Borderline personality disorder is a common and often severe mental health problem with a median prevalence from nine epidemiological studies of 1.6% (Reference De Girolomo, Dotto, Gelder, Lopez-Ibor and AndreasonDe Girolomo & Dotto, 2000). The main clinical challenge in centres that treat the disorder is managing chronic suicidality (Reference ParisParis, 2005). At least three-quarters of people with the disorder attempt suicide and approximately 3.0-9.5% eventually complete suicide (Reference McGlashanMcGlashan, 1986; Reference StoneStone, 1993). Emerging evidence about positive treatment outcomes challenges widely held doubts about whether borderline personality disorder is treatable. The Department of Health (2003) paper Personality Disorder: No Longer a Diagnosis of Exclusion outlines effective treatments for personality disorders and lists dialectical behaviour therapy (Reference LinehanLinehan, 1993) as one of the few evidence-based treatments. Blennerhassett & O'Raghallaigh (2005) recently considered whether dialectical behaviour therapy could be translated to community mental health settings given the limited resources and shortage of trained staff. They predicted that this therapy would be confined to specialist settings. We describe the evolution of a small service for dialectical behaviour therapy in Newham, East London, since its inception in 2003. We present the structure of the programme, demographic data, treatment outcomes and costs.

Method

The Newham project is a comprehensive treatment service for people aged 18-65 years with borderline personality disorder and/or frequent self-harming behaviour and/or chronic suicidality. The project offers standard out-patient dialectical behaviour therapy according to Linehan (Reference Linehan1993). The project provides care coordination according to the care programme approach (CPA; Department of Health, 1999), including consultant responsibility and medication management. To achieve adherence to the original dialectical behaviour therapy model the team participated in accredited dialectical behaviour therapy training in the USA. The team meets weekly for peer supervision, arranges regular consultation with expert dialectical behaviour therapy trainers and, subject to consent, individual sessions are video-taped and reviewed.

The data for this study were obtained from routine documentation and specific programme records, such as the service user's weekly diary card which tracks among other things self-harming behaviour. The individual therapist transfers the information on the diary card to an outcome data sheet which is then entered into a database containing information on behavioural changes in terms of self-harm and hospitalisation. Referrals to the service are accepted from all parts of local mental health services (mainly community mental health teams, wards, psychiatrists and psychotherapists), but not directly from primary care. Two clinicians assess each person referred in two 1-hour sessions. Assessment includes a detailed history of self-harm, service use, history of trauma, Axis 1 comorbidity and substance misuse.

All people referred are interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II; Reference First, Gibbon and SpitzerFirst et al, 1997). The service does not exclude people with psychotic disorders, substance misuse disorders, other Axis 1 disorders or mild intellectual disabilities. People with antisocial personality disorder are not accepted. They can, however, be referred to the Department of Health Forensic Pilot Project for Severe Personality Disorder in Hackney, East London (http://www.elcmht.nhs.uk/ourservices/detail_services.asp?id270).

Individuals are offered a treatment contract for 1 year in the first instance. Treatment consists of one individual session (1 hour) and one group session (2 hours of skills training) per week. Telephone coaching from the individual therapist is available between sessions, 7 days per week, with some variation depending on clinicians' personal preferences but typically from 08.00h to 20.00h.

In the first year of treatment we aim initially to stop life-threatening and self-harming behaviours (target 1), to stop treatment-interfering behaviours such as non-attendance at sessions, chronic lateness or disruptive behaviour (target 2), and to stop crisis-generating behaviours such as substance misuse (target 3). Weekly group sessions teach new skills in mindfulness, emotional regulation, interpersonal effectiveness and distress tolerance. This first stage of treatment can be followed by trauma-based work to reduce post-traumatic stress (Reference Foa and Olasov RothbaumFoa & Olasov Rothbaum, 1997). This can be provided by the dialectical behaviour therapy service or other services (i.e. London Institute of Psychotrauma; http://www.elcmht.nhs.uk/ourservices/detail_services.asp?id242).

The individual dialectical behaviour therapy therapist also assumes the role of the care coordinator. Care coordination for people in this programme - on standard or enhanced level of CPA - includes medication review, ongoing risk assessment, CPA meetings, liaison with primary care and referrals to statutory and non-statutory services. The consultant psychiatrist in the dialectical behaviour therapy team offers regular medication reviews. Service users who disengage (attendance of less than 75% of individual/group sessions over any 8-week period) are referred back to generic community mental health teams (CMHTs), or to primary care depending on their needs at discharge.

