A glass of water that stands in front of someone speaking is a sign that marks this person as a lecturer, but as an object it also has the prosaic function of quenching thirst. With this example, Roland Barthes describes how objects can function as signs.Footnote 1 Stern water glasses are naturally of little interest for this chapter; or, as a Greek epigrammatist says: ‘our mixing bowl does not welcome water-drinkers’ (AP 11.20 = Antipater of Thessalonica 20 GP). Yet, Barthes’ thoughts on objects as signs are worth pursuing: how do we read objects and when does an object become a sign? And, more specifically, how is the carpe diem motif expressed through objects and signs? So perhaps it is possible to stay with Barthes’ sober image for a little longer before it is time for a stronger mixture. Barthes assigns two different qualities to objects. The first is their function as an object: quenching thirst, in the case of the water glass. The second quality is their function as sign: the sign of the lecturer, in the case of the water glass. In his discussion, Barthes takes the first quality for granted and is primarily interested in this second quality, the object as a sign. The drawback of this approach is that the materiality of the sign goes unappreciated. Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht sees this clearly: ‘the purely material signifier ceases to be an object of attention as soon as its underlying meaning has been identified’.Footnote 2 In this chapter, my interest lies in both qualities of objects, that is, their materiality as well as their function as signs. I will also analyse how these two qualities interact with each other.

Too theoretical and sober? Time to serve some stronger stuff, then: cups of wine are signs that signify the banquet in the Greco-Roman world. But what difference does it make if the sign that signifies the banquet is the cup itself, or a song that mentions a cup, or an image that shows a cup, or a book that writes about a cup? In tackling such questions, I will combine two different views. On the one hand, I am interested in the sign and in the curious ways in which cups can oscillate between being objects, texts, and images. We thus hear of someone who is proud to have a famous cup from literature in his collection of physical drinking vessels. Or we read of descriptions of cups so vivid that we seem to see the object cup in front of our eyes. Throughout different media, the cup signifies the banquet. On the other hand, I wish to stress the materiality of the cup and what makes the cup an object. Naturally, presence is an important aspect to this: holding a cup in one’s hand, touching it, smelling the wine, tasting the wine – this is different from reading about a cup. This gap is where the carpe diem poem is situated as it attempts to evoke the presence of the cup. I have already looked at such a feeling of loss and the attempt to compensate for it in other chapters. In the present chapter, I will show how carpe diem poems evoke the presence of objects and how this is crucial for evoking present enjoyment.

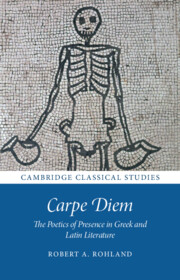

The chapter falls into three sections. Cups have already made their presence felt in the preceding two paragraphs, and cups and the banquet will indeed be the focus of the first section. The second section will turn to gems and luxury. The third section will consider a combination of two objects: dining halls and tombs. In terms of texts, most Greek epigrams discussed here are taken from the Garland of Philip, while the Latin material comes from Petronius, Pliny, and Martial. The focus of my discussion will thus lie on material between 100 ʙᴄ and ᴀᴅ 100. From this period a high number of Greek and Latin epitaphs survive that feature the carpe diem motif.Footnote 3 It is also in particular in this period that artworks express the carpe diem motif through the prominent depiction of skulls and skeletons, as Katherine Dunbabin has shown in a seminal study.Footnote 4 Finally, we know of some elaborate parties in this period which are wholly centred on carpe diem. For instance, we are told that Emperor Domitian hosted a meal in which every single detail could remind his guests of death and funerals: place cards in the form of gravestones bearing the guests’ names, black dishes, beautiful slave boys who looked like phantoms, and many more such details. After the dinner, the guests received dishes and other items, perhaps as a form of memento. Domitian’s meal juxtaposes death and dining, which is often done as a reminder to enjoy life. Yet, Domitian brings the theme to its limits, and his guests have to envisage their death as a very real possibility, as Catharine Edwards has shown.Footnote 5 Trimalchio’s Cena from Petronius’ Satyrica is another banquet from this time that is hardly less elaborate in its staging of the carpe diem motif, and I will consider aspects of this banquet later in this chapter. What to make of this seeming prevalence of carpe diem in this period? It, arguably, would go too far if one were to conclude that people’s minds turned to death in the unstable period following the fall of the Republic.Footnote 6 Rather, the first centuries ʙᴄ and ᴀᴅ seem to show a particular interest in elaborate, luxurious ways of staging carpe diem. We know of numerous ornate objects which express the motif, such as cups, tables, and figurines.Footnote 7

As this chapter analyses the relation between objects and texts, it is only natural that epigrams, which are literally texts ‘written onto’ objects, become the focus of attention. The relation between objects, art, and epigram has long been recognised as significant, and ekphrasis has consequently been a major theme in discussions of epigrams.Footnote 8 More recently, this field of study has received stimuli from three sides. First, a growing interest in ‘material culture’ throughout the humanities made scholars consider more carefully the seemingly mundane objects that are thematised in epigrams. Second, both art historians and literary scholars found interest in forms of collections, whether they be collections of artefacts or of literature. Third, an important papyrus find opened up new avenues to understanding the relations between epigrams and objects.Footnote 9 Nonetheless, many texts discussed in the present chapter have received little attention, and scholarship is, for example, virtually silent on the epigrams of authors such as Apollonides, Zonas, or Marcus Argentarius that are discussed here. Careful attention to these texts can elucidate how one can read carpe diem through objects.Footnote 10

The time investigated here, the Roman Republic and early Empire, means that Greek and Roman evidence must be treated collectively. One Greek writer evidently describes a Roman gem, which he might have encountered while he mixed with the Augustan court. Another Greek epigrammatist describes a Roman conuiuium rather than a Greek symposium in one of his poems.Footnote 11 A Greek cutter of a gem discussed here may have worked in Rome. In short, any division of this chapter’s material along the lines Greek or Roman would be artificial and curtail the exploration of Greco-Roman objects and texts.

4.1 Cups

Cups are fundamental to the symposium. In the ancient world, Athenaeus and Macrobius recognised their significance and wrote learned accounts on various types of cups and their appearances in literature (Ath. Book 11, Macr. 5.21). Renaud Gagné has recently joined the party of these learned banqueters, and he has discussed in some detail the cup in Greek literature. For Gagné the cup is the ‘degree-zero symbol of the symposium’.Footnote 12 With this term from Roland Barthes, Gagné underlines the strong semantic role of the cup: any cup anywhere can point to the symposium.Footnote 13 The symposium is the natural space for enjoyment, the space that carpe diem poems evoke. In sympotic epigrams, published in books and thus separated from the sympotic space, cups are an important sign that can conjure up the symposium. Yet, already early lyric conjured up the presence of cups. A common formula on sixth-century-ʙᴄ cups is the following call to drinks: χαῖρε καὶ πίει τε̄́νδε (‘be happy [or: greetings] and drink this’).Footnote 14 It has been frequently noted that this expression finds a virtually verbatim parallel in one of Alcaeus’ sympotic songs (fr. 401a and b):Footnote 15 (a) χαῖρε καὶ πῶ τάνδε (b) δεῦρο σύμπωθι ((a) ‘be happy [or: greetings] and drink this’ (b) ‘come here and join in the drinking’). Inscriptions as well as Alcaeus’ poem refer to a cup with a deictic pronoun: the cup is present. It is tempting to see in Alcaeus’ song the song of a momentary now at the symposium: while Alcaeus tells his audience to drink this cup, they may indeed hold this cup in their hand and look at letters which mirror Alcaeus’ song.Footnote 16 This, however, is an idealised image. Although cups which mirrored Alcaeus’ song in inscriptions might have been common, not every single symposiast would have held such a cup with exactly this writing in his hand for every reperformance to come. Alcaeus already produces effects of presence rather than simply presence.Footnote 17 Epigrammatists would follow this technique.

