Introduction

We stood outside the building where the meeting had been taking place, and I decided to ask the French General an off-the-topic question:Footnote 1 What do you think the core roles of the military institution in democratic societies are today? He was caught a bit off guard by the question, then reflected for a second and said:

It is a really tough question, and I am not sure there is a clear answer. But as an institution, we're tasked with carrying arms in society, so our roles should reflect that.

This brief anecdote illustrates a much broader debate about what exactly the military's core roles in contemporary society are, and the answer appears to be all but self-evident, just as the General pointed out.

The military institution is one of the state's core institutions. With the defence of the territorial integrity of the state as its main role, some even consider it the most important of all state institutions.Footnote 2 Yet, since the end of the Cold War, the security environment has gone through a radical transformation, with the decline of old threats and the emergence of multiple new, complex threats.Footnote 3 To remain relevant, the military has adapted to the new context by taking on new, and at times, contradictory roles and tasks. Indeed, it has moved from having a rather narrow focus on external defence of the national territory by the management and implementation of lethal violence, to a wide range of tasks both within and outside of the state, with a significant variation in the use and level of violence. Faced with a swiftly changing security context, the military has thus proved to be a highly versatile organisation. Analysing this versatility is important to better assess its utility, performance, and position in society and thereby also increase our understanding of contemporary civil-military relations.Footnote 4

In this article we therefore ask: (1) what role does the military play in contemporary industrialised, democratic societies, and (2) what type of civil-military relations arise from these roles? To answer these questions, we examine academic literatures related to the military's roles and tasks in society on the one hand, and we analyse official security and defence policy documents on the other, as we believe they outline current expectations for the military as a state institution. We have limited the scope of the analysis to industrialised democratic states, and for our examination of official documents, we have further narrowed this category down to the 37 OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) member states. The most recent authoritative government documents on defence and security, such as White Papers, policy directives, and strategic guidelines from these 37 countries, have been assessed to get a current understanding of the roles that the military is expected to play in these countries.Footnote 5 This being said, we have occasionally also drawn examples from non-OECD states, as the roles and tasks are similar and follow many of the same trends as the OECD states.

The military's transformation during the past three decades has drawn significant attention from academics and policymakers. Militaries’ tasks in international peacekeeping missions has produced its own field of research,Footnote 6 while the increasingly blurred boundaries between the internal and external security forces have led to important analyses, evoking the unintended consequences of such developments.Footnote 7 As security sector reform and capacity building programmes have become important aspects of peacebuilding processes, the military's tasks in security force assistance have increased, paving way for an emergent subfield of its own.Footnote 8 Focus has, however, also remained on the military's traditional role as the defender of the national territory, especially due to the past few years’ revival of great power competition. Yet, while research has documented the military's evolution in these different roles over the past decade, an overarching analysis identifying and analysing the military's contemporary core roles is still lacking. This study attempts to fill that lacuna, by first, identifying and analysing the roles for the military institution in contemporary society and second, to reflect on how these roles influence current civil-military relations. Such an analysis is important to increase our understanding of the diverse challenges and demands that the military institution faces today, but also to evaluate its performance, its needs, and its position in contemporary society. Our exploration, therefore, both draws upon, and contributes to, the fields of military sociology and civil-military relations. Our hope is that this study can serve as a contemporary basis for further studies exploring military roles and their impact on civil-military relations. A basis that provides a contextual and comparative understanding of what is expected by one of the most important state institutions in society.

Yet, what exactly do we mean when we talk about roles, tasks, and missions? In spite of their widespread usage, there is rarely consensus on what they mean. Starting from a basic understanding of roles as socially constructed, we draw on Paul Shemella's work and define role as ‘a broad and enduring purpose’, whereas tasks or missions are actions to be taken, which might change over time within the remits of one role.Footnote 9 Hence, whereas the military's engagement in peacekeeping might be considered a role, contribution with peacekeeping troops to the UN mission in Mali is a task. The two categories are thus distinct, yet their relationship is complex, as some tasks or missions can transform into roles over time, sometimes through novel legislation.Footnote 10 The military's domestic counter terrorism tasks have, for example, been transformed to roles in some states, where they have taken on a broad and enduring character. These definitions are the starting point for our study, yet we unwrap the discussion on their complex interrelations further on in the article.

In a first part, drawing on an extensive literature review, we distinguish global trends that have shaped and diversified roles and tasks within the military, such as the changing geopolitical threat picture, globalisation, and relatedly, the blurred boundaries between internal and external security. In a second part we identify and analyse three core roles for the military, each entailing important subroles and tasks, drawing on both the academic literature and the official documents. In a third section, we build upon the previous findings and draw on the academic literature to reflect on how these roles and tasks affect contemporary civil-military relations. We point to a paradoxical development whereby the military is both more distant from the society it is supposed to protect because of its professionalisation, while due to its broader domestic roles, it is closer and more visible to the civilian population. At the same time, we discern a mutual rapprochement between the military and the political world which evokes classical questions about the military's apolitical stance anew. We conclude by reflecting on the challenges that these trends may have for the military as an institution.

Geopolitical changes and blurred boundaries

The military has often been described as a ‘total’ institution, as an institution with a total character that is symbolised by a barrier to social interrelations with the outside.Footnote 11 It is at its very core an institution whose identity is built upon the differentiation between the insiders – the soldiers and officers – and the outsiders: the civilians.Footnote 12 The voluntary isolation, both the physical – exemplified by separate infrastructures – and the psychological separation – in the sense of constructing distinct, collective identities – from the rest of the society, are characteristics that define the military institution. Yet, in spite of its sequestration from the civilian world, the military organisation remains an open-ended system characterised by its interdependence of, and constant exchanges with, its environment.Footnote 13 Morris Janowitz has, for example, in contrast to Erving Goffman and Samuel P. Huntingon, argued for the importance of the military's connection with society, and Chiara Ruffa, Christoph Harig, and Nicole Jenne point out that we have come a long way from the caricature of a total institution, in this Special Issue's introduction.Footnote 14 As such, the different threats that the environment harbours, and which the military is expected to confront, will determine the military profession, its structure, and the nature of the civil-military relations that follow from the military's functions and roles.Footnote 15

