When an individual appears in the presence of others,

there will usually be some reason for him to mobilize

his activity so that it will convey an impression to

others which it is in his interests to convey.

(Erving Goffman, Reference Goffman1959)

Of all the practices for reference to persons in

talk-in-interaction, the most common and the

most straightforward—at least for English—

appears to be self-reference.

(Emanuel A. Schegloff, Reference Schegloff, Enfield and Stivers2007b)

Introduction

In his pioneering study, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Goffman (Reference Goffman1959) describes how everyday actors present themselves so as to manage the impression they give others, and to contribute to the definition of the situations in which they participate. In the years since its publication, there has been a steady stream of investigations exploring the work of ‘impression management’ that Goffman first identified. One branch of this scholarship has examined its psychological dimensions, including its cognitive, motivational, and personality-related underpinnings and outcomes (see e.g. Jones Reference Jones1964; Baumeister Reference Baumeister1982; Jones & Pittman Reference Jones and Pittman1982; Leary & Kowalski Reference Leary and Kowalski1990; Seidman Reference Seidman2013; Leary Reference Leary2019). In contrast to the explicitly psychological orientation of that work, Goffman's own approach foregrounds sociological accounts of the structures of shared situations, rather than the psychologies of the individuals who populate them. This orientation is encapsulated in his assertion that ‘the proper study of interaction is not the individual and his psychology, but rather the syntactical relations among the acts of different persons mutually present to one another’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1967:2).

In developing this approach, Goffman focused on ritualized practices through which the self is constructed and displayed in interactions. Following his initial account of ritual self-presentation strategies in The Presentation of Self, Goffman (Reference Goffman1963) went on to describe how individuals who occupy stigmatized identities may work to manage the stigma by controlling the information they convey about themselves—for example, by concealing the discredited identity or ‘passing’ as a member of a non-stigmatized group. Subsequently, Goffman began employing the concept of face, in referring to ‘the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself by the line others assume he has taken during a particular contact’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1967:5), and described a set of face-work rituals through which participants manage impressions of themselves in situations in which their face may be threatened (also see Brown & Levinson Reference Brown and Levinson1987).

Recent work in this tradition has employed a range of theoretical and methodological approaches in continuing to build on Goffman's accounts of these ritual self-presentation practices, with this line of research including studies that examine self-presentation in relation to participants’ membership in and/or identities with respect to particular categories of persons. For example, Kang, DeCelles, Tilcsik, & Jun (Reference Kang, DeCelles;, Tilcsik and Jun2016) combine experimental and interview-based studies to describe how some racial minority job seekers may conceal or downplay racial cues in presenting themselves in job applications as a means of avoiding anticipated discrimination arising from their stigmatized racial identities; Baker & Walsh (Reference Baker and Walsh2018) use visual content analysis to examine how users on the social networking site Instagram employ a range of self-presentation techniques and styles in presenting their gender identities; and Davies (Reference Davies, Bamberg, Fina and Schiffrin2007) employs sociolinguistic ethnography to show how ‘bidialectal’ speakers of Southern American English use shifts between dialects to express different presentations of self (also see related discussions of Goffman's influence on studies of language and identity by, for example, Bucholtz & Hall Reference Bucholtz and Hall2008; Rampton Reference Rampton2009; Bullingham & Vasconcelos Reference Bullingham and Vasconcelos2013; Hall & Bucholtz Reference Hall and Bucholtz2013).

Despite Goffman's early disavowal of psychological accounts, Schegloff (Reference Schegloff, Drew and Wootton1988:95) contends that Goffman's ‘focus on ritual and face provides for the analytic pursuit of talk or action in the direction of an emphasis on individuals and their psychology. Although this is a very different psychology than the conventional ones, it is a psychology of individuals nonetheless’ (emphasis in original). In light of this, Schegloff (Reference Schegloff, Drew and Wootton1988:95) suggests that ‘the greatest obstacle to Goffman's achievement of a general enterprise addressed to the syntactical relationship between acts was his own commitment to “ritual”, and his unwillingness to detach such “syntactic” units from a functionally specific commitment to ritual organization and the maintenance of face’. In line with this appraisal, we offer one way to pursue Goffman's interest in self-presentation by focusing our attention on the elements of action formation, as opposed to individual psychology (also see Lerner Reference Lerner1996; Svennevig Reference Svennevig2014). Specifically, we show how speakers can employ particular conversational practices of self-categorization as a commonplace means of self-presentation.

Our approach to self-presentation rests on Sacks’ (Reference Sacks and Sudnow1972a,Reference Sacks, Gumperz and Hymesb, Reference Sacks1992; also see Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007c) pioneering investigations into the operation of membership categorization devices (MCDs), and especially of membership categories as ‘the store house and the filing system’ for common-sense knowledge about people (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007c:469). As Sacks (Reference Sacks and Psathas1979:13) notes,

What we have is a mass of knowledge known about every category; any member is seen as a representative of each of those categories; any person who is a case of a category is seen as a member of the category, and what's known about the category is known about them, and the fate of each is bound up in the fate of the other, so that one regularly has systems of social control built up around those categories which are internally enforced by members because if a member does something like rape a white woman, commit economic fraud, race on the street, etc., then that thing will be seen as what a member of some applicable category does, not what some named person did.

