnote 16 The countryside was to provide the economic fuel to power the engine of urban industrial growth.

It is tempting to posit a clear line of evolution between these early rural policies and the famine that raged during the Great Leap Forward of 1958–1961. Unrestricted grain requisitioning and the creation of People's Communes—which were cooperatives mutated to gargantuan proportions—would eventually drive tens of millions to their graves. Yet it is important not to submit to an overly teleological narrative. Hayekian scholars such as Frank Dikötter and Yang Jisheng have argued that early collectivization set China off along the ‘road to serfdom’, creating a politico-economic dynamic that would inevitably lead to disaster.Footnote 17 Dikötter has argued that the state grain monopoly resulted in food shortages in many areas, including Wuhan, as early as 1954.Footnote 18 Within his analysis, there is no mention of the flood, which caused one of the worst weather-induced production shortfalls of the twentieth century.Footnote 19 Whilst by no means denying the detrimental effects of Maoist economic policies—particularly the millions killed by famine—historians such Li Huaiyin and Y. Y. Kueh have noted that collectivization had numerous beneficial effects, including considerable infrastructural and health-care developments.Footnote 20 Since the 1950s, there has been a measurable improvement in Chinese life expectancy. Whether this was because of or in spite of collectivization remains a matter of debate.Footnote 21

The 1954 flood highlighted both the benefits and detriments of early Maoist governance. Collectivization offered what Kueh has described as an ‘institutional hedge’ against the effects of climatic disasters. Work units facilitated the rapid deployment of flood-prevention labourers and the state-controlled grain market enabled more efficient relief distribution. At the same time, however, revolutionary politics inhibited disaster governance by engendering a sense of insecurity. Those who had benefitted from land reform guarded their new property fiercely, whilst those who had suffered feared a further erosion of their livelihoods. Trust was diminished further by rapacious extraction of grain. The insecure atmosphere in rural Hubei made disaster governance far more difficult.

Taming the Yangzi

In 1952, the journalist Di Lei offered a typically ideological interpretation of Hubei's historic water-control problems. The cause of the disastrous floods that had long blighted the lives of the local population, it was argued, was class prejudice.Footnote 22 As Imperial and Republican administrators did not suffer personally during inundations, they were not invested in finding a solution to the root causes of hydraulic failures, being content merely to alleviate the symptoms of flooding. This politicized reading of history ignored the numerous elite figures, such as the late Qing polymath Wei Yuan, who had argued vehemently for systemic reform of the hydraulic network.Footnote 23 More importantly, this crude caricature posited human agency as the sole variable determining disaster causality. In reality, flood disasters were both environmental and anthropogenic. Humans had exacerbated natural risks by converting floodplains into arable land. The dykes they constructed to ameliorate the resultant inundations over time exacerbated flood risk, particularly when poorly maintained. The deluges that occurred when hydraulic networks failed were more dangerous than natural floods. The most lethal occurred when the Great Jingjiang Embankment running parallel to the Yangzi collapsed, releasing the river onto its plains. From the nineteenth century, the intensity and frequency of flooding increased dramatically.Footnote 24 The most lethal inundation occurred in 1931, when a nationwide disaster killed in excess of 2,000,000 people.Footnote 25

In February 1951, the government commissioned the Yangzi Conservancy Authority (Changjiang shuili weiyuanhui) to solve the problem of flooding in Hubei. Chinese engineers, aided by Soviet advisers, designed a series of flood-diversion areas (fenhong qu) near the cities of Jiangling and Shashi in Jingzhou prefecture, central Hubei. Sluice gates would divert the Yangzi onto the plains when floods threatened. This area would then be drained through another series of sluice gates when water levels had decreased.Footnote 26 This scheme met with the highest approval. Mao Zedong himself proclaimed: ‘For the great benefit of the people, be victorious in the construction of the flood diversion.’Footnote 27 The project utilized the full strength of CCP mass mobilization. Three hundred thousand labourers completed construction in just 75 days in the spring of 1952.Footnote 28 Conditions were tough, with labourers being forced to work, eat, and sleep in a damp environment plagued by malarial mosquitoes.Footnote 29

The flood-diversion project coincided with the nationwide Three Antis (Sanfan) campaign, during which the CCP sought to eliminate corruption, waste, and bureaucracy. Workers were forced to spend their resting hours undergoing no doubt tedious meetings and self-evaluations. The politicization of the project escalated during the subsequent Five Antis campaign. A local supplier named Wu Xingce was accused of being an ‘evil merchant’ (jianshang) for supposedly providing substandard construction materials.Footnote 30 Skimming off hydraulic projects had been fairly common in the Republican era. Hubei was littered with jerrybuilt dykes as a result.Footnote 31 It is impossible to determine whether Wu was genuinely guilty of this offence, or whether the CCP made an example of him in order to undermine the power of commercial elites. This episode demonstrated the extent to which all aspects of life had become politicized and, for some, intensely precarious.