The past three decades, since the end of the Cold War, have seen significant changes to the roles, tasks, and structures of the armed forces, mainly pushed by external drivers, such as (geo)political, economic, social, and technological forces.Footnote 16 The early post-Cold War period between 1990–2001, the ‘postmodern’ era, was characterised by downsizing, professionalisation, and technological evolution.Footnote 17 A significant reduction of military expenditures, personnel, and production of armaments was one of the first impacts of the end of the Cold War on the military. This downsizing was not only due to an increased budget pressure,Footnote 18 but also to the technological evolution and the change in threat picture.Footnote 19 The technological progress, which was clearly demonstrated in the American technological superiority during the first Gulf War in 1991,Footnote 20 came at a time when subnational threats were on the rise and the need for mass armies decreased.Footnote 21 While direct territorial threats to the state itself diminished, regional instability due to civil wars, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, put new demands on the armed forces.Footnote 22 Together, these factors: budget pressure, technology, and a changing security environment, pushed states to abandon large conscription armies in favour of smaller and more flexible all-volunteer forces.

To tackle these newer types of threats, the military had to restructure and provide small, rapid, and flexible expeditionary missions for both warfighting and peace operations.Footnote 23 Globalisation and the increased focus on human rights in the 1990s together with technological evolution, which made it possible to see war, terrorist attacks, or other types of atrocities on television,Footnote 24 pushed for new expectations on the military to engage in peacekeeping activities.Footnote 25 The military's new, smaller, and flexible units, and the increasing need for expeditionary mission capabilities also drove a development of collaboration across national boundaries,Footnote 26 exemplified by UN peacekeeping missions, but also by various coalitions and joint operations.

The geopolitical context took a new turn following 9/11 in 2001 with the US-launched ‘war on terror’, and a renewed focus on transnational threats such as terrorism, climate change, and trafficking. The ‘borderless’ threats underlined the interconnectedness between states and individuals, but also blurred the boundaries between internal and external security, bringing the military closer to internal security issues.Footnote 27 As a result, during the past two decades, the military has progressively become used to provide domestic security by patrolling airports and train stations to counter terrorism; combatting illegal immigration through border security functions; and by providing assistance during natural disasters and pandemics.Footnote 28 Internal security forces, such as the police, have also experienced an evolving militarisation evidenced in a rapid proliferation of police paramilitary units, modelled on military special operations groups with heavier weapons, full ballistic gear, and aggressive patrol work.Footnote 29 This convergence of tasks between military and police forces has been reinforced and reproduced globally as military assistance programmes have replicated domestic force structures in other states.Footnote 30

Arguably, a new ‘multipolar’ period, which combines threats of earlier eras ranging from terrorism, civil wars, and climate change to interstate wars and nuclear threats began around 2014.Footnote 31 China's economic and military rise, in combination with Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014, and invasion of Ukraine in 2016, started a new period of interstate tensions,Footnote 32 which increased with the election of US President Trump in 2016, leading to fraught alliances and broken agreements. These developments have brought global power competition back to the fore, which is reflected in most of the more recent documents we examined. They also make the current period one of the most complex and instable security environments in recent times, putting unprecedented demands on the military to adapt to highly different types of threats and challenges,Footnote 33 subsumed under three core roles.

Core military roles in contemporary society

This section explains why it is important to identify the roles and tasks of the military. As one of the central state institutions, with the capacity and mandate to use lethal violence, the military is a powerful organisation. In spite of post-Cold War declining defence budgets in some regions, and the restructuration of the armed forces during the 1990s leading to smaller organisations, it still represents one of the largest employers in most societies, with a significant number of associated industries, such as research and development, and military industries, generating further employment. Understanding what such a key state institution does, and what it should do, is crucial to hold it accountable, to evaluate its performance and to assess its needs. It is also essential in order to analyse the evolution of civil-military relations in society, which, inherently, is imprinted by the nature of the roles and tasks that are assigned to the military.

The military as a state institution is shaped both by a functional imperative stemming from the threats to society's security, and a social imperative arising from the social forces, ideologies, and institutions dominant within the society.Footnote 34 The role and the tasks of the military are hence socially constructed, shaped by both key actors’ understanding and role conceptions and of the system and the challenges with which they interact. Against the backdrop of the previous section that examined trends that have influenced the expectations and functions of the armed forces during the past decades, in this section, we draw on seventy official security documentsFootnote 35 together with our reading of the academic literature, to identify three core roles, each entailing specific subroles, for armed forces of today. We have collected the most recent official security documents that detail the military's roles for each of the 37 states, in some cases there have been several such documents, whereas in others not. We have read each document examining how the military's roles and tasks have been described and identified. We have used an inductive method, by coding the documents manually according to the roles found. Added to this material, one of the authors has had several informal discussions with military officers, soldiers, and academic experts on the military, during the course of this research project, about their perceptions of the core roles and tasks.

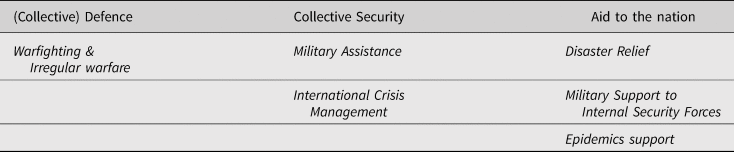

Through our readings and discussions with academic colleagues and militaries, we have come to the conclusion that there is not one way of categorising the roles and tasks, but multiple. One way is through context: what are the roles of the military in peace time, in low-intensity conflict or high-intensity conflict. Another way is to categorise them depending on what they are doing on a more abstract level: providing help, cooperating, competing, participating in conflict, or warfighting.Footnote 36 A third way is to define them from a geopolitical perspective: national, regional, or international roles,Footnote 37 while a fourth is to divide them into areas of function: internal security, deterrence, and compellence, and operational engagement.Footnote 38 These examples illustrate that there are many different ways to identify and categorise the armed forces’ core roles. The academic literature review, together with the examination of the official documents and the interviews have all been combined in our analysis below, yet we have chosen to draw heavily on the roles outlined in the majority of the official documents, which we see as mirroring contemporary practical understandings of the military's core roles – hence serving as a reflection of states’ civil-military relations. This being said, there are also several tasks, such as warfighting or epidemics-control, which have been given less space in the official documents, but which we have developed here with the help of the academic literature. Drawing on all these different sources, we have thus inductively arrived at three core roles: (collective) defence, collective security, and aid to the nation with the following subroles and tasks supporting them: warfighting, military assistance, international crisis management, national disaster relief, support to internal security forces, and epidemic support (see Table 1).Footnote 39

Table 1. Military roles and tasks.