As we turn our attention to the first centuries ʙᴄ and ᴀᴅ, we will do well to begin our discussion with actual cups. Among the most spectacular cups from the ancient world are two that are part of the Boscoreale treasure (Figures 4.1–4.2), unearthed in the bay of Naples in 1895 and now in the Louvre (Louvre Bj 1923, 1924).Footnote 18 Dated to the Augustan-Tiberian era, the two silver cups urge viewers to carpe diem qua the depiction of skeletons. Garlands that are embossed below the rims of the cup set a sympotic scene throughout, and several skeletons engage in sympotic activity: on Cup A, one skeleton is playing a lyre; another puts a garland on his head; yet another looks at a skull. Other activities on the two cups are not sympotic, though they also stress the carpe diem message, and we will encounter them again in this chapter. Thus, one skeleton holds a butterfly in his hand, which is labelled ψυχίον (‘little soul’), and a purse labelled φθόνοι (‘envy’) in the other hand. Yet another skeleton pours a libation over an unburied mangled skeleton that lies on the ground on Cup B. Beside the skeletons that are anonymous revellers, other skeletons are identified by inscriptions as philosophers and poets. This includes, on Cup A, Sophocles, Moschion, Zeno, and Epicurus, and, on Cup B, Menander, Archilochus, and Monimus. The cups combine several concepts of ‘the thought and art of Graeco-Roman society of the first centuries B.C. to A.D.’, as Katherine Dunbabin has shown,Footnote 19 for in this period skeletons and skulls widely express the carpe diem motif in the form of figurines and on cups, gems, mosaics, tombs, and earthenware. The depiction of dramatists as skeletons reflects the idea of life as a stage, and the skeleton-philosophers point to sentiments about the universality of death, which even philosophers, for all their wisdom, cannot avoid.

Figure 4.1(a, b, c) Silver cup with skeletons (Cup A)

Figure 4.2(a, b, c) Silver cup with skeletons (Cup B)

One skeleton whose role has not been sufficiently explained is the one of Archilochus playing the lyre on Cup B (Figure 4.2(b)). Of course, this could just be an extension of the theme ‘everyone dies, even famous philosophers and poets’, as Dunbabin suggests.Footnote 20 But there may be more to it; as the cups are sympotic objects, which depict sympotic scenes, Archilochus might have been shown here as a sympotic poet. As a poet who famously drinks reclining on his spear (fr. 2) and who is characterised as ‘wine-stricken’ by Callimachus, he is an appropriate subject for a cup (fr. 544 Pfeiffer: μεθυπλῆγος). Moreover, some fragments of Archilochus have been interpreted as carpe diem pieces.Footnote 21 On Cup A, there is a corresponding skeleton playing a lyre (Figure 4.1(b)). While it is anonymous, Dunbabin has convincingly proposed that the parallel between the two cups suggests that this was also meant to be a well-known poet.Footnote 22 Above this skeleton’s lyre is written τέρπε ζῶν σεα[υ]τόν (‘while you are alive, enjoy yourself’). The position of these words, placed directly over the lyre, suggests that they represent a song that arises from the instrument.Footnote 23 Perhaps this line of song would have indicated the identity of the poet to an ancient viewer. At least given the attention to detail that the cups display, this seems a more likely deduction than to simply assume with Dunbabin that the artist had forgotten to include the poet’s name.Footnote 24

The Boscoreale cups include more phrases which represent sympotic song. Thus, on Cup B, the following words are placed above two smaller skeletons representing slaves, of which one plays pipes and the other one a lyre (visible on Figures 4.2(a) and 4.2(b)): εὐφραίνου ὅν ζῆς χρόνον (‘enjoy the time that you are alive’).Footnote 25 Finally, Cup A shows a third exhortation: ζῶν μετάλαβε· τὸ γὰρ αὔριον ἄδηλον ἐστι (‘take a share in life; for tomorrow is uncertain’). This sentence is written below a Hamlet-like skeleton who looks at a skull (Figure 4.1(a)). Indeed, at first one may entertain the possibility that these sentences should be attributed to our Hamlet skeleton. The exhortation, however, makes little sense when spoken to a skull; it should be addressed to the living (or the quasi-living skeletons). Yet, it is equally difficult to imagine that the skull voices this sentence. It is thus most natural to assume that this exhortation, too, represents song and should be attributed to the small skeleton clapping his hands below the letters. The parallel between the two cups supports this interpretation: Cup B shows a song in corresponding position above two small skeletons. Consistency also seems to demand this conclusion: all three exhortations on the cups are represented as song.

That the Boscoreale cups are signs of the banquet is clear enough, but the complexity in their use of motifs and media is striking, and perhaps most so in their evocation of song. In addition to the inscribed songs, the structure of the cups also helps to evoke music: the garlands at the upper rim and the small dancing skeletons at the lower end of the cup give a rhythmic sympotic feeling to the whole scene. As the cups evoke music, they can reinforce the musical enjoyment at the banquet and truly create present enjoyment: touching the cups, feeling the skeletons and the silver material, and tasting wine from them creates enjoyment. And yet, these cups also express a sentiment of loss and nostalgia for a lost ideal of early lyric song: Archilochus plays the lyre and urges banqueters to live it up, but Archilochus has already been dead for centuries and he as well as his fellow banqueters are skeletons. Song is not so present after all. The cups thus raise a key question that will concern us in this chapter: how do we read objects instead of listen to songs, in the context of carpe diem?Footnote 26

As we turn to texts, let us begin with an epigram that stresses the materiality of the cup – though clay instead of the silver of the Boscoreale cups. The epigram, included in the Garland of Philip, is attributed to Zonas, an epigrammatist of whom little is known unless he is to be identified with Diodorus Zonas, an influential orator around the time of the Mithridatic Wars in the first century ʙᴄ.Footnote 27 In the epigram, a speaker talks of a clay cup (AP 11.43 = Zonas 9 GP):

Give me the sweet cup made from earthenware, earth from where I came and under which I will lie again when I am dead.

The epigram seems to have eluded critical attention. It falls into two parts. In the hexameter, a symposiast asks someone for a sweet cup. This is the sympotic gesture par excellence, the call for drinks.Footnote 28 The command in this line thus evokes a scene at the banquet, and a reader places both the speaker and his addressee at the symposium. The hexameter, then, lets us listen to the chatter of sympotic dialogue, and we can find a parallel for such a piece of casual dialogue in the words of a thirsty slave in comedy (Ar. Eq. 120, and similar again in 123): δός μοι, δὸς τὸ ποτήριον ταχύ (‘give me, quickly give me the cup’).Footnote 29

The pentameter evokes a different image. Two relative clauses offer more information on the cup’s material, earthenware. The speaker says that like the cup he comes from the earth and will lie again under the earth when he is dead.Footnote 30 The language in the pentameter is evocative of epitaphs. In particular the first-person verb κείσομαι points to funerary epigrams, in which κεῖμαι is an extremely common, formulaic expression.Footnote 31 The epitaphic heritage of the genre is inscribed into the DNA of the Zonas’ epigram. Exhortation to present enjoyment and insight into human mortality are expressed through a line of sympotic dialogue that clashes with a line evocative of funerary epigram.Footnote 32 The implicit lesson of the epigram is carpe diem – drink from earthenware now before the same material will surround you in death. The sweet cup acts as a sign for the pleasures of the symposium, but the cup shares its material with the earth that will entomb us. Within a single elegiac couplet, we listen to pleasant sympotic chatter and read of death. The poem evokes both the tactile presence of an earthenware cup at the banquet and the letters on an epitaph; in doing so, it oscillates between presence and meaning. It is precisely in this interaction of materiality and reading, of object and sign, of sympotic dialogue and funerary epigram, where we find the carpe diem motif. As we seem to touch the cup’s earthenware material, taste its sweetness, and as we interpret the cup as a sympotic sign and discern the letters of the epigram evocative of inscriptions, we read carpe diem.