Whilst workers and merchants suffered, it was the rural majority who bore the brunt of the flood-diversion project. Those living in areas designated for inundation were to be relocated to one of ten specially designated safety areas (anquan qu). By March 1952, over 60,500 people had been resettled. Others were reluctant to abandon their ancestral homes, even when offered incentives such as money, food, and tractors.Footnote 32 Compulsory relocations have been a perennial feature of CCP hydraulic governance. The anthropologist Jun Jing revealed the deep trauma suffered by one community dislocated from its proud heritage by the construction of a dam.Footnote 33 The history of the forced evacuation of Hubei's flood-diversion area has yet to be written. Clearly, it was not entirely successful. Many people continued to live in now acutely vulnerable areas. This was to have tragic consequences when the sluice gates were opened in 1954.

Any description of a monumental water-control project cannot help but evoke the spectre of Karl Wittfogel. This historian characterized imperial China as one of a number of ‘hydraulic societies’ in which the imperative to prevent floods or irrigate arid landscapes helped to foster a highly centralized mode of governance. He described this as ‘oriental despotism’.Footnote 34 The vast archive pertaining to the history of water control in China has proven Wittfogel largely wrong, at least for the late imperial period. Hydraulic governance was typically highly localized, with the central state preferring delegation to megalomaniacal control.Footnote 35 Ironically, at the same time as Wittfogel was penning his most famous exposition of oriental despotism, the Maoist state was beginning to exert unprecedented control over the hydraulic network. In the decades to come, the CCP would reshape the hydrosphere more profoundly than any polity in history. It might be tempting, then, to turn Wittfogel on his head, suggesting that it was not until the state achieved despotic power that it was able to create a fully hydraulic society. Yet, even at its most commanding, the CCP state never enjoyed the kind of power that Wittfogel envisioned. The 1954 flood demonstrated that the government could control neither rivers nor people completely.

At war with water

It started raining in the spring of 1954 and did not stop for 58 days.Footnote 36 Soon, around 1,500,000 people in Hubei had fallen victim to mountain flooding (shanhong), as great surges of water and debris swept along the tributaries that drained the highlands. Those not drowned found their fields covered in sandy deposits, leaving them uncultivable. On the plains below, some 2,250,000 people suffered less dramatic yet no less devastating waterlogging disasters (zizai). They spent the spring struggling to drain their fields, as the rain poured down unremittingly. Having lost their summer crops, many were prevented from planting a winter insurance harvest. The worst was yet to come. A series of storms struck in July, causing local dykes throughout Hubei to suffer breaches (kuikou).Footnote 37 Around 3,780,000 people were inundated as river water was funnelled through the artificial topography onto their homes. One former farmer recalled in an interview how she was carrying manure to the fields when she heard people crying and shouting: ‘I turned around to see a huge wave. It was really white, like a sheet.’ Another described how his family had scrambled to their boat in order to flee to a local hillside. Many were not so fortunate. Thousands were drowned or buried alive by the cascade. By the summer of 1954, more than 10,000,000 people—nearly two-fifths of Hubei—were under water.Footnote 38

The engineers tasked with maintaining the hydraulic system now sought desperately to prevent further destruction. Their Republican predecessors had been fond of quoting water-control treatises by classical theorists such as such Mencius.Footnote 39 In 1954, chief engineer Tao Shuzeng chose instead to quote the military theorist Sun Zi, enjoining his fellow engineers to ‘know themselves and their enemies (zhiji zhibi)’ so that they might win their ‘battle (zhandou)’ with rivers.Footnote 40 Judith Shapiro has argued that such highly combative rhetoric reflected the ultra-utilitarian environmental attitude of the Maoist state. Yet, if the language of conflict was particularly prevalent in CCP rhetoric, this had as much to do with decades of warfare as it did with ideology. Pamela Crossley has observed that the cessation of hostilities in Korea in 1953 marked the end of an unbroken chain of armed conflicts that stretched right back to 1926.Footnote 41 With Taiwan still under Nationalist control, war remained a distinct possibility. Politicians saw the 1954 flood as part of this broader existential struggle. As the People's Daily (Renmin Ribao) put it: ‘the imperialists and Chiang Kai-shek . . . cannot fight us, and so hope that natural disasters will destroy us.’Footnote 42

Chinese leaders were still war leaders—their mode of thinking combative by default. This influence went beyond the military allusions that peppered official discourse. It permeated the governance style of the CCP.Footnote 43 Ralph Thaxton has noted how the wartime legacy begat a confrontational work style, leading cadres to make hasty and unilateral decisions.Footnote 44 Hydraulic governors were subject to a similar urgency of command, adopting bold strategies with little thought for the humanitarian consequences. Having convinced themselves they were at war with water, they were determined to win regardless of the collateral damage. By the summer of 1954, they already lost a number of battles, and an estimated 6,660,000 mu (4,400 km²) of land was under water as a result.Footnote 45 Yet Wuhan had yet to be flooded. In the ensuing months, the city would become the front line, its defence determining the outcome of the war. The race was now on to save Wuhan.

