Introduction

The breadwinner model was a typical feature of twentieth-century conservative-corporatist welfare states. According to Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s theory of welfare capitalism, these countries, with social security systems based on collective social insurance, often had low female employment rates, partly because of the traditional attachment of trade union members and employers to the idea of family wages.Footnote 1 The benefits and protections of the social welfare state were linked to having a full-time job, and spouses were insured through their working husbands. As a result, married women often had no financial incentive to look for work outside their homes, and they were often inactive in the labor market. The heyday of the breadwinner model was a low point in the labor force participation of women.

Nevertheless, women’s employment rates increased in the mid-twentieth century, posing a challenge to breadwinner-based economies. In part, it was the rise of part-time work that contributed to the rising employment rate of women in the twentieth century. When they emerged in the 1950s, part-time jobs were often portrayed as an “extra” for stay-at-home women. The growth was fueled by individual entrepreneurs in the temp industry who capitalized on the desire of married women to have a “side income.” The first major temporary employment agencies, Manpower, and Kelly, which emerged in the United States, boosted the image of the “side job” in their recruitment campaigns with statements that these women “have no illusions about a great career.”Footnote 2 As women’s employment rates began to increase, scholars have questioned whether these part-time jobs then became an “integrative device” for women who would otherwise be inactive in the labor market, and thus a stepping-stone to full-time employment, or whether the rise of part-time employment was rather an example of the marginalization of female labor, a trend that started at least at the beginning of the nineteenth century but saw a continuation here.Footnote 3

Some scholars see the growth in part-time jobs in the second half of the twentieth century as a process that developed autonomously and independently in different countries.Footnote 4 In this view, the emergence of part-time work is more a development of the free market, in which employment agencies play an important role, than a result of active coordination through “non-market” relationships.Footnote 5 However, in the postwar period, developments in different countries regarding part-time work were not unrelated; several corporatist organizations monitored the developments in the labor markets of other countries and reacted to this. Statements that the emergence of part-time work was an autonomous process thus tend to overlook the degree of coordination between employers’ organizations and government agencies in the history of female labor force participation.

This article examines the adoption, implementation, and advocacy of part-time employment policy in the Netherlands between 1945 and 1970 and serves as a case study of how employers’ organizations in a corporatist welfare state instrumentalized part-time employment for their own moral economy based in the breadwinner ideology. As part-time work gradually became an element of labor policy that could be transferred from one country to another, several stakeholders in the Dutch labor market adopted employment strategies from employment agencies to make part-time employment a sustainable supplement to the breadwinner model of the corporatist welfare state.

The article first explores the degree to which the male breadwinner model was supported in the Dutch postwar economy. Second, it discusses the shock to employers’ organizations that followed the increase in married women working full-time in the manufacturing industry. Third, using the example of Catholic employers’ organizations, it examines the progressively changing attitudes of employers’ organizations toward working married women and how they warmed up to the idea of part-time employment. Catholic employers are an interesting player, as they were most committed to the breadwinner model, but were also predominantly active in industries where female workers were in high demand. Finally, the article argues that stakeholders in the Dutch economy saw the support of part-time work at home and abroad as the solution to protect the Dutch breadwinner state in the globalizing economy of the postwar era. The article thereby contrasts the initial concerns of Dutch employers about women’s increasing labor force participation with the country’s later international role in advocating part-time work for married women. Ultimately, the article aims to contribute to our understanding of how coordination at the national and international levels has played a role in protecting the breadwinner model from the threat people felt from increasing female employment.

The Ideology of the Male Breadwinner Model

The prevailing view of Dutch labor relations in the period between 1945 and 1970 is that it was “the heyday of the breadwinner model”: a period marked by the “absence of women from the labor market.”Footnote 6 The “standard employment relationship” was the norm, and there was “little diversity in work patterns.”Footnote 7 Even though the roots of the male breadwinner model trace back to at least to the early nineteenth century, the political support for the breadwinner model had never been stronger than in les trente glorieuses, after World War II.Footnote 8 Due to the scholarly focus on the breadwinner model and the support of “the standard employment relationship” in the 1950s and 1960s, little attention has been paid in historiography to alternative employment options in the Dutch labor market in this period. Even in an important study of working women in the 1950s, there is no substantial mention of part-time work.Footnote 9

Indeed, in the 1950s, there was a consensus that the Dutch government had an important responsibility in supporting the breadwinner family. With a specific set of policy measures, politicians seized the moment of reconstruction after World War II to ensure that workingmen could financially support their families with a single job. The government had decided that child benefits—which were initially only paid from the third child onward—were extended to the first two children.Footnote 10 At the heart of the governmental protection of the breadwinner family, however, was the “guided wage policy” (geleide loonpolitiek): the government regulated maximum wage increases, based on the needs of the “standard family” (a man and a woman with two children).Footnote 11 As an influential 1952 report of a governmental committee on the dismissal rule for married female civil servants explained: “A constant concern for justified wage levels will lead to the situation that married women—whose tasks are primarily in the family—will be able to devote themselves fully to this task.”Footnote 12

Dutch industrial relations were characterized by a high level of coordination between employers. It was a coordinated market economy, in which many employers were organized both along denominational lines and in economic sectors.Footnote 13 Support of for the breadwinner model existed in all parts of the Dutch corporatist structure. Even though no legal prohibitions were introduced on hiring married women in the private sector, many employers’ organizations refrained collectively from employing married women. In fact, according to the same abovementioned governmental committee, “the vast majority” of Dutch companies followed the government’s example that no married women were to be employed and that women were fired after marriage.Footnote 14 This rule was, for example, actively enforced at the Tilburg Wool Manufacturers Association.Footnote 15 Trade unions likewise supported the breadwinner model. For instance, the Christian National Trade Union Federation (CNV), the largest Christian trade union, campaigned for a long time for a ban on working women. As its board stated in 1955: “In foreign countries, married women often participate in the production process. We should not go that way!”Footnote 16

There clearly was a moral underpinning to the breadwinner model, as welfare organizations also played a role in supporting the breadwinner family. The deacons of the Reformed churches had established a national network of “family care” that offered help to families when a woman was temporarily unable to fulfill her role as housewife.Footnote 17 As there was no insurance covering the risk of the loss of the care of the non-breadwinner, these organizations were able to help families without women to do care work.Footnote 18 All policies to secure the breadwinner model combined therefore clearly demonstrate the existence of an overarching “moral economy” centered around the ideals of family life and the proper functioning of the labor market.