(Collective) Defence

National defence, understood as territorial defence against external state aggressions, remains the ultimate justification for national armed forces, both in how military personnel view their role and in the expectations their societies have of them, reflected in the official documents.Footnote 40 Yet, while the defence of national territory as the core organising principle for the military temporarily diminished in importance in the early post-Cold War decades, it has gained traction during the past few years, in the wake of Russia's annexation of Crimea, but also related to the Global War on Terror.Footnote 41

All the official documents analysed for this study identified the defence of national territory and the safeguard of national sovereignty and independence as the main role of the military. There were nevertheless obvious differences in the way that this primary role was formulated. Smaller states stressed for example their membership and loyalty to an international organisation, showcasing the importance of coalitions and allies for national territorial defence, while collective defence was most clearly manifested in NATO allies’ evocation of Article 5.Footnote 42 A heightened focus on national territorial defence in the Baltic and Scandinavian states was also observed both in the doctrine and structure of the Defence and the number of multilateral military exercises undertaken in recent years. Sweden's reintroduction of military conscription in 2018, after a mere eight years of voluntary services has, for example, been accompanied by a law proposal for a total defence concept similar to Norway's, resting on civilian and military cooperation.Footnote 43 In the same vein, the Aurora exercise in 2018 in Sweden gathered several larger allies including the US, Germany, and France and was the first military exercise focused on national defence in Sweden since the 1980s. As such, it served both as an important interoperability exercise between allies, and as a symbolic deterrence function.Footnote 44

These developments notwithstanding, the past three decades have mainly been characterised by a strong focus on expeditionary missions, either deployed to contexts of (irregular) warfare in an effort to quell violent non-state organisations, and thereby also defend the state, or to international crises to maintain Collective Security. We have opted to put the task of warfighting under the role of (Collective) Defence, while International Crisis Management falls under the role of Collective Security.

Warfighting and irregular warfare

One of the military's main tasks is the management and implementation of organised violence,Footnote 45 most clearly exemplified in the conduct of war. Here, we have defined role as a broad and enduring purpose, whereas a task is an action to fulfil a role. From this perspective, warfighting can be seen as a task that is needed to fulfil the role of national defence. It is thus not something that militaries do constantly, yet when needed, they will perform this task in order to play its role as a national defender. In certain contexts where a state has engaged its armed forces in warfare during a longer period of time, the task of warfighting can, however, be transformed into a role. For states like the US, for example, its involvement in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq where coalitions of allied forces have engaged in protracted warfare against non-state actors, warfighting may be understood as a role. Hence, while war metaphors have multiplied in recent years to describe events that do not constitute war (such as the war on drugs, or more recently, the war against a pandemic),Footnote 46 states rarely declare war against other states any longer. The absence of waging war as an accepted task is also evident in the official documents, which talk about avoiding war or maintaining peace and stability, but rarely about the task of fighting wars. The US National Defence Strategy from 2018 touches upon the topic by stating as one of its objectives to: ‘build a more lethal force’, but at the same time writes: ‘the surest way to prevent war is to be prepared to win one’, thereby simultaneously emphasising the aim to avoid wars. Fighting wars is thus a practice that has become taboo to talk about, yet it remains an aspect of contemporary international relations, which is firmly rooted in the military's domain, with both empirical and ideational consequences.Footnote 47

Warfighting takes different forms, depending on the context, the actors and the aim. Since the end of the Cold War, Irregular Warfare (IW) appears as the most prevalent form of contemporary warfare, with some authors arguing that we are in an ‘era of perpetual irregular warfare’.Footnote 48 IW is understood as a ‘complex, “messy”, and ambiguous social phenomenon that does not lend itself to clean, neat, concise, or precise definition’.Footnote 49 Put simply, it is a mode of armed conflict that takes place between non-state actors and/or a state armed force where the aim is to win or diminish population support.Footnote 50 As such, the population is often understood as the centre of gravity of irregular warfare, and psychological concepts such as credibility and legitimacy are important to field success.Footnote 51 While the concept of ‘winning hearts and minds’ dates back to colonial times and as such, hardly is a new phenomenon,Footnote 52 in post-Cold War democracies, an increasing risk aversion by populations often entails not only winning hearts and minds of local populations to win wars, but also of the domestic community whose support is needed to sustain operations. Perhaps more so in contemporary warfare than in previous eras then, the civil-military relationship stands in focus both for the conduct and outcome of wars.

This development is interlinked with the type of operations that falls under IW, such as counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations, and more recently efforts to counter cyberattacks and disinformation, which in turn have put new demands on both internal and external security forces to collaborate, restructure, and reform. Both of the former types of operations have been subject for debates about whether they actually constitute warfighting or not, with many militaries considering that it does not. Fighting a non-conventional enemy that infiltrates, influences, and collaborates with the civilian population, requires new and innovative force structures, technologies, methodologies, and mindsets of the state armed forces. Two developments in particular stand out here: the first is the restructuration of the armed forces following the attacks in 2001, towards smaller and more agile expeditionary forces, and the second is the more recent focus on cyber capabilities and improved (artificial) intelligence. The first restructuration of the military to better fight insurgencies and terrorism, meant a stronger focus on creating small and flexible units, adapted to IW, which could rapidly be deployed abroad.Footnote 53 This development towards IW, where both non-state forces and state militaries use small units in non-conventional ways, has brought about a growth in special operations forces across the international system, gradually restructuring the armed forces towards a more heavy reliance on small elite forces, due to their rapid deployment, ‘clandestine nature, lethality and comparatively small footprint’.Footnote 54 Small, independent units have been prevalent in expeditionary missions falling under the role of Collective Security, as we will see below.

