Introduction

The Ancient Greek Language has a prominent role in several education systems in Europe, including Greece and Cyprus, where it is considered to be an integral course for a deeper understanding of European and ancient Greek civilisation. In the education systems of Greece and Cyprus, the course, particularly, aims at promoting the human, cultural and literary cultivation of students (Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, 2003, p. 78; Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports and Youth, 2010; Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, 2019, pp. 1–5, 19–23). The human perspective highlights students’ cognitive, sensory and emotional improvement, developing higher-level cognitive, metacognitive and emotional functions. The cultural dimension of the course introduces students to ancient Greek thought and the origins of Western culture, allowing a better understanding of the cultural present and recognisng individual and collective continuity. Furthermore, Ancient Greek texts, which offer aesthetic and literary value, enhance the literary education of students.

This paper argues that the above aims of the Ancient Greek course can be better achieved through the adoption of critical teaching. The principles of critical teaching can create the desired conditions for the cultivation of the human, cultural and literary development of students. Critical teaching is a form of teaching that actively involves students in the learning process, and enables them to formulate their own concepts, judgments, generalisations and interpretations (Bertrand, Reference Bertrand2003), cultivating in students higher-level cognitive, metacognitive and emotional functions (Krathwohl, Bloom & Masia, Reference Krathwohl, Bloom and Masia1964; Anderson & Krathwohl, Reference Anderson and Krathwohl2001). In addition, by adopting the principles of critical teaching, the course of the ancient Greek language can ensure the students’ active participation, an element which is in accordant with the Curricula of the Ancient Greek Language in Greece and Cyprus (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports and Youth, 2010; Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, 2019, p. 23).

Despite the need for the adoption of student-centred and group-centred methods of teaching as suggested by critical teaching, in Greek-speaking countries there are cases of teachers who, even today, teach the Ancient Greek Language in Lyceum through a teacher-centred approach in learning (Makris, Reference Makris2000; Tsiortas, Reference Tsiortas2008; Varmazis, Reference Varmazis2008; Markoglou, Reference Markoglou2017)Footnote 1. According to this teacher-centred approach, it is common for teachers to use the ancient Greek text as a tool for translation and grammatical and syntactic analysis, giving less emphasis to elements of content, conceptual and cultural understanding (Makris, Reference Makris2000, p. 579), which are promoted by critical teaching. This teacher's approach can be interpreted as:

a) a full adherence to the Attic teaching approach (a cultural and historical mentality) (Kakridis, Reference Kakridis1994; Makris, Reference Makris2000; Kazazis, Reference Kazazis and Christidis2001)

b) a lack of adequate pedagogical and didactic training of both future and in-service teachers (a structural problem) (Kazamias et al., Reference Kazamias, Kassotakis, Kladis, Kazamias and Kassotakis1996; Bilioni, Reference Bilioni2003; Kassotakis, Reference Kassotakis2010; Frydaki, Reference Frydaki2015; Bista, Kokkinos & Markoglou, Reference Bista, Kokkinos and Markoglou2016)

c) teachers' conviction that they help students better for National Exams (an institutional reason) (Tsiortas, Reference Tsiortas2008, p. 42; Varmazis, Reference Varmazis2008).

This paper suggests that it is imperative to replace the teacher-centred method of teaching the Ancient Greek language and to introduce teaching methods and practices which will incite students’ interest, involve them in the learning process and cultivate their social skills and relationships. The teaching of the Ancient Greek Language must allow students to work in the classroom according to their particular needs. This will be achieved once the teacher approaches the differing needs of the students with varied and hierarchical methods, processes and techniques which will help the teacher respond to the students’ diversified needs, which co-exist in mixed-ability classrooms (Tomlinson, Reference Tomlinson2000). In this effort a significant role is played by group-centred teaching, which is the evolution of student-centred teaching. In group-centred teaching students take the central part in the teaching through organised micro-groups and not as individuals, allowing that knowledge is a social entity and it is individually absorbed through cooperative interaction. Shor (Reference Shor1987), in fact, in a systematic analysis of critical teaching, which is in agreement with the educational theory of Freire, considers the cooperative learning, within organised sub-groups of students, as one of the key features of critical teaching. Cooperative learning is one part of the group-centred approach, during which students are organised into groups, learn to help each other, solve problems, communicate opinions and achieve a common goal. Students assume roles, collect information, investigate, evaluate, decide and present their work in written and oral form. As a result, encouraging interaction with other group members, thus improving their personal knowledge and their social and emotional skills (Johnson & Johnson, Reference Johnson and Johnson2009; Slavin, Reference Slavin2014).