The centrality of family life in politics and the moral economy of the breadwinner model made the inequality between large and small families a major political theme of the time. The “large family” issue was one of the first topics addressed by the tripartite Social and Economic Council (SER) after it was founded in 1950.Footnote 19 The SER was the foremost important body established to advise the government on social and economic coordination, consisting of union representatives, employers’ organizations, and economic experts: the so-called “crown members.” The SER was created as a way of finding compromise between labor and capital.Footnote 20 However, there were also conflicts surrounding its focus on productivity, and important developments preceded this advice.

The conflict that emerged over the question of whether child benefits should be made dependent on the size of the families, however, made a deep impact. It resulted in the establishment of another important advisory body: the “Family Council.” The board of the Catholic People Party (KVP), which fashioned itself as the greatest advocate of the interests of large families, stated that “the advice of the Family Council could provide the necessary support for a healthy family policy, which is missing in the advice of the SER.”Footnote 21 The Family Council functioned therefore as an explicit counterweight to the SER, which was—according to its critics—too economically oriented.

Where the SER was the foremost body dealing with productivity, the founding of the Family Council reflected the overall emphasis on “the family” in the period.Footnote 22 The breadwinner model and “healthy” family life were thereby the two essential core beliefs of the moral economy dictating both government policy and the interests of the stakeholders in the political debate of the 1950s. The year 1966 can be seen as a turning point, when the SER published a unanimous advice to promote part-time employment opportunities for married women. The explicit goal of the SER’s advice was to think of ways to increase female labor force participation and combat the “women shortage” in several industries.Footnote 23 The SER and the Family Council were also the primary bodies later advising the government and employers’ organizations on making these principles align with the need for increasing participation of married women in the Dutch labor force.

Recruiting Married Women into the Industry

The fact that there was broad political support for the breadwinner model in the 1950s, however, does not imply that all married women were completely inactive in the years after the war. Nor can we assume that there were no alternatives to full-time employment. Although women’s employment rates certainly declined from the nineteenth century, a number of married women still worked in factories, on farms, or from home, depending on the sector in which they worked and the region in which they lived.Footnote 24 The breadwinner model thus never fully became reality, and women indeed significantly contributed to the family income in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 25

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, the labor participation of married women in industry started to increase. The Labor Inspectorate could keep these numbers accurately up to date in their reports, because the Labor Act of 1919 stipulated (§ 67) that married women working in industry had to be in possession of a work permit. The Labor Inspectorate was therefore used to working with the crucial distinctions between married and unmarried women.Footnote 26 From 1935 until 1942, the number of issued permits rose from 8448 to 13,891. The increase can partly be explained by the fact that women took over the work of mobilized men. In other countries, such as Germany and Great Britain, this had already happened during World War I.Footnote 27 In response to this development, the Roman Catholic politician Carl Romme famously advocated a prohibition of married women’s wage work, as he believed that women pushed men out of the workplace; this prohibition never materialized.Footnote 28

After World War II, the number of work permits for married women continued to rise. Between 1947 and 1960, the number increased by almost 200 percent (Figure 1). The number of married women employed in industry formed a large share of the total number of employed women. In 1956, Statistics Netherlands (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek [CBS]) calculated that 51,000 married women were employed, meaning that 73 percent of working married women were employed in the industry in that year.Footnote 29

Figure 1. Work permits issued for married women, 1930–1960.

Source: Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Volksgezondheid. Centraal verslag der arbeidsinspectie in het koninkrijk der Nederlanden. The Hague, 1930–1960.

The reason married women were recruited for industry was partly due to concerns about the large staff shortages that many companies faced after the war. The “women shortage” was, of course, strongly informed by the gendered construction of male and female professions.Footnote 30 Initially, these concerns were mainly related to the declining supply of unmarried girls over the age of fifteen. A 1946 Labor Inspectorate report offered various explanations for this shortage: The first was that girls went to school longer; a consequence of the raising of the compulsory school attendance age to 15 years—implemented during the German Occupation in 1942. Second, the inspectorate believed that girls increasingly preferred supporting their own family households rather than working outside their families. The limited supply of consumer goods was furthermore cited as a reason for girls to no longer need any “extra earnings.”Footnote 31

Per sector and region there were specific causes for the shortage of female workers. There was, for example, a perceived shortage of domestic staff and cleaning help. This problem, long known as the “servant problem,” had increased after many of the foreign girls attracted to those positions were forced to migrate during the war.Footnote 32 Meanwhile, certain industrial sectors suffered from a “women shortage,” too. Before the war, for example, many Jewish girls were employed in the Amsterdam textile industry. Due to the deportation of Jewish citizens, Amsterdam textile manufacturers started to address their worries about a personnel problem after the war. These factories began to recruit workers from the Haarlem textile industry, resulting in severe staff shortages for the textile companies in Haarlem.Footnote 33

One of the solutions to the labor shortage in these branches of industry was to hire married women. As an important example, the chocolate factory of Verkade in Zaandam drew the attention of the Labor Inspectorate in 1947. At the start of this year, about 150 married women were employed at Verkade.Footnote 34 Meanwhile, this initiative slowly began to spread into different industries. In 1951, the inspectorate noted a “strong increase” in the number of married women in factories, due to “the current need to increase production as much as possible.”Footnote 35

Working Hours of Married Women

Some departments of the Labor Inspectorate believed there was a connection between the increase in the labor supply of married women and the increasing wishes for different working hours, especially in the district of Twente, where much of the Dutch textile industry was located:

Many of these married women prefer to work two shifts rather than the regular shift when given the opportunity. The motives for this are: more time off, so that they can take more care of their family and have the opportunity to do groceries during the day.Footnote 36

Despite these remarks, however, it soon became clear that the majority of married women in industry worked full-time.