While this development is not mirrored in the more recent documents we examined, the second relating to hybrid threats and cyber capabilities is evoked in most of the strategies and defence papers, calling for more and better intelligence, technologically improved cyber capabilities – for the militaries that have some – and a stronger capacity to detect and deter hybrid threats more broadly. In France most recent strategic update for example, the creation of a cyber defence, a cyber defence strategy, and a doctrine on offensive cyber, are detailed.Footnote 55

Collective Security

Maintaining a stable, secure, and rule-based international order is one of the roles most frequently mentioned for the armed forces in the official documents examined. Such a role includes international crisis management (often in the shape of peacekeeping) and military assistance missions, both of which can take different forms and when protracted over time, can transform into roles. Troop contributions to UN and AU peace operations are among the most common types of international crisis management, but ad hoc coalitions and EU operations also figure in this category. Military Assistance (MA) is a broader category of activities that are all centred on security cooperation. It includes efforts to man, train, equip, and employ foreign forces with the common aim of improving the capacity and quality of a recipient state's coercive institutions,Footnote 56 or fostering democratisation efforts by helping to develop merits-based institutions.Footnote 57 By definition then, military assistance often entails an asymmetric relationship, where the provider role often is reserved for militaries from developed states with significant military capabilities.Footnote 58

Military Assistance

The activities included under this category range from bilateral ‘train & equip’ programmes, to joint operations between several different states, aimed at increasing regional interoperability, to multilateral Security Sector Reform processes, which go beyond purely MA to initiatives within the justice or internal security domain. Yet, as the importance of counterterrorism operations have increased in response to the proliferation and expansion of terror groups in Iraq, Syria, and West Africa, the emphasis has again tilted heavily towards building strong and effective militaries fast, at times relegating the development aspect of these types of partnership programmes to the side.Footnote 59 Especially since 2015, as Europe faced both increased terror attacks domestically and an unprecedented refugee crisis, building capable militaries in weak states, able to neutralise terrorist groups, has gained importance for Western states, what some authors have called ‘two sides of the same coin’, referring to the idea that international military activities are a way to defuse existing or potential national security threats on foreign territory.Footnote 60 The US states, for example, that supporting relationships to address significant terrorist threats in Africa is a priority: ‘we will focus on working by, with, and through local partners and the European Union to degrade terrorists; build the capability required to counter violent extremism’,Footnote 61 while the UK's integrated review states that they ‘will create armed forces that are … engaged worldwide through forward deployment, training, capacity-building’.Footnote 62 This type of MA could both fall under the role of Collective Defence, given that the aim is to prevent terrorist organisations from taking root in partner states, and under Collective Security as it is a means to build and maintain international security, thus illustrating the overlap between the two categories.

These MA, or advisory missions, are often conducted by Special Forces Units, as they require the forces to adjust to dynamic and diverse conditions by ‘drawing on a range of cultural tools, including warrior, peacekeeper-diplomat, subject matter expertise, leadership, innovation, and other tools to succeed’.Footnote 63 Mirroring their own military restructuring priorities, Western states have often focused on building expeditionary capacities in host states, resulting in an emphasis on building small and professional units that can deploy rapidly, thus expanding the importance of various types of Special Operations Forces units to the host states as well. More targeted MA can also include pre-deployment training for peacekeeping contribution, which has become a popular type of military assistance since the early 2000s, when a shift in troop contributing states from mainly Western to Southern states occurred.Footnote 64 This focus on restructuring and building the capacity of small forces has thus not only been justified by referring to counterterrorism purposes, but also for improving peacekeeping capacities.Footnote 65

International crisis management

International crisis management refers to all of the instances in which national military forces are deployed abroad to help solve a crisis. It includes peace operations, disaster relief, and humanitarian aid missions, and this task is, as the previous, performed primarily through expeditionary missions, often in collaboration with other national forces. Although the military has been present in international crisis managements operations before the end of the Cold War, it is not until the 1990s that peacekeeping, which is the most important subcategory here, takes off as a dominant practice in international relations, with the UN as the main actor, planning, authorising, and deploying peacekeeping troops.

This growth in peace operations arrived at a time when armed forces increasingly had to justify their existence,Footnote 66 and one way of building trust and maintaining a relatively prestigious position in society has been to broaden the traditional military role to include functions such as peacekeeping, disaster, and humanitarian relief.Footnote 67 In spite of a change in troop contribution to peacekeeping missions from Western to Southern states, with Africa and Asia making up over two-thirds of UN peacekeeping troops,Footnote 68 this remains one of the core tasks identified in most of the official national security documents. It is nevertheless framed in a variety of different ways, either combined with crisis responses more generally or with the aim to promote peace and stability and uphold international order.Footnote 69 It is also one of these tasks, which for some militaries – so-called ‘peacekeeping armiesFootnote 70 – has transformed into a role, with a broad and enduring purpose, where the armed forces’ raison d’être, training, and structure are strongly linked to its role as an international peacekeeper. While some Western militaries, like Canada, took on strong peacekeeping roles during the 1990s, most of the ‘peacekeeping armies’ today are states from the Global South who are repeatedly found in the top ten troop contributing lists to UN and AU missions.

The military's role in peace operations has put new, and often contradictory demands on soldiers. Whereas the military profession's core function is managing and implementing violence,Footnote 71 peacekeepers need to prevent it by using as little violence as possible. These demands put a heavy burden on the military, as they contrast with the traditional military way of operating, where clear-cut goals and standard operating procedures are the norm.Footnote 72 Two contemporary trends have softened, but also complicated, these contradictory demands: first, as forces are increasingly sent into conflict theatres where peace is still to be made, peacekeeping missions are today often resembling traditional combat missions.Footnote 73 The proliferation of stabilisation mandates and peacekeeper casualties are both signs of this development. Second, as society evolves, military virtues are gradually being altered to reflect new ideals and requirements consistent with their contemporary roles, where communication skills and flexibility – aspects consistent with the peacekeeping role – are valued.Footnote 74 These trends, although contradictory in between themselves as one development draws towards more combat oriented missions, and the other towards a need for more diplomatic and communicative skills, can both contribute to reduce ambiguous demands on soldiers and at the same time reinforce them, depending on the mission and the context.

