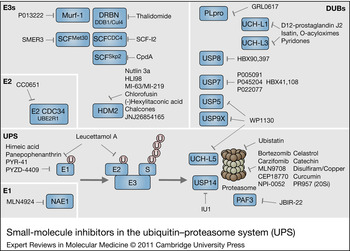

The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) controls the turnover and biological function of most proteins within the cell, and alterations in this process can contribute to cancer progression, neurodegenerative disorders and pathogenicity associated with microbes. Therefore, pharmacological targeting of the UPS can potentially provide chemotherapeutics for the treatment of tumours, neurodegenerative conditions and infectious diseases. The widespread involvement of components of the UPS in many biological processes is reflected by the fact that several hundred genes have now been associated with this pathway (Refs Reference Behrends and Harper1, Reference Clague and Urbe2). Ubiquitin is a protein with 76 amino acids that can be covalently attached to other proteins, thereby influencing their fate and function. Protein ubiquitylation has numerous physiological functions. It can act as a recognition signal for proteasomal degradation (polyubiquitylation), serve as a signalling scaffold for protein–protein interactions (Lys63-poly- or monoubiquitylation) or represent a targeting signal for the lysosomal pathway or other cellular compartments (mostly monoubiquitylation). The ability of the ubiquitylation machinery to selectively target substrates is mediated by the specificity of ubiquitin ligation (E2 and E3 enzymes) and deconjugation, promoted by deubiquitylating enzymes (DUBs). Interference with either arm of this pathway should allow highly targeted pharmacological intervention, provided that compounds with sufficient selectivity can be identified (Refs Reference Bedford3, Reference Eldridge and O'Brien4, Reference Guedat and Colland5, Reference Kirkin and Dikic6, Reference Nalepa, Rolfe and Harper7, Reference Nicholson8, Reference Sippl, Collura and Colland9) (Fig. 1). Additional opportunities are provided by the discovery of pathogen-encoded factors that evolved to target the UPS of the host cell, representing attractive targets for treatments against infectious diseases (Refs Reference Edelmann and Kessler10, Reference Isaacson and Ploegh11, Reference Lindner12). Therefore, the UPS offers a source of novel pharmacological targets as the basis for the successful development of drugs to treat human diseases. However, the complexity of the ubiquitin system causes considerable challenges for high-throughput drug discovery because of extensive structural similarities. The generation of selective inhibitors is also impeded by the large number of DUBs (Refs Reference Nijman13, Reference Reyes-Turcu, Ventii and Wilkinson14), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) and ubiquitin ligases (E3s) (Ref. Reference Pickart and Eddins15) that might have redundancies in their biological functions. All these enzymes possess affinity for ubiquitin and various ubiquitin conjugates. Therefore, their specificity is dependent on other structural subtleties and differences in protein–protein interactions unique to each enzyme species. To address this problem, an array of methodologies is used, such as the identification of ‘hits’ by high-throughput screening (HTS), the development of suitable assays for functional screening in vitro and in cells, and the use of protein structures to aid rational drug design. These approaches have already resulted in the discovery of a panel of inhibitory compounds against the proteasome, several ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and DUBs, all of which have potential for further specific drug development, as discussed here.

Figure 1. Small-molecule inhibitors in the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS). Schematic representation of components of the UPS including E1, E2–E3 ligases, DUBs and the proteasome complex (20Si: immunoproteasome). Ubiquitin is indicated as pink circle labelled U. The UPS pathway and different examples of E1, E2, E3s and DUBs are highlighted in blue boxes. Increasing numbers of small-molecule inhibitors that interfere at various steps of the UPS cascade are being discovered.

Targeting proteasome subsets for inhibition – reducing overall toxicity and overcoming drug resistance