Within this context, teachers should adopt cooperative teaching practices which cultivate learning incentives for students, encouraging them to essentially commit to the learning process, promoting their cognitive and emotional independence and developing their interaction, thus contributing at the same time to the creation of learning communities. Taking into consideration the needs of the educational community and school classroom, the current article presents a teaching proposal for the course of Ancient Greek language, emphasising the differentiation of the learning process. In particular, the procedure for teaching new knowledge through adopting basic principles of critical teaching and cooperative learning is described, focusing on the method of jigsaw-based cooperative learning as a teaching practice which promotes active student participation and group teaching.

Literature Review

Critical Teaching

Critical or Emancipatory Pedagogy is represented in the works of J. Dewey, P. Freire, H. Giroux, Μ.A. Vasquez and others (Bertrand, Reference Bertrand2003). According to the aforementioned thinkers, the main purpose of education is the development of the individual's ability to gain social freedom, self-determination and autonomous social action, which is dictated by the critical analysis (Grundy, Reference Grundy1987). The main educational aims of this approach are the manifestation of humanisation, critical conscientisation, and a problem-solving education system. Critical teaching is one part of this school of pedagogical thought and seeks to develop the emancipated, critical and active citizen and through it to change society and make it more democratic, fairer and more humanitarian. Through critical consciousness students are able to understand social problems and activate social action for the purpose of social emancipation. Critical teaching, also, seeks to invite both students and teachers to critically analyse political and social issues, as well as the consequences of social inequity (Nouri & Sajjadi, Reference Nouri and Sajjadi2014). In contrast to traditional teaching, critical teaching tries to actively involve students in the process of learning and aims at developing the function of critical and creative thinking. This requires a teaching based on dialogue that values social interaction, cooperation, authentic democracy, and self-actualisation. Within this context, teachers must ensure that the students are given the appropriate conditions for their development into autonomous and fulfilled personalities, through the effective teaching choices.

Cooperative Learning

Cooperative teaching is defined as a type of teaching which focuses on the students, working in internally heterogeneous groups, in order to achieve a common goal (Kagan, Reference Kagan1994). It refers to educational methods in which pairs or small groups of students work together to achieve this common goal. The aim of this cooperation is for them to maximize their personal knowledge through interaction with other members of the group. Through this process, students come out from a passive state and take an active role in the learning procedure, achieving performance improvements (Johnson & Johnson, Reference Johnson and Johnson2009; Slavin, Reference Slavin2014). This also reinforces students’ psychology, as, within the spirit of cooperation, students’ competition is reduced, criticism and rejection cease to dominate and students acquire positive self-perception and feel acceptance from the other members of the group. In addition, cooperative teaching contributes to the democratisation and socialisation of students, as they actively participate in decision-making through discourse and cooperative tasks. Cooperative learning releases students from passive listening, reinforces their initiative and develops their self-motivation. Students practise their critical capacity and are supported to develop their self-knowledge and self-criticism (Devi, Musthafa & Gustine, Reference Devi, Musthafa and Gustine2015), since at any given time they are asked to compare themselves with others and contribute to the group. Competition and egocentrism are limited and altruism, mutual respect and assistance, solidarity and assumption of personal and collective responsibility are encouraged. At the same time, students are provided with working techniques and methods. Finally, indifferent students are inspired to participate in the work done, monitor their own time and are, inevitably, led to self-improvement.

In addition, the cooperative teaching method helps teachers create a student-centred and group-centred learning environment, in which students will be able to achieve their best academic, affective and social-interpersonal development (Johnson & Johnson, Reference Johnson and Johnson2009; Slavin, Reference Slavin2014). Teachers provide all students with learning incentives and design group activities through which they can express questions, views and disagreements, discuss their ideas, criticise, explain and make decisions in groups. Moreover, teachers organise the class so that students take each other into consideration, assume responsibilities and learn how to listen, appreciate and assist each other, regardless of gender, nationality and performance of students. Using cooperative learning techniques, teachers utilise the students’ energy, steer it towards learning activities and help them develop from their core skills to solving complex issues (Slavin, Reference Slavin2014; Sharan, Reference Sharan2015; Duran, Flores & Miquel Reference Duran, Flores and Miquel2019). Cooperative teaching conveys responsibility and authority to students and allows them to work on their own to complete the project assigned to them. As a result, students are free to decide on the way in which they will complete their work, even if they make errors, and they are responsible for the final product.