An epigram of Apollonides raises further questions on how one can read cups. Apollonides was a Greek poet who wrote in the first century ᴀᴅ in the Roman Empire and may have lived in Asia, as two of his epigrams possibly mention pro-consuls of Asia.Footnote 33 In the following epigram, Apollonides describes how someone is asleep at the symposium and his cup calls him back to action (AP 11.25 = 27 GP):Footnote 34

You are sleeping, my friend, but the cup itself is shouting for you: wake up and don’t enjoy practising for death. Don’t be sparing, Diodorus, but rather slip greedily into Bacchus’ wine and drink it neat until the legs give way. There will be a time – a long, long time – when we will not be drinking. But come get up. Sober old age is already touching our temples.

Although this poem is praised by Gow and Page as ‘perhaps the best’Footnote 35 of Apollonides’ epigrams, it has like many of the epigrams from the Garland of Philip received no critical attention. This is a pity, for the poem elegantly combines features of inscribed epigram and Hellenistic literature with the fashion of the early Empire.

The first line sets the scene: someone addressed in the second person is asleep at the symposium and his cup ‘is shouting’ (βοᾷ) at him. The following line is set in quotation marks by Gow and Page as the content of the cup’s speech:Footnote 36 ἔγρεο, μὴ τέρπου μοιριδίῃ μελέτῃ (‘wake up and don’t enjoy practising for death’). The cup admonishes the sleepy symposiast to wake up and not to enjoy his sleep, here wittily called a ‘practice for death’ (μοιριδίῃ μελέτῃ). It is interesting if the admonition comes from the cup. To be sure, we can also find a talkative wine vessel in a charming epigram by Apollonides’ contemporary Marcus Argentarius, who calls a flagon (λάγυνος) ‘sweet-talking, soft laughing, large lipped, long-throated’, clearly punning on the shape of the vessel and its function at the symposium (AP 9.229 = 24 GP). Furthermore, a cup that was passed around at a symposium and indicated who was singing was itself called ᾠδός (‘singer’).Footnote 37 Thus, wine-vessels as symbols of the symposium can act like symposiasts, chatting and singing. The case of the cup in Apollonides’ epigram, however, is arguably different. For the shout of the cup might be best understood as a reference to an inscription on a cup, as the epigram plays with the heritage of the epigrammatic genre in inscriptions. Words of verbal action are regularly used for inscriptions on epigrams and blur the lines between speaking and writing,Footnote 38 but perhaps more specifically relevant is a cup in a satyr play which is said to ‘call’ (καλεῖ) someone ‘by showing its inscription’.Footnote 39 This neatly shows how an inscription on a cup can simultaneously function as an inscription and as a verbal action. Irmgard Männlein-Robert says about epigrams of similar form that the voice of the epigram only becomes articulate once the reader lends his own voice to the epigram as he reads the text aloud.Footnote 40 Indeed, in our present case we can see such a reception in action, as the speaker of the epigram reads out the inscription of the cup to the sleeping Diodorus, thus giving a voice to the epigram.

If the ‘shout’ of the cup is understood as an inscription on a cup, the question arises whether this speech or inscription is really just limited to one line, as most editions mark it. The exhortation in the following line suggests otherwise: μὴ φείσῃ, Διόδωρε (‘don’t be sparing, Diodorus’). This negated imperative closely follows μὴ τέρπου (‘don’t enjoy’), and it is most natural to assume that both imperatives are said by the same speaker, the cup. Furthermore, this exhortation displays the most typical features of inscriptions on cups: an indication of the owner and an exhortation to drink. I thus suggest that lines 2–4 should be placed into quotation marks as being spoken by the cup.Footnote 41 The device of the speaking cup is noteworthy, and the verb βοᾷ (‘the cup is shouting to you’), which introduces the speech of the cup, encapsulates issues of presence and absence. The loudly shouted imperatives evoke presence and the exuberant space of the banquet. And yet, this shout turns out to be an inscription on a cup, something read rather than sung.

Apollonides’ epigram stages the act of reading carpe diem. The epigram displays self-consciousness about its status as a text and about the role of the reader. It may therefore be unsurprising that the epigram also includes a sophisticated philological note. One of what I take to be the cup’s exhortations is the imperative ζωροπότει (‘drink neat wine!’). Gow and Page do not comment on this word, though this rare compound-word might be the most marked one in the epigram. In Chapter 3 on Horace’s choice of words, it was already possible to take a sip from this neat wine of words; now it is time to down it properly. The verb ζωροποτέω derives from the adjective ζωρός, a Homeric hapax legomenon, which appears at Iliad 9.203. There, Odysseus, Ajax, and Phoenix visit Achilles in his tent, who tells Patroclus to bring a larger mixing bowl and to mix something ζωρότερον. The meaning of this word was subject to much debate in the ancient world: some considered it to refer to old wine, others took it to mean ‘quicker’, yet others thought it to signify ‘hot’ or ‘boiling’ wine, but most accepted the meaning ‘neat’ or ‘unmixed’. Such philological debates were themselves regularly set at symposia and suited the self-referential sympotic space: at the literary symposia of Plutarch and Athenaeus the question about the meaning of ζωρότερον is a sympotic question in more than one sense (Plu. Moralia 677c–678b, Ath. 10.423d–424a).Footnote 42

It is in particular Callimachus’ use of ζωροποτέω in the Aetia, quoted in Chapter 3, which strongly influenced later literature (fr. 178.12 Harder, page 136 in this book).Footnote 43 Indeed, Paul Maas had already suggested that Apollonides took ζωροποτεῖν from Callimachus.Footnote 44 Callimachus notably rejects the fashion of drinking neat wine, but many poets would write polemic allusions to this passage. This is, in particular, the case with carpe diem poems, as we have seen in Horace’s case (C. 1.36.13–14, pages 135–8 in Chapter 3). In epigrams it becomes difficult to tell if poets are more intoxicated from the neat wine they describe or from the philological fascination that this term entails. Thus, Hedylus begins an epigram with the resounding noun ζωροπόται (‘drinkers of neat wine’), which helps him to characterise his poetic programme in contrast to Callimachus, as Sens has analysed in detail (4 HE apud Ath. 11.497d).Footnote 45 Even much later, in sixth-century-ad Byzantium, Callimachus’ passage still invited allusive games among epigrammatists. Thus, Macedonius begins a poem with the hapax legomenon χανδοπόται (AP 11.59), perhaps modelled on Hedylus’ incipit, but almost certainly alluding to Callimachus’ striking expression χανδὸν ἄμυστιν ζωροποτεῖν (‘drinking neat wine with the mouth wide open in large draughts’).Footnote 46 Terms around ζωρο- would also act as a tool for cross-referencing and editing when Meleager compiled his collection of epigrams. For as he found ζωρός in a carpe diem poem of Asclepiades (AP 12.50 = 16 HE), Meleager placed a poem of his own before this, which he introduced with the verb ζωροπότει (AP 12.49 = 113 HE).Footnote 47

Cross-referencing is perhaps not something that many people associate with hard drinking. Yet this peculiar double nature of the word ζωρός goes some way towards explaining the dynamics of reading carpe diem. The one side in Apollonides’ epigram is the emphatic imperative ζωροπότει; this is much stronger stuff than would have commonly been drunk (mixing measurements are exhaustively discussed at Ath. 10.426b–427d). Such a call for drinks attempts to mirror and even surpass an exuberantly drinking lyric poet like Alcaeus: really living it up now. Then again, the Homeric hapax and all the philological baggage that comes with it underlines the written medium of the poem: this is emphatically a poem of reading and writing rather than singing symposiasts.