Chinese flood-prevention campaigns have always required vast amounts of labour. Previous political systems had extracted this through various forms of compulsion, most often corvée labour or work relief. Although labour was no less compulsory for the soldiers, work units, and rural citizens sent to the dykes in 1954, propagandists were determined to portray the campaign as a voluntary enterprise. Periodicals such as the Yangzi Daily (Changjiang Ribao) published accounts of heroic workers dedicating themselves to the war against water.Footnote 46 These exemplars embodied a mode of compulsory volunteerism, which would become a defining feature of Maoist political culture. They displayed an unwavering dedication to labour—much like the Stakhanovite workers of the Soviet Union—yet also indulged a penchant for ostentatious acts of self-sacrifice.Footnote 47 Within the evolution of the ideal Maoist subject, they occupied a position somewhere between the heroism of celebrated wartime martyrs and the trudging obedience of the most famous of exemplars: Lei Feng—the smiling peasant/soldier/worker who was content to be an anonymous screw in the revolutionary machine.Footnote 48

Wang Maoshan was a typical flood hero. He was reported to have worked for nine days without rest, spending several hours neck deep in sewage. He continued to stack sandbags even after he had developed a heart complaint.Footnote 49 Such labouring masculinity and disregard for personal safety was not reserved solely for men. Lu Youzhi was pictured plunging herself into freezing water in order block a breach, using her own body as a weapon against water.Footnote 50 In a marked contrast to Confucian norms, worker heroes ignored even the most sacred of personal obligations, choosing flood prevention over kin and home. Wang continued to work even after his wife fell ill, and Lu abandoned her own children to head to the dykes.Footnote 51 The message was unequivocal—dedication to the state superseded all other considerations.

Exemplar narratives were often so outlandish that they bordered upon self-parody. This does not mean they did not work. A retired factory worker from Wuhan recalled in an interview how members of his work unit genuinely had wished to participate in the flood-prevention campaign. Rather than being motivated by patriotic fervour or revolutionary zeal, however, they were keen to be seen as key ‘activists’ (jiji fenzi) within the work unit. Such a designation was of no little significance. Susan Shirk characterized Maoist China as a ‘virtuocratic’ society, in which career advancement was based more upon a reputation for political correctness than it was upon any form of occupational competence. In this respect, exemplar narratives offered a vital script for ordinary citizens to enact the kinds of instrumental performances that helped them to gain merit in the eyes of the state.Footnote 52

Not everyone was dedicated to the war against water. One internal cadre report noted that large crowds of young men were choosing to sit around in teahouses rather than participating in flood prevention.Footnote 53 Worse still, a local history described how criminal elements (bufa fenzi) were arrested for attempting to sabotage the relief effort in Wuhan.Footnote 54 Why and how they did so is not divulged. Later, several merchants were executed for the crime of ‘making up rumours to cheat the masses’ (zaoyao huozhong), having attempted to hoard grain to inflate prices.Footnote 55 The reports of these class enemies represented a dark inversion of exemplar narratives. Flood heroes were celebrated for embodying the norms promoted by the new state. Those who subverted these norms could expect little mercy. In this respect, the war against water formed part of the broader project to remould Chinese citizens.

Drowning the countryside

Even with a vast army of workers piling sandbags into breaches and propping up dykes, the government could not stop the gigantic flood peak travelling downstream towards Wuhan. On 19 July, governors decided to unleash their ultimate weapon: the newly finished Yangzi Flood Diversion. They opened the first of several sluice gates at a place named Yuwang Gong—or Palace of King Yu—in central Hubei.Footnote 56 The symbolism of this location cannot have been lost upon the local population. The mythic King Yu had established dynastic authority in ancient times by taming a great flood.Footnote 57 By opening the sluice gate, the CCP now linked its own legitimacy to hydraulic mastery. This initial diversion proved insufficient. Over the course of the next few months, the sluice gates were opened on a further two occasions.Footnote 58

The flood diversion was represented as a great advance in environmental management. In reality, it was defeat masquerading as victory. The government had gifted the Yangzi a floodplain before it could forge its own. Just as propagandists had transformed the scrambled retreat of the Long March 1934–35 into a symbol of the tenacity of the CCP, now they represented the inundation of thousands of mu of valuable agricultural land as a masterstroke of environmental management. The People's Daily heaped praise upon rural communities for ‘voluntarily allowing their villages to be flooded, thereby sacrificing their own wellbeing in order to save the city’. A farmer was quoted as saying that ‘industrial construction is the great life root (daming genzi) of the people, and so had to be protected’.Footnote 59 The CCP were not the first to mobilize the rhetoric of sacrifice. Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley has described how the Nationalists portrayed those who were deliberately inundated by the breaching of the Yellow River dykes in 1938 as martyrs in the war against Japan.Footnote 60 What was novel in 1954, perhaps, was the extent of a ventriloquist state depicting its own rhetoric issuing forth from the mouths of the people.

Not only had the government destroyed the homes and livelihoods of rural citizens; it now had the temerity to suggest that it had done so with their willing compliance. In reality, those living in flood-diversion area had not volunteered their homes. The order to open the sluice gates was imposed upon them. Furthermore, beneath the highly politicized rhetoric of cadre reports, there were hints that something was going seriously wrong in the diversion zone. The government had completed an ambitious hydraulic project but had not prepared an adequate plan to manage the inevitable consequences. Now they were called upon to conduct a rapid evacuation of the affected zone. Unfortunately, many people were extremely reluctant to leave their homes.