Membership categories can therefore be employed as an ever-ready adequate explanation for someone's behavior and beliefs:

That categorization which starts from some relevancies independent of a single action, permits you to go about, e.g., doing an explanation… what's involved now is not simply that one is proposing to have categorized it as the actions of such people, but to have explained it as well. If you can turn a single action into “a thing that they do”, it's thereby solved. (Sacks Reference Sacks1992:vol. I, 577)

Moreover, as Schegloff (Reference Schegloff and Fox1996b:459) notes, there is ‘an enormous inventory of terms for categories of persons’ (emphasis in original)—and there is always more than one way to refer to a person. Thus, a speaker's choice of a particular membership category from a particular collection in referring to a person can be inspected for what this contributes to the formation of the action in a turn at talk (see Schegloff Reference Schegloff and Fox1996b, Reference Schegloff2007a). Subsequent research (e.g. Kitzinger Reference Kitzinger2005a,b; Stokoe Reference Stokoe2009, Reference Stokoe2010; Whitehead & Lerner Reference Whitehead and Lerner2009; Lerner, Bolden, Hepburn,& Mandelbaum Reference Lerner, Bolden;, Hepburn and Mandelbaum2012; Whitehead Reference Whitehead2012, Reference Whitehead2013, Reference Whitehead2020; Fitzgerald & Housley Reference Fitzgerald and Housley2015; Raymond Reference Raymond2018, Reference Raymond2019a) has described some of the ways the use of membership categories can contribute to the actions formed up in conversation.

When it comes to self-reference, speakers, at least of English, ordinarily refer to themselves, as Schegloff (Reference Schegloff, Enfield and Stivers2007b:123) notes, through ‘the dedicated term “I” (and its grammatical variants—me, my, mine, etc.)’, which ‘is opaque with respect to all the usual key categorical dimensions—age, gender, status and the like’. As such, more-than-minimal self-references are especially accountable (Schegloff Reference Schegloff, Enfield and Stivers2007b:127). Indeed, West & Fenstermaker (Reference West and Fenstermaker2002) have shown that speakers can produce non-minimal self-references by employing the explicit self-categorizing format ‘speaking as an X’ (e.g. ‘speaking as a woman’ or as some other membership category or categories), and they suggest that such formulations ‘propose that speakers see themselves as accountable for their remarks in relation to their race category or race and sex category memberships’ (West & Fenstermaker Reference West and Fenstermaker2002:547–48; emphasis in original). Further, Land & Kitzinger (Reference Land and Kitzinger2007) show that speakers may also employ ‘third person’ forms as self-references that make explicit the relevance of particular membership categories in referring to themselves (e.g. a woman referring to herself as “that silly old bat that lives across the road from you”). Such ‘third person’ self-references are recurrently used as a way to represent the view of another (e.g. a recipient or even a non-present person), and as such can contribute to the action of the turn at talk (Land & Kitzinger Reference Land and Kitzinger2007). These findings exhibit the special interactional work speakers may do in the service of invoking their membership in a particular category, instead of simply referring to themselves. In doing so, speakers exploit the inference-richness of membership categories as a resource for self-presentation, and this can inform recipients’ understanding of the action produced in and as the speaker's turn at talk.

In this report, we add to this strand of conversation analytic research, and other work at the intersection of self-reference and membership categorization (e.g. Kitzinger Reference Kitzinger2007; Stokoe Reference Stokoe2009, Reference Stokoe2010; Jackson Reference Jackson, Speer and Stokoe2011; Lerner et al. Reference Lerner, Bolden;, Hepburn and Mandelbaum2012; Whitehead Reference Whitehead2013), by examining simple self-references (e.g. ‘I’, ‘me’, ‘my’, ‘mine’, etc.) that are ‘opaque with respect to all the usual key categorical dimensions’ (Schegloff Reference Schegloff, Enfield and Stivers2007b:123), but that are treated as too simple. That is, we consider instances in which speakers deploy practices that manage the possible categorical relevance of these simplest reference forms—thereby exposing speakers’ category-related concerns to both their co-participants and to analysts.Footnote 1 We begin by showing how speakers forestall their recipients’ possible attribution of category-relevance in relation to a simple self-reference by deploying practices that disclaim the relevance of any particular category for the action they are producing, or proceed to produce. We then consider cases in which simple self-references are subjected to subsequent elaboration via self-categorization in the face of category-related troubles—that is, instances in which speakers manage feasible misattribution of their category membership by converting a self-reference whose (possible) category-relevance was initially left tacit into an explicit self-categorization. Having demonstrated these explicit practices through which speakers manage the possible category-relevance of simple self-references, we then turn to the principal task of our report: a description of the practice of contrastive entanglement, which speakers can deploy to accomplish tacitly categorized self-references.Footnote 2