Protein degradation by the proteasome, a multicatalytic proteinase complex, is at the centre of the UPS pathway (Fig. 1), and its pharmacological inhibition was originally considered lethal for all cell types. It was therefore rather surprising that bortezomib (Velcade) was approved as treatment for multiple myeloma in 2003 (Ref. Reference Chen16). Since then, bortezomib has also been approved for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma (Ref. Reference Kouroukis17). More recently, other derivatives have been developed that are at various stages of clinical trials, such as carfizomib (Phase III against relapsed multiple myeloma), MLN9708 (Phase I), CEP18770 (Phase I) and the natural product NPI-0052 (Phase I) (Ref. Reference Bedford3) (Fig. 1). Ubistatins were also discovered to inhibit proteasomal proteolysis by interfering with the recognition of polyubiquitin chains by the proteasome (Ref. Reference Verma18). In addition to NPI-0052, further natural products with potential anticancer properties have been characterised to interfere with proteasomal proteolysis (reviewed in Ref. Reference Schneekloth and Crews19), such as celastrol (Ref. Reference Yang20), catechin(−), the component of green tea (Ref. Reference Landis-Piwowar21), disulfiram in combination with copper (Ref. Reference Chen22), a triterpenoid inhibitor (Ref. Reference Tiedemann23), curcumin (Ref. Reference Jana24) and JBIR-22, which inhibits homodimer formation of proteasome assembly factor 3 (Ref. Reference Izumikawa25). Many of these natural products have intrinsic antitumour properties, although it is not clear whether this is solely attributable to their proteasome inhibitory capacities. For instance, statins have pleiotropic effects and are used to treat a variety of different diseases, including prevention of cardiovascular events, although it is not entirely clear whether this is due to direct or indirect interference with proteasomal proteolysis (Ref. Reference Ludwig26). As expected, proteasome inhibition causes side effects such as peripheral neuropathy, myelosuppression, nausea, hypersensibility and increased susceptibility to infection (Ref. Reference Basler27). One problem with proteasome inhibitors is the emergence of resistance; however, the combination of several proteasome inhibitors that exert complementary specificities appears to overcome the problem of resistance and might have the added benefit of enabling reduced dosing of the individual drugs (Refs Reference Mirabella28, Reference Ruschak29). An alternative way of circumventing the general toxicity of these compounds is to develop inhibitors selective for immunoproteasomes (Refs Reference Ho30, Reference Singh31). Immunoproteasomes are predominantly expressed in B-cells, T-cells, macrophages, dendritic cells and other cell types of the haematopoietic lineage, and can be induced by cell exposure to interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor -α. This leads to an exchange of the catalytic β-subunits, thereby enhancing antigen presentation and preserving cell viability during inflammation-induced oxidative stress (Refs Reference Kloetzel and Ossendorp32, Reference Seifert33). Based on the observation that the immunoproteasome promotes enhanced antigen processing and presentation, it is predicted that immunoproteasome inhibitors may have immunomodulatory effects, such as attenuating autoimmune-related pathologies. Indeed, a selective immunoproteasome inhibitor PR957 was shown to prevent experimental colitis (Ref. Reference Basler34) and interfere with arthritis in a mouse model (Ref. Reference Muchamuel35). This strategy appears to be less toxic and particularly promising for treating autoimmune disorders, and might be extended to targeting the thymoproteasome, a subform expressed in the thymus (Ref. Reference Groettrup, Kirk and Basler36).

Inhibition of DUBs as a novel approach to treat cancer, neurodegenerative diseases and viral infection

DUBs have also been molecular targets for inhibitor development in recent years (Fig. 1). Members of the DUB family known to contribute to neoplastic transformation include USP1 (Fanconi anaemia), USP2 (prostate cancer), DUB3 (breast cancer), USP4 (adenocarcinoma), USP7 (prostate cancer, non-small-cell lung adenocarcinoma), USP9X (leukaemias and myelomas) and BRCC36 (breast cancer) (Refs Reference Nijman13, Reference Reyes-Turcu, Ventii and Wilkinson14, Reference Hussain, Zhang and Galardy37, Reference Pereg38, Reference Schwickart39, Reference Song40). Mutations in the gene encoding the ubiquitin-specific protease CYLD can lead to the neoplastic condition cylindromatosis, and other DUBs are also expressed at lower levels in cancer, including A20 (B-cell and T-cell lymphomas), USP10 (carcinomas) (Ref. Reference Yuan41) and BAP1 (brain, lung and testicular cancers) (Ref. Reference Hussain, Zhang and Galardy37).

USP7 and cancer

USP7, also known as Herpes virus associated USP (HAUSP), is critical in cancer progression because of its destabilising effect on the tumour suppressor p53 (Refs Reference Nicholson8, Reference Cummins and Vogelstein42, Reference Li43). USP7 preferentially deubiquitylates the E3 ligase HDM2 and its binding partner HDMX, resulting in the destabilisation of p53 and the repression of p53 transactivation activity (Refs Reference Li43, Reference Cummins44, Reference Meulmeester45). Additional substrates of USP7 include claspin, FOXO4 and PTEN (Refs Reference Song40, Reference Faustrup46, Reference van der Horst47). Thus USP7 exerts both p53-dependent and p53-independent effects on the control of cell proliferation and apoptosis, making USP7 an attractive target for pharmaceutical intervention (Refs Reference Cheon and Baek48, Reference Nicholson and Suresh Kumar49). Recently, a high-throughput screen identified the small-molecule compound HBX 41,108 as an uncompetitive and reversible inhibitor of USP7 (Figs 1 and 2). HBX 41,108 (Fig. 2, compound 1) is a functionalised cyano-indenopyrazine derivative that inhibits several DUBs, including USP7, and stabilises p53 in a nongenotoxic manner, resulting in the induction of apoptosis (Refs Reference Guedat and Colland5, Reference Colland50). An independent screen recently identified compound P005091 and analogues such as P045204 and P022077 (Fig. 2, compound 2) as USP7 inhibitors in vitro and in living cells (Refs Reference Tian51, Reference Cao59). Proof of concept in cells was demonstrated by the stabilisation of p53 and the induction of p21 by a representative compound from the P005091 series (Ref. Reference Nicholson and Suresh Kumar49).