Resisting government evacuation is by no means unusual. Members of flood-threatened communities from areas as diverse as Mozambique, India, and New Orleans have all refused to be relocated.Footnote 61 Often disparaged as ignorance, such behaviour is usually rooted in an understandable desire to protect property. In as much as this basic material concern played a role in 1954, residents of Hubei were also influenced by their particular political context. Villagers in Jianli County explained that they did not want to evacuate, as to do so involved carrying their property out in the open, thereby ‘exposing their wealth (loufu)’. The official who reported this behaviour attributed it to ‘bad elements (huai fenzi)’ in the village, who had spread rumours that the government was planning to use the flood as an excuse to further collectivize property.Footnote 62 Villagers had good reason to be cautious, given the extent to which property had been dispossessed and redistributed by the state in recent years. Their fears were in fact quite prescient. Over the next few years, the state really did appropriate their property and force them to live in communes.

Another cadre reported how the class taxonomy introduced by the CCP was influencing refugee behaviour. Those considered middle or rich peasants did not want to be relocated, as they believed that the government would only provide relief to those designated as poor peasants.Footnote 63 This, again, was not unreasonable, given the extent to which those with unfavourable class designations had been excluded from earlier government policies.Footnote 64 The situation was even worse for the most hated class enemy—the landlords, who were so convinced that no relief would be forthcoming that they simply ‘surrendered to fate (tingtian youming)’. Cadres conducted a propaganda campaign designed to allay such ‘ideological concerns (sixiang gulu)’. This could hardly undo the insecurity fostered by years of political campaigns.

When officials attempted to evacuate a village in Qianjiang, the local population shouted abuse at them. Elsewhere, the army resorted to firing guns and artillery into the waste ground surrounding a village and shouting the names of well-known ‘bandits’ in an attempt to intimidate people into departing.Footnote 65 Even when villagers could be persuaded to leave, the government struggled to maintain order. Cadres in Jianli attempted to follow an efficient methodology in which those with poorly constructed homes in low-standing areas were to be moved first. Priority would be given to the elderly and infirm, and to the families of soldiers.Footnote 66 Before they could implement this methodology, however, local villagers began fighting in order to board boats, causing people to drop salvaged property into the water.Footnote 67

The problems did not end with evacuation. Host communities often proved less than welcoming to members of the displaced population.Footnote 68 Reluctance to house refugees is hardly unusual during a crisis.Footnote 69 Once again, however, local attitudes were informed by the political context. Cadres in Honghu worried that refugees would diminish production levels and villagers feared that an influx of outsiders would spark a second wave of land reform. One reasoned that ‘It is OK for refugees to come, but I don't have much land, I cannot give any away’.Footnote 70 Citizens of Wuhan also grumbled about refugees, complaining that they were not working hard enough.Footnote 71 If these urbanites failed to appreciate the sacrifice made by their rural compatriots, it was hardly their own fault. Contemporary media reports said nothing of the great misery caused by the drowning the countryside, choosing instead to focus upon the miraculous defence of Wuhan. Here, too, the official story was not all that it appeared.