Data and method

The analysis we report here is part of our larger project on person reference in interaction that includes examination of both self-references and references to others (Whitehead & Lerner Reference Whitehead and Lerner2009, Reference Whitehead and Lerner2020). The data used in the project include a collection of legacy recordings produced over the course of several decades from the 1960s to the 2000s and shared among practitioners of conversation analysis (see discussion of these data in, for example, Kitzinger Reference Kitzinger2005b; Schegloff Reference Schegloff and Sidnell2009); other corpora produced by researchers and students within our institution, including the Santa Barbara Corpus of Spoken American English and the Language Use in Social Interaction (LUSI) corpus (collected by a consortium of CA researchers and students at several participating universities); and a set of recordings of South African radio call-in shows produced between 2007 and 2013 (see further discussion of this dataset in Whitehead Reference Whitehead2011). The present analysis is based on a collection of cases, assembled using the procedure described by Schegloff (Reference Schegloff1996a), in which speakers deploy practices designed to manage the possible category-relevance of simple self-reference.Footnote 3

The cases we examine first are drawn from the radio call-in dataset. In these instances, callers are speaking as anonymous strangers to the host, but also for an overhearing audience, having called to offer opinions on (often controversial) topics of general public interest. They do this by assessing, blaming, claiming, complaining, and the like (see Hutchby Reference Hutchby1996; Fitzgerald & Housley Reference Fitzgerald and Housley2002; Whitehead Reference Whitehead2011). This dataset proved to be a perspicuous setting for locating a range of practices used to establish an accountable basis for the opinion a caller expresses, so as to either give it more weight or to avoid it being discounted, including on the basis of the caller's membership in a particular category. (However, we do not expect that these practices will prove to be exclusive to this particular setting.) We then introduce the self-referencing practice of contrastive entanglement as the culmination of our report. Here too we include cases from this South African radio call-in dataset, but we also include cases from recordings of everyday telephone, dinner table, and backyard conversations among friends and families in the United States. The range of instances included in this section demonstrates that this practice—which can rely upon recipients’ grasp of the particular circumstances, parties, action sequence, and other features of its context of use—is deployed by speakers across a range of ordinary conversational and institutional interactional settings.

Forestalling the categorical relevance of simple self-reference

Sacks (Reference Sacks1992:vol. I, 180–81) has demonstrated that a speaker's position may be ‘explained away’ or discounted if they are heard to be a member of a category for which that position is category-bound (also see Watson Reference Watson1978; LeCouteur, Rapley, & Augoustinos Reference LeCouteur, Rapley and Augoustinos2001; Whitehead Reference Whitehead2020).Footnote 4 By contrast, Sacks also notes that a position taken by a speaker may be heard as ‘fully generalized’—‘hold[ing] for whomsoever’—if the speaker is taken to be ‘merely a person in this thing’ (Sacks Reference Sacks1992:vol. I, 196). That is, in contrast to practices for promoting a category-specific understanding of self, speakers can claim to be speaking only ‘as an individual’, or ‘as a human’, or ‘personally’, and not as a member or representative of any specific category. This can be seen in extract (1).

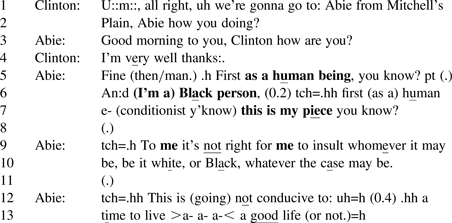

In this call, Abie, in contributing to a discussion of a controversial newspaper article that has been criticized as insulting to Black South Africans, explicitly claims to be speaking “as a human being” (line 5). This upfront claim, especially given the direct relevance of race to the topic at hand, reveals Abie's orientation to the possibility that, were he to begin without an explicit categorical disavowal, his opinion could be understood as implicating a category-bound stance—and the simple self-references at lines 7 and 9 might be (mis)understood as implicating Abie's membership in a racial category.

The position Abie formulates is not one, in the first place, addressed to the complainable matter at hand (that an article treats Black people in an insulting manner); rather, he is proposing a broader principle about insulting people in general, thus not formulating it as (just) a racial issue—although the racial matter at hand is subsumed under this general principle.

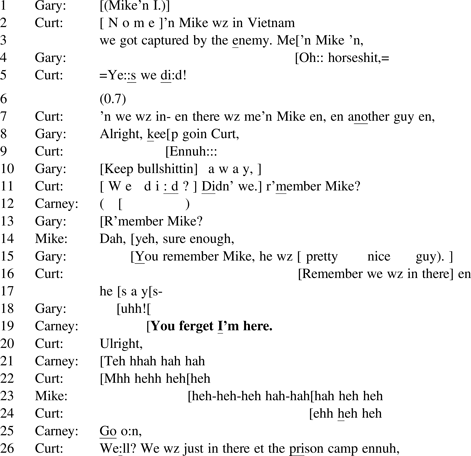

(1) [543, 702 4-23-08]

Shortly after describing himself as a “human being”, Abie then categorizes himself as a “Black person” (line 6), thereby explicitly treating this particular category as the one he would be vulnerable to being heard as speaking as a member of in the absence of his claims to be speaking “as a human being” (at lines 5 and 10). That is, he mentions race so as to disavow its relevance, in order to explicitly align his public persona with his upcoming stance as not racial, but human. He thereby casts the position he is headed toward formulating as one that any person might take, but concomitantly reveals that it will be a position that could be vulnerable to being understood as representing a racialized (and specifically “Black”) set of interests—and thereby discounted (see Sacks Reference Sacks1992; Whitehead Reference Whitehead2020). Moreover, he solicits alignment, or at least acknowledgement from the host (Clinton) of his formulation with “you know?” (line 7) before continuing on to assert his viewpoint (cf. Whitehead Reference Whitehead2013), although Clinton passes up the opportunity to produce such a response (line 8). Having established a ‘personalized self’, his subsequent simple self-references (“my” at line 7 and “me” at line 9) now can carry this forward as he offers his opinion.