Figure 2. Small-molecule inhibitors against deubiquitylating enzymes. Examples of DUB inhibitors characterised in the literature targeting the USP family: HBX41,108 (1) (Ref. Reference Colland50) and P022077 (2) (Ref. Reference Tian51) specific for USP7, HBX 90,397 inhibits USP8 (3) (Ref. Reference Colland52) and IU1 (7) inhibits USP14 (Ref. Reference Lee53). Inhibitors targeting the UCH family include 15d-PGJ2 (Ref. Reference Li54) (4) and isatin O-acyl oximes (5) (Ref. Reference Liu55) specific against UCH-L3 and other isatin derivatives (6) specific against UCH-L1 (Refs Reference Liu56, Reference Koharudin57). PR-619 (6) targets a broad range of DUBs (Ref. Reference Tian51) and GRL0617 (9) inhibits SARS virus encoded papain-like protease (PLpro) (Ref. Reference Ratia58).

USP8 (UBPY) and endocytosis

As a function of its key role in the regulation of receptor endocytosis and trafficking, USP8 (UBPY) interacts with a number of clinically relevant cancer targets, including the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Ref. Reference Williams and Urbe60). Knockdown of USP8 results in the accumulation of ubiquitylated EGFR in endosomes (Ref. Reference Mizuno61). Hybrigenics reported the identification of the USP8 inhibitor HBX 90,397 (Fig. 2, compound 3). However, the clinical usefulness of USP8 inhibitors is questionable following the report that conditional knockout of USP8 in adult mice resulted in liver failure, probably as a result of pronounced decreases in receptor tyrosine kinases such as EGFR (Refs Reference Colombo62, Reference Niendorf63).

Prostaglandins as DUB inhibitors

Prostaglandins are also reported to have inhibitory activity against DUBs in cellular assays. This family of compounds form a group of lipid derivatives that serve as signalling molecules that affect diverse protein functions, depending on their localisation and physiological context. Prostaglandins have been characterised as important messengers in inflammation (Ref. Reference Scher and Pillinger64) and immune responses (Refs Reference Rocca and FitzGerald65, Reference Harris66), with emerging roles in cancer. The J-series prostaglandins are known to promote apoptosis in a p53-independent fashion (Refs Reference Clay67, Reference Mullally68). D12-prostaglandin J2 was shown to inhibit ubiquitin isopeptidase activity in cell lysates, owing to the presence of the cross-conjugated α,β-unsaturated ketones in their structure (Fig. 1). Similarly, compounds unrelated to prostaglandins, but also containing cross-conjugated α,β-unsaturated ketones and accessible β-carbons, also inhibit isopeptidase activity. By contrast, the A-series prostaglandins, which contain a single α,β-unsaturated ketone, are less efficacious as ubiquitin isopeptidase inhibitors (Refs Reference Mullally68, Reference Mullally and Fitzpatrick69). Hence, the mechanism of inhibition by J-series prostaglandins is most likely based on the nucleophilic addition of a DUB thiol to the endocyclic β-carbon of a compound and the electrophilic accessibility of prostaglandin resulting from olefin–ketone conjugation. The inhibitory effect of prostaglandins is exemplified by 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) (Fig. 2, compound 4), which inhibits the activities of UCHL-3 (Ref. Reference Li54) and UCH-L1 (Refs Reference Liu56, Reference Koharudin57) (Fig. 1). 15d-PGJ2 has a detrimental effect on UCH-L1 structure and therefore perturbs its activity, offering possibilities of interfering with progression of Parkinson disease associated with UCH-L1 mutations (Ref. Reference Koharudin57).

Punaglandins are cyclopentadienone and cyclopentenone prostaglandins chlorinated at the endocyclic α-carbon position. These compounds, originally isolated from Telesto riisei coral, exhibit anti-inflammatory and antitumour activities (Ref. Reference Baker and Scheuer70), with higher cytotoxic effects on cells than the J-series prostaglandins. Interestingly, their effect on apoptosis is independent of p53 (Ref. Reference Verbitski71). Consistent with this, punaglandins, such as punaglandin 4, are also more potent inhibitors of cellular DUB activity than the J-series prostaglandins. The proposed mechanism for this enhanced inhibitor activity is the presence of an electronegative Cl substituent at the α-position of α,β-unsaturated carbonyls that increases the reactivity towards the nucleophilic addition of the DUB catalytic cysteine thiol group. These chlorinated lipids could therefore represent a new class of cancer therapeutics (Ref. Reference Verbitski71).