The project evaluation involved systematic data collection on self-harm and suicide attempts (12 months pre-treatment and during treatment), psychiatric in-patient stays (12 months pre-treatment and during treatment), quality of life using the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA; Reference Priebe, Huxley and KnightPriebe et al, 1999) at baseline and 12 months, and severity of borderline symptoms (Zanarini Rating Scale; Reference Zanarini, Vujanovic and ParachiniZanarini et al, 2003) at baseline and 12 months. Information on self-harm in the year prior to treatment is obtained via self-report at the start of and during treatment from diary cards which users complete on a weekly basis. Users who forget to complete their diary cards throughout the week are asked to complete a diary card in session.

Results

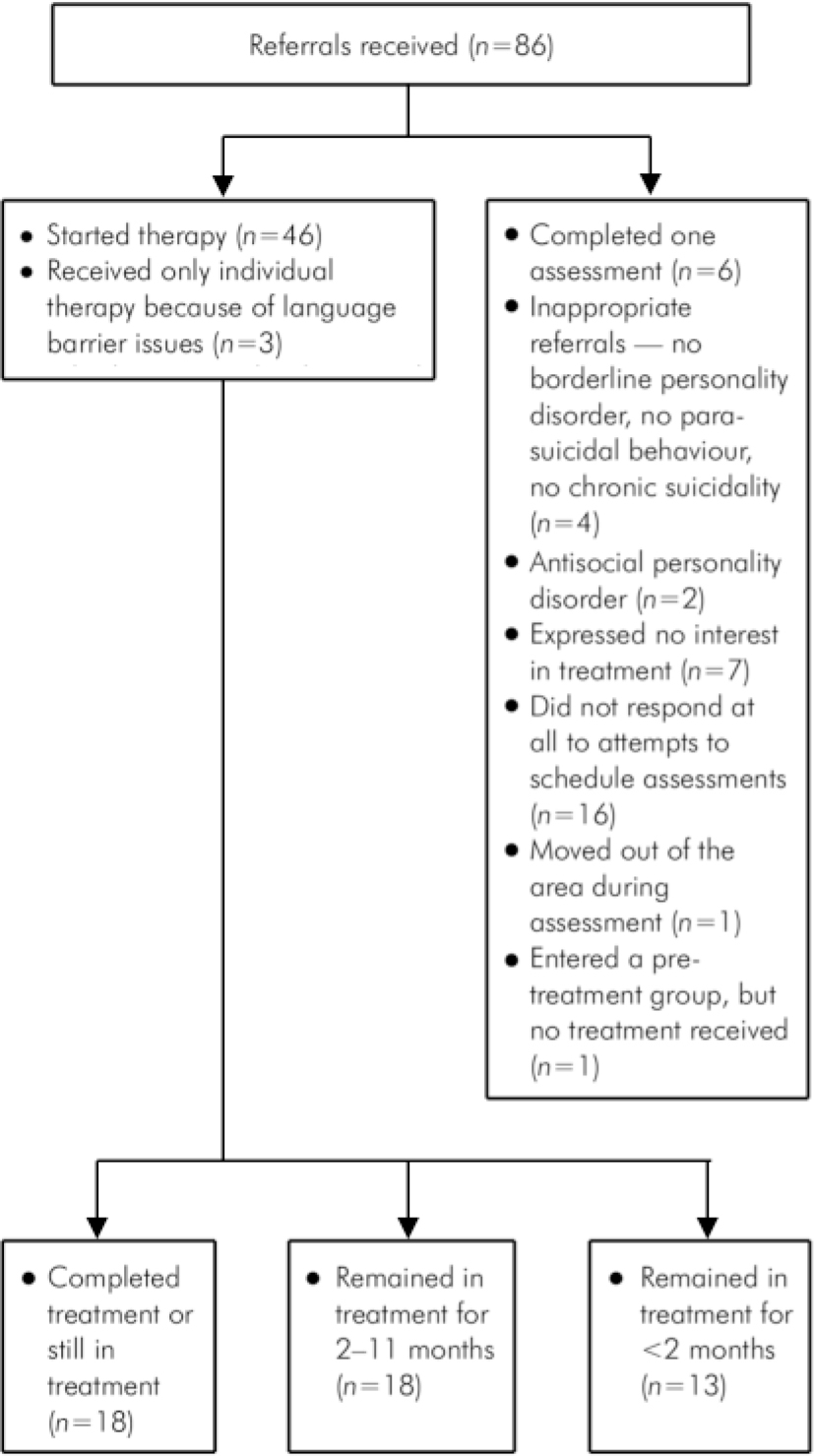

Between March 2004 and October 2005, 86 people were referred from secondary mental health services including CMHTs, acute in-patient wards, acute day hospital and other psychotherapy services (Fig. 1). Forty-nine (57%) were taken on for therapy. Nineteen percent of referrals (n=16) did not respond to attempts to schedule an assessment.

