The study of inequality and punishment has been a major enterprise in the law and society tradition. The focus of this research, though, has changed over time in the wake of major demographic shifts. Historically, the purview of scholarship has been limited to the dichotomy between blacks and whites. However, against the backdrop of decades of increased immigration from Latin America, more recent research argues for a concerted emphasis on Hispanic ethnicity for understanding contemporary legal stratification (Reference SpohnSpohn 2000; Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier & Demuth 2000, Reference Steffensmeier and Demuth2001). Drawing from the minority threat perspective (Reference BlalockBlalock 1967), this trend plays a prominent role in contemporary theoretical accounts of criminal punishment. For example, Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier and Demuth (2000: 710) argue “the specific social and historical context involving Hispanic Americans, particularly their recent high levels of immigration, exacerbates perceptions of their cultural dissimilarity and the ‘threat’ they pose” which in turn “contribute[s] to their harsher treatment in criminal courts.” Using federal court data, the authors show that Hispanics receive more severe punishment than both white and black defendants. Subsequent research in this vein also suggests that Hispanics are now the most disadvantaged group within the courts (Reference Doerner and DemuthDoerner & Demuth 2009; Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier & Demuth 2001).

However, the body of research noting the shifting axes of legal inequality toward Hispanics has yet to fully engage the role of citizenship status. This is likely consequential given that 26 percent of all Hispanics in the United States are noncitizens and 80 percent of Hispanics punished in U.S. federal courts over the past two decades lacked U.S. citizenship.Footnote 1 Furthermore, the increased prosecution and punishment of noncitizens coincide with broader trends of enhanced social control of immigrants (Reference StumpfStumpf 2006; Reference WelchWelch 2003), leading some to suggest that the border now represents the new criminal justice frontier (Reference SimonSimon 1998). According to Reference Bosworth and KaufmanBosworth and Kaufman (2011: 431), for instance, those who lack U.S. citizenship (regardless of race or ethnicity) have become the “next and newest enemy” in the U.S. war on crime.

Thus, one must account for changes in the social control of non-U.S. citizens in recent decades to understand the significance of Hispanic ethnicity on criminal punishment. Moreover, if the shifting demography of criminal offenders correlates with changes in legal stratification, any changes over time in the punishment of Hispanics will be inextricably linked to changes in the treatment of noncitizens. Though recent scholarship has begun to examine the role of citizenship at criminal sentencing (Reference DemuthDemuth 2002; Wolfe, Pyrooz, & Reference Wolfe, Pyrooz and SpohnSpohn 2011; Reference Wu and DeLoneWu & Delone 2012), extant research has not fully examined the long-term punishment trends for Hispanic and non-U.S. citizen offenders. As a result, important questions remain regarding the changing nature of legal inequality in the United States. Has the Hispanic sentencing “penalty” emerged over the past two decades, or the citizenship “penalty?”

The comparative paucity of empirical work on citizenship and punishment is symptomatic of a more general lack of focus in sociolegal inquiry beyond those markers that traditionally stratify within society. As Reference Bosworth and KaufmanBosworth and Kaufman (2011: 430) note, “most sociologists of punishment and imprisonment remain wedded to a nationalist vision of state control, one unaffected by growing transnational flows and mobility.” Though citizenship is not a legally relevant sentencing criterion under U.S. law, the current study builds on recent sentencing research and argues for the theoretical and empirical importance of examining the punishment of nonstate members.

Using U.S. federal court information from 1992 to 2009, this study offers one of the first systematic investigations of the long-term trends in sentencing disparities for noncitizen offenders across diverse court contexts. Investigating the social context of criminal sanctions has been a major advancement in punishment research (Reference KauttKautt 2002; Reference JohnsonJohnson 2006; Reference UlmerUlmer 2012; Reference Ulmer and JohnsonUlmer & Johnson 2004), yet there are comparatively few studies on the role of social and temporal contexts. This is a notable gap as previous work suggests that punishment disparities likely change over time just as they vary across courts (Reference Peterson and HaganPeterson & Hagan 1984; Reference Thomson and ZingraffThomson & Zingraff 1981). Using multilevel modeling techniques to nest individuals within time period and judicial district, this study simultaneously incorporates temporal trends over nearly two decades with district-level contextual measures to examine how the district court context conditions the punishment of non-U.S. citizens over time.

Drawing from the single largest legal system in the United States (the federal courts),Footnote 2 this study is well suited to investigate (1) the punishment consequences of citizenship status, (2) how the sentencing of noncitizens changed over the past two decades, (3) whether these changes alter the trends for Hispanics, and (4) whether these temporal trends are conditioned by the district in which they occurred. In doing so, this research speaks to a number of salient themes germane to the study of legal inequality. Most notably, how have the axes of legal stratification shifted in the wake of increasing international migration? While prior work points to the increased salience of Hispanic ethnicity, this study seeks to broaden the current discourse on legal inequality beyond race and ethnicity by clarifying the theoretical linkages between citizenship and criminal court decisionmaking.

Race/Ethnicity, Citizenship, and Punishment

Racial disparities in criminal punishment are one of the most well-researched topics in the study of legal inequality (see Reference MitchellMitchell 2005 for review) and the weight of the evidence suggests black offenders are disadvantaged at sentencing relative to similarly situated whites, though the effect of race is “often subtle, indirect, and typically small relative to legal considerations” such as criminal history and crime severity (Reference Johnson and BetsingerJohnson & Betsinger 2009: 1048).

Responding to the rapid influx of Latin American immigrants, punishment research has turned toward the role of Hispanic ethnicity at sentencing in recent decades (Reference AlbonettiAlbonetti 2002; Reference JohnsonJohnson 2003; Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier & Demuth 2000, Reference Steffensmeier and Demuth2001). Studies from both state and federal courts suggest that Hispanic offenders are punished more severely than whites (Reference AlbonettiAlbonetti 1997; Reference LaFreeLaFree 1985) and may have even replaced African Americans as the most disadvantaged group at sentencing (Reference Doerner and DemuthDoerner & Demuth 2009; Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier & Demuth 2000, Reference Steffensmeier and Demuth2001). However, work emphasizing the importance of Hispanic ethnicity has paid limited attention to the role of citizenship. In state court studies, this is partially a reflection of data limitations as information on citizenship is rarely if ever collected. In federal courts, however, this information is readily available but often underutilized. Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier and Demuth (2000) and Reference Doerner and DemuthDoerner and Demuth (2009), for instance, simply remove noncitizens from their analyses.Footnote 3 If noncitizens are punished more harshly than U.S. citizens, this raises the interesting possibility that because many Hispanic offenders are also non-U.S. citizens, the Hispanic “penalty” may be overstated in state court studies and incomplete in federal court research.