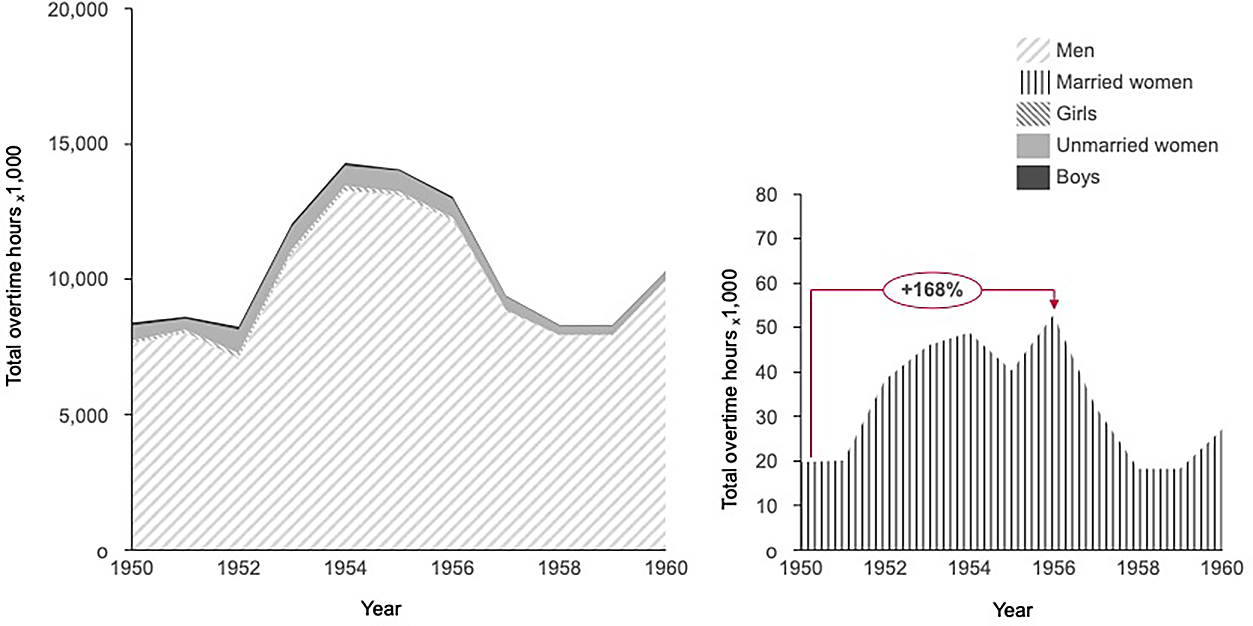

A nonrepresentative sampling by the Labor Inspectorate from 1951 found that the vast majority of 382 married women had a full working week of 48 hours.Footnote 37 In addition, the inspectorate reported increased requests for overtime hours for married women. In fact, the inspectorate’s annual reports show that the number of overtime hours for married women more than doubled between 1950 and 1956 (see Figure 2). Only during the recession of 1957–1958 did this number decrease—as did the number of overtime hours for men. The fact that the decline was less pronounced for men than for women indicates that, when production decreased, married women’s hours of work were cut first.

Figure 2. Total overtime hours by subgroup, 1950–1960.

Source: Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Volksgezondheid. Centraal verslag der arbeidsinspectie in het koninkrijk der Nederlanden. The Hague, 1950–1960.

Several later studies confirmed that most married women in industry worked full-time. A 1956 CBS wage survey among women in industry, for instance, found that 28.5 percent of their sample of women over the age of 25 had an “incomplete day or week job”; hence, 71.5 percent worked full-time.Footnote 38

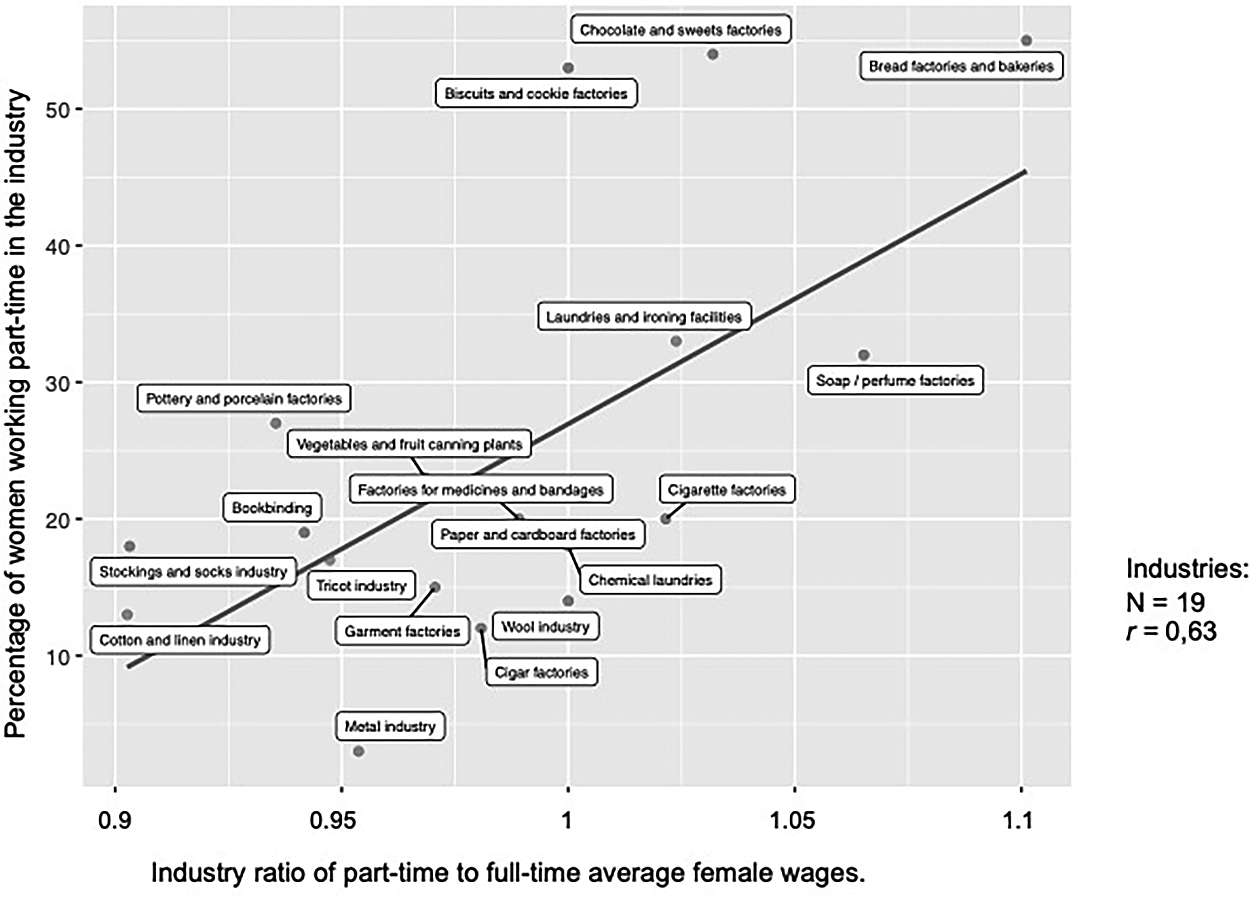

The same survey found a strong positive correlation (r = 0,63) between the industry ratio of part-time to full-time wages of adult women and how many of the adult women worked part-time in the industry.Footnote 39 As Figure 3 shows, in certain industries, such as bakeries and bread factories, the average hourly wages of part-time workers exceeded the hourly wages of women with a full-time appointment, while more than half (55 percent) of the working adult women worked part-time in this industry. In other sectors where part-time employees received a lower hourly wage, such as the cotton and linen industries, however, less than 25 percent of adult women generally worked part-time.