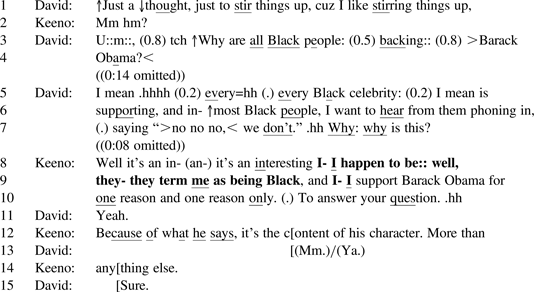

In extract (2), it is the host, Keeno, who backs away from a race category, already made relevant in a question from the caller, David (line 3). David's question uses the category “Black” as part of the extreme case formulation (Pomerantz Reference Pomerantz1986) “all Black people”, to challenge support for US presidential candidate Barack Obama, implying that this support is based solely on race, rather than being principled. In resisting this challenge, Keeno orients to, but distances himself from, his (generally known) membership in this category, and then goes on to formulate his answer so as to undercut the relevance of race in having come to the position he adopts.

(2) [602, 702 5-5-08]

In producing his response, Keeno initially concedes being Black, yet parries this designation by formulating it as incidental (“I happen to be”, line 8). He then further downplays its relevance for the matter at hand by asserting that his membership in this category has been attributed to him by others, thereby discounting its consequentiality for the support for Obama he goes on to assert (line 9). In this way, the subsequent simple self-reference (“I” at line 9) is protected (or even ‘inoculated’; cf. Edwards & Potter Reference Edwards and Potter1992) against categorical inference in relation to the racial category whose relevance he has just discounted. Keeno then underscores his resistance to David's racialized account by asserting a non-racial basis for his support of Obama by explicitly tying this claim to David's question (line 10) and invoking Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous ‘content of his character’ principle (line 12) in doing so.

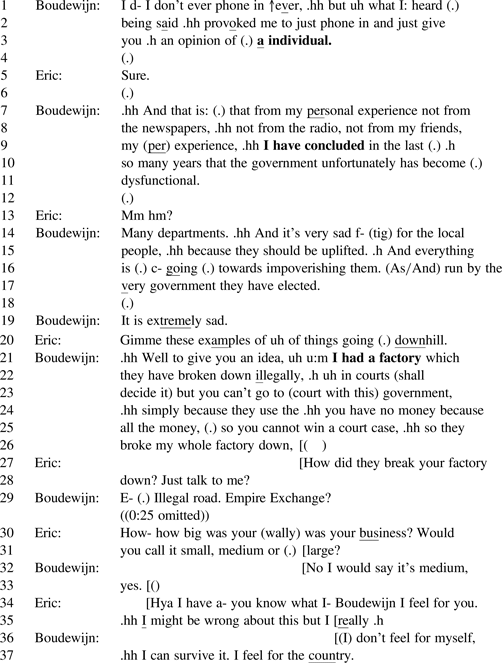

We can see forestalling operating again in extract (3), although here race is not the relevant MCD. In this case, Boudewijn has called in to comment on an exchange between the host, Eric, and a previous caller. In that previous exchange, Eric had criticized the South African government's failure to support small and medium-sized businesses, and the previous caller had then supported that position. In prefacing his response to that exchange, Boudewijn (who has just been identified by Eric as a first-time caller) claims to have been “provoked… to just phone in” despite having never done so before (lines 1 and 2). This formulation poses a puzzle as to what Boudewijn may have found so provocative about the preceding discussion to have prompted this (reportedly) unprecedented action on his part—and therefore what might have accounted for it (cf. Whitehead Reference Whitehead2009; Raymond Reference Raymond2019a). As he continues speaking, Boudewijn appears to be heading toward a self-identification (projected by the formulation “the opinion of” in line 3), but just as he reaches the crucial point at which a self-identification is due, he hesitates briefly, before claiming to be speaking as “a individual” (line 3). This slight hesitation, along with the marked use of the indefinite article “a” (rather than “an”) underlines the ‘non-categoricality’ of the self-descriptive “individual”. He then further sharpens the purely personal character of his yet-to-be-articulated pending response (lines 7–9). Thus, when he finally launches his response with “I have concluded” (line 9), the simple self-reference (and the opinion that follows on from it) have been carefully protected against categorical inference—at least, for now.