That the vast sentencing literature tells us much about racial/ethnic inequality but comparatively less about citizenship largely reflects the punishment fields' focus on traditional markers of stratification (e.g., race, class, gender). Even research arguing for a more expansive view of sociolegal inequality largely remains in the purview of racial/ethnic relations, for example, by focusing on Asians or Native Americans (Reference Alvarez and BachmanAlvarez & Bachman 1996; Reference Johnson and BetsingerJohnson & Betsinger 2009). As international migration increases and nonstate members become a growing and permanent presence in U.S. society, this approach may be untenable and calls for research to look beyond racial/ethnic legal stratification.

As immigration has become an increasingly contentious social issue, recent studies have taken up this call by investigating the effect of citizenship at sentencing (Reference DemuthDemuth 2002; Reference Hartley and ArmendarizHartley & Armendariz 2011; Wolfe, Pyrooz, & Reference Wolfe, Pyrooz and SpohnSpohn 2011). However, the findings from this research have been inconsistent. One line of work suggests no sentencing differences between citizen and noncitizen offenders' net of controls for guideline-related factors and offense type (Reference Everett and WojtkiewiczEverett & Wojtkiewicz 2002; Reference Kautt and SpohnKautt & Spohn 2002). Another body of work, however, finds that noncitizens are treated more harshly in federal courts even after accounting for criminal history, offense severity, and other legally relevant factors (Reference AlbonettiAlbonetti 2002; Reference Hartley and ArmendarizHartley & Armendariz 2011; Reference MustardMustard 2001). A third body of work balances these conclusions and suggests a more nuanced relationship between citizenship and sentencing. Reference DemuthDemuth (2002), for instance, finds that legal and illegal aliens are more likely to be incarcerated, but finds no sentence length differences (see also Reference AlbonettiAlbonetti 1997). Reference Wolfe, Pyrooz and SpohnWolfe, Pyrooz, and Spohn (2011) and Reference Wu and DeLoneWu and DeLone (2012) also find that noncitizens are disadvantaged at incarceration, but actually receive shorter prison terms.

Various factors may explain these mixed findings. Studies vary considerably in their methodological approaches and research purposes (Reference Wu and DeLoneWu & DeLone 2012), such as focusing on select districts (e.g., border districts), analyzing specific offense types (e.g., drugs), or by treating citizenship as a control variable (Reference UlmerUlmer 2005). Another plausible reason for these different findings is that sentencing disparities may change over time and scholars often rely on samples from different years. Reference MustardMustard (2001), for instance, uses data from 1991 to 1994 while Reference Wu and DeLoneWu and Delone (2012) use data from 2006 to 2008. Research investigating temporal trends in sentencing disparities demonstrates that legal inequality often varies over time and across jurisdictions, suggesting that punishment practices track temporal and demographic shifts (Reference Fischman and SchanzenbachFischman & Schanzenbach 2012; Reference Koons-WittKoons-Witt 2002; Reference Kramer and UlmerKramer & Ulmer 2009; Reference Miethe and MooreMiethe & Moore 1985; Reference Pruit and WilsonPruit & Wilson 1983; Reference Stolzenberg and D'AlessioStolzenberg & D'Alessio 1994; Reference WooldredgeWooldredge 2009). However, research has yet to investigate the interactions between both time and place to understand how court contexts may condition the trends in legal inequality. Perhaps most important for the current study, little research has investigated the long-term trends in citizenship disparities. As a result, the literature lacks a systematic assessment of the punishment consequences for non-U.S. citizens over the past two decades, a period in which the noncitizen population nearly doubled and is now at its largest point in American history.

Given the divergent conclusions in extant research, further inquiry is needed. This is especially the case given the changing social contexts surrounding contemporary immigration and the stepped-up social control of immigrants.

Citizenship and Social Control

Recent decades have witnessed a blurring of the boundaries between immigration and crime control (Reference MillerMiller 2005) and legal scholars have coined the term “crimmigration” to capture the importation of criminal justice strategies into migration policy (Reference StumpfStumpf 2006). Reference Bosworth and KaufmanBosworth and Kaufman (2011: 440) describe this nexus as the process through which “both the imagery and the actual mechanisms of criminal justice—such as the police and the prison—are adopted for the purpose of border control,” and point to several policy and legal developments to underscore this convergence. These include increased border security, expanding criminal prosecutions for immigrant offenders, and escalations in criminal deportations (Reference EllermannEllermann 2009). As an example, Congress has taken unprecedented steps toward revising U.S. immigration laws to deal with criminal aliens in recent decades in response to the perceived link between immigration and increased crime and drug problems (Reference Hagan, Levi and DinovitzerHagan, Levi, & Dinovitzer 2008; Yates, Collins, & Reference Yates, Collins and ChinChin 2005). Most prominent among these is the expansion and retroactive application of the “aggravated felon” classification—which specifies the types of crimes for which aliens can be deported—to include relatively minor drug offenses (Reference MillerMiller 2005).

The convergence between crime and immigration policy has resulted in the dramatic increase of noncitizens under state control. Some statistics are illustrative of the scale and growth of this punitive turn. In 1980, a total of 391 criminal aliens were deported from the United States (Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2004: cited by King, Massoglia, & Reference King, Massoglia and UggenUggen 2012: 787). By 2009, this increased to over 130,000 (Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics 2011). The trends in the courts are equally dramatic. Between 1992 and 2009, noncitizens increased from roughly 8,000 offenders, representing 22 percent of the federal docket, to over 34,000 offenders and constituting nearly half of all convicted cases.

These trends underscore the increasing importance of citizenship for sociolegal studies. In this article, I extend this body of work by going beyond political and criminal justice policies to another area of legal research: criminal punishment.

The Links between Citizenship and Court Decisionmaking

Despite being one of the primary units of social organization (Reference BrubakerBrubaker 1992), the study of citizenship has not traditionally been a major focus of sociolegal research or sociological inquiry more generally. Only recently have scholars begun investigating the role and consequences of citizenship across a variety of social domains (Reference Bloemraad, Korteweg and YurdakulBloemraad, Korteweg, & Yurdakul 2008).