Unsinkable Wuhan

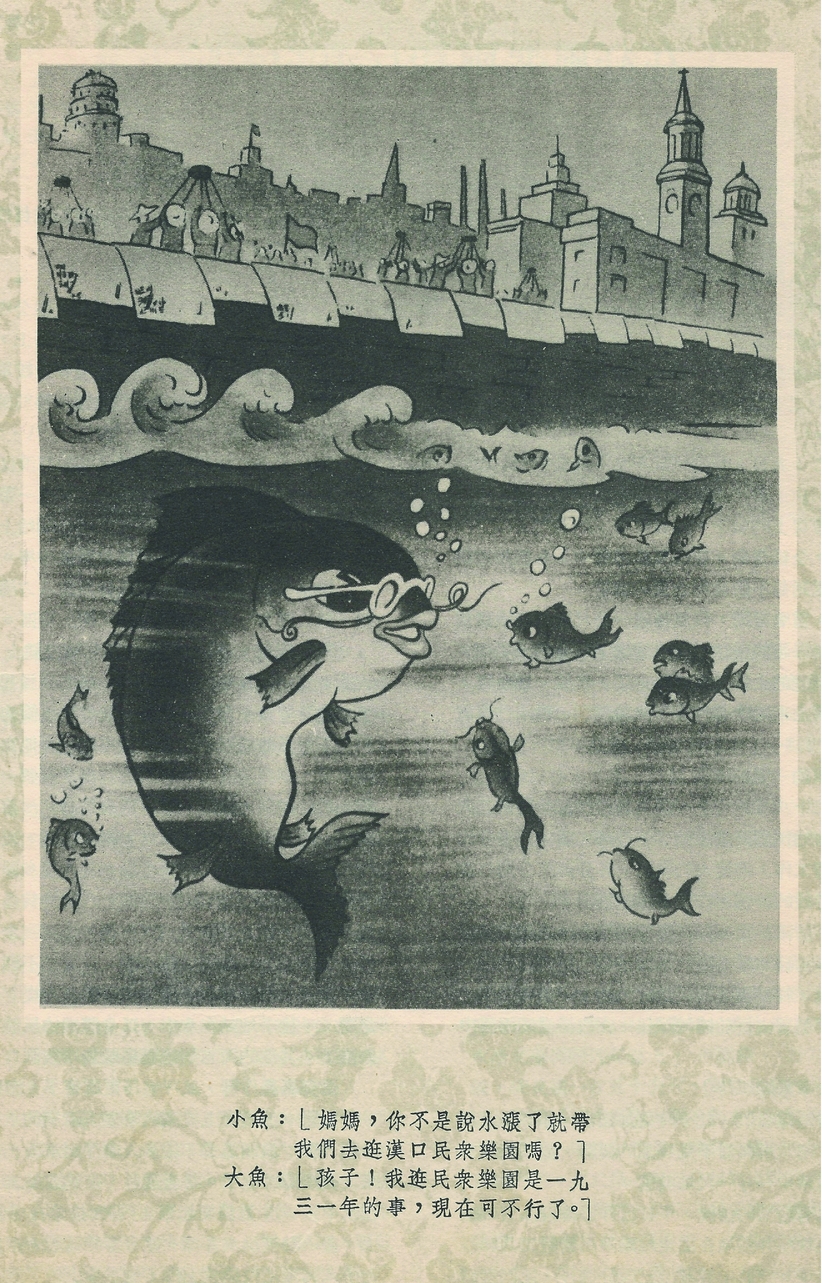

The defence of Wuhan was heralded as the crowning achievement of the flood-prevention campaign. In 1955, the Hubei Water Conservancy Bureau published a commemorative volume entitled The Party Leads the People to Victory over the Flood (Dang lingdao renmin zhanshengle hongshui).Footnote 72 This hagiographic account was designed not only to celebrate the successful flood-prevention campaign, but also to contrast CCP disaster management with supposed inefficiency and corruption of the Nationalist regime. Photographs of dry and orderly city streets taken in Wuhan in 1954 were juxtaposed against chaotic scenes of inundation in the city in 1931. The volume also included a cartoon depicting a mother fish talking with her spawn against the backdrop of Hankou's distinctive skyline (Figure 2). In the caption below, a young fish asks why he cannot visit one of Wuhan's leading attractions: ‘Mummy, didn't you say that when the water rose you would take us to Hankou's Minzhong Amusement Arcade?’ The mother fish replies: ‘Child, visiting Minzhong was something I did in 1931, that couldn't happen now.’ The message was unequivocal—to the dismay of the local fish population, urban flooding was a thing of the past.Footnote 73

Figure 2. A cartoon from The Party Leads the People to Victory over the Flood, 1955.

By comparing 1931 and 1954, propagandists were able to construct a narrative that adhered to what the literary historian Gang Yue has described as the ‘bitter/sweet dichotomy that organized the revolutionary teleology’.Footnote 74 The successful defence of Wuhan was not simply a victory over water, but also a victory over history. This politicized reading of the disaster was reproduced in the English-language book Man Against Flood, written by the New Zealand expatriate Rewi Alley, a leading foreign spokesperson for the Maoist regime. Alley was well placed to make a comparison, having visited Wuhan during both floods. He claimed that, in 1931, the Nationalist regime was ‘so wildly corrupt it permitted graft, speculation and stupid inefficiency to go hand in hand with relief measures’.Footnote 75 In 1954, by contrast, ‘the people of Wuhan worked a miracle’, protecting a key industrial centre from inundation.Footnote 76 It is difficult to determine whether Alley was being deliberately mendacious or whether he had been duped by a carefully stage-managed tour of Wuhan.Footnote 77 Whichever was the case, the heroic victory he described stretched the truth to breaking point.

The modern city of Wuhan comprises the three historic municipalities of Wuchang, Hankou, and Hanyang. Although the former two areas had genuinely been protected from inundation, Hanyang suffered several months of serious flooding and a major refugee crisis. The problem was due in a large part to inadequate flood defences. Unlike Hankou and Wuchang, which boasted dykes reinforced with concrete, Hanyang still relied upon defences constructed from tamped earth, clay, and coal slag.Footnote 78 These crumbling structures were inadequate protection against the oncoming deluge. By July, the 7,751 workers who had been sent to bolster the city's defences had run out of earth. Soon, a number of key dyke sections began to collapse. In desperation, engineers directed workers to protect key industrial sites, including a lumberyard and cotton mill.Footnote 79 In doing so, they effectively surrendered vast swathes of residential housing to water. The inundation of Hanyang mirrored the broader dynamic unfolding throughout Hubei. The homes of workers were sacrificed so that their factories might survive. Around 26,300 Hanyang residents became refugees as a result.Footnote 80

In spite of claims that the revolution had improved the lives of the ordinary population, many citizens of Hanyang still lived in intense poverty. Older residents still recall the simple huts (pengzi) constructed from reeds and other inexpensive materials that were erected on lakeshores and riverbanks in the city. These were acutely vulnerable to inundation. One family who moved from the rural hinterland to work as porters were living in a riverside area at the time of the flood. When large waves began threatening the Dragon Lantern Dyke that protected their neighbourhood, they were forced to gather their possessions and flee to Turtle Hill. Here they built a small shelter on the former cremation grounds of a local Buddhist monastery. They lived for months amidst the charred remains of monks. Similar camps mushroomed up on the hillsides, dyke tops, and other areas of high ground, which had formed an archipelago of flood islands throughout Hanyang. One interviewee recalled how residents of Parrot Island—a fluvial deposit located in the river between the Wuhan cities—were forced to crush into the classrooms of a local school, living there for months. The experiences of these people are missing from both contemporary media reports and subsequent histories, which focus upon Hankou and Wuchang and ignore the large sections of Wuhan lost to water.

