Signficant outcomes

-

∙ The behavioural results indicate the involvement of the nitric oxide (NO) signalling system in the antidepressant-like action of ketamine;

-

∙ The molecular data reveals ketamine-induced changes in NO signalling in the frontal cortex and hippocampus, and indicates that increased cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels may be important for the antidepressant action of ketamine.

Limitations

-

∙ The behavioural test used in this study is not appropriate for the evaluation of onset of action of antidepressants, and the results can therefore not reveal whether NO signalling is specifically involved in the time of onset of ketamine’s antidepressant effect.

-

∙ The observation that l-arginine on its own did not increase, but instead decreased constitutive NOS (cNOS) activity in both brain regions tested, complicates the interpretation of the results.

Introduction

A relatively recent and potentially ground-breaking discovery in antidepressant research has been that a single intravenous administration of a sub-anaesthetic dose of ketamine, an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, elicits a rapid (within a couple of hours) improvement of mood in depressed patients (Reference Berman, Cappiello and Anand1–Reference McGirr, Berlim, Bond, Fleck, Yatham and Lam4). Preclinical studies have identified a number of molecular mechanisms that appear to underlie the unique antidepressant profile of ketamine (reviewed in (Reference Duman, Li, Liu, Duric and Aghajanian5)). Briefly, it is thought that by increasing glutamate signalling through α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors relative to NMDA receptors (Reference Maeng, Zarate and Du6), ketamine activates a cascade of downstream cellular processes, including protein kinase B (Akt), extracellular signal regulated protein kinase (ERK) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), hereby leading to a rapid increase in synaptic protein synthesis and synaptogenesis in the frontal cortex (Reference Li, Lee and Liu7).

However, although our understanding of these downstream pathways are ever expanding, the specific signalling mechanisms that are affected further upstream, that is, directly downstream of NMDA receptors following their antagonism by ketamine, remain largely unexplored. A possible mechanism may involve the glutamate (Glu)/N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)/NO/cGMP signalling pathway: neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), the major NO producing enzyme in the brain, is physically coupled to NMDA receptors via postsynaptic density protein 96, and increases NO production in response to the Ca2+ influx produced by glutamate-mediated NMDA receptor activation (Reference Christopherson, Hillier, Lim and Bredt8). Released NO stimulates soluble guanylyl cyclase, which leads to the synthesis of the second messenger, cGMP.

There are several indications for the involvement of the Glu/NMDAR/NO/cGMP pathway in the pathophysiology of depression as well as in the action of antidepressants. For example, depressed patients exhibit elevated plasma nitrate levels (Reference Suzuki, Yagi, Nakaki, Kanba and Asai9), whereas pre-clinical studies have demonstrated antidepressant-like effects following the local or systemic administration of NOS inhibitors (Reference Heiberg, Wegener and Rosenberg10–Reference Montezuma, Biojone, Lisboa, Cunha, Guimaraes and Joca16). Furthermore, the Glu/NMDAR/NO/cGMP pathway has been shown to be involved in the antidepressant-like activity of a range of different drugs using rodent models (Reference Wegener, Volke, Harvey and Rosenberg11–Reference Harkin, Bruce, Craft and Paul13,Reference Jesse, Bortolatto, Savegnago, Rocha and Nogueira17–Reference Krass, Wegener, Vasar and Volke22). The specific brain area(s) that are involved in these effects remain unclear, but it appears that the hippocampus may play an important role. For instance, the intra-hippocampal injection of an NMDA receptor antagonist (Reference Padovan and Guimaraes23) or a selective nNOS inhibitor (Reference Hiroaki-Sato, Sales, Biojone and Joca14,Reference Joca and Guimaraes24) produces antidepressant-like effects, whereas local administration of serotonergic antidepressants reduces hippocampal NOS activity in rats (Reference Wegener, Volke, Harvey and Rosenberg11).