(3) [176, SAfm 4-28-08]

Nevertheless, Boudewijn is eventually pressed to reveal his germane membership category (albeit rather obliquely) under questioning by Eric, noting that he “had a factory” (line 21; also see lines 30–33), before going on to complain that the government had illegally demolished it (lines 22–26). In mentioning his membership in the business-owner category, he finally reveals that he has a stake in the discussion at hand. As such, his alignment with Eric's criticisms of the government is revealed as somewhat self-serving,Footnote 5 and thereby vulnerable to being discounted on the basis of this now-revealed category membership.Footnote 6

In constructing a ‘just-speaking-as-an-individual’ claim (as in extracts (1)–(3)) speakers are oriented to—and are, at the same time, resisting—the possibility that, in the absence of an explicit assertion to the contrary, recipients may well infer their membership in a particular—topically infelicitous—category. Moreover, as shown in the next extract, speakers do have at their disposal a rather straightforward technique aimed at pushing back against such implications—one that is expressly designed to ‘de-categorize’ a simple self-reference in the course of its production, and to do so without disrupting the progressive development of their ongoing turn-at-talk: Speakers can ‘personalize’ a simple self-reference by simply appending the term ‘personally’ to it.

In extract (4), taken from the same call as extract (2), David personalizes his simple self-reference, thereby discounting a possible racialized—and hence racist—source for his displayed skepticism toward Barack Obama's candidacy.

(4) [602, 702 5-5-08]

David's questioning of race-based support for Obama potentially implicates a race-based account for the skepticism he displays in asking the question. That is, by effectively using race to account for support for Obama, David provides a warrant for recipients to then use a racial category to account for the position his question reveals—by attributing it to white racism on his part (see Whitehead Reference Whitehead2009 on ‘categorizing the categorizer’). This possibility is underscored when Keeno passes up the opportunity to respond during a 0.5-second interval (line 5), and David then issues a partial backdown (line 6). This backdown exhibits his orientation to Keeno's withheld response as indicative of incipient disapproval of David's racialized challenge (cf. Pomerantz Reference Pomerantz, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage1984; Whitehead Reference Whitehead2015). Following another brief interval (at line 7), Keeno issues just a minimal acknowledgment (line 8) of David's question (cf. Gardner Reference Gardner1997). In response to this, David personalizes his simple self-references (at line 9 and again at line 11) as a way to de-racialize his viewpoint. In this way, he can frame his position on Obama as personal, rather than as tied to his membership in a racial category.Footnote 7

Having shown how speakers can forestall the categorical relevance of their self-presentations in general and their simple self-references in particular, we next examine how speakers manage recipients’ possible miscategorizations by adding category-based elaborations to their simple self-references.

When simple self-reference is treated as a source of possible recipient miscategorization

Lerner & Kitzinger (Reference Lerner and Kitzinger2007) have shown that speakers sometimes replace an individual self-reference (‘I’) with a collective self-reference (‘we’), thereby fine-tuning the self-reference for the action of a turn at talk. For instance, a speaker can convert individual responsibility for an action into the collective responsibility of a couple or into an organizational policy by replacing ‘I’ with ‘we’ (see Lerner & Kitzinger Reference Lerner and Kitzinger2007:546–48). Further, Lerner and colleagues (Reference Lerner, Bolden;, Hepburn and Mandelbaum2012) describe how ‘reference recalibration repairs’—including replacing non-categorical references to persons with membership-categorical references—can contribute ‘what is known about a category’ to sharpen the action of a turn.Footnote 8 In addition, conversation analytic research has shown that speakers not only initiate repair on misunderstandings displayed in prior turns-at-talk (e.g. Heritage Reference Heritage1984; Schegloff Reference Schegloff1992b), but also work to manage possible and even potential misunderstandings (e.g. Maynard Reference Maynard, Hayashi, Raymond and Sidnell2013; Raymond Reference Raymond2019b).

In this section, we consider situations in which speakers appear to target and manage possible or potential recipient misattribution of category-relevance to their simple self-references. Here, we describe circumstances in which the relevance of membership self-categorization can be found in the management of troubles that can arise from simple self-references that are initially left standing, with their possible category relevance at first remaining tacit—perhaps left to be gleaned by recipients from the thick particulars of content and context. We consider two sources of trouble associated with simple self-reference that are then targeted for elaboration via explicit self-categorization. In the first case, a speaker elaborates a simple self-reference when an evidently category-bound action is not acknowledged as such by a recipient; and in the second case, a speaker elaborates a simple self-reference when a recipient might well be (mis)led to infer the wrong membership category from the feasibly category-bound position the speaker has taken.

When an implied category is not acknowledged by a recipient

In extract (5), the caller (Andrew) tells of being denied the use of a bathroom at an embassy he was visiting (lines 5–18). In the South African context, this type of story can readily (although not invariably) be understood as implementing a complaint about racial discrimination—that is, it can be understood as a category-bound action ascription—with such an understanding providing a solution to the apparent puzzle of why an embassy employee may have refused to allow Andrew to use a bathroom (cf. Whitehead Reference Whitehead2009).

However, during an extended exchange in response to this story (lines 19–25, and in the omitted portion of the call thereafter), the host, Keeno, does not consider Andrew's membership in any category as relevant for uptake of his story. That is, although he displays sympathy for the difficulty arising from not having a bathroom available when one is needed, he treats the story as an at-face-value account of the embassy not having a bathroom—and in doing so, effectively treats Andrew as an individual, and thus Andrew's self-references in telling the story (especially in lines 12–14) as not category-implicative.