Figure 3. Relationship between industry ratios of part-time/full-time female wages and percentage of women working part-time in the industry in 1956 (for women over 25).

Source: CBS, “Werkgelegenheid”, Sociale Maandstatistiek 5, no. 11 (1957): 349–353.

Overall, these data show a strong positive correlation between pay ratios and part-time employment. Even though the data are based on only nineteen observations (unlikely to be statistically significant), the correlation is interesting, because it might suggest that wages were an incentive for women to work part-time and that certain industries used higher wages to attract women to evening shifts, which were, for example, more common in the food processing industry.

A problem with these different surveys, however, was that there was no shared definition of part-time work. In 1962, the Netherlands Institute for Efficiency (NIVE) also found that around 51 percent of working married women worked full-time.Footnote 40 NIVE, however, employed a definition of a working week of fewer than 35 hours, whereas the CBS population census of 1960 used a definition of 15–30 hours and excluded people working fewer than 15 hours. Based on its definition, CBS estimated that 77 percent of employed married women worked full-time in 1960.Footnote 41

When zooming into a specific branch of industry, it becomes clear that working hours could differentiate between married and unmarried women, but not dramatically. A 1959 survey by the Social Employers’ Association for the Clothing Industry, for instance, showed that unmarried women had a working week of 46.9 hours, while “newly married” and “older married women” worked 42.1 and 36.7 hours on average.Footnote 42 It is likely that some of the women who worked full-time were working from home, but the data made no specifications on this.

The paradox in female labor force participation of the period after World War II was that the number of married women in industry increased, even though the total number of working women decreased. The labor force participation of married women remained exceptionally low in the Netherlands in the 1950s. Yet the increase of full-time working married women in industry was a development in the labor market that clearly came as a shock to Dutch employers’ organizations. As a result, a growing call emerged among ardent supporters of the breadwinner model to respond to this trend and influence the hours that married women worked in industry.

The Shock Effect on Catholic Employers

From 1954, concerns about the development of married women in the workforce were expressed in various employers’ organizations, especially in the clothing industry. In 1954, such employers voiced their worries for the first time to the board of the General Catholic Employers’ Association (AKWV), the umbrella organization for Catholic employers’ organizations. They warned about “the threat that women’s labor will take on a massive character” and the “light-heartedness” with which other employers talked about it.Footnote 43 Soon other warnings followed. A board member of the AKWV expressed his fear that “the drain of mothers from their families” would have major consequences for the upbringing of their children.Footnote 44 Elsewhere the board noted:

On the one hand, this labor almost certainly leads to neglect of the duties of the woman in her household, on the other hand—as experience shows—the presence of married woman in the enterprise very soon increases the moral dangers to herself and her surroundings.Footnote 45

Catholic employers formed an interesting party in the Dutch industrial landscape. The church’s teachings informed their strong commitment to the breadwinner model. Yet many of these employers were active in the industries that had a great demand for female workers, such as the textile and clothing industry. The data from the 1956 housing census show that the male-to-female ratio of people employed in the nonagricultural sector was especially high in the urbanized west, such as Haarlem and in regions dominated by the textile and clothing industries. These were also dominantly Catholic regions, such as the surrounding areas of Tilburg in the south and Enschede in the east.

In 1951, the Labor Inspectorate had already warned that a general inquiry into the family situation of working married women was much needed.Footnote 46 Members of the AKWV shared this belief and stressed that it was important that employers accept their responsibility on this issue. Action by employers was especially needed, as there had been a sectoral shift in women’s employment from agriculture and domestic work to factory work. This was argued by the influential SER member Paul Pels in 1955.Footnote 47 A sectoral shift could indicate that married women were actively recruited for the manufacturing industry. In that case, employers in the manufacturing industry played an important part in attracting married women to industry, members of the employers’ organizations argued.

The spiritual advisers to the Catholic employers’ organization therefore strongly urged individual employers to consider their priorities. Chaplain Bernardus Rohling, for instance, pressed individual employers on this point and called on them to accept their responsibility as members of the church:

Every industrialist [should] consider whether he should observe certain limits with regard to increasing productivity or expanding the business, if he perceives that other important values are compromised … and I assume that Catholic employers accept the Church’s clear teaching that married women have their first and foremost task in the best possible care of their families.Footnote 48

The emphasis on the personal responsibility of employers was also inspired by the employers’ general rejection of central government intervention. Backed by the AKWV board, the employers’ organization in the apparel industry issued its own guidelines regarding the employment of married women in 1955:

-

1. Employment should be a necessity for the family concerned.

-

2. The family situation should always be taken into account in the employer’s decision.

-

3. Work is scheduled in such a way that sufficient time remains for family care.

-

4. No measures will be taken that infringe on the temporary nature of the employment.

-

5. Employment is provided, separated from unmarried girls and where this is not possible, in such a place that the company’s atmosphere is not damaged.Footnote 49

In addition, the board of the AKWV decided to investigate the causes of “the mass entry of married women into factories” and the “serious threats to family life” that ensued.

Importantly, these organizations’ suspicions about the “threat” of working married women were based on developments in other countries, notably the United States, Sweden, and Switzerland, where married women were employed “in great numbers” according to their sources.Footnote 50 Switzerland in particular was an important example for these organizations; after all, according to the head of the government’s industrialization policy in the 1950s, this country was seen in many ways as a role model for a successful industrialization policy.Footnote 51 While they admired the policies in these countries, Catholic employers were also concerned about the international competitiveness of Dutch industry. If other countries were to make “large-scale” use of married women, it could cause serious setbacks for Dutch industry, which made less use of this “cheap” labor force. The Dutch industry would be outcompeted. In the interests of international competition, another spiritual adviser to the AKWV, Franciscus Holthuizen, therefore urged the Catholic employers’ organizations to support all “international and national efforts to limit the labor of married women.”Footnote 52 To succeed, these organizations therefore had to build a larger coalition with other stakeholders in the Dutch industrial landscape and make an effort to propagate their policy intentions internationally in order to create a level playing field.