Fig. 1. Referral pathways

Of the 86 people referred, 7% (n=6) attended only one of the two assessments. In two instances there was no further contact with the service, so the reasons why the service user did not attend are unknown, and the remainder stated that they were no longer interested in the therapy. Two of the 86 service users referred (2%) were excluded with a diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder. Four (5%) were excluded because they were not suicidal, not engaging in parasuicidal behaviour and did not meet the criteria for borderline personality disorder. One person moved out of the area during the assessment. One person entered a pre-treatment group and did not go on to receive treatment, and 3 people were in individual therapy only because group therapy was considered too difficult because of language issues.

Out of 49 patients who started dialectical behaviour therapy, 31 (63%) dropped out before completing 12 months of treatment; 13 (42%) dropped out of treatment in the first 2 months, some never attended more than one appointment. The mean length of time in treatment was 5.5 months. Outcome data were obtained from 32 service users who stayed in treatment for more than 3 months. Compared with 12 months pre-treatment, self-harm and in-patient (hospital) use reduced dramatically once people entered the programme, with incidents of self-harm per service user per month reducing from 5.3 for pre-treatment (over 12 months) to 1.2 in treatment, and number of hospital days per service user per month decreasing from 1.66 pre-treatment to 0.11 once in treatment. Demographic data, clinical data and results of the SCID-II assessments are outlined in Table 1 and show that most service users fulfil criteria for personality disorder in at least two clusters.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 49 service users

| Age, years: mean | 33.21 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 6 (12) |

| Female | 43 (88) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Black | 8 (16) |

| White | 35 (71) |

| Asian | 4 (8) |

| Others | 2 (4) |

| Comorbid substance misuse, n (%) | 13 (26) |

| Comorbid Axis 1 disorder1, n (%) | 33 (67) |

| Axis 2 (SCID-II results), n (%) | |

| Avoidant | 21 (42) |

| Dependent | 14 (28) |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | 15 (30) |

| Paranoid | 25 (51) |

| Schizotypal | 10 (20) |

| Schizoid | 2 (4) |

| Histrionic | 3 (6) |

| Narcissistic | 3 (6) |

| Borderline | 45 (91) |

| Patients on standard CPA, n (%) | 35 (71) |

| Patients on enhanced CPA, n (%) | 14 (29) |

The programme runs on an annual budget of £92 000, including staff costs, training costs, costs for expert supervision and basic equipment (for example digital video cameras). Costs for the premises were not included. The cost of the programme adds up to £400 per patient per month in treatment. All team members work in other adult mental health settings in Newham (CMHTs, in-patient wards and primary care counselling) and dedicate only part of their working time to dialectical behaviour therapy, with the exception of the part-time programme manager who works exclusively for this service. All team members are individual therapists, care coordinators and skills trainers. Staffing includes one consultant psychiatrist (0.2 whole-time equivalent; WTE), two psychologists (0.7 WTE), two community psychiatric nurses (0.3 WTE) and two social workers (1.0 WTE). In addition, the team provides special interest sessions and training in dialectical behaviour therapy for a specialist registrar (0.2 WTE).

Discussion

The study shows that contrary to the scepticism expressed by Blennerhassett & O'Raghallaigh (2005) dialectical behaviour therapy can be implemented in secondary mental health services at modest costs. Staff satisfaction is perceived as high and staff retention has not proved difficult. The additional burden of taking crisis calls from service users out of office hours was smaller than expected, and has not been a matter of dispute.

The dramatic reductions in hospital use and frequency of self-harm once service users entered the programme were unexpected in the UK context and have helped this new service to survive in an extremely tight financial climate.

The number of drop-outs from the programme is high and needs to be looked at in more detail. It seems to improve as the programme evolves and in our view represents the learning experience of the team with its service users. As mandated by the dialectical behaviour therapy protocol, the team observes strict rules on attendance at therapy sessions including group work. This was a new experience for some service users, and also for staff.

There are several limitations to our study: the relatively small sample size; the enthusiasm of people creating a new service which tends to slow down once routine sets in; the lack of a control group or comparable data on how people with borderline personality disorder or chronic self-harming behaviour perform in routine clinical settings in the UK; and technological limitations regarding the existence of reliable databases with information on the use of particular services, such as accident and emergency, around the trust. Similar to other studies this evaluation, so far, only looks at the first year of the therapy.

People in our project who complete the first year can move on to specific trauma work with the Newham Dialectical Behaviour Therapy Team (4 service users so far) or the Institute for Psychotrauma. Those service users who decide to finish the therapy after 1 year are referred back to their CMHTs or their general practitioners. The decision is taken at a CPA meeting and mainly based on service users' preference. A common theme at these meetings is that after intensive dialectical behaviour therapy there is not much a CMHT can offer and people decide to move on from mental health services. Some service users, however, prefer the safety net of having a care coordinator or seeing a psychiatrist at an out-patient clinic. A randomised controlled trial of an integrated dialectical behaviour therapy service compared with routine CMHT care could provide more clarity about the usefulness of dialectical behaviour therapy in UK mental health services.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.