Aid to the nation

One of the most marked changes in terms of roles for the military in the twenty-first century, is its broadened domestic role. Much in line with what Janowitz predicted decades ago,Footnote 75 the military has taken on constabulary tasks alongside the police, as transnational threats multiply and the boundaries between the realms of internal and external security are blurred.Footnote 76 While some domestic missions have a long history, they have assumed a new urgency as subnational threats have grown, either reinforcing or expanding older roles, or pushing the military into new roles.Footnote 77 Here we have identified three tasks in the domestic sphere that stand out as the most important in the contemporary context: natural or man-made disaster relief, military support to internal security forces, and support during epidemics.

National disaster relief

In his book, Building Democratic Armies, Zoltan Barany asserts that: ‘the only legitimate internal role for the army is to provide relief after natural disasters’.Footnote 78 Its hierarchical structure, specialised roles, and the fact that they are geared for rapid emergency mobilisation and response make the military a valuable tool for governments in disaster struck states.Footnote 79 The military is expected to provide relatively extensive disaster relief to communities hit by natural disasters such as hurricanes, floods, or forest fires, and may become involved in a variety of activities, ‘including search-and-rescue missions, mass feeding and shelter operations, emergency medical treatment, and maintenance of order’.Footnote 80 Some states are more vulnerable to certain types of disasters than others. In Japan's Defence document, for example, there is a paragraph dealing with earthquake prevention dispatch and nuclear disaster relief dispatch, reflecting its history and geographical vulnerabilities.Footnote 81 The disaster relief also includes man-made disasters such as chemical, biological, or nuclear attacks, where tasks may include extensive clean up.Footnote 82 In the US, the disaster relief provided by the military in the wake of Hurricane Katrina is a case in point here,Footnote 83 just as the military support in Czech Republic during the flooding that hit the country in 1998 and 2002.Footnote 84 Disaster relief is a long-standing task that the military is expected to perform in most states, which is also reflected in the official documents examined, yet it is rarely transformed into a role, given its ad hoc nature.

Military support to internal security forcesFootnote 85

The military has increasingly been used in various domestic counterterrorism activities in the past decade, supporting the police by patrolling cities and public places such as airports and train stations. This development has intensified in European capitals in recent years as terror attacks have multiplied. Domestic military operations such as operation Sentinel in France and operation Vigilante Guardian in Belgium, are examples of this, both constituting responses to terrorist attacks on national territories.Footnote 86 As traditional distinctions between crime, terrorism, and war are fading, the military has also increasingly been used for immigration control and relatedly for fighting transnational criminality, epitomised in the concept of ‘war on drugs’.Footnote 87 In the Colombian Defence and Security document form 2019, for example, dismantling organised crime is stated as an objective for both police and military forces, reflecting the blurred boundaries between the two, but also how different states are vulnerable to distinct types of threats.Footnote 88 A law adopted in 2017 in Mexico, for example, expanded military authority in an effort to strengthen the military's role in fighting organised crime by granting them new authority to conduct investigations,Footnote 89 while in Brazil, the military has increasingly been used in long-lasting Guaranteeing Law and Order operations to fight gang criminality and quell riots in favelas.Footnote 90

Epidemics support

The military is also often tasked with a role that up until recently appeared relatively marginal in most societies: support to civilian authorities in case of epidemics or pandemics. Yet, the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa in 2014 prompted an expanded role for the military in fighting the epidemics.Footnote 91 This withstanding, there are relatively few of the examined official documents that mention epidemics specifically, however one exception is the German White Paper from 2016, which devotes a paragraph outlining the need to reinforce prevention and improvements of coordination and crisis management capabilities.Footnote 92 More recently, the 2020 outbreak of COVID-19 has pushed the military into focus for its extensive support to civilian authorities in handling the pandemic.Footnote 93 In European states, the military have constructed field hospitals, provided medical personnel and equipment, supported the building of infrastructure, supervised and planned logistics,Footnote 94 and in some cases, like in Belgium, military personnel were called upon to provide extra personnel in the heavily affected retirement homes where ordinary personnel had fallen sick.Footnote 95 The armed forces have thus been used as a parallel or substitute provider of state goods – such as medical care and provision of intrastucture such as temporary clinics – in support of government departments.Footnote 96

The military's role during epidemics and pandemics is prescribed in most of the official documents analysed here. In most European states, this military support is not threatening the civil-military balance, as other state institutions are capable of maintaining their authority in respective domains. Yet, in some states with important precedents of military rule and relatively nascent democratic structures, the military's prominent role during the pandemic may have wider implications, which outlast the course of the pandemic.Footnote 97 In case the military is performing unpopular tasks, such as enforcing the quarantine, or preventing civilians from doing what they feel they need to do, it may also result in deteriorating civil-military relations.Footnote 98

Above we have identified three core roles for the military in contemporary society, with important associated tasks. It is clear that while these roles and tasks cover a broad range of militaries’ activities, there are many others that are not included. We did not discuss the military's social role in nation building,Footnote 99 military diplomacy, or military intelligence more broadly for example. While the latter two are roles that may be of less importance in certain states than in others and are less likely to affect civil-military relations more directly, the military's role in nation building is clearly one function that is deeply related to the civilian sphere. Yet, while this role may be prominent in some states,Footnote 100 notably those that still have conscription, we see this as a role, which, in general, is less important for militaries across the world today because of the professionalisation of the military and the dissociation from civilian society, which has followed from this. We discuss this further in the following section, which can be characterised as meta-analysis of the above-mentioned findings, extrapolating on the impact of changing military roles on emerging patterns in civil-military relations.