Curbing the Increase in Full-Time Working Women

Meanwhile, the Roman Catholic political parties, still headed by Carl Romme, reiterated their call for a ban on wage labor for married women. On this issue, the KVP was less against intervention by the central government than employers’ organizations were. In the tight labor market of the 1950s, Romme had to use different arguments to back up his position. In this period, his argument ran that the income of families with the practical opportunities for the mother to work would increase much more than the income of families where this was impossible. Hence, only couples with few children could be dual earners, thereby creating a greater inequality between small and large families.Footnote 53

In 1955, another prominent KVP politician, Father Siegfried Stokman, expressed his concerns to the Dutch parliament about the increase in the number of working married women. He feared that these women had to work out of financial necessity and that they constituted a precarious working class, thereby repeating a claim also made by the Labor Inspectorate in 1948: that “married women’s factory work” was generally a “poverty phenomenon.”Footnote 54 Stokman continued his argument with reference to the French Libre choix movement: a group that argued that married women did not enter the labor force of their own free will but were forced to work for financial reasons. If this were also the case in Dutch factories, Stokman argued, measures should be taken to protect these women from such coercion.Footnote 55 The suggestion that there was financial necessity in these cases naturally hit the breadwinner ideal; politicians such as Stokman preferred to see that women went to work voluntarily for a side income, not to support their families.

Unlike Romme, however, Stokman spoke out against government interference regarding married women choosing to work. He shared his rejection of government interference with most Catholic employers’ organizations, and supported the landmark motion raised by female MP Corry Tendeloo to abolish the dismissal provision for married female civil servants.Footnote 56 Yet his concern still focused upon women who worked full-time in industry. For him, it was a point of equal protection against work overload. The Labor Act introduced a maximum working week to protect workers from being overworked, but the fact that women with a “double day job” were not protected from working “overtime” was a thorn in his side.Footnote 57

Stimulating part-time employment was therefore his solution. Stokman even advocated full pay for part-time work. Employers, he argued, should not rely on “the consideration that this is only an extra income.”Footnote 58 He thereby took a surprisingly progressive position regarding the remuneration for part-time work. However, Stokman’s suggestion to promote part-time work was clearly aimed at limiting the time that married women worked in industry, not to activate stay-at-home mothers.

Stokman’s hope was that if his initiative were followed internationally, this could ultimately benefit the competitive position of Dutch industry, because it would create a more level playing field. That is why, in the same year, he not only brought up part-time work in the Dutch House of Representatives, but personally submitted a resolution to the conference of the International Labor Organization (ILO) to start an international investigation into the development of part-time work among married women.Footnote 59 This kicked off the international advocacy of Dutch employers’ organizations and government agencies to promote part-time work for married women internationally, a goal they would pursue well into the 1960s.

Part-Time Workers Enter the Labor Market

Stimulating part-time employment, however, was not a self-evident solution in the highly regulated Dutch labor market. Among the circles of civil servants, this kind of employment had some principled opponents. Objections were mainly raised by the inspectors of the Labor Inspectorate. After the war, information about initiatives to hire married women with a diverging work pattern reached the Labor Inspectorate, and it was forced to take a stand on this development. Its objections against part-time employment were informed by two important regulations: (1) the Labor Act of 1919 and (2) the 1945 Extraordinary Decree on Labor Relations (Buitengewoon Besluit Arbeidsverhoudingen [BBA])

The Labor Act of 1919 stipulated that women were not allowed to work in the factories between 6:00 p.m. and 7:00 a.m., unless authorized by the Labor Inspectorate.Footnote 60 Some of the recruited women, however, were appointed to work in the evening. A garment factory in the town of Budel and the chocolate factories of Droste and Ringers in Haarlem and Rotterdam, for instance, asked permission for married women to work in the evening between 6:00 and 9:00 p.m.Footnote 61 The Haarlem hosiery factory Hin—which stated that it had explicitly weighed the benefits of working from home and working in the factory in the evening—also asked the Labor Inspectorate for permission to employ women in evening shifts.Footnote 62

In 1948, the secretary general of labor made the following cautionary remark on the requests from companies to grant dispensation to employ women in the evening hours:

This phenomenon has not yet taken on major proportions, but with an accommodating attitude it cannot be ruled out that this type of employment will increase significantly. In principle, the speaker would like to take a reserved position with regard to this work. If urgent circumstances are indeed manifest, the social circumstances […] of every woman who is allowed to participate in this work must be examined, especially the care of her children.Footnote 63

In 1956, the secretary general confirmed that this permission was only given when “the care of the family” was guaranteed.Footnote 64

The female inspectors of the Labor Inspectorate played an important role in this process. In 1948, they drew up a report on the women who worked evening shifts and did packing work in the Droste and Ringers chocolate factories and in the Anjo doll factory in Zeist. They mainly inquired into childcare arrangements and the motives of these women to go to work in the evening. Their report found that most of these women had an arrangement with their husbands about childcare. The majority moreover indicated that they could not make ends meet without additional income, while a smaller group stated that they wanted extra income for large purchases, such as furniture.Footnote 65

2. Some factories opted for half-time day shifts, but the 1945 Extraordinary Decree on Labor Relations (BBA) stated that employers were not allowed to unilaterally shorten the working week to fewer than 48 hours. This issue was more complicated. In some interpretations of the BBA, employers were permitted to hire people for a shorter working week if this had been decided in mutual agreement between employer and employee.Footnote 66 In the event of a downturn in production, the inspectorate could furthermore grant permission for incidental working-hour reduction. However, if employers wanted dispensation for a specific group—such as married women—this was seen as an aspect of negotiation in the collective labor agreements.