A recent study has provided the first evidence suggesting that the glutamate/NMDAR/NO/cGMP pathway may be involved in the antidepressant action of ketamine (Reference Zhang, Wang and Shi20). This study found that pre-treatment of healthy Wistar rats with the NO precursor, l-arginine, prevented the antidepressant-like effect of ketamine in the forced swim test (FST), and in the same study it was shown that ketamine decreased NOS activity in the hippocampus. Here we further investigated the involvement of NO signalling in the antidepressant action of ketamine by using a well-validated genetic rat model of depression, namely the Flinders sensitive line (FSL) rats (reviewed in (Reference Overstreet, Friedman, Mathe and Yadid25,Reference Overstreet and Wegener26)). Specifically, we tested whether pre-treatment with l-arginine (30 min before ketamine) can prevent the antidepressant-like effect of ketamine in this model of depression, while evaluating changes in total NOS activity [referred to here as constitutional NOS (cNOS) activity] and cGMP levels in the hippocampus and frontal cortex, as a measure of the activation state of the Glu/NMDAR/NO/cGMP pathway in these regions.

Methods

Animals

Male FSL and Flinders resistant line (FRL), weighing 274.4±7.7 g, were used. Animals were pair-housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 06:00 a.m.), with ad libitum access to food and water. All animal procedures were carried out under the approval of the Danish National Committee for Ethics in Animal Experimentation (2012-15-2934-00254).

Treatments

Thirty-two FSL rats (eight rats per group) were randomly assigned to the following treatment groups: (1) vehicle (saline), (2) ketamine (15 mg/kg, i.p.), (3) l-arginine (500 mg/kg, i.p.) and (4) l-arginine+ketamine. One group of FRL rats (n=8) were included to validate the depression-like phenotype of FSL rats, and to investigate baseline differences in NO signalling between the two strains. The l-arginine injections were given 30 min before ketamine, which was administered 1 h before the FST. FSL rats that did not receive either l-arginine or ketamine at a specific time point, as well as all FRL rats, received vehicle injections (saline, i.p.) at these times. The drug doses were based on previous reports using these drugs in rodents (Reference Li, Lee and Liu7,Reference Heiberg, Wegener and Rosenberg10,Reference Jesse, Bortolatto, Savegnago, Rocha and Nogueira17,Reference Krass, Wegener, Vasar and Volke22,Reference Garcia, Comim and Valvassori27). Animals were decapitated 90 min after ketamine or vehicle injection, and the frontal cortex and hippocampus regions dissected and kept at −80°C for subsequent molecular assays.

Behavioural testing

Open field test

Locomotor activity was assessed individually for each rat in a square open field arena (1 m2) for 5 min directly before the FST, in order to detect possible stimulatory effects of the treatments on locomotor activity, which may induce false positives in the FST. The behaviour of the animals was recorded digitally and the total distance moved (cm) was scored using EthoVision XT video tracking software (version 6.0.324; Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, The Netherlands).

FST

The FST was carried out as previously described (Reference Cryan, Markou and Lucki28). Briefly, the rats underwent a pre-swim session 24 h before the final test session by placing them into cylinders containing 30 cm of clean tap water at 22°C, for 15 min. This was done to induce a state of behavioural despair (Reference Cryan, Markou and Lucki28). Twenty-four hours later, the rats were again placed in the water-filled cylinders and subjected to another 5 min swim session during which their behaviour was recorded digitally. The time spent immobile, defined as when a rat makes only the necessary movements to keep its head above the water, was scored by an observer that was blind to the strain and treatment conditions.

cGMP measurement

Hippocampal and frontal cortical cGMP tissue levels were measured using a commercially available low-pH enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) kit (Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA), and by using the acetylated protocol for increased sensitivity. Measurements were corrected for protein concentration by using the BCA Protein Reagent Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

cNOS activity assay

Hippocampal and frontal cortical cNOS activity was assessed by measuring the rate of conversion of [3H] l-arginine (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) to [3H] l-citrulline, and was carried out using a commercially available kit (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The protocol was carried out according to manufacturer instructions. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Protein was determined using the BCA Protein Reagent Kit, and cNOS activity was expressed as pmol of l-citrulline produced per min per mg of protein.

Data analysis and statistics

Differences in between control FSL and FRL rats were analysed for each measurement by using Student’s t-tests (GraphPad Prism version 5.00; San Diego CA, USA). Treatment effects in FSL rats were analysed by using one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Newman–Keuls test. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Group sizes consisted of eight rats per group for all measurements.