Apollonides was not the only one who made much of the word ζωρός in the first centuries ʙᴄ and ᴀᴅ. His contemporary Marcus Argentarius exhorts in a carpe diem poem to taking a ‘neat cup of wine’ (Βάκχου ζωρὸν δέπας). Set in a decidedly Roman setting, in which a wife can take part in a banquet, the epigram gives us a literary version of the sentiment of the Boscoreale cups. Let us enjoy ourselves; all philosophy amounts to nothing as even famous philosophers die (AP 11.28 = 30 GP):

When you lie dead you’ll have five feet of land, and you will not see the pleasures of life or the rays of the sun. Therefore, grab a neat cup of Bacchus’ wine, down it, and be happy, Cincius, with your beautiful wife in your arms. But if you think that the mind of wisdom is immortal (?), keep in mind that Cleanthes and Zeno went down to deep Hades.

Marcus Argentarius alludes to a carpe diem epigram of Asclepiades, as he substitutes Asclepiades’ Βάκχου ζωρὸν πόμα for Βάκχου ζωρὸν δέπας in the same metrical sedes (‘neat drink [or “cup” in the other case] of Bacchus’ wine’).Footnote 48 Argentarius also follows Asclepiades’ lead in making an etymological pun on the Homeric ζωρός. In his epigram, the exhortation to drink Βάκχου ζωρὸν δέπας is a direct result (ὥστε) of the insight that after death one is unable to see the ‘pleasures of life’ anymore (τὰ τερπνὰ ζωῆς). The ‘neat wine’ (ζωρός) thus equates to ‘life’ (ζωή) and, by suggesting this equation, Argentarius follows Homeric scholia, which define ζωρότερον in Iliad 9 as ἀκρατότερον, παρὰ τὸ ζῆν (‘unmixed, deriving from living’).Footnote 49 Argentarius takes this witty etymological play from Asclepiades, where Richard Hunter has already identified the same learned allusion to Homeric scholarship (AP 12.50.4–5 = 16.4–5 HE):Footnote 50 τί ζῶν ἐν σποδιῇ τίθεσαι; | πίνωμεν Βάκχου ζωρὸν πόμα (‘why are you lying in ash, although you are alive? Let’s drink the neat drink of Bacchus’ wine’). Perhaps Asclepiades and Argentarius still wish to live it up and drink like Homer’s feasting hero, but this manner of drinking now needs glossing. The etymology of a Homeric crux makes ζωρός a crucial term for carpe diem. For if the study of Homer shows that unmixed wine is related to life, then we can truly say with Trimalchio, uinum uita est (Petron. 34.7), and indulge in the idea of carpe diem.

The etymology of ζωρότερον was still known to Martial. In one of his epigrams, a Roman snob boasts that his collection of old drinking vessels contains, among other items, also the cup of Nestor and the very cup of Achilles from Iliad 9 (8.6.11–12): hic scyphus est in quo misceri iussit amicis | largius Aeacides uiuidiusque merum (‘this is the cup in which Aeacus’ grandson Achilles told his friends to mix a more generous and neater mixture, a veritable eau de vie’). In Martial, largius translates Homer’s μείζονα, while merum translates ζωρότερον. As has been recognised, Martial, too, like the Greek epigrammatists, glosses the supposed etymology of ζωρότερον from ζῆν by associating ‘unmixed wine’ (merum) with a ‘livelier’ mixture (uiuidius).Footnote 51 Achilles’ drinking vessel becomes, at least in the imagination of Martial’s snob, a physical object that is present at the banquet.Footnote 52 Though the collection of Martial’s snob is absurd, it seems that there existed people in the ancient world who imagined that they owned physical drinking vessels of Homeric heroes. Thus, the learned Athenaeus tells us that the people of Capua in Campania believed that they had the genuine cup of Homer’s Nestor in their city – a cup that Martial’s collector of course owns as well (Mart. 8.6.9–10).Footnote 53 In his treatment of Achilles’ cup, Martial’s collector shows some interest in Homeric scholarship, but he does little to live up to the Homeric ideal: instead of Achilles’ strong mixture, he serves some unimpressive young wine in his precious cups. This is most emphatically not the idea of carpe diem. Martial points to some dissonance between the object as an object and as a sign: while Achilles’ cup is suggestive of a splendid symposium from the past, it has become a dusty object in a collection. It works as a signifier but has lost its function as an object.

While Martial’s snob claims that his collection also includes a krater that was damaged in the battle of Lapiths and centaurs (8.6.7–8), Pliny the Elder tells us of a different and particularly fascinating broken cup in a collection of precious vessels (Nat. 37.19). In a section on Myrrhine vessels, Pliny notes their exceptional value, saying that one single cup of this material was valued at 70,000 sesterces.Footnote 54 An ex-consul was particularly fond of these vessels, and after Nero had confiscated the collection of cups from this man’s children he displayed them in a private theatre in the horti Neronis. There Nero would sing in front of a large audience when he was rehearsing his performances, which were designated for an even larger audience at the theatre of Pompey. Pliny says that he himself saw that even the pieces of a broken cup were added to the collection and presented like a corpse, so that it might show the ‘sorrows of the age and the ill-will of Fortune’ (Nat. 37.19):Footnote 55

uidi tunc adnumerari unius scyphi fracti membra, quae in dolorem, credo, saeculi inuidiamque Fortunae tamquam Alexandri Magni corpus in conditorio seruari, ut ostentarentur, placebat.

At this time, I saw the pieces of a single broken cup added to the exhibition. I believe it was decided to keep these pieces for display in a coffin – just like the body of Alexander the Great – as signs of the sorrows of the age and the ill-will of Fortune.

It seems that Pliny was among the spectators of one of Nero’s performances, as he presents the story as an eye-witness account of himself.Footnote 56 Pliny tells us not only what he sees, but he also informs us of the motifs behind the display of the odd object. It is difficult to ascertain to what extent this actually represents Nero’s motivation or merely Pliny’s imaginative interpretation. The qualification credo may hint at some guesswork of Pliny. Yet, whether we can discern Nero’s staging of cups or Pliny’s reception, either way we gain valuable insights into first-century views on cups.