Nonetheless, the issue of granting married women working-hour reduction was closely monitored by the Labor Inspectorate. The Philips light bulb factory in Eindhoven—which was not able to find women willing to work evening shifts—decided to employ married women in half-day shifts.Footnote 67 The Jamin sweets factory in Rotterdam also opted for this approach. From 1947 onward, married women were assigned half days, either from 8:00 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. or from 12:30 to 5:00 p.m. According to an inspector, this turned out to be a great success; many women opted to work for Jamin instead of other Rotterdam factories, precisely because of the more attractive working hours.Footnote 68

In 1947, an interesting discussion started in the offices of the Labor Inspectorate concerning the working hours in Amsterdam laundries. A group of married women were employed in this industry for 42 hours a week. The role of the inspectorate in enforcing Article 8 of the BBA was clearly not fixed at the time. Several civil servants feared that granting such “privileges” promoted married women’s willingness to look for work and wanted subsequently to intervene and enforce a 48-hour work week in these laundries. Yet the secretary general took a more pragmatic position; if there was an opportunity for them to work shorter hours—thereby mitigating the objections to the employment of married women—he considered it acceptable: “We must choose the lesser of two evils.”Footnote 69

A few years later, in 1962, when the official government employment offices started to experiment with mediating for part-time jobs, a civil servant cried out that “part-time work destroys an important social achievement: the standard employment relationship.”Footnote 70 This shows that the worries of civil servants were informed by their commitment to protecting the standard employment relationship. Attempts to reduce the working week of married women by supporting part-time employment opportunities thus had to happen in close coordination with the Labor Inspectorate, the Ministry of Social Affairs, and other parties involved in the regulation of the labor market.

“No fundamental objection”

After the shock of the rising number of full-time working married women in the mid-1950s, Catholic employers’ organizations started to gather their own data on female labor force participation. The original intent of the study was clearly to find evidence to support their specific policy position: to fully reduce women’s employment. The AKWV-affiliated Association of Catholic Apparel Manufacturers stated, for example, that their research was meant to find “all fair and possible measures […] to eliminate the unhealthy causes that might increase the married woman’s labor outside her family; it cannot be assumed that the economic advantages of the employment of married woman outweigh the disadvantages.”Footnote 71 The research was also mainly intended to find support for specific policies, such as increasing child benefits. That would be the ultimate solution for them to remove the financial necessity for women to work outside the home.

Yet results of this research took a long time, partly because the views of these employers on the direction of the research repeatedly changed. Another reason was that there was considerable opposition among individual employers against such research activities: it was “lengthy and costly work, with little results.”Footnote 72 Nonetheless, the Catholic employers’ organizations consulted other employers’ organizations about the issue, raising their concerns at meetings of the Contact Group for Increased Productivity (Contactgroep Opvoering Productiviteit [COP]), a consultative body set up on a tripartite basis to study the productivity problems in Dutch industry. The COP was partially a “propaganda vehicle” of Dutch industry, but also a consultative body on the harmful effects of Dutch productivity policy.Footnote 73 In this very context, the COP had established a special Supervisory Board on Psychological and Socio-Psychological Development. Catholic employers believed that this board was perfectly fit to conduct research into the question of working married women as a “harmful effect” of productivity policy. Moral anxieties about modernization were incorporated in the Dutch consultative framework in this way.Footnote 74

A committee headed by the director of the Labor Inspectorate P. H. Valentgoed started an investigation, supported by Marshall Aid funds, into the increase of female labor force participation. Contrary to the research of Catholic employers, however, their research statement did not explicitly mention the possibility of curbing the growing number of working women. Rather, their focus was on the question of how the “adverse consequences” of increasing female force labor participation could be offset. As was stated in a preliminary report of their research: “It is urgently desirable to investigate the consequences of married women working outside the home, as well as the possibilities of preventing or minimizing any adverse consequences.”Footnote 75 This shows how important the formulation of the questions raised by such studies was, as the questions steered the conclusions in a different direction.

The Ministry of Social Affairs had also set up a committee to look into a more focused question, namely whether legal provisions should be introduced to “protect” women working in industry. The follow-up question was, of course: “Protection against what?” This group was headed by the chairman of the workers’ protection department, A. L. Goedhart.Footnote 76 At this stage, the commission already considered asking the SER for advice on whether the government should be leading on this issue: “After all, there are such disadvantages to this work that it is necessary to consider whether the existing legal measures to protect the worker are sufficient.” At this time, however, they refrained from doing so.Footnote 77

All in all, this research, together with the other investigations, was postponed repeatedly and incomplete; the investigators were constantly confronted with different economic circumstances and changing attitudes of employers toward working women. Indeed, from 1957 onward, even Catholic employers gradually started to strike a different note on the matter of working married women. The secretary of the AKWV, H. Linnebank, noted that “the principled opponents” of working married women thus far had the support of the public opinion “but this is beginning to change.”Footnote 78

An important indication of the change in attitude was a publication by the Dutch Center for Religious Questions, which stated that there was no fundamental objection from “either Reformed, or from Roman Catholic side” to “the labor of married women outside of their family.” They still warned that “abuses can occur, which run contrary to the interests of the family,” but it was a significant statement nonetheless.Footnote 79

Another important development was the introduction of full legal capacity for married women in 1957, which removed the stipulation that a woman needed her husband’s consent before entering into an employment contract. As a result, even the manufacturers most opposed in principle to labor force participation of married women started to change their policies; the rising demand for female workers at the Tilburg Wool Manufacturers Association, for instance, prompted them to reconsider their work prohibition.Footnote 80

Meanwhile, following the suggestions made by Stokman, part-time work was widely discussed as an alternative for women who worked full-time. In 1956, the National Women’s Council complained that the opportunities for part-time work were still insufficient, and it was “of the utmost importance that employers and the government are convinced of the fairness of the married woman’s wishes to be employed, while taking into account their ‘double day-task.’”Footnote 81

In 1956, State Secretary Aat van Rhijn, one of the architects of the Dutch system of social security, furthermore stated that the government should not look at “surrogates” of motherhood, such as childcare and school meals, but believed that “our thoughts should mainly focus on the possibility of short-time work, and to create the opportunity for married women to work 24 hours a week instead of 48 hours.”Footnote 82 Hostility toward outsourcing childcare was a constant characteristic of many of the policies concerning female labor force participation in the Dutch postwar period.Footnote 83

Even in Catholic employer circles it became more and more common to speak of an “adjustment” task rather than the threat to Dutch family life. The Catholic Association of Employers in Stocking and Tricot Manufacturing, for instance, stated that it was under the impression “that the prevailing views on the labor of married woman are subject to change,” and they expected “adjustments on the part of the business community to enable married women to combine employment with the fulfilment of their domestic duties.”Footnote 84 The reports of manufacturers’ positive experiences with part-time work, such as the engineering works Stork, based in the predominantly Catholic town of Oldenzaal, further contributed to a changing attitude to part-time employment for married women.Footnote 85 These articles were actively shared in employers’ circles. In the same year, A. L. Goedhart advocated for an adaptation of working hours to working women “and not of women to working hours.”Footnote 86