Results

Behavioural tests

FST

Vehicle-treated FSL rats displayed an increased immobility in the FST compared with FRL controls (p<0.0001, Fig. 1a), thus validating the depression-like phenotype of FSL rats. Ketamine significantly decreased immobility in FSL rats [F(3,27)=3.96; p=0.014]. The ketamine-induced reduction in immobility was prevented by pre-treatment with l-arginine. Administration of l-arginine on its own did not affect immobility in the FST.

Fig. 1 Behavioural results obtained from the (a) forced swim test (FST) and (b) open field test in vehicle-treated Flinders resistant line (FRL) and Flinders sensitive line (FSL) rats, and FSL rats treated with ketamine, l-arginine or ketamine+l-arginine. Results are expressed as the mean±SEM. ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001 (Student’s t-test); *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (one-way ANOVA, Newman–Keuls test).

Open field test

FSL rats displayed significantly higher locomotor activity compared with FRL controls (p=0.0033, Fig. 1b). None of the treatments significantly altered locomotor activity in FSL rats [F(3,28)=0.864, p=0.47].

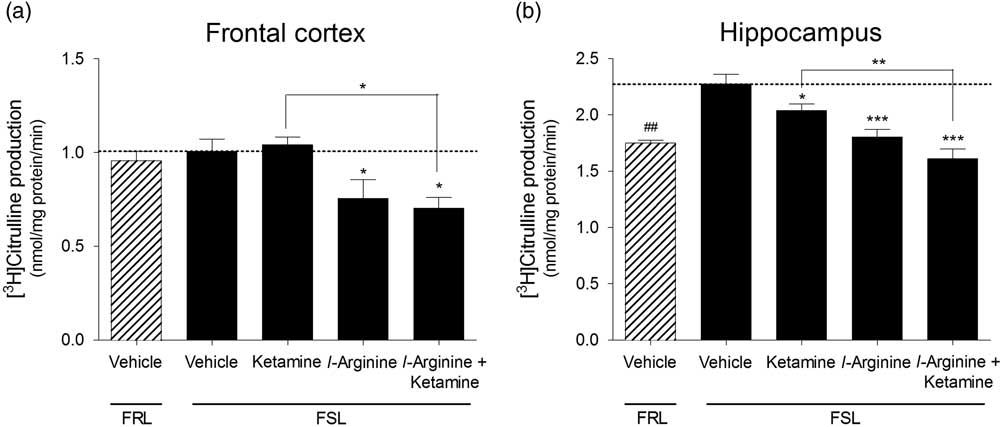

cNOS activity

Ketamine did not affect cNOS activity in FSL rats in the frontal cortex [F(3,26)=5.89, p=0.0033], whereas in the hippocampus, ketamine induced a small but significant reduction in cNOS activity [F(Reference Fond, Loundou and Rabu3,Reference Cryan, Markou and Lucki28)=14.61, p<0.001]. l-arginine treatment on its own reduced cNOS activity in the frontal cortex as well as in the hippocampus regions of FSL rats, whereas rats that received both l-arginine and ketamine exhibited reduced cNOS activities in both frontal cortex and hippocampus. We did not observe a significant difference in baseline cNOS activity in the frontal cortex of FSL rats compared with FRL controls (p=0.54, Fig. 2a). However, FRL control rats exhibited lower cNOS activity in the hippocampus compared with vehicle-treated FSL rats (p<0.001, Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2 Constitutive NOS activity measured in the (a) frontal cortex and (b) hippocampus of vehicle-treated Flinders resistant line (FRL) and Flinders sensitive line (FSL) rats, and FSL rats treated with ketamine, l-arginine or ketamine+l-arginine. Results are expressed as the mean±SEM. ##p<0.01 (Student’s t-test); *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (one-way ANOVA, Newman–Keuls test).