Inhibitors based on other molecular scaffolds with preferential specificity towards UCHs have also been reported. For instance, Stein and colleagues have reported the discovery of isatin O-acyl oximes (Fig. 2, compounds 5 and 6) with inhibitory activity against UCH-L1 and UCH-L3 (Ref. Reference Liu55). More recently, the same group reported a second series of UCH-L1 inhibitors based on a pyridone scaffold (Ref. Reference Mermerian72). The authors speculate that these compounds might have potential in the treatment of neurodegenerative conditions.

USP14 and neurodegeneration

In HTS, the small-molecule compound IU1 was found to be a selective inhibitor of USP14. USP14 is a DUB associated with the proteasome that blocks the degradation of ubiquitylated substrates. Cellular data confirmed the hypothesis that IU1-mediated inhibition of USP14 indirectly accelerates proteasomal degradation of proteins, such as tau and ataxin-3, both of which are involved in neurodegenerative diseases (Ref. Reference Lee53). Because many neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson disease and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease are associated with the accumulation of misfolded proteins, IU1 (Fig. 2, compound 7) or other USP14-directed small-molecule inhibitors could potentially be used to eliminate these toxic proteins and improve the prognosis in neurodegenerative diseases. In support of this, USP14 has been previously linked to neurodegenerative disease, and loss of USP14 leads to an ataxic neurological phenotype in mice (Refs Reference Wilson73, Reference Anderson74).

General DUB inhibitors

WP1130 (degrasyn) is a derivative of AG490, a small-molecule compound that blocks Janus-activated kinase 2 (JAK2) activity. In cells, WP1130 treatment induces accumulation of polyubiquitylated conjugates. This phenomenon has been attributed to the inhibitory activity of WP1130 towards several DUBs, including USP9x, USP5, USP14 and UCH-L5 (Ref. Reference Kapuria75). WP1130 might be of therapeutic value, and its proapoptotic properties have been recently described (Ref. Reference Bartholomeusz76). In support of this, treatment of cells with WP1130 results in the modulation of anti- and proapoptotic proteins, such as MCL-1 and p53 (Ref. Reference Kapuria75). Further work suggests that WP1130 could be administered with bortezomib because the combination resulted in synergistic inhibition of tumour cells, regulation of apoptosis and prolonged survival of the animals (Ref. Reference Pham77).

Recently, an additional broad-specificity DUB inhibitor, PR-619 (Fig. 2, compound 8), was discovered using ubiquitin–CHOP reporter technology (Refs Reference Tian51, Reference Nicholson78). Given its broad specificity, the utility of PR-619 probably lies in its role as a tool for recovering ubiquitylated proteins from both cell-free and cellular experimental systems.

Inhibitors of viral DUBs

Viruses also encode DUBs, and these can be targeted to block viral infection. Papain-like protease (PLpro) is a DUB encoded by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (Refs Reference Lindner12, Reference Lindner79, Reference Barretto80). PLpro blocks IRF3-dependent antiviral responses, indicating its relevance to key infectious processes and viral evasion of host innate immune responses. GRL0617 is a noncovalent inhibitor of PLpro (Fig. 2, compound 9), which blocks SARS-CoV viral replication without measurable cytotoxic effects and hence is a promising antiviral drug candidate. GRL0617 induces a conformational change in PLpro, which effectively inactivates this DUB. Profiling of DUB activity in cells exposed to GRL0617 using ubiquitin-specific active-site probes demonstrated that this inhibitor is selective for PLpro, which might explain its low cytotoxicity (Ref. Reference Ratia58).

In summary, these studies illustrate the potential of many DUBs as suitable drug targets. Several challenges remain, but more recent developments in novel discovery platforms and enzyme substrates such as multi-ubiquitin chains of different type and length, CHOP reporter technology and other isopeptide-bond-based assays are now being used to identify novel DUB inhibitors with greater specificity and sensitivity, providing the framework for optimisation of more suitable drugs.