Another sign that part-time work was only accepted if the breadwinner model was protected was that the growing enthusiasm for part-time work was not accompanied by the desire to completely overhaul working hours in factories. The categorical rejection of company-wide shift work testified to this. Although experiments with alternating morning and evening shifts were carried out in some places across the country, various stakeholders in the Dutch economy vehemently opposed these initiatives.Footnote 87 The main argument of the opponents of shift work, such as the Christian workers’ union CNV, was that it “disrupted orderly family life.”Footnote 88 Similarly, the Order of Company Chaplains in Breda argued that part-time work was a good solution for married women, but shift work was undesirable from the perspective of family life, especially “if the man also works shifts.”Footnote 89

In other words, part-time work was emphatically not intended as a means of redistributing household chores. Dutch employers’ organizations and unions only supported it as a supplement to the breadwinner model. A consequence of this selective support was that companies created part-time jobs mainly in the periphery of a company and not within the core business. This development determined the precarious status of part-time workers in the period that followed. They were workers on the periphery who could help with the essential business process, but the status and significance of the core labor force with a standard employment relationship remained unaffected. In this way, Dutch part-time workers, as in other countries, became part of an international precariat of underpaid marginal workers.Footnote 90

The Challenges of Working Hour Reduction

In 1959, after a brief and severe recession, the manpower shortage started to increase again in various sectors. In addition, from the late 1950s, several Dutch unions started to demand a shorter working week.Footnote 91 After all, one of the important consequences of the breadwinner model and low female labor participation was that men had to work long hours to keep Dutch productivity competitive.Footnote 92 The average working week in Dutch industry was much longer than in neighboring countries. In addition, in many sectors, especially in the metal industry, employers required many overtime hours. Furthermore, during the 1950s, 93 percent of all overtime hours were attributed to men. A large increase in overtime requests was particularly visible in the boom period between 1953 and 1957 (Figure 2).

In the context of working-hour reduction (a five-day work week), growing staff shortages, and the discrepancy between hours of operation and staff hours, low female labor participation was increasingly seen as a problem in the early 1960s. In 1960, the Netherlands Society for Industry and Trade (NMHN) explicitly recommended that a general reduction in working hours could only be realized if the loss of manpower was for compensated by female workers, that is, married women needed to work more hours.Footnote 93 This advice was a clear sign of the shift in focus from married women who worked too much to married women who were inactive on the labor market.

The downward trend in female labor force participation was by that time already pinpointed by research commissioned by the “household council,” carried out by sociologist An Schellekens-Ligthart, and in a study by the director of the Employment Office of the city of Rotterdam, B. Korstanje.Footnote 94 The explanation for the decrease in female labor force participation was mainly sought in a changing life course: girls married younger and exited the labor market at a younger age. Hence, the increase in married women in industry did not compensate for the decrease in unmarried women. In addition, a decrease in the number of women working in family-owned businesses—particularly in the agricultural sector—contributed to the overall decrease in lower female participation, according to CBS.Footnote 95

The pleas for more female labor force participation furthermore often focused on the Dutch international competitive position. An example was an extensive series of articles from G. E. Rotgans in Financieele Dagblad, in which he placed low participation in an international perspective.Footnote 96 The sociologist and “crown member” of the SER, Hilde Verwey-Jonker, agreed with this observation, stating: “There is little respect abroad for the way in which married women in the Netherlands are pampered nor for the disdain for these women as [a] labor force.”Footnote 97 Meanwhile, even Catholic employers’ associations started to look more actively into the issue of a “woman shortage” and thought about ways to increase the labor force participation of married women.

Advocating at Home

In 1960, the secretary of the AKWV explicitly acknowledged that his organization accepted “the phenomenon that more married women gradually entered industry.”Footnote 98 The organization’s new goal was to motivate married women to fill part-time jobs and to reduce their turnover. The tax system was seen as an important cause of the high turnover. Married women who earned more than 300 guilders received a hefty assessment at the end of the year. In addition, the extra costs incurred by working women, such as for domestic help, were not deductible. For many women this turned out to be a reason to stop working longer hours. This problem was also addressed in research on working married women in the Zaan district (north of Amsterdam).Footnote 99

Another effect of the tax system was the growth of temporary work agencies (TWAs). In 1962, according to officials at the National Employment Office, 13,600 women worked through a TWA in Amsterdam alone.Footnote 100 These women were mainly loaned to companies as typists without an employment contract. Because they were already insured through their spouses, it could be argued that they had no interest in paying contributions for health insurance. Tax reforms could frustrate the TWAs, which were considered “crooked” by many.

In 1960, the chairman of the textile fair, J. C. Bottenheim, stated that his organization, in cooperation with collegial organizations, wanted to “realize tax amenities for working married women.”Footnote 101 The belief that the tax system needed to be adapted was so widespread among employers’ circles that the four central organizations of employers—the Dutch Employers’ Association, the Central Social Employers’ Union, the Catholic Employers’ Union, and the Protestant-Christian Employers’ Union—decided to cooperate on the issue in 1961. In a joint communication to the minister of finance, the employers’ organizations lobbied for measures to reduce the high tax burden on married women:

While our organizations hold that married women have a primary role in the family, it has been found that there are a great number of married women whose circumstances do not preclude them from working outside the home. In addition, experience has shown that the current tax regulations seriously hinder the employment of married women. It must be noted that many are not even willing to accept a job and that there is a strong turnover among those who can be recruited, because in order to prevent or limit an assessment in the income tax, they are only willing to work a very limited number of weeks in paid employment.Footnote 102

In 1962, the tax legislation was amended: the exemption for married women was increased, and certain expenses became deductible. The breadwinner model in the tax system remained unaltered. It was still fiscally unattractive for women to work full-time, but there were fewer barriers to taking on larger part-time jobs for longer periods of time.Footnote 103

It soon became clear that the tax reforms had the desired effect. In the course of the 1960s, CBS recorded an obvious effect of the measure: The number of women in industry who worked full-time decreased, while there was an increase in small and medium-sized part-time jobs (Table 1). This proved that, with the right incentives and extrinsic rewards, most married women preferred part-time jobs over full-time jobs.