Ida Gilda Mastrorosa thinks that Pliny wishes to underline Nero’s decadence and the extravagant form of his collection.Footnote 57 The object is indeed most unusual and makes for a unique collection: why would one want to display shards of a cup? Yet, what Nero does here (or what Pliny ascribes to him) is rather witty and only understandable through the practice of displaying skeleton figurines at the symposium, as Trimalchio does in the Satyrica (Petron. 34.8).Footnote 58 The coffin also belongs to this motif, but instead of a human skeleton we find a broken cup inside. As a sign for enjoyment and drinking, its likening to a human being is a strong reminder to enjoy life while one can. Such an object is well placed in a performative space, in which Nero played the lyre. All this makes for rather exciting evidence: at least if we can trust Pliny, Nero, like Domitian, was another ruler of the first century ᴀᴅ who staged carpe diem (see the next section of this chapter for a carpe diem epigram of the Roman client king Polemon).

Though the broken cup of Nero’s collection is unique, there is at least one piece that comes close to it and offers further support for seeing a carpe diem motif in this cup. For in Petronius’ Satyrica we can also find a broken wine vessel in a funerary context. When Trimalchio describes his future tomb, he wishes it to feature sealed amphorae containing wine, and a carving of one of them broken, with a crying boy weeping over it (Petron. 71.11: amphoras copiosas gypsatas, ne effluant uinum. et unam licet fractam sculpas, et super eam puerum plorantem).Footnote 59 While Pliny describes a broken wine cup in a coffin, Trimalchio wants to have a carving of a broken amphora in his tomb. The message is arguably the same in Trimalchio’s case – one should drink wine while one can (that is, while one is alive or as long as the amphora is intact). Thus, Trimalchio’s lesson from the extended description of his last will and tomb is to live it up (Petron. 72.2): ergo […] cum sciamus nos morituros esse, quare non uiuamus? (‘so, as we know that we will die, why shouldn’t we live it up?’).Footnote 60

Perhaps Nero’s shattered cup best exemplifies Barthes’ ‘semantization of the object’;Footnote 61 for the shattered cup has no practical function anymore and is still framed as a sign for the banquet (this is similar to the sign system of musical notes on the Seikilos epitaph discussed in the Introduction). Even without function the cup evokes luxury, revelry, and pleasure. The functionless cup is a proper zero-degree symbol; if within the semantics of cups a cup’s morpheme is that one can drink from it, then Nero’s zero-degree cup has lost its morpheme, but still creates meaning as part of a system of signs. At the same time, Pliny’s account puts a strong emphasis on the cup’s material: though the cup has lost its form, its precious material still evokes luxury.

4.2 Gems

Nero’s broken cup from the last section is included in a book on gems and stones in Pliny’s Natural History, since it was made from myrrhine. There is an interesting overlap between gems and cups. For example, epigrams on gemmed cups are also included in the section λιθικά (‘stones’) in a collection of Posidippus’ epigrams (2, 3 Austin and Bastianini). Indeed, the papyrus discovery of the New Posidippus and its epigrams about stones also changes how we interpret other epigrams on gems. Notably, Évelyne Prioux has fruitfully interpreted Posidippus’ λιθικά as a precious collection of epigrams, which mirrors real gem collections that Ptolemaic rulers may have possessed, and Prioux has applied some of the lessons from the New Posidippus to epigrams of other authors.Footnote 62 The following section will look at gems and epigrams from the late Hellenistic period and the Roman Principate which include the carpe diem motif. Taking into account the importance of epigrams about stones, which we learned from the New Posidippus, I will analyse how epigrams respond to artworks on gems and how the carpe diem motif becomes treated as a luxury and simultaneously a justification for luxury in these media.Footnote 63

Crinagoras, whose epigrams are included in The Garland of Philip, was an influential citizen from Mytilene, who served as an envoy to Rome on at least three occasions.Footnote 64 Two of these embassies approached Julius Caesar, the third one Augustus in Spain in 25 ʙᴄ. It seems that Crinagoras spent substantial time in Rome after his third embassy and was an intimate friend of the family of the Princeps, as attested to by epigrams for Antonia (AP 9.239 = 7 GP, AP 6.244 = 12 GP) and Marcellus (AP 6.161 = 10 GP, AP 9.545 = 11 GP). Crinagoras’ epigrams thus offer a fascinating Greek voice from the circle around the Princeps, which is too often ignored when scholarship focusses on the likes of Horace and Vergil.

The following epigram of Crinagoras leads from a description of a skull on the wayside to a carpe diem exhortation (AP 9.439 = Crinagoras 47 GP):Footnote 65

5 κεῖσο κατά Sternbach : κεῖσο πέλας κατὰ PPl παρ’ ἀτραπόν P : παρὰ πρόπον Pl μάθῃ τις suppl. Jacobs : τις εἴπῃ suppl. Griffiths

Skull that was hairy long ago, deserted shell of the eye, frame of a mouth without a tongue, weak fence of the soul, remains of an unburied dead, cause for tears of passers-by at the wayside, lie there under the tree stump beside the path that <one> may look at you and <learn> what gain there is for someone who is sparing of his means.

There is not a single finite verb in the first four lines; instead, there is a list of nouns that describe the skull. Crinagoras employs some recondite words and metaphors, but he essentially draws an anatomy of a skull, consisting of cranium (without hair), eye sockets (without eyes), joint of the jaws (without tongue), and teeth (without soul). Constantly, this anatomy underlines what the skull is not: a living human. The descriptive nature of the epigram is further underlined by the participle ἀθρήσας (‘looking on’) in line 6: the sight of the skull is focalised through someone who looks at it. The descriptive style of the epigram, which draws the scene featuring skull, tree-stump, path, and passer-by who looks at the skull and cries, seems to ask for parallels in art. Indeed, Nikolaus Himmelmann has pointed to the parallels between this epigram and a number of second- and first-century-ʙᴄ Roman-Etruscan gems which show shepherds looking at a skull on the wayside in an exhortation to carpe diem.Footnote 66 As Himmelmann has shown in detail, these gems may have inspired the imagery of Guercino’s famous painting Et in Arcadia ego, and for this intriguing insight alone the article surely deserves more readership.Footnote 67 While Crinagoras’ epigram describes a lifeless skull, this image is contrasted with the material that we are arguably invited to imagine: a gem that may be gleaming with inner life.Footnote 68 Image and material constitute an antithesis, then, of death and life, poverty and luxury.

Crinagoras’ epigram describes numerous features which can be found on gems (Figures 4.3–4.5): naturally, the skull itself and the chance wanderer who looks at it. But even the details are paralleled on gems; thus, gems regularly show the skull below a tree-trunk (Figures 4.4 and 4.5(a) and (b)),Footnote 69 and one gem shows a shepherd raising his head, which Himmelmann interprets as gesture that shows shock and sadness (Figure 4.3).Footnote 70 In the epigram, such a reaction is implied in the description of the skull as a ‘cause for tears of passers-by at the wayside’. Finally, gems sometimes depict a bee, fly, or butterfly over the skull, which represents the soul (Figures 4.5(a) and (b)).Footnote 71 The epigram describes the skull, or perhaps more specifically its mouth and teeth, as ‘weak fence of the soul’ (ψυχῆς ἀσθενὲς ἕρκος). The word ψυχή can mean butterfly or moth as well as soul.Footnote 72 Thus the idea of a weak fence of the soul may also evoke the image of a butterfly which easily escapes from the skull, as can be seen on some gems. It should be clear by now that the epigram is indeed a description of a gem, or more specifically of an Italian gem, which Crinagoras probably saw during one of his embassies in Rome.Footnote 73 Indeed, we know from Pliny that Marcellus, with whom Crinagoras conversed in Rome, owned a gem collection, which he dedicated to the temple of Apollo on the Palatine (Nat. 37.11).Footnote 74