Antagonists of E3 ubiquitin ligases

E3 ubiquitin ligases represent a diverse group of proteins with significant roles in ubiquitin conjugation. First, the E3 ligases catalyse the covalent transfer of ubiquitin to a lysyl side chain of a substrate (Ref. Reference Hershko81). Second, the specificity of E3 ligases determines which substrates become ubiquitylated, based on the recognition signals on target proteins (Refs Reference Hershko and Ciechanover82, Reference Yaron83). Unsurprisingly, numerous functions in neurodegenerative disorders, autoimmune diseases, inflammation and cancer have been ascribed to E3 ligases (Refs Reference Melino84, Reference Gomez-Martin, Diaz-Zamudio and Alcocer-Varela85, Reference Nyhan, O'Sullivan and McKenna86). One of the most crucial E3 ligases in cancer cell physiology is the proto-oncogene HDM2 (or its murine homologue Mdm2), which has been reported to be amplified in many tumour cells (Ref. Reference Momand87). The best characterised substrate of HDM2 is p53, which is targeted to the proteasome by HDM2. Thus, inhibition of HDM2 leads to activation of the p53 pathway, providing an attractive therapeutic strategy for cancers that retain wild-type p53 expression. The crystal structure of HDM2 bound to p53-derived peptide reveals a deep hydrophobic cleft in HDM2 necessary for p53 binding. This feature can be exploited for anticancer treatment by a rational design of peptide- and nonpeptide-based antagonists of the HDM2–p53 interaction by targeting the HDM2 cleft.

HDM2 E3 ligase inhibitors in cancer

Nutlin-3a (Fig. 3, compound 10) belongs to a class of tetrasubstituted imidazolines and is a potent nonpeptide HDM2 antagonist. It acts as a competitive inhibitor, blocking the interaction of p53 with HDM2 (Ref. Reference Vassilev88). Consequently, Nutlin-3a stabilises p53 and its substrates p21 and Noxa, contributing to increased apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase. Its antitumour properties have been demonstrated for cancer cells expressing wild-type p53 (Refs Reference Endo97, Reference Tabe98). Nutlin-3a efficiently eliminates tumour xenografts in mice, causing no measurable abnormalities in animals (Ref. Reference Vassilev88). In other preclinical studies, the combination of Nutlin-3a and the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib induced additive cytotoxicity in malignant multiple myeloma cells. These synergistic antitumour activities might extend the clinical applications of bortezomib to neoplasias exhibiting reduced sensitivity to this proteasome inhibitor (Ref. Reference Ooi99). R7112, an analogue of Nutlin-3a, is currently in Phase I clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumours and haematological malignancies.

Figure 3. Small-molecule inhibitors against ubiquitin/Ubl-conjugating enzymes. Examples of inhibitors against E3 ligases include Nutlin-3a (10), RITA (11), MI-219 (12), JNJ-26854165 (13), chlorofusin (14) and chalcone (AM114) (15), which specifically interfere with the HDM2–p53 or HDM2–proteasome interactions (Refs Reference Vassilev88, Reference Dickens, Fitzgerald and Fischer89, Reference Duncan90, Reference Tsukamoto91, Reference De Vincenzo92, Reference Stoll93), and thalidomide (16), which inhibits CRBN (Ref. Reference Ito94). The ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 is targeted by PYR-41 (Ref. Reference Yang95) (17), and the NEDD8-activating enzyme NAE1 is inhibited by MLN4924 (18) (Ref. Reference Soucy96). All molecular targets are associated with disease pathologies, in particular cancer. See text for further details. Abbreviations: CRBN, cereblon; NEDD8, neural precursor cell expressed developmentally down-regulated 8; Ubl, ubiquitin-like protein.

The proof-of-concept data provided by the discovery of the nutlins spurred additional research in this area, including the identification of the HLI98 family of compounds (7-nitro-5-deazaflavin) and RITA (Fig. 3, compound 11) that also target the ubiquitin-ligase activity of HDM2, resulting in the activation of p53-dependent apoptosis (Refs Reference Issaeva100, Reference Yang101). In addition, the spiro-oxindoles exemplified by MI-63 and MI-219 (Fig. 3, compound 12) and the chromenotriazolopyrimidines were also reported to be effective nonpeptidomimetic small-molecule inhibitors of the HDM2–p53 interaction (Refs Reference Allen102, Reference Ding103, Reference Shangary104).

Another mode of inhibition of HDM2 is by blocking its association with the proteasome. JNJ-26854165 (Fig. 3, compound 13) is one of the first compounds found to induce p53 levels in tumour cell lines and activate p53 transcriptional activity (Ref. Reference Dickens, Fitzgerald and Fischer89). JNJ-26854165 is currently being investigated as an oral agent for the treatment of refractory solid tumours in clinical trials.

Natural products are also an important source of novel E3 ligase inhibitors. For example, 53 000 microbial extracts derived from fermented microorganisms, such as actinomycete bacteria and fungi, were screened to discover new compounds that antagonise the HDM2–p53 interaction. Among these, chlorofusin (Fig. 3, compound 14), a fungal metabolite isolated from Fusarium sp., was found to have the highest inhibitory activity towards HDM2 (Ref. Reference Duncan90). Chlorofusin has a nine-residue cyclic peptide containing an l-ornithine side chain linked to a highly functionalised tricyclic chromophore. Further studies established that neither the cyclic peptide, the chromophore of chlorofusin alone or simple derivatives thereof account for inhibition of the HDM2–p53 interaction, but that the whole structure of chlorofusin is required (Ref. Reference Clark105).