Table 1. Married women’s hours of work per week (1964 sample survey)

CBS, “Gehuwde en ongehuwde vrouwelijke arbeiders in de nijverheid”, Sociale en Economische Maandstatistiek 12, no. 3 (1964): 106.

Advocating Abroad

The commitment to part-time work that various organizations started to display, was an occasion for policy makers to look at ways in which various parts of the Dutch economy could benefit from increased participation of married women on a part-time basis. In the mid-1960s, the government therefore officially consulted the SER and the Family Council about the potential for increasing women’s labor participation. The SER had appointed Verwey-Jonker as chair of the committee to carry out the research. At this point, the question was not whether women should work part-time, but if and how they could be motivated to take a job outside the home. The information about the success of temp agencies and the effects of the tax reforms were important information for the SER committee.

Much to Verwey-Jonker’s surprise, however, the SER became internally divided on the ideological question whether increased female participation was a desirable goal in itself. According to critics within the SER, the committee placed too much emphasis on the productive/financial value of female work. The Catholic “crown member” Wim van der Grinten argued that the SER should also take “happiness” of a nation and the ideal of “healthy community life” into consideration.Footnote 104 The opposition was short-lived, thanks to the work of the SER’s “counterweight”: the Family Council. The council investigated the desirability of increased female participation and stressed the wishes of women not to participate in the labor market: “Women with family responsibilities fulfil an important function for society,” its report stated, and the government should therefore not influence “their wishes to devote themselves fully to this task.”Footnote 105

The Family Council nevertheless supported the idea of increasing the possibilities for part-time work but emphasized much more than the SER committee that part-time work should remain a voluntary choice. Policies to promote part-time work also had to go hand in hand with protecting people who voluntarily commit to the breadwinner model. This way, the SER and Family Council agreed on the endorsement of part-time work as a voluntary option for married women. In the following year, even the Dutch Catholic Trade Union Federation (Nederlands Katholiek Vakverbond [NKV]), which had always been critical of female labor market participation, published a memorandum in which they were surprisingly positive about more female participation on a part-time basis.Footnote 106

However, all these initiatives would remain meaningless if action was not taken on an international scale. If Dutch women were indeed more encouraged to work part-time, the Dutch government and employers’ organizations felt that they should also work on strengthening their international position by encouraging part-time work on a larger, international scale. This could help create a level playing field.

This resulted in an important plea from the Dutch delegation during the ILO conference in 1964. Ellen Wolf, a Dutch civil servant, lobbied here on behalf of the Dutch government to make international recommendations about part-time work for women with “family responsibilities.” Wolf had explicitly proposed an amendment to include recommendations about part-time work in the report on working women. Part-time jobs, she argued, “allowed women to fulfil their dual tasks more easily” and were also a means “of educating public opinion gradually to acceptance of the idea of women with family responsibilities working outside their homes.” Nevertheless, the amendment by the Dutch delegation was rejected by a large majority. The amendment’s opponents thought it more important to emphasize full-time jobs and felt that it was not really an international problem, because it mainly affected industrialized countries: “In the developing countries part-time employment scarcely existed and where it did it threatened to affect adversely women’s employment opportunities.”Footnote 107

The commitment of the Dutch delegation to get part-time work on the international agenda signaled that the Dutch delegation wanted to profile itself as a pioneer in the field of part-time work, precisely because the Netherlands had to catch up in the field of female labor force participation. Concerns about the international competitive position of Dutch industry in fact became increasingly serious. A critical OECD survey of the Dutch labor market from 1967 underscored this.Footnote 108 In its response to the final ILO recommendation, the Dutch government therefore expressed regret at the lack of any mention of part-time work, noting that “an incomplete working week should be considered a very appropriate option for women with family responsibilities for the Netherlands.”Footnote 109 Although the amendment was rejected, the proposal found support from other Western countries with competing industries. In this way, their proposal was not entirely ineffective: It was clear that the Dutch government wanted to strengthen its international position by promoting part-time work on a larger, international scale.

In the meantime, advocacy for part-time work by organizations in the Dutch corporate landscape continued domestically. In 1971, all employers’ organizations and trade unions represented in the Dutch consultative economy jointly spoke out in favor of more part-time employment for married women. For example, the largest employers’ organization, the Confederation of Dutch Industry and Employers (Verbond van Nederlandse Ondernemingen [VNO]) argued that recruiting married women for industry was “an absolute necessity,” while the mutual trade union federations jointly concluded that more part-time jobs should be created to enable married women to do paid work alongside their domestic duties.Footnote 110 Ultimately, this resulted in the formation of a broad coalition of employers, policy makers, and trade union members who, in the two decades after World War II, collectively found a way to boost female participation and increase productivity without undermining the highly cherished breadwinner model.

Conclusion

In the long term, the Netherlands is a good example of a country where part-time work has contributed significantly to the growing female employment rate. From a country with an exceptionally low female labor force participation rate in the 1950s, it changed into a country with one of the highest female labor force participation rates in the OECD.Footnote 111 A 2019 OECD report on the Dutch labor market noted how “high numbers of women in part-time work […] help increase the overall female labor force participation rate.”Footnote 112

Yet, in the 1950s and 1960s, different considerations than the need for more female labor force participation supported the call for part-time employment opportunities. The initial support for part-time employment was a coordinated response by employers and other consultative bodies in the Dutch economy, reacting to important developments in the Dutch and international labor markets—developments that challenged the fixed moral economy of Dutch employers, which was firmly based in the ideology of the breadwinner model. In a period of two decades, however, a policy instrument initially designed to reduce the hours women worked in industry came to be seen as a suitable way to increase the working hours of the female labor force without undermining the breadwinner model. The result was a collective emphasis on the voluntariness of part-time employment for women who chose to stay at home.

The voluntary nature of part-time work fit well with the rationale of the corporatist welfare state in Esping-Anderson’s definition. Part-time workers did not need any social protection in the breadwinner-based social insurance system and thus automatically ended up in the precarious working population. The self-evidence of the breadwinner model therefore explains why the voluntary nature of part-time work remained an important starting point in many of the discussions about working-hour reduction and the labor force participation of women in the 1970s and 1980s. The attachment to the breadwinner model created a path dependency that determined many of the policies to stimulate female labor force participation afterward—namely, work of married women in most cases had to be part-time work. The long-term success of voluntary part-time work in the Dutch economy was therefore in many ways determined by employers’ attempts to control the activities of working women the 1950s and 1960s.