Changing civil-military relations

The past three decades’ changing roles for the military have had significant impact on the configuration of civil-military relations in different ways. Here, perhaps more than in the previous sections, it is important to underline the vast differences in civil-military relations between various states, even when the latter are defined as industrialised democracies belonging to the same international organisation (in this case OECD). Chile and Sweden are clearly not sharing the same type of civil-military relations, nor are Israel and Norway. We are, however, not pretending to take into account national particularities, but to identify general trends and developments that affect the majority of states. From this perspective, we have discerned two interlinked trends in military roles that affect civil-military relations: increased visibility due to blurred boundaries between internal and external security forces and high levels of trust. Together, these trends imply a stronger possibility for the military to get involved in politics, which is discussed in the remainder of the section.

The first trend concerns increased visibility of the military. In spite of the global transformation from a conscript to a voluntary recruitment system, leading to the military being more distinct from society,Footnote 101 in recent years the military has acquired broader and more visible domestic roles.Footnote 102 The change from a conscript army to a voluntary force, which took place in many states at the end of the Cold War, distanced the military from society. As a result, the military became less visible to the average civilian in the 1990s.Footnote 103 Fewer people know someone who served or has served in the military, as the pool is smaller, and the recruitment system has changed.Footnote 104 Yet, as the military has taken on more important domestic roles in the past two decades,Footnote 105 such as supporting internal security forces in counterterrorism activities and responding to natural disasters and pandemics, it has also acquired highly visible roles in contemporary societies.Footnote 106

Observers disagree, however, on whether the broadened domestic role result in civilians having a lower or higher esteem for the military. While some argue that the esteem may decrease in cases where the military ‘is performing unpopular missions at home’,Footnote 107 others contend that the military's support during natural disasters is one of the main causes of trust in the institution,Footnote 108 thus also likely to increase the esteem. The domestic counterterrorism role, which, in states like France and Belgium, has been most visible through militaries patrolling the streets, was supported by a noticeable 78 per cent of the Belgian population in the years immediately following the terrorist attacks in the state.Footnote 109 This suggests that the military's expanded internal focus has increased its popularity domestically – at least in some cases. This support reflects a broader trend of an increased trust and support for the military institution globally.

A second trend is the high levels of public trust that militaries enjoy worldwide, according to global surveys.Footnote 110 In World Values Survey from 2010–14, 63.6 per cent of the respondents from the total sample expressed trust in their national armed forces, with only universities ranked higher (66.2 per cent) and churches in the third place.Footnote 111 In Western Europe, Latin America, and the US, trust in the military exceeds trust in other institutions, with a median of 76 per cent, with France, whose military has been highly visible during the past few years in domestic counterterrorism activities, topping with 84 per cent of the respondents trusting their military.Footnote 112 It is not clear whether these high figures are directly related to the broadened domestic roles for the military, yet they do represent an upward trend in the popularity and trust of the military. In addition, using the case of France in 2015–16, Vincenzo Bove et al. have shown how the military's involvement in politics during operation Sentinel was the consequence of a ‘pulling’ mechanism by politicians, which resulted in increased autonomy, resources, and bargaining power for the French military, evoking further questions about civil-military balance when the military is used for domestic purposes.Footnote 113

Somewhat counterintuitively, however, this popularity does not always translate into a personal willingness to serve in the military or to encourage one's child to serve.Footnote 114 Ronald R. Krebs and Robert Ralston have recently shown, through popular surveys in the US, that the image of the soldier-citizen by no means is dead, with many respondents still subscribing to an idealised image of soldiers and officers as self-sacrificing patriots.Footnote 115 Illustrating this trend, French operation Sentinel, for example, ‘greatly improved recruitment rates and the legitimacy of the military to exceptionally high levels’.Footnote 116 Yet, this trend is not consistent across industrialised democracies, or even in states that have had similar domestic CT operations such as France. Soaring recruitment rates in combination with a large number officers retiring simultaneously in the Belgian armed forces have for example led to a pending personnel crisis.Footnote 117 This may be linked to a general sociocultural shift during the past decades, whereby individual rights have increasingly been emphasised, and traditional values, which used to be prominent in the military institution, such as work ethic and religious values have taken a backseat to working conditions and financial and material incentives.Footnote 118 Or as John Allen Williams described it: ‘Many view the military as they might a Rottweiler: they are happy for the protection, but do not want themselves or anyone in their family to become one.’Footnote 119

Together, these two trends raise questions concerning governance of the military and points to complex issues regarding accountability and legitimacy. As such, they provoke classical questions about the military's relationship to society in a swiftly changing context.Footnote 120 Many authors have already questioned the accuracy of Huntington's strict separation between the military and society. Morris Janowitz, Rita Abrahamsen, and Douglas L. Bland, among others, point to a closer relationship between the two, where borders at times are blurred.Footnote 121 In recent years, as the military has acquired new domestic roles closer to the civilian sphere, and as politicians in states that previously respected the military's apolitical nature, have attempted to politicise the military, this debate has resuscitated.Footnote 122

There are two sides to this development: on the one hand, the military is more inclined to take on a political role, and on the other hand, politicians increasingly pull the military into the political sphere,Footnote 123 raising questions regarding who should govern in each domain. New research, building on surveys, shows that a significant number of military personnel do not believe that they should be apolitical,Footnote 124 confirming a trend that military officers are prone to take on policy advocate, rather than policy adviser roles, in an effort to have greater influence on politics.Footnote 125 At the same time, some politicians in countries that previously have respected the civil-military division, notably President Trump and President Bolsonaro, have used the military for political purposes, thereby upsetting the civil-military balance while putting the military in a difficult position.Footnote 126

While the practices of politicising the military and militarising politics are not new phenomena in many states (most notably African countries that have witnessed a high number of military coups over the past decades),Footnote 127 it is a relatively recent trend in some Western states. This development occurs in a period where many previously military functions have been civilianised and where civilians are increasingly integrated in the military, thus blurring the boundaries between the two spheres further.Footnote 128 Whereas some observers take a clear stance against the military's involvement in politics,Footnote 129 others open up for a new debate about the limits and conditions of such involvement in order to update and adapt principles to contemporary challenges.Footnote 130