One area focuses on the function of citizenship. According to Reference BrubakerBrubaker (1992) and Reference WimmerWimmer (2002), citizenship can be best characterized as a mechanism of stratification and social closure; for while it is internally inclusive, it is externally exclusive. By defining membership to the state, citizenship confers rights and privileges, and distributes life opportunities (Reference MarshallMarshall 1964; Reference SmithSmith 1997). Recent research noting the disadvantages faced by noncitizens and undocumented immigrants in the labor market (Reference Hall, Greenman and FarkasHall, Greenman, & Farkas 2010), education system (Reference Suárez-OrozcoSuárez-Orozco et al. 2011), and during the transition to adulthood (Reference GonzalesGonzales 2011) are consistent with this view. With over 22 million non-U.S. citizens residing in the United States (Reference Passel and CohnPassel & Cohn 2009), some scholars suggest that citizenship and legal status are now central axes of stratification in American society (Reference MasseyMassey 2007). As a legal distinction, this work suggests citizenship is a powerful mechanism of stratification, as formal exclusion interacts and amplifies other social inequalities (Reference CalavitaCalavita 2005; Reference GlennGlenn 2011).

A second area focuses on the development of distinct and mutually exclusive nation states. While states are often characterized as territorial units, modern nation states involve larger cultural, normative, and symbolic debates about who has legitimate claim to the state (Reference WimmerWimmer 2002: ch. 4). A central feature of the modern nation state involves determining membership to the nation through citizenship. According to Reference WimmerWimmer (2002), the boundaries of membership are determined through cultural compromise, which centers around the “imagined community” (Reference AndersonAnderson 1983) of the nation—a political community grounded on common origin and historical experience. This cultural compromise can be understood as a consensus over the validity of collective norms, social classifications, and world-view patterns that separate the homogenous domestic realm of the nation state (i.e., the collective “us”) from the heterogeneous external one (the collective “them”) (Reference WimmerWimmer 2002).

Conceptualizing citizenship as an outcome of cultural compromise and a mechanism of stratification has important implications for the study of legal inequality. First, as a mechanism of stratification, this places citizenship squarely within the gamut of scholarship on inequality and punishment. An underlying premise of this research suggests that one's position in the social structure has implications for treatment within the legal system because the socially marginal may (1) lack the political resources and ability to resist negative labels (Reference Chambliss and SeidmanChambliss & Seidman 1971; Reference TurkTurk 1969), (2) threaten the economic interests of powerful groups (Reference LoflandLofland 1969), or (3) be perceived as culturally dissimilar and dangerous (Liska, Logan, & Reference Liska, Logan and BellairBellair 1998; Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier & Demuth 2000).

Though largely applied to minorities and the poor, each of these perspectives is equally relevant to the case of noncitizens. First, it is hard to imagine a group with less political power, as noncitizens are barred from voting in most elections (Reference TiendaTienda 2002), thus limiting their ability to raise political concerns about unfair legal practices. Second, the economic threat of immigrants has played a prominent role in public and political discourse. For example, the discourse surrounding Proposition 187 passed in 1994 in California—which barred undocumented immigrants from attending public schools and receiving nonemergency health care—focused almost entirely on the perceived financial burden of illegal immigration (Reference King, Massoglia and UggenKing, Massoglia, & Uggen 2012). Additional factors compound the status of noncitizens, including perceptions of criminal dangerousness (Reference WangWang 2012) and perceived threats to the racial, linguistic, and cultural integrity of the United States (Reference HuntingtonHuntington 2004).

According to the focal concerns perspective (Reference Steffensmeier, Ulmer and KramerSteffensmeier, Ulmer, & Kramer 1998), these factors may influence the punishment of noncitizens through the consideration of (1) the blameworthiness of the defendant, (2) their perceived dangerousness to the community, and (3) the practical constraints on judges' punishment decisions. The focal concerns perspective stresses that because the risk and seriousness of recidivism are never fully predictable and defendant character cannot be known entirely, court actors may make assessments of dangerousness, blameworthiness, and the salience of relevant practical constraints and consequences partially based on attributions linked to defendant characteristics such as their gender, race, or perhaps citizenship (Reference Ulmer and JohnsonUlmer & Johnson 2004).

Based on this framework, three influences are likely particularly relevant to the sentencing of noncitizens. First, judges face unique practical considerations when punishing non-U.S. citizens in that most alternative sanctions (e.g., rehabilitation, drug treatment) are not available to noncitizens, making incarceration sentences more likely. In addition, noncitizens are likely to face deportation after adjudication and in the case that a deportation detainer has been issued by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, noncitizen offenders are likely to be detained prior to final adjudication and judges may feel limited to consider only imprisonment.

Second, focal concerns' emphasis on the role of social marginalization in attributing culpability and dangerousness is likely germane to non-U.S. citizens. This argument shares theoretical roots with earlier work on social inequality and legal outcomes. In his theories of law and social control, Reference BlackBlack (1976: 44) suggests “it is possible to measure the distance between a citizen and law itself” and that “those who are marginal to social life are more likely to be blamed. In general, their conduct is more likely to be defined as deviant, and whatever they do is more serious” (Reference BlackBlack 1976: 59). Conceptualizing citizenship as a measure of stratification with profound implications for one's location in the social structure, it follows that those without U.S. citizenship will be viewed as more deviant and thus more deserving of harsh punishment.

Third, both Black's theory of law and the focal concerns suggest those perceived as culturally dissimilar will be viewed as more deserving of harsher punishment. According to Reference BlackBlack (1976), legal officials are more conciliatory toward those viewed as cultural “insiders” and more punitive toward those who are not (i.e., “outsiders”). Thus, viewing citizenship as an outcome of cultural compromise may have implications for the punishment of non-U.S. citizens. It follows that those who fall outside the national community will be viewed by definition as culturally dissimilar (i.e., not one of “us”). As a salient measure of cultural distance between legal officials and defendants, this perspective suggests noncitizens will be perceived as particularly blameworthy and thus more likely to receive severe punishments. Additionally, membership in the national community should be more relevant for gauging cultural distance than race or ethnicity alone. This suggests that citizenship may be more consequential than racial/ethnic distinctions in determining punishment outcomes. If this is the case, any increasing trends in Hispanic disparity will be considerably diminished once the trends in citizenship disparities are taken into account.