The second example of a natural product that exhibits inhibition of the p53–HDM2 interaction is the (−) enantiomer of hexylitaconic acid isolated from a culture of marine-sponge-derived fungus Arthrinium sp. (Ref. Reference Tsukamoto91). The (−) hexylitaconic acid impairs p53–HDM2 interactions in a dose-dependent manner, but its derivatives, including a monomethyl ester, a dihydro derivative and a dihydro derivative monomethyl ester, showed no inhibitory activity.

Chalcones are aromatic ketones previously characterised as potential antitumourigenic therapeutics in ovarian cancer (Ref. Reference De Vincenzo92), gastric cancer and other tumours (Ref. Reference Shibata106). Chalcone derivatives interfere with p53–HDM2 interactions by binding near the tryptophan-binding pocket of the HDM2 hydrophobic cleft (Ref. Reference Stoll93). Molecular modelling studies indicate that boronic acid binds to lysine residues Lys51 and Lys94 of HDM2 (Ref. Reference Modzelewska107). The detailed mechanism of the cytotoxic activity of chalcones remains to be determined. In some cases, the enhanced apoptosis is related to inhibition of the 20S proteasome and thus stabilisation of p53, as exemplified by boronic chalcone derivative AM114 (Fig. 3, compound 15) (Ref. Reference Achanta108). Regardless, it seems likely that chalcone-mediated inhibition of the p53–HDM2 interaction is a contributory mechanism to their reported antitumour properties (Ref. Reference Stoll93).

SCFSkp2 E3 ligase inhibitors and cancer

HDM2 is not the only ubiquitin E3 ligase that constitutes a potential therapeutic target. SCFSkp2 is an SCF (S-phase kinase-associated protein 1–cullin–F-box) ubiquitin E3 ligase containing Skp2, an F-box protein that determines substrate specificity. Upregulation of SCFSkp2 is associated with decreased p27Kip1 levels and is negatively correlated with a good prognosis in cancer (Ref. Reference Nakayama and Nakayama109); therefore, compounds directly targeting SCFSkp2 represent potential drugs for cancer therapy. Using HTS, Chen and colleagues identified compound A (CpdA) as a promising SCFSkp2 inhibitor that prevents incorporation of Skp2 F-box protein into the SCFSkp2 ligase complex. CpdA thus leads to ubiquitin-dependent accumulation of substrates for SCFSkp2 E3 ligase activity, such as p27, and consequently induces G1–S cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Notably, CpdA works synergistically with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Ref. Reference Chen110), probably by interfering with Cul1 neddylation.

Recently, two additional examples of E3 inhibitors were reported. First, using a fluorescence polarisation screen, the biplanar dicarboxylic acid compound SCF-I2 was shown to be an allosteric inhibitor of substrate recognition by the yeast F-box protein SCFCdc4. SCFCdc4 degrades many substrates, such as SIC1, in a phosphorylation-dependent manner, and the SCF-I2 inhibitor perturbs the phosphodegron binding pocket of SCFCdc4 (Ref. Reference Orlicky111). A second group used a yeast-based chemical genetics screen to identify modulators of SCFMet30 activity (Ref. Reference Aghajan112). Biochemical studies confirmed that SMER3 specifically inhibits SCFMet30-dependent ubiquitylation of the transcription factor Met4 by reducing the binding of Met30 to Skp1, which is probably due to its direct binding to Met30.

CRBN E3 ligase targeted by the teratogenic agent thalidomide

Cereblon (CRBN), damaged DNA-binding protein 1 (DDB1) and Cul4A form an E3 ligase complex that is important for embryonic development. This complex is targeted by thalidomide (Fig. 3, compound 16), a clinically approved drug for the treatment of multiple myeloma, leprosy and inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn disease) (Ref. Reference Bosch113). One of the enantiomers of thalidomide was found to have teratogenic side effects. Binding of thalidomide to the CRBN complex and inhibition of CRBN E3 ligase activity appear to be the underlying molecular mechanisms for thalidomide-induced teratogenicity by the perturbation of embryonic development (Ref. Reference Ito94).

MuRF1 E3 ligase inhibition and muscular atrophy

MuRF1 is a key effector enzyme of muscular atrophy, an area of unmet medical need for several different pathologies (Ref. Reference Bodine114). Using an ELISA-based HTS platform, Progenra identified a novel modulator of the E3 ubiquitin ligase, P013222, which inhibited MuRF1 autoubiquitylation and myosin heavy-chain ubiquitylation and protected myotubes from dexamethasone-induced muscle wasting (Ref. Reference Eddins115).