Conclusion

We started off this article by defining military roles and tasks as socially constructed, reflecting contemporary civil-military relations. In our inductive analysis of the military's core roles and tasks, we identified three core roles, (collective) defence, collective security, and national security, with several important tasks falling under each of the headings. While recent trends suggest that the military will again need to prioritise national defence and deterrence in an increasingly unstable environment, they also need to maintain duties in international crisis management to prevent this environment from deteriorating further. This analysis has thus confirmed that today's military is a highly versatile organisation, with a broad spectrum of roles and tasks that it is expected to take on in different scenarios. Or, as Rita Brooks argues: ‘We need an army, in other words, that can do everything, everywhere – in a world where war may be everywhere, and forever.’Footnote 131

Some of these newer tasks contradict traditional ones and can bring about tensions and provoke questions about identity. The peacekeeping task is a case in point here, where the soldier-warrior identity is, at least partially, to be replaced by the soldier-diplomat identity, depending on the mission. Other newer tasks such as domestic counterterrorism activities, blur established boundaries between internal and external security forces’ responsibilities, while the military's role in pandemics recently became an active and highly visible task with the COVID-19 outbreak.Footnote 132 Analysing how these roles and tasks affect civil-military relations, we have pointed to a paradoxical development whereby the military is both more visible and more distant to the civilian population due to increased demands for (visible) national security tasks and professionalisation.

The military has thus far responded to demands of legitimisation and adapted to new security threats by changing the force structure, acquiring new competencies and taking on broader roles. This has, according to recent global surveys, resulted in increased trust and popularity in the military institution. Yet in spite of this growing popularity, recruitment is increasingly difficult in many Western societies that value individual liberties and favourable working conditions, aspects which up until recently have not belonged to the military's assets. Recruiting individuals from groups that so far have been underrepresented in the military, has also brought questions about employment conditions to the fore, including work-life balance, deployment length, and competitive salaries.Footnote 133

Efforts to recruit more broadly are, however, not only related to a ‘numbers’ game’, but also to the more functional demands of the military to adapt to new threats, where a more representative and inclusive force is seen as operationally more effective.Footnote 134 While such demands have been met with a relatively broad support from the top echelons of military institutions, significant internal resistance remains, reflecting the conservative character of the armed forces. Questions about how to best integrate such underrepresented groups without disrupting cohesion or putting any added burden to already small minorities within the organisation,Footnote 135 remain crucial to address to avoid internal tensions and maintain operational effectiveness. At the same time, altering the composition of the armed forces, whether induced by operational demands or societal pressure, will provoke new perspectives on civil-military relations.

The diversity and proliferation of military roles and tasks reveal both internal and external tensions and questions. Internal tensions because the institution is expected to take on more responsibilities with fewer people, as the professionalisation and downsizing post-Cold War has reduced the size of the military. The strong focus on Special Operation Forces has also produced internal tension, as a small elite unit is required to be highly skilled and flexible in a variety of domains, whereas other, more traditional units have had to take a back seat until very recently, when Great Power competition brought back attention to the conventional military. The higher number of civilians integrated into the military is also a factor that can provoke tensions relating to cohesion and identity if roles and tasks are not clearly divided, and if working conditions create imbalances. These internal tensions can destabilise both the military identity and the cohesion of the forces if open discussions regarding the expectations by external actors and internal role conceptions do not result in clear divisions of labour, responsibility, and accountability, with adequate resources to fulfil the roles.

This article has identified and analysed the military's core roles in today's society and reflected over its consequences for civil-military relations. We see this work as a possible new starting point for in-depth studies on the military's core roles, the current challenges in civil-military relations or as a background against which studies on the need for greater diversity and representation can build upon. This analysis also provides a basis for research looking into the militarisation of society or the politicisation of the military,Footnote 136 both aspects that deserve attention and examination in further work. Ultimately, in this article, we have shown that while the military remains a highly hierarchical and stable institution characterised by continuity and tradition, it has also proven to be malleable in the face of having to adapt to new circumstances, and to the society it is tasked to protect, in order to remain relevant. Roles and tasks are thus likely to continue to evolve, to reflect contemporary understandings of what and whom the armed forces are for.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers, the editors Christoph Harig, Nicole, Jenne and Chiara Ruffa, and the contributors of this Special Issue for constructive comments on earlier drafts. We would also like to thank Sven Biscop, Charlotte Isaksson, Alexander Mattelaer, and Jonathan Schroeder for useful input on earlier versions of this article.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2021.27

Nina Wilén is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science, Lund University, Sweden, and Director of the Africa Programme, Egmont Institute, Brussels.

Lisa Strömbom is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science, Lund University, Sweden.

Appendix

National Documents

Argentina

Argentina Ministerio de la Defensa, Libro Blanco de la Defensa 2015 (2015).

Argentina Ministerio de Defensa, Libro Blanco de la Defensa (2010).

Australia

Australian Government Department of Defence, Defence White Paper (2016).

Austria

Republik Österreich Bundesministerium für Inneres, Austrian Security Strategy: Security in a new decade-Shaping security (2013).

Austrian Parliment, Security and Defence Doctrine (2001).

Belgium

Belgian Mission Statement Defense, Déclaration de mission de la défense et cadre stratégique pour la mise en condition (2019).

Belgische Minister van Defensie, De strategische visie voor Defensie (2016).

Brazil

Brazil Ministry of National Defense, National Strategy of Defense (2017).

Canada

Canada Minister of National Defence, Canada's Defence Policy (2017).

Chile

Chile Ministerio de Defensa Nacional, Libro de la Defensa Nacional de Chile (2017).

Colombia

Gobierno de Colombia, Política de Defensa y Seguridad PDS (2019).

Colombia Ministry of National Defense, Policy for the Consolidation of Democratic Security (2007).

Czech Republic

Czech Republic Ministry of Defence, The Long Term Perspective for Defence 2035 (2019).

Czech Republic Ministry of Defence, The Long Term Perspective for Defence 2030 (2015).