(5) [535, 702 4-23-08]

Subsequently, Andrew then explicitly categorizes himself (the protagonist in the story) as “Black African” (line 28), in contrast to his antagonist (“a white man” at line 31). Moreover, Andrew then reiterates this contrast by noting that he is “talking from a… Black point of view” (lines 42–43) and that he was “talking to… a white person” (lines 46–47). These categorical contrasts make explicit the upshot of the story: accusing the embassy employee of racial discrimination. In doing so, they retrospectively expose and deal with a categorization trouble source arising from Andrew's self-references earlier in the call (particularly those on lines 12–14) being evidently designed as tacitly racialized, but never acknowledged as such by his recipient.Footnote 9

When a recipient might have reasonably inferred a wrong category

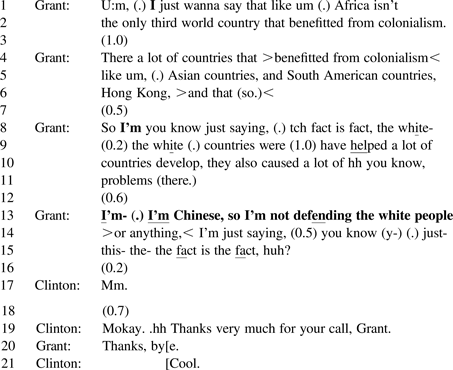

Extract (6) presents a case in which no membership category is mentioned in a self-reference, but the action formed up in the turn comes to be treated as mistakenly implying a categorical identity for its speaker. Prior to this call, there has been a discussion that involved a strong condemnation of colonialism, and a consensus that it was harmful to colonized countries. In contributing to this discussion, a caller, Grant, makes the counterclaim that many countries have benefitted from colonialism—so his claim goes against the anti-colonial consensus that has been established during the prior discussion.Footnote 10

(6) [549, 702 4-23-08]

Following the claim Grant makes (lines 1–2), and at several places thereafter where he pursues an aligning response (lines 4–6 and 8–11), Clinton (the host) does not respond. Grant then treats Clinton's non-responses as indicative of incipient disagreement (cf. extract (4) above), as he produces, post hoc, an explicitly categorized contrast between himself (as “Chinese”) and “white people” to manage what he treats as a possible miscategorization of himself by Clinton (lines 13–14). In producing this categorized contrast, Grant appears to orient to Clinton as having feasibly heard him to be speaking as a white person in defense of colonialism—a position that would be vulnerable to being discounted on the basis of the category membership of the speaker who has taken it (cf. extracts (1) and (2) above). By explicitly categorizing himself as Chinese, Grant establishes himself as a ‘cross-member’ (Sacks Reference Sacks1992:vol. I, 590)—that is, as a member of a different category from the same (race) MCD—and thereby heads off being heard as merely offering the viewpoint one could expect of a white person (cf. Whitehead Reference Whitehead2020). This self-categorization thus (retrospectively) contributes to the formulation of his prior claim as addressed to “the fact” (line 15), rather than as tied to a racialized ideological position (bound to the category ‘white people’).

Contrastive entanglement: A practice for tacitly categorizing simple self-reference

Our analysis thus far has focused on how speakers explicitly manage the category-relevance of their self-presentations. We now turn to situations in which membership categories are never mentioned, but where otherwise simple self-references are produced in a manner that conveys the speaker's membership in a particular category. In introducing the practice of contrastive entanglement through which this is accomplished, we are supplying one procedural specification for Land & Kitzinger's (Reference Land and Kitzinger2007:523, n. 19) observation that ‘It is sometimes possible for “I” (and its grammatical variants) to be heard, in context, as indexing a particular category of person’.Footnote 11

This practice entails a speaker employing a simple self-reference term such as ‘I’, but particularizing its delivery by adding contrastive stress (see Bolinger Reference Bolinger1961), thereby separating themselves from—while juxtaposing themselves to—another (discoverable) person or persons. This establishes a puzzle as to the basis upon which the speaker and other(s) are being contrastively entangled in forming up the action of the turn. Or posed differently, recipients are tasked with determining which MCD could partition these contrasted referents as ‘cross-members’ of a collection of membership categories.Footnote 12

Ogden & Walker (Reference Ogden, Walker, Szczepek-Reed and Raymond2013:307) have found that ‘high-level social actions like “offer” or “complaint” do not have phonetic properties of their own; but such actions and activities are implemented through more generic practices (to do with e.g. handling turn-taking, sequence, seeking alignment) which have phonetic exponents’. By contrast, Schegloff (Reference Schegloff1998:249) found that in specific, characterizable situations, ‘practices of prosody may contribute to a turn being analyzable as a “possible compliment”’. In particular, he describes how displacing the primary stress of a TCU by one beat and one word, ‘invokes a connection, a pairing, with something else’ (Schegloff Reference Schegloff1998:249). And, as Schegloff (Reference Schegloff1998:249) notes, ‘In providing for a “connection” between some unit in which the stress occurs… and some other such unit… this practice invites inclusion in what Sacks referred to as “tying techniques” (Reference Sacks1992:vol. I, 150–55, 716–23, 30–37, et passim)’.