Jigsaw Method

Nowadays, there are various cooperative methods and teaching techniques applied in various educational levels. This is confirmed by research data performed in order to develop more effective teaching methods in the classroom (Slavin, Reference Slavin2014; Sharan, Reference Sharan2015). One of these cooperative learning techniques is the jigsaw method, which emphasises cooperation and student support, reducing levels of competition in classroom. The technique of jigsaw is an alternative teaching method, based on cooperative learning. Group members need to cooperate with each other to achieve their learning goals, without using predetermined answers and solutions. Thus, they develop their social skills by seeking possible solutions and collecting information. Through this process, students modify their thoughts and views on given issues, delve into them, discuss and make decisions on the best possible solutions, planning their next steps.

Research has shown that the jigsaw method improves student performance at all educational levels (Killic, Reference Kilic2008; Sahin, 2010; Aronson & Patnoe, Reference Aronson and Patnoe2011; Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2012; Sharan, Reference Sharan2015). Research by Huang et al. (Reference Huang, Liao, Huang and Chen2014) showed that the jigsaw cooperative learning approach significantly assisted students with low and medium achievement. In addition, Honeychurch (Reference Honeychurch2012) performed research in which students from expert groups were asked to teach other students by posting their discussions online and then meeting up with the tutor to give presentations of their discussions to the class. As a result, students achieved higher grades in comparison to the conventional teaching method and the number of failures was reduced. At the same time, students reported that they would like their teacher to utilise this teaching method. Similar results were obtained in the research by Aronson and Patnoe (Reference Aronson and Patnoe2011) and Azmin (Reference Azmin2016), where it was ascertained that students taught using the jigsaw method had improved learning outcomes in comparison to others. Furthermore, the students stated that the jigsaw method helped enhance their self-esteem (Kilic, Reference Kilic2008) and improve their social skills (Johnson & Johnson, Reference Johnson and Johnson2009; Halimah & Sukmayadi, Reference Halimah and Sukmayadi2019).

The jigsaw classroom was developed in the 1970s by Elliot Aronson and his colleagues at the University of Texas. It is a method of cooperative learning, which requires cooperation in order to achieve the final product. Just like a puzzle, each piece (each student) is necessary for the production and full understanding of the final product. Initially, students are separated into mixed-ability home groups, in which an initial problem-solving question with reference to a common topic is set. Then, each student is asked to work on a different aspect of the common topic, creating new groups (expert groups). In each expert group, students work on the same aspect of the common topic. Then, they return to their home groups, explain and teach the other members of the group on the aspect of the topic they studied (Markoglou, Reference Markoglou2019) aiming to solve the initial problem (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Student movement during the jigsaw method

Stage 1

Students are included in four heterogeneous groups (home groups) (Figure 2), so in the beginning of the teaching process each student knows the group he/she is part of. The ideal group size is 3–5 individuals. The students’ previous knowledge is recalled and the initial problem is presented. Students are asked to exchange views on the topic studied. At this stage, the teacher must organise the classroom, compose groups, announce the groups’ learning goals, offer the new content and ask students to assume responsibilities, allocating the group task.

Figure 2. Home Groups

Stage 2

Expert groups are created (Figure 3), in which one student out of each home group becomes an expert for a specific part (sub-section) of the initial problem. In this phase, each student works on a particular part (sub-section) of his/her expert group, performs experimental activities, researches information in digital and printed sources, fills out worksheets etc. In addition, students plan the way in which they will teach their part to their classmates in home groups. At this stage, the teacher must encourage cooperative behaviour, confirm that students comprehend the teaching material and provide the necessary feedback.

Figure 3. Expert Groups

Stage 3

Students return to their home groups as experts (Figure 2) and are asked to present the results of their study and teach the part (sub-section) they studied to the other members of their home group, solving the initial problem together. At this stage, the teacher must evaluate the material presentation, the knowledge outcome and the group operation. Research shows that this stage is the basic advantage of this method emphasising the students’ assimilation of knowledge, while teaching their classmates. Next, the groups present their results to the entire classroom, and they are free to discuss them. Each group may be evaluated for its achievements and students may also be examined individually, in order to confirm the level of their knowledge (Aronson & Patnoe, Reference Aronson and Patnoe2011).

Thus, it is evident that the jigsaw technique encourages students’ participation in the classroom and increases the variety of learning experiences, teaching students both learning content and social skills (Perkins & Tagle, Reference Perkins, Tagle, Miller, Amsel, Kowalewski, Beins, Keith and Peden2011). It is a method that allows students to learn through interactive teaching, assimilating the knowledge of the subject for which their classmates are responsible. In this manner, they support their team and show interest in it (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Liao, Huang and Chen2014; Namaziandost et al., Reference Namaziandost and Pourhosein Gilakjani2020). Since each student in the work group is responsible for a small part of the learning material, which he/she teaches to his/her classmates, this places him/her in the centre of the knowledge creation process (Slavin, Reference Slavin2014; Tran, Reference Tran2016), developing his/her self-esteem and responsibility.