Taken together with the “crimmigration” literature, the effects of citizenship should be particularly pronounced over the past two decades as immigration has become a contentious social issue (Pew Hispanic Center 2006) and international migration has been perceived to be linked to crime and terrorism (Reference Givens, Freeman and L. LealGivens, Freeman, & Leal 2009). Moreover, just as previous research predicts that the increase of Hispanics may have resulted in greater ethnic disparities, it is likely that the dramatic influx of noncitizens into federal courts has induced threat responses along cleavages of national identity and belonging. Against this backdrop, legal officials may increasingly view non-U.S. citizens as deserving of harsher punishment over this period, suggesting that citizenship may matter more over time. This prediction is rooted in the classic work of Reference BlalockBlalock (1967) and Reference BlumerBlumer (1958) and contemporary extensions on “racialized” threat in the punishment literature (Reference Ulmer and JohnsonUlmer & Johnson 2004), which suggests that court actors may perceive minority offenders as especially threatening and dangerous when minority populations are increasing.

However, the minority threat perspective suggests the effect of citizenship will also vary across districts experiencing different demographic shifts. In the District of New Mexico, for example, noncitizens represented 87 percent of the docket in 2009, up from only 33 percent in 1992. But in the Eastern District of New York, noncitizens went from 57 percent down to 40 percent over this period. In line with the core tenets of the minority threat perspective, it is likely that any citizenship “penalty” will be exacerbated in districts where the relative population of noncitizens has increased. Extending this argument longitudinally, any increase in the citizenship “penalty” over time should be greatest in districts with an increasing noncitizen population.

Data and Methods

The primary data for this analysis come from the U.S. Sentencing Commission (USSC) for fiscal years 1992–2009. As part of the Sentencing Reform Act, Congress required the USSC to collect information on all cases and offenders punished in U.S. federal courts. The USSC data are a rich source of detailed information on the offense and legal characteristics associated with a case, such as offense type and severity, criminal history, and number of convictions, as well as characteristics of the defendants. These detailed measures provide an extensive and comprehensive set of controls to assess the long-term trends in citizenship punishment disparities. It is important to note that citizenship is not a legally relevant punishment criterion in federal courts and the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently ruled that noncitizens are afforded due process protections in criminal courts under the Constitution Reference Rubio-Marin(Rubio-Marin 2000). As legal scholar Reference ColeDavid Cole (2003: 381) puts it, “the Constitution extends fundamental protections of due process … and equal protection to all persons subject to our laws, without regard to citizenship.”

I follow previous research and exclude districts in Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, and the North Mariana Islands, restricting the universe to those districts that are in the United States (Reference Ulmer, Light and KramerUlmer, Light, & Kramer 2011). I also limit the analysis to nonimmigration offenders because U.S. citizens are not at risk to be sentenced for the bulk immigration crimes, as over three quarters of immigration offenses are “unlawfully entering or remaining in the U.S.” (e.g., there is no citizen comparison group).Footnote 4

Dependent Variables

Prior research indicates sentencing decisions can be divided into two distinct outcomes: whether to incarcerate and how long to incarcerate (Reference King, Johnson and McGeeverKing, Johnson, & McGeever 2010; Reference Steffensmeier and DemuthSteffensmeier & Demuth 2000; Reference Ulmer and JohnsonUlmer & Johnson 2004). This study follows this convention.Footnote 5 Incarceration is a dichotomous measure for whether an offender was sentenced to prison (1 = yes). I use the logged number of months of incarceration (capped at 470) in all sentence length analyses because the actual prison sentence measure follows a lognormal distribution (Reference Bushway and PiehlBushway & Piehl 2001). I therefore interpret the sentence length results in percentage terms (Reference Fischman and SchanzenbachFischman & Schanzenbach 2012). Coding and descriptive statistics for all variables in the analysis are shown in the Online Appendix Table 1.

Focal Independent Measures

This study's multilevel framework (discussed below) and emphasis on citizenship over time and across districts necessitates measures at different units of analysis (e.g., individual, year, and district). At level 1, the two focal individual measures are the defendants' citizenship status and their race/ethnicity. Citizenship is measured with a dichotomous indicator (1 = noncitizen)Footnote 6 and race/ethnicity is measured using dichotomous variables for black and Hispanic, with white serving as the reference category.Footnote 7 This study covers a period of 18 years (1992–2009). To evaluate punishment trends over this period, I include a measure for time at level 2 ranging from 1 to 18.Footnote 8 Finally, the focal district-level (level 3) measure is the relative change in the proportion of noncitizens adjudicated in the district. This measure captures the minority threat argument which suggests the relative population change of noncitizens will condition the punishment severity for noncitizen offenders.

Individual Independent Variables

I include a broad range of case, legal, and offender level 1 controls to: (1) isolate the effects of citizenship status and to (2) account for differences in case compositions that could explain variation over time and across districts. As previous research using multilevel modeling demonstrates, these controls are fundamentally important when assessing contextual variations in sentencing (Reference JohnsonJohnson 2006). Consistent with prior research, I control for the presumptive sentence set forth by the guidelines (Reference Johnson and BetsingerJohnson & Betsinger 2009). This measure captures the complex interplay among the offense severity level, the criminal history scale, and any sentencing adjustments that affect the final guideline recommendation such as mandatory minimum penalties or obstruction of justice enhancements. Consistent with the length of incarceration measure, the presumptive sentence is capped at 470 months and logged to reduce skewness.Footnote 9 In line with previous federal court research (Reference Doerner and DemuthDoerner & Demuth 2009; Johnson, Ulmer, & Reference Johnson, Ulmer and KramerKramer 2008), I include an additional control for the offender's criminal history score.Footnote 10

I further control for whether the individual was convicted at trial (yes = 1) and whether he was convicted of multiple counts (yes = 1). Additional controls are included for whether the offender was sentenced for a drug, violent, fraud, firearms, or other offense to capture varying sentencing practices by offense type (property offenses as reference category).Footnote 11 Finally, I account for a number of offender characteristics, including the offender's sex, age, and the education level.

Contextual Independent Variables

Multiple time-stable and time-varying district-level contextual measures are included to capture important criminal, legal, practical, and demographic differences between district court communities. Following Reference UlmerUlmer (1997), I divide the 90 districts into small, medium, and large courts based on the number of adjudications within each district. I also include a caseload measure that is captured by the average change in the number of adjudications per judge between 1992 and 2009.Footnote 12 District-level guideline adherence is measured as the average percent of cases sentenced outside the recommended guideline range. As an indicator of the seriousness of the crimes brought before the court, I include the average offense severity score for each district. I also account for changes in the types of crimes handled over the study period by measuring the proportional change in the number of drug and immigration crimes sentenced in each district between 1992 and 2009.Footnote 13 Finally, district demographic differences are captured by the average percent of cases where the defendant is a minority. Combined with the other measures, these interrelated levels of data provide one of the most comprehensive resources for examining criminal sentencing over time and across court contexts.