Figure 4.3 Berlin Gem with shepherd and skull

Figure 4.4 Munich Gem with shepherd and skull

Figure 4.5(a) Copenhagen Gem with shepherd and skull

Figure 4.5(b) Copenhagen Gem with shepherd and skull (imprint)

Several epigrams of Crinagoras are literary accompaniments of little luxurious gifts, similar in fashion to the Apophoreta of Martial (see Crinagoras 3–7 GP). These epigrams on objects such as a silver pen, an Indian bronze oil flask, or book editions of Anacreon and Callimachus can give us an impression of fashionable luxury objects at the Augustan court. This is also true for the epigram on the wayside skull. The circle around Augustus would have recognised a description of a gem in this epigram, and Marcellus perhaps even possessed such a gem. In the last line, the epigram asks what good it is to be thrifty: τί πλέον φειδομένῳ βιότου. The sentence is strikingly similar to the first words of a carpe diem poem of Asclepiades, as Maria Ypsilanti notes (AP 5.85 = 2 HE):Footnote 75 φείδῃ παρθενίης. καὶ τί πλέον; (‘you are saving your virginity. But what is there to gain?’). The allusion strengthens the carpe diem motif in Crinagoras’ epigram. Indeed, the word φείδομαι (‘to spare’) is common in carpe diem poems, which tell their addressees not to be sparing with their money, their wine, their sexual favours, and so on.Footnote 76 These different categories are easily conflated, and Crinagoras’ epigram seems to warn against both attaching too much importance to one’s life and being too thrifty with one’s means.Footnote 77 If we consider again that this epigram represents a luxurious gem, the question also reinforces a message that the purposed material already gives – anyone who owns such a precious piece knows very well how not to be thrifty but spend money on precious objects.

Another epigram, attributed to Polemon II, a Roman client king of Pontus, makes the ekphrastic connection between a gem and an epigram explicit, by describing a gem that shows a loaf and flagon, a garland, a skull, and an inscribed carpe diem message (AP 11.38 = Polemon 2 GP):

Here is the welcome equipment of beggars, their bread and flagon, and here is a garland of dewy leaves, and here is a sacred bone, the suburb of the dead brain, the highest citadel of the soul. ‘Drink’, the engraving says, ‘and eat and garland yourself with flowers; suddenly we will be like this’.

Like Crinagoras’ epigram on the wayside skull, the first four lines of this epigram also consist of a list of nouns without any finite verb, describing an artwork, before again the third couplet provides a carpe diem message as an interpretation of the artwork. The first four lines are described by Gow and Page as ‘pompous and insipid’.Footnote 78 But what exactly do these lines describe? Évelyne Prioux says that this epigram is ‘the description of a sardonyx engraved with the typical belongings of a beggar’.Footnote 79 Yet, neither garlands nor skulls can be considered typical possessions of beggars. Rather, the epigram describes three different sets of items, and presents them as thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. The word ἀρτολάγυνος – whether this is a ‘bag with bread and bottle’ (so LSJ) or ‘equipment comprising loaf and flagon’ (so Gow and Page) – basically describes a beggar’s banquet, and ἡ πτωχῶν χαρίεσσα πανοπλίη only refers to this item.Footnote 80 The next item, the ‘garland of dewy leaves’, stands for a contrasting type of banquet, a luxurious symposium. The third item, the skull, shows that, either way, one will be dead, whether one lives sparingly or in luxury. A well-known magnificent mosaic, set in a table at a Pompeian triclinium, makes very much the same statement.Footnote 81 It shows a skull, which sits on a wheel of fortune and over which two sets of items are balanced. One consists of a king’s sceptre, diadem, and purple, the other one of a beggar’s staff, pouch, and ragged cloth. Nonetheless, Polemon is not associating himself with beggars or foregrounding ‘the Cynic motif of the beggar’, as Prioux wants it.Footnote 82 Rather, Polemon makes very clear which of the two dinners – beggar’s banquet or garlanded symposium – one should choose by exhorting the reader to go for garlands (περίκεισο ἄνθεα).

The last couplet can also be found on a now-lost gem, illustrated by Antonio Gori (Figure 4.6), which shows a skull above the epigram and a table below it (CIG 7298 = Kaibel 1129).Footnote 83 Prioux argued that the gem might be a modern forgery inspired by Polemon’s epigram, as the gem was not known before the seventeenth century and as its loss makes it impossible to determine its authenticity with certainty.Footnote 84 But if a forger was inspired by the Greek Anthology, would he not rather have chosen to depict the items mentioned in the epigram (bread, bottle, garland, skull), instead of a table? Following Robert Zahn and Katherine Dunbabin,Footnote 85 I think it is more likely that the gem is authentic. Indeed, the authentic Leiden gem, discussed below, offers a parallel for a similar phrase that is put on a gem along with an image. There are several other gems that show similar motifs to the ones described in Polemon’s epigram.Footnote 86 One gem, which depicts a skeleton, a butterfly, a jug, and a loaf or a patera, also features the inscription κτῶ χρῶ (‘acquire and use’).Footnote 87 Such simple, inscribed gems may have been the source for the more elaborate epigrams discussed in this chapter. The same idea is also expressed on a very curious gem that is now lost, though there exists an etching by Antonio Boriani with a commentary by Rodulphino Venuti (Figure 4.7).Footnote 88 Venuti claims that the gem included an inscription of a proverbial saying from Cicero, in which Cicero says that the best soothsayer is the one whose guesswork is best (De Div. 2.12; same saying in Greek at E. TrGF 973). If the gem actually included this inscription (presumably on its back), it would make for exciting evidence: Epicurus’ distrust in divination was well known (frr. 15, 212 Arrighetti), and it is easy to see how such a sentiment could appeal to the idea of carpe diem in popular Epicureanism. Indeed, we can see similar statements in Horace’s carpe diem poems (C. 1.11.1–2, 3.29.29–32; also AP 11.23.1–2 = Antipater of Thessalonica 38.1–2 GP). Yet, it is also easily conceivable that a proverbial quotation of perhaps the most canonical author of antiquity might be a modern addition, and as the gem is lost it is not possible to examine the inscription itself.Footnote 89

Figure 4.6 Lost gem with skull, table, and inscription

In Polemon’s epigram, the last couplet is the inscription proper and marked as such (λέγει τὸ γλύμμα; ‘the engraving says’),Footnote 90 whereas the two previous couplets offer a description of the gem’s visual features. These two couplets are redundant on the gem of Gori, where images are present and need no description. This may help to explain the ‘marked contrast between the bombast of the first four lines and the forceful simplicity of the last two’, which Gow and Page notice.Footnote 91 The simplicity of the last lines points to its heritage in inscribed epigrams on carpe diem. The first two couplets, however, do not reflect the language of inscribed epigrams, but with their affected bombast perhaps attempt to mirror the luxury and value of the artwork with rare words. As the epigram represents both images and inscription by words, it chooses a jewelled style for the representation of the gem’s visual features. It thus contrasts the descriptive nouns that lack verbs in the first four lines with the urgent sequence of three verbs in the imperative in the fifth line: πῖνε […] καὶ ἔσθιε καὶ περίκεισο ἄνθεα (‘drink […] and eat and garland yourself with flowers’).Footnote 92