Ancient Greek Language in Greece and Cyprus

Public education in Greece and in Cyprus comprises four educational stages. The first stage is the pre-primary stage, which involves education for children up to the age of 6. The second stage is the primary stage, which lasts for six years (6–12 years old), followed by the secondary stage, which is separated into two sub-stages: the compulsory Gymnasium (non selective), which lasts three years (12–15 years old), and non-compulsory Lyceum (both selective and non selective), which lasts three years (15–18 years old). The fourth stage is Higher Education.

The subject of Ancient Greek is obligatory in the three Grades of the Gymnasium in both countries. From a total of four teaching hours per week which are devoted to it, two hours concern the teaching of the Ancient Greek Language from the Original Text, including translation, interpretive and grammatical and syntactic analysis of the text, while the other two hours are devoted to the teaching of the ancient Greek text in (modern Greek) translation. In the second case, in the first Grade of the Gymnasium students encounter Homer's Odyssey; in the second Grade Homer's Iliad and in the third Grade Euripides’ Eleni. In all three Grades of Ancient Greek Language in (Modern Greek) Translation, emphasis is placed on highlighting the appreciation, interpretive and cultural and literary value of the text (see Supplementary Table 1).

The syllabus at the Lyceum offers a variety of courses. Specifically, in the first Grade of Lyceum in Cyprus and in the second Grade in Greece students have to choose one Subject Orientation Group, which includes a default combination of courses and which leads to corresponding educational directions in the next years of Lyceum. In both countries, students who have chosen the Humanities Orientation Group have the possibility to further enhance their knowledge in Ancient Greek Language with additional teaching time.

In Greece the course of the Ancient Greek Language remains compulsory in the first and in the second Grade of Lyceum, through which students enrich their knowledge by studying Ancient Greek texts. At the first Grade of Lyceum, students are taught five hours per week, mainly Ancient Greek texts from Greek historiography (Xenophon and Thucydides). While in the second Grade, students have two hours per week from the Ancient Greek texts of Sophocles’ Antigone and Thucydides’ “Pericles’ Funeral Oration”, works with intense political and philosophical dimensions. At the same time, students, who have chosen the subjects of the Humanities Orientation Group, are taught Ancient Greek Language for an additional three hours per week. This consists of Lysias’ text, For Mantitheus and “Thematography”Footnote 2, during which teachers select Ancient Greek texts from Attic writers. This means a total number of five teaching hours per week. In the third Grade, students are prepared for the National Exams for Higher Education entrance. At this level, Ancient Greek Language is compulsory only for the students who have chosen the Humanities Orientation Group, which is offered six hours per week. Here, students are taught Ancient Greek texts from writers using Ancient Greek like Plato, Aristotle, Epictetus, Plutarch, Marcus Aurelius etc. and “Thematography” (See Supplementary Table 2).

In Cyprus, the course of Ancient Greek Language remains compulsory in the first and in the second Grade of Lyceum. At the first Grade of Lyceum, all students are taught two hours per week, mainly Ancient Greek texts from Greek historiography (Xenophon and Thucydides). At the same time, students from the Humanities Orientation Group, are taught Ancient Greek Language for an additional two hours per week, making four hours in total. At the second Grade, all students encounter Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex for one and a half hours per week. At the same Grade, students who have chosen the Humanities Orientation Group are taught Ancient Greek Language for an additional four hours per week: five and a half teaching hours in total. At this level, students approach Lysias’ text, For Mantitheus and “Thematography”, during which teachers select Ancient Greek texts from Attic writers. In the third Grade of Lyceum, where students prepare for the National Exams for Higher Education entrance, the Ancient Greek Language course is compulsory only for students of the Humanities Orientation Group and is taught for four hours per week. Here, students are taught Ancient Greek texts from Ancient Greek writers like Plato and Aristotle, and “Thematography” (see Supplementary Table 3).