Analytical Strategy and Logic of Analysis

There are three levels of analysis. The individual level is each sentenced case within U.S. federal courts. The second level is the sentencing year, and the third level is the district court. The data structure of this multilevel framework thus captures the reality that defendants are nested within both time (sentencing year) and location (district court). Though the logic of multilevel modeling in the study of criminal punishment has been discussed elsewhere (Reference JohnsonJohnson 2006; Reference KauttKautt 2002), no research to date has included time as a sentencing context within a multilevel framework. Thus, a brief review of the merits of multilevel modeling provides a useful backdrop for the analytical approach used in this study.

Multilevel modeling techniques provide two important methodological advantages for the present research. First, multilevel models properly adjust the degrees of freedom for the higher levels of analysis to the appropriate sample size. Whereas ordinary least squares (OLS) regression inappropriately bases statistical significance for contextual variables on the number of individual cases, multilevel models adjust the degrees of freedom to correctly represent the number of level 2 and level 3 units.

Second, cases handled within the same year and court likely share similarities and cannot be treated as independent because significance tests would be biased if variation in sentencing is partially determined by district-specific processes that vary over time (Reference Ulmer and JohnsonUlmer & Johnson 2004). By incorporating a unique random effect for each time and district equation, the hierarchical framework used here directly incorporates time-varying and district-level processes while accounting for the interdependence of individuals nested within year and district.

In all models, I treat the sentencing year as a random coefficient which allows for each district to have a unique time trend. This method has several advantages. Methodologically, it avoids artificially inflating the statistical power of the time trend by adjusting degrees of freedom by d-1 districts. More importantly, this is in line with the theoretical focus of examining temporal variation in punishment across districts by providing a critical test as to whether changes over time in sentencing disparities vary across U.S. district courts. According to the theoretical argument developed here, districts are likely to have unique time trends due to varying demographic shifts over this period, thus necessitating that the equations allow for districts to vary over time (but see Online Appendix for an alternative modeling strategy).Footnote 14 The incarceration decision is modeled using hierarchical logistic regression and the sentence length models use hierarchical linear regression. The results reported are based on population-average models and all variables were centered on their grand means.

The first stage of the analysis estimates unconditional models. Substantively, these models estimate the amount of sentencing variation at each level of analysis (individuals, year, and district). These estimates provide useful insights into the relative importance of time period and district contexts in criminal punishment. The second stage investigates the trends in racial/ethnic and citizenship disparities between 1992 and 2009 by including cross-level interactions among race/ethnicity, citizenship, and sentencing year. In this stage, I pay particular attention to the strength of citizenship relative to the Hispanic ethnicity effect as well as the strength of the time trends for the cross-level interactions. The third stage tests the minority threat argument in two important ways. First, I include a cross-level interaction between citizenship status and the relative change in the noncitizen population at the district level. This coefficient estimates whether demographic changes in the noncitizen population condition the punishment of non-U.S. citizens. Second, I include a three-way cross-level interaction among citizenship, sentencing year, and the noncitizen population change. This coefficient estimates whether the trends in the citizenship effect over the last two decades are conditioned by shifts in the noncitizen population. The final stage in the analysis attempts to explain the punishment gap between U.S. citizens and noncitizens. Here I pay particular attention to the role of presentencing detention in explaining the differential punishment of non-U.S. citizens.

Combined, the stages of this analysis answer important questions regarding the significance of time period for understanding criminal punishment, the trends in offender disparities over the past two decades, and whether these trends vary across court communities.

Findings

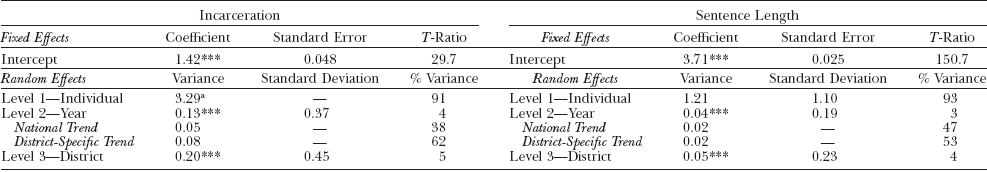

Table 1 presents the results from the three-level unconditional models of incarceration and sentence length. Results suggest that four percent of the total variance in the likelihood of incarceration can be attributed to changes in punishment over time.Footnote 15 In line with theoretical expectations, these changes were not uniform across district courts, as only 38 percent of the variance is due to national changes. The remaining 62 percent represents time-varying district-specific processes. At level 3, roughly five percent is accounted for by differences between federal districts. The estimates for the sentence length analysis are similar, with four percent of the variance at the district level (level 3) and three percent of the variance attributable to time-varying processes. Of this temporal variance, only 47 percent represents national level changes. The estimates for the district-level variance are consistent with prior research (Ulmer, Light, & Reference Ulmer, Light and KramerKramer 2011), and a comparison of the amount of variance at levels 2 and 3 underscores the importance of the current study's emphasis on changes over time. The findings in Table 1 suggest that the sentence year accounts for nearly as much of the overall variance in punishment decisions over the past two decades as the district court. While the district context has received substantial scholarly attention in recent years, the time period in which offenders are sentenced has received considerably less. These results suggest that the temporal context may be an important, yet understudied aspect of criminal punishment. More germane is the next set of results that examine how sentencing practices have changed in the past two decades, and whether different groups experienced these changes equally.

Table 1. Three-Level Hierarchical Unconditional Models of Incarceration and Sentence Length, U.S. Federal Courts 1992–2009

a Intraclass correlations for incarceration are based on the following assumption: level 1 random effect has a variance = π2/3.

*** p < 0.001.

Notes: District-specific variance components at level 2 calculated by including 17 dichotomous measures for each sentencing year (t-1). The remaining level 2 variance equals the district-specific trend. The national trend is calculated as the overall variance minus the district-specific trend.