The epigrams of Crinagoras and Polemon and the gems that depict the same subjects thematise luxury. To be sure, not all ancient gems are equally luxurious. Some ancient gems were glass pastes. Yet, the gem Polemon describes is most naturally imagined to belong to his royal gem collection and be highly valuable. Gori’s lost gem that includes part of Polemo’s epigram is a sard. Among the first-century-bc Roman gems that inspired Crinagoras’ epigram we also find sard or carneol, the most common gem in antiquity.Footnote 93 In the next paragraph, we will encounter an agate, a stone that used to be of great value, but was apparently not anymore in Pliny’s time (Nat. 37.139). Though the precise value of individual gems may vary, then, texts and gems in this chapter all argue in favour of spending while one is alive and take gems as a sign for luxury.Footnote 94 In the first centuries ʙᴄ and ᴀᴅ, carpe diem was a motif fashionable enough to be treated through luxurious objects, such as gems, cups, and dinner tables, and epigrams interact with these objects. Carpe diem even becomes the justification for the existence of such objects; the gems are minute pieces with maximum price tags, zero-degree signs of luxury, so to say, but this extreme form of spending is justified by the admonitions that there is no use in thriftiness after death. Life is short, so spend and don’t be greedy! When gems proclaim this, the exhortation’s success is almost guaranteed. The reader, most likely the owner of the gem, did in fact spent a fortune on a little stone and holds this very stone in his hand as he reads the inscription. Epigrams, in describing such gems, aim to evoke luxury of this kind by means of ekphrasis.

The final example in this section will again combine several media: it is an extant gem, which features both an image and a text (Figure 4.8). The late Hellenistic gem, plausibly dated to the first century ʙᴄ and now in Leiden, shows both an engraving that exhorts to carpe diem and an image that underlines this message. The Leiden gem, an agate, has the following inscription in its upper part (Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Inv. GS-01172 = CIG 7299):Footnote 95

Πάρδαλα, πεῖ|νε, τρύφα, περιλά|μβανε. θανεῖν σε | δεῖ. ὁ γὰρ χρόνος | ὀλίγος.

Leopard, drink, live in luxury, hug! You must die; for time is short.

The lower part of the gem shows two men having intercourse on a couch, and below this image the text reads:

Ἀχαιέ, ζήσαις.

Greek man, may you live it up!

Figure 4.8 Gem with image of lovers and inscription

In a fascinating analysis of the gem, John Clarke observed that the penis of the penetrated man is large and erect, which finds no parallel in artistic representations of intercourse between two men.Footnote 96 Clarke goes on to show that the perspective of the image is even designed to highlight this unique detail, and he assumes that this gem is a custom-made piece, which allows us a rare look into the love life of an individual couple from the ancient world: it shows love and tenderness between two men of similar age rather than Hellenistic cultural constructions of roles in man-to-man intercourse.

Compared to the unique image, the text of the carpe diem exhortations first seems commonplace. Several parallels can be found in literary epigrams, more in inscribed epitaphs.Footnote 97 One inscription offers the same sequence of imperatives (SGO 02/09/32.5):Footnote 98

ὡς ζῇς εὐφραίνου, ἔσθιε, πεῖνε, τρύφα, περιλάμβανε·

While you live, enjoy yourself, eat, drink, live in luxury, hug!

Furthermore, the sentence θανεῖν σε δεῖ on the Leiden gem finds a parallel in an epitaph (GV 1016.5),Footnote 99 and the observation that time is short can be found very similarly expressed in a fragment of Amphis (fr. 8: ὀλίγος οὑπὶ γῇ χρόνος; ‘time on earth is short’), all in the context of carpe diem. But rather than the text itself, which is conventional, the engagement between text, image, and material on the Leiden gem is fascinating. Thus, Ann Kuttner has ingeniously suggested that the ‘oval, banded agate glosses the nickname “Leopard” by resembling the animal’s spots’.Footnote 100 Indeed, it can be added to Kuttner’s suggestion that Pliny tells us of certain agates that are said to resemble lions’ skin (Plin. Nat. 37.142). Two of the three imperatives on the Leiden gem also relate to material and image. For the exhortation to live in luxury (τρύφα) points to the luxury of the gem, and the admonition to hug (περιλάμβανε) refers to the activity on the image.

Clarke prints the inscription as a continuous text. But perhaps more attention should be paid to the arrangement of text and image on the gem, which, in fact, presents the text above and below the image. This arrangement makes an old suggestion of D’Ansse de Villoison from 1801 attractive, who understood the text as a dialogue between two lovers, respectively addressed as Πάρδαλα and Ἀχαιέ.Footnote 101 The change of addressee within three sentences makes it unlikely that they are all spoken by the same person and addressed to a single addressee. Indeed, the two vocatives which stand at the beginning of each text section highlight the change of addressee. Therefore, the upper part of the text is most naturally assumed to be spoken by the man who is lying on top of the other one. Then the man lying below answers him, and his answer is written below him. The arrangement of above and below does not only apply to the text and the lovers’ bodies but also to the very material of the gem: a lighter stripe of the agate separates two darker parts above and below.Footnote 102 The gem supplies one more hint that supports the interpretation of this as a dialogue. Clarke stresses that the mutual gaze of the two male lovers during intercourse is rather exceptional in art.Footnote 103 This striking gesture also becomes better understandable if we see the two lovers speaking to each other.

To some extent, the Leiden gem allows us a glance at the sort of artwork the epigrams of Crinagoras and Polemon are mimicking. Here, the imperative τρύφα (‘live in luxury’) is written on a luxurious gem as part of a carpe diem exhortation, and whoever owned and read the gem could perceive the presence of luxury whenever he read the exhortation.Footnote 104 But the implications of the gem go further still. For the gem also shows us how texts can give a closer rendition of present enjoyment when they interact with visual art. Together, text and image show a dialogue of two lovers in the very act of utmost enjoyment. It can be assumed that the owner of the gem felt aroused whenever he looked at it. Materiality, imagery, and text of the gem reinforce one another: as the gem exhorts to present enjoyment it evokes the presence of an ecstatic moment. Image and material help a rather hackneyed text to bridge the gap to present enjoyment.

4.3 Dining Halls and Tombs

In the past two sections, I have looked at individual objects, cups and gems respectively, and I have considered their quality as signs. In the section that follows, I will look at combinations of objects. Roland Barthes notes that the syntax of objects, their syntagma, is comparatively simple; it consists of the parataxis of objects, that is, some objects are juxtaposed.Footnote 105 The two objects that interest me here are dining halls and tombs. I will analyse what happens when we find these two objects in close spatial proximity, either in the city space or on the page of a book. I will analyse how the parataxis of objects can evoke the carpe diem motif.

The following epigram of Martial purports to be an inscription of a dining hall. The sight of Augustus’ mausoleum from the dining hall leads to an exhortation of carpe diem (2.59).Footnote 106

I am called ‘the Crumb’. You can see what I am: a small dining hall. Look! From me you look out on the dome of the Caesars’ mausoleum. Throw yourself upon the cushions of the couches, ask for wine, get roses, soak in nard. The god himself asks you to remember death.