This was not the first refugee crisis in Hanyang. During the late imperial period, those displaced by disasters had relied upon government granaries and charitable organizations, including guilds, benevolent halls, temples, and native place associations.Footnote 81 In the early twentieth century, these traditional organizations had been augmented by the growth of influential national and international charities.Footnote 82 Unlike the Nationalists, who had sought to co-opt the expertise and resources of both traditional and modern institutions, the CCP took a decidedly dim view of private charity, seeing it as a bourgeois obfuscation—a mere palliative for the class exploitation that was the root cause of disasters. Undermining private philanthropy formed part of the broader attack upon traditional sources of elite legitimacy, which had begun in earnest with the Five Antis campaign.Footnote 83 The 1954 flood represented one of the first real challenges for the economic infrastructure that the CCP had introduced in order to replace traditional charitable institutions.

The Nationalists had funded the 1931 flood-relief effort with hastily issued bonds and costly foreign loans.Footnote 84 The CCP was much better placed, being able to utilize a fully nationalized banking sector. The People's Bank of China provided a 300,000 RMB emergency loan to Wuhan alone.Footnote 85 The government also initiated large-scale interregional grain transfers—a policy that echoed the economic interventions made by the Qing state during the eighteenth-century golden age of disaster governance.Footnote 86 Soon, emergency aid was arriving in Hubei from as far afield as Guangdong, Henan, and Sichuan.Footnote 87 The state grain monopoly may not have been universally popular and its abuse at the end of the 1950s would be a major cause of famine, yet, at this time of crisis, it provided an expedient means of organizing relief.

Media reports heralded the disaster-relief campaign as an unqualified success. Shops laden with food in 1954 were juxtaposed with images of starving refugees in 1931.Footnote 88 Although this was clearly a highly partial view of events, those who lived as refugees in Hanyang tended to corroborate this positive assessment. The relief effort is remembered as a highly organized and well-provisioned affair. ‘Chairman Mao was very good,’ one now elderly woman recalled. ‘He didn't let us starve. Every family got steamed bread.’ Another former refugee marvelled at how the government had used airdrops to feed those isolated on hillsides. The picture may not have been quite as rosy as these refugees recalled. Cadre reports show that outbreaks of malaria and gastrointestinal disease took a heavy toll upon refugees in Hanyang.Footnote 89 Rather than recalling such hardships, memories of the flood tended to be tinged with a degree of nostalgia. This is fairly typical, as many older Wuhan residents still view the collective era as relatively egalitarian and incorrupt. Yet we cannot simply dismiss these positive memories. The near universal praise heaped upon governors in 1954 suggests that, in Hanyang at least, the disaster was managed relatively well. One interviewee even went so far as to suggest that being a refugee was preferable to his everyday life at the time. At least in the camp, he received a daily ration of food. Unfortunately, these positive experiences were not shared by many of those living in the countryside, where the flood had resulted in widespread hunger and disease.

Death in the countryside

The Chinese government has always maintained that the 1954 flood resulted in a relatively limited loss of life. Contemporary media reports offered virtually no descriptions of death, save for a few accounts of exemplars martyred in the war against water. The officially recognized death toll, compiled by the State Statistical Bureau in the 1990s, puts the figure at 33,160 fatalities throughout China.Footnote 90 Although not an inconsiderable loss, this mortality rate was well below the estimates for the 1931 flood, when anywhere between 400,000 and 2,000,000 people died.Footnote 91 Quite how the official death toll for 1954 was calculated remains a mystery. This has not stopped the figure from becoming the standard cited by both local and foreign historians.Footnote 92 There is, however, an alternative set of statistics that offer a very different picture of the flood. An internal disaster investigation carried out by the CCP in early 1955 suggests that 149,507 people died in Hubei alone.Footnote 93 The report categorizes victims in accordance with their cause and place of death, suggesting that this investigation had a coherent methodology. These statistics are corroborated by another cadre report, which suggests that, between July and November 1954, around 132,221 people had died.Footnote 94

These reports demonstrate that around five times as many people died in the flood than has been officially acknowledged. Somewhere in the journey between internal reports and officially published statistics, the lives of well over 100,000 people simply disappeared from history. What truly occurred during the flood is obscured beneath layers of euphemism and politicized rhetoric in official reports. The few glimpses that are revealed when this veneer slips, coupled with the insights offered by oral history, provide valuable clues as to what went wrong. Famine had historically been one of the most significant problems facing flood-stricken populations in China. Although refugees in Wuhan in 1954 may have marvelled at the generosity of the state, the same could not be said for their rural counterparts. One farmer from Shaomaoshan remembered receiving very little state assistance. Instead his family fell back upon traditional coping strategies, eating unripe rice and beans salvaged from the flood. When these stocks ran out, the family relied upon assistance offered by kinship networks. The propaganda celebrating a victory over the flood did not resonate with this individual's experiences: ‘We were very pitiful (zaoye),’ he recalled. ‘I feel very miserable thinking about those times.’Footnote 95