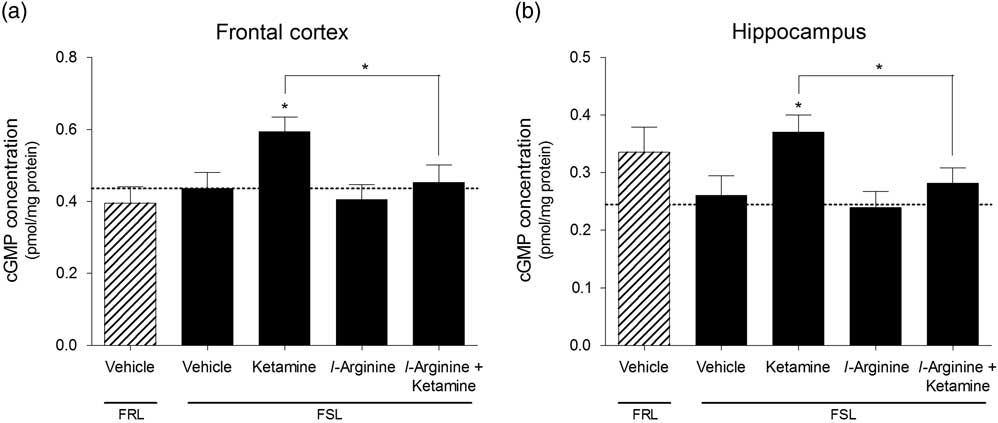

cGMP concentration

Ketamine induced a significant increase in cGMP concentration in the frontal cortex [F(3,26)=3.55, p=0.028] as well as hippocampus [F(3,28)=3.74, p=0.022] of FSL rats. This effect was abolished in both regions when rats were pre-treated with l-arginine. l-arginine on its own did not affect cGMP concentration either region. There were no significant baseline differences in cGMP concentrations in the frontal cortex (p=0.53, Fig. 3a) or hippocampus (p=0.20, Fig. 2b) of FSL and FRL rats.

Fig. 3 Cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) concentrations measured in the (a) frontal cortex and (b) hippocampus of vehicle-treated Flinders resistant line (FRL) and Flinders sensitive line (FSL) rats, and FSL rats treated with ketamine, l-arginine or ketamine+l-arginine. Results are expressed as the mean±SEM. *p<0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Newman–Keuls test).

Discussion

This study provides behavioural and molecular evidences to suggest the involvement of the Glu/NMDAR/NO/cGMP pathway in the antidepressant action of the NMDA receptor antagonist, ketamine. Together with a previous study (Reference Zhang, Wang and Shi20), these are the first direct evidences for such an involvement, although it could have been predicted considering the well-known physiological link between NMDA receptors and NO signalling. In accordance with the study by Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Wang and Shi20), we found that a systemic injection of the NO precursor, l-arginine, prevented the behavioural antidepressant-like action of ketamine in the FST (Fig. 1a), only here in a disease model of depression. This is a particularly interesting finding, since it points to an involvement of the Glu/NMDAR/NO/cGMP pathway in the antidepressant activity of ketamine. The depression-like phenotype of FSL rats was confirmed in this experiment by exhibiting a significantly higher immobility relative to control FRL rats. We did not detect any differences in locomotor activity induced by the treatments, and any changes in immobility can therefore not be attributed to alterations in locomotion.

On the molecular level, we found that ketamine induced a modest but significant reduction in cNOS activity in the hippocampus, but not in the frontal cortex (Fig. 2). This is in line with the evidences mentioned in the Introduction section that suggest that the hippocampus is an important site of involvement for the mood-altering function of the Glu/NMDAR/NO/cGMP pathway. Also, the study by Zhang et al. found a reduction in total NOS activity in the hippocampus following treatment with ketamine (Reference Zhang, Wang and Shi20), although this was the only region investigated. Interestingly, and seemingly in contrast to its inhibiting action on NOS activity, ketamine strongly increased cGMP levels in the frontal cortex as well as the hippocampus. Although l-arginine administration prevented the effects of ketamine in the FST and on cGMP concentration, its action on cNOS activity was somewhat unexpected in that l-arginine reduced cNOS activity in both brain areas. This result may, however, be explained by the metabolic conversion of l-arginine to agmatine, a molecule that is known to inhibit NOS activity (Reference Demady, Jianmongkol, Vuletich, Bender and Osawa29). This said, another study using the same dose of l-arginine reported an increase in NO end-products, although this study was carried out in mice (Reference Krass, Wegener, Vasar and Volke22). Another possible explanation may be that elevated arginine levels in the brain samples may have competed and interfered with the radioactive arginine used in the NOS assay. The data from our study can therefore not provide direct evidence that l-arginine blocks ketamine’s effects specifically by reversing its inhibiting action on NOS activity. Nevertheless, the reversal of the ketamine-induced elevation in cGMP levels in both brain regions by the co-administration of l-arginine (Fig. 3) does indicate that NO signalling is involved to some extent in ketamine’s antidepressant mechanism.