Teaching Proposal

Lesson Plan Title: Teaching Ancient Greek through cooperation groups

Subject Matter: Ancient Greek Language

Subject: Structural-operational analysis of text and translation into the students’ native language

Teaching Unit: Xenophon Hellenica A (Ξενοφῶντος Ἑλληνικὰ A´), IV, 8–10

Student Classroom: 2nd or 3rd Grade of Lyceum (According to the knowledge level of participants)

Connection with National Curricula of Greece & Cyprus: The current lesson plan is fully compatible with the National Curriculum of Greece for Ancient Greek Language in Lyceum according to which students must be able to:

approach Ancient Greek texts in a structural-operational manner, examining their morphology, their syntax operation and the significance of the words in context,

produce translation using cooperative techniques,

approach knowledge in a cooperative manner in groups, using the discursive method and innovative actions,

use a dictionary (printed or digital) of Ancient Greek Language (Government Gazette 156/2015).

In addition, students must be able to:

identify the main terms of the sentence, noun attributes, adverb attributes

identify grammar and syntax forms… and translate into Modern Greek,

utilize the Grammar and Syntax textbooks,

perceive the structural syntactic elements of the Ancient Greek texts, determining differences in relation to the Modern Greek language with parallel differentiation between “understanding text” and “translating text” in Modern Greek language (Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, 2019).

The current teaching proposal is fully harmonised with the National Curriculum of Cyprus for the Ancient Greek Language in Lyceum, setting the following basic learning goals for students to:

process the Ancient Greek text in relation to the text's entirety, the communicational framework of text generation and the wider socially and culturally embedded context,

comprehend and interpret the Ancient Greek text with regard to its content… utilising elements of its form… and interpreting its content into Modern Greek,

cultivate their reading and communication skills,

interpret an Ancient Greek text, utilising its grammar and syntax elements (e.g. verbs, congruent and non-congruent attributes, participles, subordinate clauses etc.) (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports and Youth, 2010).

Recommended number of students: 20

Aim: For students to become acquainted with the Ancient Greek language through the structural-operational analysis of the text, perceiving the role of words in the text and utiliing them during the translation.

Goals:

Students must be able to-

With regard to knowledge:

identify the structure of the text, based on verbs, subjects, temporal attributes and causal relationships

recognise with structural-operational manner the terms of sentences in the Ancient Greek text and combine their operation in the translation of the text

translate the untaught Ancient Greek text into their native language (e.g. Modern Greek Language, English Language etc.)

With regard to skills:

cooperate in groups and interact with their classmates to achieve the group's common goal

utilise appropriate tools for their lifelong learning, such as the Syntax and Grammar textbooks and printed or/and digital dictionaryFootnote 3

With regard to attitudes:

practise their translation skills and be able to justify their translation choices, based on syntactic analysis

approach the language holistically, understanding that it is a system of co-dependent elements

cultivate their critical thinking, motivated by abstract reasoning for the interpretation of human action and the comprehension of historical/social context

Recommended teaching time: 90 minutes

Teaching Material:

For the implementation of the current lesson plan, the following are necessary:

(1) The extract of original Ancient Greek text: Xenophon Hellenica A (Ξενοφῶντος Ἑλληνικὰ A´), IV, 8–10 (Appendix 1)Footnote 4

(2) Expert Groups’ Auxiliary Material (Appendices 2, 3, 4, 5)

(3) The Grammar and Syntax TextbooksFootnote 5

(4) Ancient Greek Language Dictionary (Λεξικό της Αρχαίας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας) (in printed or digital form)