As outlined above, most of the identified E3 ligase inhibitors are directed towards protein–protein interactions, and their ‘druggability’ is therefore challenging. The complexity of this enzyme family, the lack of details on their precise molecular mechanism and the fact that most E3s rely on protein–protein interactions to mediate their activity makes the design of E3 ligase inhibitors difficult (Ref. Reference Eldridge and O'Brien4), but potentially offers the framework for translational applications by interfering with many different biological processes in a highly specific manner. Recent reports of the identification of specific SCF inhibitors increase our confidence that it will be possible to develop inhibitors of this emerging class of important drug targets.

Inhibition of ubiquitin-activating enzymes

Ubiquitin conjugation requires initial activation of ubiquitin by E1 enzyme, which adenylates the C-terminal carboxyl group of ubiquitin, forming a high-energy ubiquitin adenylate intermediate, followed by the formation of a thiol ester between the carboxyl group of Gly76 of ubiquitin and a thiol group of E1. This series of reactions activates the C-terminus of ubiquitin for a subsequent nucleophilic attack (Ref. Reference Ciechanover116). Blocking this reaction could therefore be used to inhibit ubiquitin conjugation. In vitro studies suggest that knockdown of E1 ligase results in lower levels of protein ubiquitylation and eventually induces cell death in malignant cells (Ref. Reference Xu117). To identify novel E1 inhibitors, Yang and colleagues screened a library of small compounds and identified 4[4-(5-nitro-furan-2-ylmethylene)-3,5-dioxo-pyrazolidin-1-yl]-benzoic acid ethyl ester (PYR-41) as the first cell-permeable E1 inhibitor. PYR-41 efficiently reduces bulk protein ubiquitylation and sumoylation, and prevents degradation of p53, contributing to enhanced apoptosis. PYR-41 also attenuates cytokine-mediated nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation by regulating proteasomal degradation of IκBα, an inhibitory subunit of NF-κB. Functionally, PYR-41 probably binds irreversibly to the active-site cysteine in E1 ligase, therefore preventing ubiquitin transfer (Ref. Reference Yang95). However, this compound also targets several DUBs, including USP5, and crosslinks to kinases and has antitumour activity in animals (Ref. Reference Kapuria118). PYZD-4409 (Fig. 3, compound 17), another small-molecule inhibitor, has been shown to interfere with the activity of E1 ligase, preferentially inducing tumour cell death in primary acute myeloid leukaemia cells. The effects of PYZD-4409 have also been studied in a mouse model of leukaemia, where it reduced tumour weight and volume. This study underlines the importance of E1 as a potential drug target in leukaemia and possibly other cancers, especially in cases where neoplastic cells are resistant to treatment with proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib (Ref. Reference Xu117). Furthermore, two natural products have been identified to inhibit E1, panepophenanthrin isolated from the mushroom Panus rudis (Refs Reference Sekizawa119, Reference Matsuzawa120) and himeic acid A derived from the fungus Aspergillus sp. (Ref. Reference Tsukamoto121), both of which inhibit the E1-catalysed ubiquitin activation in vitro, but with unknown mechanisms.

Recently, small-molecule inhibitors of E2 enzymes were also discovered. Leucettamol A, a compound isolated from a marine sponge Leucetta aff. Microrhaphis, was identified as a novel inhibitor of the Ubc13–Uev1A interaction, thereby blocking the formation of the E1–E2 complex (Ref. Reference Tsukamoto122). Also, an allosteric inhibitor of the human Cdc34 E2 ligase, CC0651, was found through a small-molecule screen for inhibitors of SCFSkp2-dependent ubiquitylation of p27Kip1, and was shown to interfere with the proliferation of human cancer cell lines (Ref. Reference Ceccarelli123).

Generally, when targeting E1–E2 conjugating enzymes, several pathways that are dependent on ubiquitylation, such as DNA repair or endocytosis, are inhibited at the same time, potentially contributing to increased nonspecific cytotoxicity. Therefore, from the therapeutic standpoint, the use of ubiquitin E1 (or E2)-specific inhibitors is currently awaiting additional preclinical validation before advancing to clinical studies.