Time Trends

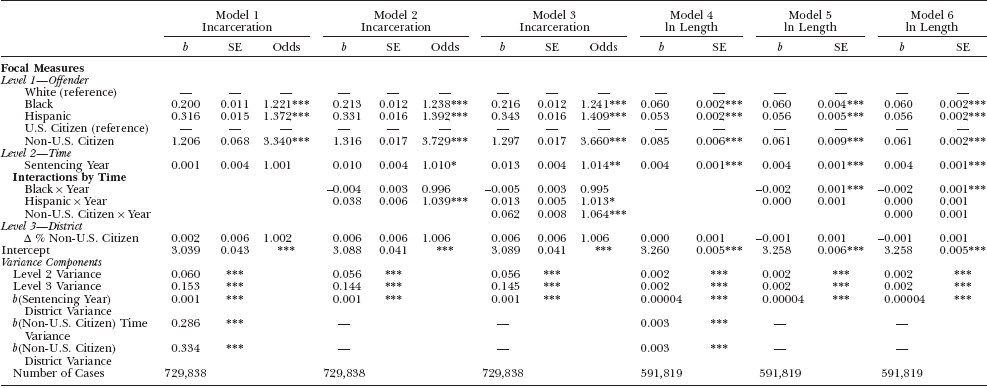

Models 1–3 of Table 2 report the logistic regression results for the incarceration decision, and models 4–6 report the linear regression results for the length of imprisonment. For both decisions, I report first the overall trends in punishment over time (models 1 and 4), then the trends in racial and ethnic disparities (models 2 and 5), and finally, the trends for noncitizens (models 3 and 6). For parsimony, I focus only on the main and interactive effects for the focal independent measures, but note that all models include all level 1, 2, and 3 measures (full models available on request).

Table 2. Select Effects from Three-Level Hierarchical Logistic Regression Models of Incarceration and Linear Models of Sentence Length, U.S. Federal Courts 1992–2009

* p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Notes: Models include all variables shown in Table 1. All estimates are based on population-average models.

Beginning with the incarceration decision, the results in model 1 indicate that black (23 percent) and particularly Hispanic offenders (39 percent) were more likely to be imprisoned compared to whites between 1992 and 2009, net of legally relevant controls. While these effects are consistent with previous research, the effect of Hispanic ethnicity pales in comparison to the consequences of lacking U.S. citizenship, and it is important to note that sensitivity analyses confirm that this is not simply an issue of collinearity between citizenship and ethnicity.Footnote 16 Non-U.S. citizens are over three times more likely to be incarcerated compared to similarly situated U.S. citizens. In this model, I treat citizenship as a random coefficient at levels 2 and 3 to test whether the punishment consequences of citizenship changed over time or vary across district courts. The variance components for model 1 indicate that the likelihood a noncitizen will receive prison time is significantly different over time and across districts, even after controlling for offender, case, and district-level differences. I turn now to examining these specific time-varying processes.

Though blacks and Hispanics are disadvantaged at sentencing, these groups have experienced different trends over the past two decades. According to model 2, whereas racial disparity has been relatively stable over this period, there appears to be a very clear trend indicating increased Hispanic disparity, as indicated by the significant interaction effect between “Hispanic” and “Sentencing Year.” Taken at face value, these results align with the current emphasis in extant research on the increasing importance of Hispanic ethnicity.

However, the results from model 3 show that what appears to be increasing severity against Hispanics is largely attributable to increases in citizenship disparity. Including a cross-level interaction for citizenship and sentencing year reduced the Hispanic ethnicity time trend (Hispanic × Year) by two-thirds. Though the model still evidences ethnic disparity, the results show that not only is the relative citizenship gap more consequential than the gap between racial/ethnic minorities and whites, but the trend analysis suggests this gap has increased more for this group than any other in the past 20 years. According to model 3, between 1992 and 2009, the punishment gap between citizens and noncitizens increased approximately six percent each year.

Turning to the sentence length analysis, model 4 shows that black and Hispanic offenders received slightly longer prison terms compared to whites. However, in line with the incarceration results, the gap between citizens and noncitizens is larger than for other groups. Whereas black and Hispanic offenders received sentences that were roughly five to six percent longer, respectively, noncitizens' prison terms were 8.5 percent longer. Substantively, this corresponds to an additional 6.5 months of incarceration compared to similarly situated U.S. citizens (73.4 months for average U.S. citizens × e (0.085) = 79.9). Similar to the incarceration findings, the variance components suggest the citizenship effect varies both over time and across districts. The direct effect of sentencing year in model 4 indicates that the average sentence length increased over the study period. Models 5 and 6 examine whether these changes were uniform for racial/ethnic minorities and non-U.S. citizens.

The trends in sentence length disparities are largely distinct from those at the incarceration stage. Looking at the full set of results in model 6, the only significant cross-level interaction indicates that disparity against black offenders has decreased modestly over time. For Hispanic and noncitizen offenders, there is little evidence that disparities have changed appreciably.Footnote 17

Taken together, two important findings stand out from Table 2. First, though racial and ethnic disparities have dominated the research on legal inequality, noncitizens are more disadvantaged than racial/ethnic minorities at sentencing. This pattern holds across both sentencing decisions, though the effects are particularly pronounced at the incarceration stage. Second, the bulk of the increase in the Hispanic ethnicity effect over time is attributable to increasing disparity against non-U.S. citizens.Footnote 18 These findings highlight the importance of citizenship for understanding the dramatic increase of Hispanics in federal courts, and cautions against focusing on ethnicity without an equally concerted emphasis on citizenship.

The next set of analyses examines whether demographic changes in the noncitizen population condition the citizenship penalty as well as the trends in the punishment of noncitizens over time.