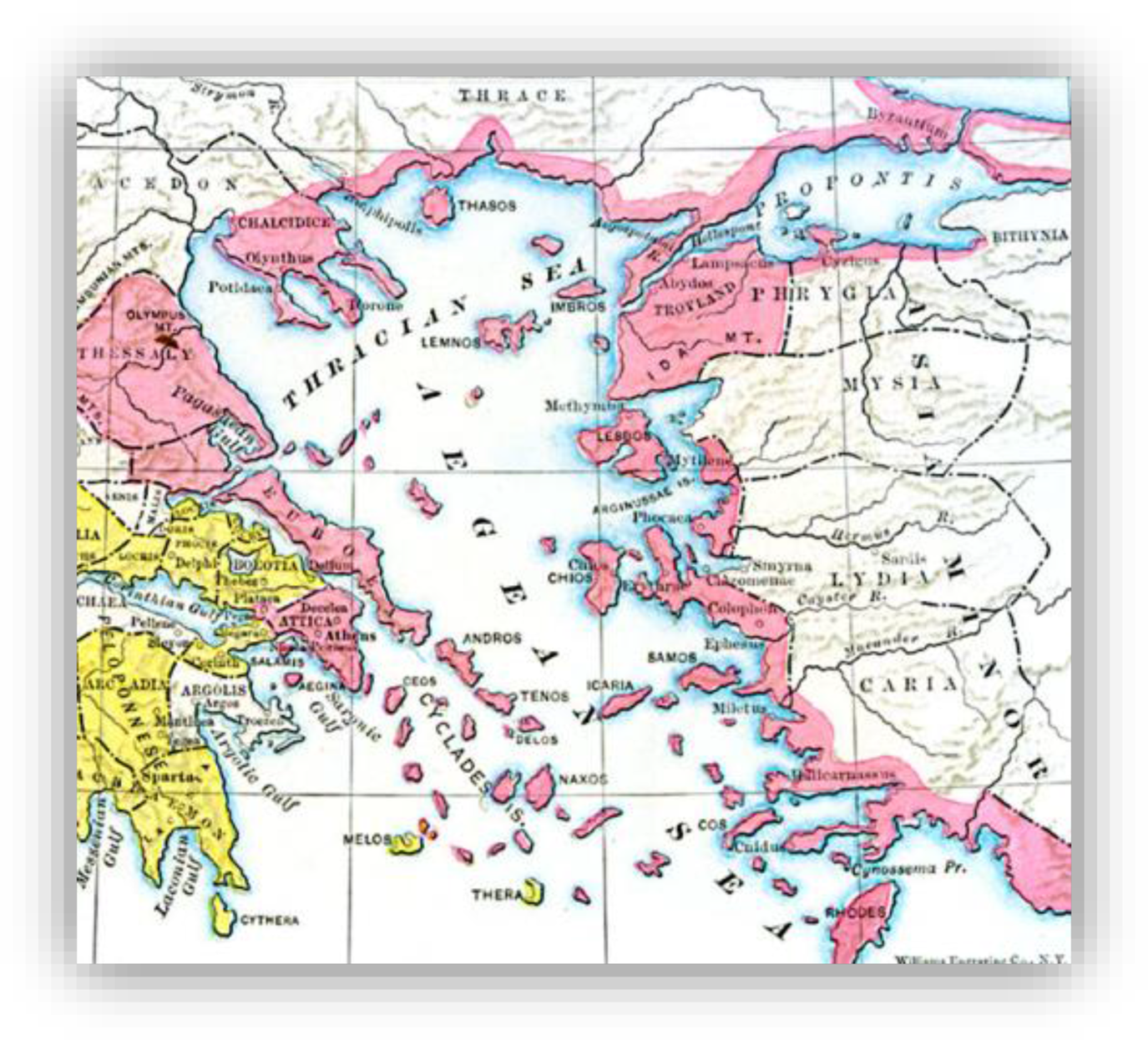

(5) Map: «Greece in the Peloponnesian War» (Figure 8).

Classroom potential and dynamics: The number of students, age, gender, relationships, methods of communication and the inclusion of students with special educational needs are factors which must be taken into consideration during lesson planning. For instance, a classroom of 20 students, four groups of five could be created, within which one student with special educational needs will be incorporated alongside one individual, thus creating a separate sub-group (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Classroom organization in home groups

Classroom structure: The classroom structure in this teaching proposal consists of four mixed-ability groups, with each containing five membersFootnote 6. Desks have been arranged in four groups and are marked by the colour of the envelope placed on them -red, yellow, blue and green. When students enter the classroom, the teacher offers them bracelets with different colours -red, yellow, green, blue- which bear a number on one side and the student's name on the other; in this way each student knows the group in which he/she will be included (home and expert group) (Figures 4, 5 and 7).

Figure 5. Home Groups – Material for the Students

Continuing the teaching process, students are separated into expert groups (Figures 4 and 6) allowing those with special educational needs to create a “group” with another classmate within the group (see different colours in Figure 4). At the same time, the teacher may use the cards to appoint a certain role to each student, e.g. Dictionary Manager (Responsible for the Dictionary) (DM), Grammar & Syntax Manager (GSM), Materials Manager (MM), Group Leader (GL), Timekeeper (T), Recorder (R), Group Speaker (GS), Checker (C) etc.

Figure 6. Classroom organisation in expert groups

Finally, students return to their home groups, in order to offer assistance to their classmates with regard to the knowledge they obtained during the previous stage (Figure 4).

Teaching Stages - Teaching Process: First Teaching Stage: Motivation of students’ interest (Orientation-Brainstorming)-(Home Groups) (5 minutes)

During the first teaching stage, the teacher has separated students into heterogeneous home groups (Figures 2 and 4) and aims to incite their interest, recalling their previous knowledge, using questions such as the following: “What do you know about Xenophon?”, “Through your knowledge from previous classes, what do you know about the historical/social framework of the era in which he lived?”, “What forms of text did he produce?”, “What is historiography?”, “Do you remember any of his work?”.