Considering that ketamine reduced cNOS activity in this study, a concurrent increase in cGMP levels may seem contradictory. However, this result may be explained by considering the intra- and extrasynaptic compartmentalisation of NMDA receptors. Ketamine is an open-channel NMDA receptor blocker, and is therefore theoretically more selective for extrasynaptic NMDA receptors, since these spend longer in the ‘open’ configuration because of a more tonic activation by extrasynaptic glutamate. Extrasynaptic NMDA receptors are known to induce long-term depression and are linked to neuronal inefficiency mechanisms (Reference Parsons and Raymond30–Reference Yashiro and Philpot32), and their selective antagonism can be expected to increase neuronal activity. Indeed, it has been shown that systemically injected ketamine induces an acute (within 20 min) increase in extracellular glutamate levels in the frontal cortex of rats (Reference Moghaddam, Adams, Verma and Daly33), which may be an indication of increased glutamate overflow from synapses due to enhanced neuronal firing. Thus, it may be postulated that the ketamine-induced increase in cGMP levels observed here may have resulted from an increased stimulation of intrasynaptically located NMDA receptors, secondary to enhanced neuronal firing caused by the blockade of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors on glutamatergic neurons. Another plausible explanation is that ketamine may block NMDA receptors on GABA-ergic neurons, leading to decreased GABA outflow and increased glutamatergic firing. In line with this, the involvement of GABA in ketamine’s antidepressant action has been demonstrated in a recent rat study (Reference Perrine, Ghoddoussi, Michaels, Sheikh, McKelvey and Galloway34).

The observation that l-arginine pre-treatment prevented both the increases in cGMP levels as well as the behavioural antidepressant-like effect of ketamine is strongly indicative of the involvement of elevated cGMP levels in ketamine’s antidepressant action. However, whether this underlies the rapid antidepressant action of ketamine remains to be shown, since the behavioural test used in this study (the FST) is not suited for evaluating onset of action. Other, more ‘chronic’ models of depression, such as chronic mild stress or olfactory bulbectomy may be considered for the future investigation of this hypothesis.

Lastly, we observed reduced cNOS activity in the hippocampus of FRL control rats relative to vehicle-treated FSL rats (Fig. 2b). This result is not all that surprising since a previous report has shown hyperactive NO signalling in the hippocampus of FSL versus FRL rats (Reference Wegener, Harvey and Bonefeld35), and is in agreement with other preclinical studies linking changes in NO signalling in the hippocampus to antidepressant action and depression-like behaviour (Reference Hiroaki-Sato, Sales, Biojone and Joca14,Reference Padovan and Guimaraes23,Reference Joca and Guimaraes24). This result can thus support the construct validity of FSL rats as a model of depression.

Conclussion

Together with another recent study (Reference Zhang, Wang and Shi20), we provide here the first behavioural and molecular evidences to indicate the involvement of the NO signalling pathway in the antidepressant mechanism of the rapid-acting antidepressant, ketamine. In particular, it appears that an increase in cGMP in the hippocampus and possibly the frontal cortex may play an integral role in its antidepressant mechanism. These findings contribute to our current knowledge regarding the link between the Glu/NMDAR/NO/cGMP pathway and the antidepressant mechanism of a rapid-acting antidepressant, and may assist future research in the ongoing search for novel faster-acting and more efficient antidepressants.

Acknowledgements

N.L. carried out planning and practical aspects of the study, as well as the majority of the manuscript preparation. G.W. and S.J. assisted with the interpretation of results and manuscript preparation.

Financial Support

The project was supported by the Danish Medical Research Council (grant 11-107897) and the AU-IDEAS initiative (eMOOD).

Conflicts of Interest

G.W. is Editor and S.J. Associate Editor in Acta Neuropsychiatrica. However, both G.W. and S.J. actively withdrew and were not involved in any decisions related to the present work. G.W. have received honorarium from H. Lundbeck A/S, AstraZeneca AB, Servier A/S, and Eli Lilly A/S.

Ethical Standards

All experiments were authorised, monitored and regulated by the Danish Committee on Ethics in Animal Experimentation (authorisation number: 2012-15-2934-00254).