District Context

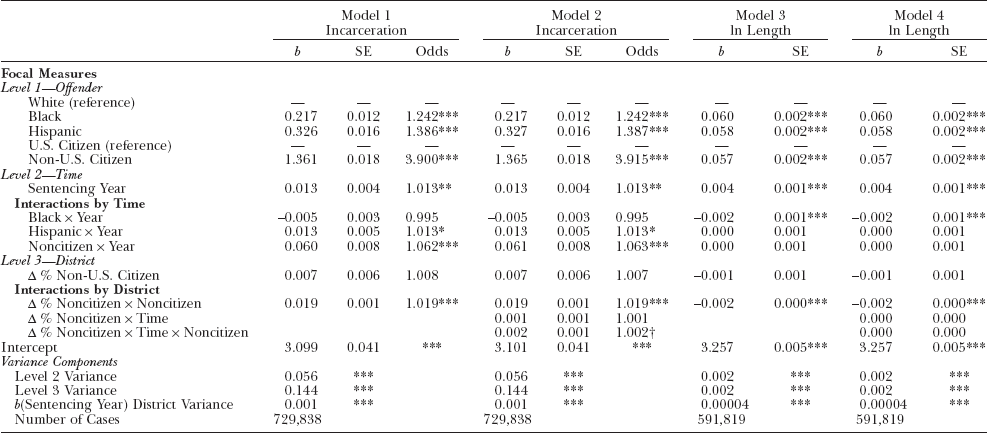

Table 3 presents the results for interactions among citizenship, sentencing year, and changes in the noncitizen population at the district level, controlling for individual case and offender characteristics and multiple district-level processes. Model 1 is almost identical to model 3 in Table 2 with one exception—the inclusion of a cross-level interaction between the district percent change in the noncitizen population (level 3) and citizenship (level 1). Consistent with the central tenets of the minority threat argument, the positive and significant interaction indicates the likelihood that a noncitizen will be incarcerated is higher in districts where the noncitizen population increased in recent decades.

Table 3. Select Effects from Three-Level Hierarchical Models of Incarceration and Sentence Length—District-Level Context

† p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Notes: Models include all variables shown in Table 1. Estimates are based on population-average models.

Model 2 pushes this logic further by adding a three-way cross-level interaction to investigate whether the trend in the citizenship penalty is conditioned by changes in the noncitizen population. The results are also in line with minority threat arguments. The three-way interaction is positive but only marginally significant (b = 0.002; p < 0.072). Taken together with model 1, the results suggest the punishment of noncitizens is conditioned by district demographic shifts in two important ways: noncitizens are more likely to receive a prison term in districts where noncitizens are increasing, and while this sentencing penalty has increased over time in general, the increase has been greatest in districts with growing noncitizen populations.

Models 3 and 4 replicate these analyses on the length of incarceration. The results in model 3 suggest that noncitizens receive longer prison sentences overall, but unlike the imprisonment findings this punishment gap decreases slightly as the noncitizen population increases. This could reflect the fact that noncitizens face deportation after incarceration and as judges increasingly sentence non-U.S. citizens they may see little value in imprisoning alien offenders for lengthy periods when federal prisons are operating at well over 100 percent capacity (Federal Bureau of Prisons 2010). Based on the results in model 4, these same population shifts appear to have a null effect on the citizenship trends over time at the length stage. This is perhaps unsurprising given the results from Table 2 which show the citizenship gap for sentence length decisions has not changed appreciably over time.

Explaining the Citizenship Effect

Unlike U.S. citizens, noncitizen offenders face the likelihood of deportation upon adjudication, especially in recent years as criminal deportations have reached historic highs. Though outside the purview of district courts, this unique criminal justice outcome may factor into criminal court decisionmaking by increasing the likelihood that criminal aliens will be detained during the adjudication process and by limiting judges to consider only incarceration options. This suggests that presentencing detention may play an important role in the punishment of non-U.S. citizens. I investigate this possibility in Table 4 using data from 2008 to 2009.Footnote 19

Table 4. Select Effects from Three-Level Hierarchical Regression Models—Citizenship and Presentencing Detention, U.S. Federal Courts 2008–2009

*** p < 0.001.

Note: Estimates are based on population-average models.

Model 1 shows that noncitizens are over five times more likely to receive incarceration net of legally relevant controls in 2008–2009. Consistent with expectations, including a measure for detention prior to sentencing in model 2 explains a considerable portion of this punishment gap, decreasing the citizenship coefficient by nearly 30 percent. This pattern is even more pronounced in the sentence length analysis shown in models 3 and 4. Comparing the citizenship results in these models suggests that a major explanatory factor in this association is the fact that noncitizens are far more likely to be imprisoned prior to final sentencing (90 percent of noncitizens are detained compared to 63 percent of U.S. citizens). However, it is important to note that the punishment consequences of lacking U.S. citizenship are not solely a function of detention and that noncitizens are not simply being detained pending deportation and being sentenced to time already served. Models 5 and 6 report the citizenship results where all offenders who received credit for time served are removed. The results are nearly identical to those reported in models 1 and 2. This suggests that while detention helps explain the observed citizenship results, presentencing detention reflects an earlier phase in criminal processing that is a part of a broader pattern of punitiveness against non-U.S. citizens, culminating in more incarceration and longer prison terms.

Discussion

Racial inequality under the law has been a central focus among legal scholars for nearly a century, yet recent research suggests Hispanics may have replaced African Americans as the most disadvantaged group at criminal sentencing. The findings from this study indicate the axes of legal inequality have indeed shifted in recent decades, but my inquiry into the long-term punishment trends for noncitizen and minority offenders suggests that non-U.S. citizens may be the new face of legal inequality in the United States.

Not only are noncitizens treated more harshly at sentencing, but the relative gap between citizens and noncitizens at punishment is greater than the gap between white and minority offenders. This relationship holds for the incarceration and sentence length decisions. In addition, the results suggest that over the past two decades the punishment gap between citizens and noncitizens has widened at the incarceration stage. Taking these trends into account significantly alters the Hispanic effect over this period—reducing it by two-thirds. In short, what appears to be increasing Hispanic disparity over the past 20 years has been driven primarily by increased punitiveness against non-U.S. citizens.

Given the traditional focus on race in stratification research generally and legal studies specifically, it is perhaps not surprising that contemporary research on legal inequality has stayed largely within the confines of racial/ethnic relations by emphasizing Hispanic ethnicity. However, as the United States continues to receive international migrants and noncitizens become an increasingly prominent group in society, perhaps the time has come to look beyond these traditional markers of stratification. Estimated at over 22 million, the population of noncitizens in the United States is larger today than at any point in American history (Reference Gibson and LennonGibson & Lennon 1999).

By clarifying the theoretical linkages between citizenship as a mechanism of stratification and an outcome of cultural compromise with sociolegal work on inequality and cultural distance within the focal concerns framework on punishment, the goal of this study is to widen the theoretical and empirical scope of legal inequality research. Just as one's location in the social structure has implications for the treatment of U.S. citizens in legal institutions, noncitizens occupy a uniquely disadvantaged niche in U.S. society, as their formal exclusion exacerbates other social inequalities. The theoretical discussion and findings from the current study place citizenship firmly within the scholarship on punishment and inequality, thus expanding the discourse on contemporary legal stratification and placing citizenship alongside other markers of inequality.