Once students state some basic information, the text is presented on the interactive board (Xenophon Hellenica A [Ξενοφῶντος Ἑλληνικὰ A´], IV, 8–10) (Supplementary Appendix 1) and the teacher asks them to express their hypotheses with regard to the topic, assisting with the following instruction: “Remember the era in which he lived and the historical fact that took place at this time”. Students express their hypotheses and the teacher listens carefully and records them on the board (Brainstorming technique), without confirming or rejecting any of them.

Second Teaching Stage: Text subject- Introduction in the historical/social context (Offer-Presenting new knowledge) (Home Groups) (15 minutes)

In the next stage, the teacher hands out the untaught Ancient Greek text (Supplementary Appendix 1) to the students and proceeds to a loud and careful reading. Then he/she asks students to read it alone for 1–2 minutes. Completing the reading, he/she asks the students whether their original hypotheses were confirmed or not and asks them to state the subject of the text. Encouraged by the students’ responses, the teacher reminds them of the information with regard to the text's historical/social context:

“Xenophon was born in the municipality of Erhia, Attica in 431 BC and died in 355–4 BC. He lived in Athens during the troubled years of the Peloponnesian War until the defeat in 404 BC, the rise of the Thirty Tyrants in power and the restoration of democracy in 403 BC. His historical works include Hellenica, in which he narrates the history of Greek cities from 411 BC, from the point where Thucydides stopped the history of the Peloponnesian War, until 362 BC. In particular, the first two books include events from 411 BC to the defeat and surrendering of Athens in 404 BC. In addition, he refers to the conflicts between Athenians (Alcibiades) and Spartans in Ellispontos and the eastern Aegean, with the successes mostly of the Athenians (411–408 BC) and with reference to the return of Alcibiades in Athens (408 BC)”.

At this point, it is explained to the students that during the next stage they will be separated into expert groups, with each “expert” group assuming further processing of certain parts of the text. Thus, once they return to their home groups they can help their classmates in the text's syntax processing and translation, which contributes to the final teaching goal.

Third Teaching Stage: Processing (55 minutes)

a. Expert Groups (25 minutes)

Proceeding to the learning and teaching process, the teacher asks the students to notice the number on their bracelets and proceed to the respective expert group (Figures 2, 6 and 7). He/she then hands out the respective educational material (Supplementary Appendices 2, 3, 4, 5) per group (see the table below).

Figure 7. Expert Groups – Material for the Students

Table 1. Differentiation of expert groups by subject

Once the material has been handed out to students, the teacher guides them by offering the following instruction:

“Working in expert groups, try to recall your knowledge and work on the syntactic and grammatical elements which are requested. Then, endeavour a first translation of the respective sections into your native language. The teaching process may be facilitated with the use of the Syntax and Grammar textbooks, available to each group, which you can consult for further clarifications. Please remember that you can also use the Dictionary. Ask the Dictionary Manager for help, in case of difficulties”.

Throughout the process, the teacher provides clarifications, corrections and feedback and assists the learning group task, emphasising the importance of the words’ operation in the text, for its comprehension, interpretation and translation. With this in mind, he/she also helps the process, asking questions such as the following:

For Group A: “Who is the protagonist?”, “Which other protagonists does Xenophon refer to?”, “Who is acting here?”, “Where is the action applied?”, “What is the case of the subject and object? Why?”, “Why is a noun attributed with a property through the predicate?” etc.

For Group B: “Is the protagonist alone or with others?”, “Where did he head to?”, “Where had he started from?”, “What do prepositions σύν, εἰς, ἐπὶ reveal?”, “What was the status of Thasos? What was it due to?”, “What do you know about the agent? How is it introduced and expressed?” etc.

For Group C: “What words determine the subject/or object?”, “What does this particular case show?”, “Why is a property attributed to a noun through the noun attribute?”, “What property does it attribute to the word? A permanent or transient one?”, “Which other word shares the same case?”, “What does the attribute reveal with this word? (e.g. possession, cause, value etc.)” etc.

For Group D: “Which word determines the noun?”, “Why is the participle introduced with this case?”, “What does this word reveal? (e.g., location, time, manner etc.)”, “Why did you characterise this participle as temporal? What helped you understand it?”, “When did it take place? Which was the previous action? What word shows this?”, “Did this action happen before or after the other (action)?” etc.

For All Groups: “What verb does this word come from? What does it mean?”, “How would you translate this word or phrase? Could it be translated in an alternative way as well?”, “Do you know any etymologically-related words?”, “What is the significance of the word in the text?”, “Please see the Grammar and Syntax textbooks for more information”, “Remember to study the worksheets which are handed out (Supplementary Appendices 2, 3, 4, 5)”, “Search for the word root in the dictionary” etc.