Not all rural areas suffered such profound privation. Cadres in Huangpi were fêted as ‘Buddhas of salvation (jiuming pusa)’ after they distributed food and oil to the local population.Footnote 96 Yet, even in areas where the state was able to provide relief, there were often still food shortages. Soon rural populations began to display the symptoms of acute economic distress.Footnote 97 Cadres in Honghu bemoaned the fact that refugees had spent relief funds on begging bowls, seeing this as an expression of misguided ideology rather than desperation.Footnote 98 The re-emergence of mendicancy was particularly galling, as the eradication of begging had been one of the most celebrated victories of the early CCP government.Footnote 99 Elsewhere, farmers sold their cattle—a desperate act given the vital role these animals played in the pre-mechanized agricultural system. Many people went to great lengths to save their oxen and buffalo from drowning, only to find they had no fodder to feed them. By the autumn, cadres were reporting that ‘evil merchants’ were travelling from Hunan to purchase cattle at minimal prices.Footnote 100 Asset speculation had been a mainstay of Chinese disasters for centuries.Footnote 101 It would seem that, even after the Five Antis campagin, this rapacious form of economic exploitation was still thriving.

In spite of the obvious distress caused by the destruction of the main summer harvest, there is little evidence to suggest that Hubei sank into a full-blown famine in 1954. The disaster investigation suggested that a mere 69 people had died as the result of exposure and starvation.Footnote 102 Rural communities may have been begging and divesting assets, but they do not appear to have been selling family members, and they certainly did not engage in cannibalism, as famished people sometimes had in the past and would again at the end of the 1950s.Footnote 103 The official relief campaign no doubt played a role in preventing starvation. Yet people from Hubei were formidable flood survivalists. Cadres praised the autonomous actions of farmers, who began to plant and even clear new land at the height of the flood.Footnote 104 When the water receded, people used buckets to catch the fish stranded in pools. Counterintuitive as it may seem, some interviewees actually remembered the flood as a time of plenty due to this nutritional windfall.

When it comes to famine, absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence. It is possible that investigators may have chosen for political reasons to attribute starvation fatalities to disease. During the Great Leap, famine was sometimes described as a medical emergency to render it more politically palatable.Footnote 105 It is also possible that some people did not have time to starve to death, as they succumbed to infections first. Throughout history, disease has always been the leading proximate cause of flood mortality, far outstripping the threat from drowning or starvation. 1954 was no exception. Most of those who died succumbed to disease. Dysentery, gastroenteritis, and other diarrheal conditions accounted for almost two-thirds of all disease fatalities.Footnote 106 Contagious diseases such as measles and influenza were the second most lethal. Malaria, which ordinarily thrived during Yangzi floods, accounted for a mere 5 per cent.Footnote 107 In the aftermath of inundation, haemorrhagic fever and schistosomiasis swept through a weakened population, helping to raise death rates to 15 per 1,000.Footnote 108

Of the approximately 10,000,000 people in Hubei affected by the disaster, by far the largest proportion could be found in Jingzhou, the prefecture where flood diversion was located. This area not only had the largest aggregate population of refugees, but also by far the highest per-capita mortality (see Table 1). It was home to around 40 per cent of flood victims, yet suffered almost 70 per cent of all fatalities. We are unlikely to ever know the truth about what went wrong in this prefecture. From the internal report, we learn that the three most severely affected counties were Mianyang (25,702 fatalities), Jianli (32,627), and Honghu (21,092). Other areas suffered from mountain flooding, waterlogging, or dyke failure, yet it was the three counties that the government flooded deliberately that had by far the highest rate of mortality.

Table 1 Flood mortality in Hubei, 1954.Footnote 109

The government cannot be held entirely responsible for these fatalities. Even had they not opened the sluice gates then, it is estimated that around 70 per cent of this region would have been inundated.Footnote 110 The diseases that drove mortality were density-sensitive, meaning that the per-capita mortality rate was bound to by highest in the area with the largest concentration of refugees. Yet there were clearly some woeful inadequacies in disaster management in Jingzhou, which helped to create beneficial ecological conditions for the types of pathogens that cause gastrointestinal disease. One report from Honghu described how displaced people were defecating and urinating freely around their living area. Cadres sought to shift the blame onto refugees, claiming they lacked adequate hygienic education. Arguably, however, the fact that refugees had not been provided with even the most basic facilities is a bitter indictment of disaster governance.Footnote 111 Propagandists heaped praise upon the population of the flood-diversion zone for sacrificing their homes. In reality, rural refugees were abandoned to live in abject conditions. Given that this was a planned flood, the failure to evacuate and rehouse refugees is quite incomprehensible. Governors concentrated upon elaborate technical interventions and yet did not plan for the humanitarian consequences of the flood diversion.

This neglect continued in the months following the flood. According to contemporary propaganda, by saving Wuhan, the government had retained the economic and infrastructural capacity to reconstruct the whole province.Footnote 112 In contrast to this positive picture, refugees from Hanyang remembered reconstruction as an arduous and unpleasant process. They had to return to live in homes that were coated in thick layers of malodourous mud. In the countryside, things were even worse. One interviewee described returning to his farm to find all his crops washed away and his draught animals dead. His family then had to live with little food through a bitterly cold winter in a hastily improvised shack. He was luckier than many of his neighbours, who had been killed in the flood. The bitter reality of post-disaster life perhaps goes some way to explaining why an epidemic of suicide began to sweep through Hubei. Once again, residents of the flood-diversion zone were the hardest hit. Of the 2,010 people who took their own lives during the disaster in Hubei, some 1,349 were from this area.Footnote 113 These desperate people, whose communities and systems of subsistence had been sacrificed to save other areas, faced a future of economic hardship and acute insecurity. Those who chose to take their own lives were the last unacknowledged casualties of the war against water.