By now the structure of such epigrams looks rather familiar; again, a description (here consisting of one couplet) is followed by an exhortation and a lesson in the next and final couplet.Footnote 107 As in Crinagoras’ and Polemon’s epigrams, the first couplet marks Martial’s epigram as literary. For the description, quid sim cernis, cenatio parua (‘you can see what I am: a small dining hall’), would have been superfluous in an inscribed epigram. In this description, Martial conjures up the sight of the two objects: he wants us to ‘see’ (cernis) the dining hall, and he wants us – ‘look!’ (ecce) – to ‘look out’ (prospicis) on the mausoleum of Augustus; the two objects materialise before our eyes. The third line, in contrast, constitutes the inscription proper of the epigram; inscribed parallels can easily be found, and one could indeed imagine such a line inscribed on the wall of a dining hall (which is, of course, not the same as assuming that the epigram was in fact inscribed). This type of inscription would be equally appropriate for tombs and dining halls, two vastly different places, which are juxtaposed in Martial’s epigram.

Juxtaposition was identified as an important element of Martial’s epigram books by William Fitzgerald.Footnote 108 Adducing nineteenth-century developments such as the newspaper or the figure of the flâneur, Fitzgerald sees Martial’s technique of authorial juxtaposition as a mirror of a varied urban landscape.Footnote 109 Though Fitzgerald himself admits that juxtaposition as an authorial decision is a concept as difficult to prove as it is to disprove, there is much to say in favour of this theory. Indeed, if it can be shown that Martial also juxtaposes contrasting topographical features of the city within the same epigram, this might add further weight to Fitzgerald’s argument. Or, in other words, are there epigrams of Martial which describe the city-space as a combination of differences, similar to the arcades or department stores of nineteenth-century Paris, which consisted of a combination of different shops or objects?Footnote 110 One category of juxtaposition in Martial, which Fitzgerald highlights, is the juxtaposition of social orders.Footnote 111 An example where this juxtaposition of social orders is mirrored by a juxtaposition of places is Epigrams 2.57. This is a biting social commentary, which first presents a parvenu strolling through the Saepta Julia, a ‘favourite strolling ground and social showcase’,Footnote 112 but in the end shows him in a pawnshop, at Cladus’ counter (Cladi mensam).Footnote 113 Fashionable strolling grounds and pawnshops are spaces that are closely juxtaposed in Rome, and as Martial shows the parvenu first in one place and then in the other, we move through different social orders, as we move through the city.Footnote 114

The concept of topographical juxtaposition also applies to Martial 2.59 on the mica; it tells of two places, a mausoleum and a dining hall. Their proximity in the urban landscape and their contrast in function brings about the message in the second couplet. A flâneur could pass the two sights in quick succession and develop thoughts similar to Martial’s, or he could save himself the bodily exercise and actually see the mausoleum already from the dining hall. When the cityscape offers juxtapositions of tombs and dining halls, of death and booming life, and when such sights also feature epigrams, then the city itself already constitutes a text of juxtaposed epigrams, and all Martial has to do is transcribe Rome, as it is already inscribed.Footnote 115

Scholars have long seen the similarity to another epigram of Martial, in which the mausoleum of Augustus again invites thoughts of carpe diem (5.64):

Callistus, fill two large cups with Falernian wine. Alcimus, melt summer snow over the cups. My hair should become oily and wet with too much perfume, and my temples should become exhausted with the weight of stitched roses. The mausoleum, which is very close, tells us to live it up, as it teaches that even the gods themselves can die.

Though here only one topographical marker is explicitly mentioned, namely the mausoleum, the presence of the dining hall is implied in the setting of the first four lines. Indeed, Fitzgerald has alerted us to the significance of the word uicinus in Martial’s epigrams,Footnote 116 which here once more highlights a juxtaposition: ‘the mausoleum, which is very close, tells us to live it up, as it teaches that even the gods themselves can die’. Life and death are neatly juxtaposed in one neighbourhood.

It is significant that Martial makes the carpe diem argument through a combination of objects, namely of a dining hall and a tomb. This combination can be described as juxtaposition in Fitzgerald’s term or as parataxis and syntagma, in the terms of Barthes. Juxtaposition here creates spatial closeness between semantically contrasting objects. Or, simply put, the juxtaposition says: ‘A dining hall is not a tomb.’ This might seem obvious, but it shows how objects act as signs. Both signs have different meanings, and the simple combination of two signs or objects with contrasting meaning creates the carpe diem motif: because dining halls are not tombs, we have to enjoy the present moment.

Sometimes the juxtaposition of dining halls and tombs expresses identity between the two objects, resulting in a sentence that stresses the opposite: ‘a tomb is a dining hall’. This is, for example, the case with the tomb of Cornelius Vibrius Saturnius, found in Pompeii. His tomb features an impressive funerary triclinium, which along with similar monuments points to beliefs that the dead could still drink – a belief that was commonly expressed through the Totenmahl motif in the ancient world.Footnote 117 Not only did Cornelius Vibrius Saturnius find the thought of a tomb as a dining hall appealing, but Petronius’ Trimalchio, too, envisages a tomb for himself that will feature dining halls (triclinia). Indeed, the Cena Trimalchionis offers a particularly detailed juxtaposition of tomb and dining hall. This juxtaposition begins long before Trimalchio’s ekphrasis of his tomb. For already before the dinner starts, a wall painting in Trimalchio’s house has the appearance of the type of wall painting one would find in a tomb (Petron. 29).Footnote 118 But, just as Trimalchio’s house already looks much like a tomb (Herzog: ‘Totenhaus’), the detailed ekphrasis of the tomb that Trimalchio planned for himself makes the tomb look much like a dining hall. In this ekphrasis, Trimalchio describes features of his tomb, including his own statue, several other statues, the tomb’s size, the surrounding orchard and vineyard, a relief that shows a dining scene, a sundial, and two inscriptions (Petron. 71.5–12). In this passage, the juxtaposition of dining hall and tomb becomes most marked. Trimalchio asks, for example, that his tomb may also depict dining halls (71.10):Footnote 119 faciantur, si tibi uidetur, et triclinia. facias et totum populum sibi suauiter facientem (‘and also make some dining halls (if that seems good to you). And show all the people having a great time’).Footnote 120

As soon as Trimalchio had finished his speech, he, his wife, Habinnas, and his household ‘filled the dining hall with lamentation, as if invited to a funeral’ (Petron. 72.1): haec ut dixit Trimalchio, flere coepit ubertim. flebat et Fortunata, flebat et Habinnas, tota denique familia, tamquam in funus rogata, lamentatione triclinium impleuit. As the dining hall (triclinium) becomes a funeral space, and as the tomb features a dining space (triclinia), the architecture of the two spaces is thoroughly confused:Footnote 121 the dining hall becomes tomb and vice versa. What needs stressing is how the ekphrasis recreates the materiality of the tomb: as Trimalchio quotes the epigrams that will be written on his tomb, and as he describes numerous architectural features, the words that describe his tomb become an object. And though Trimalchio’s ekphrases elsewhere might be considered notorious rather than impressive (Petron. 52.1), in the present case he might very well succeed in creating an object through words, as the dinner participants already have such an object before their eyes: sitting in Trimalchio’s Totenhaus makes it easy to see a tomb in front of you. Through the ekphrasis and the setting of the dinner, Trimalchio thus also shows us a combination of two objects: dining hall and tomb. And while he certainly underlines the similarity and, indeed, interchangeability of the two objects and thus seems to pronounce that a ‘dining hall is a tomb’, Trimalchio ultimately wants to have it both ways; for, in the end, the careful staging of objects leads to an exhortation of carpe diem, which implies that a tomb in the end is not quite like a dining hall after all (Petron. 72.2): ergo […] cum sciamus nos morituros esse, quare non uiuamus? (‘so, as we know that we will die, why shouldn’t we live it up?’).