At this stage, the goal is for students to highlight core points of the text, having completed a first processing and translation of certain sections, according to their abilities and needs, facilitating the processing of the entire text in the next teaching stage. In this phase, students discuss, listen to the opinions of other group members, offer their own opinions and respond to questions. In addition, they try to foresee the questions of the home group's other members and discuss possible answers. This ensures a positive co-dependence among the group members.

b. Return to Home Groups (30 minutes)

Once the students’ work in expert groups is completed, they are asked, as experts, to return to their home groups (Figure 4) and process the text in its entirety. At this point, the teacher encourages students to work as a team and after carefully re-reading the entire text, to perform syntax processing and translate it into their native language.

Further on along the teaching practice, students-experts are asked to help and teach other members of the group the points assimilated during the previous stage. During this stage, they are asked to utilise the dictionary and Grammar and Syntax textbooks, as well as the auxiliary material (Supplementary Appendices 2, 3, 4, 5) where it is necessary. The teacher facilitates the process by offering the following instruction:

“Separate the text's sentences and proceed first with the basic terms and then the more complex words and phrases. Discuss with your group the answers you found in the Expert Groups”.

Students are encouraged to comprehend the structural-operational approach of the Ancient Greek text and its necessity during its translation. It is important for them to realise that the comprehension of a word's meaning cannot be exhausted in the simple knowledge of a mere translation, but requires the student's endeavour to seek its position and operation within the text and thus determine its exact content. Students must understand the significance of morphology, syntax analysis and meaning of the words within the context (not independently) and to translate the text, as well as the entirety of the language which consists of co-dependent elements. Throughout the process, the teacher must remind, organise, offer advice and answer any questions, taking into consideration the significance of team work and participation in all teaching stages, avoiding (as much as possible) any interventions which discourage the students’ independence.

Fourth Teaching Stage: Group outcomes announcement- Evaluation (15 minutes)

Once the groups’ tasks are completed and in order for the teacher to confirm that all students worked and understood the subject, he/she must encourage groups to present a part of their task, in order to compare their answers with the other groups. In summary, the teacher hands out a map to all groups, in printed form (Figure 8). Group members are asked to design the course taken by Alcibiades, Thrasybulus and Thrasyllus, according to the text. Planning out their courses will help students focus, process and briefly present the basic points of the Ancient Greek text.

Figure 8. Greece in the Peloponnesian War

The current teaching proposal includes a constant and formative evaluation, during which information necessary for the achievement of the course's goals will be collected. The teacher applies the cooperative jigsaw method and seeks to create a supportive environment for the students’ motivation/response, illustrating their knowledge and skills in the framework of group work. The teacher also aims to improve both themselves and the students, to enhance teaching effectiveness. In addition, special emphasis is given to the students’ group work, which contributes to their familiarisation with the Ancient Greek texts and the development of their self-motivation, offers them opportunities for active participation and free expression, enhances their interest, develops their personal relationships and promotes cooperation and discourse.

Conclusion

In the framework of teacher training, the current teaching proposal was presented to a class of 2nd Grade Lyceum students, who have chosen subjects of the Humanities Orientation Group. The results seemed to be encouraging, since students successfully completed the activities, achieved the learning goals and participated with unyielding interest throughout the teaching process. In addition, participating teachers noticed that the jigsaw method helped both stronger students, who assumed the Group Leader role, and average and weaker students, who seemed to develop their self-confidence, increasing their participation in the task. Furthermore, offering the new knowledge through interactive learning seemed to significantly improve the social and emotional skills of all students (critical teaching). With regard to drawbacks, it could be noted that very good organisation and methodical work is required on behalf of the teacher, who must be very well acquainted with the students, in order to effectively organise the composition of groups; all of which is extremely time-consuming.

In conclusion, the cooperative teaching method is a model of social form, emphasising the active involvement and participation of students in the learning process, fulfilling the criterion of teaching differentiation. At the same time, teacher-centred approach is replaced by group-centred learning and classmates are converted from competitors to partners and assistants, promoting higher-level cognitive, metacognitive and emotional functions. Thus, the educational system has to support teachers in the application of cooperative teaching methods in classrooms; offering them constant professional development both during and after undergraduate studies and, thereby, creating favourable learning environments for future teachers to develop cooperative learning experiences (Ferguson-Patrick, Reference Ferguson-Patrick2012).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2058631021000441.