The use of a stressed simple self-reference as a tying technique can be seen in Extract 7.Footnote 13 Here, the contrastively stressed self-reference term (‘I’) is accompanied by a correspondingly stressed recipient reference term (‘you’) that overtly targets just which other person the speaker is thereby juxtaposing himself to—but without making the basis of that entanglement explicit. In this case, the caller, Wayne, offers a negative assessment of a controversial twelve-meter-long walk-in sculpture of a vagina, describing it as “a little bit absurd” (line 9), and treats his membership in a sex category as relevant in doing so (lines 6–7). After receiving no response during the interval at line 10, which (as in extract (6)) may well adumbrate incipient disagreement, Wayne solicits alignment from the host, Aubrey, via his assessment of the sculpture (line 11). It is apparently by reference to Aubrey's status as a co-member of the category Wayne has just invoked—as a fellow male—that he is soliciting Aubrey's alignment with his assessment. However, instead of following Wayne's lead, Aubrey produces two contrastively stressed self-references (“I”, line 13), as well as a contrastively stressed recipient-reference to Wayne (“you”, line 14), that together appeal to his membership in the radio host category in contrast to Wayne's membership in the caller category.

(7) [691; 702 8-19-13]

This contrastive entanglement can lead recipients (including the overhearing audience) to work out what MCD can relevantly categorize him on the one hand, and Wayne on the other hand, so as to account for his deflecting response. Whereas, Wayne has introduced the sex MCD as a basis for categorizing himself, thereby also implicating Aubrey (see Whitehead Reference Whitehead2009), this MCD does not provide a solution for the puzzle of what contrastive identities would provide for Wayne, but not Aubrey, properly offering an opinion on this matter, since Aubrey and Wayne are co-members of a category from the sex collection. Instead, the solution requires them to be cross-members. The readily available solution, then, is Aubrey's membership in the ‘host’ category, in contrast to Wayne's membership in the ‘caller’ category.Footnote 14 This bolsters his claim that his opinion “doesn't matter” (line 13) relative to that of Wayne by evoking the category-bound activities and expectations that hosts should facilitate the expression of opinions on the topic at hand, whereas callers should express their opinions. In response, Wayne accedes to Aubrey's deflection (“Okay”, line 15) and then goes on to produce a further assessment of the sculpture. In this case, the speaker's contrastive entanglement involves both a contrastively stressed self-reference and a contrastively stressed recipient reference. However, contrastive entanglement can be accomplished by employing only a contrastively stressed self-reference. This can be seen in the remaining cases. In extract (8), the speaker employs an unstressed recipient reference, whereas in extracts (9) and (10) the entangled ‘other’ remains entirely tacit.

Extract (8) is taken from a backyard gathering of three couples. Just before the extract begins, Mike has addressed a ‘dick measuring’ joke to Curt and Gary. This is apparently a genre that circulates principally amongst men (cf. Sacks Reference Sacks and Schenkein1978), and as such, its telling can make the sex MCD relevant. On its conclusion, Curt produces a story preface that launches a next joke-story on the same theme. However, the joke's actual telling is delayed because of resistance from his two principal recipients (Mike and Gary), as seen at the beginning of the extract (lines 1–13). Then, just as Curt's recipients reluctantly align as joke recipients (see especially line 14), Carney, who is seated with her back to the table, and thus facing away from the other participants, interjects, “You ferget I’m here” (line 19), with contrastive stress on the self-referential “I”.Footnote 15

(8) [Auto Discussion, 44-45]

As in extract (7), the contrastive stress Carney produces on her self-referential “I” makes it relevant for her recipients to work out just how she is separating herself from the others present. This contrastive entanglement presents recipients with a puzzle: What MCD can relevantly categorize Carney on the one hand, and the others present on the other hand, given the positioning of her interjection between two dick-measuring jokes. It is, of course, the sex MCD that furnishes the solution to this puzzle. Although palpably gendered joke-telling is ongoing, it is Carney who exposes this through contrastive entanglement. In response, the recipients show their understanding of the gendered (but non-serious) point of Carney's protest, as Curt accepts it with “Ulright” (line 20), and then both he and Carney simultaneously begin to laugh (lines 21 and 22), with Mike joining in shortly thereafter (line 23).

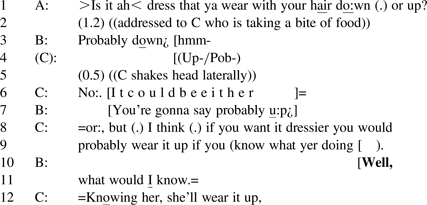

Land & Kitzinger (Reference Land and Kitzinger2007:523, n. 19) provide the following convergent analysis of another instance of tacitly gendered self-reference (here displayed as extract (9)):

…over a videotaped family meal [FAM38] at which mother and daughter are discussing a non-present person's proposed clothing and hairstyle for a forthcoming event (she'll be wearing “crinoline”, “very Cinderella”, “like a wedding dress”), the daughter asks whether this person's hair will be “down or up”. The mother's response is delayed (she is chewing) and the son volunteers “Probably down”. He is corrected by his mother who says that “if you want it dressier you would probably wear it up”—where the generic “you” treats her correction as being based in taken-for-granted knowledge about appropriate women's hairstyles for a “dressy” occasion. The son accepts correction saying, “Well what would I know”. Here “I” is at least open to being heard as indexing the category of “males” to which the speaker belongs—a category of persons supposedly ignorant about women's “dressy” hairstyles (and not included in the generic “you” his mother has used), thus accounting for his erroneous guess.