The findings are in line with focal concerns perspective and Reference BlackBlack's (1976) suggestion that cultural dissimilarity between legal authorities and defendants leads to enhanced punishment. As literal “outsiders” of the state, I find that noncitizens pay a significant “penalty” at sentencing. This may be due, in part, to the practical constraints that eventual deportation places on criminal justice decisionmaking, which funnel noncitizens toward prison sentences. This interpretation is consistent with recent research on the convergence between criminal and immigration law. A centerpiece of this nexus is the increasing reliance on incarceration for migration control. During the same period that the state sought to dramatically increase the social control of immigrants, the findings presented here suggest that the likelihood of receiving incarceration for non-U.S. citizens increased. It is important to note that this relationship is observed among nonimmigration offenders. Thus, while this article adds to an emerging literature that finds noncitizens increasingly entangled in coercive state controls, it also suggests that the punitive turn in migration control stretches well beyond the border.

Consistent with minority threat arguments, I find that district-level demographic shifts conditioned the punishment of non-U.S. citizens over the past two decades, net of a host of individual, case, and district-level covariates. The analysis revealed noncitizens are more likely to be imprisoned in districts where the noncitizen population is increasing, and citizenship disparity at the incarceration stage became more pronounced over time in these same districts. However, these same demographic shifts had a countervailing effect on the length of imprisonment—actually decreasing the citizenship “penalty” in districts with increasing noncitizen populations. One plausible explanation for this divergence points to an additional punishment noncitizens face—deportation. Given the lengthy prison terms federal offenders face generally and the likelihood of deportation after noncitizens complete their sentences, it is possible that as judges increasingly punish non-U.S. citizens they see little value in excessively long prison terms. Future research would do well to explore this possibility through qualitative research with federal judges.

Though I emphasize the theoretical and empirical implications of the citizenship findings, an additional contribution of this work concerns temporal variation in punishment decisions. Over the past decade, analyses of court contexts have been a major thrust in punishment research and for good reason—the court context explains a small yet substantively meaningful amount of variation in sentencing outcomes. There has not been an equally concerted focus on the temporal context of punishment decisions despite strong theoretical reasons to expect variations over time. The results presented here add empirical validity to these theoretical motivations. The unconditional models suggest that temporal changes account for roughly as much variation in sentencing outcomes as the district court context, and the interaction models clearly illustrate temporal variation in several extralegal effects. Although additional research is needed to further explore the connections among individual factors, temporal changes, and court contexts, this analysis provides a useful first step toward examining this nexus. In doing so, it raises a series of consequential questions central to punishment research, such as which sentencing factors vary over time, why do they change, and what legal, political, or demographic macro-level processes condition these trends?

Though the current study provides an important foundation for future research to expand the scope of legal inequality scholarship and to investigate temporal trends in social control institutions, this analysis is not without limitations. First, with the existing data, I could not definitively determine the mechanisms driving the effects shown, a limitation of nearly all quantitative criminal justice research. Second, one must always be cautious to draw conclusions that disparity implies discrimination. It is possible that additional information about case characteristics or processing could reduce the effects shown. Having said that, the federal data are remarkably inclusive with regard to controls, and the results presented are in line with theoretical predictions, thus diminishing the likelihood that the results are solely due to unobserved heterogeneity. A third limitation is the inability to fully account for decisions made prior to sentencing in the criminal justice process, including arrest and prosecutorial charging practices. While studies have investigated disparities at these earlier stages (Reference Bushway and PiehlBushway & Piehl 2007; Reference DemuthDemuth 2003), like the extant punishment literature, this research largely focuses on racial/ethnic minorities (but see Reference Shermer and JohnsonShermer and Johnson [2010] for an exception). As a result, citizenship remains understudied at these stages as well. Given the jurisdictional differences in immigration policing, detention programs, and case processing (Reference Seghetti, Ester and GarciaSeghetti, Ester, & Garcia 2009), this appears to be a particularly fruitful area for future inquiry. The results presented in this study suggest that imprisonment prior to final sentencing plays an important role in explaining the punishment gap between citizens and non-U.S. citizens, but these decisions still occur after police and prosecutorial decisionmaking. Future research should not only investigate noncitizens in these earlier phases, but should also identify the cumulative influence of citizenship status through criminal case processing.

Another area for future consideration is the effect of citizenship in state courts. Though the extant research largely points to the punitive turn in migration control at the federal level, state and local authorities are playing an increasing role in border security today as Congress has gradually broadened the authority for state and local law enforcement officials to enforce immigration law (Reference Seghetti, Ester and GarciaSeghetti, Ester, & Garcia 2009). In addition, some of the nation's most contentious immigration battles have occurred at the state level—California's Proposition 187 and Arizona's SB 1070 being two prominent examples. Noncitizens also represent sizeable populations in several state prison systems, including over 18,000 in California, nearly 10,000 in Texas, and roughly 6,000 in New York and Florida (Reference Guerino, Harrison and SabolGuerino, Harrison, & Sabol 2011). Research on state court outcomes would further refine the understanding between punishment and citizenship. But first, future work in this area would benefit from new data collection as citizenship information is often not collected in state court statistics.

Mindful of these limitations, the key findings from this study have important implications for understanding the future of legal inequality and the disadvantages of lacking state membership in a world increasingly characterized by international migration. Though the United States is often an outlier in the context of punishment, dramatic increases of incarcerated foreigners place the United States within a conspicuously broader punitive trend (Reference Bosworth and KaufmanBosworth & Kaufman 2011). Across Europe, noncitizen prisoners have increased rapidly in recent decades—in both absolute and relative terms (Reference van Kalmthout, Hofstee-van der Meulen and Dunkelvan Kalmthout, Hofstee-van der Meulen, & Dunkel 2007; Reference WacquantWacquant 1999). Reference Welch and SchusterWelch and Schuster (2005: 345–47) argue that these trends exemplify a “globalizing culture of control,” one ever more reliant on the detention, incarceration, and expulsion of noncitizens as coercive forms of state social control. In light of these trends, future research would do well to investigate the consequences of lacking state membership beyond U.S. courtrooms. If the findings from the current study are partially a reflection of this new culture of control, they suggest that as international migration increases, the central axes of legal inequality may no longer be defined by internal divisions within society, but by the division between state and nonstate members.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Online Appendix Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Offenders Sentenced in U.S. Federal Courts, 1992–2009.

Online Appendix Table 2. Select Effects from Revised Three-Level Hierarchical Models—Districts (Level 2) Nested within Sentencing Year (Level 3).