Targeted inhibition of NEDD8-activating enzymes

Neural precursor cell-expressed developmentally downregulated-8 (NEDD8) is a ubiquitin-like protein with the highest homology to ubiquitin. Its conjugation to substrates (neddylation) requires activation by the E1 APPBP1-UBA3 and transfer by the E2 UBC12 (Ref. Reference Xirodimas124). NEDD8 primarily functions in the regulation of E3 ubiquitin ligases, modifying most members of the cullin family. Cullins are scaffold components of the SCF E3 ubiquitin ligases that control the proteasomal degradation of proteins involved in the cell cycle, transcriptional regulation or signal transduction (Refs Reference Xirodimas124, Reference Herrmann, Lerman and Lerman125). Neddylation of cullins results in increased ubiquitylation of the SCF substrate proteins and their subsequent proteasomal degradation. SCF E3 ligases promote the ubiquitylation of proteins involved in inflammation and tumourigenesis (Ref. Reference Pan126), such as HIF-α and IκBα (Refs Reference Clifford127, Reference Soucy96); therefore, specific inhibition of NEDD8-activating enzymes (E1) and other components of the neddylation pathway represents an alternative approach to targeting the UPS for cancer treatment. MLN4924 (Fig. 3, compound 18) is a small-molecule inhibitor of the NEDD8-activating enzyme and is presently being evaluated in Phase I clinical trials. MLN4924 increases the apoptosis of several tumour cell lines and murine tumour xenografts and is considered a promising drug candidate for myeloid leukaemia (Refs Reference Soucy96, Reference Soucy, Smith and Rolfe128, Reference Swords129). In contrast to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, MLN4924 is more specific because it does not inhibit bulk proteasomal degradation (Ref. Reference Soucy96). The functional mechanism of MLN4924 involves formation of the MLN4924–NEDD8 covalent adduct, which is similar to the first intermediate of the reaction catalysed by the NEDD8-activating enzyme, thus efficiently inhibiting the NEDD8 E1 enzyme (Ref. Reference Brownell130).

Given that SCF E3 ligases represent several hundred of all known E3 ubiquitin ligases, there is concern that inhibition of ~300 E3 ligases might lead to serious side effects in a clinical setting. However, the impact of side effects must be taken in the context of proteasome inhibitors, which have been shown to exhibit acceptable clinical profiles for the treatment of cancer, yet modulate the stability of many more proteins (relative to SCF E3s). Ultimately, the evaluation of MLN4924 and any successor compounds in a clinical setting will determine whether this strategy is a therapeutically acceptable approach.

Conclusions and perspectives

The ubiquitin system or ‘ubiquitome’ has been compared with the well-characterised ‘kinome’ and has spurred an entire array of novel inhibitors against molecular targets that manipulate ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like molecules. Similarly to the kinase field, functional redundancy, the structural similarities of active sites (DUBs) and the diversity of protein–protein interaction domains (conjugating enzymes) render the discovery of specific inhibitors challenging. Several novel compounds are promising results in clinical trials, such as the proteasome inhibitors carfizomib (Phase III), MLN2238 (Phase I) and NPI-0052 (Phase I) or the NAE inhibitor MLN4924 (Phase I against AML and solid tumours). Thalidomide, which has been in clinical use for many years, has been recently identified as an E3 ligase inhibitor. Also, several E1 and E3 ligase inhibitors such as PYR-41, Nutlin-3a, Compound A, P013222 and SCF-I2 have proved successful in the preclinical stage. Generally, it remains to be determined whether small molecules are required to specifically target only one molecule to be clinically useful or whether, in a manner similar to medically relevant kinase inhibitors, molecules with broader specificities against subfamilies of enzymes might exhibit clinical efficacy. Clearly, the emergence of new inhibitors directed against UPS components supplements the activities of kinase inhibitors, cytotoxic agents and other compounds, and it is predicted that ultimately the combinatorial use of these drugs holds the greatest promise for future therapies against cancer, neurodegenerative disorders and infectious disease. These disease pathologies are highly complex, and substantial differences can occur between individuals. A broadened arsenal of small-molecule compounds, including drugs targeting components of the UPS, might provide the framework for individualised drug regimens as part of a trend towards personalised medicine.

Outstanding research questions

• Generate further understanding of the precise role of E1/E2/E3 ligases and DUBs and other components in the UPS in disease processes, to establish correlations between their dysfunction and properties of disease pathology.

• Develop promising lead compounds into more effective inhibitors with greater potency.

• Whereas many small-molecule compounds show antiproliferative activities in tumour cell lines, it is less clear how this can be translated into inhibiting tumour growth in vivo without affecting normal cells. Distinguishing between these two scenarios should drive the selection and development of more effective compounds in the future.

• Is it really necessary to chemically target one enzyme for optimal interference with disease progression? Many diseases, in particular cancer, exert aberrations in several biochemical pathways. The discovery and pharmacological targeting of all abnormally functioning networks will be necessary for better treatments in the future.

Acknowledgements

M.J.E. is supported by a USDA NIFA grant (Nr. 2009-34609-20222). B.N. is supported by grants DK07139 from NIDDK/NIH and CA115205 from NCI/NIH to Progenra Inc. B.M.K. is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, UK and by an Action Medical Research Grant (Charity Nr. 208701 and SC039284). We thank members of the Kessler group for helpful discussions and also the peer reviewers for useful comments on the manuscript.