Czech Republic Ministry of Defence, Defence Strategy of the Czech Republic (2012).

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

Republic of Korea Ministry of National Defense, Defense White Paper 2018 (2018).

Denmark

Danish Government, Danish Defence Agreement 2018-2023 (2018).

Estonia

Estonia Minister of Defence and Defence Forces, Estonian Military Defence 2026 (2017).

Government of Estonia, National Security Concept 2017 (2017).

Estonia Minister of Defence and Defence Forces, Estonian Long Term Defence Development Plan 2009-2018 (2009).

Finland

Finland Prime Minister's Office, Government's Defence Report (2017).

France

France Ministère des Armées, Actualisation Stratégique (2021).

Journal Officiel de la République Française, LOI no 2015-917 du 28 juillet 2015 actualisant la programmation militaire pour les années 2015 à 2019 et portant diverses dispositions concernant la défense (July 29 2015).

France Ministère de la Défense, Livre Blanc Défense et Sécurité Nationale (2013).

France Ministère des Armées, Le rôle du ministère des Armées (2008), available at: {https://www.defense.gouv.fr/portail/ministere/le-role-du-ministere-des-armees}, accessed 25 January 2021.

Germany

The Federal Government of Germany, White Paper on German Security Policy and the Future of the Bundeswehr (2016).

Greece

Government of Greece, White Paper for the Armed Forces (1997).

Hungary

Csiki Varga, T., ‘Hungary's new National Security Strategy – A critical analysis’, Institute for Strategic and Defence Studies, ISDS Analyses 2021/1 (2021).

Hungary Ministry of Defence, Hungary's National Military Strategy (2012).

Government of the Republic of Hungary, The National Security Strategy of the Republic of Hungary (2004).

Iceland

Government of Iceland, National Security Policy for Iceland (2016).

India

India Headquarters Integrated Defence Staff, Joint Doctrine Indian Armed Forces (2017).

Ireland

Government of Ireland, White Paper of Defence Update 2019 (2019).

Israel

HARVARD Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, ‘Deterring Terror: How Israel Confronts the Next Generation of Threats. English Translation of the Official Strategy of the Israel Defense Forces’, Belfer Center Special Report (2016).

Italy

Italy Ministry of Defence, White Paper for international security and defence (2015).

Japan

Japan Ministry of Defense, Defense of Japan 2019 (2019).

Japan Ministry of Defense, Defense of Japan 2014 (2014).

Latvia

Republic of Latvia Minister of Defence Media Relations Section, ‘Seima approves the National Defence Concept’, Minister of Defence of the Republic of Latvia (2020) available at {https://www.mod.gov.lv/en/news/saeima-approves-national-defence-concept#:~:text=Aim%20of%20the%20comprehensive%20national,non%2Dgovernmental%20and%20private%20partnerships.}, accessed 20 May 2021.

Republic of Latvia Ministry of Defence, The State Defence Concept (2012).

Lithuania

Government of Lithuania, National Security Strategy (2017).

Republic of Lithuania Minister of National Defence, The Military Strategy (2016).

Luxembourg

Luxembourg Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, Luxembourg Defence Guidelines for 2025 and Beyond (2017).

Mexico

Estados Unidos Mexicanos, ‘Decreto por el que se aprueba el Programa Sectorial de Defensa Nacional 2020-2024’, Diario Oficial de la Federación (2020).

Gobierno de México, Estrategia Nacional de Seguridad Pública (2018).

Gobierno de México, Ley Orgánica del Ejército y Fuerza Aérea Mexicanos (2018).

Netherlands

The Netherlands Ministry of Defence, 2018 Defence White Paper: Investing in our people, capabilities and visibilities (2018).

New Zealand

New Zealand Ministry of Defence, Defence Capability Plan 2019 (2019).

New Zealand Ministry of Defence, Defence White Paper 2010 (2010).

Norway

Norwegian Ministry of Defence, The defence of Norway: Capability and readiness. Long Term Defence Plan 2020 (2020).

Norway Ministry of Defence, Future Acquisitions for the Norwegian Armed Forces 2014-2022 (2014).

Norway Ministry of Defence, Strategic Concept for the Norwegian Armed Forces 2004 (2004).

Norway Ministry of Defence, The Further Modernisation of the Norwegian Armed Forces (2004).

Poland

Poland Ministry of National Defence, The Defence Concept of the Republic of Poland (2017).

Poland National Security Bureau, White Book on National Security of the Republic of Poland (2013).

Portugal

República Portuguesa Defensa Nacional, Strategic Concept of National Defence (2013).

Slovak Republic

Slovak Republic Ministry of Defence, Defence Strategy of the Slovak Republic (2021).

Slovak Republic Ministry of Defence, White Paper on Defence of the Slovak Republic (2016).

Government of the Slovak Republic, Defence Strategy of the Slovak Republic (2001).

Slovenia

Republic of Slovenia Ministry of Defence, Defence White Paper of the Republic of Slovenia (2020).

Spain

España Presidencia del Gobierno, Directiva de Defensa Nacional 2020 (2020).

España Presidencia del Gobierno, Estrategia de Seguridad Nacional 2017 (2017).

España Presidencia del Gobierno, The National Security Strategy: Sharing a Common Project (2013).

Sweden

Sveriges Regering, Regeringens proposition 2020/21:30 Totalförsvaret 2021-2025 (2020).

Sweden Ministry of Defence, Sweden's Defence Policy 2016-2020 (2015).

Switzerland

Swiss Armed Forces, Missions (2021), available at: {https://www.vtg.admin.ch/en/news/einsaetze-und-operationen/militaerische-friedensfoerderung/missionen.html}, accessed 16 February 2021.

Government of Switzerland, White Paper on Neutrality (1993).

Turkey

Republic of Turkey Ministry of National Defence, “Mission”, Turkish Armed Forces (2021), available at: https://www.tsk.tr/Sayfalar?viewName=Mission, accessed 16 February 2021.

United Kingdom

HM Government, Global Britain in a competitive age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (2021).

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 (2015).

United States of America

U.S. Department of Defense, Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America (2018).