(9) [FAM38]

As in extracts (7) and (8) above, B's self-referential “I” here (line 11) is contrastively stressed, making it relevant for his recipients to work out just how he is separated from C in a way that would account for his relative ignorance of proper hairstyles. In this case, the sex MCD is implicated in and as the discussion of occasion-specific gendered hairstyle choices that is, in the first place, bound to the membership category ‘woman’. By focusing on the enabling technique underpinning Land and Kitzinger's observations on the possibly gendered nature of B's self-reference, our analysis elaborates their observations by grounding them in specific features of the talk. In this case, B's contrastively stressed self-reference points to his own membership in the other category from the same collection (‘man’)—and does so without mentioning either category. Here, B is employing contrastive entanglement to produce an account for his relative ignorance with respect to the types of hairstyles being discussed—thereby implementing his self-deprecating backdown from the opinion he had tentatively ventured.

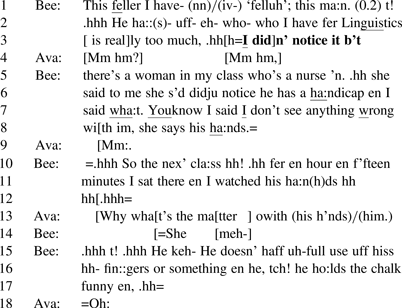

In extracts (7)–(9), contrastive entanglement ties the speaker to a recipient, whereas in extract (10), the speaker employs contrastive entanglement to tie herself to a non-present referent.Footnote 16 In this case, Bee recounts how a classmate pointed out to her that their instructor “has a handicap” (line 6), and employs contrastive entanglement to account for her own relative lack of ‘professional vision’ (Goodwin Reference Goodwin1994) compared to that of her classmate.

(10) [TG:6:1-42]

In contrast to extract (9), where a gendered basis for speaker ignorance allows the speaker to invoke membership in a sex category as an excuse, here ignorance is tied to the speaker's status as a layperson, vis-à-vis a professional. Bee adds contrastive stress to her self-references (“I” at lines 3 and 7) and then contrasts herself to a classmate she describes categorically as “a nurse” (line 5). Although a vocational category is employed, the relevant contrast here is between ‘layperson’ and ‘professional’. The relevant self-referential category (layperson) invoked via this contrastive entanglement remains tacit (as in excerpts (7)–(9)), but nevertheless accounts for how Bee's classmate could notice something ‘wrong with his hands’ (lines 7 and 8), while Bee was only able to see that “he has a handicap” once it was pointed out to her—by a professional.

Concluding remarks

Our investigation demonstrates that, in addition to practices through which speakers explicitly promote a categorical understanding of a self-reference, speakers can employ practices designed to forestall such an understanding—albeit exposing a membership category as feasibly relevant in the process (extracts (1)–(4)). We have also shown that speakers may orient to—and can manage via self-categorization (extracts (5) and (6))—the possibility that a simple self-reference may have allowed or contributed to a skewed understanding of the position they are staking out.

These findings demonstrate that, despite the ordinarily opaque character of simple self-reference with respect to category membership(s), speakers can employ practices to manage (possible and actual) attributions of membership in one or more categories—and thereby attend to recipients’ grasp of their self-presentation in terms of its category-relevance (cf. Lerner et al. Reference Lerner, Bolden;, Hepburn and Mandelbaum2012; Heritage Reference Heritage2013). This serves as a mechanism through which the commonsense cultural knowledge associated with membership categories is reproduced time and again as a by-product of the everyday activities in which speakers find themselves engaged (also see e.g. Sacks Reference Sacks1992; Kitzinger Reference Kitzinger2005a; Whitehead Reference Whitehead2012; Raymond Reference Raymond2019b).

In contrast to practices that manage category membership explicitly, contrastive entanglement is employed to accomplish tacit categorization of an otherwise simple self-reference. It does so by tying speaker and another referent together in a discoverable fashion (as in extracts (7)–(10)). The local particulars of context and content, brought to bear under the auspices of contrastive entanglement, constitute a resource for producing tacitly categorized self-references that rely on (and thereby reproduce) recipients’ shared cultural knowledge of membership categories. As a result, the category-relevance of self-references may, on some occasions, be exploited by participants even in the absence of any explicit mention of a membership category. The common-sense knowledge associated with categories, along with speakers’ orientations to the accountability associated with membership in a particular category, can thus, on such occasions, be brought to bear without being named as such.

Finally, these findings refine our understanding of Goffman's concept of self-presentation in two ways. First, by formulating the ‘presentation of self’ in terms of practices for self-reference and its elaboration, we tie members’ self-presentation work to the machinery of talk-in-interaction. And second, by situating our analysis in turns at talk, we are able to specify just how and just where the presentation of self contributes to the definition of the situation: It does so by playing a part in the configuration of practical action.