Conclusion

The 1954 flood laid bare a brutal irony of the Chinese revolution—a political project that had swept to power by mobilizing millions of rural citizens chose repeatedly to sacrifice the countryside in order to develop the city. Some of the communities that were flooded deliberately had supported the CCP loyally since as early as the 1920s, providing assistance to guerrilla forces fighting against the Nationalists and Japanese.Footnote 114 One was so renowned that it was celebrated in the 1961 motion picture The Red Guards on Honghu Lake (Honghu chiwei dui).Footnote 115 This loyalty counted for very little as the sluice gates were opened. This deliberate flooding was an extreme example of the kind of urban bias that Jeremy Brown has described as typical for the Maoist era. Policies that aimed ostensibly to eliminate distinctions between the countryside and the city actually sharpened the divide. This was most evident during the Great Leap famine, yet could also be discerned when millions of urban youths were dumped on the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 116

The Maoist state is not the only polity in history to have sacrificed rural lives to rivers. The most obvious comparison is with the Nationalists, whose generals deliberately breached the Yellow River dykes in 1938 in a desperate attempt to slow the Japanese advance.Footnote 117 Qing commanders adopted a similar approach in 1856, albeit on a smaller scale, using the Juzhang River as a weapon against their Taiping enemies.Footnote 118 Looking beyond China, the United States Army Corps of Engineers blew up levees in 1927, unleashing the Mississippi onto rural districts in order to protect New Orleans.Footnote 119 The 1954 flood diversion was not, then, a peculiar pathology of Maoist ideology. Neither was it morally indefensible. Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley has described the Nationalist decision to unleash the Yellow River as a ‘pragmatic response to a terrible situation’.Footnote 120 The same could be said of 1954. We need look no further than 1931 to see how much more profound the humanitarian consequences could have been had the whole of Wuhan been inundated. Not only would millions of urban citizens have been plunged into water; the province would also have been deprived of its economic centre. Those who opened the sluice gates were neither heroes nor villains. In as much as their decision has been distorted terribly within hagiographic official histories of the flood, it cannot be explained by the form of demonographic analysis that is sometimes deployed within the popular historiography of Maoist China. This was a complex zero-sum calculation, which belies attempts to transform history into a political cautionary tale.

Hubei would have flooded in 1954 no matter which political party was at the helm. Whether the humanitarian consequences would have been the same is a different question. The CCP seems to have managed some aspects of the relief effort relatively well, taking advantage of increased control over labour, finances, and grain. Contrary to the view of historians who feel we must apply a totalizing logic when analysing the Maoist economic system, the experience of the 1950s reveals that the collective economy was good at some things and bad at others. One area where it seemed to thrive was in distributing resources during relief campaigns. The generally positive memories of refugees in Hanyang were hardly exceptional. Members of communities that experienced the Wei River Floods in Henan in 1956 and the Hai River Floods in Hebei in 1963 also spoke highly of government relief efforts.Footnote 121 This relative efficiency renders the mass starvation of the late-1950s even more incomprehensible. During these so-called Three Years of Natural Disasters, a government that had learnt to deal relatively effectively with acute subsistence crises fell back on the oldest excuse in the book—blaming their economic mismanagement upon the weather.

If the state was able to organize effective relief, then why did so many people perish in Hubei in 1954? The answers are more political than economic. They involved both the micropolitics of the village, where distrustful farmers felt that they were being duped out of land, and the macropolitics of hydraulic governance, with engineers giving insufficient thought to the collateral damage caused by hydraulic interventions. Each of these spheres speaks to a political system that, as Yang Jisheng has argued, lacked an effective feedback mechanism between society and state.Footnote 122 This also ensured that none of the lessons of the flood was enshrined within disaster governance. Rather than subjecting itself to the kind of rigorous self-criticism (ziwo pipan) that it so often prescribed to political opponents, the party-state instead rewrote the history of the flood. This not only expunged thousands of lives from the record, but also precluded any chance that the flood might inspire the kind of ‘fundamental learning’ that Christian Pfister has identified as key to addressing the ultimate causes of disasters.Footnote 123 As a result, rather than seeking to respect and accommodate inevitable hydrological fluctuations, the government continued to do battle with the Yangzi. This culminated with the construction of the Three Gorges Dam. When this was completed in the first decade of the twenty-first century, the government seemed to have finally solved the problem of flooding in Hubei.Footnote 124 The millions displaced by this monumental engineering scheme were, it would seem, a price worth paying for hydraulic security.Footnote 125 Unfortunately, the declaration of victory in the war against water proved premature. During the summer of 2016, much of Hubei, including Wuhan, found itself once again under water. It would seem that residents of this long disaster-prone province are condemned to suffer flooding every time the Yangzi forgets that it has been vanquished.